Research Reports

Canary in the Mine and the Concerns of Research Councils, Applied Ethnomusicologists, and Museum Professionals

Abstract:

In this paper, I share the story of an interactive, digital exhibit called Canary in the Mine: Nova Scotia Mining Disasters and Song both to inspire future music-centred exhibits and to offer insights into the experience of a non-museum professional developing an exhibit. I concentrate on the ways in which this exhibit exemplifies a response to pressing concerns of three distinct but similarly invested groups. First, the exhibit is an example of knowledge mobilization, a key concern for research councils and funding agencies that can be approached to fund projects such as Canary in the Mine. Second, the exhibit is an example of applied ethnomusicology, an area of growing interest and activity for many ethnomusicologists who seek to solve concrete problems with music and music knowledge. Finally, the exhibit offers museum professionals a model for using digital technologies to incorporate intangible culture into their institutions, a topic of increasingly pressing significance since UNESCO enacted its Convention for Safeguarding Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2003.

Résumé

Dans cet article, je raconte l’histoire d’une exposition numérique interactive intitulée « Le canari dans la mine : les drames des mineurs de Nouvelle-Écosse en chansons » [Canary in the Mine : Nova Scotia Mining Disasters and Song], tant pour inspirer d’autres expositions centrées sur la musique que pour proposer un aperçu de l’expérience d’une personne ayant conçu une exposition sans appartenir au corps professionnel des musées. Je me concentre sur la façon dont cette exposition constitue un exemple de réponse aux préoccupations pressantes de trois groupes distincts mais tous aussi concernés. Tout d’abord, cette exposition représente un exemple de mobilisation des connaissances, préoccupation essentielle des conseils de recherche et des organismes subventionnaires auxquels il est possible de s’adresser pour financer des projets tels que « Le canari dans la mine ». Deuxièmement, cette exposition constitue un exemple d’ethnomusicologie appliquée, domaine pour lequel de nombreux ethnomusicologues éprouvent de plus en plus d’intérêt et dans lequel ils sont de plus en plus actifs, car ils cherchent à y résoudre des problèmes concrets relatifs à la musique et au savoir musical. Enfin, l’exposition constitue pour les professionnels des musées un modèle d’utilisation des technologies numériques permettant d’intégrer la culture immatérielle à leurs institutions, domaine qui prend une importance croissante et pressante depuis la promulgation, par l’UNESCO, de la Convention pour la sauvegarde du patrimoine culturel immatériel en 2003.

Down the shaft underground in our usual way.

In the Cumberland pit how the rafters crashed down

And the black hell closed ’round us way down in the ground.

Now when the news reached our good neighbors nearby,

The rescue work started; our hopes were still high.

But the last bit of hope like our lamps soon burned dim;

In the three-foot high dungeon we joined in a hymn

In that dark, black hole in the ground.

The men had gone down where the dust was adrift

Though fortune was theirs to be on the payroll

They were given no warning of what would unfold

Did they hear it explode? Did they see the flash?

Did they suffer long before they breathed their last?

An act of God or was it methane gas?

But something ignited the blast.

1 The stanzas above come from two Nova Scotia coal mining disaster songs. “Springhill Disaster” was initially composed by Maurice Ruddick (and later modified, recorded, and released, with Ruddick’s permission, by Bill Clifton and His Dixie Mountain Boys). Ruddick was a miner who miraculously survived more than a week before finally being rescued after a “bump” killed seventy-five miners on Oct 23, 1958. “Pictou County Mining Disaster” was composed by Al Hanis, a singer-songwriter from Manitoba who was living in Vancouver at the time that an explosion killed 26 miners in the Westray mine in 1992. Both songs are featured in an interactive, digital museum exhibit that I curated and developed, entitled Canary in the Mine: Nova Scotia Mining Disasters and Song currently touring various provincial mining, industrial, and local history museums.

2 Both the Springhill and Westray mines were located on the Foord seam, a notoriously unstable but rich coal seam. Springhill suffered multiple disasters and its mines closed permanently after the last in 1958. A “bump” is a geological shift caused by mining activities. Some bumps are minor. In this case, however, the shift was dramatic and fatal: the floor and ceiling of the mine came together, crushing everything in between. At the time of the bump, 174 men were in the mine—75 died. Most of the survivors were rescued within 24 hours. But what makes the Springhill ’58 disaster so famous is that 19 miners survived underground for a week and more. Rescue efforts were severely hampered by extensive damage to the mine structure, making it difficult and dangerous to reach portions of the mine where miners had been known to be working at the time of the bump. Although mining officials and the media reported that there was little hope of finding survivors after 48 hours, rescue efforts continued until two groups of survivors, a group of twelve and a group of seven, were found. The group of twelve was discovered six days after the disaster and brought to the surface the next day. The group of seven was discovered three days later and brought to the surface that same day—nine days after the disaster. Among the rescued miners in the group of seven was Maurice Ruddick, known locally as “the singing miner.” Upon being brought to the surface, Ruddick was apparently asked by a reporter for a song, in response to which he gave a widely-publicized quip: “Give me a drink of water and I’ll give you a song.” Ruddick’s own song about the disaster, as well as two songs by his daughter, Val MacDonald, are included in the Canary in the Mine exhibit.

3 Thirty-four years later and 150 km away in Plymouth, Nova Scotia, on May 9, 1992, an explosion in the Westray mine killed all 26 miners working at the time. Westray had been open less than a year when the explosion occurred. At a time when most mines were closing, the province was de-industrializing, and there was considerable economic uncertainty in the province, the Westray mine had been heralded as an economic saviour. Sadly, in an effort to maximize profits, safety was consistently compromised. The provincial inquiry lists a litany of safety abuses, concluding:

4 The mine’s safety failures came as a surprise to those outside of the immediate community; just a month before the disaster, the Canadian Institute of Mining, Metallurgy and Petroleum honoured Westray with the John T. Ryan Award as Canada’s safest mine. However, it turned out that it won the award by manipulating accident statistics and keeping injured men on the payroll (Jobb 1998).

5 Four separate investigations were subsequently made into Westray by the Nova Scotia Supreme Court, the Nova Scotia Department of Labour, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), and Curragh Incorporated (the company that owned the Westray mine). The RCMP eventually charged Curragh Incorporated and two mine managers with criminal negligence and manslaughter although the charges were later dropped. In response to recommendations in the provincial inquiry, Bill C-45, known as the “Westray Bill,” was drafted and passed, allowing corporations to be held accountable for acts of criminal negligence. The entire fiasco received extensive national and international coverage, no doubt helping to inspire many of the more than two dozen Westray songs in my collection. There are likely many more: when interviewing Jack O’Donnell, conductor of the Men of the Deeps, North America’s only coal miners choir, he told me that he must have received about fifty Westray songs from people offering them to his choir to sing (personal communication January 16, 2014).

6 In 2009, I was invited to collaborate with a disaster sociologist, Joe Scanlon (Carleton University, Ottawa), on a project investigating the representation of disasters in Atlantic Canadian songs. We collected more than five hundred. Assuming that the golden era of disaster songs had long since passed, I started by compiling disaster songs that had been documented by earlier song collectors, such as Helen Creighton; Louise Manny; Shannon Ryan and Larry Small; Elisabeth Greenleaf and Grace Mansfield; and, more recently, by Jack O’Donnell. To my surprise, however, I discovered that many more disaster songs had been written since earlier collectors had documented and published their song collections: a lot more.

7 For example, after the Miss Ally, a fishing boat with five crew, went down off the coast of Nova Scotia in 2013, I collected six songs. I collected a similar number of songs after a Cougar Helicopters crash into the Atlantic Ocean in 2009 while travelling from Newfoundland to off-shore oil platforms, killing 17 of 18 on board. While my project focuses specifically on Atlantic Canadian disaster songs, there are, of course, many examples written in response to any number of tragedies around the world. Google “9/11 songs” or “Hurricane Katrina songs” and you’ll find long lists. When I first began drafting this article, the November 13, 2015, Paris attacks had just occurred, with one song having gone viral within 24 hours of the tragedy and another written by a prominent pop star circulating within ten days. A Google video search for “Pulse nightclub song” returns several songs written in response to the Pulse nightclub massacre in Orlando, Florida, in June 2016, as well as the dedication of existing songs to the victims and several “tribute videos” consisting of images set to especially selected songs. The number of disaster songs that continue to be written today tells me that there is something significant about them. They do something for the people who write them and listen to them. As an ethnomusicologist, I’m interested in understanding what it is that they do.

8 In 2010, I developed a project website (disastersongs.ca) that features a significant collection of songs. The website is organized by type of disaster (mining, maritime, other), and then by event. A brief history of each disaster is provided, along with the songs affiliated with it. For each song, the lyrics are provided, a link to a recording of the song (if available), and some information about the songwriter and/or the song (if known). The project website also includes a blog and a document library. Approximately 1,000-1,200 people visit it each month despite virtually no promotion.

9 I decided to develop an exhibit in addition to the website for a few reasons. First, an exhibit would allow me to focus on questions and issues I had identified in my research but that are not prominent on the website. The website’s focus is on the songs and their lyrics; by contrast, an exhibit could focus more on issues and analysis arising from the song collection. Second, by licensing the exhibit, I could include recordings, which I could not always easily do for the website. An online exhibit would result in prohibitive licensing costs for the music involved. Licensing a physical exhibit is more viable because access to the music is controlled and limited; visitors cannot download the music onto their own mobile devices. By featuring song recordings, I could keep the exhibit’s focus on sound rather than on the lyrics alone, as on the website. Third, I could target particular audiences with my choice of host venues.

10 As an ethnomusicologist, I had no prior training in the design or development of museum exhibits. In looking for models, I quickly came to understand how rarely intangible culture, particularly music (as sound), has historically been the focus of museum exhibits, although this has been changing rapidly over the last decade or so (discussed further below). I therefore offer my exhibit in the hopes that it might inspire future music-centred exhibits. My intention is also to offer museum professionals insights into the experience of a non-museum professional developing an exhibit. As I quickly discovered when reviewing relevant literature, museum exhibit scholarship tends to focus on reception (how visitors respond to an exhibit) rather than production. I would like to inspire future collaborations. Such collaborations can benefit both the researcher, as she learns how to translate research for a broader public, and the museum, which gains access to new research. I am particularly interested in reaching professionals and staff at small, local museums that may have extremely limited resources, whether in terms of finances, space, or staffing—the very type of museum for which Canary in the Mine was designed.

11 As a means of focusing this paper, I concentrate on the ways in which Canary in the Mine exemplifies a response to pressing concerns of three distinct but similarly invested groups. First, the exhibit is an example of knowledge mobilization (also known, among other terms, as “broader impacts,” “knowledge exchange,” and “knowledge transfer”), a key concern for research councils and funding agencies that can be approached to fund such projects. Second, the exhibit is an example of applied ethnomusicology, a growing area of interest and activity for many ethnomusicologists interested in solving concrete problems, putting music to use both inside and outside the academy. Finally, the exhibit offers museum professionals a model for using digital technologies to incorporate intangible culture into their institutions, a topic of increasingly pressing significance since UNESCO enacted its Convention for Safeguarding Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2003. The exhibit’s abilities to address these issues simultaneously are significant reasons for its success. 1 Before addressing these three areas of concern, however, it will be useful to describe the content and structure of the exhibit.

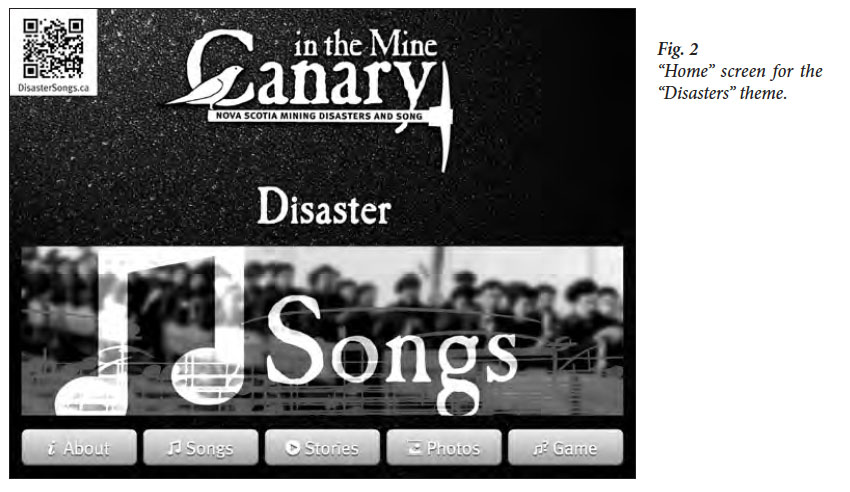

Canary in the Mine: Nova Scotia Mining Disasters and Song

12 The exhibit consists of four tablet computers housed on four custom-designed kiosks (Fig. 1). The kiosks ensure that the tablets are secure (they can’t easily be stolen or manipulated), provide audio access via audio “phone,” and limit distractions while also helping to define the exhibit through consistent imagery and thematic titles. Each of the four kiosk and tablet sets is devoted to a distinct theme. First is “disaster,” which offers a history of mining and mining disasters in Nova Scotia. Songs that document disasters are featured. I also describe typical disaster song characteristics. Second is “home and community,” which is about how disasters affect more than just miners and mining companies, but also families and entire communities, which may rely almost entirely on the mining industry. Third is “mass media,” which is about how many disaster songs are inspired by news coverage in the mass media and also about how disaster songs are disseminated through mass media once composed. Finally, “concerts” is about the increasing importance of benefit concerts after a disaster and the role of memorial concerts on significant anniversary dates after a disaster.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

13 The “home” screen for each tablet includes the theme title and five options: “about,” “songs,” “stories,” “photos,” and “game” (Fig. 2). “Songs” and “stories” vary from theme to theme but “about,” “photos,” and “game” are the same for all four themes. “About” provides a brief overview of the exhibit, a link to educational resource materials, and credits. “Songs” is the heart of the exhibit/ app. Each theme features four-to-six songs that speak in some way to the theme of the kiosk. To create a sense of continuity across the kiosks and themes, songs about two particular disasters are found in each theme: the 1958 Springhill and 1992 Westray coal mining disasters. These two disasters have inspired more songs than just about any other disaster. However, songs about other mining disasters are also included.

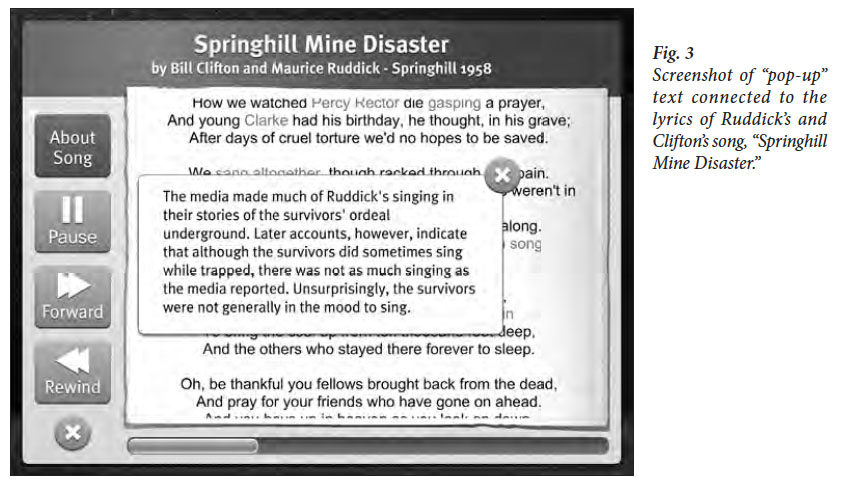

14 Some of the most useful advice I heard when I began designing the exhibit was to plan for three basic categories of museum visitors: the scholar, the stroller, and the streaker (I learned these categories informally in discussions with museum professionals, but categories of museum visitors are frequently discussed in the literature; see, for example, Kelly 2009). Scholars like to read everything, strollers engage with a little of this and a little of that, and streakers move through a museum quickly, doing little more than looking to their left and right as they walk through an exhibit. I had to consider how my exhibit could be meaningful for each of these visitor types. I therefore developed the exhibit knowing that text had to be presented in bite-sized chunks in a non-linear fashion (this was perhaps the most difficult challenge for me as a scholar used to writing lengthy, detailed, and sometimes obtuse arguments in a very linear manner), and recognizing that not everyone would read every piece of information or read them in the same order. So once a particular song is selected, the visitor is presented with lyrics as the song begins to play. Clickable text appears in red. The visitor is invited to touch red lyrics to see a “pop-up” message that offers a very brief insight (usually less than fifty words) into the disaster, the song, the songwriter, and/or the theme of the kiosk (Fig. 3). Ideally, the visitor gradually develops insights into, and understanding of, the kiosk theme and disaster songs more generally.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3

15 The app developers suggested that narration might help to provide an engaging framework for the exhibit. I turned to a local playwright for help. Scott Sharplin developed two fictional characters, each of whom has short monologues for each of the four themes (less than two minutes each). The monologues speak to the issues of the theme in question. The first character, Joe MacPhee, is a retired coal miner who was hurt in the 1956 Springhill mining disaster. He was witness to both the 1958 Springhill and 1992 Westray disasters. Gillian Long is a singer-songwriter born the day the Westray disaster occurred. She discovers Nova Scotia’s mining history and disaster songs through her songwriting activities.

16 Although the monologues are short, they are long enough that they required visuals to keep visitors engaged while listening. I therefore worked with various archives and libraries to identify and include historical photographs of Nova Scotia mining disasters. The photographs allowed me to include images from more disasters and from more areas in the province than represented in the exhibit’s songs and were therefore a valuable addition. They offer historical data that enrich the fictional monologues.

17 The “photos” section is a gallery of photographs from the monologues for anyone who doesn’t want to listen through all the monologues or who has a particular interest in images. The photographs are grouped by region in the province, and they are the same on all four kiosks.

18 Finally, there is an interactive component. The game was particularly challenging to conceive. I had wanted to include interactive songwriting activities. For example, I wanted to ask visitors to add a verse to an existing song, or to crowd-write a song, or simply to replace the details of one disaster song with the details of another better known to the visitor. However, the app developers warned me that some people, particularly youth, find it amusing to enter inappropriate text when the opportunity arises. They suggested that I avoid allowing textual input of any kind.

19 It was difficult to conceive of an activity that was both respectful and relevant without being condescending. Ultimately, we developed a game in which excerpts from disaster songs are played and the visitor has to identify which of the four exhibit themes is being articulated. A random selection of excerpts is generated upon each iteration of the game, and there is a substantial bank of excerpts. The game (and the bank of song excerpts) is the same on all four kiosks.

20 If I could, I would make the exhibit available virtually on the disastersongs.ca website to make it accessible to anyone interested, but there are good reasons to make the exhibit available physically in museums rather than online, aside from the issue of licensing costs mentioned earlier. First, when museums are organized around particular themes or topics such as mining, visitors will find—and engage with—exhibits. While an online exhibit would theoretically be more accessible to anyone interested, the sheer size of the World Wide Web can make it difficult for people to find particular projects, especially if they don’t know to look for them. Visitors have also set aside time for a museum visit, so there is greater certainty that they will take time to explore an exhibit than they might if they came across the same exhibit online. Finally, there is a greater likelihood of social interaction when visiting an exhibit in a physical museum than online. Falk and Dierking argue that social interaction in a museum—interacting with one’s companions as well as with other visitors and museum staff—is a key component of the museum experience for visitors (2013).

Venues: Institutions Hosting Canary in the Mine

21 At the time of writing, Canary in the Mine has been hosted by five different institutions or organizations in Nova Scotia: the Cape Breton University Art Gallery (June 12-August 21, 2015); Oceanview Education Centre, a middle school in Glace Bay (March 2016); the Museum of Industry, New Glasgow (April 12-June 12, 2016); the Glace Bay Miners’ Museum (July-October 2016); and the Cape Breton Centre for Heritage and Science, Sydney (December 2016-June 2017). The CBU Art Gallery was the first to host the exhibit since it was the most appropriate on-campus venue through which to share my project with faculty and students. Oceanview Education Centre was invited to host the exhibit for two weeks during the winter off-season, when most provincial museums are closed, in order to maximize its use and value. My intention is that Canary in the Mine will be hosted by a number of other small industrial, mining, and/or local museums located throughout the province over the coming years. While the CBU Art Gallery, Museum of Industry, and Cape Breton Centre for Heritage and Science have dedicated spaces (of varying sizes and configurations) available for temporary exhibits, the other venues do not. In all cases, the kiosks’ placement was determined mostly by proximity to electrical outlets, required to power the tablets.

22 Unfortunately, due in part to the limited capacity of each organization to measure and evaluate reception, I am unable to provide a detailed description or analysis of visitor responses to the exhibit. Neither does the Canary in the Mine app include a component designed to measure visitor engagement (e.g., length of time spent with the app, length of time spent on individual sections of the exhibit, etc.), mostly due to budgetary limitations and a lack of forethought on my part.

23 However, I did write to staff at hosting organizations to ask about the exhibit’s reception. Overall, responses indicate that the exhibit has been well received:

24 Respondents did, however, recommend some ways that the exhibit could be improved, suggesting that a reduction of the exhibit’s weight and size would make transportation easier and cheaper. Another suggestion was that making the kiosks usable from a seated position would encourage longer engagement. Respondents also noted that having a means of documenting visitor usage in the app would also have been useful.

Current Issues in Funded Research: Disseminating and Applying Knowledge

25 Canary in the Mine was funded by an outreach grant by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC), a federally-funded research granting organization. SSHRC, like research councils all over the world, now requires a section on knowledge mobilization (KMb) in all of its grant applications. Each country has its own preferred term (“broader impacts” in the U.S. and “knowledge transfer” or “knowledge exchange” in the U.K., for example), although they are all similar in their goals. The increasing demand for KMb has given rise to specialized staff, entire university departments, and KMb organizations dedicated to helping faculty to develop KMb plans.2

26 Knowledge mobilization “is about ensuring that all citizens benefit from publicly funded research.”3 SSHRC defines KMb as “the reciprocal and complementary flow and uptake of research knowledge between researchers, knowledge brokers and knowledge users—both within and beyond academia—in such a way that may benefit users and create positive impacts within Canada and/or internationally, and, ultimately, has the potential to enhance the profile, reach and impact of social sciences and humanities research.”4 It is no longer enough for scholars to present papers at academic conferences or publish articles in peer-reviewed journals, although these outcomes are still expected. Increasingly, academics are being asked to disseminate their research broadly and, in the process, explain or demonstrate its significance. They are also being asked to show how other individuals and organizations can benefit from particular research.

27 Drawing from SSHRC’s guidelines for effective knowledge mobilization,5 ResearchImpact, a network of eleven Canadian universities whose goal is to maximize the research impact of scholars (http://researchimpact.ca/), presents four domains of knowledge mobilization: 1. co-creation (co-development of activities, and products); 2. brokering (connecting organizations, individuals or other partners); 3. exchange (the reciprocal sharing of research through activities such as conferences, social media and the training of students); and 4. dissemination (the one-way dissemination of research through any number of means, including academic publications but also blogs, websites, videos, and exhibits).6

28 The Canary in the Mine exhibit clearly falls into the “dissemination” category. However, there are aspects of the other categories inherent in the project as well. The exhibit, while ultimately my responsibility, was co-created through the involvement and contributions of many partners. For example, song composers gave me permission to include their songs, allowed me to interview them, and reviewed the content pertaining to their songs. Playwright Scott Sharplin developed the two exhibit characters and their monologues and oversaw the actors who recorded them. Local archives and libraries provided historical photographs for the monologues. An internationally respected education consultant developed the educational guide for Nova Scotia music teachers (freely available on the disastersongs.ca website). The app developers provided invaluable direction on the development of an app that would work effectively and be engaging.

29 The exhibit also plays a brokering role in that it is designed to attract local residents back to museums they may not otherwise visit due to the museums’ static content. The educational guide is designed to inspire music and social science teachers to bring their students to the exhibit and to integrate the exhibit’s content and lessons into their curricula.

30 In terms of “exchange,” a graduate student assisted me with the exhibit7 and several undergraduate students worked on the associated website, and I have a Twitter account that was initially created specifically to share disaster songs research. The exhibit played a role in inspiring the theme of “exhibiting music” for the annual conference of the Canadian Society for Traditional Music when it was hosted at my institution, Cape Breton University, in June 2015, and I have presented workshops on the exhibit. The project website, disastersongs.ca, offers a clear example of exchange, as comment fields allow visitors to respond to content, and several people have written to me privately after having discovered the website to let me know about songs not already included in the site.

31 Projects able to address more than one domain, like Canary in the Mine, fulfill research councils’ and granting agencies’ expectations for academic KMb. Museums can offer well-developed pathways to KMb for academics. In return, scholars can offer museums new research and access to funding not otherwise available to them.

Current Issues in Ethnomusicology: Applied Ethnomusicology

32 The Society for Ethnomusicology defines applied ethnomusicology as “work in ethnomusicology that puts music to use in a variety of contexts, academic and otherwise.”8 The International Council for Traditional Music defines applied ethnomusicology as “the approach guided by principles of social responsibility, which extends the usual academic goal of broadening and deepening knowledge and understanding toward solving concrete problems and toward working both inside and beyond typical academic contexts.”9 In both definitions, the emphasis is on using music, or ethnomusicological knowledge, outside of conventional academic uses (e.g., academic publications and conventional university classrooms).

33 These definitions are clearly consistent with the concept of knowledge mobilization. However, as ICTM’s definition makes clear, whereas knowledge mobilization is specifically about the dissemination of research knowledge, applied ethnomusicology can refer to far more than KMb. Thinking of museums, we might ask what concrete problems do museums face that applied ethnomusicologists might help to solve?

34 Numerous scholars have noted that applied ethnomusicology is not particularly new (e.g., Sheehy 1992; Averill 2003; Dirksen 2012). As Sheehy asks, “What ethnomusicologist has never gone out of his or her way to act for the benefit of an informant or a community they have studied? Are teaching and writing not ways of applying ethnomusicological knowledge?” (Sheehy 1992: 323). But for Sheehy, applied ethnomusicology requires a conscious practice that goes beyond the study of the musics of the world’s peoples to address the question, “to what end”? Klisala Harrison suggests that a second wave of applied ethnomusicology can be identified at present. Whereas the first wave, inspired by public folklore, tended to focus on “ethnomusicology in the public interest” (Harrison 2014: 17), the second wave is broader in its scope and includes projects both within as well as outside the academy, particularly projects that aim to “solve concrete problems affecting people and communities” (18). The assumption often is that public folklore, and by extension early applied ethnomusicology, was about disseminating folklore and ethnomusicological research through museums and similar state apparatuses. Such institutions help to ensure that research doesn’t remain stuck in the ivory tower but instead reaches the average citizen. In some ways, Canary in the Mine is just such a “public” or “applied” research project. However, I think that it goes beyond using museums as conduits for disseminating knowledge and instead serves to meet a particular challenge faced by many small, local museums designed around permanent, static exhibits.

35 I conceived of Canary in the Mine initially as a response to my own concrete problem: how can I get my research out to as broad an audience as possible? In the parlance of Canadian funding agencies, how can I mobilize my knowledge? I wanted to do more than just showcase individual songs and songwriters; I wanted to offer my more theoretical insights to a lay audience. The disaster songs project website offers one means of doing so, particularly via its blog. However, I felt that I could reach a different and perhaps larger audience, one that had self-identified as having an interest in mining history and culture, by developing an exhibit.

36 My initial motivation could therefore be viewed as self-serving. But it also comes from my personal philosophy as a scholar that my research should be available to the public that pays for it (through my state-subsidized salary and state-funded research grants). In this sense, I see myself as a “public intellectual” in ethnomusicologist Gage Averill’s sense (2003).

37 I knew that my research would be of particular interest in Nova Scotia, the Atlantic Canadian province with the most substantial mining industry and, consequently, the most mining-related disasters. It is also the province from which all the mining disaster songs in my collection come. It is a relevant topic in a province struggling to address its post-industrial reality. Given that there were no underground coal mines operating in Nova Scotia between 2001 and today—as this article was going to print, a small, new coal mine opened in Donkin (near Glace Bay in Cape Breton) in March 2017—former coal mining communities, along with the museums that document and represent their history and culture, are facing the challenge of redefining themselves in their post-industrial present. Drawing on Hunt and Seitel (1985), museologist Christina Kreps argues that, “when culture is integrated into development, it can enable the bearers of traditional culture to adapt their ideas and actions to a changing environment within the context of their own cultures and on their own terms” (2003: 13). In other words, for Kreps, the documentation, valuation, and (re)presentation of a full range of culture—both tangible and intangible—is essential for human survival (13). Museums clearly have a role to play in making culture available for integration in development efforts. A shift toward cultural conservation (and away from an earlier model of heritage preservation) among museums is allowing museum staff to take on a leadership role in the task of protecting not just cultural “outputs” or “products” but the very processes that produce them.

38 Folklorist Mary Hufford writes that “a central task of cultural conservation is to discover the full range of resources people use to construct and sustain their cultures (1994: 4). To discover the full range of resources people use to construct and sustain industrial cultures, including Nova Scotia’s mining culture, particularly in a post-industrial context, museums must encompass both intangible and tangible culture in their exhibits and mandates. Canary in the Mine offers one small contribution to this larger project.

39 In considering the institutions that might host Canary in the Mine, I immediately thought of mining museums, industry and trade museums, and small, local museums. What most of these museums have in common is that they are seasonal museums (most are open some time between May and October, during prime tourist season) and only one of the eight initially approached has room designated for temporary exhibits. Such museums find it difficult to motivate local residents to return to the museum after one or two visits; in featuring only permanent exhibits, there is little reason for local residents to return. These small museums also tend to struggle financially; even if they had the room to host a temporary exhibit, would they have the resources to develop one or to pay for a travelling exhibit?

40 With my access to research funding, I realized that I could provide an exhibit for little cost to these museums. In return, my research would reach a broader audience. However, my next challenge was determining how to design an exhibit that could be accommodated in very different physical configurations. Some museums have very little free floor or wall space. I initially conceived of the exhibit in fairly conventional terms and immediately encountered logistical problems. How could I develop panels of text and images that could be accommodated in different physical configurations? Given the limited wall space available, would the exhibit panels have to be suspended from the ceiling or make use of stands? How could sound be made available in these circumstances and how could I ensure the centrality of sound rather than text or objects?

41 It wasn’t until I saw an unrelated exhibit that made use of tablets that I realized that digital technologies could solve several problems. First, tablets are small enough that almost any museum could accommodate them. Even accounting for the kiosks that house them, Canary in the Mine only takes up 12 square feet of space (1.1 sq. m). Second, by developing a virtual exhibit rather than a physical one, I would reduce transportation charges (there’s no need to hire specialist moving companies to move precious historical materials, no need to make arrangements with museums to allow their treasured collections to travel to other sites, nor is there any need to pay for insurance to protect against the loss of priceless objects). Third, digital technologies ensured that sound would remain central to the exhibit. When I was contemplating a more traditional text- and object-oriented exhibit, sound kept becoming “optional,” something that people could choose to listen to or not. The point of Canary in the Mine, however, is that music is at the centre of the exhibit with sound prominently featured.

42 The exhibit not only allows me to disseminate my research findings more broadly, it allows me to help small, local museums to offer new exhibits and therefore attract more visitors with very little cost to the museums in terms of finances, infrastructure, or personnel. In helping to solve a local museum problem, my project remains relevant within my own discipline, as well as addressing the interests of museums and funding agencies.

Current Issues in Museums: Incorporating Intangible Culture

43 Ever since UNESCO adopted the Convention on Safeguarding Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) in 2003, there has been a flurry of scholarship around its implications for museums. One need only search for “intangible cultural heritage” in journals, such as Museum International or Curator, to see the extent to which museum scholars are engaged with this topic. Richard Kurin, the Smithsonian’s Under Secretary for History, Art, and Culture, has been particularly articulate on this topic, arguing that although “museums are generally poor institutions for safeguarding intangible cultural heritage ... there is probably no better institution to do so” (2004: 8).

44 Because the term “intangible cultural heritage” has a particular meaning within the context of the UNESCO Convention, and because I don’t find that the UNESCO definition works particularly well for the content in the Canary in the Mine exhibit, I prefer to use a broader and more neutral term, “intangible culture,” instead. For UNESCO, ICH “thrives on its basis in communities and depends on those whose knowledge of traditions, skills and customs are passed on to the rest of the community, from generation to generation, or to other communities.”10 Moreover, “communities themselves must take part in identifying and defining their intangible cultural heritage: they are the ones who decide which practices are part of their cultural heritage.”11 ICH also has something of a salvage aim: identifying traditions in danger and documenting them for the benefit of future generations (see, for example, Kalay 2007; Alivizatou 2012).

45 Nova Scotia’s mining disaster songs do not fit UNESCO’s definition of ICH. For one, it would be difficult to identify a community that feels a sense of ownership or stewardship of disaster songs as a whole. While we might speak of miners as a community defined by labour, and while it is true that mining disaster songs are often about the miners hurt or killed in disastrous events, the reality is that most disaster songs are not written by miners themselves, or even by others directly affected by a disaster. For example, while it is true that Maurice Ruddick, one of the songwriters quoted at the start of this article, was a miner who survived a disaster, he only wrote his song after being asked to do so by Bill Clifton, who had no prior connection to Ruddick or to Springhill, and it was ultimately Bill Clifton who edited, recorded, and released the song. Al Hanis, meanwhile, was never a miner and never lived anywhere close to the Westray mine disaster he wrote about. He had, however, worked a number of factory jobs and felt a deep sense of grief in response to news of the disaster. I would say that the majority of the songs in my collection of Atlantic Canadian disaster songs were written by songwriters with only a tenuous connection—or no connection at all—to the people affected by the disasters portrayed in their songs. In short, I cannot speak about a clear “community” of disaster songwriters who might offer direction on the appropriate selection and representation of disaster songs.

46 Moreover, there is no sense of disaster songwriting being a skill or even a tradition that is learned or passed on from generation to generation or from community to community. In fact, quite a few of the songwriters I interviewed denied having even heard any disaster songs before writing their own. While consistent patterns across large numbers of disaster songs suggest that songwriters are in fact influenced by other disaster songs, it would seem that such influences have been largely unconscious. In addition, many disaster songs are written by amateur songwriters who tend to have quite limited audiences—their songs are not likely to be performed by anyone other than themselves. There is no particular expectation of preserving or transmitting them to others, other than by sharing them through performance with relatively small audiences.

47 Finally, there is no fear that disaster songs are an endangered tradition that requires safeguarding. As noted above, large numbers of disaster songs continue to be written about very recent events. Since there is increasing media attention being given to the growing number of vernacular memorials created in the aftermath of a tragedy (see, for example, Everett 2002; Santino 2006; Clark 2007; Doss 2008, 2012; Margry and Sánchez Carretero 2011), there is unlikely to be a decline in vernacular responses to tragedy—including songwriting—at any point in the immediate future. Given that disaster songs are not comfortably represented by UNESCO’s concept of “intangible cultural heritage,” I refer to “intangible culture” throughout this article instead.

48 Whatever term we use, museums are faced with the challenge of finding ways to integrate intangible culture into their exhibits and their mandates. Interestingly, even the literature on the incorporation of digital technologies in museums—technologies that facilitate the inclusion and exhibition of intangible culture—has emphasized their use in augmenting visitors’ understanding of built heritage and material culture. To offer just one example, in an article that offers a categorization system for capture technologies (visual, dimensional, locational, and environmental) (Addison 2007), audio is notably absent, underscoring that museums and heritage activists do not often think of sound as part of their purview. There are many other similar examples.

49 It is logical to turn to museums dedicated to music, which are growing in number, to learn from the ways in which they “exhibit” music. Examples of music museums include the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum in Nashville, TN (established 1964); the Rock ‘n’ Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, OH (established 1995); the Experience Music Project in Seattle, WA (established 2000, now the Museum of Popular Culture); the Beatles Story in Liverpool, U.K. (established 2009); the Music Instrument Museum in Phoenix, AZ (established 2010); and the National Music Centre in Calgary, AB (established 2016).12 However, even in these contexts, material and visual culture are often emphasized. For example, Calgary’s National Music Centre proudly proclaims that it is “home to a collection of over 2,000 instruments and artifacts compiled over nearly two decades.” Additionally, it “has also acquired objects and artifacts from organizations across Canada.”13 The Charlie Daniels exhibit at the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum is fairly typical of music-related exhibits, promoted as “featuring musical instruments, stage wear, manuscripts, awards, childhood mementos, and previously unpublished photographs from Daniels’s personal collection.”14 Music, of course, does not exist without material culture. It is also entirely appropriate that a physical space, such as a museum, incorporates physical objects and visual culture. My point, however, is that even in institutions devoted to documenting and celebrating music history and heritage, it can be difficult to focus on intangible sound rather than on material culture.

50 This is not to say, however, that music museums and exhibits are not finding ways to privilege sound. I recently visited the substantial and permanent section of the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, DC, devoted to music. Although much of the area is given over to material culture, augmented by relevant soundtracks playing from speakers set into the floor, two interactive elements stand out for privileging sound. Not coincidentally, they both make use of digital technologies. One element is found in a mock “record store.” A large table with four touch-screen stations in its four quadrants allows visitors to scroll through selected album covers categorized by a variety of musical genres. The visitor can add album track excerpts to a group playlist playing overhead. The playlist also identifies the current track being played. Unfortunately, it can be difficult to hear the tracks because the playlist, despite consisting of short audio track excerpts rather than complete songs, quickly grows so lengthy that it’s unlikely that most visitors get to hear the tracks they selected. The decision to make the sound “public” and social (rather than private by means of headphones or similar technology) means that it can be difficult to hear and to listen attentively. The other element is found in a “recording studio.” This time, two large touch-screen stations are mounted on the wall. Users have five minutes to create their own recording by dragging and dropping various sounds and effects into multiple tracks. In the first instance, visitors encounter historical recordings. In the second, they actually create their own and, in so doing, learn something about the process of creating a musical recording and the impact of recording studios and producers on music history. It is not coincidental that these two components make use of digital technologies in order to focus on musical sound.

51 Surprisingly, given the rapid increase in music-dedicated museums over the past twenty years (note that the majority of the music museums cited above have been established since the mid-1990s) and a growing interest in ICH in museums, music exhibits have received remarkably little attention by museum professionals or in museum journals.15 Meanwhile, literature pertaining to the use of audio in museums is dominated by studies of the use of guided audio tours (e.g., Proctor and Tellis 2003; Smith and Tinio 2008; Lopez et al. 2008; Zimmermann and Lorenz 2008; Simon 2010). Music may not even be present, let alone central, in these audio guided tours. In other words, when audio technology is integrated into the museum, it emphasizes the spoken word or, increasingly, facilitates social (verbal) interaction. Scholarship rarely addresses the abilities of audio technologies to represent and emphasize music as a central subject for exploration in a museum.

52 At the same time that museum professionals are increasingly engaged by ICH, they are studying how to use and integrate new technologies appropriately into their contexts (e.g., Jones-Garmil 1997; Grinter et al. 2002; Sandifer 2003; Din and Hecht 2007; Wyman et al. 2011; Hanko, Lee, and Okeke 2014). As the Canary in the Mine exhibit demonstrates, digital technologies create unique opportunities for “exhibiting” intangible culture within museums. Not only does digital technology offer new means of “displaying” that which is neither concrete nor visible, it can serve to attract and retain visitor attention. Sandifer tells us that technological novelty plays a significant role in holding visitors’ attention (2003). Hanko et al. recommend layering “a variety of digital and technological experiences with more conventional forms of interpretation in any given exhibition” to meet the needs and interests of both technology-seeking visitors and those who are more technologically averse (2014: 8). Gammon and Burch’s research tells us that a digital exhibit should “dovetail with the activity of museum visiting—that is, it does not interfere with visitors’ interactions with other people or exhibits; it is available as soon as it is required and is unobtrusive when it is not needed” (2008: 42).

53 The more conventional and permanent exhibits in the small, local museums that have hosted (or will host) Canary in the Mine can benefit from the novelty of a digital exhibit while providing a valuable social and historical context for understanding the social role of disaster songs. Mining museums feature exhibits on the history and science of mining in the province, while local museums feature exhibits on the history and experiences of local people and communities, which includes mining as well as music and other cultural expressions. Conventional exhibit structures will appeal to those who are, as Hanko et al. call them, technologically-averse. At the same time, Canary in the Mine complements and builds upon these exhibits, deepening visitors’ understanding of local history and culture. Its small physical footprint, digital interface, and audio equipment ensure that it is unobtrusive and will not interfere with other visitors’ enjoyment of the museum’s full range of offerings.

54 In a phone interview (February 16, 2017), Mary Pat Mombourquette, the Director of the Miners’ Museum in Glace Bay, noted the location of the exhibit in the lobby meant that just about everyone who visited the museum spent at least some time with the Canary in the Mine exhibit. The Miners’ Museum offers tours of a mine replica escorted by retired coal miners; visitors engaged with the Canary in the Mine exhibit while either waiting for their tour to start or upon its conclusion, as visitors return to the lobby upon completion of their tour. In addition, people with tickets for a Men of the Deeps concert staged at the Museum engaged with Canary in the Mine while waiting in the lobby for the concert doors to open. For Mombourquette, the inclusion of the exhibit resulted in something greater than the sum of its parts: the exhibit allowed the Museum to diversify its offerings while its content complemented the stories that visitors heard on the tour of the mine. Canary in the Mine also offered a creative, cultural perspective on the scientific and historical information provided in the permanent exhibits.

55 As a digital exhibit, Canary in the Mine is a good example of the integration of digital technologies into the museum, a key consideration for modern institutions. But it offers more than that: it also suggests how such technologies can be used to integrate music and sound, forms of intangible culture—a subject that has rarely been central in exhibits—into the museum.

Conclusions

56 The problems I’m addressing are nothing new: disseminating research to a broad public; helping small, local, and resource-constrained museums to diversify their exhibits in order to (re)attract a local audience; incorporating innovative and interactive technologies into museums; and integrating intangible culture into museum exhibits. But the challenges and potentials presented by digital technology are still relatively new, and the imperatives of KMb and ICH have a newfound urgency as recent public policy has evolved. My intention has been to demonstrate how these “concrete problems,” representing the concerns of various related stakeholders (research councils and funding agencies, ethnomusicologists, and museums), can be mutually addressed by a project such as Canary in the Mine.

57 This article conveys two main messages to museum professionals. The first is to offer the Canary in the Mine exhibit as inspiration for integrating intangible culture broadly speaking, and music in particular, into exhibits by using innovative technologies. The second is to encourage museum professionals to reach out to scholars conducting research in areas relevant to their institutions and offering to support those scholars in the development of an exhibit. In this sense, I am speaking primarily to professionals at small museums who may never have considered collaborating with an academic researcher. I am also speaking from inside a small, primarily undergraduate university, whose faculty would not typically be considered first by museum professionals to approach for project collaboration. Not only do museums offer sites in which to feature research, museum personnel can offer invaluable guidance to academics on the design of effective exhibits while benefitting from access to new research. With research funders’ increasing emphasis on knowledge mobilization, a partnership between museum and academic professionals could be leveraged for funding that might not otherwise be accessible to either on their own. As Falk and Dierking point out:

58 What I am proposing is that partnerships with scholars offer museums not only relevant exhibit research and content, they also exemplify relevance to multiple constituencies simultaneously. Serving the public good can refer to supporting scholars in disseminating their research, as much as it can refer to the broader museum-visiting public. Such partnerships can contribute to a museum’s sustainability by helping it to remain relevant, connected, innovative, current, and financially solvent. Indeed, I echo Falk and Dierking in observing that, for museums to be sustainable and successful in the future, they will need to develop new and creative relationships outside the museum as much as inside it (297).