Research Reports / Rapport de Recherche

Fit for a Sultan:

An Investigation of an Ottoman Cairene Carpet in the Collection of the Nickle Galleries

1 This paper examines an Ottoman era carpet that has changed tremendously throughout the course of its life. In its current diminutive form, it is part of the Nickle Galleries textile collection at the University of Calgary. What did the original carpet look like, and how can we find out? What factors may have helped its survival? Through a careful observation of the piece and a search for related fragments, we argue that this carpet was most likely part of an enormous textile that may have been originally used at the Ottoman court. Moreover, it may have been woven in the late 16th to early 17th century, which may explain why it was a sought after piece. At some point during its life, the decision was made to cut and sell the larger textile to individual collectors and museums. It may have been sold to be used as a wall hanging, a small area carpet, or even as a prayer carpet, although this is unlikely due to its design.1 We therefore refer to the Nickle artifact as a “carpet fragment” rather than a carpet, even though it can be used as a carpet in its current form (Fig. 1). This paper uses a wide array of sources to find missing pieces and traces the origins of the carpet. It proposes a reconstituted original carpet using evidence found in museums worldwide. We also attempt to explain why such a valuable artifact would end up in pieces scattered around the world.

Curatorial Context and Research Methods

2 The Nickle Galleries house around one thousand artifacts in its textile collection, the majority of which are knotted pile carpets from West and Central Asia.2 Although the piece we are investigating is only a fragment of a larger textile, the gallery’s textile curator, Michele Hardy, nevertheless views it as one of the most valuable artifacts in the collection.3 The carpet fragment (NG.2014.110.000) was part of a donation made in 2014 by Dr. Lloyd Erikson, a collector with a unique passion for West and Central Asian carpets.4 Erikson purchased the carpet fragment in 2006 for £24,000 at a Sotheby’s auction in London. Records attached to the artifact inform us that it was sold in Lot 42 from a f amily collection, and was described at the time as a “Cairene carpet border fragment, Ottoman Egypt.”5 While this type of carpet is typically referred to as an “Ottoman Cairene” carpet, it may also be called an “Ottoman-court” or “Turkish-court” carpet, or a “Damascene” carpet, due to speculation about the origin of these types of textiles, and depending on the date of the publication.6

3 This paper was facilitated through direct access to the piece, but also through an examination of a variety of comparable textile artifacts available at other institutions. The Nickle carpet fragment was directly accessed and photographed by Yara Saegh in the summer of 2017 to complete the descriptive section of this paper that focuses on the material evidence presented in the artifact. This evidence is then considered through deduction and speculation exercises that ultimately lead to an in-depth contextualization and reconstruction of the piece. As part of a university collection, closely investigating such an artifact and questioning the knowledge around it is an important task in the curatorial evolution and understanding of the object.

Ottoman Cairene Carpets: Introduction and Main Features

4 Carpets are objects with long and complex histories within the cultures that produce and use them. In How to Read Islamic Carpets, Islamic Art historian Walter B. Denny states that “for as long as they have been a documented part of the material culture of the Middle East, carpets have also been part of the material culture of the European—and ultimately North American— West” (2014: 129). The western fascination with carpets, which has been termed “Ruggism,” has created a rich subject of study for scholars in a variety of fields who have investigated carpets and their impact on Europe and North America (Barnett 1995: 13-14; Spooner 1986: 95-215). While there are many surviving artifacts (textiles and a variety of documents, some dating as far back as the 14th century) that bear witness to the evolving history of carpet production and consumption, this research focuses on reconstructing the life story of one particular artifact (Denny 2014: 129). We analyze the Nickle carpet fragment in order to understand the material, utilitarian, cultural, and artistic values that may be embedded in this artifact (Prown 1982: 3).

5 The type of carpet under study is generally referred to as “Ottoman Cairene” because conventional contemporary scholarship establishes its origins in the Egyptian city of Cairo or its surroundings during the period of Ottoman rule (Denny 2014: 47-48; Sarre and Trenkwald 1926: 12-14; Thompson 2006: 164;). However, the attribution of its beginnings in other regions has been suggested and is controversial among scholars. Recent evidence argues that carpets labelled as “Cairene” may have been produced at the Ottoman court-weaving centers in Istanbul or Bursa by Egyptian weavers, or even in textile-weaving centers in the southern regions of Syria.7 The ambiguity of their origins has existed for as long as these carpets have been documented and examined, and may explain why some early scholarly publications describe these textiles as “Ottoman-court” carpets or “Turkish-court” carpets, and older European sources sometimes referred to these carpets as “Damascene” (Sarre and Trenkwald 1926: 13). The carpet type is present among the textile collections of European, North American, and Middle Eastern museums.

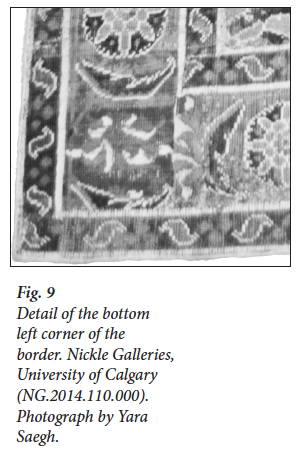

6 Ottoman Cairene carpets feature stylized flowers, the most noticeable being a serrated leaf motif that characterizes and lends its name to the “saz style,” frequently seen in contemporary Ottoman art of the 16th and 17th centuries (Denny 1983: 103-104; Thompson 2006: 175). In addition to the saz leaf, this type of carpet features stylized palmettes, rosettes, hyacinths, tulips, and carnations, as well as stylized vegetal stems that are usually laid out in medallion designs (Boralevi 1987: 26; Denny 1983: 103-106; Thompson 2006: 175). These features are distinctive and are obtained via a weave and yarn structure that is also seen in “Mamluk” carpets, a name used to describe the dynasty that ruled Egypt and Syria from 1250 to 1517 and ended with the Ottoman Turkish Conquest. Mamluk carpets, however, present geometric designs, rather than intricate foliage and floral motifs, and were woven in a subdued pastel palette that was usually restricted to three colours (Suriano 2004: 94-97). The place of origin of Mamluk carpets was considered a mystery until the early 20th century when archeologist Friedrich Sarre traced their roots to Mamluk Egypt (Sarre and Trenkwald 1926: 10-11). The comparable production processes involved in Ottoman Cairene and Mamluk carpets have led to debates regarding their ancestry.

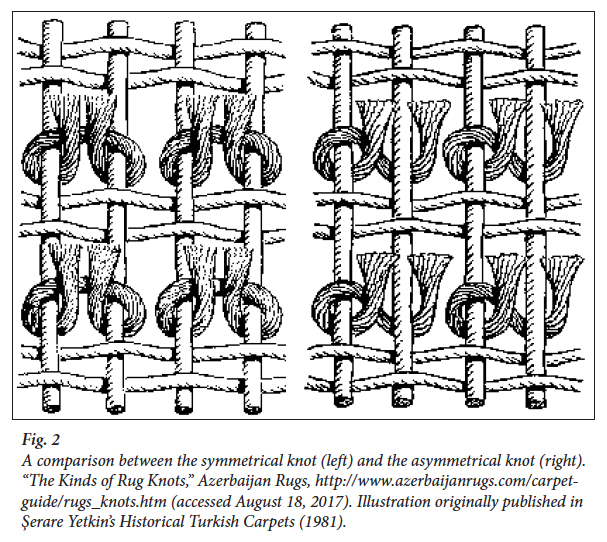

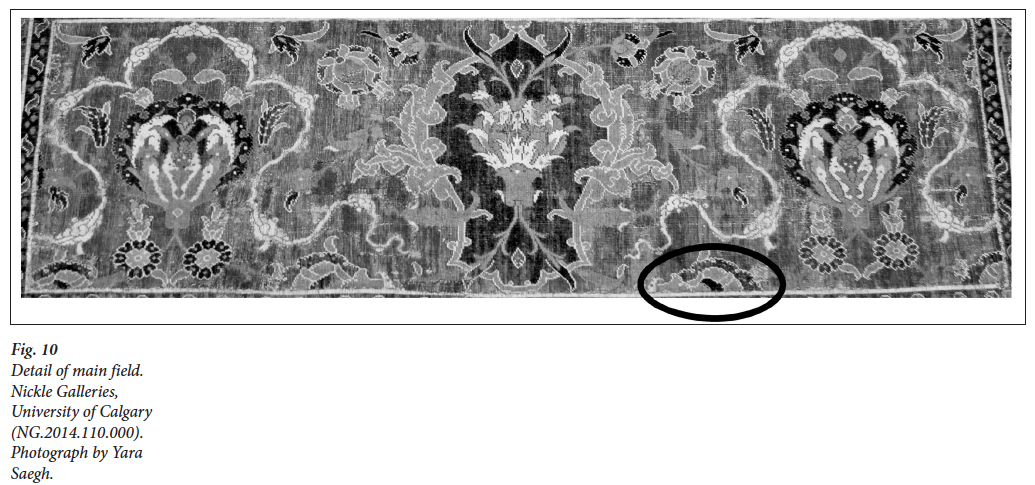

7 In his book on Ottoman carpets, Italian carpet expert and dealer Alberto Boralevi elaborates on the weave structure of Ottoman Cairene carpets, which, at the start of the 20th century, was discovered to be different from Anatolian and Persian carpets (Boralevi 1987: 26). Boralevi explains that, unlike Anatolian rugs, Ottoman Cairenes are knotted with an asymmetrical knot—called a “Senneh knot”—that is open on the left side, and allows for a better depiction of curvilinear lines and more details (see Fig. 2, right) (Boralevi 1987: 26).8 While the two ends of the yarn are lumped together in a symmetrical knot to form a large visual pixel, the ends of the yarns are seperated in an asymmetrical knot to form two smaller pixels that allow more details. Moreover, the wool yarn of Ottoman Cairenes is “S” spun, a technical term that defines the conversion of fibers into yarn “according to the direction of the diagonal of the twist which one sees observing a single strand of yarn”—as opposed of the “Z”-spun yarn of most other carpets, with the exception of Mamluk carpets, which also use of asymmetrical knots and S-spun yarns.9 Textile scholar Jon Thompson, like most authorities, traces Mamluk carpet production to Cairo, but Carlo Maria Suriano has tried to link stylistic and historical evidence that attributes their production to Syria instead (Thompson 2006: 164).10 The verdict is therefore divided as to the place of manufacture of Ottoman Cairene carpets, as they are generally believed to have been produced either in Cairo or at the Ottoman court production centres in Istanbul and Bursa by Egyptian weavers (Denny 2014: 76; Thompson 2006: 172).

Nickle Carpet Fragment: The Material Evidence

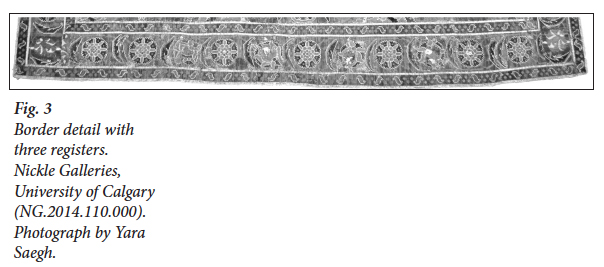

8 The artifact under study consists of several different joined pieces, which give the appearance of one cohesive design and carpet. The inspection of the back of the carpet is unmanageable because of a linen backing that was sewn to it when it arrived at the institution. Although this backing may be a form of reversible conservation treatment and is helpful for the purpose of displaying the carpet in the safest way possible, it makes it difficult to inspect the exact areas where the different pieces are sewn together. The overall dimensions of the patchwork artifact are 156.5 cm long by 68.5 cm wide. The design consists of a subdivided border and a main field. The main field’s dimensions are 125.5 cm long by 37.5 cm wide. The artifact has a top and a bottom according to the direction of the motifs in the main field. The border is comprised of three registers: two narrow registers of approximately 4 cm each and one middle register between them of about 7.5 cm (Fig. 3). Based on visual and tactile access to the artifact, the pile is understood to be mostly made of wool. The presence of cotton yarn can be felt in the pile where the colour white is used. Lack of access to the back does not allow cursory fiber identification there. Very closely related fragments from other collections, presented later in this paper, have a silk base (warp and weft yarns), to which the wool and cotton pile is knotted in asymmetrical knots, a weave structure present in our artifact.11 As stated previously, the pile is made of “S”-spun yarns. There are seven colors in the Nickle textile: red (the ground colour), two shades of green, two shades of blue, white, and yellow. No record of laboratory analysis was found for this artifact. Within the confines of this study, we could not commission such tests as tomography (CT) imaging to investigate the assembly of the fragments, nor could we obtain small clippings for fiber identification and chemical analyses to find out if natural or artificial dyes were used.

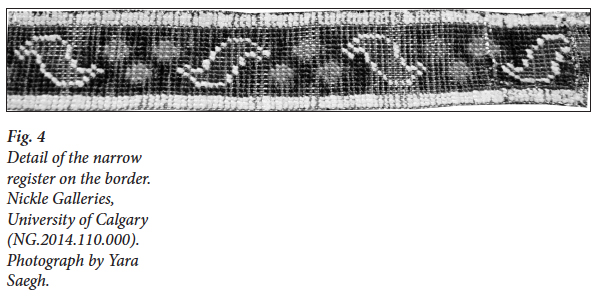

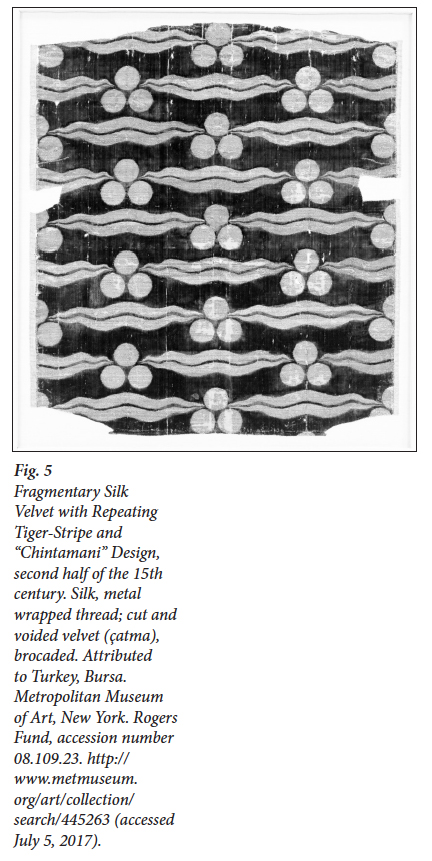

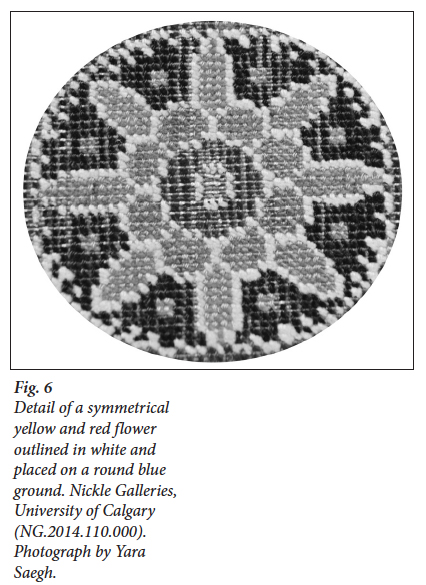

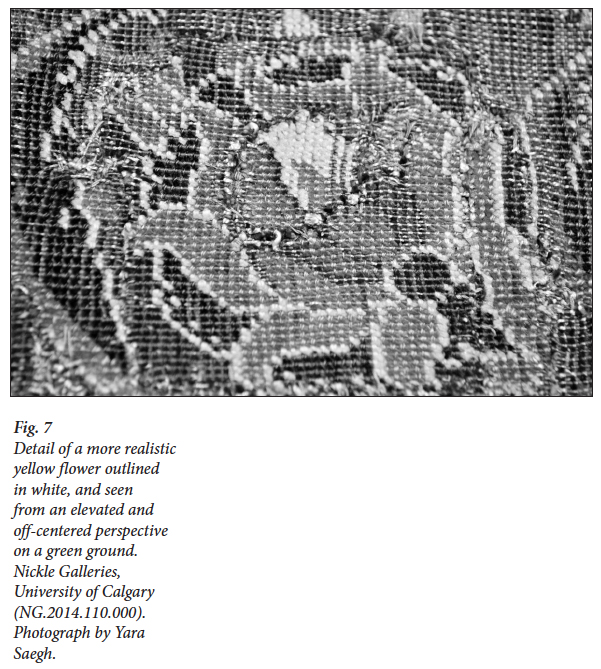

9 The two narrow registers of the borders are similar, while the broad register in the middle has more varied motifs (Fig. 3). The narrow registers are outlined in white and filled with motifs of mirrored red stylized leaves also outlined in white (Fig. 4). In between these leaves are three spherical yellow motifs outlined in red, a grouping that is a recurring theme in Ottoman Cairene carpets and was very popular in Ottoman Turkish art (Fig. 5) (Denny 2014: 75).12 This grouping with a kind of wavy band is called chintamani, a motif that may have originated from Buddhism and means “auspicious jewel” in Sanskrit (Denny 2014: 123). It made its way to Anatolia where it came to serve as a good luck or apotropaic symbol (Denny 2014: 123). It may also be a representation of the heraldic emblem of the Turco-Mongol conqueror Timur (also called the “Coat of Arms of Tamerlane”) (Boralevi 1987: 26). On our artifact, the alternating motifs on the narrow registers are laid on a green background.13 The broad middle register consists of alternating motifs. One is a symmetrical yellow and red flower outlined in white and placed on a round green ground (Fig. 6). Another motif is a more realistic yellow flower outlined in white (possibly a tulip), seen from an elevated and off-centered perspective on a green ground (Fig. 7). Each of these floral motifs is separated by one or two stylized and curved green serrated leaves that are outlined in white (Fig. 8). These floral and leaf patterns on the broad middle register of the border are set on a red background.

10 The subdivided border seems to be created out of pieces that have been attached to each other. The artifact lacks purposely-made corner sections. This may indicate that the patchwork pieces that create the border were once part of a longer border on a much bigger carpet. There are many stitches (restoration or assembly) visible that are heavily concentrated at the bottom and side border sections. Pieces have been inserted in small and large sizes to create the patterns, such as in the floral motif in the bottom left corner of the border (Fig. 9), where the pile knots are in visibly better condition than their surroundings.

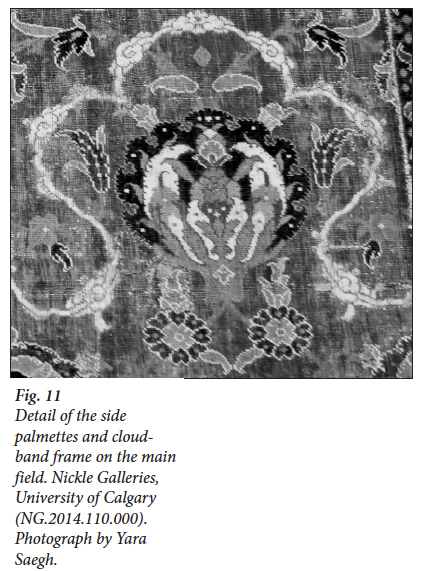

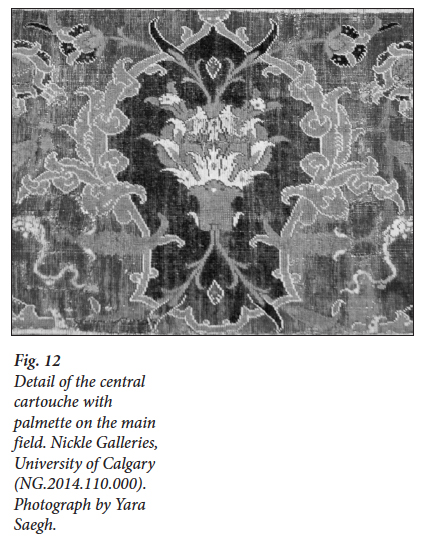

11 The main field is characterized by a central cartouche with a small palmette and two larger identical palmettes on both sides of the cartouche (Fig. 10). All palmettes are symmetrical on the right and left but not on the top and bottom. The central one is placed on a larger contrasting green ground. The two side palmettes are quite elaborate in design (Fig. 11). They consist of a series of motifs: at the base are two symmetrical floral motifs (dark outer edge with yellow center) with yellow leaves springing from their upper sections. They are placed below a larger yellow flower with pistil and white stamens from which other floral and leaf motifs sprout to the right and left sides, each creating more floral motifs. The palmette is also surrounded by other flower and leaf motifs and white “cloud-bands” that form a three-lobed frame around the palmette. These scrolling white three-lobed devices may be similar to Chinese cloud-bands. Although not very common in Ottoman Cairene carpets, the presence of cloud-bands in some Anatolian artifacts is not surprising because certain Chinese motifs, such as the dragon, phoenix, and lotus also influenced some Near Eastern crafts and the development of their artistic culture.14 The carpet’s central palmette is set on a cartouche with a green background and elaborate yellow vegetal borders with white outlines (Fig. 12). Two shorter floral stems also spring from the top and bottom of this palmette. The three palmettes on the main field are connected with one another at their bases by floral stems and partial palmettes (circled in Fig. 9) that run by the bottom section. The spaces in between are filled with vegetal and floral motifs that are all set on a red background.

12 The artifact is well worn overall, but the cotton pile is slightly less abraded than the wool pile. Most of the wool pile is somewhat abraded and the colours have faded. The red ground in particular has suffered a lot of damage. The subdivided border on the long side above the palmette motifs is in a slightly better condition than the one at the bottom. The upper border has retained a more vivid color and the pile is somewhat less abraded. The green colour on the narrow registers at the bottom border and the green colour of the ground at the central cartouche are, in many places, completely abraded to a point that the red weft of the ground fabric is visible. Despite all this, the artifact is remarkably preserved for its age as sources indicate that Ottoman Cairene carpets were produced between the early-16th and the late-17th centuries, and, as such, the artifact might be around 400 years old, which can help explain its overall condition (Boralevi 1987: 26; Denny 1983: 103-106; Ydema 1991: 19).

13 Nothing in the artifact’s records addresses its history prior to its sale at the Sotheby’s auction in London in 2006. As is typical for such pieces, assessments regarding their origins have thus been hypothetical and based on the examination of their material composition and structure as well as their design features. The asymmetrical knots with an “S”-spun yarn (unique to Egypt and some Syrian and Mesopotamian production centres) as well as the Asian-influenced motifs, such as the serrated leaf (saz style), palmettes, tulips, Chinese cloud-bands, and chintamani, all suggest that the Nickle carpet fragment is indeed a type generally referred to as “Ottoman Cairene” in carpet classification literature.15 Equipped with a thorough observation of the artifact and with the help of primary and secondary sources, we will now proceed with our own hypotheses on this artifact.

Historical Contextualization

14 Given their origins in the 16th and 17th centuries, Ottoman Cairene carpets are highly prized artifacts. Less than a hundred of them have been preserved to date.16 Those that are known today come from European collections, as they were valued and collected there for centuries, just like many other West and Central Asian carpets (Ydema 1991: 19-24). It is interesting to note that, according to carpet expert Onno Ydema, Ottoman Cairene carpets were not featured as often as other rugs in European paintings of the 16th and 17th centuries. This could be due to a reported decline in interest in representing carpets in paintings by the time they were being made and imported to Europe through Italy, around the middle of the 16th century.17 Some pieces were discovered only recently after having been stored away in palaces or churches for centuries. This is the case for the Ottoman Cairene and Mamluk carpets from the Medici collection that were found hidden in the basement of the Pitti Palace in Florence in 1983, and are documented in the palace’s original inventory as first arriving at the palace in the late 16th century (Spallanzani 2009: 94; Thompson 2006: 165).18

15 Ottoman Cairene carpets are valued today for their exquisite craftsmanship, artistry, and complex history. Aside from their predecessors, the Mamluk carpets, no other carpet type combines the asymmetrical Senneh knot with the “S”-spun wool yarn in their fiber use and weave structure. As mentioned earlier, this combination may have allowed curvilinear lines to be depicted in a smoother, more organic, and naturalized way (Ydema 1991: 21). Since the stark geometric forms of the Mamluk carpets were not as popular but the weaving skills of their makers continued to be highly appreciated, Ottoman rulers commissioned weavers of Mamluk carpets to make pieces with more vegetal and curvilinear designs that conformed to Ottoman tastes, which the conquerors had developed through their migration from Central Asia to Anatolia (Boraveli 1987: 26; Thompson 2006:167-72; Ydema 1991: 21). Ottoman Cairenes are thus instantly recognizable hybrids that are different from Anatolian and Persian carpets, yet carry elements from both of these carpet types. Thompson, in Milestones in the History of Carpets (2006), presents several reasons as to why the Ottoman court may have commissioned Cairene weavers despite having their own carpet-production centres in Ushak and Istanbul. One reason may be that, between the mid to the late 16th century, Turkish production centres were fulfilling a large commission by Sultan Selim II for a new mosque to be built by renowned architect Sinan in the city of Edirne.19 The ruling elite could also have preferred the fine Egyptian products for their court carpets (Thompson 2006: 167-72). The Nickle artifact’s survival, then, may speak about the history of taste and the preferences of rulers in the 16th and 17th-century Ottoman Empire (Denny 2014: 76-79; King and Sylvester 1983: 79; Mack 2002: 12).

Artifactual Comparisons

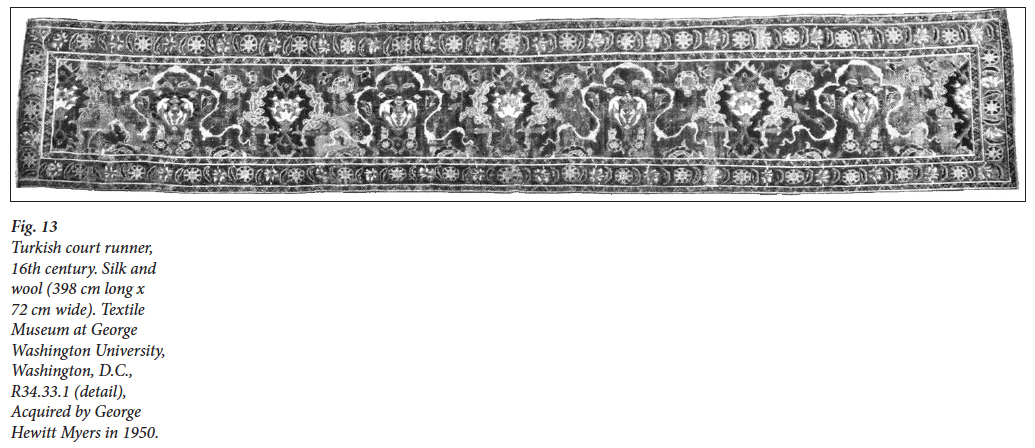

16 The Nickle artifact is similar to other pieces in other collections. A comparable artifact is located in the Textile Museum at George Washington University in Washington, D.C., but is slightly less than three times longer than the Nickle artifact (Fig. 13).20 In The Splendor of Turkish Weaving(1973), textile curator and Islamic art specialist Louise Mackie describes the Textile Museum’s artifact as a late 16th-century “runner” with silk warps and wefts, “S”-spun wool pile, asymmetrical Senneh knots, 3.98 m long and 72 cm wide (61, 75). 21 Mackie’s hypothesis is that the fragment was woven lengthwise, noting that that this long and horizontal dimension is quite unusual. Although she notes that there are many repairs to the artifact, and, on one side, the border had been completely sewed on, she doesn’t make any reference to the possibility that the entire piece could be a part of a much larger carpet.

17 If we compare the Textile Museum and the Nickle pieces, we can observe how both have the same stylistic features described in detail above. As a result, we can speculate that these two artifacts may have been made by the same weaver or produced in the same workshop, quite possibly at the same time. Judging from the 72 cm width of the Textile Museum piece compared with the 68.5 cm of the Nickel piece (the 3.5 cm difference can be reasonably attributed to the patching processes, wear and tear, and the production process that involves a variety of weavers who may conduct their work with slight differences) and the proportions of the motifs to each other, the Textile Museum’s “runner” could even be a longer border fragment of the same carpet that the Nickle artifact came from. The long and narrow dimensions of the Textile Museum’s piece may be indicative of how this artifact was used in its second life.

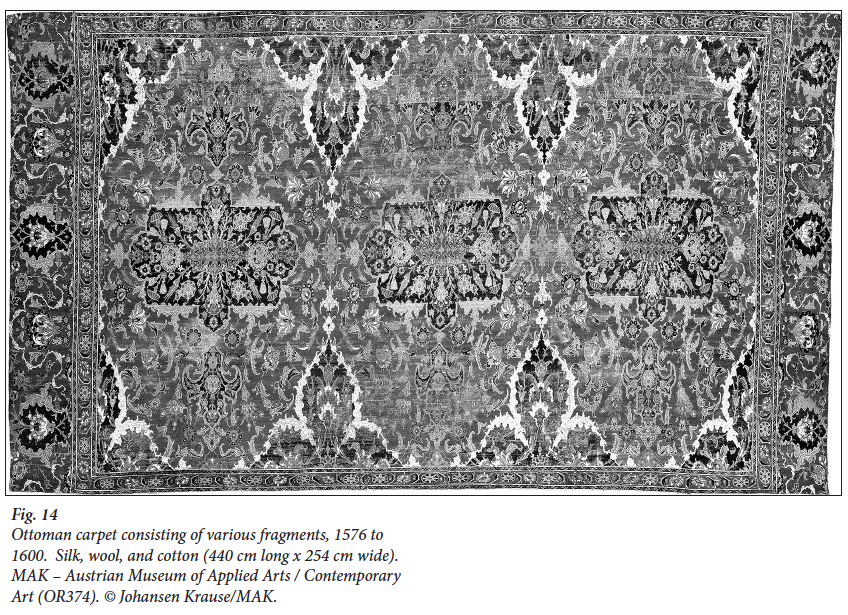

18 Another comparable artifact to the Nickle and Textile Museum pieces is a much larger knotted carpet (440 cm long by 254 cm wide) at the Austrian Museum of Applied and Contemporary Art (MAK) (Fig. 14).22 The MAK artifact is described online as a fragment of an “Ottoman carpet/rug,” and is dated 1576 to 1600. It is described as being made of “silk (chain), silk (shot), wool (flower), cotton (flower)” using an asymmetrical knot technique. It has an intricate main field (not seen in the Nickle and Textile Museum pieces) composed of a wide array of floral motifs and several cartouches and quatrefoil medallions that are, at times, cut by the border. At the left and right sides of this main field are borders relevant to this research as they are very similar to the Nickle and Textile Museum artifacts (Sarre and Trenkwald 1926: plate 58).23

19 Several other institutions hold artifacts that can be used for comparative purposes in this object analysis. An artifact at the August Kestner Museum in Hanover has the same main field and border designs as the MAK carpet.24 Other closely related fragments include two artifacts at the Museum of Islamic Art in Berlin: one a corner of the main field and border (No. 1889.150) and another from the main field (No. 1897.58), both of which are similar in fiber composition, knots, and style to the MAK carpet and are assessed as being Turkish from c. 1600.25 We also find one 1575-1625 fragment of the main field at the Art Institute of Chicago (1964.554) assessed as coming from Bursa or Istanbul, one 1575-1600 border fragment at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London (375-1891) similarly assessed in terms of origins, and two carpets slightly smaller than the MAK piece, one of which may be at the de Young Museum in San Francisco, and the other in the V. and L. Benguiat Private Collection of Rare Old Rugs in New York.26 The Benguiat artifact has a different border, which may have been attached later. Pieces used for comparison are typically attributed to the Anatolian region, and to a time period from mid 16th century to early 17th century.

20 Whether the Nickle, Textile Museum, and MAK carpets all come from the same larger textile cannot be conclusively determined. The dates and carpet types given to these similar pieces strengthen a late 16th-century or early 17th-century Ottoman Cairene attribution. Laboratory and structural analysis could be of further use, but data would likely still lead to further speculation. Even cut into smaller pieces—whether because of the original carpet’s poor condition or to sell them in more manageable sizes—these carpets remained desirable to western buyers and have found their way in major museum collections.27

Functional, Cultural and Spiritual Objects

21 A carpet’s functions are many and are dependent on the cultures that produce and use it. Historian of Sasanian and Islamic art Kurt Erdmann, in his classic work Oriental Rugs (1976), hypothesizes that the very first knotted rugs were invented by nomadic shepherds who needed protection against the cold ground but could not afford to simply slaughter their stock to make floor coverings from their hide. They could, on the other hand, make use of the wool by shearing the beasts (1976: 15).

22 The primary use of carpets in Asian and Mediterranean cultures (as it would have been for Ottoman Cairene carpets) was as a floor covering, an important function that is often misunderstood in the Western World. Sitting, eating, sleeping, and praying are all activities that took place on the ground since ancient times and have continued in some regions (Erdmann 1976: 15).28 The multifaceted and widespread use of floor coverings means that an extensive range of designs and weave structures developed in different regions and became markers of social and cultural identity. Many carpets became symbols of status, class, and tribal affiliation. The Nickle fragment is an example of what the most luxurious, highest quality weavings of the late 16th and early 17th centuries would have looked like. Enormous and magnificent rugs furnished palace floors, private quarters of the nobility, and those of major mosques. In a textile culture, they spoke volumes. They conveyed power and entitlement. Several sources tell us that the Ottoman Sultan Murad III (reigned 1574-1595) ordered eleven Egyptian master carpet-weavers as well as their carpet wool to be transported to Istanbul at the end of the 16th century (Boralevi 1987: 26; King and Sylvester 1983: 79; Mackie 1973: 34-35; Ydema 1991: 21). This is a testimony of the high level of skills these weavers had attained that made the Sultan bring them to his capital. Other sources speak of an Ottoman Imperial order for ten large fine carpets to be made in Cairo in the mid 16th century (Thompson 2006: 167). This speaks of the desirability of Egyptian carpets and the value placed on their unique designs and exceptional quality.29 Even cut in smaller pieces later in their history, knowledgeable collectors would recognize their importance.

23 To the Western World, the Near and Middle Eastern rugs they coveted could signify the sacred or divine, material wealth, and secular intellectualism. As the single most expensive import from the East, carpets were rare and only for the very rich, at least up until the late 18th century (Ruvoldt 2006: 654). For European carpet consumers of the Renaissance, these objects, because of the sacred spaces in which they first appeared, could convey the “divinely inspired status” of their sophisticated owners (Ruvoldt 2006: 654). According to art historian Maria Ruvoldt, this could be due to the fact that Oriental carpets were first featured in European paintings of the religious genre, in sacred spaces, particularly in churches, or with sacred figures (2006: 654). Ruvoldt also advances that there was an awareness among Europeans of the original use of some of these carpets as prayer rugs in the East. Even though their use in the West was not associated with the Islamic faith, carpets such as the one we are studying could still mark a space as sacred or privileged (Brown, Humfrey and Lucco 1997: 59-67; Mack 1997: 59-67).

24 By the end of the 18th century, Oriental carpets went out of fashion and were rarely seen in painting or included in records and inventories, until the last quarter of the 19th century when they were back in fashion and again desirable in Western markets (Roth 2004: 25-27; Ydema 1991: 22-23). They started to reappear on the Western scene along with artistic revival movements, such as the Arts and Crafts Movement, and the general vogue for Orientalism that emerged at this time (Roth 2004: 25-27). Anthropologist Brian Spooner described this 19th-century infatuation as “Ruggism” and links it with a disenchantment for modernity (Barnett 1995: 13-14; Spooner 1986: 195-235). As reveries of comfortable, laid-back “Oriental” lifestyles attracted Europeans and Americans during this time, many carpets stored away started to resurface and were sold for extraordinary prices (Roth 2004: 25-28). Older pieces were described as “authentic,” as opposed to the replicas that were now industrially produced in Europe, which is why even a fragment of an authentic carpet may have been seen as valuable by collectors (Roth 2004: 42-43).30

Nineteenth-Century Alterations

25 The late 19th century is when the Ottoman Empire started to weaken, and probably when the Nickle artifact was assembled. As a product of high Ottoman taste and unique technical abilities, it would have retained value, especially in light of the revival of popularity of such textiles in the West. This is a period when court carpets found their way out of Ottoman palaces. Textile expert Angela Völker explains that several artifacts comparable with the Nickle fragment were bought in Istanbul either late in the 19th century or very early in the 20th century (2001: 58). Did the Nickle piece follow this path on its way to the Sotheby auction in London? We can hypothesize about possible scenarios.

26 Again, our findings suggest that the Nickle carpet fragment was likely part of the main border of a larger original carpet comparable to the MAK piece (Fig. 14), and is likely related to other surviving museum pieces. According to Friedrich Sarre’s and Hermann Trenkwald’s 1926-1929 book on Oriental carpets from the MAK, the larger original carpet that the Nickle’s piece came from probably had an inner field design with no regards to the limits of its borders.31 This is the case for the MAK piece. Research by Angela Völker on Oriental pile carpets at the MAK in 2001 indicates that their piece was purchased in 1888 in Istanbul by Arthur von Scala, the museum’s director at the time (2001: 58). Völker also adds that the closely related carpet from the Victoria and Albert Museum in London was also bought in Istanbul in 1891, while the carpets in Berlin were bought there in 1889 (58). Other fragments are silent or vague: the credit line of the carpet at the Textile Museum at George Washington University states that it was acquired by George Hewitt Myers in 1950, although it doesn’t say from where.32 In addition to stylistic matches, the yarn and woven structure of the MAK carpet, the small Victoria and Albert carpet, and the Textile Museum carpet are similar: technical analysis reveals that all three have silk warps and wefts, “S”-spun wool pile, and an asymmetrical Senneh pile knot, typical of the unique structure of Ottoman Cairene carpets.33 While we cannot attest to the presence of silk in the Nickle piece at this point in time, future testing could serve to fully connect this piece to the other three. This slight variation in size may be normal due to changes in the hand-weaving process and handling and environmental conditions. Therefore, it is safe to assume that the Textile Museum and the Nickle artifacts both do originate from the same carpet. 34

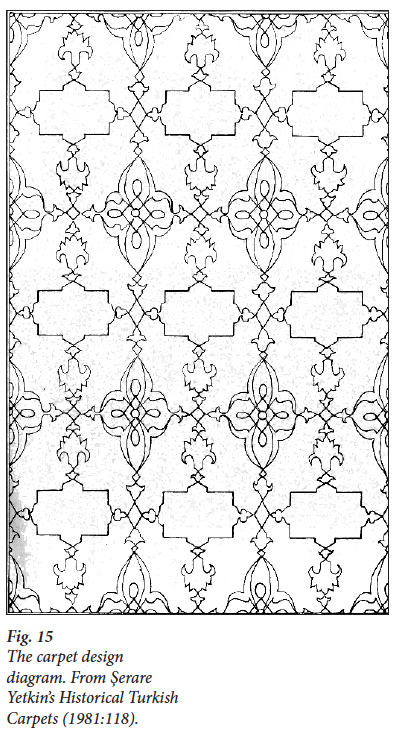

27 Using several existing carpet fragments, such as the Nickle, MAK, and the Textile Museum pieces, to identify and situate parts of the original large “primary” carpet is a worthy exercise made easier to researchers through access to online museum databases. Şerare Yetkin has previously suggested that some of these fragments may have originated from the same carpet. In his 1981 book Historical Turkish Carpets, he includes the carpets at the Islamic Museum in Berlin and the August Kestner Museum based on their design similarities (124). With the advent of online searches, we suggest that the carpet at the Victoria and Albert Museum, as well as those at the de Young Museum and the Chicago Institute for Art, may have all also started their lives from this one primary carpet based on design similarities alone, since technical analyses of these pieces are not readily available. Yetkin only provides a diagram of the complete pattern of the main field of the original large primary carpet. This is nonetheless extremely helpful to determine how all these various carpet pieces may fit together (Fig. 15) (Yetkin 1981: 118). Yetkin triples the size of the MAK main field, which makes sense if we consider the large main fields of the pieces at de Young Museum in San Francisco and the V. and L. Benguiat Private Collection of Rare Old Rugs in New York.

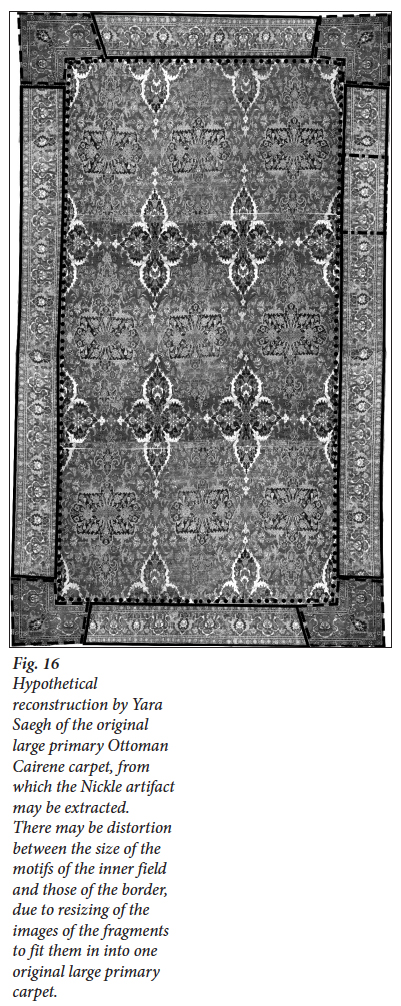

28 As part of this research, we used Yetkin’s reconstruction of the main field for scale and went beyond this scheme to obtain the border, from which the Nickle fragment was likely extracted. We manipulated images of several artifacts in different collections to create an image of what the original large primary carpet may have looked like (Fig. 16). We manupulated and multiplied the MAK artifact to create the inner field (dotted outlines). We did the same for the Textile Museum artifact to create the top, bottom, and side borders (solid outlines). We also copied the fragment at the Museum of Islamic Arts in Berlin for the corners (dashed outlines). The Nickle piece may have been taken from any part of the border (dotdashed outlines for scale). The reason for using the MAK and Textile Museum carpets for this reconstruction is because they have the largest available complete inner field (MAK piece) and border (Textile Museum piece), and their fiber and yarn composition and measurements are available. The Museum of Islamic Arts in Berlin is the only one with readily available pictures of a corner pattern. These three artifacts are thus sufficient to estimate the entire large primary carpet but future studies could use all available artifacts to attempt to find where they may be situated individually.

29 From this scheme, we can obtain the dimensions of what could be the original large primary carpet. We could use the measurements from the different components of the Nickle piece to obtain the dimension of the MAK main field (334 long x 223 cm wide) and, with these measurements, an approximation of the overall dimensions of the large primary carpet may be deducted. Knowing that the Nickle’s border section composed of three registers covers 15.5 cm and that two of these borders totalling 31 cm are found on all four sides of the MAK piece, we must substract 31 cm from 254 cm to obtain the width of the MAK main field, which should be 223 cm. As three MAK carpets fit in the Yetkin plan, we multiply that number by three to obtain the length of the main field of the original large primary carpet, which could thus be 669 cm. The width of the main field of the primary carpet is similar to the length of the MAK artifact’s main field. To obtain this dimension, we can subtract two of the Nickle’s border sections with its three registers, 31 cm, and two of what constitutes the width of the Nickle’s main field, 75 cm, from the overall length of the MAK artifact, 440 cm, for a total of 334 cm. With the measurement of the primary carpet’s main field (669 cm long by 334 cm wide), we must add the width of the entire Nickle carpet on all sides (37.5 cm). As such, the original primary carpet may have measured 744 cm long by 409 cm wide.35 Further research could use these measurements to help compare this piece with others and narrow down the spaces that could accommodate such a monumental rug, which may help find the piece’s provenance.

30 The provenance provided on several fragments that may be linked to this original large primary carpet indicates that it may have been altered before the first known fragment (the MAK piece) left Istanbul in 1888. We may thus speculate that the larger primary carpet was cut up no later than 1888 and likely altered soon before that date with the intent to find multiple buyers, many of them abroad and knowledgeable about the value of the original large primary carpet. Whether this carpet was originally woven in Ottoman court-production centres or in other Ottoman controlled areas is not known. What we do know is that this type of late 16th and early 17th-century Ottoman Cairene carpet in this monumental size was likely extremely expensive and, as such, an Ottoman court commission is highly possible as we know of Sultan Murad III’s appreciation for these textiles. This means that the Nickle artifact may once have been part of an Ottoman Imperial court carpet and thus a witness to a life fantasized about for centuries.

Conclusion

31 This paper examined a late-16th to early-17th-century Ottoman Cairene carpet in the University of Calgary’s Nickle Galleries. The artifact is one of two types of knotted carpets distinctive in their joint use of “S”-spun wool yarn and asymmetrical Senneh knotting. Mamluk carpets are the other types, which are considered predecessors of Ottoman Cairenes. Mamluk carpets have a reduced color palette and geometric designs while Ottoman Cairenes have smoother, more organic, and naturalized foliage and flowers in the “saz style,” present in other contemporary Ottoman arts of the 16th and 17th centuries. Drawing inspiration from Persian and Anatolian styles, Ottoman Cairenes were instantly recognizable hybrids that were highly prized for their aesthetic qualities, craftsmanship, and novelty in the cyclical trends that impacted carpet production.

32 Where the Nickle artifact was actually first produced is debatable. Ottoman Cairenes, just as Mamluk carpets, are typically understood to have been woven in Cairo, Egypt, or in Istanbul or Bursa, Turkey. The undeniable structural similarities between both types makes it possible that they were woven by the same group of people, be they Egyptian or another group of weavers. Evidence indicates that Egyptian weavers and their supplies of wool were transported to Istanbul, Turkey by Sultan Murad III to weave their much sought-after carpets for the Ottoman court. Such extravagance and migratory behaviours adds complexity to the story and should be explored further not only in relation to Ottoman capitals but also throughout the Ottoman Empire and its numerous weaving centres. If Suriano’s hypothesis is correct and Mamluk carpets were in fact a product of Syrian weaving centers, then this may add a layer of complexity to the history of the Nickle piece and all Ottoman Cairene carpets.36 Doubts remain: if Syrian production is a possibility, why would Sultan Murad III order Egyptian weavers to Istanbul? While Suriano’s arguments about Syrian production centres have been to a large extent rejected by scholars, perhaps it is time to explore exchanges in weaving knowledge between Egypt and its neighbors, Syria among them.

33 Based on comparisons with several artifacts in other museum collections, the Nickle piece is most likely a border fragment cut from a larger carpet. Using Yetkin’s 1981 research as a starting point, and adding a current search for other fragments, the main field of the larger primary carpet was mapped out and the measurements of the Nickle artifact was factored in to estimate the size of the original large primary carpet as 744 cm long by 409 cm wide. The sheer size of such a sought-after Ottoman Cairene primary carpet therefore makes it feasible that it was used as a floor covering for large spaces such as palaces or mosques. The original large primary carpet was likely cut in pieces, either because of its deteriorating condition, to fit smaller rooms, to profit from the sales of many more pieces, or, for many of these reasons combined, and sold to a number of collectors. A key point of reference is the work of Angela Völker on a large Ottoman Cairene carpet (with a border similar to the Nickle artifact) in the Austrian Museum of Applied and Contemporary Art (MAK). Völker describes how the MAK piece was purchased by museum director Arthur von Scala in Istanbul in 1888 and how several related pieces also found their way in European museums soon after. From her research, the year 1888 is used as the earliest evidence of the fragmentation of the larger primary carpet and a location for the original carpet in Istanbul.

34 The late 19th century was a period that saw the decline of the Ottoman Empire and a return of interest for traditional Near and Middle Eastern carpets. Popular at a time when Orientalism and the Arts and Crafts movement were on the rise, their earlier history may also speak about the history of taste as they can be seen as products of Ottoman colonialism that favoured motifs and designs popular in other parts of the Empire.37 Studying Ottoman Careines further can help to advance knowledge on the possible migration of skilled weavers throughout the Middle East and the rest of Asia. Sources that address these issues are fewer than those that investigate exchanges between Europe and Asia. Knotted carpets are not the product of isolated weavers, but rather a result of cross-cultural innovation (Barnett 1995: 24-28). What circumstances led to a valuable imperial object such as the Nickle carpet to be sold in pieces might be uncovered through further investigation in Ottoman court archives. Perhaps deeper investigation in Ottoman art and Ottoman palaces might uncover the full story. This is an artifact with an intriguing, albeit somewhat mysterious history, and studying it in more depth might increase understanding of the practical aspects of Ottoman court culture from the 16th century until its collapse in the early 20th century.