Articles

The Legacy of a Hidden Camera: Acts of Making in Japanese-Canadian Internment Camps During the Second World War, as Depicted in Tom Matsui’s Photograph Collection

Abstract

This paper adds to growing documentation of various object making practices that occurred during the internment of Japanese Canadians during the Second World War. The arts-informed research for the paper was conducted as part of the Landscapes of Injustice Project (LOI), which explores the dispossession of Japanese Canadian property during this time. In response to the massive loss of their possessions, out of necessity Japanese Canadians made gardens, furniture, and buildings, among other objects, while in camps. I share some diverse examples of camp-based making before deeply exploring the life and photographs of Tom Matsui. Tom’s photographs show evidence of making in camps, but are also material culture made in a camp. I suggest they have an important message of political resistance embedded in their creation.

Résumé

Cet article s’ajoute à la documentation croissante sur les diverses pratiques de fabrication d’objets qui ont eu lieu durant l’internement des Canadiens Japonais pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale. La recherche pour cet article a été menée dans le cadre du projet Landscapes of Injustice [Paysages d’Injustice](LOI), un projet de partenariat CRSH qui explore la dépossession de biens qui a également eu lieu pendant ce temps. En réaction à la perte massive de leurs possessions, les Canadiens Japonais ont par nécessité créé, entre autres, des jardins, des meubles, des écoles et des maisons dans les camps. J’expose divers exemples de fabrication d’objets dans les camps avant d’explorer plus en profondeur la vie et les photographies de Tom Matsui. Les photographies de Tom attestent de la fabrication d’objets, mais aussi de la culture matérielle dans les camps. Je suggère que la création de ces photographies véhicule un important message de résistance politique.

Introduction

1 During the Second World War, as a response to the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour in December 1941, Japanese Canadians living within 100 miles of British Columbia’s coast were uprooted from their homes by the Canadian government. Of the roughly 22,000 Japanese Canadians living in coastal British Columbia prewar, 12,000 were sent to a series of internment2 camps in the interior part of the province, 4,000 were sent to work on sugar beet farms in Manitoba and Alberta, and over 1,000 were sent to self-supporting camps (where they paid for the cost of their internment). Still others were sent to road camps throughout British Columbia, or prisoner of war camps in Northern Ontario. Although the war ended in 1945, Japanese Canadians were not free to return to the coast until April 1, 1949. During this time, Japanese Canadian homes, cars, boats, and other possessions were destroyed or sold by the Canadian government’s Office of the Custodian of Enemy Property. The proceeds of the sale of Japanese Canadian property helped fund the internment. Because of these actions, the only possessions most Japanese Canadians had postwar were things they were able to bring when they moved, or things they made in the aftermath of their uprooting.

2 Broader stories associated with Japanese Canadian internment have received considerable attention from a range of scholars (Adachi 1976; Kobayashi 1992; McAllister 2010; Oikawa 2012; Robinson 2009; Sugiman 2009, 2007, 2004; Sunahara 1981). The history of property loss, however, has received comparatively little attention until quite recently, thanks to the Landscapes of Injustice Project (LOI), a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) Partnership Project working to fill this research gap. LOI connects institutions across Canada in researching and disseminating the history of Japanese Canadian property dispossession. Multiple clusters are exploring different facets of property loss through a variety of sources and methods: historical GIS, legal history, land title and government records, community and provincial records, and oral history. The project started in 2014 and has since generated both scholarly production and media attention.3 In 2018, the research phase transitions into dissemination and different clusters will begin sharing research with the public through websites, museum exhibitions, and teacher education kits.

3 I was a postdoctoral fellow with LOI beginning in 2015, and remain an affiliated researcher. As a fellow, I helped manage the oral history research cluster. I interviewed members of the Japanese Canadian community and directed a team of graduate student researchers in conducting their own interviews. I worked under the guidance of Dr. Pamela Sugiman, with advice from other LOI research leads. At the time of writing, LOI has collected approximately 100 new interviews about the property loss, and the project is still actively collecting. One of the goals of LOI is to help the narratives of loss move outside of the cultural community, so non-Japanese Canadians (such as myself) can learn about and from them.

4 I admittedly had little knowledge of the experiences of Japanese Canadians during the 1940s until I began working for LOI, but was immediately drawn to the stories I heard. I am a material culture researcher who uses oral history as a method. Most often, my practice involves talking with people about things that they either own or have made. I am curious as to how making things can help people feel at home, can communicate cultural messages when words fail, can render memories concrete, and can express resistance against outside forces. I should note I use words like making, creating, and art in ways that define them quite broadly, drawing from an array of perspectives in anthropology, folklore studies, adult education, and arts-informed research to frame my investigations into material culture (see Adamson 2007; Glassie 1968; Ingold 2000; MacEachren 2001). This epistemological range is reflected in the breadth of what I examine as examples of cultural production. In this paper, I explore the loss and creation narratives of a handful of participants to set context before focusing on the story of Tom Matsui (1927-2015), and a now archived collection of photographs he took while interned in Lillooet, British Columbia.

How I Have Written: Arts-informed Research

5 This paper uses an arts-informed approach to research—a qualitative methodology based on and inspired by the arts, and rooted in in the discipline of education (Knowles and Cole 2008). The goal of arts-informed research is to draw together the rigor of academic enquiry with the potential of artistic practices to inspire and educate a broad range of people. One of the methodology’s main tenets is to create research representations that are engaging and accessible beyond academic audiences. Research representations should also bear evidence of the researcher throughout the work, most often using reflexive, personally revealing writing practicessimilar to those used in autoethnography (for examples of researcher presence in scholarship, see Behar 1996; Cole 2002; Cole and Knowles 2001; Hatch and Wisneiewski 1995; Lawrence-Lightfoot and Davis 1997; Leggo 2004; Martien 1996; Muchmore 2001; Neilsen 1998; Shields 2003; Tye 2010; Westerman 2006). Education researcher Elliott Eisner writes that the use of the arts in research is best suited to generating questions and evocative outcomes. He notes several contributions of the arts to knowledge: it generates and promotes empathy, provides fresh perspective, and helps connect people with personal subjectivities (2008). While the overall LOI project takes a more conventional approach to historical research, I have worked from the beginning with artful intent. I sought artists to interview, asked questions about art making and material culture, and took descriptive notes following my interviews with an eye to include the descriptions in publications. I work within arts-informed research, as opposed to a methodology that distills observations into more traditional academic questioning and language, because I believe the qualities Eisner describes above are an important aspect of intercultural understanding. Rather than drawing conclusions about the understudied area of Japanese Canadian internment making, I want to create a space for readers to see the world, for a few moments, through the eyes of the people who made the objects.

6 Education scholars Gary Knowles and Ardra Cole propose eight qualities of “goodness” that define arts-informed research: intentionality, researcher presence, aesthetic quality, holistic quality, communicability, methodological commitment, knowledge advancement, and contributions (2008). These qualities benefit from explanatory comments. By intentionality, Knowles and Cole suggest a researcher should intend to use their work to create transformational shifts in audiences. Researcher presence, aesthetic quality, holistic quality and communicability all relate to the products of research: essentially, products generated should contain evidence of the researcher and be accessible to broad audiences. Methodological commitment means a researcher should aim to create arts-informed work and maintain the intent to the end of the process. Knowledge advancement is generative and fluid; Knowles and Cole suggest knowledge claims must be made with some amount of ambiguity to allow for multiple interpretations of the work. Lastly, contributions of arts-informed research need not be new theories, or irrefutable arguments. Rather, arts-informed research allows for researchers to raise questions, share emotions, and provide space for an audience to draw conclusions based on what they see. Again, this methodology bears similarities to autoethnography, which according to Carolyn Ellis, Tony E. Adams, and Arthur P. Bochner aims to produce accessible texts through which a researcher can address “wider and more diverse mass audiences … a move that can make personal and social change possible for more people” (2011). Arts-informed research also expands the possibility to engage with multiple art forms, such as film, painting, dance, song, theatre, exhibitions, craft, installation, and fiction, among other genres.

7 An act of creation is a relationship between a maker and audience, so I look forward to a multiplicity of interpretations of this narrative article. I explain these qualities as a reminder that arts-informed research as a methodology has a slightly different intention from more traditional social sciences research, which may help readers interpret my text. I do not intend to argue or conclude anything, but instead create a space for learning about a difficult aspect of Canadian history. For that reason, what might otherwise be considered analysis is embedded within the text and not parcelled out in a separate section. The text has been written in order to prioritize a narrative flow. There are no firm conclusions; I invite readers to draw their own. Working in this style in the context of academia is a deliberate effort to expand the boundaries around what counts as knowledge and who makes those decisions. Engaging in this style is a choice to emphasize that a key aspect of this research is the emotive and evocative narratives surrounding the material culture associated with the internment of Japanese Canadians rather than object details, which in many cases no longer exist.

8 As a final note about my methodological stance, I share poet and ethnographer Lorri Neilsen’s view of inquiry, which recognizes the importance of relationships, and that “the quality of our attention to the relationships can be the difference between ... doing to and doing with, between clumsy and wasteful, and effective and generative.” Neilsen also writes that for her, “the quality of [her] relationship with individuals, with groups, in contexts and systems of contexts, has replaced the quality of [her] relationship with method as the critical feature ...” of her work (1998: 271). Beyond the reflexivity required of arts-informed research, by including elements of my own experiences as a researcher I am hoping to honour the relationships I formed with the narrators. I am also hoping to establish a relationship with the reader that creates space for learning. As I mentioned, I did not know much about the difficult, troubling history of Japanese Canadian internment before I started working for LOI. While I did background research before interviews, it was in the relationships I formed with narrators where I deeply learned about the internment. I therefore share my personal responses to invite the reader to join me in this transformative learning experience.

Preliminary Stories of Loss and Making in Japanese Canadian Internment Camps

9 The main focus of this text are interviews I conducted with Tom Matsui and his photographic collection. Tom was a teenager when the internment era began, and he and his family chose to relocate from downtown Vancouver to a self-supporting camp in Lillooet, British Columbia. Tom had taken up photography shortly before the events of Pearl Harbour, and brought his camera and some developing chemicals with him when his family moved. The bravery of this action must be acknowledged. As Namiko Kunimoto writes, after the attack on Pearl Harbour “Japanese-Canadian family photographs and images from Japan were confiscated as ‘evidence’ of disloyalty to Canada, and … the British Columbia Securities Commission (BCSC) forbade anyone of Japanese descent to possess cameras, even before the relocation had begun” (2004: 129). While Tom was not alone in his practice—other photography exists from the period—he, along with other internees taking pictures, had to “work around the laws” (2004: 135). The photographs Tom took in Lillooet are fascinating: they provide glimpses of the lived experience of the Matsui family, showing how they made a new life for themselves in the aftermath of their uprooting from Vancouver. They also reveal elements of Tom’s perspective on the internment, like a visual diary. Though it is anachronistic to read the photographs this way, I see the photos as connected to images created in contemporary participatory action research. I explore the photographs in relation to this research framework later.

10 First, though, to contextualize Tom’s stories and images, I will share a few memories of property loss from other Japanese Canadians that I heard during my research with LOI. I include these narratives because they complement Tom’s experiences of discrimination in pre-war Vancouver. The oral history cluster of LOI focuses on collecting memories of property loss, understanding the ways those losses were experienced by individuals and families, and considers how the effects of loss rippled throughout multiple generations. I interviewed people with direct lived experience of the internment (issei and nisei, meaning first and second generation Canadians), but also their children and grandchildren (sansei and yonsei, meaning third and fourth generation Canadians). The vividness of the issei and nisei narratives was incomparable. Tom was a nisei, one of an increasingly limited number of Japanese Canadians who have direct memories of the internment.

11 Jeanne Ikeda-Douglas is currently a Toronto resident; she was a child in Vancouver during the pre-war years. Like Tom, she is a nisei, and they both grew up in the Powell Street neighbourhood of Vancouver as children. I met both of them for their interviews at the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre in Toronto. In this first excerpt, Jeanne describes witnessing looting of former Japanese Canadian homes in Vancouver after residents were forced to leave:

12 I was stunned as I listened to her describe what she saw as a child during this interview. One of Jeanne’s sisters had become too ill to travel shortly before the uprooting, so her family stayed in Vancouver until the sister was well enough to travel. This allowed Jeanne and her mother to bear witness to the looting. Later, Jeanne describes the extreme difficulties faced by her family with an emphasis on displays of kindness shown to them by neighbours and friends: she remembers her mother being given badges that would identify them as Chinese, so they would not face racial persecution en route to the hospital to visit her sister. Jeanne describes friends who offered to take care of her family’s property and send it to them in the camp, and kind hospital nurses who cared for her sick sister. In another excerpt, Jeanne describes how her mother disposed of a precious family artifact to prevent it from being sold:

Especially in the excerpt about the samurai armour, Jeanne’s narratives paint an evocative picture of the desperation felt within the Japanese Canadian community at the time.

13 Cheryl Shoji is a Sansei who lives in Victoria, but grew up in Toronto. Cheryl’s mother and aunt grew up in Maple Ridge, British Columbia and were evicted during the war. Cheryl had what she would describe as a very typical Canadian childhood; her parents made considerable efforts to disconnect themselves from their Japanese Canadian heritage after the war. Cheryl and her siblings have made efforts in recent years, as their mother is aging, to understand their family history. I met Cheryl in her home in Victoria, and she showed me photos and scrapbooks she was working on. We had a very lovely afternoon eating snacks she prepared and drinking tea. Her cats wandered around in the background and can be heard on the interview. Here, Cheryl is referencing and then reading from a letter her aunt wrote, describing the internment:

14 An important generational disconnection between older Japanese Canadians and their children and grandchildren is apparent in Cheryl’s story. It is present in the excerpt where Cheryl recalls her mother encouraging her children not to explore things buried in the old family property. It is also there in the tone of the interview; the fact I experienced the interview as lovely reflects that we spent considerable time talking about intergenerational silences, rather than remembered events. These silences are common in Japanese Canadian internment narratives, as sociologist Pamela Sugiman notes (2004: 361-62). Sugiman writes that as a group, Japanese Canadians became preoccupied with “shedding the cultural markers of Japaneseness: the Japanese language, contact with Japanese Canadian peers and an appreciation of Japanese Canadian art forms” (361). I include Cheryl’s narrative in this paper here, situated alongside Tom Matsui’s story, to emphasize the significance of his efforts as an aging Japanese Canadian in creating a lasting memory of the internment with his archival photograph project.

15 As I collected narratives, and began researching those collected by other projects on a similar theme, I noticed sad stories of loss were often followed by stories of creation. The narratives were multilayered, to borrow a word Pamela Sugiman uses in describing the range of internment stories she has heard in her long research experience with Japanese Canadians. Sugiman describes “vivid memories of forced relocation, restricted mobility, finger-printing, registration and curfews, the loss of privacy, maggots, ticks, bedbugs, the stench of horse manure, [and the] separation of families …” along with stories of “acts of generosity and kindness on the part of hakujin (a Japanese term meaning “White”) neighbours,” and “stories of triumph alongside recollections of suffering” (2009: 190-91). The stories of creation I noticed sit alongside those of a more uplifting tone that Sugiman describes, and reflect the tendency she noticed in narrators to tell audiences that they are “more than their wartime experiences” (2009: 210).

16 The narratives about making did not necessarily immediately follow narratives about loss, but as people progressed through the war and what happened afterwards, making and creating became common themes. Sometimes the things created were physical objects, both large (homes and schools) and small (food, clothes, watches, toys, and so on). Sometimes there were physical alterations to landscapes, often through gardening. Other times, the making was more metaphorical, as people referenced making new opportunities for themselves through taking jobs, getting education that was denied to them during the war, or moving to new provinces. Making was also evident in a non-verbal way, through the beautiful homes that some elderly Japanese Canadians have created for themselves. For this paper, however, I will focus on wartime making that occurred in internment camp settings.

Art, Making, and Historical Injustice

17 The practice of making things flourishes in the most trying human circumstances. There is art created in wartime, after traumatic environmental events, through disease and disability, and because of political pressure. Practices of material culture, art, and craft-making have been documented in wartime South Africa, Germany, Great Britain, and America among other places (Alkema 2009; Carr 2013; Ensminger 2013; Mytum 2011; Seller 1996). Art practices also occur in refugee camps (Dudley 2011; Parkin 1999; Verrillo and MacLean 1993), and prisons (Baer 2005; Merriam 1998). Researchers have documented artmaking practices among survivors of violence, exploring narratives and other artful representations of traumatic memories (Agah, Mehr and Parsi 2007; Caruth 1996; Harlow 1998; LaCapra 1996; Lorentzen 1998).

18 Researchers and artists in the field of community arts engage with societal issues, using the arts to promote healing in communities divided by, for example, racism, political oppression, and environmental degradation (Barndt 2008; Carey and Sutton 2004; Lai and Ball 2002; Westerman 2006). Art-making is fundamental to the human condition, a way in which people come to understand the world around them, and a prime example and facilitator of human resilience. Again, in these examples, and in this paper, I define art broadly: art can mean culinary arts, gardening arts, and arts associated with carpentry and sewing, as well as more conventional music, painting, drawing and so on. Examining the material culture of difficult environments with a broad lens deepens our understanding of the lived experience of people in these places which, though created by hardship, become communities (Hinrichsen 1992; Holt 1981).

Acts of Making in Japanese American Internment Camps

19 Acts of making in Japanese American internment camps have been documented both academically and in the art world. From 2010-2011, the Renwick Gallery at the Smithsonian American Art Museum displayed the show The Art of Gaman, which featured folk craft created in WWII internment camps in the United States. Curated by Delphine Hirasuna, the first version of the show occurred in 2006. The show grew as it toured across the US, as visitors brought items out of storage for the curator to see (Obler 2011: 94). Hirasuna also produced a book (2005) featuring the objects from the original show. With basic, but sensitive contextual essays to ground the material, the artistry of the makers is wonderfully highlighted. A similarly sensitive book from 1952 by Allen Eaton called Beauty Behind Barbed Wire also documents the arts produced in Japanese American internment camps. Notably, Eaton, writing only a few years after the war, politicizes the internment by including text stating that internment violated the amendment rights of Japanese Americans and praising Hawaii for choosing not to incarcerate people of Japanese heritage. The book has beautiful photographs of gardens, warm images of home interiors with handmade furniture, and detailed shots of carvings and other traditional crafts. Eaton describes flower arranging classes, art exhibitions, music and theatre festivals, as well as the creation of carts, staircases, children’s toys and jewellery. He is effusive in his praise for Japanese American creativity during the War.

20 Acts of making in the Japanese American context have been explored academically as well. Jane Dusselier (2004) notes woodworking (both large and small scale), landscaping and gardening, sewing, knitting, and flower arranging as crafts practiced by Japanese Americans that helped make the camps bearable. People literally remade the places where they lived. In her book Artifacts of Loss (2008), Dusselier argues art creation was central to the mental survival of internees, rather than a product of leisure time (a common belief at the time) (Bangarth 2012: 129). Connie Chiang (2010) explores the histories of internment in the United States with an environmental lens, showing how the physical properties of the areas where camps were built influenced the lives of Japanese Americans. American camps were often built in hot desert states (like Arizona), so planting gardens for food and shade were critically important first acts of creation. Later, once basic needs were met, Japanese Americans could practice occasional recreation, such as fishing and digging for fossilized sea shells to use in craft projects. Finally, Chiang describes welding as a common job for Japanese Americans that involved craft skills, as they repaired water pipes that provided irrigation to communities in the American desert. Making throughout internment served both aesthetic purposes and provided basic needs.

21 Food was another important area of creation that, while essential for life, also allowed Japanese Americans to assert cultural identities. Jane Dusselier (2002) describes tremendous energies Japanese Americans put into building tofu and shoyu factories, planning gardens, and trying to recreate traditional foods with what was available to them. She also notes food making allowed for collective engagement, as mess halls became sites for rallies.

22 In addition to artful utilitarian work, material culture was produced to support performances that happened in Japanese American camps, such as those associated with theatre and music. Writing about theatre in Japanese American internment camps, Emily Colborn-Roxworthy describes the complexity of activities at Manzanar National Historic Site. Manzanar had a long history of public performance, mixing both Japanese cultural performances like Kabuki theatre and Odori dance, and American magic tricks, popular music, singing, and tap dancing (2007: 206). Colburn-Roxworthy notes these performances were sites of Japanese American resistance to the assimilation goals of the American government; big band performances were often followed by traditional Japanese-language theatrical chants, for example, at performances open to the camp and surrounding communities. For both the Americanized and Japanese cultural performances, costumes, props and other objects were created in the camp. Minako Waseda explores music making in the American camps, noting that while the internment had serious consequences for Japanese American lives, the effect on music making “can be characterized as constructive and even positive” (2005: 172). She argues the camps concentrated the population and actually “spawned the revival of previously declining [traditional] genres” (182). Waseda notes interned Japanese Americans crafted performance necessities from local woods, or arranged to visit their homes to find costumes hidden at the time of relocation.

23 There has been little documentation about the parallel experiences of making in Canadian camps, though it is likely similarly rich practices took place. One rare piece of Canadian research is Kirsten McAllister’s (2006) exploration of camp photography, based on archival collections from the Nikkei National Museum in Burnaby, British Columbia (previously known as the Japanese Canadian Museum). Another is the work of Namiko Kunimoto, whose study of Japanese Canadian family photography albums suggests photographs gave internees a sense of stability during a “time of transience and powerlessness” (2004: 129). The lack of research on camp making in Canada does not reflect a lack of materials. There are collections both in private homes and in institutions like the Nikkei National Museum. Additionally, the internment remains not far from the minds of many Japanese Canadians; younger Japanese Canadians are beginning to investigate their heritage, and create contemporary artistic responses to the wartime history, often inspired by objects held in or missing from their families (these artists include Chris Hope, Cindy Mochizuki, Emma Nishimura, and Laura Shintani, among others). Contemporary art and material culture created to explore internment stories is another rich area for research.

Preliminary Japanese Canadian Stories of Making

24 Having set the context for my perspective on artmaking as an example of community and human resilience in the face of difficulty, and with the spectrum of creative action documented in the American context as a starting point, I will now share some Japanese Canadian narratives of creation collected from the LOI project. As I was interviewing Japanese Canadians (including Canadians of Japanese descent who do not identify as being part of the cultural community), I heard references to making that ranged from the personal to the collective. Jeanne Ikeda-Douglas shared a story about how her internment community built a school for the local children:

25 Some of the making narratives were about making for individual people rather than a community. Furniture making was common in internment camps, since the furniture provided to Japanese Canadians was quite basic. Here, Aiko Murakami and her son Michael Murakami, who were interviewed by myself and Momoye Sugiman, a research assistant, talk about two pieces of furniture made for Aiko (note, this interview transcript is dialogic, since it featured four people):

26 Sewing was an historically important activity for Japanese Canadian women (see the recent online exhibition by the Nikkei National Museum, “Our Mother’s Patterns”). It was a profession women could pursue without much racial prejudice in the early 20th century. Sewing continued in camps, as women made and mended clothes for their families and wider community. Here,Emma Nishimura, a yonsei, discusses finding patterns that belonged to her grandmother Mary:

27 Emma’s excitement at finding this concrete connection to her grandmother’s history was palpable, and is an example of the lingering effect of the narrative silences I mentioned earlier. Emma continues to be inspired by the drafting books and the tangible connection they provide to untold pieces of her family’s history.

28 Taken together, these brief narratives are glimpses into rich histories of creative action that occurred in Japanese Canadian camps. Outside of interviews, I heard anecdotes about which magazines made the best origami, secret sake breweries hidden from RCMP officers, and handmade decorations for dances made of scrap fabrics. In addition to the furniture and the dress patterns, I also saw photographs and albums, drawings and paintings, handmade bowls and dolls.

29 One of the most evocative combinations of material culture and narrative I encountered was Tom Matsui and his photographs. His story and photographs provide an intimate portrait of life in the self-supporting camp of Lillooet, British Columbia. Tom was a maker in the internment camp, through photography and various carpentry projects. Through his photography, he also documented slices of his community where making was vividly apparent. Lastly, in his commitment to making historical documentation, evidenced later in his life through his photo album compilations, he embodies the concept of making as a positive, community-building response to a historical injustice; he is trying to fill the narrative silence for future generations.

Getting to Know Tom Matsui

30 I interviewed Tom twice at the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre in Toronto and met him a handful of other times while visiting the Centre as a researcher. The Centre, a former factory in Don Mills, Toronto, is a beautiful building which serves as a cultural hub for Japanese Canadians in eastern Canada. There is a small museum in the Centre with a thriving group of archival volunteers, of which Tom was one. The volunteers assist in translating Japanese, identifying and labelling photographs, and in the general organization and care of the collection. They are a community of friends who are passionate about history, and a considerable asset to the Centre.

31 When I spoke with Tom, he was in the process of donating his personal photographic collection to the Centre’s archives. We used the photographs as a focus for our conversations. He had spent considerable time scanning and digitally correcting his older images, and added typed captions underneath the reproductions. The photographs we focused on were taken in the 1930s and 1940s with his small personal camera. They are all black and white, and often blurred at the edges, a reflection of the poor quality of lens. It was, he said often, a cheap, small camera.

32 Tom’s photographs allow contemporary viewers to glimpse the internment experience through the eyes of a 15-year-old young man. They are important to read not as contemporary photographs, but as visual images created in an extreme situation. Kristen McAllister describes this gaze in her study of internment photography:

33 I find the perspective of participatory action research and participatory photo projects helpful. This keeps the viewer from looking at the photographs with contemporary aesthetics, and forces a consideration of Tom’s lived experiences and choices. While the theory behind this research is far more recent than the internment, Tom demonstrates principles of it in his photographs, and seems to have experienced similar benefits to participants in organized projects. This perspective also aligns with Namiko Kunimoto’s work on family photography, which emphasizes Japanese Canadian family images were transformed by the political conditions of the internment as part of a cycle of “communal experience into personal photographic narrative, and from personal photographic narrative into public historical record” (2004: 131). Before it was theorized, interned Japanese Canadians were performing participatory research: their photography functioned as a way for people to understand and cope with difficulty, and later helped define the public’s understanding of the events.

34 Participatory photography research is a process where members of marginalized communities are given access to image making tools, and assisted in the act of documenting their own lives. The roots of the practice began in healthcare, but the practice has spread as technology becomes cheaper and easier to use. Projects take place across the globe, with, for example, members of indigenous groups, people experiencing poverty, those living with stigmatized diseases such as HIV/AIDS, children and adolescents, and people in rural areas (Bau 2015: 75-77). Valentina Bau notes the power of these projects lies in the images: “within discussions engendered by images … communities find the tools to rebuild and/or transform themselves” (76). The aims of most participatory photography projects are to create, or at least inspire, social change in some way. As Gloria Johnston summarizes, participants in participatory photography projects explore issues relevant to their communities and daily lives by “taking photographs, discussing the photographs, developing narratives of the photos and participating in social action to enact social or policy change” (2016: 801).

35 I recognize using a research process developed in the 1990s to frame a discussion about photographs taken in the 1940s is anachronistic. However, I cannot escape the parallels between Tom’s actions and those of a participatory photography practitioner. Tom, a member of a marginalized community, took photos documenting his daily life, discussed the photos and developed narratives, and finally, was an integral part of a large scale archival effort to ensure memories of the internment are preserved for future generations.

Tom’s Life Story

36 Tom’s parents were both Japanese-born and immigrated to Canada in the early part of the 20th century. His father came first, and sent back letters to Japan to be matched with a Japanese wife. Tom’s parents both moved to Vancouver and, by 1923, had established themselves reasonably well. Tom was born in 1927. His parents and growing family shared a house on Powell Street with other extended family members. As Tom notes, they even owned a Model T Ford car:

37 Tom’s father was a carpenter at a lumber mill. Making was part of the family’s life:

38 Eventually, Tom’s father started a successful bicycle shop in the Powell Street neighbourhood. Tom describes the family’s journey through entrepreneurship:

39 While the family experienced success relative to other immigrant families at the time, they still experienced the same brutal discrimination faced by other Asian families in Vancouver:

40 He told me this story twice, during each of our interviews. It came without prompting and floored me each time. It is difficult to fully convey how his demeanour changed when he told the story, but something about the way in which he held an imaginary baseball bat and the tone in his voice vividly evoked the fear he must have felt as a young boy.

41 Eventually, Tom and his four brothers, two sisters and their mother, like all other Japanese Canadians, were forced to leave their home, their store, and their possessions behind and move into the interior of British Columbia. Since they had more income and resources, they chose to go to self-supporting camp, where Tom and his family managed the cost of their internment. This choice reflected their status within the Japanese Canadian community at the time. The losses the family experienced were nonetheless significant, as Tom describes:

42 So … what I feel very badly, is for these older, well the immigrants, first. Because they, like my father came in in 1908, and a lot of them worked hard, till 1942, establishing themselves. Businesses, buying houses, and so on. Buying cars. Then all of a sudden, all of that’s seized. So, like my brother and my mother worked hard on the business, and all of a sudden, as I showed you before, that house was sold for 1500 and whatever, 70 dollars or something, with the 75 dollars’ broker’s fee, and then it had to be split between, because it was built between the two brothers. And\ the store, well the stock, not very many bicycle businesses even today. So, the stock was confiscated, and that was sold for next to nothing. My mother never told me how much. The car, we had got the car, in 1936, it was 1942. They assessed it at 100 dollars, plus, after they took all the service charges, it was worth nothing. And so, I felt sorry for my brother and my mother who worked so hard to support the family and they lost everything. Whereas, the younger ones, like myself, and my younger sister, we came to Toronto, and finished off our schooling. So, we didn’t feel the loss as much, because we didn’t have anything when we were younger. Whereas the older people, the Isseis, the immigrants that came, they lost everything (Matsui, August 11, 2015).

43 Tom was a generous interviewer, but had his boundaries. He would share stories like the ones I have included, which were challenging, beautiful, touching, hard, and fascinating to listen to, and abruptly break for lunch because he noticed the time. It was important to him to fully participate in the community of life at the Cultural Centre on his volunteer days. So, with my head full of his difficulties, I would then join him with his fellow volunteers around the communal table at the Centre, and listen to them talk about their grandchildren, vacations, and new homes. More than any questions or narratives could do, this experience reinforced the importance of considering Tom’s life story as one that was complex, nuanced, and full. Tom Matsui was far more than his internment story.

Tom’s Memories of Making a New Life in Lillooet, British Columbia

44 People in self-supporting camps could take more with them than typical government internees, and were subject to fewer restrictions than those in government camps, but conditions were still difficult. Tom recalls having to assist in building his family’s home since he was a young, able-bodied male, but too young to be sent to a road camp. Building homes was a common first act of creation, as there were not many places in rural British Columbia that could accommodate the sudden influx of people the internment caused. Homes were very simple and terribly insulated, which was a problem during interior British Columbia’s cold winters. Many families made additions to personalize their living spaces. Tom recalls one made to his Lillooet home to mimic something his father built in Vancouver—a Japanese-style bath:

45 Tom recalled that the Lillooet community banded together to build a school for the children. These narratives were relatively common; Japanese Canadians often built buildings and furniture, scrounged for books and supplies, and found older children or young women to be teachers. In some cases, communities received assistance from church missionaries, but in many narratives that I listened to, communities figured out how to make schools on their own. I have not yet been able to discern whether the frequency of these narratives was because of a focus on education in Japanese Canadian culture, or because most of the older individuals I spoke to in LOI were of school age during the war, and so disruption in schooling was a common experience. Here is Tom’s memory of school building:

46 Making food was one way in which Tom’s family and their community coped with their living situation. They had a lush garden and grew many vegetables:

47 The gardens and their produce were a prime source of inspiration for Tom’s photography. As mentioned, Japanese Canadians were supposed to surrender cameras and radios before they moved, even if going to self-supporting camps. Tom smuggled his personal camera to Lillooet:

48 Tom’s interest in photography had started before he was forced to leave Vancouver. In this excerpt, he describes how the hobby began, and how he developed images in Lillooet:

49 The casual way that he referenced the process of developing makes me smile each time I read it. He was generous, but in a bounded way; somehow, I knew when we were talking I would not get any more information than that about the developing process if I asked further.

Tom’s Images

Display large image of Figure 1

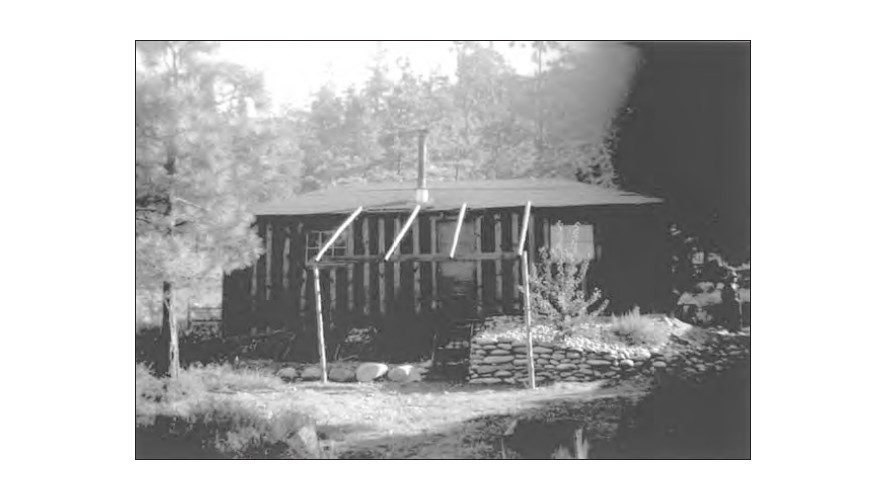

Display large image of Figure 150 I have included eight examples of Tom’s photography. The first (Fig. 1) is of the house Tom and his brothers built for their family. It is a simple square house, like other internment homes. In the image, a viewer can see a wooden frame over the door, a carefully placed line of rocks to the left of the door, and a pile of sandbags on the right. The caption describes it was the only house with a basement in the community; elsewhere in our interview, Tom describes digging out the basement so he would have a place to play ping pong with friends. The image is stark, showing home life as a work in progress. The proud caption, added years later, suggests Tom appreciated and valued what his family could make for themselves. Things were very hard—the house had no insulation and all alterations, such as the porch, were done by the brothers—but they were at least able to make themselves a basement.

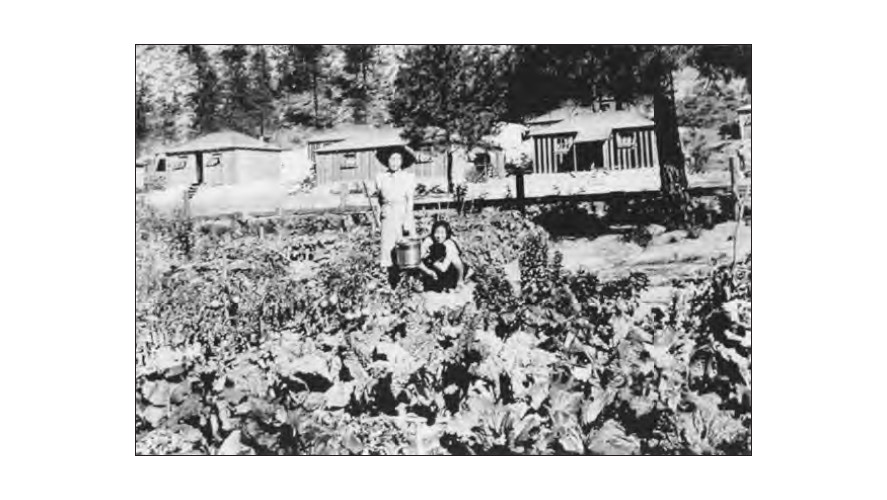

51 The next three images show the way Tom’s family made food from the landscape. The first of this series of images (Fig. 2) shows Tom’s sister, Mary, and his mother, Shizue harvesting from the strip gardens. There is a row of homes in the background, all bearing a strong resemblance to Tom’s family home. The garden seems to be overflowing with plant life, dwarfing the women. It is difficult in the black and white image to know what was edible and what might have been decorative or weed. What is striking is the abundance; as Tom described, the natural state of the land is arid, and to have any plant life, edible, decorative, or weed grow with such energy is reflective of an immense amount of human ingenuity and work.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2 Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3 Display large image of Figure 4

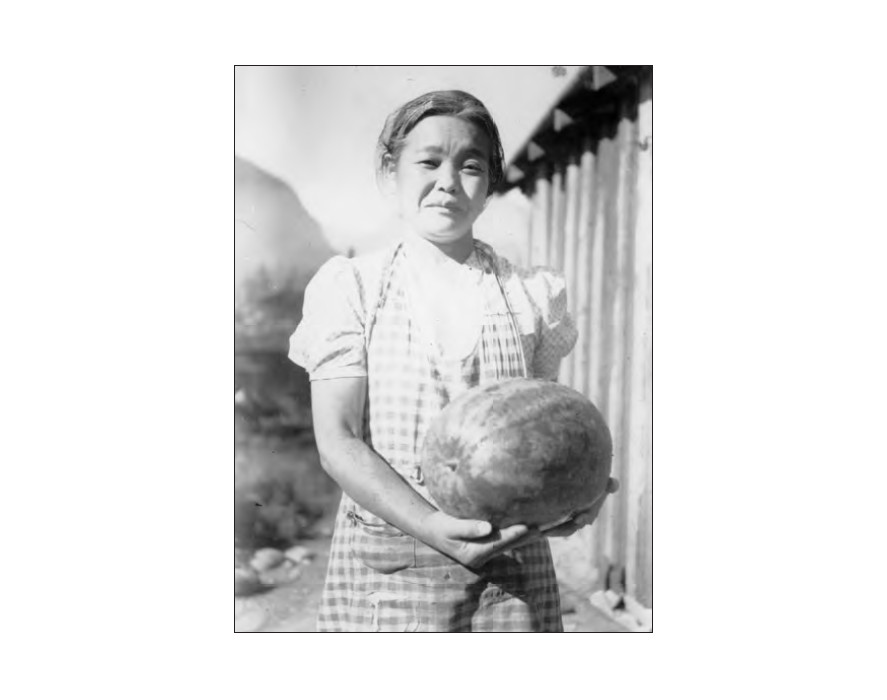

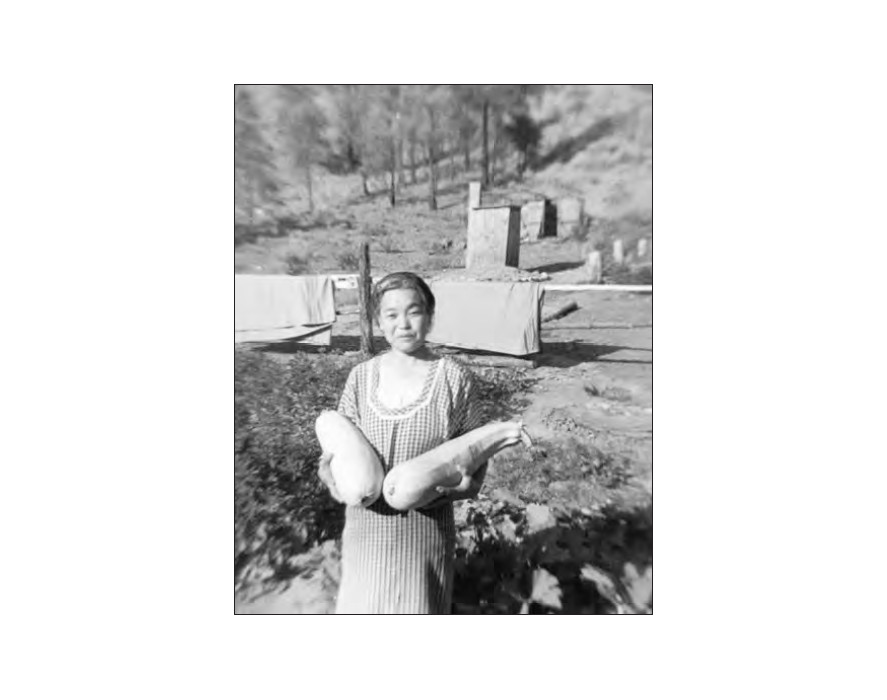

Display large image of Figure 452 There are two images of Tom’s mother, Shizue, with a large watermelon grown in the strip gardens (Fig. 3). In the watermelon image, she stands beside a house, wearing a checkered apron, smiling at the photographer, whom I assume is Tom. The watermelon is large, and as the caption notes, grown because of the warm summers in the valley. In this image, I am struck by Shizue’s face. Her calm gaze and steady hands cradling the melon exude a quiet strength. It is a sensitive portrait. The remaining image, taken the following year, shows Shizue carrying two large squash (Fig. 4). Her gaze is similarly calm, and her body seems steady, despite the weight of the vegetables. This portrait shows a larger view of the family’s garden, and includes an outhouse in the back. In our interviews, Tom talked about the outhouse and how he designed a venting system to mitigate the scents of waste that would cook in the summer sun.

53 In both images, I read a youthful pride in his mother`s skill. Tom had limited photography supplies, and limited time to engage in the craft, so each image represents something Tom felt was important to preserve. Posing his mother with her large vegetables seems almost to be an act of rebellion. Tom is celebrating his mother as a creator, able to provide food for her children in the difficult landscape. In the images, Tom seems to be recognizing that she was not only providing for the family, but creating a thriving world. They reference images that, in other circumstances, might represent winners at county fairs where bounty and growth are highlighted. Tom showed me the images of his mother and the watermelon and his mother and the squash during both interviews, and smiled proudly as he pulled them out.

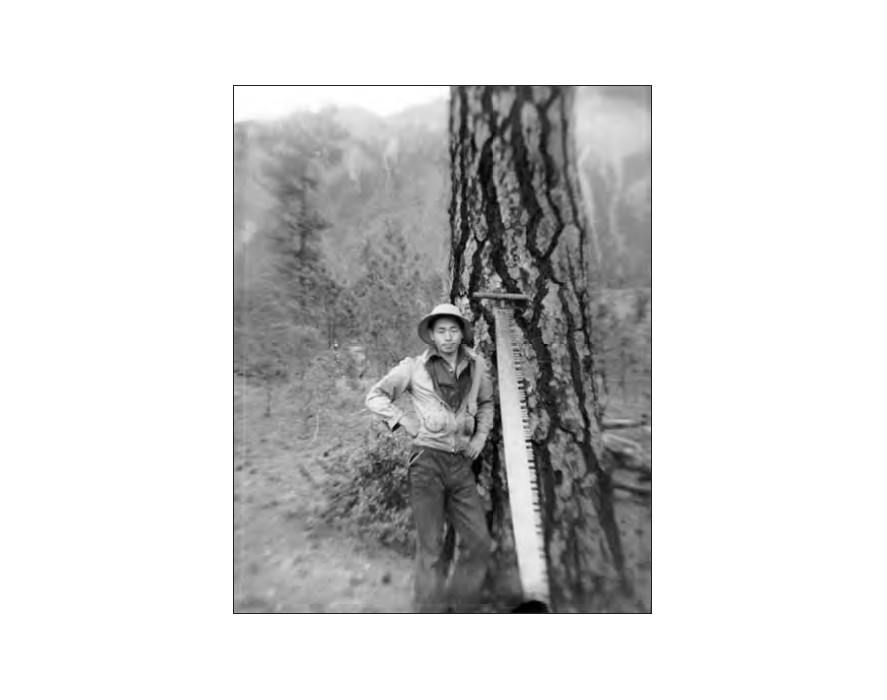

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 554 Another portrait in Tom’s collection shows his brother, Dick, with a large firewood saw (Fig. 5). Dick casually leans up against the tree in the portrait, gazing back at the photographer. One common job for Tom and his brothers in the camp was to cut firewood so the family would have heat in the wintertime as the poorly insulated house could get quite cold. There is a confidence in Dick’s pose, and an ease that reveals a familiarity with the tool beside him. At the time the photograph was taken, the family had been in Lillooet for a year, but Dick gazes assuredly at his brother. He knows how to handle the saw, and how to make firewood.

Display large image of Figure 6

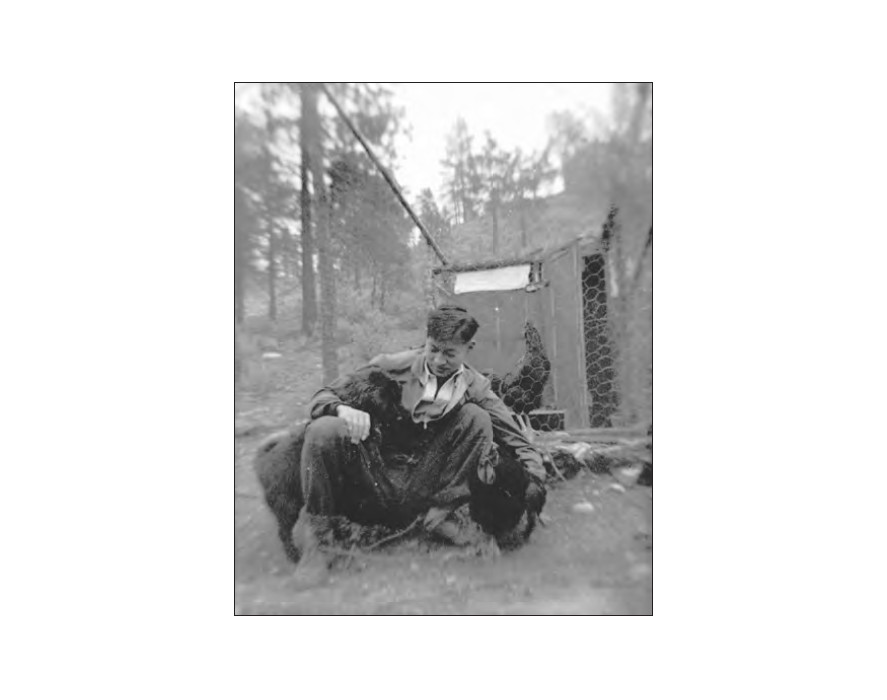

Display large image of Figure 655 Tom does not appear often in his photograph collection from Lillooet. There is an image of Tom and his brother cutting firewood, Tom eating lunch after cutting firewood, Tom apple picking in a nearby community (which he did to help earn money to support the family’s life in Lillooet), and Tom and the family dog and some chickens in a homemade coop. I have included the image of Tom and the chickens and dog, as it shows yet another instance of making done by the family in the creation of a regular source of protein (chickens and eggs) and the necessary carpentry required to house that protein (the coop) (Fig. 6).

Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 7 Display large image of Figure 8

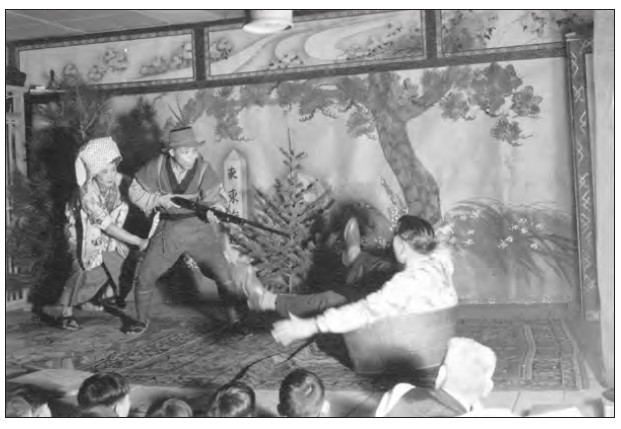

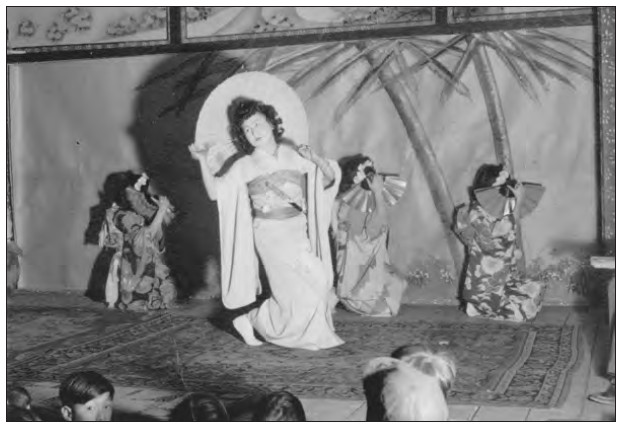

Display large image of Figure 856 The final images are of skits. Devoid of family context, it is more difficult to see deep personal meaning, however, thinking about the images as examples of making that occurred in Lillooet, they provide evidence of considerable art making and community building. The first seems to be a scene from a play (Fig. 7), and the second, from a traditional dance performance (Fig. 8). There is a painted backdrop in both images, and costumes and props have obviously been assembled or made from scratch. In both images, I love the spectators’ heads in the foreground; their closeness to the stage parallels the closeness of their living conditions. The photos are dated from winter of 1946. By then, the community at Lillooet was established enough to develop more sophisticated forms of recreation. Necessities of water, shelter and food were present in some form, and theatrical performances were then developed to provide entertainment for the community. Thinking about Tom, the fact that he chose to use some of his limited supplies to document them suggests that the performances were a source of joy, at least for him.

Tom Making History

57 Tom’s photographs from Lillooet reveal the experience of internment through the eyes of a teenager. He photographs his family going about their daily work, and as recreation develops, he photographs plays and swimming trips (visible in the complete collection, available online at the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre). They are images that reveal considerable amounts of making, when the viewer is aware of even a rudimentary version of the internment history.

58 Kristen McAllister noted a division in narratives about the internment among Japanese Canadians in her research that is important to consider with respect to Tom’s photographs:

59 Taken simply, Tom’s photos could be a representation of the first sort of history that McAllister discusses: the nostalgic, happy time. Proud photos that demonstrate skill with gardening, home building, and lumber work, paired with photos of plays seem to add an air of nostalgia to Tom’s internment story. However, when you consider the photos as acts of history-making created in the camp by a 15-year-old with a smuggled camera, they take on a different tone. They can be, I suggest, a precursor of contemporary participatory photography research: a radical act of documentation.

60 When asked why he took photos, Tom described photography as a hobby, something he enjoyed. But here, it is important to recall that Tom not only smuggled a camera into the internment camp and took photos he developed in his bed at night, but he made sure the photos came with him to Ontario when he moved. He preserved them in his home for more than fifty years, and in a final act of heritage, scanned, catalogued, and captioned them to donate to the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre. The captions are a fascinating addition. Namiko Kunimoto suggests the organization of photographs into albums “offered a sense of control over the newly imposed physical domain” created by the internment. I suggest that these captions were, for Tom, a way of maintaining control over his history, which had been forever altered by the war.

61 Looking at the photos as artifacts created in the moment, the images show Tom coming to understand what’s happening, and wanting to highlight the talents of his family and community in creating life in Lillooet. In Tom’s decisions to carry the images to Ontario and keep them until his 80s, it is possible to read a greater resistance to the internment through this desire to maintain narrative control. He also worked in his later years to ensure the stories would not be forgotten, creating an archival collection at the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre that includes photographs from Lillooet, as well as a series of documents and photographs relating to his later life as a proud Japanese Canadian. In Tom’s collection, there are images of internment reunions, pamphlets and letters relating to the Redress apology that Japanese Canadians received from the government in 1988, and even a photograph of Tom`s cheque from the Government of Canada for $21,000. This collection is the work of a man told in his youth that his life was unimportant. However, through the photographs he compiled in an act of non-violent protest, he defiantly showed evidence of a full, rich life.

62 I asked Tom why he felt compelled to share his experiences now, after so many years. In the interview where I asked this, his first response makes what I can only see as a difficult allusion to the Holocaust, comparing the experiences of Japanese Canadians to that of Jewish people in Europe. Knowing him, even a little, I appreciate that he was making a blunt allusion to convey a meaning, yet the comparison is still shocking. He then went on to share the following thoughts about the importance of remembering the internment events:

63 After this comment, the interview continued into a discussion about grocery stores, teaching, and his family. It is a wide ranging few minutes that conveys Tom’s anger and his beliefs about the importance of memory, as well as the fact that, again, he is more than his internment story and feels comfortable in his current life in Toronto. We finished the interview and signed some forms, and Tom went back to the archival group’s regular meeting.

64 Tom has, in these last thoughts and actions from our first interview, hit upon a suggestion Johnson makes about participatory photo projects: that projects should be “policy informing rather than policy changing” (2016: 808). Tom recognizes the archival group’s efforts and his own photographs are not world changing in and\ of themselves, but taken together as a collection, they are a powerful repository of memory which have the potential to remind future generations that, as he says, “tolerance is one of those things you have to have” (Matsui, April 7 2015).

Endings and Future Research

65 Tom Matsui passed away in November 2015. His loss strongly affected members of the archival group at the Centre, as noted in a newsletter tribute from archivist Theressa Takasaki. The group remains active, and there are likely many more stories of making during internment that can be collected within this group alone. I am certain there are rich histories of making within the Japanese Canadian community across the country as well.

66 In a talk entitled “War, Peace and the Folklorist’s Mission,” folklorist Henry Glassie uses the play Waiting for Godot as a metaphor for the experiences of everyday people in times of conflict, arguing that a common perception that it is a play about nothing happening obscures the deeper meaning. He describes Godot as a meditation on the value and strength people can find in time spent sharing stories with friends: “when nothing happens, people have their work, their friends, their old stories. Nothing could be more important.” He suggests the mission of folklorists in dealing with histories of conflict and violence should not be to examine the big parts of history like timelines, armies, or the mechanics of governance, but rather to “acknowledge and celebrate the victory of daily endurance” (2014: 78-79).

67 As people with direct lived experience of the Japanese Canadian internment begin to pass away, collecting personal narratives becomes increasingly important. Their stories about the internment are a reminder of the devastating harms human beings can inflict on each other, and a powerful lesson for all Canadians about tolerance. The specific stories about making in camps and afterwards, both on a large and small scale, raise a powerful question: if people like Tom Matsui and his family did not have to spend their resources re-making their lives after the losses they experienced, what else might they have been engaged in making instead? What contributions to collective society were lost through this forced redirection of making energy? The exact answers are impossible to know, of course. But in light of the evidence of considerable creative energies that people like Tom’s family did expend during the war, our cultural losses are probably more substantial than any of us would like to imagine.

Thanks, most especially, to Tom Matsui, Jeanne Ikeda-Douglas, Emma Nishimura, Aiko and Michael Murakami, and Cheryl Shoji for sharing their stories. Thanks to Dr. Pamela Sugiman and Dr. Jordan Stanger Ross for their support and counsel during my work with LOI. Thanks to Elizabeth Fujita-Kwan and Theressa Takasaki for their warm welcome at the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre. Thanks to the team of oral history research students I worked with during my time at LOI: Eglantina Bacaj-Gondia, Kyla Fitzgerald, Alicia Fong, Peter Hur, Joshua Labove, Elena Kusaka, Alexander Pekic, Momoye Sugiman, and Erin Yaremko. It was wonderful to learn alongside you.