Articles

Going Strong:

The Role of Physical Strength among the Scots of Eastern Nova Scotia and Cape Breton

Abstract

Drawing on the disciplines of social history and folklore, this article examines a much-neglected dimension of local story lore—feats of strength stories—among the immigrant Scots and their descendants in Eastern Nova Scotia and Cape Breton. Fieldwork conducted in both Gaelic and English, as well as print sources, document the rich prevalence of stories about exceptional physical strength and stamina, which once served as vital expressions of identity and community. These stories still form a vigorous component of the regional folktale corpus and represent a favourite genre among tradition bearers.

Résumé

Cet article, qui s’inspire de données propres au folklore et à l’histoire sociale, examine une dimension trop longtemps négligée des traditions locales—les exploits de personnes fortes—parmi les immigrants écossais, ainsi que leurs descendants dans l’est de la Nouvelle-Écosse et au Cap Breton. Des interviews menées tant en gaélique qu’en anglais, de même que des recherches dans des sources imprimées, révèlent une abondante collection d’histoires au sujet d’individus possédant une force physique exceptionelle; de plus, ces récits servirent à cette époque à exprimer leur identité et leur sens communautaire. Ces histoires font toujours partie du recueil de contes populaires dans la région et représentent un genre très apprécié de ceux et celles qui transmettent cette tradition orale.

1 There is a folk tale once told about the Robinsons of Blues Mills, Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, of how young Jean Robinson struck a bargain with the fairies (Blue 1976: ifc, 40). She could have had anything for the asking—immortality, fame or fortune. Instead, she spurned these choices, stating as her preference that her children and descendants would be blessed with remarkable “physical strength.” This story, however entertaining, contains a profound insight—that among the Scots and their descendants, physical strength was an all-important attribute.

2 For centuries, the Gaelic imagination was populated with superhuman heroes, beings of often preternatural dimensions and phenomenal strength, who were mighty enough to create mountains and rivers. Even mortal protagonists who were credited with exceptional brawn enjoyed honoured status among Gaelic-speaking tradition bearers as part of their storytelling canon about superior physical power and endurance. As the diasporic Scots fanned out to new homes around the globe, this story genre was a fellow traveller and served as an important vehicle for expressing identity and community.

3 In 19th-century Eastern Nova Scotia and Cape Breton, the Gaelic hero stories and wonder tales of the past were supplemented by localized versions of stories about feats of strength. Fashioned from the rugged exploits of settlers, who earned their own laurels of honorific glory, this local story lore provided endless grist for Gaelic- and English-speaking storytellers. However, these examples of muscle and sinew, anchored in the realm of the everyman and everywoman, should not be conflated with the extraordinary physical accomplishments of Angus MacAskill (1825-1863) of St. Ann’s, Cape Breton, who became a national folk legend renowned for his massive size and strength. By the 20th century, most of the Giant MacAskill stories flowed from the pens and imaginations of writers and tourism promoters, who regaled readers with well-travelled tales about the Giant’s thunderous snoring, which could be heard “the distance of two miles” (3.2 km); of the human leviathan who effortlessly set a 40-foot (12 m) mast onto a schooner; who hefted a ½-ton boat onto its beam ends to drain the bilge water; and who raised the plough from his field, as if lifting a broom, to point out the direction for a neighbour (Stanley-Blackwell 2015: 28). In this article, MacAskill will take a back seat to lesser-known local examples of physical strength, who, although they never achieved the Giant’s iconic status, were more representative of folk tradition. Nova Scotia’s Scottish immigrants and their descendants did not regard physical strength as the exclusive property of a single individual. In fact, in their own oral repertoire, they rejected the triumphal tone and the celebration of the ethic of individual performance which the Giant’s tales promoted, seemingly pushing all other contenders aside. Although the vernacular version of strength stories has been hitherto neglected by scholars, Neil MacNeil, author of The Highland Heart in Nova Scotia, wrote in 1948 with the authority conferred by first-hand experience: “When the Cape Bretoner speaks of heroes he speaks of strong men. When he refers to his ancestors he does not brag about their kindliness, their intelligence, their bravery, although he might well do so, but about their physical strength” (MacNeil 1998 [1948]: 185).

4 Today, these stories still represent a vital and vigorous component of the regional folktale corpus in both English and Gaelic—a favourite genre for tradition bearers of various ages. Fieldwork in Cape Breton and Eastern Nova Scotia has yielded a vast reservoir of oral information, abounding with details about ordinary farmers who once mowed fields with hand scythes as effortlessly as “walking down the road,” blacksmiths who used their hands like wrenches, female forebears who hefted bags of flour as easily as sugarloafs, powerful men who carried barrels of salt ashore with as little effort as bags of wool, or railway men who handled ties like matchsticks (interviews John MacLean, June 28, 2010; A.J. MacMillan 1986: 206; John Hughie MacNeil, August 6, 2010).1 Despite the fact that Angus MacAskill’s posthumous reputation assumed larger-than-life dimensions, his mythology, in all its permutations, did not completely silence folk memories of other local feats of strength, which have been retold generation after generation, surviving Gaelic language shift and crossing over effortlessly into English. As one tradition-bearer stated, “Well I think, no matter where they were, the topic always came up, who was the strongest” (interview Maxie MacNeil, September 8, 2005). Although such stories shade together and can be broadly classified as feats of strength narratives, they possess recognizable and nuanced story elements that cohere around such distinctive motifs as wild animals, workplace sites, games, sports, courtship, community identity, ethnic pride, and family honour. In this way, bearing the stamp of collective authorship, these narratives epitomize the ways of life, values, and customs of the Scots who settled in Eastern Nova Scotia and Cape Breton.

5 During the 19th and early 20th centuries, many feats of strength stories found their way into published local histories, which gave an alternative narrative form to this category of oral literature.2 They frequently showcased individualized community heroes, who outshone their contemporaries in terms of strength and stamina. Singled out for special mention were the likes of Big Lauchy McIsaac, who trudged through spring slush from Dunmaglass to his shanty on the top of Eigg Mountain, with a barrel of mackerel in a sack on his back, or John Dewar of Pictou County, who was “constitutionally as strong as a lion and could endure hardship sufficient to kill a dozen men” (MacLean 1976, vol. 1: 113; Eastern Chronicle February 25, 1886). These same histories are also replete with stories about the local men and women who performed daily pioneer tasks of noteworthy endurance, such as hauling sacks of meal or salt over vast distances. According to M. D. Morrison, author of the April 1904 Blue Banner article, “The Early Scotch Settlers of Cape Breton,”

6 In such a setting, stories about physical prowess offer more than just a flourish of local colour. Set in historical time, they furnish minute details, identifying locales and individuals by name and specifying the actual distances and weight of the objects borne. For example, John R. MacInnis (1890-1972), a local Antigonish County storyteller, stated that Little Allan MacDonald carried 100 pounds (45 kg) of corn meal and a pound (.4 kg) of tobacco from Antigonish to his home in the Keppoch, a distance of more than sixteen miles (25 km) (MacDonald-Hubley 2008: 131). Similar particularity can be seen in the description of John MacKay from Diamond, Pictou County, who heaved a table forty inches square (1 square metre) of curly birch and bird’s eye maple, along a blazed forest trail from Diamond to Lime Rock, fording en route the West River (“A few interesting”: 1).

7 Oral accounts of feats of strength, still recounted with an easy familiarity by tradition bearers in Eastern Nova Scotia and Cape Breton, share a ubiquity and persuasive realism with their published counterparts. For example, during an interview in 2005, Father Allan MacMillan of Judique, Cape Breton, vividly recited the story of Seumas Allain MacMillan, who carried “without saying a word,” to the top of the mountain near Rear Beaver Cove, the contents of a flour barrel in a knotted makeshift sack fashioned from the sail of his boat (interview MacMillan, August 14, 2005). Tradition bearer Murdock MacNeil recounted a story in which a woman transported on her back a butchered pig, upwards of 200 hundred pounds (90 kg), from Benacadie Glen to Piper’s Cove, whereas Willie Chisholm of Heatherton told of his grandmother who once carried a two-hundred pound (90 kg) barrel of flour (interviews MacNeil, June 28, 2005; Willie Chisholm, August 24, 2005).

8 The long distances walked by Scottish pioneers were significant markers of their physical strength and endurance. In his history of Antigonish County, Father MacGillivray stated that the Keppoch residents sometimes attended Sunday mass in Antigonish, a distance ranging from twelve to sixteen miles (19-26 km), while the women residents at the Ohio were known to travel as far as Arisaig to attend church, a trip of no less than twenty-five miles (40 km) (MacLean 1976, vol.1: 83; 1976, vol.2: 82). MacKenzie’s (1926) History of Christmas Island recounts how James Cameron and Sarah Campbell of Big Cove, Richmond County, braved raging winter storm drifts to find a priest to perform their marriage ceremony. The complete trip took them from Castle Bay to Sydney, then to Low Point and back to Castle Bay, travelling on foot approximately one hundred miles (160 km) to secure the church’s blessing of their union and returning to Castle Bay with sufficient energy to dance the wedding reel. Stories about testing human limits by trekking miles for religious purposes served as exempla of courage, stoicism, and devotion. Often strength of character and arm were so seamlessly entwined as to be virtually synonymous.

9 Women did not go unheralded for their ruggedness in narratives about early settlement. So, it is recorded that Mary MacKillop walked barefoot from Arichat to L’Ardoise with half a barrel of flour on her back (Cumming et al. 1984: 33). According to Archibald MacKenzie, Catherine McInnis of Grand Narrows showed no signs of frailness when she cheered on her son at a kitchen party brawl. In fact, she helped roll up his sleeves, unbuttoned his collar to ready him for the fray, and then pitched in, with a blow that floored one of his opponents. Likewise, “Big Mary” McInnis, Catherine’s daughter, was no weak reed (Davey and MacKinnon 1996). While visiting Red Islands, she humbled some “big able men” who were exhibiting their strength by lifting a boulder (MacKenzie 1926: 46). As an object lesson of the physical superiority of the Grand Narrows’ womenfolk, she promptly hiked her skirts, piled another rock on top and hoisted them both. In the 1850s, Ann Cameron Mackay, a midwife in Guysboro Intervale, used her formidable strength to save the lives of several workmen, who, along with her brother, were constructing a carding mill. Using a peavey, she prevented one of the walls, on the verge of collapse, from crushing several men under its weight. This exploit, it is said, capped her local reputation as a “big, strong woman” (Halsall 2005: 16). The spinning wheel arguably constitutes one of the most popular motifs in female strength stories. It is frequently represented as the faithful travelling companion of women who participated in all-day spinning frolics. Take, for example, Ohio’s (Nova Scotia) “Big” Flora Cameron, born in Scotland in 1826, who regularly walked between Antigonish County’s Ohio and College Grant, carrying her spinning wheel on her back for the round trip (interview Brown, April 26, 2010).

10 Stories of physical prowess were also a staple component of family histories among Eastern Nova Scotian and Cape Breton Scots. The McDonalds of Dunmaglass, Antigonish County, for example, boasted an enviable ancestry of strong men, namely, Rev. Alexander McDonald, a “brave man,” who did not hesitate to “use the arm of the flesh in order to secure his rights,” his son, Angus, who customarily sent his adversaries “home in a blanket,” and his great grandson, Allan, who was “reputed to be the strongest man of his time in the Western Highlands.” (MacLean 1976, vol. 1: 54). For Mary A. MacDonald, family pride was buttressed by accounts of the superhuman stamina of her grandfather, Allan MacDonald, who came to Arisaig from Lochaber, Inverness-shire in 1816. Tossed overboard in a “violent snow-storm,” he braved the stormy waters, swimming ashore with his outer garments clenched between his teeth (Rankin 2005: 18). For Antigonish County’s Angus Ban MacGillivray and William MacGillivray, the reputation of their brother John, a soldier in the British army, conferred significant prestige on their family. During the Battle of the Nile in August 1798, he had allegedly killed, in one day alone, “twenty-one men with his own hand.” Although John eventually headed to Central Canada, his attendance at a Sunday mass in Arisaig drew a large crowd; such was the curiosity to “see this powerful man” (MacLean 1976, vol. 1: 127). For generations of Antigonish County Chisholms, ancestral pride was enhanced by the achievements of Kenneth Chisholm who allegedly heaved 400-pound (181 kg) stones to the top of the towers of St. Ninian’s Cathedral, Antigonish’s Romanesque showpiece, which was completed in 1874 (interview Willie Chisholm, August 24, 2005).

11 The theme of physical strength was also integral to the foundational mythology of at least one Scottish immigrant community in Nova Scotia, namely Guysborough County’s Giant’s Lake. Established in the early 1840s, this settlement reputedly took its name from the size and feats of strength of Donald McDonald, “a powerful and courageous man,” who was one of the original Scottish settlers. Local storytellers attributed his fame to an encounter with a serpent-like monster, inhabiting a swamp near his home, which he decapitated with a scythe and a rake (The Casket April 21, 1932). According to an earlier Antigonish Casket article (MacFarlane 1896), local lore deemed physical strength a decisive factor in cementing Angus Cameron’s property claim at Margaree Forks, when he challenged a Mi’kmaw man to a wrestling match to settle a dispute over land use. One version stated that Cameron’s “iron grip” proved invincible for his “antagonist,” who retreated after “a fight that lasted for several minutes.” This story contained both general and specific meanings, for it seemingly validated Cameron’s “full and undisputed possession of his farm,” as well as the pre-emptive might of settler colonialism (MacFarlane 1896; Creighton and MacLeod 1979: 175; Newton 2011: 83-88).

12 In their cultural constructions of strength, Scottish immigrants generally looked for correspondences in the animal world rather than in classical or biblical human archetypes such as Hercules, Goliath or Samson. In Antigonish County, for example, could be found such nicknames as “Andrew the Bear,” “John the Ox,” and Duncan the Whale.” Interwoven into Eastern Nova Scotia and Cape Breton’s feats of strength stories were also elements of a homespun bestiary, where human beings were pitted against wild animals, usually a bear, in life-and-death struggles. Merchant and farmer, John Cameron of Little Judique, described as “a good representative of his clan in size, courage and strength,” confronted a large bear that had been preying on his sheep (MacKenzie 1926: 13). Without firearms, he cornered him in the sheep pen. After a brief skirmish the bear’s back was broken on a log and Cameron emerged unscathed, his exploit earning the plaudits of a local versifier.

13 In the early 19th century, Pictou County’s Alexander Falconer was no slouch when it came to testing his strength against the brute force of wild animals. Especially legendary was his encounter with an enraged full-grown bear bestirred from a winter den. “[W]ithout a moment’s hesitation” Alexander caught him by the ears and “pinned his snout to the ground,” retaining a firm grip until his companion, Farquhar Falconer, had speared him with his pitchfork (Grant 1947: 56). The stories of Alexander McKay, a St. Mary’s resident, who was characterized as “somewhat colossal in his build,” flowered into legend over time. It is said that “In McKay’s hands, all kinds of horned cattle,” even “the fiercest of bulls,” were “as helpless as so many pups” (Grant 1947: 28). On one occasion, McKay found himself paired with a charging bull, which he seized and butchered “on the spot” (27). Women shared near equal billing with men in this variant of feats-of-strength stories. According to Father D. J. Rankin, a Mabou mid-wife, nicknamed “A Chailach Bhan” (“The White Woman”), who came from Scotland around 1809, was renowned for her altercation, while only eighteen years old, with a “huge” black bear which she beat so forcefully with a stick that she crushed its skull. Rankin marvelled: “What was her father’s surprise when he finds on his return that his daughter had performed a feat that would tax the strength and courage of the strongest man in the country” (D. J. Rankin papers: 4). According to historian Carolyn Podruchny, bears, as one of “nature’s fiercest beasts,” epitomized for European settlers “a frightening and perilous wilderness” (2004: 13, 11). Voyageur bear tales, she notes, seldom featured guns, thereby enhancing the mystique of an act of self-defence that “required greater strength and courage” (13). For the immigrant Scots, the typical bear-fighting arsenal included little more than a stick, a firebrand, and occasionally an axe.

14 In this tradition, human beings retained their primacy in interactions with animals on the farm, as well as in the woods. There are numerous examples where the muscular powers of human beings eclipsed those of their farm animals. “Big” Donald McGillivray of Dunmore, Antigonish County, proclaimed the “strongest man who ever came from the Highlands,” put his team of sluggish oxen to shame by unhitching them and taking the chain around his shoulders in order to haul the load of logs up a hill (MacLean vol. 2: 93). Deacon McKay of Pictou County, a man of “towering stature,” regarded himself as a superior substitute for horsepower. On one occasion, he replaced a horse which balked at hauling logs to a hilltop; hitching himself to the double whipple tree, he finished the task in tandem with the remaining horse (Grant 1947: 32). According to Heatheron’s Willie Chisholm, his grandfather and a neighbor, Kenneth MacKenzie, lacking horses or oxen, once took up the chains attached to a plough in order to finish Kenneth Chisholm’s field (interview Chisholm, August 24, 2005). In more recent times, Red Angus Rankin proved fleeter than a horse and sleigh on the harbor ice at Mabou, even though he was wearing an old pair of skates (interview Rankin, July 7, 2010).

15 Stories of strength were also frequently linked to 19th- and early 20th-century work sites. For Alex McKay of St. Mary’s, Pictou County, an East River barn raising was the setting of one of his epic feats. He rescued a drowning man from a spring freshet by leaping into the river from the timber framing of the barn, a distance calculated to be no fewer than fifteen or sixteen feet (4.5-5 m) (Grant 1947: 29). For Hector Neil Hector MacKinnon, a storm-tossed ship captained by Captain Livingston during the August Gale of 1873 proved a testing ground for physical endurance and immortality. He saved the ship and the lives of all on board, by climbing out onto the bowsprit to pull in the sails, maintaining his grip despite the onslaught of heavy waves, high winds and being submerged in the cold Atlantic several times (interview Murdoch MacNeil, June 28, 2005). Hardiness was apparently one of the chief requisites for being a mailman in early Cape Breton, at a time when rough-hewn paths barely sufficed as roads. Three brothers, Malcolm, Hector and Angus McNeil, had few equals on the mail run between Sydney and Port Hawkesbury. With mail bags strapped to their packs, they mastered this distance on foot or by snowshoe, sometimes skating, when ice conditions permitted, from East Bay to West Bay, a distance of more than fifty miles (80 km) (Currie 1933: 12).

16 The field at threshing time could also serve as a theatre for displays of physical superiority. Duncan Stuart Cameron, who was born in Eastern Pictou, ca. 1853, recalled that both men and women became “expert in the use of the sickle” and “engaged in contests over the largest number of sheaves cut in the day” (Cameron ca. 1943: 31).

17 Among Eastern Nova Scotia’s Scots, certain objects, such as ploughs and anvils, were standard fixtures for displays of physical strength. Horseshoes were also a popular accoutrement for strong men and even strong women. Six-foot five-inch Big Ranald MacLellan, a Broad Cove blacksmith, could bend a horseshoe into the shape of a figure eight; one of his creations hung in the River Denys Railway station for many years (MacGillivray 1977: 62). A MacRae woman of Sutherland’s River, Pictou County, had a similar knack, and is remembered for her ability to straighten out a number 5 horseshoe (MacKenzie 2003: 134-35). Stones were also central stage props for feat-of-strength performances. As the stones endured, so too did the tales of those who pitted their strength against them.3 The lifting stone in Gairloch, Pictou County, enjoyed notoriety which dated back to the 1820s, possibly earlier. Situated near the main post road between Truro and Antigonish, about half a mile from Gairloch Lake, the stone drew aspirants from as far away as Musquodoboit to compete for the coveted honour of mastering the historic stone. In the late 19th century, only three men in Gairloch earned this distinction: “Big Murdoch MacKenzie could let air under it. William Ross (schoolmaster) could lift it one inch off the ground, and “little” Alex Sutherland could lift it up to his knees” (Hawkins 1977: 43). In 1923, Gairloch’s lifting stone was transported to Pictou to be displayed prominently on the exhibition grounds at the Hector Celebration. Much more than a novelty for curious tourists, the stone stirred the ethnic memory of locals, who strived to “prove to their fellows that we still breed strong men who quail not over muscular feats accomplished by our grandfathers” (Eastern Chronicle, September 18, 1923). At the crossroads in Benacadie, the site of a large boulder became a favourite Sunday afternoon haunt for local men. Tradition bearer Michael Jack MacNeil narrated the interactions between the boulder and the would-be strong men, illuminating its cultural context as follows:

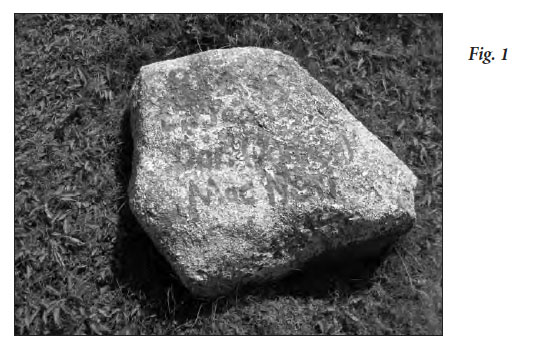

18 In Big Beach, Cape Breton, a boulder, like its counterparts in Gairloch and Benacadie, lured many muscular contenders from Christmas Island Parish.5 This landmark survives to this day, an object of continued pride for the property owner who keeps it freshly painted, including the name of one of the strong man who hoisted it (see Fig. 1). At the turn of the 20th century, Duncan Sorley MacDonald of Queensville, Cape Breton, was forced to improvise with a whetstone when tempers flared at a local wedding. To punctuate his angry outburst, he grabbed the implement and threw it over the barn (interview Jeff MacDonald, September 6, 2005).

19 Lifting stones also figured in the dynamics of courtship. Hugh “Oban” Gillis of Pinevale, Antigonish County, placed a huge rock at the entrance of his property stipulating that all prospective suitors had to be able to lift the rock off the ground in order to be able to court one of the Gillis girls (Cheng, personal communication, December 11, 17, 2010). A lifting stone featured in Rory MacDonald’s wooing of Anne, the daughter of Donald and Marcella MacDonald of Pinkietown, Antigonish County. Anne’s father refused to permit matrimony without testing Rory’s mettle and might. The following challenge was issued: the young suitor was to lift a large sandstone rock weighing 160 pounds (72.6 kg) situated at the back of the barn. In the end, brains allied with brawn as the youth returned furtively that night with a coal chisel, a mallet and rug and commenced carving away at the underside of the rock. In three hours, he had managed to chip away fifty pounds (22.6 kg) of stone chips, which he carefully concealed in the rug. The next day, he lifted the rock two feet (60 cm) high, managing to mask his ruse from Anne’s father who welcomed him into the family with a handshake (MacLean 1963: 16-17).6

20 Strong arms and broad shoulders were valued assets at such events as ploughing matches and burials. However, displays of physical strength can also be understood within the framework of identity construction, for they allowed certain individuals to affirm visibly their own relative standing within local hierarchies (interviews Rita Gillis, July 28, 2005; R. J. D. MacNeil, July 5, 2005; MacMillan, August 14, 2005). East River’s Big John Falconer was guaranteed to draw spectators whenever he stripped off his coat and vest, and rolled up his sleeves to issue a challenge “to any man within five miles around” (Grant 1947: 56). Daniel Rankin, “the strong man of Sutherland’s River,” also enjoyed a large measure of local fame for his “dead weight lift” of ten hundred pounds (450 kg) (Eastern Chronicle, March 25, 1924). It is not surprising that Billy MacLean of Cross Roads, Ohio, Antigonish Co., was sworn to secrecy when his sibling, Big Donald, ended up flat on his back following a tussle. No less than Big Donald’s social status within the community was at stake, so the brothers made a pact never to “reveal the exploit to any person” (MacLean 1963: 16-17).

21 During the era of open-voting in Eastern Nova Scotia and Cape Breton, elections provided an important outlet for physical strength, especially when passions were inflamed by fierce political loyalties and plentiful liquor. In this context, prowess could be displayed in an overt way or as an implied potential. During the 1830s, the McCoulls were summoned to one of the local hustings in Pictou County to enforce order during an election. According to the Rev. Robert Grant, “The very sight of them was enough to quell a riot” (Grant 1947: 10). The robust Anthony McCoull, outfitted in wooly homespun, bore an uncanny resemblance to a polar bear, while his brother, Robert, was often likened to the mythological hero, Hercules.

22 Community feuds, ethnic animosities, and personal grudges were also avenged and occasionally resolved through displays of physical strength. For John MacDonald of Williams Point, Antigonish Co., it was an affront to Celtic physical supremacy which aroused his combative impulses. Although having just returned from his legendary five-day trip in 1816 to Halifax, walking there and back (fording or swimming streams en route) and being fortified with bannock and rum, he found reserves enough to participate in a match against some local Irish inhabitants. Goaded on by a fellow Highlander, “See what those Irish lads are doing to us Scots; Tired as you are man, take you one or two refreshments and go out to what you can do,” MacDonald “tipped” the balance to vindicate “his own countrymen” (Macdonald 1959: 15). The Roman Catholics of Washabuckt and Protestants of Middle River and Big Baddeck often resorted to muscle to square off against each other during the 19th century. A myriad of other community rivalries peppered Eastern Nova Scotia and Cape Breton, such as the longstanding rows between the settlements of Big Judique and Little Judique, Grand Mira North and Grand Mira South, or Gabarus and Gabarus Lake, which invariably flared up at local dances. Pictou County was especially bedevilled by internal factions, as John Mackay noted:

23 Community reputations rose and fell on the physical might of their citizenry. For example, at one time, Christmas Island’s Macolm MacNeil had bragging rights on the Miramichi River, claiming the record for cutting more timber in a week “than any other man in the camps” (MacKenzie 1926: 91). Personal aggrandizement was not an end in itself for strongmen, for their achievements also simultaneously buttressed the glory of their communities. For this reason, strong men viewed themselves as champions of their respective locales, and stories about their pitched battles represented a vigorous expression of home place. These events were eminently tellable and memorable, and residents relished their chosen heroes’ victories. Angus McNeil, one of the “most noted of the strong men” of Piper’s Cove, was a magnet for onlookers when he responded to Big Donald MacDonald, a labourer on the St. Peter’s Canal, who threw down the gauntlet to the strong men of Grand Narrows and Iona (85-86). At the age of twenty, Alexander McDougall headed off to Ingonish, acting as a self-appointed proxy for his community, to “thrash” a “bully” who was harassing the seasonal fishermen from Christmas Island (32). East River’s Deacon McKay, proclaimed the “very personification of muscular power,” did not have to travel so far for his pound of flesh. One winter’s day, he found himself at Pictou’s Mason Hall wrestling William Allan, who had issued a challenge “to any bluenose within twenty miles, for a trial of strength and skill.” The Yankee blow-hard found himself trounced not only once but twice. Cheered on by his East River contingent of supporters, McKay “gained an easy victory” and delivered the parting shot, “I have strength enough yet to break every bone in your body” (Grant: 30-31). In Antigonish, the perennial town/county rift was manifest in an organized match between a Mr. McGibbon and John “the Blacksmith” MacLean, who was enlisted to defend “the honor of the county.” Held under some big elm trees (now Columbus Field) in the town of Antigonish, this contest ended with MacLean’s decisive victory, earning him the distinction of being “the strongest man” in Antigonish town and county (MacKinnon, personal communication, Oct. 28, 2012).

24 The tradition of the challenge adapted to changing times, as newspapers were enlisted as mouthpieces for a metaphorical “throwing down the gauntlet.” In June 1888, The Casket broadcast the formal challenge of school teacher Alexander MacDonald of Ohio, Antigonish:

25 The tradition of physical challenges continued into the 20th century. Hugh N. MacDonald again found himself the target of a rival strong-man. “Hoodie,” who practised medicine in Whycocomagh, Cape Breton, from 1892 until his death in 1932, was assailed at his surgery by a “braggart from the mainland,” who came with the express purpose of picking a fight. The “Pictou County bully” left quickly, helped on his way as a human projectile hurled over a fence (Sydney Post-Record, January 28, 1938).

26 Displays of physical strength also had a more recreational dimension, figuring prominently in an array of informal games, such as maide leisg (lazy stick) and leum a’ bhradain (the salmon’s leap), which were central to the cultural life of the region. 7 Before the introduction of organized athletics, such as the Highland Games, early settlers in Nova Scotia held “musters” or “fairs” where young men competed against each other in field sports, vying hotly for the honour of superior muscular strength. Most of those contests took the form of “pugilistic encounters” where opponents stood, “one side of a rope stretched between two stakes, in order to ensure that only fair blows were struck” (Macdonald 1959: 13). In the early days of Pictou County, West River hosted a field day where the East and West River and Green Hill men converged for “various trials of strength, with feats of agility, as leaping, throwing the stone, etc.” (Grant 1947: 56).

27 The stories of Eastern Nova Scotia’s real-life strong men and women possess a richness for both the folklorist and social historian, offering fresh insights into the inner workings of the community to which this lore belonged. It points to the fact that in the moral world of early Scottish settlers physical force was not to be deployed as raw power and uncontrolled fury to bully, tyrannize or abuse. The stories frequently reminded the reader, as well as the listener, that these specimens of superlative strength were not warring barbarians, but invariably people of benign and good-hearted dispositions. An early settler of the S.W. Margaree, Donald McVarish, a native of Moidart, Scotland, was a case in point. He incorporated “uncommon strength” as well as the “many of the qualities of the lamb”—a force to be reckoned with but not “dreaded” (MacFarlane 1896). Broad Cove’s Big Ranald MacLellan embodied a similar paradox, for his massive hands, which could bend horseshoes like putty, handled a bow and fiddle with gentle finesse. Inverness County historian J. L. MacDougall clearly differentiated between brute force and physical exertion, noting, “And the beauty of it was that every one of these men took pains to show that his special strength and power were given to help, rather than to hurt the neighbors” (MacDougall 1972 [1922]: 239). Current tradition bearers reiterate this depiction of venerated strong men as being quiet, peaceable, and even child-like, motivated by a unified sensibility that physical strength should be tempered by mercy and fairness (interviews Peter Jack MacLean, July 5, 2005: MacMillan, August 14, 2005; Anderson, August 17, 2005). As a cultural emblem, strength was most prized when it symbolized such positive traits as honourable motive and heroic conduct.

28 Reflecting an older social ethos and a pre-modern view of the world, physical force was justified in the following contexts: self-defence, neighbourliness, preservation of human life, avenging wounded pride, and defending personal/family and community honour. Under these circumstances, acts of strength served as a legitimate tribunal for redressing grievances and securing personal and community justice. This attitude explains why, for example, the published account of Allan McNeil’s brutal encounter with a Cape Breton Acadian lacks any note of censure. The thrashing, which left McNeil’s opponent unconscious with blood flowing from his ears, was deemed a valid confrontation, that is, it was deserved and defensible. Certainly, McNeil’s reputation was not tarnished or even diminished by the violence of the altercation. The Acadian, it seems, got his proper comeuppance. It was pronounced “...that this incident taught him a lesson as to the dangers of insulting a Scotchman, and it is said also that he governed himself accordingly ever afterwards” (MacKenzie 1926: 87).

29 Old age was not regarded as an impediment to accomplishing feats of physical strength. Nineteenth-century obituaries had a penchant for listing the physical feats of those who had defied the infirmities of old age. The death notice for Malcolm McMillan of Catalone, who died at 101 years of age, expounded on his recent activities, most notably sewing a pair of mill-cloth trousers for himself. The autumn before his death, the physical stamina of this North Uist native had shown little evidence of ebbing. In fact, he had mowed hay alongside his son, grandson and great-grandson, completing a day’s work which was “equal, it is said, to that of the best of them” (Presbyterian Witness, December 15, 1888). Nineteenth- and twentieth-century feats of strength stories from Eastern Nova Scotia and Cape Breton are devoid of ageism. Instead, one’s advanced years typically enhanced the status of exploits in this realm. In 1910, The Free Lance of New Glasgow recorded the achievement of a 95-year-old woman who had once ridden horseback alone, from Green’s Brook to Barney’s River, through dense woods for five or six miles (Fraser 2013: 405). The redoubtable Alex McKay of Pictou, even after a backbreaking life as a river driver and lumberman, showed remarkable vivacity in his eighties and nineties, when he could still “mow his swathe with young men” (Patterson 1877: 291). Malcolm Robertson, who emigrated to Whycocomagh from Scotland in 1830, also belonged to the pantheon of aged strong men. He walked to Albion Mines in the 1860s to spend his 100th birthday with his son (Kirincich 1990: 84). Jimmy Mick Sandy MacNeil of Benacadie Pond relates a story about an elderly strongman who rallied on his deathbed to oust from his bedroom a potential antagonist, bellowing: “You won’t put me down today. I’ll put you down!” (interview Jimmy Mick Sandy MacNeil, August 9, 2005). Neither old age nor strenuous work drove Englishtown’s robust Torquil MacLean into retirement. “Built like a wrestler” and as “strong as an ox,” the octogenarian operated the ferry boat across St. Ann’s Harbour, up until his death in the 1920s (Morrison 1973: 6). Today, Cape Breton’s Englishtown ferry bears MacLean’s name, thereby commemorating his heroic achievements and serving as a locus of memory.

30 Eastern Nova Scotia and Cape Breton’s stories about feats of strength reveal other distinctive attributes. For example, bodily strength was not necessarily coterminous with physical size (in other words, a person of average build could be mighty and hence revered). Moreover, strength was regarded as a God-given gift with symbolic and practical value, and as such it was not to be used for profit. In the mid-1850s, the parents of the Giant MacAskill of Englishtown cautioned his manager to display only his size rather than his strength on the American freak show circuit. The parents of turn-of-the-century Boularderie boxer, Jack Munroe, opposed his career in the ring because it exploited his physical strength for commercial gain, not as a force for good.

31 It is also significant that strength, as noted earlier in this article, was not framed in terms of gender. This distinguishing feature of the Gaelic oral tradition was not the norm in other parts of 19th-century Canada, where physical feats were equated singularly with masculinity. According to Kevin Wamsley and Robert Kossuth (2000: 411), “the bodily vigor of women, although a reality in daily rural experiences, does not hold a place of prominence in the historical lore of physical strength” in Central Canada. Similarly, according to Podruchny, the French-Canadian voyageurs who inhabited the hyper-masculine world of the fur trade, exalted feats of superhuman strength and endurance as the sine qua non for consolidating male reputations. As a matter of course, voyageurs’ bear tales omitted “women’s brave deeds,” appropriating this version of heroism as an exclusively masculine ideal (Podruchny 2004: 13). However, in the collective memory of Scottish Eastern Nova Scotians and Cape Bretoners, men had no monopoly on physical hardiness, and passivity and dependency were not glorified as female virtues. French Road’s Malcolm McCormick, we are told, was proud of the “physical endurance and strength” of his barrel-touting wife (MacMillan 2001: 628). In their reminiscences, our tradition bearers readily acknowledged the muscular vigour of their female forbears, indicating that they performed much more than just cameo roles in this storytelling corpus.

32 Social class, however, appears to have a subsidiary function in feats of strength stories. Proving one’s physical mettle was calculated in terms of outcome not income and, therefore, feats of strength stories embrace a socioeconomically diverse cross-section of celebrities, from Bishop William Fraser, an early 19th-century Antigonish bishop, who could bend horseshoes with his bare hands, to “Big” Jack MacKinnon of early to mid-20th-century Cape Breton, a reclusive social misfit who became a local referent for indiscriminate strength (Nilsen 1988: 62). “The Clouter,” as he was called, is reputed to have transported barrels of provisions on his back from Sight Point up Cape Mabou, to have “stiffened” opponents with near lethal blows, to have wrestled with telegraph poles, and to have slit the throats of unruly cows while locking his arm about their necks in a vice-grip (D. MacInnes, personal communication, November 18, 21, 2011; interviews Peter Rankin, July 7, 2010; Anna MacKinnon, August 29, 2010). The stories about clerical powerhouses constitute a distinctive subset of strength narratives. Bishop Fraser (1758/1759-1851) was renowned “among the old folk” for his epic strength, while the Rev. James MacGregor (1759-1830), the indefatigable six-foot tall Presbyterian cleric, inspired adulation for logging countless hours and miles to minister to his dispersed flock in mainland Nova Scotia, Cape Breton, and Prince Edward Island (Nilsen 1997: 171-94). These clerics have their 20th-century equivalents in Father Angus R. MacDonald (1868-1953), Christmas Island’s longtime pastor whose muscular interventions helped break up fights, the Rev. Charlie MacDonald (1905-1990), a Cape Breton Presbyterian cleric, who with robust ingenuity shoed recalcitrant horses, and Father Dan R. “Dempsey” Chisholm (1899-1964), an imposing, big-framed man, nearly six feet five inches (2 m) in height, whose athletic feats at the Antigonish Highland Games and on the Ohio Tug-of-War team attracted a widespread fan base throughout the county (MacDonald 1979: 46-48; interview Peter Jack MacLean, July 5, 2005). Some locals can still recall the priest, who shed both coat and collar to compete, and for the marathon walks, pre-dating his ordination, which took him from the lumber camp to mass each Sunday and back, a distance of forty miles (64.4 km) (MacPherson 1965: n.p.; Stanley-Blackwell and MacLean 2004: 226).

33 Upon close examination of our fieldwork and published settlement narratives of Eastern Nova Scotia and Cape Breton, one is instantly struck by the prevalence of strength stories. It was the everyday men and women of muscle who captured the affection of the region’s storytellers, who asserted the feats of their subjects quite apart from those of MacAskill, not as a “corrective” but as a “coherent, alternative historiography” (Beiner 2004: 201). Although more real than imagined, these stories, charged with social significance and meaning, are far more than mere statements of fact. They are essentially about settler survival, affirming the Scottish settlers’ conquest of a landscape of vast distances, rocks, trees, and wildlife, asserting a sense of social hierarchy in the living world, and representing an internally directed dialogue among community members, thereby reinforcing community values and social norms. As stories of individual physical achievement, which implied collective Highland cultural prowess, they must have served as a source of validation for many Nova Scotian Scots. Similarly, the stories about men outperforming their farm animals perhaps compensated psychologically for the humiliation of the forced evictions of the 18th and 19th centuries, which witnessed human beings supplanted by sheep. Podruchny contends that French-Canadian voyageur culture regarded physical superiority as a mark of distinction and source of “symbolic capital” (i.e., social power and prestige)—an eminently relevant form of social currency at a time when material possessions were limited in number and significance (Podruchny 2006: 185). Such explanatory insights are directly relevant to Eastern Nova Scotia and Cape Breton, where Scottish immigrants used their bodies to proclaim and bolster their personal and public identities. Their fame was a collective product, and the public inferred heroic traits from their physical accomplishments. The ordinariness of these home-spun heroes did not dim their achievements, and their stories preserved the memory of the past and excited emulation among those who listened to or read about their wondrous exploits.

34 Although the narratives about their feats may look prosaic alongside the more elaborate wonder- and hero-tales, this fact should not detract from their historical value. These stories were the stuff of mythmaking, and the physical feats of the people were bound up in the history of their communities. Moreover, they represent an important branch of the Gaelic oral tradition and are part of the communal storehouse of the people’s past. In short, they belong to what folklorist John Shaw has described as “the less tangible but equally real form of stories, songs, music, dance, oral history, language and custom and belief that have been enthusiastically transmitted over centuries by the common people” (Shaw 2007: xi).

35 At the end of the 19th century, feats of strength stories in Eastern Nova Scotia started to undergo a profound transformation. This evolution in story format was precipitated by the inroads of industrialization and the development of consumer-oriented spectator sports in Eastern Nova Scotia. As stated by Rosemarie Garland Thomson, modernization and mechanization “reimagined,” “reshaped,” and “relocated” the human body, creating what she labels as “new somatic geographies” (Thomson 1996: 11). The traditional feats of strength stories about stones and barrels, which were reflective of a pre-industrial, agrarian society, were recycled into the present to incorporate more modern equivalents, such as car motors, car transmissions, tractor tires, gasoline barrels, railway ties, drive shafts, automobiles, railway spikes, telegraph poles, and coal boxes—objects that were more representative of an industrialized society. Thus, it is recorded that Red Angus MacEachen from Brook Village, “as an old man,” hoisted a car from a bog; that his equally burly MacLellan cousin allegedly “burst the seams of his pit boots lifting a box of coal back onto the track in Glace Bay”; that Alex C. P. R. MacDonald could “lug a stout twenty-five-foot pole into a wooded right-of-way and set it single-handed”; and that steelworker Stephen Archie MacKinnon of Highland Hill lifted and “turned a rail weighing hundreds of pounds” over a stand, which was later painted to commemorate the feat (MacKenzie 2003: 135, 117; interview Maxie MacNeil, September 8, 2005).

36 By the turn of the 20th century, there was a further discernible difference in physical strength stories, as these feats were increasingly staged in sports rings rather than in the barnyards and the woods. The muscular hero of the rural settlements mutated into a new variant, which foregrounded instead the muscular male athlete. By the late 19th century, the fall fair and Highland games were the premier venues for organized competition among Eastern Nova Scotia Scots. The strong man events, such as the caber toss, stone put, hammer throw, and tug-of-war contests, ritualized displays of muscular potency. In an adulatory tone, The Casket reported that the strong man contestants at Antigonish’s Highland Games were “the stuff of which heroes are made” (July 30, 1908). Strength was also increasingly seen as a commodity to be bought and sold and mediated by promoters, managers, and trainers. And yet, despite these differences, the new strong man hero continued to exemplify aspects of the moral code of earlier generations. Displays of strength were not a blatant celebration of violence but still carried with them certain obligations, namely honour and courage. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the men who were revered among the Scots of Eastern Nova Scotia and Cape Breton were “champion pugilist” Jack Munroe, the “great, big, rough gladiator” from Boularderie, and Simon Peter Gillis, the world heavyweight hammer thrower from Gillisdale, Margaree, who boasted the “extraordinary feat” of a 12-pound (5 kg) hammer throw of 210 ½ feet (64 m) (Sydney Record, December 15, 1903, March 3, 1904, March 12, 1907; Gillis n.d.: 72). Sharing top billing were Donald “Judique Dan” MacDonald, who fought 945 bouts during his career as a professional wrestler and secured the title of 1912 World Middleweight champion, and Antigonish boxer, Hugh J. MacKinnon, who garnered in the U.S. an impressive assortment of championships in middleweight and welter-weight categories (Making a Difference 2000: 16; MacKinnon, Hugh J. file).

37 The spirit of the dogged foot travellers of the pioneer era seemed reincarnated in the athletic John Hugh Gillis, who set out in January 1906 on a record-setting transcontinental hike, which took him from North Sydney to Vancouver in nine months (Hart 2006 [1906]). The muscular vigour of Whycocomagh’s Dr. Hugh “Hoodie” MacDonald, a world-class athlete whose strength was calculated to equal “nine or ten men,” also swelled with pride the chests of Cape Bretoners. They relished details about his bare-fisted altercation with John L. Sullivan, which left the American boxing great sprawled unconscious on the floor (Whycocomagh Gael ca. 1945: 9).

38 Cape Breton’s attachment to boxing has its roots in the late 19th century but, by the 1920s, it had become a full-blown love affair. So-called “fight talk” became the staple of storytelling, most notably in the industrialized areas of Cape Breton. There, boxing heroes were lionized as Cape Breton poet, Dawn Fraser, once enthused: “Lord, but we love a fighting man.” (Fraser 1992: 51). Many early Cape Breton boxers worked in local industries, especially the mines, where manliness and physical strength were regarded as one and the same. In this workplace, courage, manual labour, and endurance were the core masculinities. John DeMont’s Coal Black Heart captures the essence of this culture, writing: “The very air felt different when the colliers—role models, heroes, elders, all in one—strode down the streets. Songs were written about men like these. Who could cut the most coal? Who was the strongest? Who could stand the gaff? ... Legends were born in these young places searching for their own unifying stories” (DeMont 2009: 140). “Big Frank” McIntyre, born in Glengarry, Big Pond in 1878, was “known in the pit for his strength,” a distinction best illustrated by his ability to single-handedly pick up a punching machine, used for drilling coal; a feat that usually took two or three men (interview Jim McIntyre, October 31, 2010). Little wonder that an industry such as coal mining, which challenged men’s sense of autonomy and mastery over their own bodies, precipitated a new version of the strong man whose heroism was measured in terms of his slugging fury in the ring and the power of his punch. Late 19th- and early 20th-century Cape Bretoners were fiercely proud of these star athletes. Senior miners would organize their shifts around fight night, looking forward to crowding into “smoke-filled” rinks, theatres, and forums doubling as boxing arenas (Young 1988: 31). Localism still prevailed and, like the strong men of the past, boxers fostered hometown pride and ignited an intense possessiveness, as local communities such as New Waterford, Glace Bay, and Whitney Pier vied amongst themselves as well as with outsiders, i.e., mainlanders, for the palm of physical superiority.

39 The new version of the feats of strength story diverged from its predecessor in several significant aspects. First, the sites of physical strength, especially those related to “occupational communities” such as mines and steel plants, were now exclusively male (Myers 1997: 4, 34). As masculine proving grounds, they showcased a virilized hero and marginalized, if not completely abandoned, the once popular stories of female strength. Secondly, many of the strong man idols of this later period were emphatically working-class heroes, especially during Cape Breton’s class war of the 1920s. For miners and their families, locked in mortal combat with the coal companies, boxing was a “cultural metaphor” (MacDougall 2010: 150). “Putting up a fight,” “not backing down,” “having heart,” and “standing the gaff” were not only practical survival techniques for miners but the hallmarks of a good boxer (Davey and MacKinnon 2016: 164). Thirdly, the vocabulary of tropes for describing male strength was now derived from industrial technology rather than wild or domesticated animals. Hence, the performances of strong men were deemed analogous to “human cranes” or “magnificent physical machines” (MacKenzie 2003: 135; Graham 1956: n.p.). Fourthly, the new version tended to privilege commercialized displays of physical strength and to substitute a more diverse image of ethnicity for the traditional homogeneous Scottish one. Whether one was Jack Carbone, the Glace Bay “Bear Cat,” or Johnny Nemis, an Italian miner from New Waterford, or Bernard “Kid” O’Neill of Sydney, or the North Sydney native, Jack McKenna, “one of the toughest boxers to ever come out of Cape Breton,” the hometown crowd did not differentiate on the grounds of ethnicity when their strongman heroes entered the ring (MacDonald 2009: 134-180; MacDougall 2010: 11). Nor did fans fixate on whether these sports figures were clean-living or hard-living—what mattered ultimately were their hard-hitting deeds of prowess (MacDonald 2009: 148-53). This brand of the feats of strength story was a faithful portrait of the new realities of the typical Cape Breton industrial town, which was fast becoming a mosaic of multiple ethnicities.

40 In conclusion, it should be noted that the new version of the strong man story did not silence the traditional rural narratives about feats of strength. Deeply embedded in values and traditions, the latter survived the assaults of language shift, urbanization, and industrialization. Although a product of a largely oral, pre-industrial culture, this story genre proved durable enough to spin off in the colliery districts of Cape Breton (where the oral tradition of song and story still survived) a separate strand of strong man narratives, which became part of the industrial folk culture of Eastern Nova Scotia (Frank 1985: 204). At times, the two story traditions appeared to merge, as demonstrated in Dawn Fraser’s classic lines: “We like ’em rough and tough and clean. / But never yellow or sore or mean. / Give us a man who will fight like Hell / And we’ll give you the gold To pay him well” (Fraser 1992: 51). Pre-modern and modern variants of these stories coexisted in the memories and imaginations of Eastern Nova Scotians and Cape Bretoners, at least into the 1940s, as they continued navigating the rural-industrial continuum. In his The Highland Heart in Nova Scotia, MacNeil captured the essence of this fascinating duality among strong heroes when he wrote:

41 Even today, in Eastern Nova Scotia and Cape Breton, feats of strength stories possess emotive power and enjoy remarkable longevity as a manifestation of intangible cultural heritage. Related with sincerity, credulity, and spontaneous directness, they still form part of the orally transmitted repertoire of tradition bearers. These stories also continue to live on in family oral histories and published genealogies. Occasionally, this local story lore resonates in obituaries such as “Lame Angus” MacEachern’s death announcement in 1985, which identified his lethal attack against a large bear with an old car driveshaft as “one of his best-known feats of strength and determination” (The Casket, July 24, 1985). And this lore retains a tangible presence in such objects as Big Beach’s dutifully painted lifting stone where feats of strength were once performed (Fig. 1) and the licence plate of an Antigonish County resident, on which is emblazoned the word “BEARMAN.”

The authors would like to acknowledge the financial support of the Centre for Regional Studies, St. Francis Xavier University, which provided much of the research funding for this project. We are especially grateful to Meaghan O’Handley for her research assistance and to the invaluable contributions of the following individuals: Henry and Catherine Anderson, John D. Blackwell (St. FX University), David Brown, Diane Cameron, Ron Caplan, Marlene Cheng, Gertie Chisholm, Willie Chisholm Angie Farrell, John Fraser, Willie Fraser, Jocelyn Gillis (Antigonish Heritage Museum), Rita Gillis, Florence Helm, John Johnson, Dr. Guy Lalande (St. FX University), Angus “Johnnie Allan” MacDonald, Colin MacDonald, Charles “Sharkey” MacDonald, Dr. Daniel A. MacDonald, Jeff MacDonald, Joe MacDonald, Ronald A. MacDonald, Sandy and Theresa MacDonald, Fr. Malcolm MacDonell, Sister Margaret MacDonell, Clare MacEachern, Mary MacEachern, Dr. Dan MacInnes (St. FX University), Sadie MacInnis, Anna MacKinnon, Annie MacKinnon, Dr. Ron MacKinnon, Cecilia MacLean, John MacLean, Peter Jack MacLean, Stacey MacLean, Murdock MacLennan, Karen MacLeod, Fr. Allan MacMillan, Anne Marie MacNeil (Beaton Institute), Jimmy Mick Sandy MacNeil, John H. MacNeil, Maxie MacNeil, Michael Jack MacNeil, Mickey John H. MacNeil, Murdock MacNeil, Roddie John Dan MacNeil, John Stephen MacQuarrie, John Marshall (John Marshall Antiques), Jim McIntyre, Dr. Carolyn Podruchny (York University), Sadie Poirier, Daniel Rankin, Effie Rankin, Peter Rankin, Kathleen Reddy, Beatrice Smith, Hughie Stewart, Peggy Thompson, and Jim Watson (Highland Village Museum).