Articles

Materiality, Affect, and the Archive:

The Possibility of Feminist Nostalgia in Contemporary Handkerchief Embroidery

Résumé

Cet article examine des travaux d’aiguille contemporains sur des mouchoirs anciens et identifie un nouveau genre féministe de travaux d’aiguille, en considérant la manière dont ces travaux révèlent la possibilité d’une nostalgie féministe. Ces travaux viennent compliquer la dichotomie entre l’approbation ou la désapprobation de la valeur des travaux d’aiguille historiques, qui toutes deux reposent sur une connexion essentialisée entre les travaux d’aiguille et la féminité normative. À l’examen des travaux de Leslee Nelson, Joetta Maue, Allison Manch et Ke-Sook Lee, j’avance que la matérialité et l’histoire du mouchoir en font un objet de médiation qui permet un engagement affectif et physique avec les archives non écrites des travaux et des sentiments des femmes. Le mouchoir procure aux brodeuses contemporaines un moyen d’explorer d’une nouvelle manière l’héritage féminin de la broderie, car il évoque, à travers l’histoire, des relations de souvenir, d’échanges, de communication codée, de sexualité, d’incarnation, et de régulation ou de contestation des normes de genre. À travers le médium qu’est le mouchoir et le processus de la broderie, ces artisanes abordent la féminité en tant que substance historique, comme quelque chose qui se répète dans la réalisation de la broderie et qui se sédimente dans les gestes et les objets matériels, comme des archives avec lesquelles elles peuvent être en relation et sur lesquelles elles peuvent intervenir.

Abstract

This paper examines contemporary needlework on vintage handkerchiefs, identifying a new genre of feminist needlework and considering the ways in which these works reveal the possibility of a feminist nostalgia. These works complicate the dichotomy between simple embrace or disavowal of the value of historical needlework, both of which rely on the essentialized connection between needlework and normative femininity. Looking to the work of Leslee Nelson, Joetta Maue, Allison Manch, and Ke-Sook Lee, I argue that the materiality and history of the handkerchief form render it a mediating object, one that enables an affective and physical engagement with an unwritten archive of women’s labours and sentiments. The handkerchief provides contemporary needleworkers with a way of exploring the feminine legacy of embroidery in new ways, as the handkerchief form evokes its historical relationships with remembrance, exchange, coded communication, sexuality, embodiment, and the regulation and subversion of gendered norms. Through the medium of the handkerchief and process of embroidery, these makers engage with femininity as a historical substance, something repeated in performance and sedimented in material objects and gestures, and as an archive they can intervene upon and find themselves in relationship with.

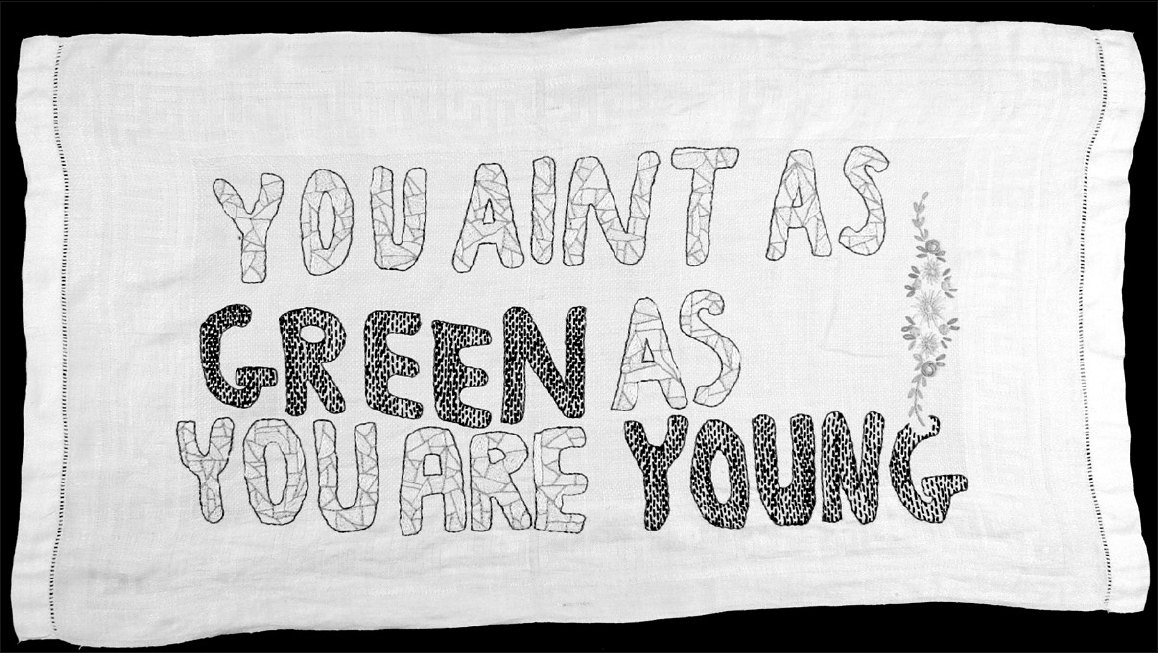

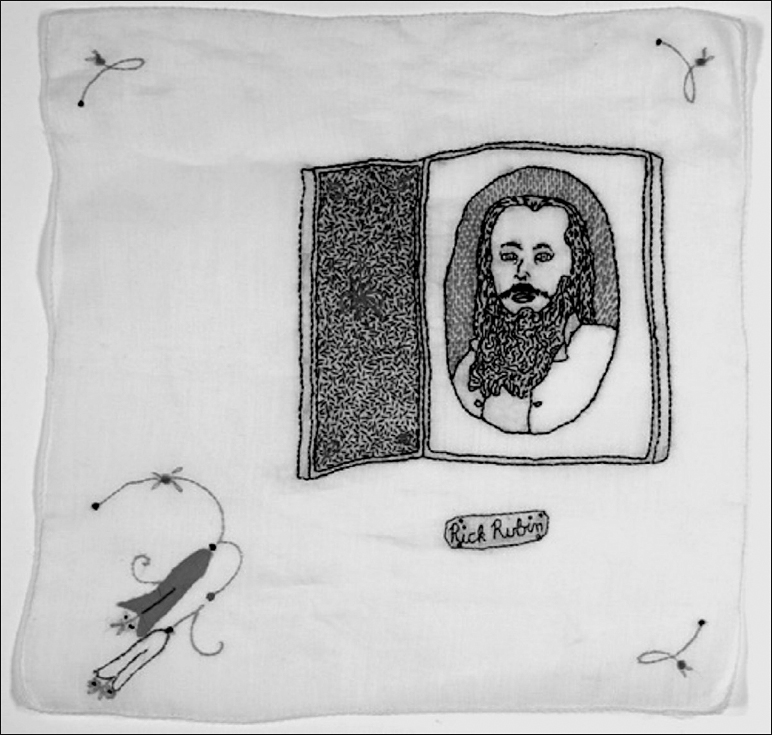

1 Allison Manch’s delicate yet uneven stitches pierce the surface of a faded, white linen marked with such signs of normative feminine beauty as a stitched floral bouquet. But it is the block letters that take the central place in the composition, spelling out lines from John Mellencamp’s “Hurts So Good”: “You aint [sic] as green as you are young” (Fig. 1). She sews into a vintage handkerchief, interrupting its translucent delicacy with heavy clusters of stitches that make up the features of Rick Rubin’s face. The co-founder of Def Jam is depicted as a near-religious icon, lovingly rendered (Fig. 2). There is humour in these pieces, a sense of jarring misalignment between content and medium. And, indeed, Allison Manch’s embroidery is typically cast as out of place, provocative, and grounded in the ethos of irony and revision that is ascribed to much contemporary stitching. It is this kind of juxtaposition that seems to drive contemporary, feminist, embroidered aesthetic. Manch stitches rap, pop, and rock song lyrics and icons on vintage linens (typically handkerchiefs), devoting immense time and care to the delicate, labourious stitching of pop cultural references that are considered disposable or trivial. Her work is often posed as a reworking of previous forms of embroidery, cast as indicative of a history of imposed, hegemonic codes of femininity that contrast with her playful, wry, and sometimes rude stitchings (Pela 2008).

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2

2 In choosing surprising content for her designs, Manch participates in a growing trend of subversive stitchers who perform liberated, feminist selfhood by highlighting a contrast with oppressions of the past, thereby suggesting fundamental difference from the meanings of historical embroidery. Where one might expect the moralistic, didactic verses of a schoolgirl sampler, artists like Manch instead stitch lyrics to J. Lo and My Bloody Valentine songs. However, I interpret Manch’s work as part of another emerging, but seemingly unidentified, trend of stitchers who open up new possibilities for a “feminist nostalgia” rather than irony—an affective and tactile relationship with a complicated past. I read these stitchers through their shared medium of the vintage handkerchief, and use its history to reframe the potential of contemporary embroidery, which can enable a material, affective engagement with an unwritten archive of women’s making.1

3 The contemporary landscape of hip, young feminist media is littered with references to the subversive status of modern textile craft, framing the recent resurgence of interest in traditional women’s work, such as embroidery, as an ironic reclamation of an imposed history or a revision of a staid and retrograde craft. “These Aren’t Your Grandma’s Cross-Stitch Samplers,” reads a 2014 headline from BUST, a mainstay of third-wave feminist pop culture writing (Bogert 2014). Time and again, contemporary textile work—particularly decorative needlework—is framed in opposition to a normatively feminine past, implicitly (and often explicitly) asserting the ways in which “good feminist” embroidery must engage in a kind of self-conscious revision. Countless Etsy accounts and pop culture feminist sites like BUST reify a shared assumption that conventional or historical ornamental embroidery is antithetical to feminism and in need of reclamation; they celebrate the ironic embrace of the feminine merged with the impolite, raunchy, or brash as a feminist intervention on normative codes of proper feminine performance. This works to establish a disconnection between contemporary feminist identity and historical feminine performance, limiting the possibility of felt, earnest connection with the past. And yet, that past remains, invoked with each new stitch. There are contemporary stitchers who occupy a space between embrace and disavowal, engaging with the felt meanings of needlework and entering into tactile relationships with a feminine material past.

4 This paper examines the developing practice of needlework on vintage handkerchiefs in order to complicate the apparent dichotomy between a simplistic embrace of an essentialized, feminine past and a self-proclaimed feminist disavowal of the value of historical embroidery. Looking to the work of Leslee Nelson, Joetta Maue, Allison Manch, and Ke-Sook Lee, I argue that the materiality and history of the vintage handkerchief renders it a mediating object, one that enables an affective engagement with and intervention on an unwritten archive of women’s labours, pleasures, and communication.2 Through the medium of the vintage handkerchief, these contemporary stitchers engage in the tangled, ambivalent work of a feminist nostalgia.

5 Their work does not celebrate the past, but seeks to engage with it and perhaps even to reshape it, to find felt connection with a seemingly inaccessible feminine archive. A sense of that inaccessibility comes through even in the flexibility of the categories of “handkerchief ” and “embroidery,” two terms that contemporary stitchers use to describe a wide array of historically contingent and shifting practices and objects. For the purposes of this paper, I am particularly interested in these stitchers’ embrace of handed down linens (generally handkerchiefs) and of decorative needlework associated with domestic femininity, rather than functional sewing or needlework performed for pay.3 By appropriating these methods and materials associated with a particular vision of domestic femininity understood to be indicative of the traditional, the conventional, the decorative, and craft rather than originality, usefulness, or the artistic, these stitchers all claim the use of needle and thread to make meaning. Through their stitching—their careful, piercing touches—they revalue the imposed and dismissed labours of women who came before them. Their works lay bare ambivalent relationships to femininity, memory, history, and the possibility of connection.

6 I explore the ways in which Nelson, Maue, Manch, and Lee engage with themes of tradition and ephemerality, pleasure and labour, intimacy and public exchange, and memory and illegible communications. Each of these pairs is held in tension in their work, demonstrating ways of connecting with a fraught medium, and exploring felt relationships between past and present, among disparate bodies, and with expectations about gendered performance. Each set of pairs also opens up a window into a different aspect of the history of the handkerchief, which, in turn, deepens an understanding of the work. Nelson’s “memory cloths” play on the ambiguous place of the handkerchief as a piece of ephemera, potentially disposable but also explicitly handed down and invested with sentimental meaning. Maue’s “reclaimed linens” directly engage with the handkerchief as a receptacle for bodily fluids, which both policed the boundaries of the self and demonstrated human porousness, infused with mess and sentiment. Manch’s “word portraits” and pop culture trivia open up a lens onto the history of the handkerchief as a token, an object that concretized affective relationships through exchange and display, materially demonstrating the relationally constituted self (O’Hara 2002: 63). Finally, Lee’s tantalizingly illegible “handkerchief hangings” call up the handkerchief’s history as a tool of coded flirtation and erotic signaling, playing with notions of unspeakability and the interplay of public and intimate. These works, then, do not constitute an essentialized feminine history, but are an acknowledgement of the residues that accrue to historical objects and the accretions of past gestures that are invoked in material performances.4 Rather than articulating a singular, clear position in relation to the past of embroidery and women’s gendered labour, these multivocal works enable a reading of embroidery’s potential to speak beyond the individual level, resonating with felt, unarticulated, collective meanings only accessible through touch and embodied performance. I argue that these specific works can open up a broader way of thinking about feminist nostalgia and the capacities of embroidery as a material practice with traditional meanings that seem impossible not to evoke and invoke in the act of stitching.

The Challenges of a Textile Inheritance: Needlework’s Gendered Past

7 Embroidery has a vexed and vexing relationship with articulations of gender performance, given its historical imposition on girls and women and its key role in constructing and displaying idealized visions of femininity.5 Scholars like Charlotte Gould (2013), Maureen Daly Goggin and Beth Fowkes Tobin (2009), Marla Miller (2006), Julia Bryan-Wilson (2017), Pamela Parmal (2012), Laurel Thatcher Ulrich (2001), and Rozsika Parker (2010), among many others, have clearly established the inextricable linkages between gender and embroidery (particularly decorative embroidery), noting that it is “not simply any kind of medium… but a gendered one, or more exactly, a supremely and paradigmatically gendered one” (Gould 2013: 5). In schoolgirl samplers intended to impart lessons about obedience and piety, needlework pictures meant to advertise marriageability, and the prioritization of girls’ sewing lessons to the exclusion of other forms of academic education, embroidery has long been a way to construct and enforce the boundaries of normative feminine identity performance. This speaks to both the domestic, ornamental needlework expected of white, educated, elite women and the ways in which training in needlework also operated as a troubling tool of “civilizing” women of other classes and races. However, though imposed upon generations of women in the service of both teaching and embodying appropriate modes of feminine identity performance, needlework can also be seen as a creative outlet for these same women, a medium of their own.6 Indeed, historians have illuminated some of the complex ways in which needlework both operated as a potential pathway to economic independence (or, at least, a form of self-support) and as a signifier of narrow visions of feminine, domestic existence.7 Contemporary needleworkers, at least since the 1970s, have openly struggled with ways of celebrating, critiquing, reclaiming, or simply using the medium. These histories live in materials.

8 It seems challenging for women to embroider without engaging with this history in more or less explicit ways; they are expected to explain, apologize for, or openly embrace their use of such a historically gendered medium. Particularly for self-identifying feminists, the reclamation of embroidery seems limited to the ironic, the self-pronounced subversive, grounded in a performance of critical distance or a claiming of the singularity of the artist’s vision. Lurking in the background seems to be the looming fear of an essentialized embrace of a feminine history, a cardinal sin in the third-wave feminist landscape, though an acknowledged strategy of many second-wave feminist art makers.

9 While much contemporary embroidery announces its difference from an imposed women’s history, it also seems to recoil from the more recent history of second-wave feminist interest in embroidery as “a medium with a heritage in women’s hands, and thus as more appropriate than male-associated paint for making feminist statements” (Parker 2010, xviii).8 Indeed, the performance of the historicity of embroidery is not simply an attribute of the most recent revival of interest in embroidery, but has been a mainstay of feminist art and craft practice at least since the 1970s. Artists like Judy Chicago, among others, made the relationship between embroidery and feminine history explicit, seeking to reconsider the historically denigrated practice and to embed themselves within it. Other second-wave feminists distanced themselves from the trappings of normative femininity, rejecting embroidery as a patriarchal tool used to impose visions of domestic, silent, decorative femininity (Parker 2010: xxi).

10 Each of these positions seems to operate in the realm of either a disavowal or an embrace of history, framing embroidery either as a medium in need of radical revision or ideally formulated for feminist articulations by virtue of its intimate relationship with both feminine traditions of making and its pedagogical role in articulating appropriate modes of embodying and performing femininity. Both positions seem to assert that embroidery was—and perhaps still is—essentially feminine and is therefore either a tool by which to reappraise that which has been historically denigrated or a dangerous practice that can only shore up oppressive notions of hegemonic femininity. This assertion posits a break between a self-aware, feminist present and a confined, embroidered past.9 However, the legacy of historically aware needlework stretches back much farther than these contemporary examples, demonstrating a longstanding understanding of embroidery as a tool through which to comment on and engage with the past. The medium itself seems intimately bound up with notions of tradition, inheritance, and history. Indeed, not only has embroidery created histories—embroidered works are themselves objects of inheritance—but it has long been used to express a relationship to its own history. Whether through the work of the Colonial Revival using embroidery to shore up connections with an imagined republican past, or in the self-consciously “traditional” patterns circulated in newspapers in the early 20th century that served to re-establish women’s connections to the home and history in urbanized, industrialized landscapes, stitching has long positioned women in relation to the past.10

11 Perhaps it is this intimate relationship to a sense of pastness that so complicates contemporary embroidery. Today’s popular feminist discourse seems to leave little room for articulations of nostalgia, an understandably challenging position to take within a discourse so grounded in critiques of historical structures and engaged with a progressive vision of the future. Of course, feminist discourse is also marked by refusals of narratives of teleology and the imperative to futurity. These positions, however, also tend to foreclose clear statements of nostalgia, of relating to an intelligible history. What, then, is one to do with the messy feelings that fall between condemnation of imposed practices that emerged under and reveal patriarchal structures and a wholehearted embrace of feminized material practices as evidence of an essentialized feminine connection?

12 Kate Eichhorn suggests that “notwithstanding its legitimate critiques … nostalgia may be more complex than once imagined…. Nostalgia may be a feeling that crosses many registers and, in this sense, does not signal a ‘reactionary desire for the past’ after all” (2015: 258). Instead, it might be an enabling affect, a way to engage with history, desire, and a sense of connection—or disconnection—a “temporal shift [that] opens up the radical politic that appears as committed to longing for both real and imagined versions of the past as it is to futurity and for one that is no longer premised on their opposition” (Eichhorn 2015: 253). Rather than constituting a longing for the past, contemporary feminist nostalgia—nostalgia with a critical lens—might enable ways to reconceive of the relationships between then and now. Acknowledging the limitations and silences of the archive and the inherent challenges with seeking inclusion in a history predicated on the exclusion of certain voices, bodies, and lives, feminist nostalgia can create space for an affective engagement with pasts, pleasures, and complex sentiments that evade clear articulation.

Leslee Nelson’s “Memory Cloths”: Tradition and Ephemera

13 On the surface, Leslee Nelson’s “memory cloths” are perhaps the most literal, legible examples of handkerchief embroidery as a site for felt connections with nostalgia. They are cast in terms of a feminine legacy, in ways resonant with certain second-wave feminist positions. The first statement on her institutional web page (she taught in the art department at the University of Wisconsin-Madison) firmly asserts, “I embroider my Mother’s and Grandmother’s handkerchiefs, and tea towels with my memories and thoughts” (Nelson 2012a). Nelson’s thirty-year career has investigated both personal memory and broader notions about a feminine history of serving as memory-keepers and memory-stitchers. Her work features handkerchiefs stitched with personal memories, messages, and lessons Nelson wishes to remember, and calls for viewer engagement.

14 A 2013 article advertising Nelson’s retrospective show in Madison described her work as featuring “[q]uilts that hug us. Napkins that dab our lips. Handkerchiefs that collect our tears,” working to draw the viewer into a shared relationship with Nelson’s materials and emphasizing bodily presence (Worland 2013). At this show, Nelson invited viewers to make their own memory cloths, casting the process as restorative, healing, and accessible to all, a “meditative process of embroidery [that] helps stitch together the past” (Worland 2013). In so doing, she also invoked the traditional social formation of the sewing circle, a site of communal making—sometimes literally disrupting any possible naming of a singular maker—and complex articulations of the relationship between femininity, domesticity, tradition, and public space. The sense of continuity and universality that frames the show and much of Nelson’s work is in tension with the immensely personal memories and messages that she often stitches. Nelson contextualizes each piece with a written description of the memory, implicitly stating that the intended meaning is only accessible for the stitcher through her textual mediation. The physical objects still hold something back, still resist articulation.

15 Some of her pieces are cast as interventions on her memories, ways to deal with the past in new ways. For example, “Valentine-Diamond” functions as a transformational object in her fraught relationship with her mother. Featuring a pink heart, and a densely stitched, silver diamond in its center, Nelson reveals that this handkerchief was, in fact, her mother’s wedding handkerchief, handed down to Nelson (Fig. 3). The accompanying text recontextualizes the seemingly innocuous, delicate piece, explaining that this was stitched just after her mother’s death. She thought of all the rage that she’d been holding towards her parents—the last words her mother said to her were “all I’ve taught you was anger”—and how she might burn that anger “into a diamond” (Nelson 2012b). She explains that “it was that anger that allowed me to refuse her suburban housewife role and find my own kind of life,” reimagining her negative inheritance as a gift (Nelson 2012b). By stitching into a literally inherited object, she also reshapes her memories, transforming her mother’s legacy. But this is not simple revision.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3

16 Nelson still engages with the physical and emotional remnants of her mother’s life and finds value in the domestic activity of stitching. Materially working with her mother’s wedding handkerchief, she makes it into a memento of multiple moments, no longer a simple signifier of her mother’s fulfillment of expected, feminine roles. In a way, Nelson accepts her mother’s inheritance and notes its value through the medium of the handkerchief and the technology of embroidery. Both position Nelson as the bearer of this feminine legacy and acknowledge a deep relationship to a history of other stitches and stitchers. In the moment of stitching, of holding the handkerchief, she is not alone. But she is also able to rework just what her specific relationship is to this historically feminized matter. The belated documentation of embroidery, of recording the memory rather than the event, is held up as a way to preserve a moment already experienced, to reconstitute it, or to rework its meaning.

17 These moments can often seem trivial, creating a personal archive of Nelson’s own memories that challenge notions of what counts as history. Nelson’s memory cloths work to mark moments that might otherwise slip through the cracks of both social and personal remembrance. Her archive is material and tangible, but also invokes the fleeting and the gestural. It engages with a literally handed down object and enters into a performative legacy through the personally and historically repeated act of stitching—a paradoxically immaterial and deeply tactile history. Embracing this sense of the performative, invocational nature of her work, Nelson sets the rule for herself that she cannot sketch out her design prior to the act of stitching. This speaks of the meditative state into which she enters, and how she positions herself as entering into relationship with the past through the act of stitching. It is almost as though she imagines channeling past moments through the needle’s pass through the handkerchief. As Diana Taylor writes, in the performative realm of the “repertoire”—the counterpart of the archive—“multiple forms of embodied acts are always present, though in a constant state of againness. They reconstitute themselves, transmitting communal memories, histories, and values from one group/generation to the next. Embodied and performed acts generate, record, and transmit knowledge” (2003: 21).

18 Karen McLaughlin’s short essay on Leslee Nelson’s memory cloths is included on Nelson’s University of Wisconsin web page, further bolstering a reading of Nelson’s cloths as challenges to and interventions on the archive of women’s history. She writes of the cloths themselves, hanging in the Chazen Museum of Art for Nelson’s retrospective:

19 The cloths are directly figured as ephemera both at the level of medium and content, but are radically inserted into the space of the monumental, the official, and dominant notions of the culturally significant. Read through José Esteban Muñoz’s work on ephemera, the handkerchief can be seen as the site of a radical revision of the archive. Although Muñoz grounds his work in the examination of the fleeting—looking to gossip, evanescent moments of connection, and the performative to think through the possibilities of a queer archive—he also emphasizes “following traces, glimmers, residues, and specks of things” that constitute “evidence of what has transpired but [are] certainly not the thing itself” (1996: 10).

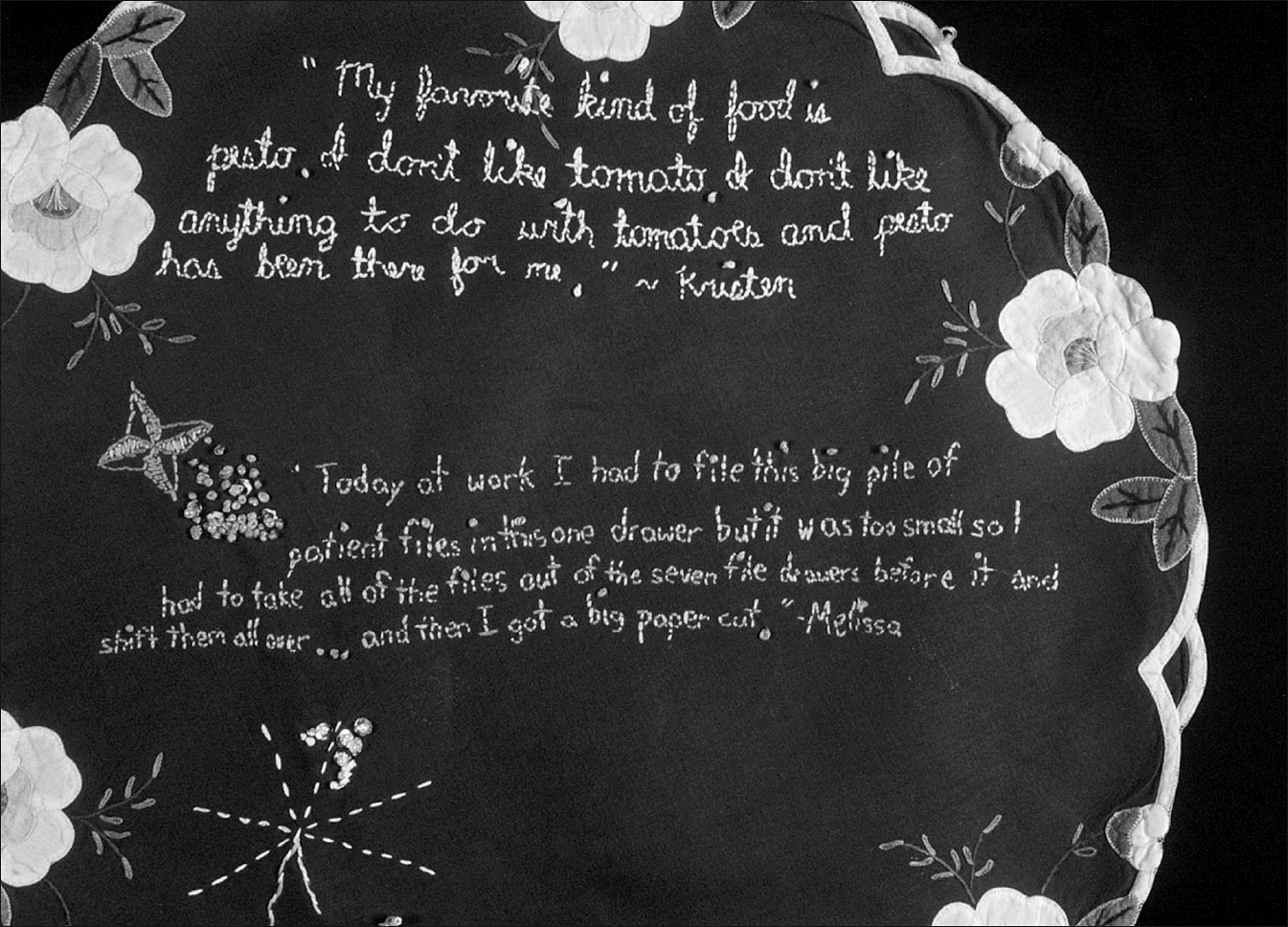

20 Muñoz argues for the uses of the anecdotal, the remembered, the ephemeral, and the performative for those for whom the archive is a blank, haphazard, or largely imposed narrative, or one that is unrecognizable. Similarly, Nelson’s works play with notions of presence and absence, the monumental and the disposable, and the felt connections to residue that might constitute an ever-incomplete, but also never closed, archive. Resisting clear assertions of rejection or embrace of complicated and often painful histories, these handkerchief works enable participation in affectively charged traces of feminine materiality, making, feeling, and being.

21 Although this challenge to temporality and, in many ways, to the singularity and boundedness of individual consciousness does seem to open up spaces for liberating narratives or, at least, affective refigurings of incomplete or imposed narratives, it is important to note the ways in which reconstituting history might also effect an erasure. Nelson’s work, in particular, illuminates some of the challenges of temporal and material play, as she notes that she first got the idea of specifically stitching “memory cloth” when she saw such items in an exhibit put on by women in South Africa to give voice to those narratives they felt had been left out of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Nelson says that she “wondered whether it was appropriate to use a technique that recorded the horrific violence of Apartheid to tell stories from my protected Midwestern, middle-class, middle child’s life. I realized that the center of the stories that inspired me lay in their belief in the power of deep discovery, forgiveness, and healing” (2008: 51).

22 Nelson enters into the realm of the universal here. Though her experiences might be different from “these women who have these incredible traumas (in their past)—people being murdered, their houses being burnt down,” she reads the process of accessing and reflecting on painful (and joyful or trivial) experiences through stitching on memory-infused cloth as a shared, mobile process (Worland 2013). Nelson’s work is deeply personal and specific and does insist upon the importance of particularity, of material histories as important counternarratives to the nebulous haze of an undifferentiated feminine past. But it is important to note what can happen when entering into the space of the gestural, affective, recursive, and ephemeral. A sense of ahistorical, global femininity can paradoxically accrue to these often deeply personal, nostalgic objects, and a form of levelling can take place. This paper does not seek to position these needleworkers in the realm of the moral, somehow valorizing this particular combination of technique and medium as essentially liberatory or as simplistically universal. Instead, I aim to identify an emerging practice and to consider its possibilities and, indeed, its challenges. The particularity of the histories and communities invoked through the stitch, in the touch of the handkerchief, are deeply important. My reading does not locate the performative or the communal as such capacious and permeable categories as to lose all sense of specificity. But it is worth noting the mobility of these forms and media that evoke their histories and makers, yet are flexible enough to be made ever anew. Maker, collaborator, viewer, and toucher can all access a well of overlapping, layered, and deeply personal meanings.

Joetta Maue’s “Reclaimed Linens”: Pleasure, Labour, and The Ambivalent Trace

23 While Nelson’s work brings up notions of the cloth infused with tears—made explicit in Gayle Worland’s article—these bodily traces are framed more as indexes of sentiments. Her work focuses on the memories infused in cloths, but the history of the handkerchief is one of literal infusion, functioning as a container not simply for feeling, but also for bodily fluids. Joetta Maue’s finely wrought works are almost uncomfortably intimate, and force a consideration of the presence of bodies and the impressions left by touch. Using “reclaimed linens,” Maue renders figures who might have touched these surfaces, both invoking her own embodied labour in the density of her stitches and the physical traces of other women’s bodies in these linens. Her work is not limited to embroidery on handkerchiefs, but also explores the possibilities of pillowcases, sheets, and doilies, marking stains and rumplings of fabric with her stitches.

24 Handkerchiefs have long been understood as textiles that both regulate and reveal the messy, permeability of those boundaries.11 Catching tears, phlegm, blood, sweat, and a variety of other forms of “matter out of place,” handkerchiefs function as the containers of impurities, enabling the user to perform propriety and bodily cleanliness.12 Although often associated with nobility and upper class identities—and, at certain points in history, intensely policed to ensure this association—the handkerchief also carried with it the implication of a mess to be sopped up.13 In the late 1800s, the practice of “show and blow” perhaps best exemplified the paradoxical relationship between cleanliness or propriety and filth or bodily disorder represented in the handkerchief. Helen Gustafson notes that in many parts of rural America, as part of the project of “civilizing” children’s bodies, children were required to show their teachers a clean handkerchief each day. In order to cope with the inherent challenges of this task, mothers would often supply their children with two handkerchiefs, one that would be used, washed repeatedly, and begin to show signs of wear, and a second that would be used exclusively to present a vision of cleanliness to the teacher (2002: 26).

25 This bodily history is particularly attached to the monitoring of women’s physical boundaries, argues Will Fisher. In the early modern period, English women were paradigmatically associated with handkerchiefs. The display of a pristine, delicately embroidered “hand-kercher” demonstrated women’s purity and wealth, but also implied fundamental “leaky” qualities, the porosity and danger of their embodied states (Fisher 2000: 203). This historical danger—that of the overflowing woman—is a source of connection and love for Joetta Maue. Her works revel in the marks of wear, taken as indications that a body engaged with this material. She lovingly stitches blood spatter and unidentifiable stains into her pieces and lets pre-existing emblems of use go uncleaned. Although her work often positions itself in terms of very normative visions of femininity, her use of materials creates space for an acknowledgement of ambivalence, complexity, mess, and overflow of emotions, bodily fluids, and temporalities.

26 Her works on handkerchiefs tend to feature text tinged with sadness, invoking the history of sampler-making in quiet and nuanced ways. She stitches lines that challenge and inhabit the conventions of normative femininity, explore the ambivalent space of living in a body marked as female, and think through the sampler form as a legacy. The sampler form was originally used as both a lesson in stitchery and a collection of ornamental and communicative stitches that young girls would learn in anticipation of their future, married lives in which they would be expected to mark their household linens (Ulrich 2001: 129). These stitches could be combined in particular ways to denote the owner’s possessions, which could then be passed down as inheritance for her daughter (Parmal 2012: 24). This practical lesson in the skills of marking ownership was also an exercise in learning and embodying appropriate modes of femininity, which was constructed as docile, ornamental, emulative, and material rather than intellectual. Traditional, imposed forms of textile craft could thus be used to create matrilineal lines of inheritance, enabling both the transmission of knowledge and tightly governed norms of feminine behaviour and the literal transmission of material goods in a socio-legal context that limited female ownership.

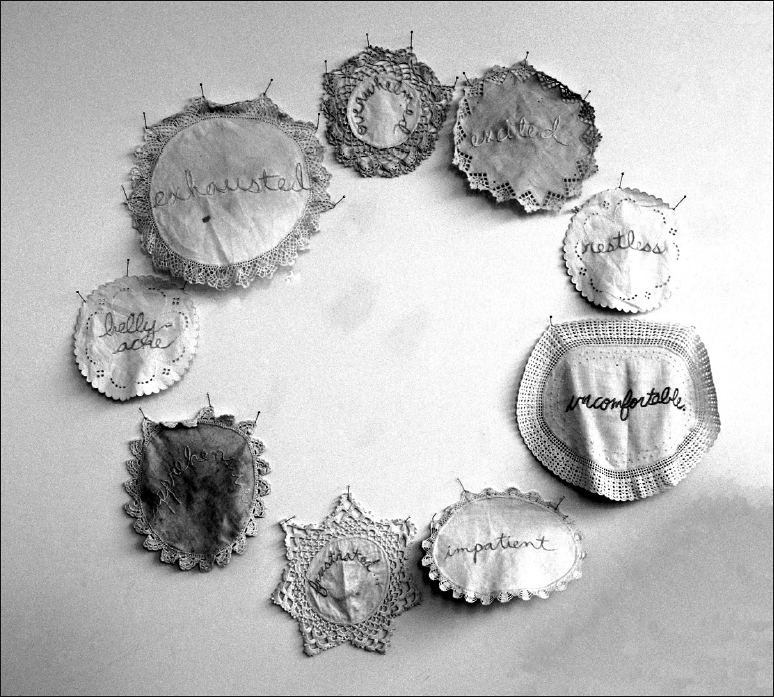

27 Maue seems to refuse the apparent emulative imperative of the sampler form, instead stitching disruptive or deeply personal words and rejecting the presentation of a coherent relationship to normative femininity. Often pairing short phrases or words with floral borders, Maue invokes the visual form of the sampler in her series “9 months,” which openly interacts with the sampler as inheritance (Fig. 4). The series features a collection of nine lace-edged handkerchiefs (and doilies), each embroidered with a single word: overwhelmed, excited, restless, uncomfortable, impatient, frustrated, apprehensive, belly-ache, and exhausted.14 Stitched during her pregnancy, these small pieces present an ambivalent, but committed relationship to the conceptual position of “handing down,” and the relationship between the stitch and the feminine, complicating the apparent singularity of her works.

Display large image of Figure 4

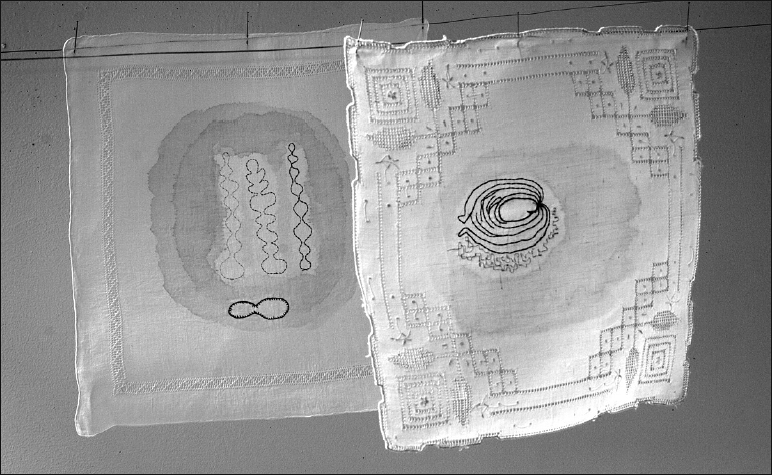

Display large image of Figure 4

28 These pieces are time-intensive, requiring hours of repetitive stitching, not the result of impulsive or careless action. Though her chosen words represent a complex and variable response to her pregnancy, and reveal the multiple emotions and felt responses to her state, the process of stitching is repetitive, the same with each pass of the needle. She draws a parallel between the labourious, tender, frustrating, pleasurable work of stitching and the embodied and emotional work of maternity. She stitches herself, often feeling lost and alone in the mess of motherhood, into community with other women who have stitched through these times. Though she chooses words that might not be found in conventional samplers, her work seems deeply aware that generations of women have also stitched their relations to kin, stitched in frustration and love, and used cloths to mop up the mess of life. Using materials often associated with the messiness of bodies, she calls attention to her own physicality and, though she stitches words, draws upon the unspeakable, affective connections offered by touch and mediated through textiles.

29 As Eve Sedgwick argues, “the sense of touch makes nonsense out of any dualistic understanding of agency and passivity: to touch is always already to reach out, to fondle, to heft, to tap, or to enfold, and always also to understand other people or natural forces as having effectually done so before oneself” (2003: 14). Moving outside of the space of articulations about the value of embroidery, its historical relationship to constructions, performances, and impositions of gendered identity, the realms of affect and touch allow for the “irreducibly phenomenological” experience of engaging with material and considering what might pass between bodies linked by shared media (Sedgwick 2003: 21). This reading attends to the felt histories that persist in materials, resisting the notion that a medium or technique might be made anew or fully detached from its context. Touch can be a site of ambivalent interaction, creating places where material histories and bodies interact and spark messy feelings and unpredictable senses of connection or disconnection. But these makers all highlight the importance of the “handed down” quality of their materials, viewing them as places where they at least seek to feel the past. As these makers use needle and thread to pierce vintage cloth, they enter into relationship with historical methods, media, and, perhaps, makers.

30 Sheena Vachhani further highlights the ways in which crafted and vintage objects become particular loci for affective forces and connections. Exploring such practices as knitting and record collecting to emphasize the centrality of tactility in creating both social and imagined communities, she notes the ways in which material engagement sparks affective responses to objects imbued with the traces of past bodies. Touch enables “a more complex and multifaceted relationship between objects, cultural practices, identity and the debris of (forgotten) pasts,” moving beyond any simple sense of reviving, reclaiming, or subverting a historical practice (2013: 93). Rather than referencing and/or reworking a history, the medium of the vintage handkerchief allows these stitchers to instead participate in the making, uncovering, continuation, and stewardship of a material and performative archive, unbound by time. In elaborating upon historical or nostalgic objects, these needleworkers participate in a dialectical relationship, extending the ways in which touch, as Steven Connor writes, “acts upon the world as well as registering the action of the world on you” (qtd. in Vachhani 2013: 94).

31 Maue’s piece, Touching, features two handkerchiefs connected by frayed threads emerging from finely stitched hands, their fingers disintegrating at the tips, spilling beyond the frame of the handkerchiefs (Fig. 5). The linens are stained and their surfaces marked by both signs of normative, feminine beauty—bouquets of pink peonies and black-eyed susans frame each hand—and evidence of mess. The threads that connect the two handkerchiefs both suggest the possibilities of connection through materiality and also appear steeped in wistful desire: the hands will only ever meet through the tenuous connections of fragmented threads. Maue thus gestures towards the limits of cross-temporal connection through material objects. The thread does not just evoke, but also invokes the past—no single stitch works without calling up the legacy of those stitched before. The stains, the techniques, and the physical linens all seem to enable connection with past users and makers, but the content of her work suggests fragility and incomplete meetings. She reaches out and finds no firm connection, but a register of seemingly endless past touches mediated through needle and thread.

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5

Allison Manch: Intimacy and Public Exchange

32 Allison Manch also takes up the discourse of bodily traces in her work, though she is often read in a very different vein from Maue. Her work is also personal, as she tends to stitch words and emblems from the pop culture of the 1980s and 1990s—the period of her youth and adolescence. However, the pop culture nature of her art has prompted critics to view her work as engaging with fun and generational memory, rather than with deep emotion or domestic space, as Joetta Maue is typically read. In interviews, however, she reveals that she began working with handkerchiefs handed down to her from her grandmother. She says of her handkerchief canvases:

33 For her, the handkerchief is a charged material, infused with memory and resonances of home, female relatives, and potential connections with viewers.

34 Moving outside a simple reading of the literal content of her stitching, the canvas of the handkerchief becomes a site for nonverbally articulating a relationship to memory and to the ghostly, embedded presence of other bodies in the material of the cloth. Although her most famous works are considered part of the realm of ironic and subversive stitching, featuring lines from Dr. Dre or Jennifer Lopez’s songs, the broader stretch of her work and the felt meanings of her connection to the material reveal an earnest engagement with genre, medium, and a sense of lineage. Her early work featured “word portraits;” she would interview friends and family about their daily lives, pick a single quote from their conversation, and embroider it onto a handkerchief, revaluing the seemingly mundane or ephemeral with the time, labour, and concreteness of stitching (Pela 2008).

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 6

35 Pesto and Paper Cut, for example, displays quotes from two friends. Kristen’s words about her favourite and least favourite foods are rendered in a simply stitched cursive while Melissa’s anecdote about a paper cut she received at work is stitched in print (Fig. 6). Both quotes are attributed, concretizing Manch’s relationships with these women through the stitching of their names into the surface of the deep brown handkerchief, already decorated with densely worked floral motifs along the border. These seemingly trivial sentences about pesto, tomatoes, and moving work files from one drawer to another reveals an underlying sense of care and a commitment to the work of relationship. Manch logs intimate details of her friends’ lives and displays her care publicly; their names inscribed on her work. Her word portraits appear as inscrutable fragments of personal conversations, but they register intimate relationships in the public sphere and invoke the long history of the handkerchief as a love token, a material object used to “conduct and define personal and social relationships” (O’Hara 2002: 63). And, though many of the textiles that she uses do not align with period understandings of the handkerchief (particularly the form of the handkerchief that would have been understood as a love token), the force of her associations persist and structure both her encounter with the object and the audience’s entry point. Indeed, though the base fabric of Pesto and Paper Cut might more accurately be described as the kind of textile that would drape over furniture, Manch assimilates it as a handkerchief and, in so doing, invokes the handkerchief’s history as an intimate object of exchange.

36 Diana O’Hara reads the handkerchief as a social “intermediary,” their exchange and display enacting the construction of intimate relationships in the public sphere (2002: 115). Her work explores the use of the handkerchief in the late medieval and early modern period as a tool in the gift economy that facilitated the “making of marriage” (O’Hara 2002: 61). By the late 1890s, handkerchiefs, ubiquitous accessories expected of fashion-conscious women moving through highly differentiated social spheres of refinement and class, became explicitly codified as a means of non-verbal communication. These codes built on longstanding associations between romantic courtship and the handkerchief, stretching back at least as far as the 1500s in England, when John Stowe wrote that:

37 Handkerchiefs became tokens of romantic commitment—or at least interest—linking the handkerchief both with feminine honour, promised remembrance, and material signals to the outside world.

38 Other scholars have noted the potentially feminist uses of the handkerchief, in particular, as a love token. While many of these gifts were exchanged between men, securing male relationships through the circulation of money, objects, and women, it is significant that handkerchiefs constituted about a third of gifts exchanged to establish formalized or public courtship relationships and were a form of courtship tokens that women tended to give, allowing them to act as what Juana Green calls “erotic agents” (2000: 1085, 1096). These handkerchiefs revealed their bearers to be relationally constructed selves, but also created space—through their decoration—for the expression of more personal, self-determined sentiments.15

39 While Manch’s word portraits and pop culture references do not explicitly engage with the terrain of the romantic, they most certainly demonstrate a public self constructed through relationship and social exchange. Taken in this context, her pop culture references become resignified as deeply personal memories; her handkerchiefs function as tokens that concretize moments of relationship—whether to kin, friends, or pop cultural icons. 16 Although they might be more broadly relatable than her earlier works, her process is still intimately engaged with the nature of memory, ephemera, and rendering the disposable into an archive. The handkerchief, the ground of Manch’s labour, continues to anchor her work in the world of personal remembrance and embodied connection to past generations of women who have stitched their own cultural references, their own expressions of care for kin. Her concretization of apparent trivia and moments of exchange in the daily course of intimate relationships calls upon Muñoz’s work, asserting the value of the seemingly fleeting and the deep importance of feminized attachment.

40 Manch illuminates the ways in which an exploration of and participation in a seemingly limited, out-of-reach archive of women’s making might be rendered possible at the level of material, rather than content. Manch writes that “the imperfection and vulnerability of the embroidered line resembles the fragility of human emotion, while the medium harks back to a seemingly distant past” (qtd. in Maue 2009). The content, her seemingly modern update of embroidery featuring rap lyrics and pop culture icons, is not the site of revision, though it plays with notions of the sampler form and the question of the relationship between labour and meaning. Instead, the felt—both on the level of the emotional and the tactile—connection to fabric and thread is what enables some form of connection to a “seemingly distant past,” opening up new possibilities for contemporary work and for understandings of and feelings for past work.

Ke-Sook Lee: Memory and Coded Communication

41 Manch’s deeply personal handkerchiefs often refuse to announce the meanings hidden behind their construction and instead offer a cryptic phrase about enjoying mashed potatoes or one’s grandmother’s recipes in place of a legible, transparent document of an affective relationship (Manch 2005). Similarly, Ke-Sook Lee’s exhibit, One Hundred Faceless Women, displays handkerchiefs as coded references to unintelligible—or simply publicly inarticulable— meanings and sentiments. As such, both invoke the history of the handkerchief as a tool of coded performance and strategic visibility. Their work is partial, resisting transparency.

42 Revealing the history of the handkerchief as a token of affection and commitment, in 1877 Daniel R. Shafer wrote that “the handkerchief, among lovers, is used in a different manner than its legitimate purpose. The most delicate hints can be given without danger of misunderstanding, and in ‘flirtations’ it becomes a very useful instrument. It is in fact superior to the deaf and dumb alphabet, as the notice of bystanders is not attracted” (230). The “hanky code” of the late 1890s and early 1900s established a performative series of meanings that the display of handkerchiefs might convey—though these codes were often shifting and one could not necessarily rely upon accurate interpretation. Helen Gustafson writes of one such list of codes from about 1905, which communicated such various meanings as “I am engaged,” “we are watched,” or “follow me” with handkerchiefs “winding around forefinger,” “drawing across forehead,” and “over the shoulder,” respectively (2002: 34).

43 The hiddenness of these codes was often more performative than lived, as newspapers would publish these lists. An 1869 issue of the Journal of the Telegraph, for example, laid out an extensive list of coded meanings, claiming that folding one’s handkerchief suggested the desire to speak with an observer, “taking it by the centre” indicated unspecified “willingness,” and placing it over one’s right ear meant “you are changed” (45). By 1871, novelty books detailing the codes of handkerchief, fan, and parasol flirtation were produced in the shape of fans and disseminated widely (see Fisher 1871). Regardless, the handkerchief functioned as a material means of women’s signaling of romantic interest or lack thereof, perhaps particularly useful in a social climate that discouraged overt, public discussions of romantic and sexual preferences, and often figured women as romantic conquests and possessions rather than agents. This historical social function, communicating romantic and sexual desires inarticulable in public spaces, has marked 20th and 21st-century parallels. In San Francisco in the 1970s, the practice of “flagging” (also known as the “hanky code”) arose. This practice enabled the coding of a wide variety of sexual preferences and statements of availability, materialized in the placement of different colored handkerchiefs in one’s back pocket. Both openly visible and clearly covert, the handkerchief signalled both belonging to a community and an individual’s specific interest in a set of behaviours. This later meaning of flagging has continued into the 21st century, a queer politics of coded visibility.17 Handkerchiefs thus became double objects, able to carry the weight of multiple significations and speak to varying audiences. Implications of intimacy became visible in the public sphere, albeit through thinly veiled codes.

44 Ke-Sook Lee plays with this concept, literalizing the notion of airing one’s laundry in her exhibit, One Hundred Faceless Women, and plays with ideas of intelligibility, coded signs, and personally felt meanings (Fig. 7). The exhibit features one hundred vintage handkerchiefs, collected over Lee’s lifetime, hung on clotheslines and embroidered with “cryptic, semi-abstract narratives” that she attaches both to her own experience of femininity, the space of the domestic, and to broader experiences of gendered bodies and lives (Kirsch 2012). Although Lee’s stitchings are not readily legible, she argues that the felt experience of stitching and the medium of the vintage handkerchief serve as mediators; they “bridge ... the gaps between generations of women. So much of our experiences as women are found in textiles” (qtd. in Kirsch 2012). Like many of the other needleworkers discussed, Lee works with the handkerchief for its significations of disposability, bodily traces, and feminine performances of propriety. She positions herself as a storyteller, using needle and thread to give voice to a seemingly silent narrative. Elizabeth Kirsch writes that Lee’s work seems to materially invoke “the whispers of countless anonymous females of all ages. One can almost hear the polyphonic utterances of those who fashioned the delicate, hand-made handkerchiefs” (2012). As each of the stitchers discussed have shown, Lee never stitches alone. Though her work is idiosyncratic and specific, it is also intimately engaged with a sense of heritage and materially constituted community.

Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 7

45 Her works are not literally true or recorded stories, however, but personal codes and abstract signs (Fig. 8). The framing text to her exhibition catalog makes it clear that Lee seeks to both participate in, and reformulate, an ambivalent tradition, one that she casts, by turns, as beautiful and painful. Trying to sort through her own experience as a stay-at-home mother, she found both comfort and shared frustration in a sense of the “historic aspect of female labor” in the space of the domestic (Kirsch 2012). This shared sense, however, had to take place on the level of personal imagination, the abstracted code, and the tactile, due to the limits of the verbal, historical record. For Lee, connection—though not resolving an underlying sense of discontinuity—was sparked through touch, not clearly articulated or heard stories. About the vintage handkerchiefs themselves, she says: “I like that they belonged to certain women and were used many times to touch faces” (qtd. in Kirsch 2012).

Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 8

46 Those faces, those bodies, are not clearly accessible to her as known entities, but inhere in physical objects, enabling an engagement with those “intensities that pass body to body (human, nonhuman, part-body, and otherwise), in those resonances that circulate about, between, and sometimes stick to bodies and worlds” (Gregg and Seigworth 2010: 1). Illegible, inarticulable, and deeply felt, these stories transform into evocative forms and symbols that hint towards accessibility, but hover just outside of clear interpretation. Indeed, they complicate a sense of any possibility of direct reading, calling up shifting, layered, and often inconsistent meanings. The artist, the apparently singular maker, is only partially in control of the work. Through her inventive and innovative work, Lee also cedes some of the power of the individual artist, demonstrating the sedimented meanings that accrue to these material objects and work on the bodies and histories of each viewer.

Making and Made By the Archive: The Recursive Stitch

47 Stitching into the surface of vintage handkerchiefs, looping in, through, and around a cloth that has been touched and punctured many times before, these needleworkers participate in, and revalue, an archive of making. As Nelson’s memory-cloths reconfigure the status of memories, Maue’s ambivalent works demonstrate the interplay of labour and pleasure, the possibilities and frustrations of connection with others. Manch’s word portraits work to fix the momentary and the trivial, and Lee’s “faceless women” constitute and render visible the limits of a feminine history. Together, they posit a challenge to stable, unidirectional passages of time and sense. I read these makers as intervening on an unwritten archive, attempting to place themselves in cross-temporal relationship with unknown makers and out of reach histories. This reading is guided by queer theory methods, such as those outlined by José Esteban Muñoz, Eve Sedgwick, and Elizabeth Freeman. Each of these scholars engages with the limits of the archive and illuminates some of the ways in which subjects seek connection to unwritten, imposed, hidden, or painful histories in ways that still provide space for love, beauty, connection, and pleasure. Freeman, in particular, in her work on “erotohistoriography” insists on these practices as survival strategies (2010: 59).

48 I am wary of collapsing the categories of queer and feminist, especially as none of these artists mark their work as queer in terms of content, but the ways in which these contemporary needleworkers position their relationships to materiality, time, gendered subjectivity, and desire do function to queer the archive of women’s history, the linearity of history, and dominant narratives about needlework. They posit the possibility of engaging with a feminine inheritance without adhering to essentialized understandings of womanhood or strict notions of the temporality of passing down. The looping stitches of thread, passing through cloth infused with a sense of past bodies, selves, stories, pleasures, and labours, constitute “binds” that, as Freeman argues, might “make… predicament into pleasure, fixity into a mode of travel” (2010: 61). Through the repetitive act of stitching into these past-laden swaths of fabric, contemporary needleworkers explore the ways in which one might find an ambivalent pleasure in historically imposed activities, how the irrevocable puncture of the needle might constitute an intervention on the narrative of history, a refiguring of the material contents of the archive, an interruption through the repertoire, and a moment of felt engagement with a tactile, historical community. In this way, both the past and the contemporary stitcher are rendered permeable, laid open to cross-temporal influences and sensory forces through engagement with physical material. These cloths are therefore both archives of embodiment and prompt an embodied response.

49 Nelson, Maue, Manch, and Lee’s works all index a past—the handkerchiefs are referred to as “vintage,” “reclaimed,” or “donated”—and also intervene on it, implicating the contemporary maker in an ongoing, interactive relationship rather than a simple reaction to a history, a passive inheritance. In so doing, these stitchers both claim and co-create an archive of seemingly disposable, but pointedly preserved, objects. These needleworkers construct spaces of intimacy, connection, longing, and ambivalence, using the historical meanings of the handkerchief to explore the broader meanings of women’s work and community. Historically embedded in discourses of remembrance, covert and public signaling, embodiment, relational identity, and affective exchange, handkerchiefs illuminate the possibilities of transhistorical connection. The vintage handkerchiefs in each of these stitchers’ pieces function as a way to bring the abstract, often anonymous narrative of embroidery’s feminized past into the realm of the personal, the remembered rather than the historical, and the affective space of touch. Destabilizing the confident detachment and uncomplicated assertions of agency embedded in ironic, subversive stitchery, these needleworkers acknowledge the fundamental ensnarlment of selfhood with past understandings of identity, with material realities, and with the full, complex, and inarticulable inheritance of gender as it has been performed. Their interventions on the medium of the vintage handkerchief might be read, then, as revealing an entangled agency, one always engaged with the accretions of the past. And that entangled agency is the ground on which feminist nostalgia might be built.

50 These four makers are all using the handkerchief in order to talk about a feminine relationship both to embroidery and to a sense of nostalgia or pastness—especially in relationship to feminine identity and material production. They also raise ideas of coping with a sense of gendered discontinuity, especially in their insistence that handkerchiefs might help “bridge the gap between generations of women,” as Ke-Sook Lee argues. They suggest that these tactile encounters might provide connection that is otherwise unspoken or unspeakable. Rather than embracing the feminine, rejecting it, or adopting a kind of post-feminist, ironic stance, these needleworkers engage with historical femininity as an archive of performances—not as an identity.

51 Historical performances become substances that are sedimented in material objects, the “stuff” of femininity. These stitchers tap into that performative archive, and a history of touches, actions, and affects are rendered accessible—albeit always partially, through gaps, evocations, and invention—through vintage cloth and repeated movement. A critical, feminist nostalgia acknowledges the limitations and inequities of the past and, yet, seeks to make space in which to engage with its particularities, feel its weight, experience the oft-thwarted desire for connection, and enter into creative relationship with it. Making and made by this performative archive, these stitchers reveal a feminist nostalgia that holds space for mess, desire, mourning, connection, and absence and refuses a passive vision of inheritance. Through material acts and through materiality itself, these makers deconstruct and reconstruct feminine history, registering it as an archive of gestures, of affects, and of charged matter. The stitched handkerchief is a potent site of access into that record. It is a historical site for social performance, bearing a legacy of more and less legible communication, calls to remembrance, anxieties over the mess of matter, and deeply gendered relationships to materiality, memory, history, and community. Stitching into its surface, reformulating its physical form, these makers intervene in history and the performative, feminine archive in a physical, felt fashion. They create space for the earnest, material engagement with complex, often ambivalent, linkages between the performance of feminine identity and social cloths—all marked by needle and thread.