Articles

Black History Month Programs:

Performance and Heritage

Abstract

Implications embedded in Black History Month programs access desires for cultural recognition of African American contributions and history within the United States. Equally important at these events is the implicit furthering of knowledge and connection to the past and the sustainability of African American heritage and culture. Concepts of “home” as historical, national, and individual community, infuse each performance and support and encourage connections that in turn insist on the removal of myopic considerations of cultural subjectivity and sustainability. Black History Month programs revision “home” through counter-stories of Blackness in America and American-ness in Black America.

Résumé

Les programmes du Mois de l’histoire des Noirs répondent implicitement aux désirs de reconnaissance culturelle des contributions et de l’histoire des Afro-américains aux États-Unis. Lors de ces évènements, l’approfondissement implicite de la connaissance, la relation au passé et la durabilité de la culture et du patrimoine afro-américains sont tout aussi importants. Les concepts de « chez soi » en tant que communauté historique, nationale et individuelle inspirent toutes les séances et soutiennent et encouragent des connexions qui, en retour, insistent pour que l’on abandonne les considérations à courte vue au sujet de la subjectivité culturelle et de la durabilité. Les programmes du Mois de l’histoire des Noirs revisitent le « chez soi » au moyen de contrerécits portant sur le fait d’être Noir en Amérique et d’être Américain dans l’Amérique noire.

1 The yearly commemoration of Black History during the month of February speaks to desires of African Americans1 for cultural heritage recognition across American social, intellectual, political, and financial landscapes. African Americans have historically been relegated, collectively and individually, to secondary positions of power within the United States, and the Black History Month program is an ongoing reminder of the impact of African American presence, and its foundational role in the nation’s history.

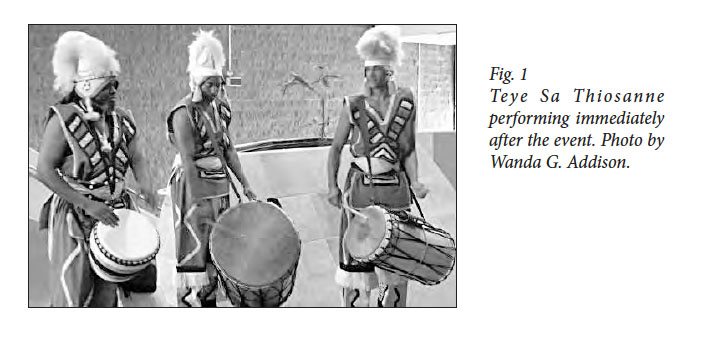

2 My focus in this article is on an event called Telling Stories of Black History, one of several events that occurred during the commemoration of Black History Month in San Diego, California, in February 2013. The event recognizes and offers entry into intangible components of African American cultural heritage. I will examine two performances from this event: the event’s opening remarks by Mzee Kadumu Moyenda offer the frame of oral tradition that the remainder of the program will expand upon; and the storytelling of the Black Storytellers of San Diego, Inc. The two stories focus on heritage connection and legacy-building between youth, adults, and ancestors. On February 13, 2013, an audience of approximately 125 participants, made up largely of African Americans and ranging in age from young adults to elders, attended Telling Stories of Black History, a Black History Month program held in the Educational Cultural Complex Performing Arts Theatre, which is part of San Diego Continuing Education and San Diego Community College District. The event supports a collective experiential journey through traditional African drum calls and sharing in songs and storytelling. It acts as a catalyst and opportunity to extract from the realities of daily life remembrances of who we are, where we have been, and with whom we are connected, opening gates to yesterday and tomorrow.

3 Black History Month programs resituate “home” in a different type of remembrance. They unmask the hidden or repressed histories of African Americans. That is, they take up Bilinda Straight’s challenge to “strategically lay claim to the idea of home as a way of asserting their right to home and a secure identity” (2005: 1). Straight is not only speaking about home as place but as idea, a “discursive production” that “elicits enigmatic longing, control, or outright violence” (2). Home is a physical, tangible place, generally trusted as something real in space and time. In a nation-state, however, the most obvious and privileged notion of home defines national identities: I am American (of America); I am not English (of England). Home, then, grows into the place which moulds self-identity along particular cultural lines. Telling Stories of Black History re-visions home and foregrounds African American heritage through counter-stories of Blackness in America and American identity in Black America. African Americans are positioned between two modes of existence. One points toward inclusion within mainstream American society (nation-state) while the other addresses internal realities of being African American within that society. For the latter, I use the term nation-home. Those two, at times conflicting, poles exist as home bases that are points of negotiation, similar to Du Bois’ idea of double consciousness2 defined by Sexton as “the African American’s awareness of possessing two souls: an outward self based largely on how whites perceive him and an inward self that he comes to realize as his truer self” (2008: 778). Perceptions of nation-home recognize the embedded conflict between external characterizations of internal reality to interject self and community into the backdrop of collective national identity creation, and are always filtered through a historical perspective.

4 Part of the goal of Black History Month programs is to reposition the individual and group to their history. Contemporary Black History Month programs generally have two purposes: to educate Americans about African American history and African American contributions to the American societal framework, and to celebrate African American identity. This commemoration has its origins in the work of Dr. Carter G. Woodson. In 1926, Dr. Woodson established Negro History Week “to increase awareness of and interest in black history among the black masses” (Goggin 1993: 84). This week-long educational celebration “helped blacks overcome their inferiority complex and instilled racial pride and optimism” (84). For Woodson, this was one of the most important aspects of the week-long commemoration. If Black Americans no longer had a strong understanding of or connection with their heritage, then they would profoundly feel the impact of other’s oppressive perceptions of them. If, however, they were knowledgeable of the powerful legacy of African Americans, they would be better able to withstand such damaging oppression remembering the strength of their ancestors and understanding that strength was within them as well.

5 Woodson, a noted African American teacher and historian, understood the “uplifting power of education” for African Americans, specifically, “accurate education about the black past” (xiv). In the initial one-week long celebration, Woodson “envisioned the study and celebration of the Negro as a race” outside of the confining posture of “producers of a great man,” such as Frederick Douglass (Scott 2011). Negro History Week was rechristened Black History Month in 1976, maintaining its focus on the education of Black Americans about their history. Telling Stories of Black History reconnects to the legacy of the month-long commemoration, focuses on teaching Black Americans about their heritage, and builds upon Woodson’s legacy, enacting images of “black in America” that interrogate societal visions of African American self and the American cultural landscape.

The Program

6 In February 2013 in San Diego, California, several events took place celebrating Black History Month. Each of these events had one particular focus: showcasing African American presence in the United States. Programs included performances by African American classical pianist Cecil Lytle, screening of Josephine Baker films and a documentary on connections between early 20th-century German racism and Jim Crow America, various musical performances encompassing jazz, a gospel choir, reggae, Afro-Cuban and selections of Black female singers such as Billie Holiday, and history of African American Mountain Men in the 1800s western United States.

7 Of the numerous programs, Telling Stories of Black History was unique with its primary focus on narrative and the practice of African American oral tradition. This focus is representative of breaking the silence and speaking oneself and heritage into the forefront. Black History Month and its accompanying programs are a direct assertion of power, “a total structure of actions brought to bear upon possible actions ... a set of actions upon other actions” (Foucault 1982: 789), and thus speak against historical claims over African American reality. Black History Month programs act to disrupt the hegemonic frame by interjecting foundational knowledge of African American experiences and heritage. Such intentional cultural performances are acts of power that assert counter-narratives, foregrounding things like oral and visual culture of Black history against the dominant text-based narratives.

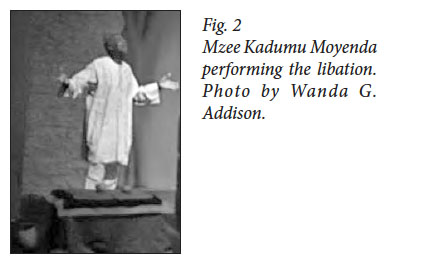

8 An early striking moment in the program was its captivating opening, a rhythmic drum call performed by the West African Drum and Dance Company Teye Sa Thiosanne. Teye Sa Thiosanne—Keepers of the Tradition—took the stage wearing traditional African dress of green, yellow, and black and each of the three drummers donned traditional headgear while playing a come-to-meeting drum call (Fig. 1). Following this captivating opening, Mzee Kadumu Moyenda, a member of the Black Storytellers of San Diego, Inc., took the stage to offer a formal greeting. Moyenda noted the drum call presented by Teye Sa Thiosanne was reminiscent of those traditionally performed in several African cultures to get the attention of community members, call them to assembly, and bring them together. Moyenda’s greeting was followed by his offering of the libation (Fig. 2). He stood before a table that was approximately one metre tall, covered with a green cloth upon which rested another piece of green, black, and red fabric, and two small wooden cups, one slightly larger than the other. On the floor next to the table sat a somewhat larger wooden vessel. Moyenda began:

Moyenda & Audience: Ashe

M: (a) Like to give praise and thanks to our future, to those yet to be born and to the youth. (b) May they continue building the foundation based on truth and justice, and more importantly, that they do it in the correct way.

M & A: Ashe

M: May the god/goddess of our ancestors hear us.

M & A: Ashe M: May our ancestors hear us.

M & A: Ashe

M: And may our future hear us.

M & A: Ashe

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2

9 Moyenda explained the significance of the libation as similar to a formal invocation at a church service. It gets everyone “into the right spirit. What’s important is we all come together, especially on these occasions, in one spirit.” The aspect of moving forward in one spirit is mirrored in the narrative frame of the libation. While Moyenda led the libation, its design was set to call all hearers together on one accord and thus reflect oneness, thereby framing Moyenda’s specific performance and simultaneously setting up the frame for the remainder of the program. The libation in its entirety offered a sense of progression and perpetual movement forward.3 In turn this was reinforced at multiple points in the narrative, allowing overarching understanding of the goal as well as avenues into various sections for maximum personal connection of the individual and their place within the broader framework of history and cultural heritage. Repetition held the libation together and the form mimicked and reinforced the method. Narratively, it was a rhetorical strategy that served linguistically as indicative of what he was calling upon others to do in their lives.

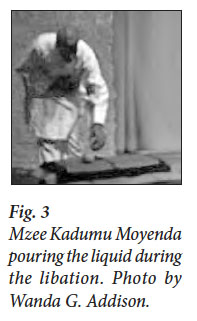

10 After each of his calls—lines 1 and 3—and at the utterance of “Ashe” that followed each, Moyenda poured liquid from the smaller wooden vessel at his left hand into the slightly larger one on his right (Fig. 3). Again after each of his calls in lines 5, 7, and 9 and at the audience response of “Ashe,” he poured liquid from the wooden vessel at his right hand into the larger vessel sitting on the floor. With the size progression of each vessel—small to medium to large—Moyenda was visually representing the reciprocal continuity from youth to adult to ancestor.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3

11 His beginning acknowledged this legacy by grounding the pronouns as action. “They” referenced the ancestors of which he later spoke. Not only were historical figures as ancestors captured under this pronominal usage—people like Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth, and Martin Luther King, Jr.—but personal ancestors were included as well. The first sentence was a reminder for each audience member to look to their own familial history to discover what the “theys” in their families have done. Likewise, it called upon these same audience members to contemplate the legacy builders in their communities, thus identifying points of connection. “They,” “us,” and “we” act to bring recognition to a forgotten or unknown legacy across the span of African American history while calling on the “we” and “us” audience member to acknowledge the receiving end of this legacy with an unspoken expectation of looking to the future and the legacy wrought by those who come after.

12 The libation was woven together like a tapestry, giving honour and forging expectation. In line 3a when Moyenda gave “praise and thanks to our future, to those yet to be born, and to the youth,” he reiterated the connections of heritage, merging them with focus on “we” and “us” who are expected to carry it forward in self and community: “our future” who are “yet to be born,” and “the youth,” who were present—physically in the room as well as in the community. He was speaking not only to the youth in the room; equally important, Moyenda was also speaking to the adults in the room charged with shaping the lives of youth and ensuring knowledge of heritage remain before them. Line 3b offered a call to action on sustaining their cultural heritage. They are to “continue building the foundation based on truth and justice” so that they will continue the circularity of honouring ancestors by sustaining cultural heritage connections with the past and laying foundations in their paths for the “yet to be born” future. Through these lines, Moyenda suggested to younger audience members that they do not stand alone in deeds or actions. A ripple effect is created which can disrupt or strengthen what they pull from the past for themselves and for the future of others.

13 The program was embedded with framing cues that instruct audience members not simply on interpretation but also action, by recalling the suggestive action embedded in the cultural practice of call and response. The overarching frame was remembrance of history and ancestors. Implicit in this was an emotional connection which drives action. Lines 5, 7, and 9 repeat the call to cultural continuity. Moyenda employed significant repetition to strengthen the message, bringing full circle the libation and mirroring sustainability through intangible cultural heritage. The chorus in each line takes a “may/our /hear us” format that linguistically frames the event. As Bauman notes, “every act of communication includes a range of explicit or implicit framing messages that convey instructions on how to interpret the other messages being conveyed” (Bauman 1992: 45) in the remainder of the event. The parallelism embedded across the three lines acts as a “device of cohesion” that supports “discursive continuity” (Bauman 1993: 190) and reflects the cultural continuity set out in the event. Audience members were called to view the event as a connection to the past through memory, a call for remembrance of all that had transpired before and those individuals whose independent and collective actions helped Black Americans. Likewise, it was an insistence on recognition of the lineage of action which awaits the youth and those yet to be born, the continuity of what is given, received, and given in return—the concept of paying it forward.

14 Moyenda built into the libation formal call and response aspects in the repetition of “Ashe.” He offered verbal affirmation with expectation that a response will follow, dissolving any barriers between audience and performer. Each utterance of “Ashe” by Moyenda was followed by a short pause. Here, the audience was elicited, through silence, for a response and one was returned, symbolic of standing in agreement and acceptance with the words and sentiment of the libation. This was similar to the “Amen” offered during many church services when the congregation verbally stands in agreement with the minister’s words. At this point, the audience was removed from a place of static partakers and thrust into the role of co-makers in the performances to follow, thus acknowledging ownership of the event. Such active audience positioning reinforces “the ongoing shaping of the context of social interactions among real individuals” (Sawin 2002: 33), a resultant goal of Black History Month programs through reflective and reflexive gateways. These programs counteract the overarching “verbal-ideological world” (Bakhtin 1981: 270), which has historically positioned Black Americans within a sphere outside of codified mainstream American cultural experiences. Through such distinct separations, knowledge of self is deemed complete without interaction with those outside of a given cultural domain. Uniformity does not encourage reflexivity but “performances are, in a way, reflexive” (Turner 1988: 81) since they reveal self to self, whether performer or audience.

15 Each member of the audience was implicitly invited to call upon their personal mosaic as they internalize their reactions to and experiences of each segment of the program. A personal mosaic is “a way to organize your life ... of thinking about the world” to construct, reconstruct, and “recom-pose a unity” (Williams 2008: 31) across Black diaspora and multicultural American borders. The storytelling performance during Telling Stories of Black History acted as a “reflexive instrument of cultural expression” (Bauman 1992: 46). The storytelling or history choral reading as performed by storytellers from the Black Storytellers of San Diego, Inc.—BSSD—consisted of two segments: The Middle Passage, a reinterpretation of Robert Hayden’s poem (page 6) and the story of the people who could fly. Seven storytellers, each wearing African-inspired garments of white, gold, and/or black, took the stage (Fig. 4).

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4

“Middle Passage” by Robert Hayden (excerpt)

Jesús, Estrella, Esperanza, Mercy:

Sails flashing to the wind like weapons,

sharks following the moans the fever and the dying;

horror the corposant and compass rose.

Middle Passage:

voyage through death

to life upon these shores.

“10 April 1800—

Blacks rebellious. Crew uneasy. Our linguist says

their moaning is a prayer for death,

ours and their own. Some try to starve themselves.

Lost three this morning leaped with crazy laughter

to the waiting sharks, sang as they went under.”

Desire, Adventure, Tartar, Ann:

Standing to America, bringing home

black gold, black ivory, black seed.

Deep in the festering hold thy father lies,

of his bones New England pews are made,

those are altar lights that were his eyes.

Jesus Saviour Pilot Me

Over Life’s Tempestuous Sea

We pray that Thou wilt grant, O Lord, safe passage to our vessels br/inging

heathen souls unto Thy chastening.

Jesus Saviour

“8 bells. I cannot sleep, for I am sick

with fear, but writing eases fear a little

since still my eyes can see these words take shape

upon the page & so I write, as one

would turn to exorcism. 4 days scudding,

but now the sea is calm again. Misfortune

follows in our wake like sharks (our grinning

tutelary gods). Which one of us

has killed an albatross? A plague among

our blacks—Ophthalmia: blindness—& we

have jettisoned the blind to no avail.

It spreads, the terrifying sickness spreads.

Its claws have scratched sight from the Capt.'s eyes

& there is blindness in the fo’c’sle

& we must sail 3 weeks before we come

to port.”

What port awaits us, Davy Jones’

or home? I’ve heard of slavers drifting, drifting,

playthings of wind and storm and chance, their crews

gone blind, the jungle hatred

crawling up on deck.

Thou Who Walked On Galilee

“Deponent further sayeth The Bella J

left the Guinea Coast

with cargo of five hundred blacks and odd

for the barracoons of Florida:

“That there was hardly room ’tween-decks for half

the sweltering cattle stowed spoon-fashion there;

that some went mad of thirst and tore their flesh

and sucked the blood:

“That Crew and Captain lusted with the comeliest

of the savage girls kept naked in the cabins;

that there was one they called The Guinea Rose

and they cast lots and fought to lie with her:

“That when the Bo’s’n piped all hands, the flames

spreading from starboard already were beyond

control, the negroes howling and their chains

entangled with the flames:

“That the burning blacks could not be reached,

that the Crew abandoned ship,

leaving their shrieking negresses behind,

that the Captain perished drunken with the wenches:

“Further Deponent sayeth not.”

Pilot Oh Pilot Me

16 Transcript of the reinterpretation of Robert Hayden’s poem as performed by the Black Storytellers of San Diego. Transcription by Wanda G. Addison.

17 “Middle Passage” as performed by the Black Storytellers of San Diego. Ellipsis indicates places words could not be clearly understood.

Lingering Spirit of the dead, rise up and possess your bird of passage.

Those stolen Africans … from the wounds of the ships and claim your story.

Spirit of the dead, rise up

Lingering Spirit of the dead, rise up and possess your vessels.

Voyages through death to life upon these shores.

The middle passage

Sails flashing to the wind like weapons

Sharks following the moans, the fever, and the dying

Blacks rebellious. Crew uneasy.

Their moaning is prayer for death, ours and their own

Some tried to starve themselves.

Lost three this morning leaped with crazy laughter to the waiting sharks,

sang as they went under.

{singing of an African song}

Standing to America, bringing black gold, black ivory, black seed.

I’ve heard of slavers drifting, drifting

Playthings of wind and storm and chance, their crews gone blind, the jungle

hatred crawling up on deck.

That there was hardly room ’tween-decks for half the sweltering cattle

stowed spoon-fashion there; that some went mad of thirst and tore their

flesh and sucked the blood

Where the living and the dead, the horribly dying, lie interlocked, lie foul

with blood and excrement.

Voyage through death to life upon these shores

Shout to the … of history

{In unison} The dark ships move. The dark ships move.

Weave toward a new worlds …

Those Africans shackled in leg irons, lynched, tied, bound, whipped, raped,

bred, and …

You Africans Spirits: Ashanti, Wolof, Bantu, … Mende, …

Step out and claim your stories!

Brought here on slave ships were bright, ironical names:, Jesús, Esperanza,

Estrella, Mercy, Desire, … Butterfly, the Independence, Spitfire, Excellence,

Huntress, the Wonderer, Orion, Wildfire …

{In unison} Spirit of the Dead, rise up!

18 Hayden’s poem recounts the cruelty of the slave trade and slave traders and a rebellion aboard one of the Spanish ships, La Amistad. The poem’s revision performed by BSSD (page 7) infused elements of direct address into the account of La Amistad’s voyage. The storytellers began with a twice-spoken refrain, “Spirit of the dead, rise up,” which was also repeated at the end. Calling forth the ancestors, invoking their memory and experiences imbued the performance with solemnity and honour evoked by the history in the poem, one of Africans contained like canned sardines in the bowels of ships, dying in the shackles, the living and the dead conjoined, or jumping to their deaths in the waters.

19 It was into this poem the storytellers stepped, bringing to life a memory not lived by any audience member, but one interwoven within the cultural reality of America and African Americans. “Spirit of the dead, rise up” anchored the section. The beginning set the stage of what was to come. The BSSD were at once calling upon the known and unknown ancestors to enter and be remembered and upon the living to remember their ancestors and the legacy of their actions. Near the end of this performance, one teller said, “Step out and claim your stories!” Clearly in this context, the teller was speaking to the aforementioned spirit. However, she had likewise embedded in this call to claim cultural stories an insistence for the audience not to forget, not to have someone else’s version be the only one known. In essence, they were to step out and claim their stories as well. Speaking of female forebears, Elaine Lawless notes, “We tell our stories backward” (2011: 142). This notion applies well to ancestors as a whole. It is from looking through the lens of where we have come and voicing those stories of our individual and collective histories that we begin to fashion the present and future, and unite more intimately with the legacy.

20 Hayden’s poem is noticeably absent any voices of the enslaved men, women, and children carried in the deplorable, inhumane conditions of the ships. In this absence, Hayden captures the history of silencing and invisibility inflicted upon Black Americans. Countering the implicit history embodied in the poem, the storytellers performed the choral reading in multiple voices, ensuring that each of the seven performers on the stage spoke and represented a previously silenced voice. The slave trader’s voice is primary in the poem, and it overlays his reality onto the experiences of others. So, the call to action in “claim your stories” reflected the verbal resolve embedded in this Black History Month program. Through this event, Black Americans claim their histories, their ancestral experiences, and the stories of their respective lives connecting the dots on the landscapes of their legacies. Black Americans telling the stories of their lives to those who come after them—so that the youth can become anchored in their present while seeing the expanse of time upon which they exist—is the second call to action.

21 Ending the first section with “Spirit of the Dead, rise up” segued to the second section, a story about people who could fly. This is a story of African people who are noble in their country but diminished by slavery though still possessing their greatness. The storytellers began:

They say that long ago in Africa, some people knew magic.

And they would walk up on the air and climb up on a gate.

And they flew like black birds over the fields....

22 These great people who could fly in their homeland could not take their wings on the slave ships, so they cast them off. However, all was not lost:

They kept their secret magic in the land of slavery.

They looked the same as the other people from Africa who had been coming over,

who had dark skin

Say you couldn’t tell anymore one who

could not fly from one who could....

They say that the children of the ones who

could not fly told their children the story

of those who could fly.

And now we—each storyteller points to self—have told it to you—each storyteller points toward the audience.(Fig. 5)

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5

23 The opening phrase “they say” framed the section and marks it as a story of importance. “They say” offered the audience the beginning of a tale from long ago but concluded with modern-day impact on the cultural and personal realities of each audience member. The pronoun “they” shifted from the storytelling marker in lines 1 and 2 to referent for the people themselves in lines 3-7. In the context of the libation and the first choral reading, introduction of the collective “they” in line 3 subsumed the audience in the shared experience and revisioned the alluded-to heritage as inclusive of African Americans as a whole. In lines 1-4 a counter-narrative of greatness was reinforced. They, the ancestors subjected to slavery, possessed something within that did not limit them to what others might say or do. Although the ancestors shed their wings because of slavery, their power remained. While they were outwardly similar to others, they were inwardly greater than their current conditions and this was never forgotten.

24 Elements of a return to the story frame marker threaded throughout the narrative can be seen in lines 5 (“Say the people”) and 8 (“Say you couldn’t tell”) and anchored at the end in line 9 with “They say.” This move allows the mixture of recounted narrative experience to become intermingled with imagined possibilities for the audience. After those who lost their wings “joined hands and would sing as they rose in the air. They flew in a flock that was black against the heavenly blue.” Although they were no longer with those who could not fly, the legacy could not be allowed to be forgotten. Therefore, each one must be compelled to continue sharing the narrative of the people who could fly and, by extension, the heritage of greatness and power that travels along the spectrum. The message from Moyenda’s libation is reinforced in line 10: each person must listen to the ancestors and share their stories, keeping cultural legacies and those along the continuum united.

Conclusion

25 I began thinking about the role of Black History Month programs before my ethnographic work with the Black Storytellers of San Diego, Inc. What role, I have wondered, do Black History Month programs play in the lives of the audience and performers after the program has ended? I believe the beginnings of the answers have been presented in this paper. The weight of performance as cultural expression is evident as a grounding force within Black American diaspora communities seeking connection with centuries-long legacies threatened with being forgotten. In searching for home, Ruth Behar poses the question of a multicultural America with a mixed race president. She writes, “Is Obama ‘black enough’ or ‘the new black’?” (2009: 263). Black History Month programs, in part, bridge apparent or constructed distance between problematic concepts like “being black enough” with what remains ahead. Whether or not it involves conversations of new or post-blackness, the idea that black identity is no longer constrained by the burden of identicalness across the Black American Diaspora encompasses multiplicities of blackness. Black History Month programs perpetually make similar claims on “home” through creating event space as “solidarity builder” fostering connection with each person in the audience and with heritage and ancestors. These programs call on Americans to remember the foundation, the history, and the legacy which binds all Americans while countering external narratives of home and Black American identity through voicing ancestral stories that situate Black American nation-home squarely within American shores.