Research Reports / Comptes rendus d’expositions

Transnational Identities of Early 20th-Century Chinese Immigrants: A Study of Chinese Graves in the General Protestant Cemetery in St. John’s, Newfoundland

Introduction

1 Graves remind people of who existed before them. As Hannah Arendt notes, “The whole factual world of human affairs depends for its reality and its continued existence, first, upon the presence of others who have seen and will remember, and second, on the transformation of the intangible into the tangibility of things” (1998: 95). In St. John’s, Newfoundland, headstones offer some of the most tangible evidence of the city’s immigrant Chinese community in the early twentieth century.

Display large image of Figure 1

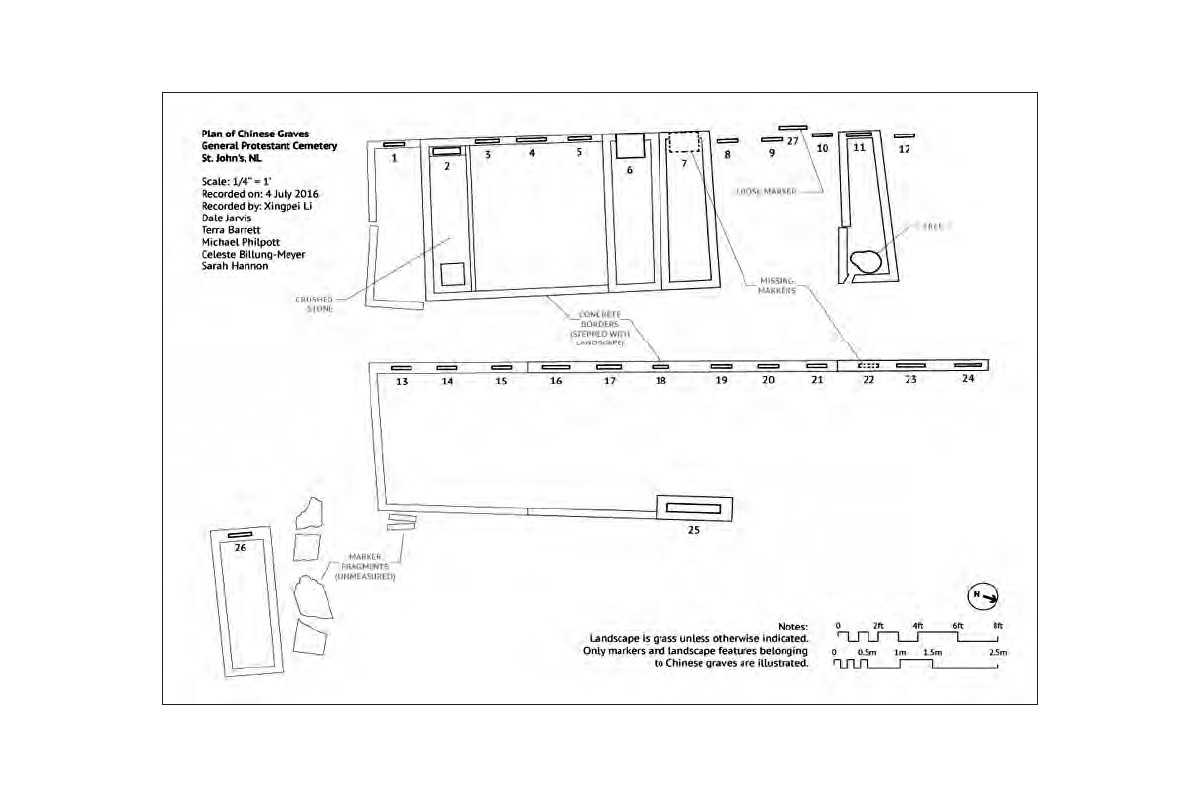

Display large image of Figure 12 In the summer of 2016, I was a member of a research group within the Heritage Foundation of Newfoundland and Labrador that conducted a survey of Chinese graves in the General Protestant Cemetery in St. John’s. We measured the graves and markers, mapped their locations (Fig. 1), assigned numbers to each plot, identified the inscriptions, and documented biographical information from the headstones (see inventory at the end of this report). To further verify the biographical information, we also consulted burial records located in the cemetery archive.

3 There are twenty-five Chinese graves situated in one section of the General Protestant Cemetery. They mark the burial sites of early Chinese immigrants1 who came to St. John’s to make a living, mostly by doing laundry, and who eventually died and were buried in a strange land far away from their birthplace. Drawing on the survey of the Chinese graves, as well as on relevant documentary sources, this article\ examines the headstones for what they reveal about the formation of a complex transnational identity among early Chinese immigrants to St. John’s, Newfoundland.

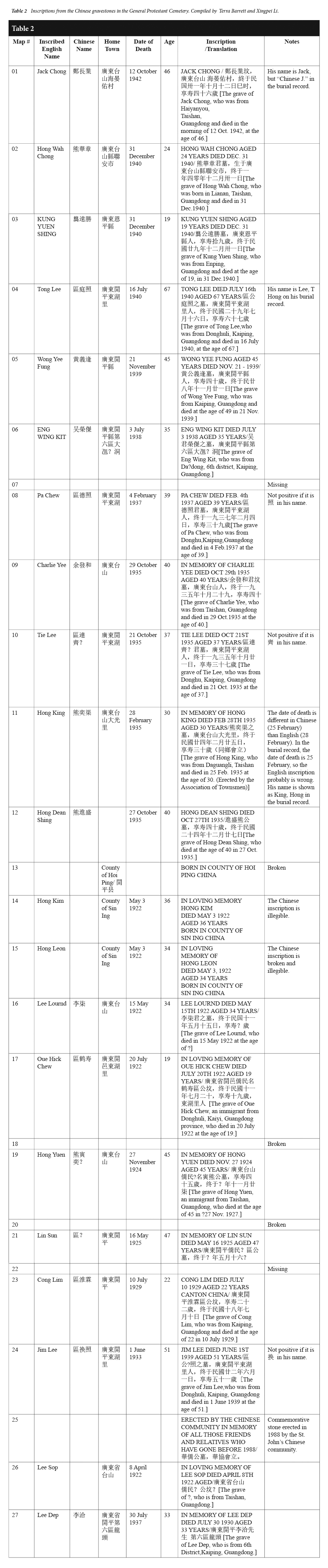

Chinese Headstones in St. John’s

4 The General Protestant Cemetery in St. John’s is owned and managed by the United Church of Canada. Although the cemetery is primarily used for Protestants, it also includes those of other faiths. Entering the cemetery through the main entrance on Old Topsail Road, and walking to the east then turning south for a few meters, one reaches a small section of the cemetery that contains graves marked by headstones with Chinese inscriptions.

Display large image of Figure 2

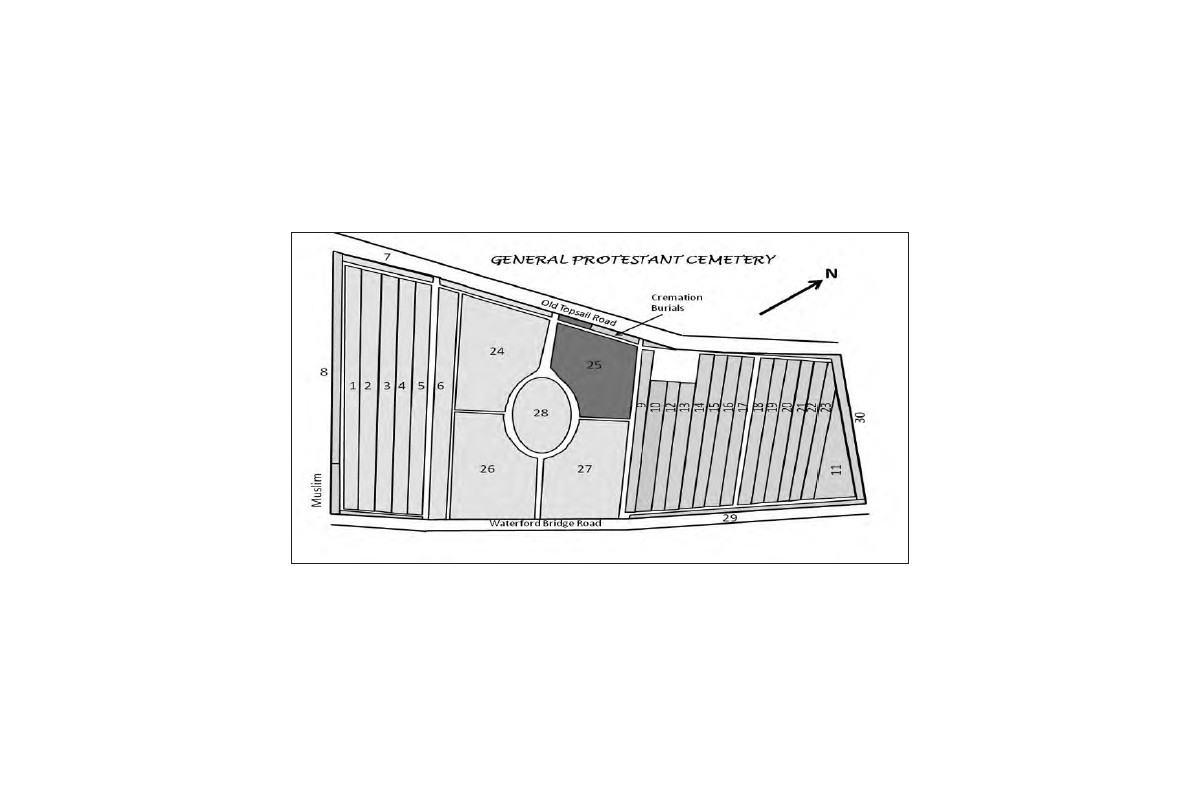

Display large image of Figure 25 According to a diagram of the General Protestant Cemetery, which is divided into different sections, the twenty-five Chinese graves are situated in Section 22 and 23 (Fig. 2). Each section has twelve Chinese graves, while Section 23 also contains a memorial erected by the Chinese Association of Newfoundland and Labrador (CANL) in 1988 in memory of all the Chinese buried there.

Display large image of Figure 3

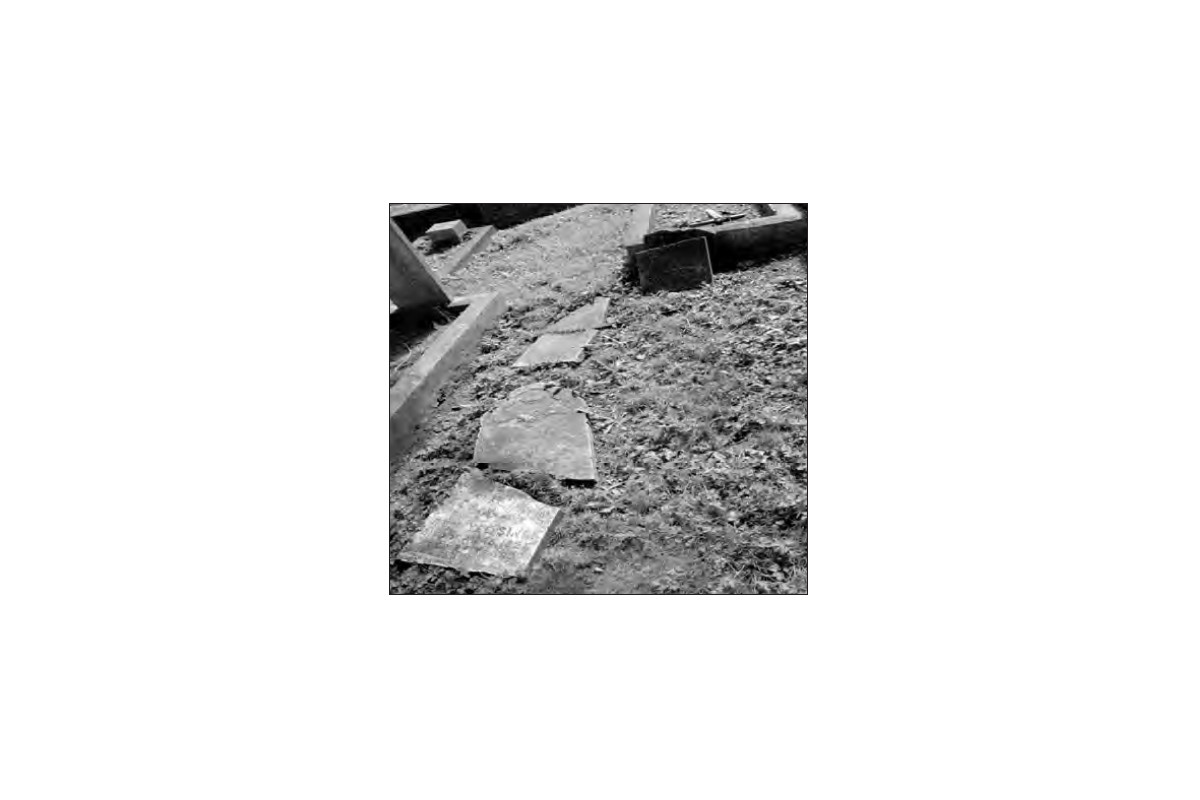

Display large image of Figure 36 The condition of the headstones varies widely. Markers 7 and 22 are missing and there are five makers (15, 16, 13, 18 and 20) broken off from or near the base. The fragments of marker 15 and 16 lie over the respective graves, while no pieces of broken makers 13, 18 and 20 remain on their graves. However, we noted that several fragments of headstone were placed next to grave 26 in the bottom left corner (Fig. 3).

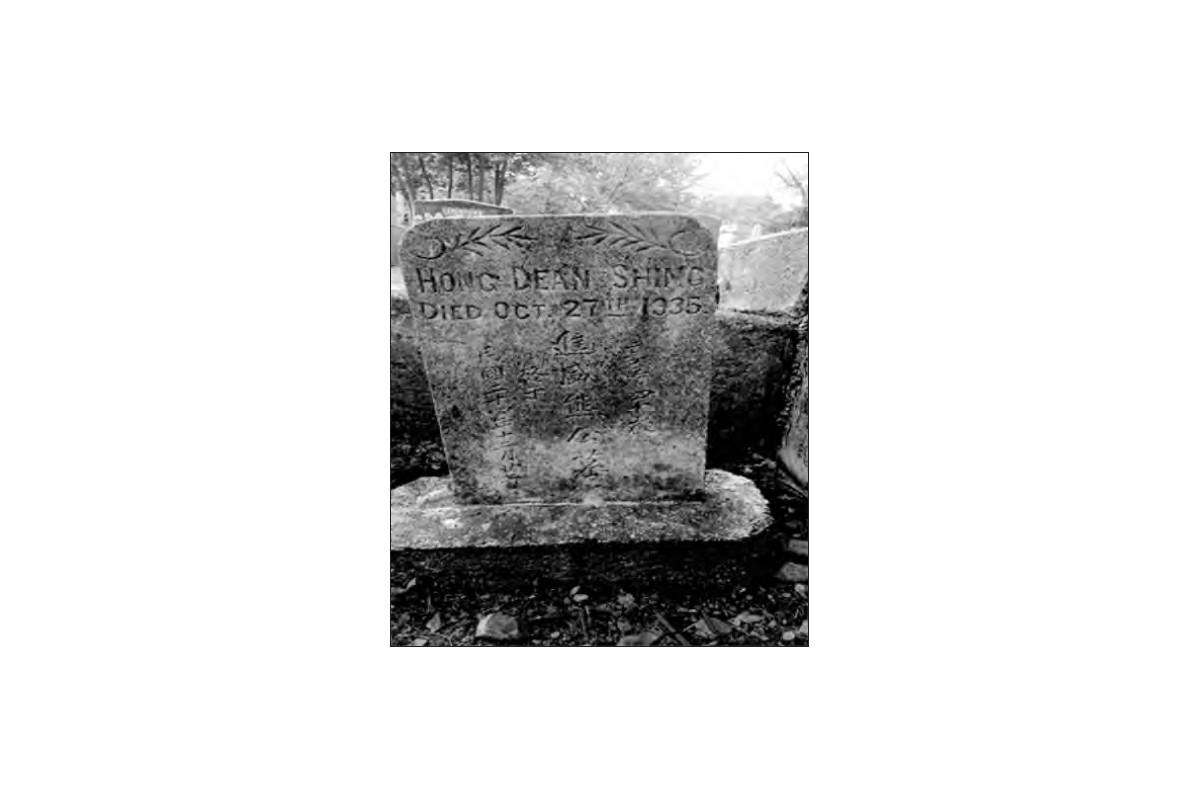

7 A few inscriptions on the headstones are legible (see Fig. 4, 5, and 6 for example), while some are difficult or even impossible to identify completely. From the twenty-three dates of death we were able to collect, we determined that the basic sequence of the burials runs from grave 26 (April 2, 1922) to grave 1 (October 12, 1942). With this order in mind, the original locations of the fragments in the bottom left-hand side can be surmised. The fragment with the date of death of August 14, 1922 probably belongs to grave 18, and the other fragment with the date of May 15, 1929 was likely originally on grave 22. In the same way, we inferred that marker 27 should be on grave 7. The fragment of stone without a date bears the name of the deceased, Gong Kee. Since there is only one unmarked plot left, it is very probable that it is from grave 13. Therefore, although the information available for each headstone varies, we have been able to identify all twenty-five graves and their respective headstones. Building on the premise that mortuary studies can provide glimpses into the minds of past peoples (see Rouse 2005: 82), I argue that these headstones can help trace stories of the early Chinese community of St. John’s and reflect the formation of Chinese immigrants’ transnational identity.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4Early Chinese Immigrants in St. John’s

8 Compared to other areas in North America where Chinese immigrants were attracted by job opportunities around the gold rush and railway construction in the mid-19th century, Newfoundland did not have a Chinese presence until the late 19th century. When Chinese immigrants moved to St. John’s after the 1890s, the city was almost exclusively Caucasian. Baker notes, “by the 1880s St. John’s was a compact, homogeneous community of approximately 30,000 people mainly of English and Irish origin” (1994: 30). One of the first known Chinese immigrants was Choy Fong who arrived in St. John’s in 1894 to open a laundry (Smallwood and Dinn 1984: 272). Following this, more Chinese immigrated to Newfoundland. Like their fellow countrymen across North America, the majority of Chinese immigrants in St. John’s were involved in the hand laundry business. As Mu Li explains,

9 There were eight Chinese laundries in St. John’s in 1913 and this number increased to over twenty by the 1930s and 1940s (Li 2014: 52; Thomson and Button, 1932: 429). As Sparrow writes, “the Chinese in St. John’s became synonymous with the hand laundry business in the early 20th century” (2010: 334).

10 The early Chinese community was comprised of males, many of whom were related. It constituted a “bachelor society,” no matter whether the men were legally married or single. Peter Li writes that before the end of the Second World War, “conjugal family life among Chinese-Canadians was rare, and the Chinese community consisted predominately of married bachelors who sent remittances to support their families in China” (1998: 78). Before Confederation with Canada in 1949, there may have been only one Chinese woman who lived in Newfoundland (Li 2014: 59). Mu Li also notes that “all the Chinese were linked by kinship or region” (2014: 50). The main reason behind this interconnectedness was the immigration mode; Chinese immigrants usually sponsored or brought relatives or countrymen to the host country through what is known as “chain immigration.” Wickberg et al. report that:

11 During this process, wives or other female family members immigrated much later or not at all, since they had to stay at home to care for families. At the same time, most jobs overseas available to Chinese persons, such as gold mining, railway construction, and hand laundry, demanded heavy physical labour that was open only to males. Further, many early Chinese immigrants preferred returning to China after they made a profit. On top of this, anti-Chinese immigration acts were issued in North America that made it very hard for family reunions to take place overseas. Canada increased the Head Tax to $500 in 1903, which deterred many Chinese from bringing their wives or other family members. As Peter Li notes, “Most Chinese probably had difficulty raising the money for their own entry, let alone family members” (1998: 64). Following Canada, Newfoundland introduced a Chinese exclusion act in 1906 which charged a Head Tax of $300 per Chinese and imposed other restrictions. Immigration mode and restrictions, then, meant that almost all the Chinese in early 20th century St. John’s were male and from the same region in southern China.

12 Chinese residents in St. John’s experienced discrimination and racism in all aspects of their lives. They, as well as their laundries, were often targets of physical violence as the following examples from period newspapers demonstrate. A brief report from the February 26, 1906 Evening Herald notes,

13 >Another article from the same paper on June 8, 1908 describes how Kim Lee (his full name was Au, Kim Lee) was tormented by a drunk, who then broke the glass in the door with his fist before he ran away. The reporter also mentioned that “These Chinamen are often tormented by boys and others.” Things were no better in 1912 when an account of a more serious incident was published:

14 Finally, a report published in the Evening Herald on January 29, 1912 indicates that Kim Lee was again assaulted and “received a black eye.” The assailant then went to the store of Hop Wah, on Casey Street, and beat two other Chinese men.

15 Besides physical attacks, Chinese businesses were broken into and robbed. In August 1907, Jim Lee’s watch and some cash was stolen by a nine-year-old school boy in his laundry (Evening Telegram, August 21, 1907). One year later, Jim Lee was severely beaten by two young men who also stole money from his till (Evening Chronicle, December 26, 1908). The March 13, 1909 issue of the Evening Chronicle reported that a woman with her thirteen-year-old accomplice stole money from two Chinese laundries. Local residents also complained about the Chinese laundries in their neighborhoods because of the potential health and safety hazards. One resident went to Fong Lee’s laundry on Prescott Street demanding that the place be demolished, and he apparently assaulted a Chinese employee before departing (Evening Chronicle, September 17, 1908).

16 Racial conflict between local residents and Chinese immigrants continued throughout the first few decades of the 20th century. Between 1911 and 1945, the population of St. John’s increased from 32,242 to 44,603 (Baker 1994: 33). With the rapid growth of its population, the city experienced social problems such as high levels of unemployment that eventually lead to a riot at the Colonial Building in April of 1932 (Baker 1994: 32). High levels of unemployment created tensions between members of the Chinese community and those in the larger mainstream population who worried that the Chinese immigrants were taking their jobs.

17 Owing to the discrimination indicated above, members of the Chinese community found it hard to fit into the city. As indicated above, the Chinese graves in the General Protestant Cemetery are located in one area and are separated from other graves. It is likely that the separation of Chinese residents from others buried in this cemetery stems from, and consolidates, the social isolation early Chinese immigrants experienced during their lifetimes. Due to a restrictive immigration policy and expressions of racism that included assaults and robberies, Chinese immigrants in St. John’s struggled even in death to make their place in a new city and country far away from their homeland.

18 However, it is necessary to note that although its members experienced racism and discrimination, the Chinese community was not a completely isolated group. Some individuals were actively engaged in local affairs. For instance, Kim Lee was one of the leaders of the Chinese community in St. John’s and his name often appears in newspapers alongside some of the other Chinese individuals buried in the General Protestant Cemetery. Kim Lee was popular in the wider community and some newspaper reports reflect an interest in his personal life—his travel between China and St. John’s was noted—as well as concern for his family including his father’s illness (Evening Chronicle, February 25, 1908; Evening Chronicle, September 10, 1909; Evening Chronicle, September 2, 1911). One of the reasons for this increased interest in Lee as an individual might be his personality. In spite of being Chinese, he was also very keen to integrate into the host community. For example, he apparently attempted to coordinate the trade of cod fish between Newfoundland and China and one newspaper reported that “Mr. Kim Lee ... is sending samples of our dried codfish to China, and he thinks that he will have no difficulty in opening up a trade in the article” (Trade Review, March 20, 1919). His activities suggest that Chinese immigrants were trying to contribute to their host community of St. John’s, and his entrepreneurial efforts reflect that throughout North America Chinese immigrants were progressively adapting themselves to their host culture. During the difficult and complex process of adaptation, Chinese immigrants in St. John’s consolidated their own Chinese identity and eventually forged a new transnational identity.

Transnationalism and Identity

19 Several theories help illuminate aspects of immigrant identity. Classical assimilation theory assumes that immigrants want, and gradually are, able to meld completely into their host country. On the other hand, multiculturalism or pluralism asserts that immigrants retain their cultural differences from their home country as a form of agency (Kraus-Friedberg 2008: 124). While useful, both models have been criticized for their failure to address certain dynamics that immigrants experience. For example, assimilationists underrate the value of immigrants’ own traditions to their host country while multiculturalists fail to explain the inequalities that persist in ethnic groups (Kraus-Friedberg 2008: 124). Transnationalism offers a more nuanced alternative. Researchers who approach immigrant identity from this perspective tend to believe that the formation of immigrants’ identity derives from many sources, and “immigrant’s involvement in both their home and host societies is a central element of transnationalism” (Smits 2008: 112). As a result, immigrants “create new cultural products and exercise multiple political and civic memberships” (Smits 2008: 111). From this approach, the Chinese graves in St. John’s can be regarded as a “new cultural product” which combines the elements of both the early Chinese immigrants’ home and host society and therefore represents their transnational identity.

Material Expressions of Chinese Identity in St. John’s

20 The twenty-one headstones which contain legible hometowns indicate that all of the immigrants originated in the same region in southern China, Siyi, which literally means “Four Districts,” and is located in southern Guangdong (Canton) Province. This supports information recorded in the Newfoundland Register: Arrivals & Outward Registration that shows between June 4, 1910 and March 26, 1949 all the Chinese immigrants were from Guangdong Province, and about 90 per cent of them from the region of Siyi (Li 2014: 51). Siyi includes four counties or districts: Kaiping, Taishan, Enping and Xinhui, and is well known as the birthplace of many overseas Chinese. For example, the town of Chikan in Kaiping has a population of 46,000 while there are currently 90,000 Chinese living overseas who are originally from there (website of the town of Chikan, 2017). Further evidence of the close ties between Chikan and Canada is evidenced in an area of the town known as “Canada Village” because the buildings were mainly constructed by Chinese Canadians in the 1920s and 1930s (website of the town of Chikan, 2017).

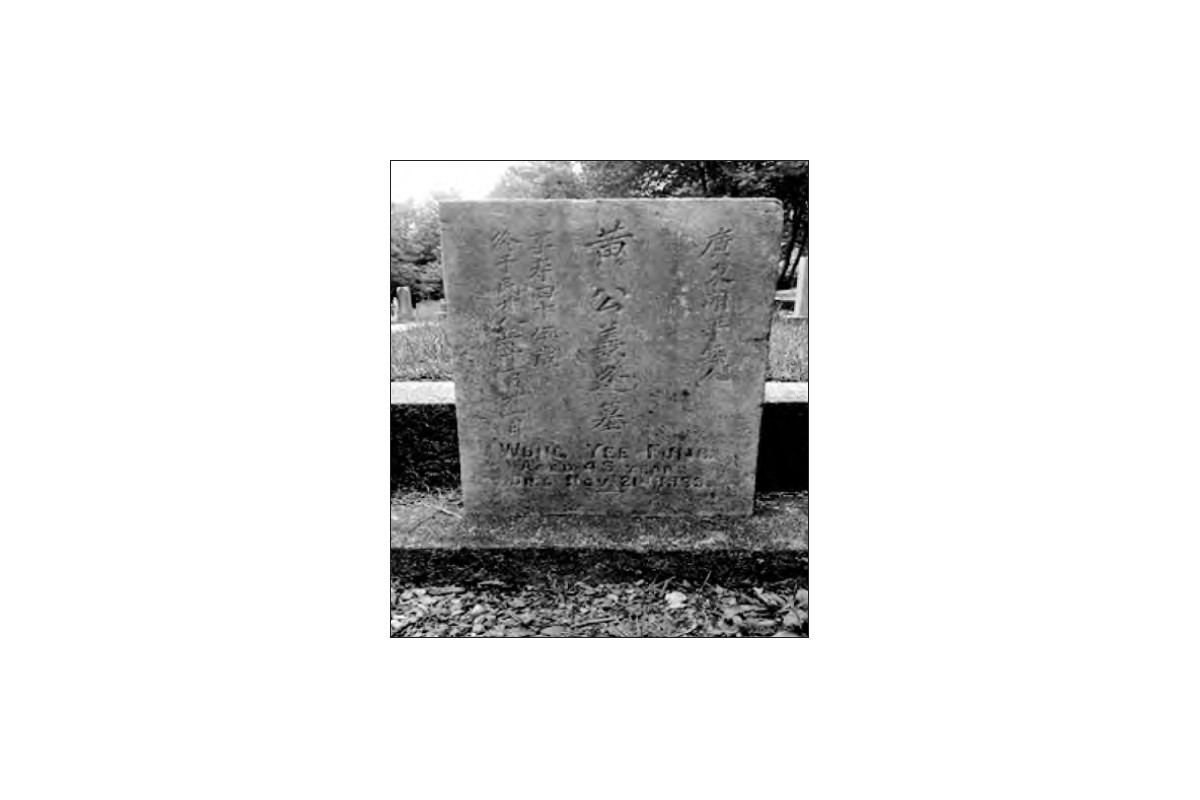

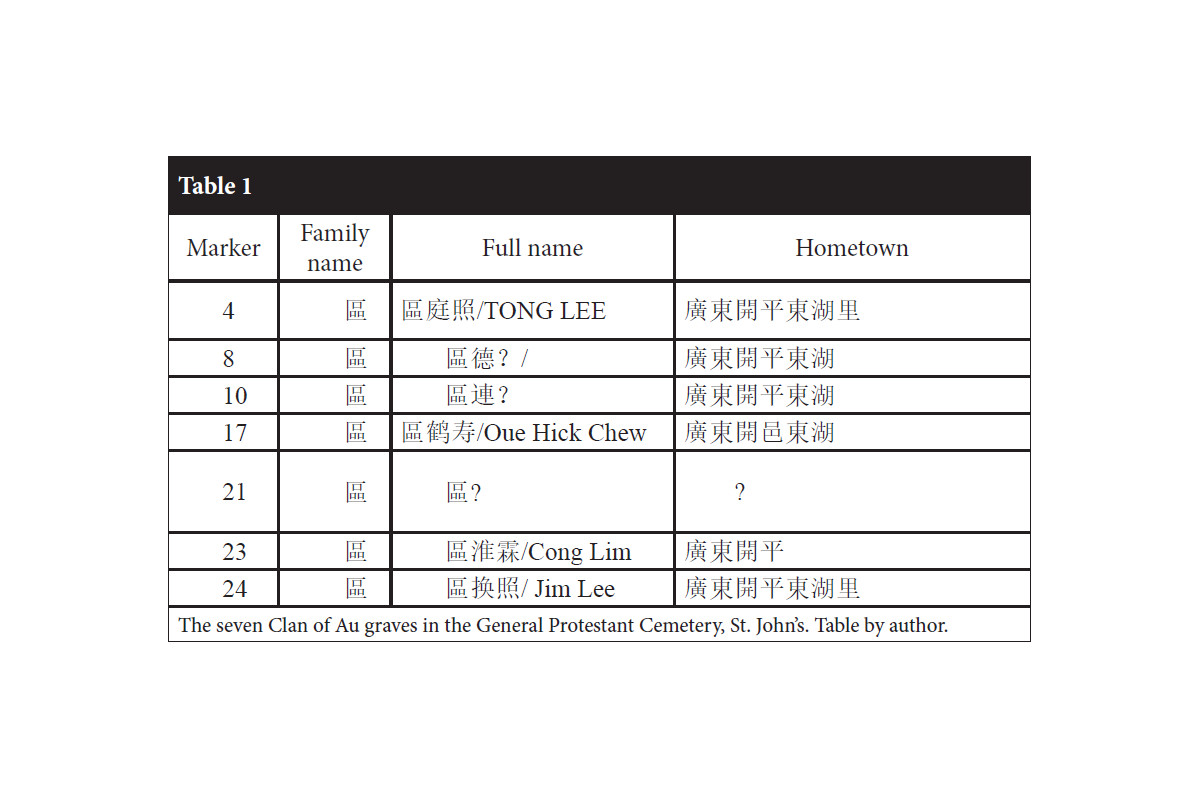

21 As explained above, the mode of chain immigration that shaped early Chinese settlement in St. John’s meant that overseas Chinese sponsored their families, relatives, kinsmen, clansmen or at least people from the same hometown (in many cases, the same hometown meant the same clan as well as same surname) to join them. As a result of this immigration mode, the twenty-one Chinese headstones containing hometown information shows that the immigrants were primarily from three counties or districts in the Siyi region of China: Kaiping (11), Taishan (9), and Enping (1). More specifically, in the group from Kaiping, five of the deceased were from the same neighborhood Donghu (東湖). At the same time, seven of them had the same family name of Au or Ou (區) (Table 1). Of the nine men from Taishan, five had the same family name of Hong(熊). Headstone inscriptions therefore reflect the strong linkages among early Chinese immigrants based on clanship and hometown.

22 Each inscription includes information such as the person’s name, date of death, age, and birthplace written both in Chinese and in English or an anglicized form. For example, marker 2 lists the name, age, and death date in both English—“KUNG YUEN SHING (anglicized names) AGED 19 YEARS, DIED DEC”—and Chinese—龔公遠勝 (Chinese name) 墓,廣 東恩平縣人,享寿拾九歲 (age in Chinese),终于民國廿九年十二月卅一日 (date of death in Chinese). Significantly, however, the Chinese inscription includes a birthplace in China, “廣東恩平縣人” (Enping County, Guangdong), but this information is not mentioned in the English inscription. The pattern is repeated across the twenty-one headstones that legibly list birthplaces; in eighteen cases these appear solely in Chinese. Early Chinese immigrants’ commitment to their birthplace is strongly expressed in this way; they make a clear declaration that their home place has not been forgotten. However, that the information appears only in Chinese also indicates that it is intended for a Chinese audience. Local residents of St. John’s, who during this time period lumped all Chinese under the general term of “Chinamen,” presumably would not know or care about the specific hometowns of these immigrants.

23 Although an immigrant’s birthplace engraved on a headstone was inconsequential to members of the mainstream society of St. John’s, it would have been very significant to early members of the Chinese community. Without immediate family members, a shared hometown and clan would have represented their relationship to other Chinese immigrants. It provided an important way to connect with one another and underscored an obligation to help each other in the face of inevitable death. Chung, Frampton and Murphy comment that “countrymen—often distant relatives or relatives or people from the same district—replaced the immediate family members as the main figures in the funerary process” (2005: 111). The practice of engraving a person’s hometown on their headstone in Chinese emphasized the individual’s ties to other members of the Chinese community in St. John’s at the same time it maintained a connection to their birthplace and family overseas.

24 Nicolas Smits points out that “the discrimination that Chinese Americans faced in their everyday lives often served to solidify the community around its members’ shared experiences and cultural heritage” (2008: 113). Thus discrimination and isolation from the larger host community led Chinese immigrants to form associations based on clanship as well as region of origin (locality and district associations) across North America (Li 1998: 96). These associations were initially formed to help provide their members with social, economic, and at times, legal assistance. In St. John’s, there were two Chinese clan associations founded between the 1920s and 1930s. One was the Tai Mei Club for those from Kaiping within the clan of Au or Ou; the other was the Hong Hang Society for countrymen from Taishan. Both clan associations had their own properties where members gathered for social, leisure, or other purposes.

25 One of the responsibilities of these clan associations was to manage funeral arrangements for their members. In traditional Chinese culture, descendants are obligated to take care of their deceased ancestors by organizing proper funerals and annual remembrance services. As Chace notes, “individuals believed that such measures not only benefited the deceased but also ensured a shower of blessings from the contented ancestor on the descendants” (2005: 28). For the deceased, the offerings from their descendants promised a better afterlife.

26 Many Chinese immigrants wished to be buried in their hometown in China to benefit both ancestors and descendants. As a result, it was very popular in the late 19th and early 20th century for the remains of Chinese immigrants, especially those from Cantonese area, to be exhumed and shipped back to their birthplace for reburial. As Roberta Greenwood notes,

27 Without family members in North America, regional or clan associations took on the responsibility for arranging funerals and shipping back remains.

28 This study, however, could not find any evidence that reburial was a tradition in the St. John’s Chinese community. Perhaps the much longer distance between St. John’s and China, compared to Chinese communities located along or close to the west coast, made shipping remains unfeasible. Nonetheless, Chinese clan groups in St. John’s still played an important role in their countrymen’s burials. Although there is no record documenting who paid for the erection of headstones on the Chinese graves in the General Protestant Cemetery, it is clear from headstone 11 that at least sometimes the clan associations were responsible. The inscription on this marker for Hong Kim indicates that it was erected by the Hong Hang Society.

29 In some situations, the Chinese community expanded beyond geographical and clan boundaries and acted as a united ethnic community. For example, the memorial (marker 25) erected by the Chinese Association of Newfoundland and Labrador (CANL) in 1988, is for every Chinese person buried there. CANL also holds an annual flower service at the memorial. As well, the early 20th century newspapers in St. John’s describe funerals attended by almost every Chinese resident. At Wah Hung’s funeral in 1912, “the laundrymen from all the shops (except one) in the city were present, perhaps four or five remaining to attend to callers” (Evening Herald, June 26, 1912). Writing of the funeral of two Chinese in 1919 who were buried in the General Protestant Cemetery, a reporter notes that “all the countrymen of the deceased in the city attended the funeral” (Evening Herald, April 8, 1919). In 1924, when Hon Fen was buried in the cemetery, “the obsequies were attended by a large number of Chinese citizens” (Evening Telegram, December 1, 1924). Finally, a funeral for Hong Sai Tee (who was buried in the Catholic Mount Carmel Cemetery) held later that year, “was attended by practically all the Chinese in the city” (Evening Telegram, November 27, 1924). Respect for the dead was expressed not only at funerals, but also by visiting gravesites. The May 10, 1909 issue of the Evening Chronicle recorded that

30 Rituals mark the Chinese lifecycle of birth, marriage, and death. Through these rituals, a Chinese person confirms that he or she steps into a different stage of their life and that he or she is a member of a community, since every ritual is a community event. Arguably, death took on more importance as a ritual occasion in a bachelor society without births or marriages to celebrate. Death, and accompanying funerals, processions, interments, and post-funeral visits, became an important way to reaffirm that every deceased person was a valued member of the St. John’s Chinese community. They reassured community members that no one needed to worry about their afterlife in an alien society. The funerals and processions—which almost all the Chinese community members participated in—became one of the few ways for Chinese immigrants to publically present their identities to both themselves and the host community. Similarly, the headstones erected in the General Protestant Cemetery for members of the Chinese community by their countrymen were a tangible way to express, as well as reinforce, Chinese ethnic identity in a public space.

Adapting to the Host Community

31 Wendy Rouse notes that, in the context of California, Chinese were “flexible and adaptive even in death … this is especially important if we are to recognize that no people, no matter how traditional, ever remain culturally static” (2005: 104). Chinese immigrants in St. John’s were equally as flexible, as their adaptions to religious belief and language reflect.

32 Adopting Christianity was one of the most important ways for Chinese immigrants throughout North America to adjust to a new culture. In St. John’s, many Chinese immigrants converted to Christianity and went to church services and programs. This partly explains why they were buried in the General Protestant Cemetery. Moreover, Chinese funerals were officiated by ministers from churches in St. John’s. For example, in 1912 Rev. F. R. Matthews of the Wesley Methodist Church conducted a funeral service for Wah Hung that included singing the hymn “There’s a Land that is Fairer than Day” (Evening Herald, June 26, 1912). In 1919 and 1922, Rev. W. B. Bugden, minister of the Wesley Methodist Church, led funeral services for Chinese residents (Evening Herald, April 8, 1919; Evening Telegram, May 8, 1922). Rev. R. E. Fairbairn of George Street United Church presided over a graveside service for Hon Fen in the General Protestant Cemetery in 1924 (Evening Telegram, December 1).

33 Traditionally, Chinese funeral custom includes a variety of superstitions. Chinese, especially those from Guangdong Province, relied on fengshui (literally “wind and water,” or geomancy theory) to determine proper burial sites. As Wendy Rouse explains, “The ultimate goal of fengshui … is to please the ancestor with a comfortable resting place where a balance of qi, vital energy, can be found” (2005: 24) However, in St. John’s, the plots assigned by the Church left Chinese immigrants no options to practice this ritual. Moreover, during the funeral procession from their home or the undertaker’s to the cemetery, the Chinese usually performed a series of rituals to provide the deceased with comforts. As Chung and Wegars note:

34 The authors also observe that music was a way of distracting evil spirits (2005: 5). However, descriptions of funeral processions in newspapers in St. John’s suggest the absence of these traditional elements in immigrant Chinese funerals. It appears that Chinese newcomers failed to continue these traditions in their host society. Without the close support of family, and away from the traditional ritual practices of their home villages, Chinese immigrants turned to western religion to address the inevitability of death. In St. John’s, as elsewhere, the adoption of western funeral customs reflects the creation of a new social community and adaption to new cultural practices (Chace 2005: 47-48).

35 Belief systems can be reflected in the decorations found on headstones. Generally, the design and decoration of Chinese headstones in the General Protestant Cemetery is very plain and many are simply upright rectangle markers. Those that are decorated are engraved with popular religious motifs: a hand holding ivy with a finger pointing towards a flower (marker 26, 21, 19, 14) or with a finger pointing upward (marker 23); ivy (marker 17), sometimes with a cross in the middle (marker 10, 8); willow (marker 12); clasped hands (marker of Tom Yee Sing, a broken marker in the bottom left corner); or an open book, which might represent the Bible (marker 27 and marker 6). With some individual differences, these religious symbols are also used widely on the headstones of local residents in the cemetery. The shared religious motifs, burial in a Protestant cemetery, and the presence of ministers at Chinese funerals, all suggest that Chinese immigrants in St. John’s were trying to shape their death practices and beliefs to fit into larger cultural and religious groups—at least in public. In Alison Marshall’s research on Chinese communities in western Manitoba, she uses the term “religious ambivalence” to describe how “in public most people self-identified as Christian, while in private they were more traditionally Chinese” (2009: 577). This pattern may well characterize the experience of early Chinese immigrants buried in St. John’s.

36 Beyond religion, Chinese immigrants attempted to adapt to other aspects of community life. Once in St. John’s, a city dominated by English speakers, arrivals often “invented” an anglicized or English name for themselves. Chinese names inscribed on headstones in the General Protestant Cemetery appear in a large font size and are usually positioned in the middle of the stone, clearly prioritizing the original nationality of the Chinese immigrants. That said, every headstone includes an anglicized name which the person probably only used in St. John’s. The engraving of this “second name” on the headstones indicates that the deceased were immigrants, not just sojourners (Chung and Neziman 2005: 190). They were trying to accommodate the host culture while preserving Chinese ethnicity.

37 Usually, Chinese names can be anglicized naturally according to their pronunciations. For example:

Marker 3: 龔遠勝 = Kung Yuen Shing

Marker 5: 黄義逢 = Wong Yee Fung

Marker 12: 熊進盛 = Hong Dean Shing

38 However, sometimes anglicized names were not transliterated from formal Chinese names. Chinese immigrants adopted a conventional English name directly, sometimes based on informal names or nicknames, or the names were newly selected to make their identity more recognizable and pronounceable to the Englishspeaking population of St. John’s, since even their anglicized Chinese name was still too difficult for locals to pronounce. Taking on an English name represented a substantial step toward assimilation into the host culture. For example, 鄭長業 was known as “Jack” Chong and 余發 和 as “Charlie” Yee.

39 There are also many cases when the Chinese and anglicized names do not match each other phonemically. It is unknown how individuals got these names. For example, 區庭照 became Tong Lee, 區德照was Pa Chew, 區連齊 identified as Tie Lee, and 區换照 took on Jim Lee. These anglicized names omit family names like “Au or Ou,” perhaps because these were barely used in the immigrant’s public lives in St. John’s. For example, the local media would assume that a name such as Kim Lee, without the surname Au, was the full Chinese name. Therefore, Kim Lee was called Mr. Kim Lee or Mr. Lee instead of Mr. Au (Trade Review, March 20, 1919). TheEncyclopedia of Newfoundland and Labrador also listed his name as Lee, Kim (Fitzgerald, Hong, Ping et al. 1991: 270).

40 Comparing the burial records held in the cemetery archive with the inscriptions, mistakes also arise in the names. For instance, Hong should be the family name in the name of Hong King (marker 11), but the burial record indicates that King is the surname. A similar mistake happened to Hong Yuen (marker 19). Jim Lee’s burial record (marker 24) incorrectly lists him as Lee, Jim. Additionally, the person documenting the burial information simply indicated “Jack Chinese” in the record; this is likely Jack Chong on marker 1.

41 Thus, due to cultural differences Chinese names in terms of both the order and pronunciation often confused non-Chinese speakers. Anglicized names, developed as a result of different strategies, were used by Chinese in St. John’s mainly for the benefit of members of their host community. As Fred Blake summarizes from his research on Chinese markers in Valhalla Cemetery in St. Louis, Missouri, “we can see a complex process in which the symbolic resources of two literate civilizations are inscribed together on the same slabs of stone” (1993: 79). Although these “second” names often had nothing to do with the immigrants’ original names, Chinese immigrants buried in St. John’s nevertheless accepted them and they are now permanently engraved on their headstones. The anglicized names suggest a willingness on the part of the early Chinese to integrate themselves into the local community and to gain acceptance. As Chung, Frampton and Murphy argue, immigrants “made accommodations to their new environment and circumstances from the outset” (2005: 138). This process of adaptation and accommodation is especially reflected in material ways, as grave markers convincingly demonstrate how St. John’s Chinese immigrants “progressively relinquished” Chinese cultural identity and instead adopted westernized identities (Abraham and Wegars, 2005: 114).

Conclusion

42 Sue Fawn Chung and Reiko Neizman discovered that the gravestones in a Chinese cemetery in Hawaii “reinforce the connection between the living and the dead as a Chinese group.” (2005: 190). However, “modifications in the performance of ... burial practices have been made to incorporate themselves into a larger group where they live” (2005: 190). The same can be argued for the General Protestant Cemetery in St. John’s. Headstones marking Chinese graves in the cemetery hold insights into the formation of a transnational identity among Chinese immigrants in early 20th-century St. John’s. Important clues to the complex process by which early Chinese immigrants acquired hybrid identities are revealed in the material record. Through location, design, decoration, and inscriptions, the headstones of Chinese immigrants attest to both their persistence in keeping a Chinese identity and their willingness to adapt to the new, host society.

Table 2

This research report developed from a project conducted by The Heritage Foundation of Newfoundland and Labrador. An earlier article by Terra Barrett, Heather Elliot, Dale Jarvis, Michael Philpott, and Li Xingpei was published in vol. 30, no. 4 of the Newfoundland Ancestor (2016) and the newsletter of The Heritage Foundation of Newfoundland and Labrador. I would like to thank my Heritage Foundation colleagues for their contributions to the research on which this report is based. I also would like to express my gratitude to the peer reviewer from this journal and my classmates from the graduate material culture course at the Department of Folklore, Memorial University of Newfoundland. I would like to especially thank Dr. Diane Tye, the course instructor, who spent a considerable amount of time on my paper to improve it vastly.