Research Reports / Comptes rendus d’expositions

Thimble Cottage and the Country Cottage Tradition in 19th-Century St. John’s, Newfoundland

Introduction

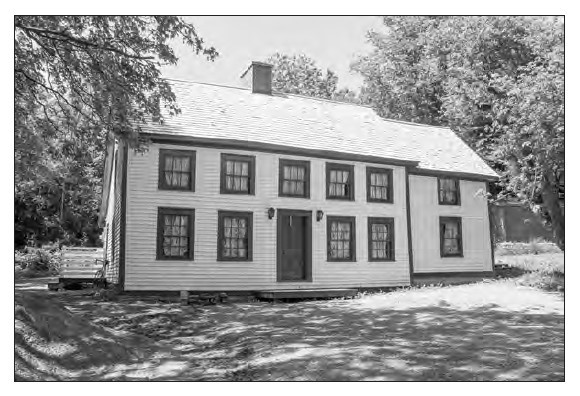

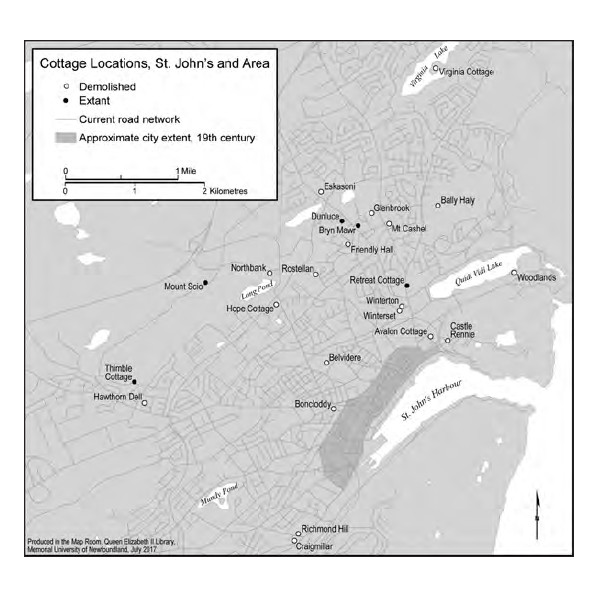

1 Looking out over the city of St. John’s, Thimble Cottage sits on a picturesque hillside property in a corner of Pippy Park (Fig. 1). Built ca. 1850-1855, the property was acquired in 2010 by the Province of Newfoundland and Labrador in an effort to protect its heritage value (O’Brien 1992a: 3; Mannion 2010: 15; CBCL 2012: 1). For most of its history, from ca. 1875 to 2008, Thimble Cottage served as a farmhouse; it was the focal point of the O’Brien family farm. Prior to this, however, the cottage was used as a summertime retreat by Timothy O’Brien, a St. John’s businessman (O’Brien 1992a: 3; O’Brien 1992b: 6).

2 Timothy O’Brien’s retreat was one of many that existed in the countryside surrounding 19thcentury St. John’s. Called cottages, these buildings were large dwellings owned by individuals with the means to afford a second home outside of town. Robert MacKinnon’s study of the St. John’s agricultural periphery has identified at least 52 of these country cottages (1981: 106-109), and other sources suggest that even more may have existed (e.g., Earle 1981: 8; O’Brien 1993: 4, 32; Newfoundland and Labrador Heritage Website (NLHW) 2016).

3 This paper offers an overview of the country cottage tradition in 19th-century St. John’s. Three topics are addressed: the contextual background of “the cottage” as an architectural type; the characteristics of cottages around St. John’s as well as motivations for their construction and use; and the place of Thimble Cottage within this local building tradition.

The Cottage in Architectural Discourse

4 In the British context, the term “cottage” can refer to both vernacular and elite rural dwellings. A cottage can be the modest home of a poor peasant farmer or the architect-designed residence of a wealthy gentleman. The origins of the elite cottage are linked to the ideal of rural retreat. In 18thand 19th-century Britain, a distinct dichotomy existed between rural and urban spaces. Limited wealth meant most people were restricted to just one of these spheres, but individuals of means could enjoy the cosmopolitan bustle of urban life while retaining the ability to escape town for the bucolic peace of the countryside (Archer 2005). This desire for rural retreat is a particularly Anglo-Saxon tradition in the context of modern European history. Its origins have been linked to the enduring political power of the rurally-based peerage in England, as opposed to the centralised monarchies on the continent (Lyall 1988: 19).

5 The elite cottage stemmed from the influence of classical literature. Writers such as Virgil, Pliny, and Horace espoused the virtues of the simple country life of peasants, and the importance of rural retreat for both leisure and intellectual reflection. Though the virtues of simplicity and rural retreat are distinct in the classical texts, they are complementary, and became conflated in the idea of the cottage. Indeed, a cottage is used as the location for rural retreat in Dryden’s 1697 translation of Virgil’s second Pastoral:

O come see our Country Cotts,

and live content with me

(Virgil 1772: 140).

6 By the 18th century, the cottage (or cott) in the form of the vernacular peasant dwelling of the English countryside, came to represent virtuous rural simplicity in contemporary poetry based on classical themes. Importantly, cott in the verse above was translated from the Latin villarum, a word implying a larger, higher-status building like a villa or a farm. Thus, the cottage came to represent not just a simple pastoral ideal, but was also accepted as the material purview of the wealthy. Classical literature was an important marker of cultural capital, and the literary depiction of cottages in classical contexts gave the building a “new, desirable, meaning” removed from grimier vernacular associations, and precipitated its induction into the elite architectural canon by the latter-half of the eighteenth century (Maudlin 2015: 17-25).

7 The conflation of rural retreat with the idea of a virtuous pastoral simplicity created complex architectural meanings for the cottage. Firstly, there was an attempt to design idealised peasant cottages beginning in the latter half of the eighteenth century. These were small, one-tofour-room structures intended as purpose-built homes for farmers or labourers, or garden follies for the grounds of stately homes. Alternately, the cottage concept was appropriated by the wealthy and adapted for rural retreats. Grand designs for substantial country villas were created under the pretence of being cottages. This conceptual flexibility in what was considered a cottage is apparent in the range of large and small designs seen in the cottage pattern books that were published by architects from the late 18th century into the 19th century. For example, Joseph Gandy’s Designs for Cottages, Cottage Farms, and Other Rural Buildings (1805) offers plans and elevations for buildings that vary from a single-room, 8-foot x 14-foot labourer’s cottage, to a 13-room, 2300 square foot “Cottage for a Gentleman Farmer.” Alongside these architect-designed approaches, the simple vernacular cottage of the rural poor endured (Maudlin 2015: 156).

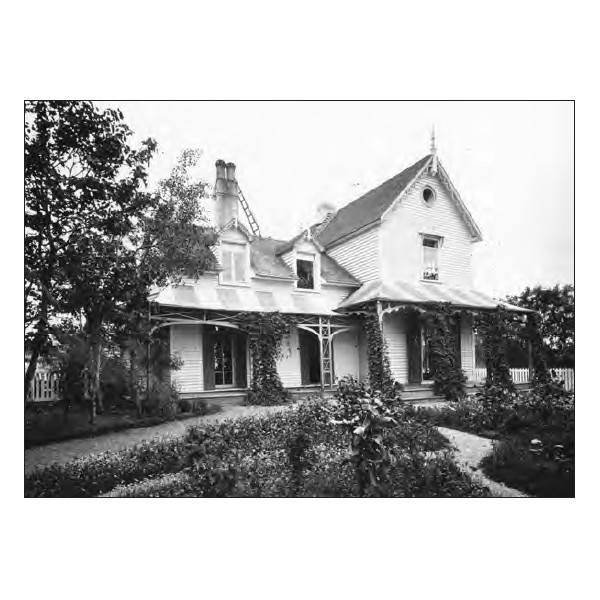

Display large image of Figure 2

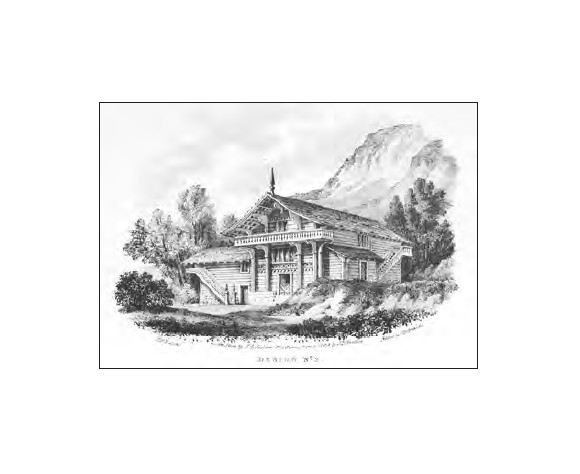

Display large image of Figure 28 Stylistically, architect-designed cottages in Britain evolved from early Neoclassical designs to irregular and ornate Picturesque structures. Cottages in the eighteenth century were designed in the simple and carefully proportioned manner that was typical of the period’s Georgian style. Symmetry was ubiquitous, and designs usually included whitewashed walls and thatched roofs. There was little in the way of decorative detail, though rough-log columns and limited Gothic ornament was sometimes used (Maudlin 2015: 62). However, fashions changed around the beginning of the 19th century as Romanticism began to influence artistic creations, and irregular, picturesque forms came to be favoured in cottage designs. Within the Picturesque movement, various ornamental styles of cottage became popular: Swiss cottages (Fig. 2); Old English cottages, a style that could also include Gothic elements like decorative bargeboards and finials (Fig. 3); Italianate cottages with low-pitched terracotta roofs, eave brackets, arched windows, and square towers; and the Cottage Orné, a thatch-roofed structure with decorative timberwork (Lyall 1988: 33-106). The concept of the cottage had already proven itself flexible in terms of scale, and this flexibility was further extended to encompass a variety of 19th-century styles. Some new cottage styles even appropriated details from royal Tudor buildings or urban merchant houses, belying any idea of the cottage as a simple, rural dwelling (Maudlin 2015: 184).

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3 Display large image of Figure 4

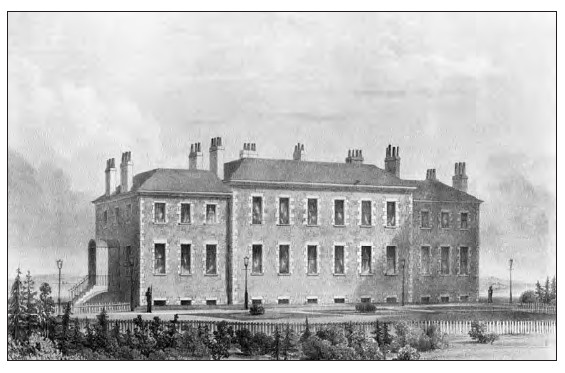

Display large image of Figure 49 As these irregular and ornate styles developed, the architectural cottage came to be understood as the Picturesque alternative to the already-established Georgian villa. Like cottage, “villa” had a flexible meaning. It was often used to denote any type of large, detached, rural house, and there are certainly examples of structures built in a Picturesque style that were referred to as villas (e.g., Loudon 1846: 853-55; Robinson 1836: Plate 43 and 44; Morgan and Sanderson 1860: Plate XIII and XIV). However, during the first half of the 19th century, villas were most frequently understood to be regular, box-like, Georgian structures (Fig. 4), the archetypal country houses prior to the rise of Romanticism. Despite changing fashions, Georgian villas remained a popular elite house type for much of the 19th century, and a number were built around the outskirts of London and Manchester. Though some country “cottages” built by the wealthy were easily as large as these villas, the cottage’s pseudo-vernacular style was strikingly different (Maudlin 2015: 94). A historical awareness of this visual contrast is clearly illustrated by the Regency architect John Papworth in his recommendation that a Picturesque cottage “...should combine properly with surrounding objects, and appear to be native to the spot, and not of those crude rule-and-square excrescences of the environs of London, the illegitimate family of town and country” (1818: 25). The cottage, irrespective of its size, is a structure that diverges from the angular Georgian villa.

The Cottage Around St. John’s

Architectural Characteristics of St. John’s Cottages

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5 Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 6 Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 710 The British architectural context informed buildings across the Atlantic. As a member of the British cultural sphere, Newfoundland inherited notions of rural retreat along with the idea of the cottage as a desirable architectural form. In 19thcentury St. John’s the cottage was mainly thought of as a substantial, stylish, rural, summertime dwelling for the town’s wealthy classes. Cottages were understood as a distinctly elite building type, a departure from the British tradition, where cottages could also be smaller, vernacular rural structures or worker’s houses. Alternately, “the villa” appears not to have made the crossing to St. John’s; local 19th-century newspapers never use the term to describe any dwellings around the town and Government House is the only structure in St. John’s that follows the Georgian style typical of most English villas (Fig. 5). As will be seen, there is a distinct visual contrast between this very large, box-like official residence, and the smaller country houses of the local elite, and this presumably contributed to the universal adoption of the term “cottage” to describe the latter. At the other end of the social spectrum, the worker’s cottage is replaced by the Newfoundland tilt (O’Dea 1982). This local term for a temporary shelter or single-roomed dwelling is derived from the word for an awning over a boat, and reflects Newfoundland’s maritime heritage better than the agricultural cottage (Story, Kirwin, and Widdowson 2006 [1990]: 567-68).

Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 8 Display large image of Figure 9

Display large image of Figure 9 Display large image of Figure 10

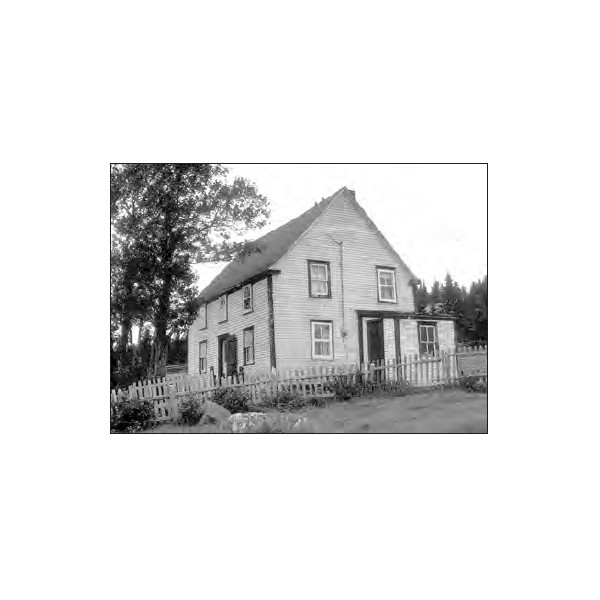

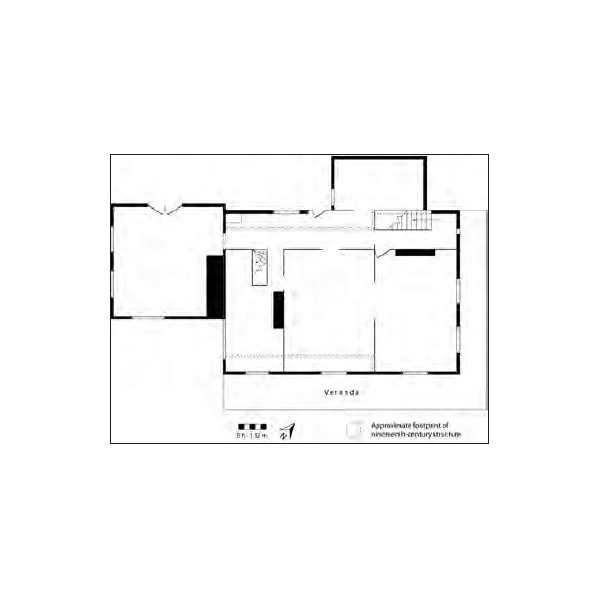

Display large image of Figure 10 Display large image of Figure 11

Display large image of Figure 1111 Though smaller than government house, the cottages around St. John’s were still substantial structures. Nineteenth-century newspaper advertisements describe them as having between eight and thirteen rooms, with the smallest identified still having at least six rooms (Public Ledger, April 19, 1844, September 26, 1845, April 9, 1847, May 25, 1849, April 23, 1850; Royal Gazette, August 1, 1837; Times General and Commercial Gazette, May 10, 1837, July 19, 1842, June 27, 1846, April 21, 1847, October 14, 1848). The term “substantially built” was also used to describe cottages (Public Ledger, May 5, 1863, December 30, 1870). Beyond the cottage itself, further space was provided by outbuildings, including private stables and coach houses for those wealthy enough (Times General and Commercial Gazette, July 19, 1842, June 12, 1847). Information regarding the appearance of cottages around St. John’s is limited to a small number of photographs and extant structures, but these all illustrate the scale of the dwellings. Two of these buildings, Richmond Hill and Mount Cashel, were large mansions (Fig. 6 and Fig. 7). Four others, Dunluce (Fig. 8), Retreat Cottage (Fig. 9), North Bank (Fig. 10), and Mount Scio (Fig. 11) are not on the same scale, but are still sizable houses.

12 These cottages were situated on rural properties that were often cultivated and landscaped. Throughout most of the 19th century, St. John’s proper was confined to the area within Military Road. Beyond were the barrens and a few scattered dwellings, including cottages. A map plotting the known locations of some cottages clearly shows their rural situation.1 Large properties surrounded cottages, and this land was often used for agricultural or horticultural purposes. Newspaper advertisements reference large kitchen gardens, pasture land, and fruit filled trees (Evening Telegram, March 4, 1893; Public Ledger, August 18, 1857, September 12, 1865; Times General and Commercial Gazette, May 10, 1837, July 11, 1838, August 7, 1839, October 25, 1851) and MacKinnon notes multiple cottages with land cleared for cultivation (1981: 106-109). Parts of these properties could also be landscaped for ornamental effect. Hawthorn Dell, a large cottage to the west of St. John’s, is noted as having a grand entrance lane and elaborately landscaped grounds (O’Brien 1993: 3). A gardener’s job description in a 19th-century newspaper advertisement shows what features one might expect to find in a cottage garden: “[Wanted:] A young man who perfectly understands the gardening business, particularly ornamental and rural gardening viz rockwork, hermitages, rustic seats, chairs and tables etc…” (Royal Gazette, June 28, 1831). Other advertisements describe cottages with flower gardens, a tennis court, and ornamental trees (Evening Telegram, May 29, 1882; Public Ledger, August 15, 1885).

Display large image of Figure 12

Display large image of Figure 12 Display large image of Figure 13

Display large image of Figure 1313 Cottage owners were affluent and often prominent members of the St. John’s community. They included doctors (Dr. Samuel Carson), members of the legislature (Hon. A. W. Desbarres, Hon. A. W. Harvey, Hon. James Crowdy, Hon. John Kent), high-ranking public servants (Surveyor General Joseph Noad, Surveyor General George Holbrook, Chief Justice John Bourne), merchants (Kenneth McLea, John Steer, Thomas Brooking), and members of the clergy (Archbishop Michael Howley) (see Lewis and Earle 1974: 250; Earle 1981: 8; MacKinnon 1981: 106-109; Crosbie 1998). For most, the maintenance of a cottage was an expense on top of a house in town (MacKinnon 1981: 44). An 1857 contract between the architect James Southcott and the merchant John Steer notes that Steer’s Hope Cottage was to be built for £420 (unpublished contract in the collection of Shane O’Dea). This was a sizable sum for the time considering that the average export price in 1857 for a hundredweight (50.8 kilograms) of salt cod—the staple of the Newfoundland economy—was only 14s 5d (approximately £0.7) (Ryan 1986: 262). Effectively, Hope Cottage was worth 30.5 tonnes of salt cod.

14 Based on the limited numbers of cottages whose exterior appearance is known, it seems that they were built to be stylish. However, internationally-derived styles were interpreted in local ways. Sometimes a cottage designer’s attempt at style was merely a matter of applying fashionable Classical or Gothic decoration to existing local house forms (Fig. 13). This is the case with Dunluce and Retreat Cottage, where decorative bargeboards, finials, door and window frames, columns, pediments, and verandah trellises were attached to the rectangular, gable-roof houses typical of the area.2 Richmond Hill also follows this traditional form, though the typical peaked roof has been truncated to avoid the immense gable which would have been produced by the building’s substantial size. Other cottages embraced imported architectural styles to a greater degree. The form and decoration of Mount Cashel, North Bank, and Mount Scio were clearly influenced by the Old English style. This inspiration is evident in their projecting bays beneath front-facing gables, ornate bargeboards, finials and verandah brackets, lead-light windows, and Gothic window openings. North Bank and Mount Scio also display a lack of symmetry, another hallmark of the Old English style. Nevertheless, even these overtly style-conscious buildings still appear to have been assembled using familiar forms. Mount Cashel is the combination of three traditional gable-roof house structures in an H-arrangement. Similarly, both North Bank and Mount Scio were created by combining two structures in a T-arrangement to create an irregular, picturesque appearance.

Display large image of Figure 14

Display large image of Figure 14 Display large image of Figure 15

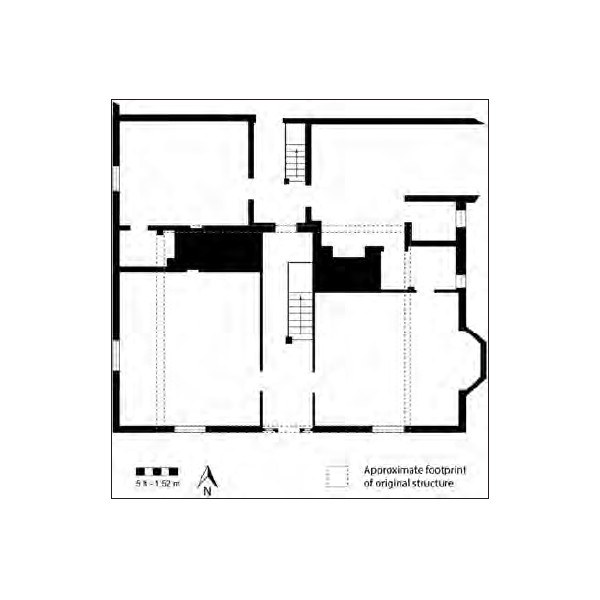

Display large image of Figure 1515 There are very few cottages around St. John’s whose internal layout is known. Aside from Thimble Cottage, only the floor plans of Mount Scio and Retreat Cottage are available: the former has a side-hall plan (Fig. 14) and the latter has a central-hall plan (Fig. 15). Additionally, Richmond Hill is known to have had a central-hall plan, and the paired chimneys and central door of Dunluce also suggest a central hall. Historic images of Mount Cashel and North Bank do not indicate clearly a particular internal layout. It is impossible to identify any clear patterns in the internal layout of St. John’s cottages based on this small sample. However, there does at the very least appear to be a superficial preference for centre-hall plans in the cottages that are based on existing local forms (as opposed to the Old English-style cottages).

Uses of the Cottages

16 Many of these cottages were used as summer residences, though at least some were occupied as permanent dwellings. As already noted, most cottages were owned in addition to houses downtown. For example, the Brookings, a merchant family, had a home on Lower Path (Water Street) as well as Avalon Cottage on the road to Quidi Vidi (Earle 1981: 8). Another family, the Carters, had a property on Monkstown Road, and later Rennies Mill Road, in addition to their Mount Scio cottage on Mt. Scio Road (Jack 2010: 1-2). A newspaper advertisement announcing “A Summer Residence to be let” also implies a tradition of rural retreat during the summertime (Newfoundlander, May 21, 1878). The use of summer cottages appears to endure into the 20th century, and even to this day. Dunluce and Glenbrook Cottage were used as summer homes until the mid-20th century (Jacqueline Ryan, pers. comm.; NLHW 2016), and Mount Scio is still used by the Carter family in the summer (Jack 2010: 2). However, there are also instances of cottages being used as full-time residences. A series of newspaper advertisements for Retreat Cottage suggest that by the late 1830s its occupant, Cristopher Ayre (the governor’s secretary), was living there year-round (Royal Gazette, January 17, 1837; February 13, 1838). This is unsurprising considering that Retreat Cottage is relatively close to town compared to some of the more remote cottages around St. John’s, and it is even closer to Ayre’s workplace at Government House. Another newspaper advertisement records the architect and builder William Haddon selling his house downtown and moving to his “Cottage on the Barrens” (Times General and Commercial Gazette, July 3, 1839).

Motivations for Cottage Construction

17 Why were town residents building or buying these expensive rural cottages? A major factor must have been the desire to escape the more unsavoury aspects of 19th-century St. John’s. A report from 1818 paints a vivid picture:

18 The “filth” in question was likely a combination of animal manure, human waste, and fish offal. Court records suggest the presence of stray dogs and livestock, as well as whole herds of cattle driven though the town (Pocius 2014: 14). Horses would have been the main beasts of burden, and they would have added to the excrement undoubtedly produced by the other animals. Prior to 1851, humans contributed to the morass in the form of open sewers that carried excrement and all manner of rubbish down the hillside to the harbour-front (Baker 1983: 28). During the summer months, the cod fishery also made St. John’s “the fishiest of modern capitals” (Warburton and Warburton 1846: 11). A complaint about the situation noted “the disgusting and offensive way in which fish is suffered to lay about the streets, the heads and entrails thrown in every direction” (Pocius 2014: 14). It is no surprise that those who could afford it would choose to occasionally escape the town’s filth to a rural cottage.

19 Foul smells and health risks accompanied this filth. The open sewers would have exuded a formidable stench in the summer months, and this would have merely added to the ubiquitous smell of cod. Sir Joseph Banks refers to this latter point during a visit to St. John’s in the 1700s: “As everything here smells of fish so you cannot get anything that does not taste of it” (Lysaght 1971: 147). Aside from being generally unpleasant, the odours of downtown would have been perceived as a danger to the health of St. John’s 19th-century residents. Miasma theory was in vogue, and noxious emanations (“bad air”) from decaying matter were thought to cause disease. Though we now know that this is not true, the decaying materials associated with the noxious smells were indeed harbingers of disease, and the shortcomings of the town’s poor sanitation were made dramatically apparent with the outbreak of cholera in 1854 (Baker 1983: 28). Getting out of the town during the summer, when the smells (and bacteria) would have been most virulent, was a way of avoiding disease.

20 Fire was the other major risk in the town. Most buildings were constructed of wood, and the alignment of Water Street with the prevailing south-westerly summer wind meant that any blaze had the potential to do massive destruction. It is no surprise then that the city saw at least 22 major fires over the course of the 19th century. Three of these were “Great Fires” that consumed most of the city (O’Neill 1976: 597-648). A cottage in the countryside was a haven away from this urban threat: it could act as a retreat if one’s town house was burned, and it could also be used to store and display expensive furnishings without fear of their destruction by fire.

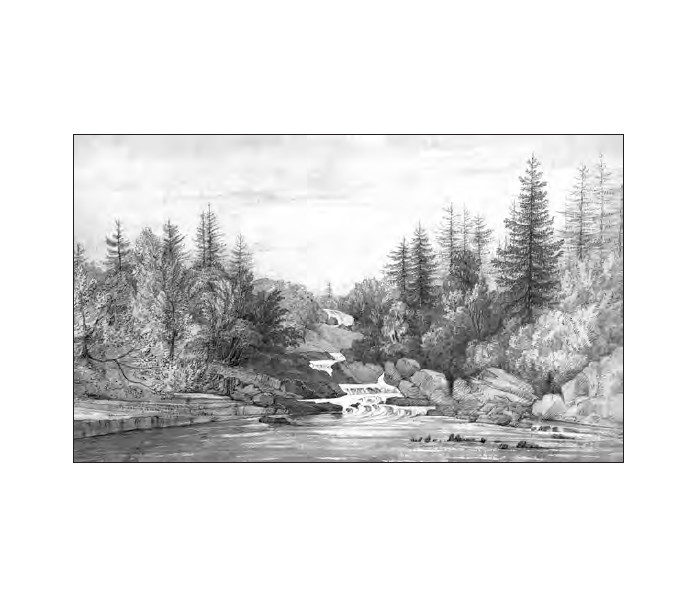

Display large image of Figure 16

Display large image of Figure 1621 Beyond these pragmatic concerns with the perils of downtown life, there were cultural factors that persuaded the wealthy residents of St. John’s to appreciate the countryside and the idea of a rural dwelling. As noted previously, rural retreat was seen as an antidote to the drawbacks of urban life since at least the beginning of the eighteenth century. The arrival of the Romantic Movement at the end of the century saw the apotheosis of the countryside as the realm of calm, beauty, and inspiration (Pocius 2014: 8). This ideal continued into the 19th century and the cottage acted as its architectural manifestation. A romantic attitude towards the rural landscape around St. John’s can be found in both visual representations, such as the 1831 Oldfield-Wyatt sketches (Fig. 16), as well as literary description:

22 In this description, rural architecture is incorporated into the romantic landscape. Even the sentimental, bucolic names given to many of the cottages around St. John’s emphasise their role as elements of an idealised rural landscape: Ashleaf, Belle Vue, Hillsview, Paradise Cottage, Riverside, Rose Cottage, Sunnyside, Woodlands. By investing in a rural cottage, St. John’s wealthiest residents were participating in the cultural traditions of their time and partaking in the virtue that nature was thought to offer.

23 The rural cottage was also a status symbol. In Britain, a country retreat was typically associated with the gentry: “since the sixteenth century, the traditional British way of climbing the social ladder was for a successful businessman or merchant to buy a country estate and insinuate his family among the landowning society” (Lyall 1988: 19; see also Maudlin 2015: 19). Because it was expensive to keep dwellings in both the town and countryside the country cottage was not just a pleasant and virtuous space, but also a mark of status and wealth. As Pocius notes: “The emerging mercantile gentry of Newfoundland often turned to the cottage as an architectural type as a way in which they could emulate a proper privileged landscape” (2014: 9). In St. John’s, this association of cottages with the status of land ownership is most obvious in newspaper advertisements announcing rural land for sale suitable to “Genteel Cottages” (Royal Gazette, July 2, 1833), or cottage interiors that were suitable for a “gentleman and his family” (MacKinnon 1981: 42).

24 The design of cottages also suggests they were status symbols. Their stylishness and significant size set them physically apart from, and symbolically superior to, more common buildings. As noted above, some attempts at style were limited to the cosmetic addition of ornamental features to traditional forms. Other cottages drew on international architectural fashions to create very distinct buildings. Modern designs could be brought to St. John’s in popular architectural pattern books like Downing’s (1851) Architecture of Country Houses, or Loudon’s (1846) Encyclopaedia of Cottage, Farm, and Villa Architecture and Furniture. These designs were then adapted by builders and architects to create distinct houses like the Old English style Mt. Scio, Mt. Cashel, and North Bank. Each of these buildings dripped with Gothic ornament and contrasted with the traditional, unadorned dwellings that most people occupied.

25 A final motivation for owning a country cottage was the opportunity it presented for farming. Many cottages were associated with cultivated land and these “cottage farms” produced a wide range of produce: marrow, cucumber, sprouts, French beans, radish, spinach, celery, cauliflower, lettuce, mustard, thyme, sage, savoury, red cabbage, parsley, and onion. Sometimes hay was also produced for sale, and there were rare cases of commercial dairying (MacKinnon 1981: 44). Farming the grounds of a cottage gave the owner access to a wide variety of fresh produce that was expensive to purchase, if even available. It also provided an opportunity for additional income through the selling of cash crops or surplus produce.

Thimble Cottage

26 Thimble Cottage was used as the summer residence of Timothy O’Brien (O’Brien 1992a: 3; O’Brien 1992b: 6). Timothy was the eldest son of John and Mary O’Brien, both farmers and Irish immigrants. Around 1818, John had begun farming in the Freshwater Valley, an agricultural area to the west of downtown St. John’s (Mannion 2010: 4, 10-11; Mannion and Mannion 2015). Timothy was born in 1824, and lived out the first years of his life in John and Mary’s tilt in the woods; this small makeshift building served as the O’Brien’s home until the construction of a more substantial farmhouse at some point before 1833 (Mannion 2010: 14-15; Mannion and Mannion 2015). Sometime in the early 1850s, Timothy moved from the family farm and established a farm, shop, and carting business alongside Freshwater Road (O’Brien 1992b: 6).3 This was the main artery between St. John’s and the Freshwater valley’s farms, and Timothy’s business could capture the trade of friends and neighbours en route between the two localities (Mannion 2010: 11). He seems to have been successful as a businessman, and when he died in 1903 he was worth an estimated $9000, a substantial amount of money for the time(Newfoundland Will Books 7/249).

27 Though Timothy used Thimble Cottage as a rural retreat, it is unclear if this was its original use. Built ca. 1850-1855, it is possible that the dwelling was erected as the new farmhouse for the O’Brien farm, and was initially occupied by John O’Brien until his death in 1858. The building subsequently passed to Timothy who began to use it as a cottage.4 However, it is suggested in the O’Brien family’s oral history that the building was actually constructed as Timothy’s summer house. Later, after ca. 1875, the structure began to be permanently occupied by Timothy’s younger brother Michael and his family. They worked the surrounding farm, though Timothy retained ownership of the land and buildings (O’Brien 1992a: 3; 1992b: 6-11; 1995: 31).5

Display large image of Figure 17

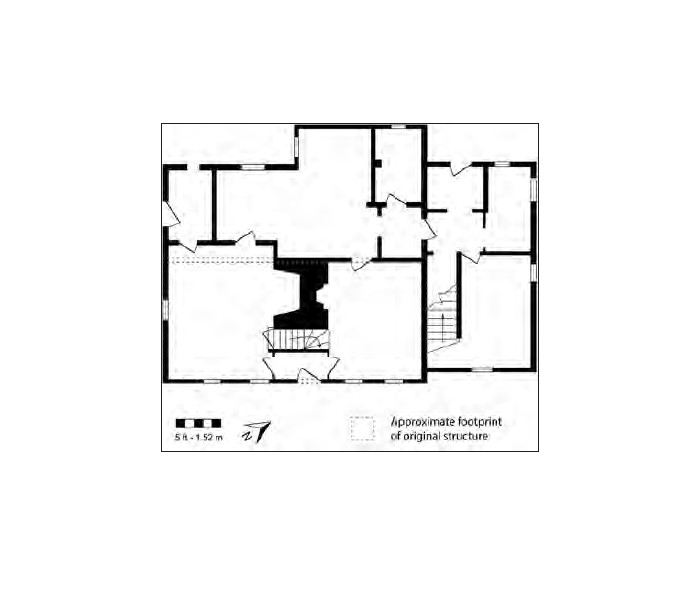

Display large image of Figure 17 Display large image of Figure 18

Display large image of Figure 1828 It seems more likely that Thimble Cottage was originally intended as a farmhouse. Its design has more in common with local vernacular farm buildings than the other cottages around St. John’s. The structure is small—its original form without the linhay had only four rooms, two upstairs and two downstairs—and its austere exterior does not show a concern for stylishness like the cottages discussed above. Thimble Cottage also has a lobby-entry, central-chimney plan that was common in the area, as opposed to the hallway-based plans of other cottages (Fig. 17 and Fig. 18). Furthermore, Patrick O’Brien, another brother who took up farming, built an “architecturally identical home on his lot to the west of his father’s farm” (Mannion 2010: 16).6 Finally, it seems implausable that John O’Brien would let this new house on the family farm just sit empty for much of the year, only to be used by Timothy in the summer. It is more probable that John built the new house in an attempt to accommodate a growing number of grandchildren; prior to moving into Thimble Cottage ca. 1875, John’s son Michael and his wife still lived in the older, four-room, pre-1833 farmhouse along witH their ten children (O’Brien 1992a: 10; Mannion 2010: 15).

Display large image of Figure 19

Display large image of Figure 19 Display large image of Figure 20

Display large image of Figure 2029 However, if we accept the idea that Thimble Cottage was built specifically for Timothy then its design takes on a new meaning. It suggests that Timothy had a more parochial outlook than other cottage owners. Despite his financial success, he had been raised by Irish-Catholic peasants in the rural periphery of a small town. His social situation was likely quite removed from the wealthy, educated, and largely Protestant individuals who consumed international fashions and constructed expensive, stylish cottages around St. John’s. Instead, Timothy’s community was comprised of Irish farmers in the Freshwater Valley: these were his customers, his friends, and his family (Mannion 2010: 11). Within this community, Thimble Cottage was both familiar and modern. It’s lobby-entrance and central fireplace flanked by two rooms is reminiscent of the early Irish farmhouses in the area, including John O’Brien’s (Mannion 1974: 151-52; Mannion 2010: 15) (see Fig. 19). The imposing two-story facade, however, was a more modern feature, a recent evolution of the local vernacular. The change in design, likely influenced by New England housing, had become popular locally around the mid-19th century, about the same time that Thimble Cottage was built (Pocius 1982: 230) (see Fig. 20). As such, Thimble Cottage can be understood as a modern dwelling, distinct from the earlier farmhouses around it, but restrained enough for Timothy’s locally-informed taste (see Hubka 1979: 27).

30 Whatever Thimble Cottage’s origins, the important point is that Timothy adopted it as a summer residence. Buoyed by a successful business, Timothy’s cottage was a material statement of his ascension to middle-class life after humble beginnings in a woodland tilt. Though the building’s design was different than other cottages around St. John’s, its function as a status symbol remained the same. Considering Timothy’s primary residence on Freshwater Road was already sited on the periphery of St. John’s— well away from the worst aspects of downtown, and already endowed with a farm—Thimble Cottage represents Timothy’s participation in the elite tradition of rural retreat as opposed to a pragmatic desire to produce crops or escape filth and fire.7 Even the naming of the cottage clearly aligns it with the other cottages around the town: “Thimble” references bellflowers (campanula sp.) and evokes the romantic idyll valued by the wealthy. Through his use of Thimble Cottage, Timothy O’Brien tapped into a well-established tradition to announce to those around him that he had become a respectable, successful gentleman of means.

Conclusion

31 The idea of the cottage as a desirable architectural type in Britain comes from a historical tradition of rural retreat combined with the pastoral ideal that emerged from readings and translations of classical texts in the 18th century. Over time “the cottage” proved to be a flexible concept that encompassed a wide variety of forms and styles: the vernacular structures of the rural poor; architecturally designed labourers’ cottages and garden follies; large rural mansions for the elite; austere, Georgian styled structures; irregular, picturesque dwellings; as well as a host of ornate 19th-century styles like Cottage Orné, Old English, Swiss, and Italianate.

32 In 19th-century St. John’s, cottages were dwellings for the elite. They were substantial structures, situated on large, cultivated, and landscaped properties outside the town; their architectural designs were intended to be stylish, and their owners were wealthy and prominent individuals. Many who owned cottages only used them during the summer, but some cottages were also occupied year-round. Those who built and bought cottages did so for a number of reasons. Firstly, there was a desire to escape filth, disease, and fire risk downtown. Secondly, cottages allowed one to demonstrate superior social status through architecture and participation in the tradition of having a rural retreat. Finally, the rural setting of cottages provided an opportunity to cultivate produce for consumption or sale.

33 This cottage tradition around St. John’s was the context in which Timothy O’Brien established Thimble Cottage as his summer retreat. However, Thimble Cottage was smaller and less stylish than other cottages around the town. There are two possible reasons for this. One possibility is that Thimble Cottage was built as a farm house for Timothy’s father, John O’Brien, and only later used as a cottage following John’s death. Another possibility is that Thimble Cottage was originally built as a rural retreat for Timothy, but its architecture reflects his locally-informed taste. Either way, Timothy’s use of Thimble Cottage as a rural retreat is a statement of his ascension to the respectable middle class in the wake of his business success.

I am indebted to several individuals and institutions whose knowledge, skills, and assistance made this research report possible: Gerald Pocius, Shane O’Dea, John and Maura Mannion, Michael Philpott (Heritage Foundation of Newfoundland and Labrador), Alanna Wicks (City of St John’s Archives), David Mercer (Memorial University Map Room), and Memorial University Archives and Special Collections.