Articles

Exchanges and Hybridities:

Red Leggings and Rubbaboos in the Fur Trade, 1600s-1800s

Abstract

In the North American fur trade, food and clothing were among the most frequently exchanged material, serving both as necessities of life and expressions of identity. Not only were materials exchanged but new fashions and tastes developed among fur traders and First Nations across North America from the 1600s to the early 1800s. This article examines these two realms of material culture through the link of sensory history, suggesting that they were central to the experiences of the fur trade and indicate patterns of cultural exchange and reciprocity. Dress and diet were key signposts of identity and markers of difference, yet patterns of material exchanges during the expansion of the North American fur trade produced hybrid styles in both clothing and food that were geographically widespread. Examining material culture through a sensory history approach reveals new understandings of the adaptations that shaped the fur trade.

Résumé

À l’époque de la traite des fourrures en Amérique du Nord, les objets matériels les plus fréquemment échangés étaient la nourriture et les vêtements, qui servaient autant aux nécessités de la vie qu’à exprimer une identité. Non seulement ces objets étaient-ils échangés, mais de nouvelles modes et de nouveaux goûts se sont répandus chez les traiteurs de fourrures et les gens des Premières nations à travers l’Amérique du Nord, depuis le XVIIe siècle jusqu’au début du XIXe siècle. Cet article examine ces deux domaines de la culture matérielle au prisme de l’histoire sensorielle, montrant qu’ils étaient essentiels à l’expérience de la traite des fourrures et indiquant des schémas d’échanges culturels et de réciprocité. La coutume vestimentaire et le régime alimentaire étaient des signaux identitaires et des marqueurs de différence, et cependant les schémas d’échanges matériels au cours de l’expansion de la traite des fourrures nord-américaine ont produit des styles hybrides d’habillement et de nourriture qui ont connu une grande extension géographique. Approcher la culture matérielle au moyen de l’histoire sensorielle permet de révéler de nouvelles compréhensions des adaptations qui ont façonné la traite des fourrures.

1 When sixteen Dene visited fur trader James Porter on Slave Lake at the outset of the 19th century, they traded a large quantity of furs and fresh meat in exchange for goods and clothing. Porter’s brief journal entry details one item in particular, “a Compleat [sic] Suit of Regimentals” that was given specifically to honour the chief.1 Gifting special clothing with overt status symbols to Indigenous allies was a widespread strategy employed by the British from the 17th to 19th centuries, including silver gorgets in the American colonies, medals in the Pacific Islands, and badges of distinction in Australia (Darian-Smith 2015: 54-69). In this case, the “regimental” clothing made for the British military was brought by fur traders to the subarctic in the distant reaches of northwestern North America. While ceremonial clothing was visually striking, it was less important logistically than the fresh meat received in return that helped Porter and his men survive the season.

2 This event, like many others, involved an exchange of various goods that served both material and symbolic functions. Food and clothing are interconnected by their ubiquity in the fur trade and in their close proximity to the body. They can stimulate the whole “sensorium,” defined as the “the entire sensory apparatus as an operational complex”(Ong 1991: 28) by triggering visual, tactile, and olfactory senses, while their production and consumption stimulated the senses of hearing and taste. This article builds on recent studies that examine the material history of the fur trade, focusing on cultural adaptations of clothing and food in historical experiences and expressions of identity. Fur traders and Indigenous peoples traded not only materials, but also styles and even tastes. Euro-Canadian taboos against adopting Indigenous clothing and food were often thwarted by the realities of survival, intercultural exchanges, and trading post life before the mid 19th century. By examining food and clothing together, we can trace how exchanges of materials, styles, and tastes produced hybridized fashions and diet, influencing how identities were expressed and negotiated across northern North America.

In More Than One Sense

3 Historians often trace the transmission of materials over space and time. This article considers the physical and sensory nature of human bodies as the point of departure. Karin Dannehl reminds us of the immense surface area of the human body, which includes inner surfaces of the ear and mouth, nasal passages, and digestive tracts: a “vast tactile area” that shapes our experiences of the external, material world (Dannehl 2009: 130). The connections of clothing and food with identity have the potential to posit layered meanings when considered together as they work their way over the exterior and through the interior of bodies. Multisensory approaches have been advocated because they integrate “the visual into a holistic sensory perception which allows a richer and more ethnographically adequate multivalency of meanings to emerge” (Edwards et al. 2006: 8). By framing the study in more than one sense, we aim to get at what has been described as “the interplay of sensory meaning—the associations between touch and taste, or hearing and smell—and all the ways in which sensory relations express social relations” (Howes 2003: 16-17).

4 Modern sensory studies emerged in the mid 20th century largely out of frustration with European ocular-centrism. Plato and Aristotle both accorded vision as the most important sense, associating it with reason. The European Enlightenment renewed the notion that sight was the “highest” sense and most closely associated with reason, while the so-called “lower” senses of smell, taste, and touch were associated with the body (Classen and Howes 2006: 206). In the early 20th century, many anthropologists identified these senses as playing a more central role in the cultures of non-European peoples. In the 1960s, the discussion was renewed from the perspective of communication studies. The idea that cultures consist of distinct “ratios of sense” was first introduced by Marshall McLuhan and Edmund Carpenter (McLuhan and Carpenter 1960). This school proposed that the “technology” of written language has a transformative effect on consciousness, something which, propelled by the invention of the printing press, effectively secured the ocular-centrism of European culture (Ong 1987: 7-137). While these theorists have been critiqued as overly essentializing and technologically deterministic (Daniell 1986; Faigley 1992), they were attempting to escape an un-reflexive assumption of visual ascendancy across human cultures. This scholarship and the impulse it represents underpins many subsequent sensory-oriented studies. Moving toward a deeper sensory history of the fur trade allows us to get a better idea of what those involved experienced as well as how they perceived themselves and each other.

“The Favourite Fashion”

5 To mention “fashion” and the “fur trade” in the same sentence would have seemed anathema to many 20th-century scholars. The French Annales school helped open the door to the study of fashion as a potent social force. One of its most influential proponents was Fernand Braudel, who declared fashion was an “indication of deeper phenomena—of the energies, possibilities, demands and joie de vivre of a given society, economy and civilization” (Braudel 1985: 323). Yet in his conceptualization, fashion was uniquely European, and manifested only among those in the highest social echelons (Lemire 2010: 11). Other scholars would find this interpretation too limited. Jack Goody wrote “with regard to the claim that fashion was uniquely European, Braudel was quite wrong” (Goody 2007: 265). His own conceptualization was deeply cosmopolitan—it was only in the “major urbanized societies” where fashion could be found. This interpretation makes no accordance for non-urbanized societies or contact zones on the edge of empire. Yet it is precisely here in this less regulated social environment where fashion has the potential to provide insights into cross-cultural encounters.

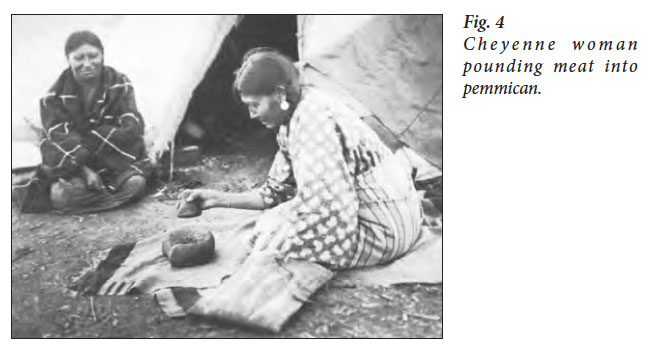

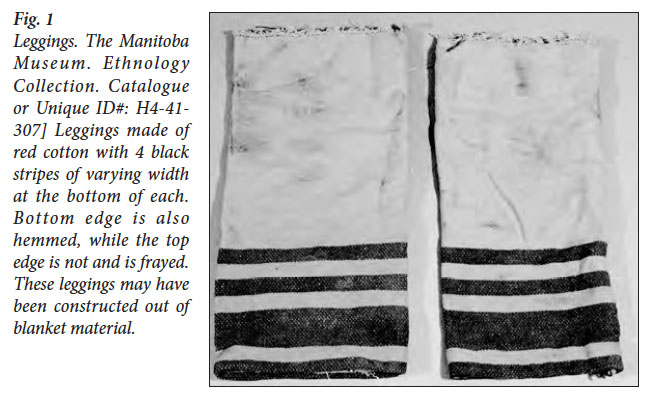

6 Clothing occupies a central position in the articulation of cultural identities. It is imbued with complex economic and cultural significances. Beverly Lemire (2009) has analyzed the “use and evolution of materials” in the international cotton trade. Changes in material culture signal broader historical changes, while garments “defined and expressed priorities,” covering bodies and helping to negotiate their place in society (85-86, 93). The innately sensual nature of clothing provides multi-sensory affects. Rather than possessing absolute meanings or values, garments can be considered, as the authors of Sensible Objects suggest, as “bundles of sensory properties which respond to specific sets of relationships and environments” (Edwards et al. 2006: 8). According to Lemire’s analysis of English textiles in the context of global colonial trade, influences often flowed in both directions from colonizer to colonized. Clothing is “as vital as food and shelter,” yet “the selection of apparel was replete with personal, economic and cultural considerations” (Lemire 1997: 3). In other words, clothing fulfills a number of physical and social functions simultaneously.

7 The social and cultural turn in fur trade historiography was advanced through the study of women and Indigenous history starting in the 1970s. Scholars began to study women’s roles as cultural liasons and material workers, tracing adaptations and the creation of a new society (Van Kirk 1980; Brown 1980). These studies emphasize that fur traders had the peculiar vocational characteristic of working closely with Indigenous peoples in their own communities for long durations, and their experiences and cultural adaptations often contradicted the racial assumptions of settler society that hardened in the later 19th century. The fur trade was not conducted in a “free-market” context, but was subject to the social and cultural dynamics of diplomacy and military alliances. It expanded westward from the fringes of the eastern North American colonies from the 17th to the early 19th centuries, and was predicated on an uneasy balance of power. Richard White traces how material exchanges fulfilled not only economic but symbolic functions. Gift-giving was central to alliance-making ceremonies with Indigenous peoples, and much of what was exchanged consisted of garments of clothing and adornments (White 1991). The “middle ground” was constituted on reciprocity, material exchanges, and ceremonial protocol that demonstrated cultural adoptions and adaptations.

8 In examining the role of clothing on the New York frontier in the mid-18th century, Timothy Shannon explores how both European and Indigenous peoples adopted new clothing in their diplomatic manoeuvrings. The importance of dress extended “far beyond its utility,” argues Shannon, possessing “a variety of expressive properties” that were manipulated. In the context of diplomatic negotiations, powerful symbolic statements were often made through the choice of wardrobe. William Johnson, a British diplomatic figure and later superintendant of Indian Affairs was described as “dressed and painted after the manner of an Indian War Captain” while travelling to Albany in 1746, a time when the British were desperately trying to shore up their military alliances with the Haudenosaunee. That same decade, the Mohawk chief Hendrick travelled to England and appeared in London’s royal court wearing a blue suit, a ruffled shirt with cuffs, a cravat, and a hat trimmed with lace (Shannon 1996: 13-14, 17). These instances involved high-ranking diplomats symbolically adorning themselves in the other’s dress. Yet exchanges and symbolic displays of garments occurred regularly in the small-scale diplomatic proceedings carried on by fur traders at trading posts across northern North America.

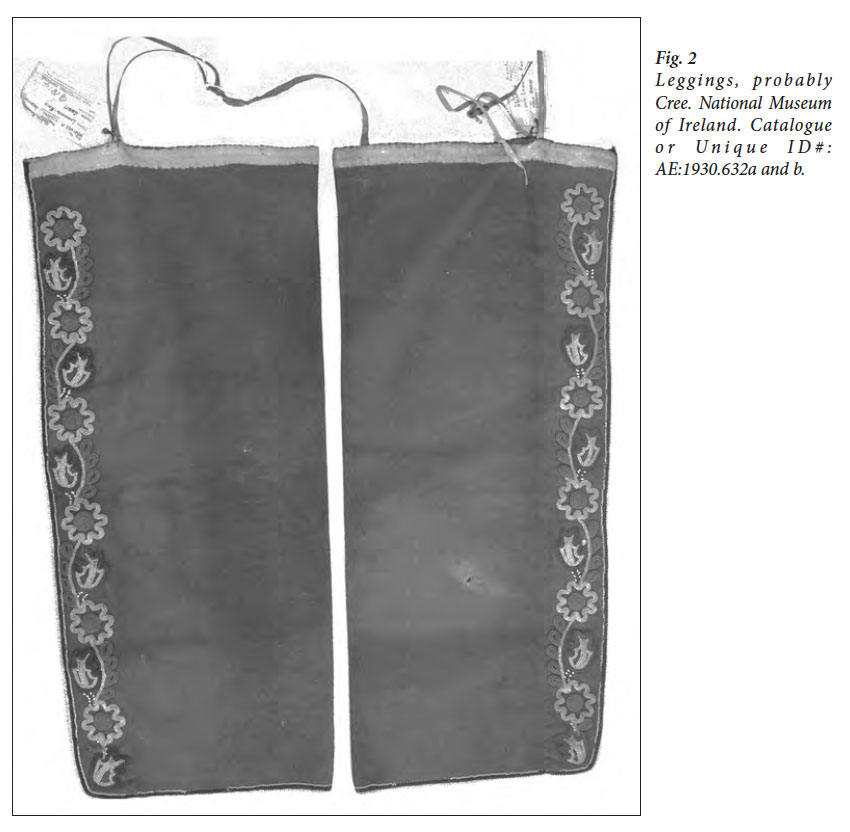

9 Early French descriptions evaluated Indigenous clothing and bodies on standards of appropriateness and decency. In describing various dances of Indigenous peoples, Samuel de Champlain noted that only the Huron men felt “ashamed” by their nudity, not the women. He describes the robes and adornments they wore while dancing (Champlain 1929). At the Great Peace of Montréal in 1701, many Indigenous chiefs were described as wearing “long fur robes.” Yet the appearance of “the more remote tribes” provoked rebuke: their “grave and serious demeanor” seemed to clash with how they “were dressed and adorned,” which the French judged to be in a “manner quite grotesque” (Charlevoix 1870: 148-54). Though what precisely constituted the transgression of style is not specified, perhaps exposed or painted skin violated French notions of decency.

10 Visual markers of status were often quickly learned and transmitted in cross-cultural encounters. Feathers were one potent category of visual symbolism. Samuel de Champlain describes a battle with the Mohawk in 1609 in which he is directed by his Huron and Algonquin allies to target the enemy warriors who had “three large plumes” on their heads, supposedly signifying they were chiefs (Bourne 1911: 207-13). While French explorers and traders adopted moccasins and snowshoes for the purposes of mobility and survival, the French coureurs de bois and voyageurs developed their own distinctive dress that combined European and Indigenous styles, with some adding feathers to their attire (Podruchny 2006). Colin Calloway describes how the “cross-cultural environment of the fur trade” produced hybrid styles of clothing. Indigenous peoples sometimes wore European blankets and coats, fashioning them or adapting them in their own style. Yet “it was equally common to see Scots in Indian country wearing moccasins, leggings, and hunting shirts. Traders who lived and worked in Indian society adopted Indian ways.” Calloway’s account of this transformation deserves closer investigation. While it is true that Europeans and Indigenous peoples “borrowed and adapted each other’s clothing and styles of dress,” the social context through which it was undertaken should be examined in greater detail (Calloway 2008: 135-36).

11 Fur traders sometimes documented dramatic transformations in their physical appearance. The English fur trader Alexander Henry (“the elder”) provides a detailed account of his journey through the Great Lakes in the early 1760s. He describes himself imitating the dress of his French voyageurs by smearing his hands and face with dirt and grease, and covering himself with a cloth “passed about the middle; a shirt, hanging loose; a molton, or blanket coat; and a large, red, milled worsted cap” (Henry 1901: 34-35). Here we have an early description of the toque and the iconic multi-coloured sash, otherwise known as a ceinture flechée, arrow sash, or “Assomption Sash,” which became strongly identified with the voyageurs and Métis (Ens and Sawchuk 2016: 504-506). Henry was one of the first English-speaking traders travelling through the Great Lakes after the fall of New France, and it was dangerous for him to reveal his “true” identity. Yet this habit of the Montréal fur traders dressing like the French Canadian voyageurs would be adopted by subsequent “Nor’westers” operating out of Montréal. A partner of the North West Company wrote from Athabasca in 1795: “we dress in the Canadian fashion” (“An account” 1795: 31-32). This demonstrates the reach of French Canadian culture and the fashion and styles brought and adapted from the St. Lawrence by the voyageurs and fur traders across the long-distance trading networks.

12 The conscious transformation and manipulation of garments indicates their nature as a modifiable interface of identity. Garments can be removed and replaced, and fur traders sometimes changed their clothing and appearance multiple times over during the course of their journeys. Alexander Henry transformed his appearance after narrowly escaping the surprise attack at Michilimackinac during the so-called “Pontiac Rebellion” of 1763. He describes the chief Menehwehna assisting his transformation:

13 Henry identifies the distinguishing feathers, paint, shirt, and red leggings that completed his new appearance. While his hosts, and “the village in general,” appeared to consider his appearance improved, this transformation into Indigenous appearance was one that Henry underwent because he thought his life was at stake (111-12).

14 Red cloth was a highly prized trading item that became associated in the 18th century with Indigenous fashion. It represents the adaptation of European material culture, evolving into a new style of legging that would be transferred back to traders and the colonists of Montréal. It represents the Indigenous adaptation of European material culture, evolving into a style that would be transferred to traders due to pervasiveness and practicality. It represents the Indigenous adaptation of European material culture, evolving into a style that would be transferred to traders due to pervasiveness and practicality. The mitasses, or leggings made of red cloth, were by the mid 18th century identified as Indigenous fashion from Hudson Bay to the Great Lakes. Letitia Hargrave, the Scottish wife of York Factory’s chief factor was “no admirer of indigenous fashion,” yet wore “Indian leggings” when she was living at the trading post (Calloway 2008: 136). In the songs of the voyageurs, this garment was associated specifically with the clothing style of Indigenous women. One declared “dans le Mississippi, ya des sauvaguesses,” wore “souliers brodier” and “mittasses rouge” (Barbeau 1954: 336-50). This denotes a specific cultural association of red leggings with Indigenous women in the minds of the French Canadian voyageurs and their songs, which often boasted lusty lyrics. This style was not only known throughout the Great Lakes but down the Mississippi to Louisiana where mitasses remained a common word among French communities for leggings, as in “une paire de mitasses” (Read 2008: 111).

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

15 Certain colours were considered to hold special qualities, attributes, and meanings. While there were considerable variations in these designations, scholars have attempted to summarize the basic colours used in colonial-era intercultural diplomacy: white generally symbolized peace and good intentions, black symbolized death and ill-will, and red signified fire and emotion (Calloway 2008: 135). These visual associations in turn shaped the perception of garments. Colin Calloway suggests that red garments were a “potent symbol” associated with prayer and sacrifice. The Anishinaabek had long painted red ochre on garments, and red cloth may have been interpreted similarly as a means of expressing relationships with life-giving forces. Yet within the context of the fur trade, the colour red was also associated with British military uniforms, known colloquially as “redcoats” (Brumwell 2002). Evan Haefeli discusses fashion’s relationship with politics, suggesting that scarlet coats were given to influential Indigenous leaders, symbolizing a trading captain or ally (Haefeli 2007: 424-26). Recall James Porter’s journal entry on Slake Lake in 1800-1801. Red jackets were given and traded by English fur traders from the arctic circle to the Carolinas: the Annual Register for 1763 carried a report from Charles Town, South Carolina, that an “Indian trader” had sold the Cherokees “several garments of red baize, much in the nature of the Highlanders uniform, for which he had a valuable return of furs and deer-skins.” These items were traded to the Indigenous individuals most open to pursuing, negotiating, and trading with the British (Calloway 2008: 135). The stylistic influence of the British military is here apparent, transmitted through the conduits of the fur trade.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2

16 On the shores of Hudson Bay, the transmission of red coats with tinsel lace to Inuit “chiefs” was intended to cement trading relations. This garment became considered by the Europeans as a distinguishing feature of high-ranking members of Inuit society. Richard Pococke, Bishop of Meath wrote that the chiefs wear “a red Jacket,” and other forms of wealth such as “purses of Seal Skins adorned with glass beeds, on which they set a great value” (Pococke 1887: 138-39). Unfortunately the extant attributions of value in the written record from this period are those of European observers. These must be examined critically, as the European tendency to interpret class rankings and hierarchy often did not accord well with the structure or perspective of Indigenous societies. Indeed the degree to which prominent members of Indigenous communities conformed to the European depiction of “chiefs” has been debated by historians (White 1991: 16-17). By giving scarlet coats to specific individuals, fur traders signalled allies and cultural liaisons rather than individuals embodying high social status and subsequent power structure akin to European society. And the coat could be passed along, modified, or re-purposed.

17 If the arrival of European garments and trading cloth changed the feeling and appearance of some Indigenous clothing, re-worked metal and bells introduced by the fur trade transformed how they sounded. Clothing was designed to be silent or sonorous, with the former suited for hunting and travel and the latter for displaying, feasting, and dancing. The objects that made garments produce sound before the arrival of European metals were mostly the dewclaws of deer or other hoofed animals. These were attached in pairs or rows to the fringes of dresses, pants, and accessories, striking each other and resonating when agitated (Koch 1990: 43-47). Recent scholarship has explored how European metals were re-worked by Indigenous peoples. Kathleen Erhardt has explored how European copper was encountered as “other worldly” because of previously held cultural associations.2 Cory Wilmot and Lisa Anselmi have investigated how Indigenous techniques were used to re-work European metals into traditional forms such as the cone (Anselmi 2004; Wilmot 2010b). These are found adorning dozens of items in ethnology collections in museums across Canada, hand-made from re-worked metal goods. By the late 19th century, “tinkle cones” became fashioned from cigarette tins, and by the 20th century they had become a mass-produced commodity for Indigenous dancers on the pow-wow circuit.3

18 Bells were adopted on a wide variety of Indigenous garments and accessories. These items reflect the sonic legacy of the fur trade on Indigenous material culture. Large quantities of small bells were introduced, including pellet, hawks, sleigh, table, and horse bells—yet the most prominently traded variety was hawks. In an inventory of York Factory in 1776, hawks bells are the only variety listed (Hansom 1951). On items such as a cradleboard housed at the British museum, hawks bells are the only sound-makers. Other items such as a dance apron include hawks bells alongside tinkle cones. Important religious and ceremonial items such as headdresses were sometimes adorned with hawks bells alongside dew claws. A shoulder bag at the Pitt Rivers museum displays hawks bells alongside other sound makers rather dramatically, including dew claws, brass thimbles, and cones.4

19 The fur trade prominently involved exchanging garments, as furs were traded for blankets and clothing. Yet within this dynamic, there was room for selective adaptations. Fur traders operating out of Montréal often wore the clothing of French Canadian voyageurs, which was inspired in part by Indigenous styles, including fur garments, footwear, and ornaments. Both fur traders and Indigenous peoples adopted articles and selected trading goods according to their own needs and tastes. Red cloth and jackets held widespread cultural currency, promoted by the British and coveted by many Indigenous peoples involved in the trade. Fur traders incorporated aspects of Indigenous dress into their attire. The metal goods of the fur trade were often recycled and repurposed sonorous elements to clothing in a distinctively Indigenous style. Cultural hybridity in fashion became naturalized and identified with the clothing of both Indigenous peoples and fur traders.

Display large image of Figure 3

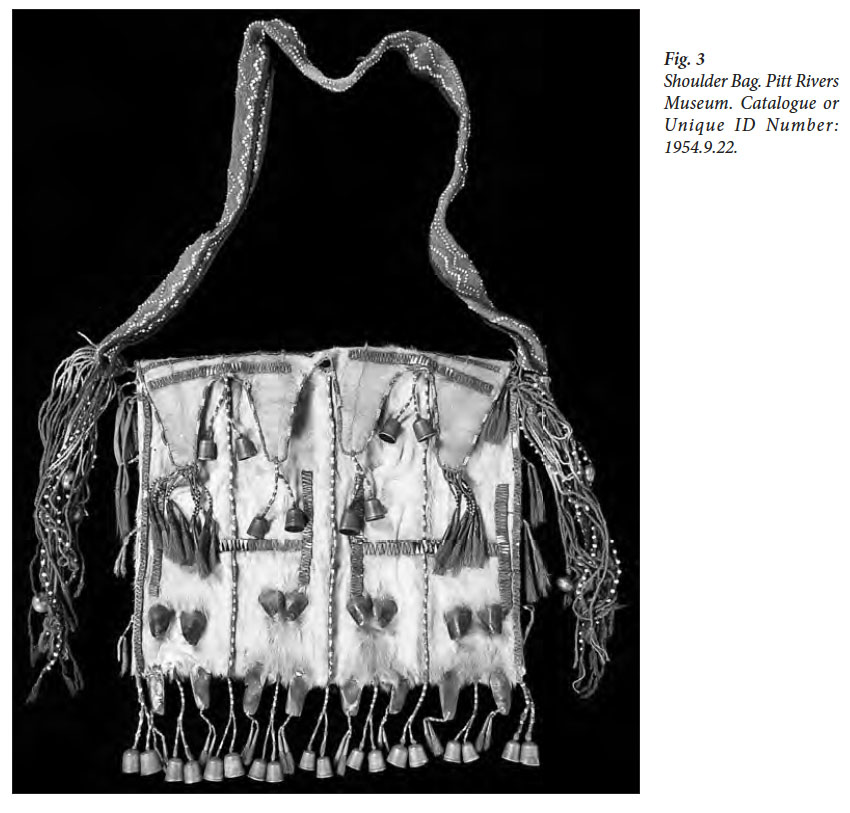

Display large image of Figure 3

Starvation, Pemmican, and Rubbaboos

20 Food has been analyzed by historians as a key of identity that can reveal cultural trends, social patterns, and changes over time. Its materiality is crucial to its status as a commodity, as it can be consumed only once. A vital resource, food is not merely significant as a material object. Particular foods and acts of eating, as well as production, preparation, and distribution, possess important symbolic meanings in human cultures. We can access deeper understandings of the past when evaluating which values, beliefs, and attitudes influenced food preferences (Kirkby et al. 2007). Increasingly, scholars are examining foods as sensuous objects that shaped human experiences. John C. Super asserts that food is an “ideal cultural symbol that allows the historian to uncover hidden levels of meaning in social relationships and arrive at new understandings of the human experience” (Super 2002: 165). With these goals in mind, many scholars have turned to the gastronomic encounters of colonial North America.

21 In Edible Histories, Cultural Politics (Iacovetta et al. 2012), a number of historians examine food’s social and cultural implications in early Canada. Alison Norman examines frontier food identity in 19th-century Upper Canada, tracing the adoption of maize, maple sugar, wild rice, wild teas, fish, and venison by settlers. She argues that both Indigenous and settler communities underwent culinary changes in the contact zone, but that these meant different things to those involved. For settlers, the adoption of Indigenous foods was “part of their transformation from Britons to Canadians.” For Indigenous peoples the “longer trajectory of colonialism” involved state officials and missionaries attempting to impose notions of “civilization,” including changing eating habits (Norman 2012: 41-45). Ultimately, the “contact zones” of Upper Canada led to “new hybrid diets” for British settlers as well as Indigenous peoples.

22 Early settler communities on the other side of the country reveal a similar pattern a century later. Megan Davies describes a “hybrid ‘food-scape’” whereby food security for Indigenous and Euro-Canadians was navigated through “a complex mediation of place, task, season, and civic responsibility.” It served as an important aspect of cross-cultural contact, and provided a “canvas for the (re)creation of Euro-Canadian frontier identities” (Davies 2012: 102). In the post-Second World War conditions that Davies describes, food was “intensely local,” grown, foraged, raised, or hunted in the immediate regions around homesteads. This is a significant departure from the preceding centuries of colonial contact via the fur trade, when Indigenous foodways were crucial for the survival of First Nations and Euro-Canadians alike, and foodstuffs often had to be mobile and procured en route.

23 How did food play a role in transforming Britons and Canadians into fur traders? Elizabeth Vibert has investigated how fur traders navigated in the plateau and basin region in the 19th century, tracing how food was laden with cultural beliefs about identity and physical vigour. Britons often brought their sense of superiority, imposing their own sense of “good taste” and hierarchies of food—for instance privileging meat over fish (Vibert 2010: 123). Vibert argues that understandings of appropriate food and manners were used to secure Euro-Canadian identities and create distance from the Indigenous peoples among whom they travelled and worked. Yet, as she indicates, they were often entirely dependent on Indigenous peoples for their food and security. As the trading post network was expanding westward in the 17th-to-early 19th centuries, fur traders did not have the power or resources to impose their own preferences on their diet. They adapted to available food sources, mostly procured through trade and gathered, harvested, hunted, and prepared by Indigenous people, including cultivated crops, fresh game, and processed foodstuffs.

24 The caloric requirements of fur traders influenced Indigenous economies in the eastern woodlands and the great plains in the 18th century. Native food sources and methods of preparation in turn shaped the fur traders’ diet (Ray 1974). The journals of fur traders indicate an appreciation of Indigenous foodways and agricultural techniques. David Thompson described the harvesting of wild rice when he was exploring westward along the Missouri river in the late 1790s. He notes this grain ripened in the early part of September. His description of its cultivation includes powerful visual and aural sensory stimuli, corresponding to David Sutton’s argument that intersensory connection is a potential facilitator of memory (Sutton 2006: 90). Certainly the detail of Thompson’s description seems to bring this argument to bear, as he describes how a “thin birch rind” was placed on the bottom of the canoe, while a man in the centre

25 This description by Thompson is rich in overlapping sensory detail. It indicates a recognition of the importance of the cultivation of this food produced in the Rainy Lake area bisected by the Montréal fur trade.

26 Alexander Henry’s extensive travels exposed him to the dress and dietary cultures of numerous Indigenous nations. When he made it to the great plains he described material economies that revolved around the bison. Travelling along the North Saskatchewan river, chiefs of various nations would visit with buffalo tongues to eat, sometimes boiled and sometimes roasted (Henry 1901 [1809]: 296-97). He made note of their clothing and use of bison fur, which, when dressed, furnished soft garments for the women, while the men wore dressed furs with the long hairs attached (317-18). In the western Great Lakes, Henry observed different cultures and was often invited to feasts and ceremonies. The Indigenous peoples he encountered here in 1764 “accustom themselves both to eat much, and to fast much, with facility” (142-43). While attending one such feast, he remarks that he “often found difficulty in eating the large quantity of food, which, on such occasions as these, is put upon each man’s dish.” Fur traders who spent long durations in the northwest often became accustomed to both feasting and fasting. Periodic scarcity likely amplified the appreciation of food and joy of eating. David Thompson made an observation in regard to the French Canadians that he encountered along the Missouri river, astonished by their gluttony and habit of eating eight pounds of fresh meat per day (3.6 kg). They told him that “their greatest enjoyment of life was Eating” (Thompson 2009 [1850]: 199). The culture of feasting may have been inculcated by the conditions of uncertainty and scarcity that characterized the periodic and seasonal contours of the trade.

27 Alexander Henry attributed the success of the French Canadian coureurs de bois and voyageurs to their ability to survive on Indigenous foodstuffs. He details the production, preparation, and characteristics of “Indian corn,” connecting it to the social makeup of the fur trade:

28 Here, diet was related to the socioeconomic contours of the Montréal fur trade. While Henry may have exaggerated the extent to which this diet was exclusively adopted by French Canadians, the familiarity of the voyageurs with it certainly facilitated their ongoing centrality as labourers in the trade after the British conquest of the St. Lawrence.

29 Tastes varied as foodstuffs moved across cultural lines. What constituted a delicacy to some could be considered disgusting to others. When fur traders encountered the west coast and plateau regions, for instance, they were greeted with novel flavours, such as those produced by fermenting fish. In the accounts from the Columbian interior at places such as the Kootenays, Spokane, Colville, and Kamloops, there are references to Indigenous people collecting “putrid” or “rotten” salmon, which may have been selected for taste or merely stored for times of emergency in the winter (Vibert 2010: 167-69). Smoked fish and fermented oil were considered delicacies among the Kwakwaka’wakw, yet often offended the taste sensibilities of Europeans (Jonaitis 2006: 141).

30 Taste is often discussed in relation to “class culture.” If, as Pierre Bourdieu contends, having “good taste” in European societies produced “cultural capital” by displaying and reinforcing class distinctions, then alternative foodways might serve a similar function with different standards of evaluation (Bourdieu 1984). The canoes ferrying goods between Montréal and the western end of Lake Superior were provisioned with rations of corn and grease and/or fat. The voyageurs who worked this route earned the nickname “mangeurs du lard” because of this diet, which also connoted rookie statussomewhat akin to “greenhorn.” In contrast, voyageurs operating to the west of Lake Superior were typically reliant on Indigenous peoples for supplies of fresh meat and processed foodstuffs. These men possessed the higher status titles “Athabasca men” or homes du nord (Podruchny 2006: 25-27). Indeed, the lower status of the mangeurs du lard indicates that proximity to the Euro-Canadian food economy granted lower status than those who worked further removed in the fur trade. This indicates a countervailing trend to Eurocentric assumptions regarding food as status symbol and purveyor of cultural capital.

31 Canoe travel is an extremely labour intensive form of transportation, with many mouths to feed over the long voyages. While fur traders brought alcohol and tobacco into Indigenous communities, they did not typically bring sufficient foodstuffs for their own survival. The Anishinaabek came to call English rum “milk,” a gift-giving metaphor and symbol of reciprocity that Bruce White has demonstrated held deep significance around Lake Superior (Henry 1901 [1809]: 242; White 1981). Alcohol was incorporated into trading rituals, yet over-reliance by many traders undoubtedly contributed to instances of violence and patterns of substance abuse (Podruchny 2006: 181-84). Alcohol did not prevent starvation: indeed it may have occasionally perpetuated it. It was a commodity that was traded for food and furs and then consumed. As a material object and symbol of reciprocity, it was used by fur traders to survive in Indigenous communities by trading it for food. While fur traders were frequently vulnerable to starvation, they nonetheless often described Indigenous people as being in such a state, often mischaracterizing their dietary culture in the process. For instance, in the Columbia and plateau regions in the early-to-mid 19th century, fur traders sometimes depicted Indigenous people as being in a condition of starvation without understanding seasonal contours or subsistence patterns (Vibert 1997: 164-65).

32 How fur traders coped with periods of scarcity varied. The logistics of the industry, with its isolated trading posts, the long winter months of the northern climate, and the many mouths to feed, meant that starvation was an ever-present danger. This was particularly the case when summer turned to autumn, and the long-distance canoe and York-boat networks came to a stand-still. With their position in or near Indigenous communities, the extension of credit, and the culture of small groups of traders being sent to overwinter with Indigenous communities, relationships of reciprocity inevitably developed. Rum, tobacco, and goods were used to encourage Indigenous hunters to bring returns of fur and food: “as they interacted, lived in commune and passed wild meat between them, social obligations inevitably accrued” (Colpitts 2007: 74). There was an environmental factor as well, as the prairie ecology was subject to dramatic seasonal contours that “favoured food reciprocity” (58-59). Food sharing networks were secured and extended through kin-obligations produced by intermarriages as well as personal relationships forged with local hunters. Eager to maximize returns at the posts, fur traders sometimes wrote about poor returns and extending provisions and credit very begrudgingly. The factor of Pine River fort in 1807 wrote of “abusing” Indigenous hunters whom he felt had made a “scandalous hunt” (“Northwest Company Papers” n.d.: 104). Yet others extended credit and accepted this reality of the industry. North West Company clerk George Nelson wrote in 1815 at Manitonaningon Lake: “I know I will be blamed for this, but I do not care so long as I can do otherwise I shall never allow a man to starve at my doors” (Nelson 1815: 4). The principles of reciprocity and sharing in this case trumped the immediate quest for profits.

33 Due to the centrality of one particular food source, the immense networks of the North West and Hudson’s Bay Companies around the turn of the 19th century has recently been dubbed a “pemmican empire.” The word “pemmican” comes from the Cree word meaning “he makes grease” (Colpitts 2014: 8-9). Its most essential feature is hard and soft fats extracted from the marrow of bisons’—and/or other animals—long bones, along with others that are boiled and crushed. Its preparation was labour intensive and difficult to execute properly. Harold Innis recognized the geopolitical significance of this particular processed food in the operation of the fur trade. Just as corn and grease were essential to the trade between Montréal and Lake Superior, so too was pemmican essential for its expansion into the Athabasca and the northwest. Innis acknowledged that these foodstuffs were essential and that “in the production of pemmican the Plains Indians occupied a strategic position,” an admission of Indigenous agency and importance absent in other histories of the time (Innis 1973 [1956]: 235). Arthur Ray advanced the study of the role of Indigenous hunters, identifying the importance of “country produce,” which he defines as “food and a variety of other products,” the procurement of which together became “a core economic activity for many aboriginal economies after the initial fur-trade phase” (Ray 1974: xvxvi). He traces the bison hunt and the interplay with subsistence methods in the borderlands between the plains and woodlands, providing its environmental and seasonal contours, which persisted long before the arrival of Europeans trading for furs (Ray 1974: 27-35).

34 Yet the demand for pemmican dramatically increased in the late 1790s with the expansion of the fur trade. Peter Fidler expressed disbelief in the amount of food his men ate, estimating the people in and around his trading post consumed 30,000 lbs of dried meat in one summer (13,600 kg). He became notorious for insisting his men eat fish in the summer so that as much meat as possible was set aside (Ray 1974: 129-30). In 1807 near Cumberland House he describes his men making 100 pounds (45 kg) of “Pimmican” (Fidler 1806-1807: 24). He worked aggressively to purchase as much meat as he could from the bison pounds when he was placed in charge of coordinating the Red River settlement’s supply of food at Brandon House. Pemmican was crucial to the fate of the commercial struggle between the North West Company’s trading network and the Hudson’s Bay Company’s Selkirk settlement. Access to this resource would prove so contentious that the HBC Governor Miles Macdonell’s “Pemmican Proclamation” of 1814 would disrupt production by the Métis for the North West Company (Colpitts 2014: 100-47). Pemmican was confiscated and the networks that supplied the Montréal trade threatened. The ensuing agitation erupted into violence at the Battle of Seven Oaks in June of 1816. This bloodshed would in turn contribute to the amalgamation of the North West and Hudson’s Bay Companies.

35 Indigenous communities provided Europeans with foodstuffs, both fresh meat and processed foodstuffs like pemmican, so that they might conduct their trade. The array of responses to novel olfactory and taste experiences was diverse. One of the early settlers of Red River described how Indigenous women made pemmican by pounding the buffalo meat, pouring melted fat on top, and sewing it up in a buffalo hide. In her opinion, “Pemmican made carefully from the best parts of the buffalo, with the right mixture of sugar and berries to correct the greasiness, was very good” (Healy 1967 [1923]: 155-56). An observer in the 1850s similarly described how “Saskootoom” berries act as a “currant jelly does with venison, correcting the greasiness of the fat by a slightly acid sweetness. Sometimes wild cherries are used.” He paints an unsavoury portrait of some pemmican made from hard meat, “tallowy rancid fat,” “long human hairs,” and “short hairs of oxen, or dogs, or both.” Yet he concedes that “carefully-made pemmican, such as that flavoured with the Saskootoom berries, or some that we got from the mission at St. Ann, or the sheep-pemmican given us by the Rocky Mountain hunters, is nearly good—but, in two senses, a little of it goes a long way” (Southesk 1969 [1875]: 301-302). Appraisals of pemmican’s taste often included discussions of its utility, as even those who disliked its taste recognized its usefulness as an energy source.

36 Pemmican was further processed by fur traders and voyageurs on their journeys. The most popular treatment was called “Rubaboo” or “Rubbaboo,” and involved boiling and or frying the pemmican with grease and/or flour. Alexander Mackenzie describes how he and his voyageurs would prepare pemmican in a few different ways, whenever possible avoiding eating it cold. He and his men thought it superior to other processed foods such as dried fish (Mackenzie 1931: 111-17). He describes strategies for making it more appetizing, including adding wild pars-nips, or wild onions, and heating them together in the kettle (107, 159). The Earl of Southesk described how his men would “fry it with grease, sometimes stirring-in flour, and making a flabby mess, called ‘rubaboo,’ which I found almost uneatable” (Southesk 1969 [1875]: 301-302). Yet this seems to have clearly been the method of preparation preferred by fur traders. Robert Kennicott described cooking pemmican with a little flour and sugar along with melted snow. The fusion of European and Indigenous foodways became a metaphor signifying other hybridized aspects of culture produced by the fur trade: Kennicott describes how it came to describe “any queer mixture” of things, including patterns of language and even music. When he tried “to speak French and mix English, Slavy, Loucheux [Gwich’in] words with it, they tell me, ‘that’s a rubbaboo.’ And when the Indians attempt to sing a voyaging song, the different keys and tunes make a ‘rubbaboo’.”5 This descriptive language during the 19th century indicates something of the pervasiveness of food and culinary metaphors in discussing fur trade culture.

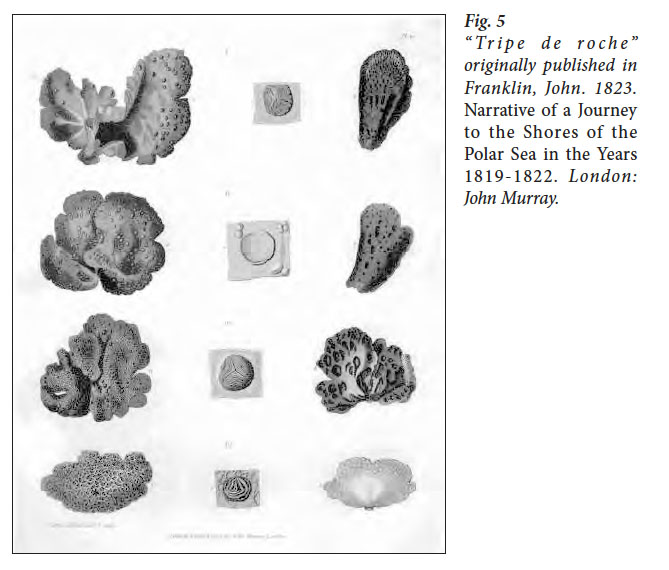

37 When pemmican ran out and all other food sources were absent, crews aboard the long-distance brigades had one final resource. It was a fungus that grew on the side of rocks found throughout the Precambrian shield of northern North America. Alexander Henry describes this fungus that “the Chipeways call waac, and the Canadians, tripe de roche.” He was told that “on occasions of famine, this vegetable has often been resorted to for food” (Henry [1901] 1809: 214-15). Fur trader Daniel Harmon describes it as a crucial food source, but especially important to the Nipigon First Nations who were “frequently obliged, by necessity, to subsist on [it].” It was “a kind of moss, which they find adhering to the rocks, and which they denominate As-se-ne Wa-quon-uck, that is, eggs of the rock” (Harmon 1904: 280-81). Not only did Harmon provide an Indigenous identification of this food, but he speaks from sensory experience when he writes that “this moss when boiled with pimican, &c. dissolves into a glutinous substance, and is very palatable; but when cooked in water only, it is far otherwise, as it then has an unpleasant, bitter taste.” By adding the tripe de roche to pemmican, it could feed more hungry mouths. Harmon confirmed the utility of tripe de roche as a last resort: “there is some nourishment in it; and it has saved the life of many of the Indians, as well as some of our voyagers” (280-81). One starving fur trader shaved the fur off his pelts and boiled the skins in a broth made with the bitter lichen. It effectively saved his life, although it also apparently led to severe intestinal cramping (Colpitts 2007: 72). To survive periodic and seasonal scarcities, fur traders were forced to adapt their diet to the food available.

Conclusion

38 Clothing and food are categories of material culture that held special significance in the fur trade. They are linked in their inherent sensuality, in their proximity to the exteriors and interiors of human bodies, as well as their centrality to the operation of the fur trade. Their close association with cultural identity make them ideal for tracing the contours of fluid and hybridized identities that manifested. By examining clothing and food together, we can see how the most critical material exchanges were often patterned on reciprocity. Whether through gift-giving or trade, alcohol, tobacco, gifts, and woollen garments were often exchanged for furs and food. The North American fur trade was predicated on Indigenous hunting and labouring economies. Clothing for warmth and food for energy were matters of life and death to both European fur traders and Indigenous peoples, but it required fur traders to most significantly change their habits in the new environments. Material exchanges produced adaptations in styles and tastes, as objects were modified and styles of adornment and consumption developed anew.

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5

39 Fur traders embodied innovations that combined old and new materials. Clothing styles evidence a consideration of sensory affect, whether visual or sonorous. Some garments such as the red leggings that were adopted by Indigenous peoples and traders evidenced intercultural transmissions and the creation of new hybrid styles. Very popular at the time, its legacy has not persisted as strongly as the other symbols of fur trade and Métis identity such as the Assomption Sash. The diverse foods, crop management, and processing encountered and described by fur traders belies stereotypes about Indigenous helplessness and dependency. Indeed, fur traders were most dependent, supported by relationships of reciprocity, and often relying on Indigenous procured and processed foods to survive. Those they relied on most, such as corn and pemmican were adapted in ways that made them more palatable to tastebuds and sometimes more nutritious. The best example of this is the rubbaboo, which symbolizes the pattern of culinary exchanges produced by the fur trade. Food and clothing were primary categories of material culture and contact for colonial bodies, producing sensory experiences and shaping cultural and material encounters. The fur traders’ vocation required close contact with Indigenous peoples and material culture over prolonged intervals, producing exchanges and interactions that encouraged the adoption and adaptation of materials and introduced various styles and tastes. Here manifested the hybridity of cultures and identities that has been recognized as one of the most distinctive outcomes of the North American fur trade.

This paper was first presented at the Canadian Historical Association’s conference at the University of Ottawa in 2015. I would like to thank the participants and especially Mary-Ellen Kelm and Stacy Nation-Knapper for their comments.