Research Reports

The Daily Grind: The Rotary Quern and Nova Scotia’s Scots

Abstract

Although the history of the quern (hand mill) in Scotland has attracted extensive academic attention, the cultural diffusion of this domestic tool to North America is little known. This preliminary investigation into quern use among Nova Scotia’s Scottish immigrants reveals that querns, despite their cumbersome size and weight, were transported to the colony and were regarded as tangible and portable symbols of a distinctive way of life. The quern’s utility and intrinsic value were augmented by its link to story and song, as well as cultural self-reliance, male physical strength, and female participation in rural food production. This study points to the need for a quern inventory in Nova Scotia to establish a more comprehensive profile of the distribution, design, and lithology of querns used by the early Scottish settlers..

Résumé

Bien que l’histoire du moulin à bras en Écosse ait attiré l’attention de nombreux chercheurs, la diffusion culturelle de cet outil domestique en Amérique du Nord est assez peu connue. Cette étude préliminaire de l’usage du moulin à bras chez les immigrants écossais de la Nouvelle-Écosse révèle qu’en dépit de leurs dimensions encombrantes et de leur poids, les moulins à bras ont été transportés dans la colonie et étaient considérés comme les symboles portatifs et concrets d’un mode de vie particulier. La valeur intrinsèque et la valeur d’usage du moulin à bras étaient d’autant plus importantes qu’elles étaient liées à l’histoire et à la chanson, ainsi qu’à l’autonomie culturelle, la force physique des hommes et la participation des femmes à la production de la nourriture en milieu rural. Cette étude souligne le besoin d’un inventaire des moulins à bras utilisés par les premiers colons écossais en Nouvelle-Écosse, afin d’établir un profil plus exhaustif de leur répartition, de leurs modèles et de leur lithologie.

1 Despite its rustic appearance and simplicity of design, the quern, otherwise known as the hand mill, is no ordinary object. 1 Consisting of a pair of stones designed to grind and mill cereals by hand, it has been described as a “special” artifact, which connotes subsistence and sustenance in a manner that few other artifacts can approximate (Watts 2014). Since E. Cecil Curwen pronounced in 1937 that “a gap in our knowledge” about the quern “is crying out to be filled,” there has been a substantial outpouring of research, both archaeological and ethnographic, into the history of quern use in Scotland and England (1937: 133). Scholars, such as Alexander Fenton, and, more recently, Euan MacKie, Fraser Hunter, Dawn McLaren, and Susan Watts, have successfully spotlighted the importance of the seemingly humble quern, whose origins are rooted in prehistoric times and whose cultural diffusion is worldwide. Their research has demonstrated that as human history progressed through the Neolithic, Bronze and Iron Ages, it witnessed the shift from the mortar and pestle to the saddle quern and to the more complex rotary quern, which was nothing short of a major technological revolution with wide-reaching functional and symbolic dimensions.

2 This scholarly scrutiny notwithstanding, the history of the quern in North America, especially among the immigrant Scots, is an unexplored and underappreciated field (Fig. 1). Far too often, one is left with the impression that the Scots came to the colonies with little more than the clothes on their backs. Physical and documentary evidence, however, presents a very different picture. Moreover, although historians have long assumed that the quern’s substantial dimensions precluded portability, size and weight were not necessarily decisive factors in determining what personal possessions did or did not accompany the Scots overseas. The “Ox Mackays,” for example, travelled from Sutherland to Central Canada in 1831 with an axle and two wheels in tow (Mackay 2014). Immigration clearly favoured the physically robust, as seen in the story of Dougal McPhee, who came to Eastern Nova Scotia with his wife and children during the early 19th century. According to family tradition, McPhee tramped along South River, in Antigonish County, wading part of the way, while carrying a quern and spinning wheel on his back, and hauling a chest, which was secured in a sling fashioned from his plaid (Hart ca. 1935: 2, 7).

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 13 Our limited understanding of quern use among Nova Scotia’s immigrant Scots is due in part to the fact that the material aspects of the Scottish emigration experience are often overlooked.2 Even less is known about the rationale behind the selection of those possessions that immigrants chose to accompany them into exile. In family stories, one finds specific descriptions of these objects, which were much more than just fragments of disrupted personal and cultural lives. They constituted parts of a whole as portable tokens of a distinctive way of life. Family narratives often refer to Gaelic bibles, and kilts and plaids, “carefully kept and mended,” as making the transatlantic trip (MacKay 1980: 172). Many chosen objects had an obvious utilitarian value. For example, Joseph MacNeil, a Barra blacksmith, decided to bring a cast iron Dutch oven to Christmas Island in 1817, while a family of MacNeils at Washabuck Centre, Cape Breton, crossed the Atlantic with a large, three-legged pot, which had seen service in a field kitchen at the Battle of Waterloo (Collections Inventory; MacLean 1940: 51). Local inhabitants affectionately dubbed the pot “The Waterloo Veteran.” Some decisions stemmed from sentiment rather than practicality. Lucy MacNeil, daughter of Donald Piper MacNeil, and wife of Murdock MacKenzie, elected to immigrate to Washabuck, Cape Breton, with the white dress she had worn on her wedding day in Barra, Scotland, ca. 1817 (Collections Inventory).

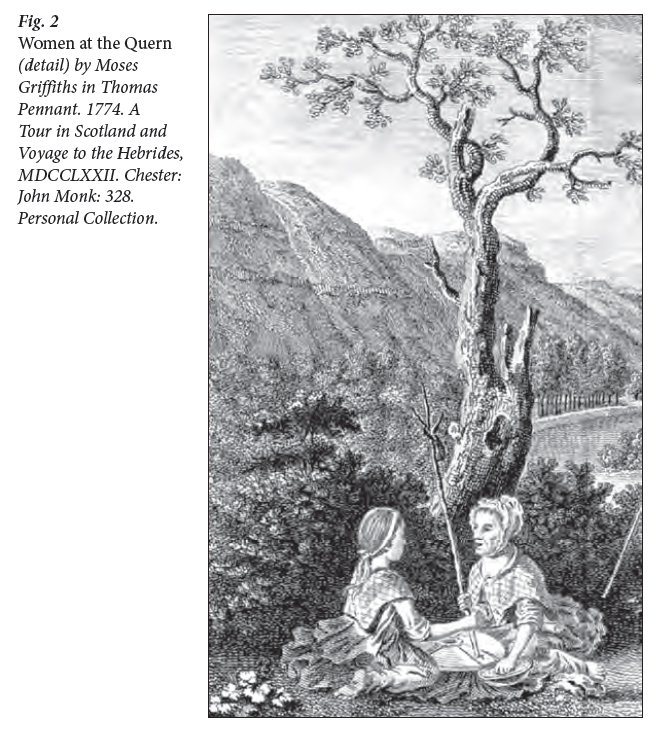

4 One of the most noteworthy physical artifacts to make the trip from Scotland to Nova Scotia was the rotary quern. This phenomenon reflected in part the hand mill’s “late survival” in the Highlands and Islands of Scotland, long after its obsolescence in other parts of Great Britain (Euan MacKie, personal communication, July 13, 2015). The persistence of quern technology among the Scots, which dated back to Iron Age Scotland, frequently elicited the curiosity and commentary of outsiders such as Thomas Pennant, who visited the Highlands and Hebrides in the 1760s. As shown in Fig. 2, he encountered in Talisker, Skye, two women kneeling on the ground beside a quern, which they rotated with the aid of a long pole handle wedged into a socket in the upper stone. Regrettably, such detailed documentation does not exist for late 18th- and early 19th-century Nova Scotia, and one cannot state with any precision how many rotary querns were used in the colony at that time. Still, evidence exists, such as family histories which definitively corroborate the migration of Scottish querns to Nova Scotia. For example, George Taylor sailed from Scotland to Nova Scotia with a two-handled granite quern (each stone weighing 40 kg [90 lbs], upper stone 50 cm [20 in] in diameter, lower stone 56 cm [22 in] in diameter); he became the first settler at Taylor’s Settlement in the Musquodoboit Valley (Piers 1928). One of the MacKenzie families of Christmas Island, Cape Breton, transported a hand mill from Barra in the early 1820s (Collections Inventory). A quern also figured among the personal effects of Mrs. Red Donald McNeil, who travelled with her quern from Barra to Grand Narrows, Cape Breton, via Pictou, in 1804 (Dunn 1991: 55). One of Anne MacKay MacKinnon’s descendants recalls that she received as part of her marriage portion a quern, which she brought in the 1820s from the Isle of Muck to Rear Baddeck, Cape Breton, along with a chest half-full with oatmeal (Barry Fraser, personal communication, June 21, 2015). Likewise, the pioneer ancestor of one of Cape Breton’s MacRae families brought three hand mills to Nova Scotia and gave a set to each of his sons.3

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 25 In researching the history of quern use in Nova Scotia, one is struck by the fact that querns sometimes developed remarkable life stories over time. In this way, they possessed a numinosity, endowing them with emotional significance as personal and communal markers (Maines and Glynn 1993: 10). It is recorded in local lore that in 1816 in Pictou County, a year after a notorious plague of mice laid waste to the settlers’ fields, there was a “bountiful crop” for which all were truly grateful. On the Reid Farm at Black Point, Little Harbour, the harvesters gathered the barley, while Mary Reid followed behind binding the sheaves. She took the first sheaf, threshed, winnowed, and dried it, then ground it with the family quern. It is stated, “that evening the reapers sat down to a meal of barley cakes, the grain of which had been growing in the field in the morning” (Anonymous n.d.). In Antigonish, one Highlander boasted ownership of a quern that was “greatly” valued because of its alleged distinction of having “once ground the corn [grain] that made a hasty bannock for Bonnie Prince Charlie” (S. A. 1890: 1). The quern of Mrs. Red Donald McNeil of Grand Narrows, Cape Breton, was also invested with elite connotations. Her quern enjoyed local celebrity for having ground the flour for the bread which was consumed, along with vast quantities of milk, by Bishop Plessis and his two French priest companions, who visited Christmas Island parish in 1815 (MacKenzie 1984 [1926]: 150).

6 One cannot state with precision when the Scottish settlers first brought their querns to Nova Scotia.4 It is alleged that, before the arrival of the Scots in Antigonish County, the region’s first wheat crop—“little more than a handful” that grew sparsely among the stumps—was dried in a pot and ground in a coffee mill (Rankin 1929: 9). Even among the early Highlanders, there was a limited number of querns. According to Father D. J. Rankin, writing in the late 1920s, “it was customary for people to flock every evening to the nearest house where a hand mill was kept to get a peck or so of wheat ground to serve the following day”(41). Owing to the shortage of querns, some of the early Scottish settlers made do with boiling their grain, but in time, “there was one [a quern] in every house” (MacDonald 1975 [1875]: 11). A similar situation prevailed in Pictou County, where, according to the Rev. James MacGregor, Pictou County’s first settled Gaelic-speaking Presbyterian minister, every family possessed a quern “for its own use” (Patterson 1859, 126). In these published sources, there is substantial disagreement over how frequently querns were used in rural Scottish immigrant households. The Rev. MacGregor claimed that the inefficiency of this device contributed to its unpopularity and that consequently meals were frequently devoid of bread (127). In striking contrast to MacGregor’s recollections, William Cameron, who wrote in the early 1900s under the pen name Drummer on Foot, stated that large families in Antigonish County used querns regularly, employing them most commonly at nighttime (MacFarlene and MacLean 1999: 89).

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 37 Typically, in the Scottish Highlands, it was the woman’s job to keep the household in meal. In short, hand grinding was women’s work, but quern use among Nova Scotia’s Scottish immigrants was not so sharply gendered. According to the Rev. George Patterson, an early Pictou County historian, querns in Pictou County were usually operated by a man (singly), while either a woman or a man was tasked with pouring the dried grain into the feed pipe (“the eye”) of the top stone to be ground (1859, 126-27). Antigonish County’s Father Ronald MacGillivray, known locally as “Sagart Arisaig,” depicted a more gender-based division of labour, which correlated more closely with grinding practices in Scotland. Basing his observations on the reminiscences of John McNeil, the son of one of the pioneers of “The Cove” in Antigonish County, MacGillivray wrote,

8 The technique for transforming barley, wheat, and oats into a consumable product was not a simple task. This process, however laborious, possessed a scientific logic, based on the Scottish pioneer’s intimate understanding of those weather conditions best suited for ripening, drying, and winnowing.5 This preparatory work paved the way for the grinding, at which stage the quern was brought into service. By all accounts, operating this mechanism was physically arduous, but the Rev. MacGregor noted that the top stone could rotate with great rapidity depending on the user’s strength.

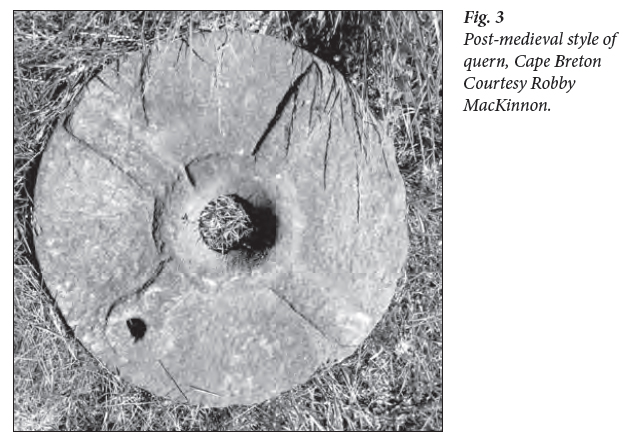

9 Based on the twenty querns I have identified thus far in my research (not including those consulted in Prince Edward Island and Ontario), the Scottish settlers in Nova Scotia used a variety of querns, ranging in size from 23 cm (9 in) in diameter to approximately 56 cm (22 in) in diameter. Although the querns in this limited dataset are disc-shaped, slightly domed in profile and favour the single-socket vertical handle, there is no uniform style of quern. They are fashioned from multiple stone types, such as sandstone, gabbro, andesite, and granite. (Brendan Murphy, personal communication, June 30, 2015). Most of the quern samples lack the original rynd, a wooden or metal bar with a socket that was wedged into a centrally positioned recess on the underside of the top stone. This feature, in combination with a spindle of wood or iron contained within a plug in the lower stone, enabled the stones to be aligned and adjusted to reduce friction and excessive production of grit. Two of the querns stand out as noteworthy. Although decorative elements are rare in this sampling, an 46 cm (18 in) quern (Fig. 3) from the Sydney area, Cape Breton, features a raised collar around the feeder pipe and socket handle, as well as four radial raised wedges, which simulate a cross. Apart from the absence of multiple socket handles, this post-medieval quern type bears a striking resemblance to the device depicted in Fig. 2. The second 23 cm (9 in) quern, equipped with a lateral handle slot and a raised stone grinding surface on which to pivot, can be classified as a pot quern, which was popularized during the Middle Ages and so named because the smaller upper stone sits within a larger stone with raised sides (Fig. 4). The smallness of its dimensions and the narrow outlet hole on the side of the lower stone point to the distinct possibility that it is a snuff quern designed to grind dried tobacco—a logical conclusion given the documented popularity of snuff among Highland immigrants, especially women.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4 Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 510 Most of the querns in this sampling were operated by a wooden peg-like handle, but written accounts suggest that, with the larger querns, early Scottish immigrants used a longer wooden pole, the lower end inserted into the top stone and the upper end fixed in a cross piece of wood, fastened to the exposed upper beams of the house. None of the sources used for this project indicates that querns in Eastern Nova Scotia and Cape Breton functioned out of doors. Instead, several accounts state that many of the later adjustable querns were mounted on a specially constructed wooden frame (which, by means of a cord and a lightening rod mechanism, permitted regulation for coarse- and fine-ground flours), whereas smaller quern variants were placed on the table, with a sheet or skin to catch the overflow of ground meal which spilled out the sides of the hand-mill (MacLean 1940: 54).

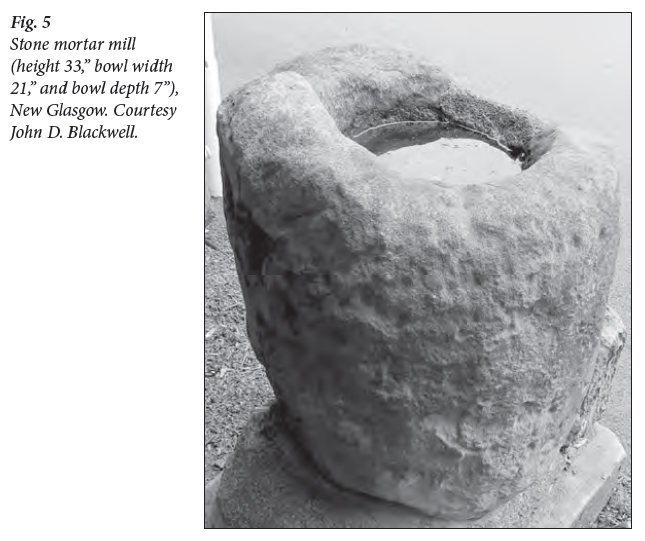

11 One of the most intriguing references to quern use in Nova Scotia describes how the Skye-born Alex MacDonald of Glasgow Brook, Cape Breton, improvised a mechanized version of the quern, which functioned like a small horizontal water wheel. It is recorded that MacDonald “set up his hand-mill on a little brook near his house” so that “he could have his grain ground while he slept” (MacDonald 1933: 67). His source of inspiration was undoubtedly the clappan mill (sometimes called a Norse mill), a once-common type of water mill found not only in the Shetland Isles, but also Orkney and Lewis. An exceptional example of an early mortar mill has survived and can be found in Pictou County (Fig. 5). Typically operated in combination with a wooden mallet or a smaller stone, along the lines of a mortar and pestle, this mortar mill, with its hollowed-out centre, operated as the first mill in Little Harbour, Pictou County, from 1780 to 1830 (M. Cullen et. al. 1984: 17-18). Termed a “knockin’ stane” in Scotland, this milling device was best suited to processing barley, especially removing husks or bran, whereas the quern was decidedly more proficient for grinding oats and wheat.

12 One can only speculate about what thoughts occupied the Scottish immigrant housewife, as she leaned into her quern, grasping the wooden handle, turning the top stone clockwise, occasionally stopping to lick some flour off the stones. Sadly, extant sources, both textual and oral, do not permit us to reconstruct with certainty the degree to which Scottish immigrant women endowed their querns with a prioritized meaning. Certainly, there is evidence verifying that other domestic items, especially those used on a daily basis, formed a special relationship with their users. For example, according to an early 20th-century Cape Breton amateur historian, Murdoch D. Morrison, the spinning wheel ranked high in the affections of the Scottish female settler: “With what pride she spoke of the age and endurance of her wheel, how little oil it required, and how seldom she broke the connecting rod” (1931: 11-12.). For one Scottish emigrant woman in Pictou County, few pioneering hardships tested her fortitude as severely as the destruction of two iron pots that she had brought from Scotland. Left filled with water, the pots had cracked in the freezing temperatures. She later claimed that her grief over the loss of these objects equalled the heartache caused by the death of her child (Patterson 1877: 96ff).

13 Containing pithy truths about the human condition, Gaelic sayings provide important insights into the quern’s singular place in the lives of the Highland Scots. The experience of querning left an imprint on Gaelic folk wisdom, spawning such riddles as “an old woman in the corner, spokes through her two eyes, and she is grumbling” and aphorisms such as “A quern is the better for being picked but not broken,” “Coarse meal is better than to be without grinding,” and “A growing boy eats like a quern grinds” (Watts 2014: 46; Mac-Talla 1895-1896: 1; Mac-Talla 1901-1902: 99, 339; Mac-Talla 1895-1896: 7). Charles Dunn actually cited this latter proverb in his 1959 seminal article, “Gaelic Proverbs in Nova Scotia” (1959: 33). The quern’s history as a much-persecuted object also helps explain its emotional weight in terms of practical and symbolic meanings. The Scots in the Highlands used querns to do their own milling, most notably to avoid the orbitant charges levied at the landlord’s mill (Hornsby 1990: 52). In order to prevent the tenants from milling their own grain and to enforce the estate mill’s monopoly, with the landlord and miller acting as “technology gatekeepers,” threats of fines and even the confiscation of stones were often held over the heads of quern users (Barrels, 2012: 51, 55). Although the enforcement of such practices appears to have been partial and regional, Angus MacLellan’s The Furrow Behind Me contains the unforgettable image of Loch nam Braithntean (“loch of the querns”) in South Uist, which became a watery grave for banished local querns (1997: 7). Under such circumstances, querns most likely possessed a psychological relevance for many Scottish immigrants, as fellow travellers on an historical journey marked by repression, defiance of authority, and assertion of self-reliance.6

14 The role of the quern has long been interwoven with story and song.7 Although a well-known subset of Gaelic work songs, quern songs do not appear to have survived as part of the performance repertoire of Nova Scotia’s Gaels. There are several possible explanations for this loss, the most obvious being the decline in quern use. In the early 1890s, Henry Whyte, using the pen name Fionn, sounded a note of alarm: “The quern songs are fast passing away,” he wrote, “and it would be well that such as have the opportunity should collect any they may hear throughout the Highlands” (Fionn 1893: 626). However, it is possible that the fate of querning songs in Cape Breton was not solely dependent on the disappearance of the quern. Matthew D. McGuire, author of Music in Nova Scotia: The Oral Tradition, states that the grinding of grain in Nova Scotia was sometimes performed during milling frolics, with a couple off to one side of the room operating the quern (1998: 35). Consequently, milling songs doubled as querning songs, and may have inadvertently pre-empted them, especially as the presence of men had an increasingly significant impact on the milling repertoire. The increasing prominence of the grist mill, sometimes dotting the 19th-century landscape of Nova Scotia every three to four miles, also spelled the decline of this variant of work song.

15 Although the quern was eclipsed in song, it retained its importance in the stories of Scottish tradition bearers in Nova Scotia. It figured in tales celebrating male physical strength, such as the much-storied exploits of Big Allan McDonald of Keppoch, a former champion stone thrower, who lugged a huge grinding stone on his back from Antigonish to Keppoch Mountain, an ascent which Father McGillivray described as “steeper than the winding stairs that lead to the top of St. Peter’s in Rome” (MacLean 1976: 82; Stanley-Blackwell and MacDonald 2010: 253-66).

16 The quern also featured in narratives related to Gaelic hospitality, such as “The Traveler and the Bannock,” which was part of Joe Neil MacNeil’s abundant storehouse of remembered tales (2008/2009: 6-7). The quern took centre stage in William Cameron’s account of an Antigonish County romance in the 1860s that blossomed between a Keppoch Mountain youth with a team of oxen and a young girl with a quern and a wash tub of oats.8 “By the time the boy had the oxen watered and fed, the speckled fish and oatmeal cakes were ready to be served for dinner” (MacLean 1963: 12-13). A quern was also pivotal to the story of Judge John G. Marshall’s visit to the home of Donald Gillis in Ben Eoin, Cape Breton, during the early 19th century. The Gillises deemed their meal of codfish and potatoes adequate fare for themselves and Marshall’s companion, the mail carrier, Donald MacLean, but insisted on preparing something more elaborate for the judge. Staving off hunger pangs, he waited while his hosts dried, ground, and sieved some home-grown wheat, which was baked in a pot-shaped oven in the open fireplace, their labours resulting in a repast of bread, butter and tea for the Judge (MacKinnon 1918: 52-53). Instead of depicting the quern as an inferior domestic appliance and querning as a lowly chore, these stories underscored its centrality in the hosting of guests and visitors.

17 It is difficult to pinpoint when querns were finally abandoned in the Scottish immigrant communities of Nova Scotia. According to Arthur Mitchell’s The Past in the Present, “thousands” of querns were still in existence in Shetland, Orkney, the Hebrides, and in the west-coast parishes of Sutherland, Ross, and Inverness in the late 1870s (1881: 51). It is doubtful that the figure would have been this high for Nova Scotia (Stephens 1973: 2). The establishment of grist mills in Eastern Nova Scotia and Cape Breton undoubtedly played a role in the quern’s demise. Initially, insufficient capital in Cape Breton hindered investment in grist mills. However, by 1851, there were seventy-five grist mills in Cape Breton, one for every eighty farmers; grinding grain at this stage was primarily for domestic production (Hornsby 1992: 81). The grist mill’s impact on the quern’s declining household importance was by no means sudden or evenly distributed in its impact. Historical accounts suggest that during the winter freeze-ups and the summertime droughts, when the waterwheels came to a halt, the quern remained a familiar default.

18 The proliferation of grist mills not only contributed to the quern’s obsolescence as a tool for food processing and as part of a social network, it also eroded women’s role in this important facet of food preparation. As mill roads became vital systems of communication throughout Nova Scotia, the grist mill and the miller became the focal point of the economic and social life of communities. It was a decidedly male space, where men congregated to swap the latest news, fiddlers performed, and young boys hovered, hoping to fill their pockets with stolen grain (Maynard 1994: 93).

19 In the early 19th century, there were already signs pointing to the fact that the quern was starting to loosen its hold as a domestic appliance among Nova Scotia’s immigrant Scots. By this time, wheat production and grist mills were regarded as the benchmarks of progress and prosperity. It is telling that the eminently practical Highland settlers of Earltown, situated near the Antigonish-Pictou County border, many of whom came from Sutherlandshire, made arrangements in the early 1820s to retain the services of a miller even before sending out the call for a settled minister (Patterson 1877: 278).

20 As the ideology of modernized agriculture fanned out across Nova Scotia in the form of agricultural societies, handsome government bounties for mills, increased wheat production, and the touted benefits of “fine” flour, oatmeal of “proper granulation,” and “well manufactured” barley, the quern fell increasingly into disrepute among champions of agricultural reform as a marker of poverty and backwardness in the same manner as homespun (Martell 1940: 45).

21 Negative perceptions of the quern as a barbarous artifact were undoubtedly rooted in the stereotypical categorization of Highlanders as subsistence-oriented and lacking the industry and progressiveness of their English and Lowland Scottish neighbours (MacNeil 1986: 39-56). It sounded almost like bragging when the Pictou County historian, the Rev. George Patterson, writing in the late 1850s, claimed that he had never set eyes on a hand mill in his life (1859: 127ff). The Rev. James MacGregor, an early advocate of scientific agriculture in Pictou County, reviled the quern as a rude contrivance and did not spare his criticism. He recounted that his arrival at a parishioner’s home ushered a frenzy of hand milling, which drowned out the conversation, and virtually excluded the operator from participating fully in any dialogue. He concluded that these circumstances contributed to the inefficiency of his rounds, slowing him down to visiting one household in the time that he had hoped to accomplish two (Patterson 1859: 127). MacGregor’s disdain for the quern was shared by Father Ronald MacGillivray, a collector of Gaelic poetry and local history, who dismissed sentimental attachment to the device and refused to “genuflect before this sorry production of industrial mechanism” (S. A. 1890: 1).

22 Although storytellers stressed the swiftness with which this household convenience transformed grain from the nearby field into meal for bannock or porridge without miller’s fees or backpacking a great distance to a grist mill, late-19th-century newspapers pronounced mechanized milling as a superior form of production and time management. One Pictou newspaper declared: “Mr. Sandy Morrison (a resident of Lyon’s Brook) made somewhat of a record in transforming wheat into bread. He cut the grain on Saturday last, brought it into the Atlantic Milling Co., on Monday and baked bread with the flour on Tuesday” (Scrapbook 1916).

23 In contrast to the exponents of modernization, there were stalwarts in Nova Scotia who disputed the quern’s increasingly maligned reputation for drudgery, uselessness, and waste. They championed its efficiency for home consumption, and the freshness and nutritiousness of its product. J. L. MacDougall of Strathlorne, Cape Breton, author of History of Inverness County, Nova Scotia, wrote in 1922: “The flour or meal thus ground was coarse food, but wholesome. There were giants in those days; and they were needed to remove the tyranny of the tall timbers” (1922: 5). Alex D. MacLean, a local Washabuck historian, said much the same thing, claiming: “The meal turned out in this way was much coarser than the flour to which we are accustomed today. Those who have used it are unanimous in saying that it was far superior, and more nourishing than the present day flour” (1940: 54). For Jonathan MacKinnon, editor of the Gaelic periodical, Mac-Talla, arguments in defence of querns had more to do with cultural identity than healthy nutrition. Although querns are scantly referenced in his newspaper, he published an article titled, “The Quern-Stone,” from the Highland News, in which the author railed:

24 Ironically, some of the most eloquent defenders of the quern were outsiders, who regarded this device as a quaint example of pre-industrial primitivism. American journalist, Charles Farnham, hooked the readers of his Harper’s New Monthly Magazine article, “Cape Breton Folk,” with the opening line:

Display large image of Figure 6

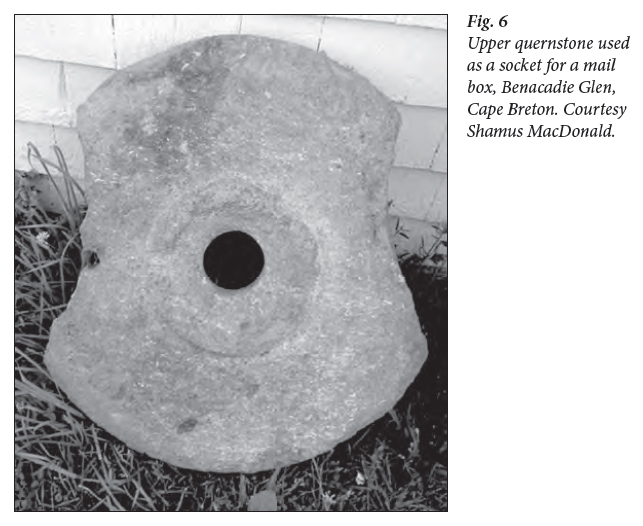

Display large image of Figure 625 Given their ubiquity in the early Scottish settlements of Nova Scotia, one is left wondering what happened to all the querns which were once so central to the lives of Nova Scotia’s Highland immigrants. According to early Washabuck historian, Alex D. MacLean, querns were “laid aside,” unthinkingly cast into a limbo of rubbish (1940: 54). However, the reality is much more complicated than that. Susan Watts’s theories about the “structured deposition” (i.e., purposeful placement) of querns in prehistoric south-western England provide an interesting interpretive tool. There was a spectrum of responses to the quern’s obsolescence in Nova Scotia, which epitomizes what Watts labels as “different levels of meaning and intent” (2014: 139). Although querns were displaced as domestic implements, they were not discarded randomly but found reuse in secondary contexts. Given their physical properties, not surprisingly, querns in Nova Scotia were often re-purposed as threshold stones, foundation stones, and paving stones for walkways. Nova Scotian querns also took on second lives as the bases for mail-box posts and as garden planters (Fig. 6). The Little Harbour mortar mill was reinvented as a bird bath, in 1935, to adorn the front lawn of the massive residence of New Glasgow industrial magnate and politician, Thomas Cantley (Fig. 5). The stone mill was fitted with a stone plaque, bearing Cantley’s thistle-themed coat of arms and motto, as well as an inscription. In this way, the nouveau-riche Cantley laid claim to the relic while attempting to secure the sanction of antiquity. For some families, the quern became a vector of familial and social memory across space and time. In at least one documented instance, this object was dutifully transported to family reunions. A quern at William’s Point, near Antigonish, was stored in a shed for generations, where it served as “a show and tell piece” for members of the Grant family (NovaMuse, accessed September 26, 2015, http://www.novamuse.ca/index.php/Detail/objects/86837 ).

26 According to Port Hood local historian, John Gillies, a set of quern stones used to lie on the banks of a brook at the foot of Glenora Falls, the site of an early grist mill (personal communication, June 19, 2015). The proximity of two related examples of milling equipment seems more than just happenstance. In fact, it seems a fitting burial site, given the congruence of location and associated artifacts. Nova Scotian querns were also deposited in local museums such as the Greenhill Pioneer Museum of Pictou County, which opened as a tourist attraction in 1933 (Anonymous ca. 1947). Among its display of pioneer articles was a quern, purchased with a financial donation from Ramsay MacDonald, former prime minister of Great Britain. There, the quern served as a curiosity of bygone folkways, a gauge for measuring the cultural advancement of the Scottish pioneers: “to give some idea of the grim, hard life of the early settlers in that age when Nova Scotia made such wonderful strides in culture and industry” was how the tourist brochure read (Anonymous n.d.). In contrast, querns were also rehabilitated as highly-treasured relics and visible ancestral remembrances at the St. Ann’s Highland Folk Museum in Cape Breton in the late 1930s and at Dan Alex MacLeod’s private museum, aptly called Taigh an Iongantais (House of Wonder), in Stirling, Cape Breton, which he operated until his death, in 2000. In these latter settings, the quern was not a source of bemusement but a cause for cultural celebration.

27 It is clear that historians of the quern must cast their net more widely to include North America within their scholarly purview. The second phase of this study will invite a closer analysis of the querns themselves, noting variations in dimensions, shapes, stone types, presence or absence of decoration, dressing patterns on the grinding surfaces, and use-wear analysis. As demonstrated by the Yorkshire Querns Survey and the Moray Querners project, such data will open the door to a more comprehensive understanding of the use-life and use-context of Nova Scotia’s querns and a more informed discussion about the distribution and lithology of quern types in Eastern Nova Scotia and Cape Breton, and whether they were ever locally sourced and manufactured.9

28 The research conducted thus far demonstrates that the quern of the Nova Scotian Highland settler was much more than a simple, utilitarian object. Whether transported to or replicated in Nova Scotia, it embodied both functional and symbolic elements, representing the staff of life, the centrality of women to rural food preparation, technological transfer, the validation of folk memory, and a physical connection to the past. Despite a dichotomy of opinions about its value and eventual obsolescence as milling technology, the quern of the Nova Scotia Highland immigrant retained its mystique into the 20th century, straddling both the past and the present, in repurposed forms.

This research project was supported by the Strathmartine Trust, St. Andrews, Scotland. I would also like to thank the following people: Jane Arnold (Beaton Institute), Marcy Baker (St. FX University), Dr. Sandra Barr (Acadia University), Jennifer Black (Glengarry Pioneer Museum), John D. Blackwell (St. FX University), Lisa Bower (Nova Scotia Museum), Susan Cameron (St. FX University), A. J. Campbell, Professor Hugh Cheape (Sabhal Mòr Ostaig), Ruby Cousins, Michelle Davey (McCulloch House and Genealogy Centre), Barry Fraser, Byron Freese (Jones County History Society), Jocelyn Gillis (Antigonish Heritage Museum), John Gillies (Chestico Museum and Archives), Greg Hiscott (R. H. Porter Funeral Homes Ltd.), Dr. Guy Lalande (St. FX University), Dr. Margaret Mackay (University of Edinburgh), Teresa MacKenzie (McCulloch House Museum and Genealogy Centre), Dr. Euan MacKie (University of Glasgow), Robby MacKinnon (Robby MacKinnon Antiques), Pauline MacLean (Highland Village Museum), Kathleen MacLeod (North Highlands Museum), Anne Marie MacNeil (Beaton Institute), Shamus MacDonald, John Marshall (John Marshall Antiques), Glen Matheson, Dr. Brendan Murphy (St. FX University), Jacob O’Sullivan (Highland Folk Museum), Dr. Nicola Powell (Cotswold Archaeology), Effie Rankin, Karen Smith (Special Collections, Dalhousie University), and Dr. Susan Watts (Devon County Council Archaeology Service). Singled out for special acknowledgement are the Gaelic research skills of Kathleen Reddy (St. FX University) and the Gaelic translation expertise of Dr. Michael Linkletter (St. FX University).