Research Reports

Partible Objects: A Wayana Dance Costume Used as Shaman’s Device (Tropenmuseum inventory number 401-86a)

Summary

1 Drawing on the social-anthropological conceptualizations of “partible bodies” and “object biographies,” this article contextualizes the life history of a composite ethnographic object that was collected in 1903 among the Wayana indigenous people of the Upper Maroni River, Suriname, and of which one component (inventory number TM-401-86a) is currently curated in the Tropenmuseum, Amsterdam, the Netherlands. A critical reassessment of this object is made based on published reports, the collector’s unpublished notebooks and his personal diary, and almost twenty years of research by the author on the material culture and intangible heritage of the Wayana indigenous people (northern Brazil, southern Suriname, and French Guiana).

2 In the process of cataloguing, classifying, and labelling, some ethnographic objects may have received a description that is difficult for the museum visitor and the broader audience to understand, or which distorts the original meaning of the objects and how they came into being. This case study may also be used to reflect upon the role of the field collector, and how his or her actions or assumptions may inadvertently influence the process.

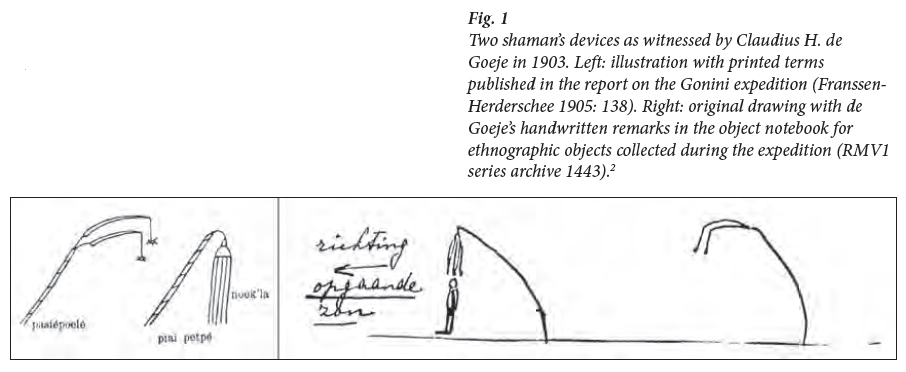

Introduction

Display large image of Figure 1

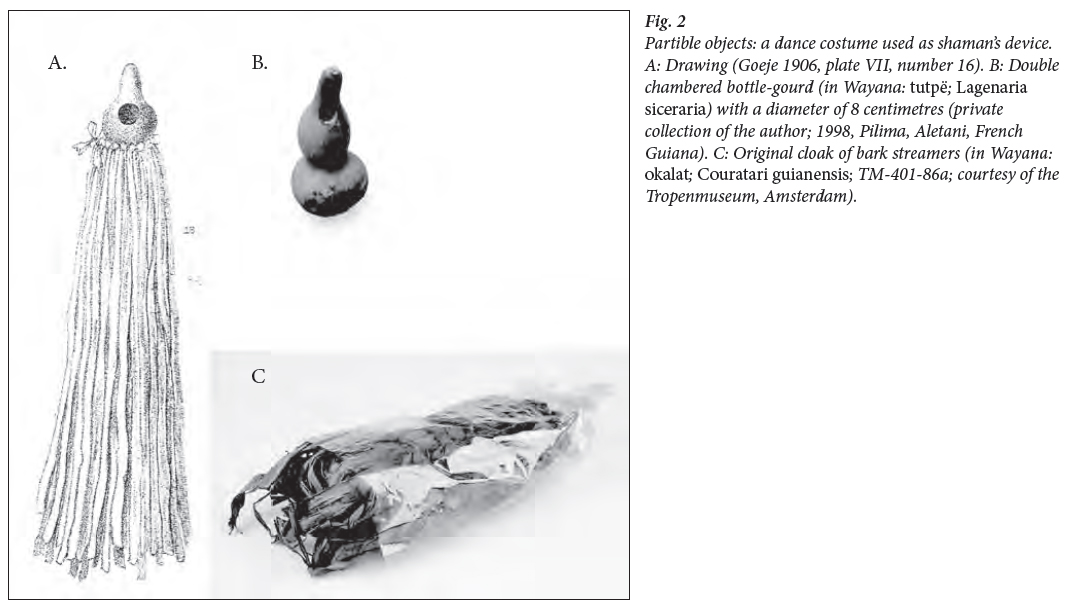

Display large image of Figure 13 Amazonianists in recent times demonstrate a renewed interest in the material culture of Amazonian indigenous peoples, though most of these studies situate the object or “thing” in the context of native Amazonian cosmologies and imaginaries (Santos-Granero 2009). This article (re)contextualizes the origin of an object (Tropenmuseum1 inventory number 401-86; hereafter TM-401-86) that was collected in 1903 among the Wayana indigenous people of the Upper Maroni River (Suriname), northern Amazonia. This object and its description is critically reassessed based on the unique primary data set consisting of (a) (part of) the artifact (TM-401-86a), (b) the published report on the Gonini expedition (Fransschen-Herderschee 1905:137-138), (c) the description and a drawing in Bijdrage tot de Ethnographie der Surinaamsche Indianen (de Goeje 1906: 26, plate VII, number 16), (d) unpublished notebooks regarding the collected ethnographic objects (RMV series archive 1443, object #49 [the last entry]), (e) the unpublished diary of Claudius H. de Goeje (which is in the possession of his grandchildren), and (f) almost twenty years of research by the author on the material culture and intangible heritage of the Wayana indigenous people of the Upper Maroni Basin (French Guiana and Suriname) (Duin 2009, 2014).

4 This case study may be used to reflect upon other ethnographic objects that have been found difficult to describe, and which in the process of cataloguing, classifying, and labelling, have received a description that does not align with the object’s multifaceted meaning. The cultural biography—in the sense used by Chris Gosden and Yvonne Marshall (cf. Appadurai 1986; Hoskins 2006; Kopytoff 1986)—of the ethnographic object discussed in this article is complex and challenging.

5 The cultural biography of object 401-86 spans more than a century. Gosden and Marshall (1999) focused on the life histories of objects in a museum setting, and drew upon Igor Kopytoff’s Cultural Biography of Things published in Arjun Appadurai’s 1986 The Social Life of Things, wherein it is argued that social valuables accumulate histories of exchange through time, and thus gain value. In this article I do not address the accrued values and the resulting “agency” or produced effects of this object, but instead I focus on its “dividuality,” in the sense used by Marilyn Strathern (1988, 1992), as this object (TM-401-86) consisted of several elements that over the years circulated in divergent trajectories like a “partible person.” This object, collected in 1903 by Claudius H. de Goeje—a naval cartographer with language skills and a personal interest in local cultures—is only part of a device that was, in turn, only one of two devices (Fig. 1). Furthermore, of the composite object collected, one element (TM-401-86b) has been deaccessioned. In this sense, the object under study is a partible thing with a complex cultural biography, wherein each component proceeded in divergent trajectories.

6 On December 16, 1903, during the Dutch Gonini expedition (Fransschen-Herderschee 1905), this object (TM-401-86)—part of a shaman’s device (Figs. 1 and 2)—was collected in the indigenous Wayana village of Panapi, Aletani, Suriname.3 Together with other ethnographic objects collected during this expedition, it was then transported to Paramaribo, the capital of Suriname, from where it was shipped to the Netherlands. In 1904, the ethnographic objects of the Gonini expedition, together with objects from two other expeditions in Suriname, were sent on temporary loan to the Rijks Ethnographisch Museum in Leiden (today: Museum Volkenkunde) pending a definitive decision about the future of this collection.4 In 1908, while selecting objects for further study, de Goejenoted the presence of fungus on several objects that he had so painstakingly collected and brought across the Atlantic Ocean.5 Twenty years later, in October 1927, the ethnographic collections of the 1903 Gonini expedition, the 1904 Tapanahoni expedition, and the 1907 Tumuc-Humac expedition were handed over to the Koloniaal Instituut in Amsterdam (today: Tropenmuseum). Although de Goeje’s complementary notebooks containing the descriptions of each ethnographic object collected were promised to the Tropenmuseum in a letter dated September 13, 1927,6 these notebooks remained in the Rijks Ethnographisch Museum (MuseumVolkenkunde, Leiden: series archive 1443). In 2014, the Tropenmuseum, Amsterdam (KIT), and the RijksMuseumVolkenkunde, Leiden (RMV)—together with the Afrika Museum, Berg en Dal—merged into the Dutch Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen (NMVW) and the inventory numbers at the Tropenmuseum received the prefix TM.

Tropenmuseum Object With Inventory Number 401-86

7 The online collection database of the Tropenmuseum (http://collectie.tropenmuseum.nl/; accessed May 28, 2012), and more recently the online collection database of the new Dutch Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen (http://collectie.wereldculturen.nl/; accessed Nov. 28, 2015), provide the following information on the object under study:

- Accession number: TM-401-86a

- Provenance: Gonini (sic.: Aletani), Suriname

- Date: before 1903 (sic.: 1903)

- Name: a tree-bark cloak for spirits incantation as part of a pono-dance costume (my translation).7

- Indigenous name: Pidaie pitjoe (sic.: pïjai pitpë)

- Dimensions: circa 95 x 14 centimeters (37 3/8 x 5 1/2 inches)

- And I would like to add:

- Material: inner bark of the Tauari (Couratari guianensis)

- Field collector: Claudius H. de Goeje

- Provenance: village of Panapi, Aletani, Suriname, South America

- Culture: Wayana

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 28 There is no simple way to explain object TM-401-86. Of this artifact there remains only the cloak of bark streamers (401-86a; Fig. 2C), as the double-chambered bottle-gourd (tutpë; Lagenaria siceraria; Fig. 2B) with inventory number 401-86b, has been de-accessioned. Both the cloak (TM-401-86a) and the gourd (TM-401-86b) are depicted in de Goeje’s (1906, plate VII, number 16) Bijdrage tot de Ethnographie der Surinaamsche Indianen (Fig. 2A). This illustration offers an impression of how the cloak was attached around the constricted joining between the two chambers of the bottle-gourd. TM- 401-86a is referred to in the online collection database as “a tree-bark cloak for summoning of the spirits as part of a pono-dance costume” (my translation), the enigmatic meaning of which will be explained throughout this article.

9 Based on the original drawings (Fig. 1), this cloak attached to a bottle-gourd was only part of the shaman’s device and hung from a supporting stick: a three-to-four-meter long debarked sapling that was decorated (black with red spirals). The drawings and descriptions further state that there was a second shaman’s device (named pasiépoele by de Goeje; pasik epule): consisting of a similarly debarked and decorated stick (epule), surmounted by two red tail-feathers from a macaw (pasik), to which tips were attached, by means of a cotton string, pieces of bone, or crab carapace. It appears that neither the supporting stick of the cloak-and-gourd device, nor the entire second shaman’s device with macaw feathers, was collected.

10 Regarding the indigenous Wayana name of object TM-401-86, there is a discrepancy between the primary sources and the online collection database. The 1903 object notebook—in the handwriting of the field collector Claudius H. de Goeje—listed this object as piaiepitpé and specified that the cloak of bark streamers was named “noeklah” (in his diary, de Goeje wrote “noeclat”). The report on the Gonini expedition (Fransschen-Herderschee 1905: 138) named this instrument piai petpé (Fig. 1). The entry in the online collection database reads Pidaie pitjoe which in all probability is a double typographical error.8 The report of the Gonini expedition (Fransschen-Herderschee 1905: 138) stated that the cloak of bark streamers is called noek’la. Wayana today name this cloak of bark streamers okalat after the okalat tree (Tauari or Ingi-pipa; Couratari guianensis), from which the inner bark streamers originate. Noeclat, noeklah, and noek’la are variations of the same word, and share its root with okalat. This variation is common in the process of transcribing spoken indigenous languages. Piai [pïjai] is the indigenous Wayana term for “shaman” and pitpé (pitpë) means “skin” or “bark”; hence pïjai pitpë means “the bark—designating the okalat bark streamers—of the shaman.” Piaiepitpé or piai petpé, is thus a description of this device rather than its proper name, which may explain why in his personal diary de Goeje did not write down the name of the complete device.

11 In addition to “tree-bark cloak” (as discussed above) there is another enigmatic element in the description in the online collection database, namely that it is “part of a pono-dance costume.” To understand the meaning of this reference to the pono-dance, we have to go beyond the information provided by the report of the Gonini expedition, the 1903 object notebooks, and even beyond the diary of C. H. de Goeje. This reference to the pono-dance costume can be understood by drawing on my in-depth and long-term study of Wayana history and social memory related to this pono-dance (Duin 2014). In a moment, I will discuss this pono-dance costume and its relation to TM-401-86.

12 Last but not least, there exists a discrepancy between the online collection database and the primary sources pertaining to the provenance or place of origin of the ethnographic objects collected and discussed in this article. The original aim of the Gonini expedition, as its name implies, was to explore the Gonini, a tributary of the Maroni River. However, because the Gonini did not have its sources in the Tumuc-Humac Mountains, as was assumed, the expedition went subsequently up the Maroni River to explore and map the Aletani, the boundary river between Suriname and French Guiana (Fransschen-Herderschee 1905). After mapping the Tumuc-Humac Mountains (the watershed and border between Suriname and Brazil), the expedition members had returned toward the coast of Suriname. On December 16, 1903, the expedition reached the indigenous Wayana village of Panapi, where the expedition members would stay the night. The village of Panapi was located almost 200 kilometer south of where the Gonini enters the Lawa (stretch of river between the Maroni and the Aletani; all belonging to the main course of the Maroni River). Claudius H. de Goeje, the cartographer of the expedition with language skills and a personal interest in local cultures, entered the village and coincidentally witnessed a healing ceremony. TM-401-86a was an element from one of the devices used during this healing ceremony, and it was acquired on this occasion. So, and this is important to note, although the name of the Dutch national geographic expedition was the Gonini expedition, the actual objects were collected not along the Gonini, but instead along the Aletani.9 For a curator recording the provenance of the object under study, it would have been easy to assign this particular object to the Gonini, rather than the actual location near an indigenous Wayana village located about 200 kilometers south of the Gonini. In outlining the similarities and discrepancies in the primary sources—beginning with the expedition report, the object notebook, and finally the field collector’s personal diary—I will explore how this intriguing cloak made from bark streamers and used during the pono-dance became an element in a shaman’s device.

Costume for thePono-Dance

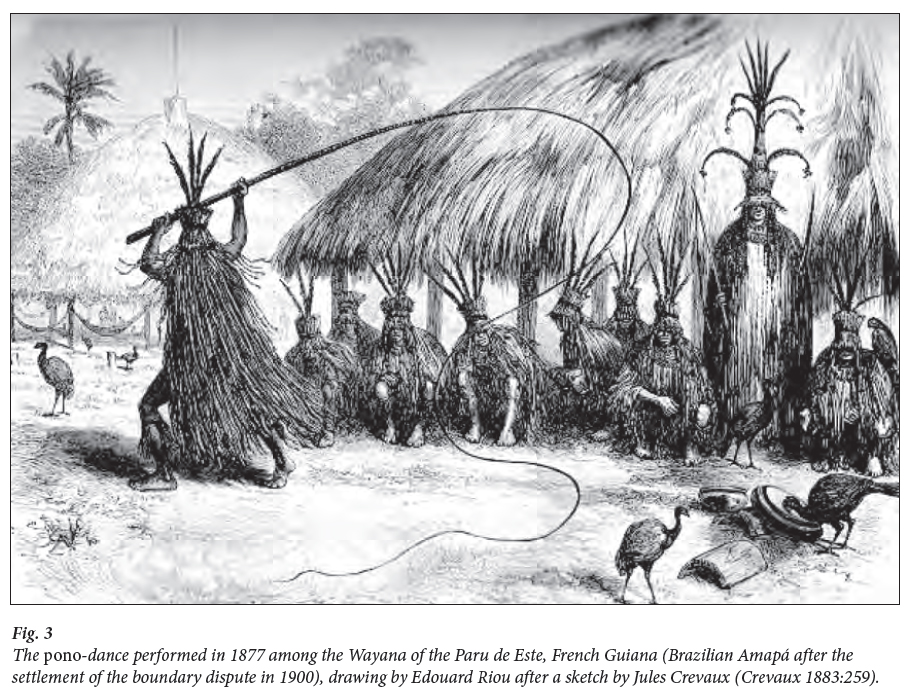

13 Because of the reference to the pono-dance costume, which is not further elaborated upon in either the object description or in the primary sources related to this object, I will briefly discuss the pono-dance and its costume (for more, see Duin 2014).

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 314 Jules Crevaux (1883: 258-59) witnessed this dance performance in the Wayana village of Canéapo, Paru de Este, on October 28, 1878 (Fig. 3). Prior to his departure from this village, Crevaux purchased one of the dance costumes, which is currently curated in the collections of the Musée du Quai Branly, Paris, France (MQB inventory number 71.1881.34.389), and this object indeed resembles TM-401-86a. The object curated in the Musée du Quai Branly is described as a “costume de danse en lianes,” although this dance costume does not consist of liana vines, but of okalat inner bark streamers, analogues TM-401-86a. Its length of 90 centimetres is about the same as the length of the cloak at the Tropenmuseum.10

15 Crevaux described this dance, and wrote that in the village of Chief Canea “all men wear long bark streamers beginning at the neck, and a kind of robe similar to that used by judges. A single man is standing, holding in his hand a whip of which the cord is eight meters long; he turns upon himself and hits the ground with his right foot, then, lifting his whip, he bends his body backwards, and, with a sudden move, projects the cord that cracks like a gunshot (see Fig. 3). At each person their turn to produce these bangs. This dance is called the dance of the pono” (Crevaux 1883: 258; my translation).11 The man standing in the row of squatting people has a large feather headdress (olok) that Crevaux (245) had described earlier. It was, as I will address in a moment, this monumental feather headdress that de Goeje was eager to see.

16 The description by Crevaux, the accompanying engraving (Fig. 3), and the object collected (MQB inventory number 71.1881.34.389), do indeed bear resemblance to the object that was described and collected about thirty years later by de Goeje during the 1903 Gonini expedition, and which is discussed in this article. However, in 1903 this cloak of bark streamers was being used in an entirely different context: not in a dance but instead in a shaman’s session. This brings us to the question how this part of the pono-dance costume became part of a shaman’s device.

Extracts from the Gonini Expedition Report12

17 In order to answer the question how a part of the pono-dance costume, became part of a shaman’s device , it is necessary to know the context in which this object (TM-401-86) was collected in the field. The diary and the object notebook—both written by Claudius H. de Goeje, and discussed in a moment—form the basis of this section of the Gonini expedition report written by expedition leader Alphons Franssen-Herderschee (1905), although there are some additional elements. In the afternoon of December 16, 1903, the expedition arrived in the indigenous Wayana village of Panapi, and initiated an exchange of ethnographic objects for Western trade goods, such as glass beads, knives, mirrors, and fish hooks. Meanwhile,

18 The details deemed necessary by de Goeje, such as the black red-spiraled sticks and the calabash dish with fire, unto which “pits” (sic.: smoked peppers; in Wayana: takupi) producing an eye-tearing smoke,13 are repeated in this expedition report, but seem rather convoluted and are difficult to understand when one is not familiar with Wayana indigenous practices. Noted in this expedition report, and not mentioned by de Goeje, is that Versteeg—the medical doctor of the expedition—had concluded that this patient suffered from malaria. The quinine treatment provided by the medical doctor of the expedition was not deemed adequate by the indigenous people and as they preferred a traditional treatment by the pïjai (shaman). (Even during my fieldwork among the Wayana, about a century after the Gonini expedition, the traditional treatment by the pïjai was preferred over a quinine treatment.) The drawing in the Gonini report (138) is inspired by the drawings and descriptions by de Goeje; other than that, the figure representing the patient is not depicted (Fig. 1). Franschen-Herderschee wrote that the patient was sitting under this device, whereas de Goeje’s drawing in the notebook depicts the patient standing under this device. No further explanation is provided as to why a costume intended for the pono-dance was brought forward.

From the Notebook on the Ethnographic Objects Collected During the Gonini Expedition14

19 The object under study (TM-401-86) was entered as the last entry (object number 49) in the notebook on the ethnographic objects collected during the 1903 Gonini expedition (RMV series archive 1443). These entries were handwritten by the field collector Claudius de Goeje.

The notebook entry for “object number 49” concludes with the statement that

20 This noekla or cloak of bark streamers used during the pono-dance has been discussed earlier, yet the reason why it was included in this shaman’s device is not explained either in this notebook entry. Most important in this notebook is the detailed description of the sticks that were not collected, the deaccessioned gourd, the decoration of both sticks and gourd, the use of the device, and the orientation of both instrument and patient toward the rising sun. The concluding statement on the pono-dance costume confuses rather than clarifies the meaning of this device.

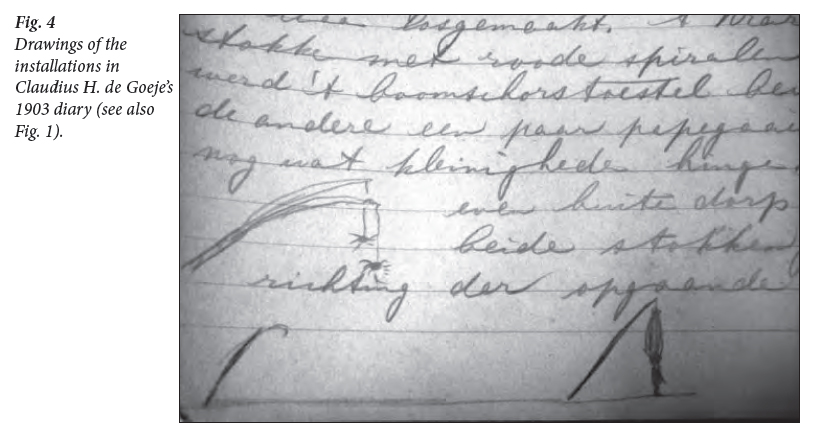

From the Original 1903 Diary of Claudius H. de Goeje17

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 422 This section from personal diary of the field collector Claudius de Goeje, together with his description in the object notebook, was used by expedition leader Franssen-Herderschee to write the section in the official report of the Gonini expedition (as discussed earlier). There are, however, some obvious discrepancies that need to be addressed. First and foremost is the dissimilar attitude towards the indigenous people. De Goeje seems more engaged with the local indigenous people and he is interested in their native language and customs. Whereas de Goeje stated neutrally that some words were pronounced by the pijai, Franschen-Herderschee stated that these were “magic” words (tooverwoorden). Furthermore, de Goeje mentioned that pïjai Jaloe was the brother of Panipi (or Panapi?) and that he spoke Trio (both the Trio and Wayana language are of the Carib stock). There is also mention of an Emerillon woman in the village. Emerillon or Teko (who are Tupi-speakers), Trio (Tïliyo), and Wayana are neighboring indigenous peoples. Additionally, de Goeje stated that these shaman’s devices were positioned outside the village, and based on his concluding paragraph it can be deduced that the devices were not placed on the water side, but rather towards the forest side of the village.

23 Most significant, and not mentioned in the other sources, is that de Goeje in his personal diary noted that he asked his informant about the dancing gear. Most likely he was eager to see a monumental olok feather headdress, emblematic for the Wayana, but instead a cloak made from bark streamers was retrieved. De Goeje was familiar with this kind of object through his studies of Voyages dans l’Amérique du Sud in which Jules Crevaux (1883: 258-59) described a similar object in the context of the pono-dance (as discussed earlier). It was this object (okalat; de Goeje wrote noeclat and noekla) that was subsequently used by pïjai Jaloe during his session. That de Goeje requested to see dancing gear explains his references to the pono-dance that are mentioned in his diary, the object notebook, and the expedition report, but these brief references are not further elaborated upon. Awareness of this request could be instrumental in understanding how a cloak characteristic of the pono-dance became, in 1903, part of a shaman’s device.

24 It was only after de Goeje had asked to see dancing gear that the cloak used for the pono-dance was brought forward. De Goeje most likely discussed the pono-dance with pïjai Jaloe which brings forth the question: did pïjai Jaloe, after this discussion on the pono-dance, decide that this trapping of the pono-dance costume could aid him in his search for the spirit responsible for the patient’s illness?18 (Which was actually malaria, according to the medical doctor of the expedition.) I have argued elsewhere (Duin 2014) that the condition in which the pono-dance functioned was during times of widespread disease and pandemic death, so we see that the connection with illness was already there. But, prior to his discussions with de Goeje, had the pïjai intended to use this object for his upcoming session? Or did the discussions of the pono-dance bring forth the idea for this unintended use of the cloak? We will never know if it was de Goeje’s request to see the dancing gear that prompted the use of TM-401-86a during the shaman’s session he witnessed and described, but it was so used, and then added to the expedition’s collection of ethnographica, and subsequently brought back to the Netherlands, where it is at present curated in the Topenmuseum, Amsterdam.

Object Biographies, a “Dividual” Body, and Partible Objects

25 According to Kopytoff (1986), objects have a constantly emerging cultural biography in which non-commodities can become commodities, and later a non-commodity again. The original dance-costume (non-commodity) was traded to the Dutch during the 1903 Gonini expedition (commodity), and is currently curated in the Tropenmuseum (non-commodity). The biography of this particular object is however more complex. Regarding this object, there are various original sources that describe this object, notably the report of the Gonini expedition, the original object notebook, and the original diary of de Goeje. Based on the detailed descriptions of the black red-spiraled sticks (not collected), the double-chambered bottle-gourd (401-86b, deaccessioned), and the cloak from inner-bark streamers (TM-401-86a), this shaman’s device (pïjai pitpë) can be reconstructed and provides a very clear image of the complete device. Nevertheless, even these primary sources only provide a partial understanding of the object, unless we pair the description of the object with a comprehensive understanding of the relevant indigenous culture. Without a proper background on the pono-dance, as briefly outlined in this article (it is outside the scope of this article to properly discuss this whip-dance in detail; see Duin 2014), the discussion of this object remains rather enigmatic. The description: “a tree-bark cloak for spirits incantation (summoning of the spirits) as part of a pono-dance costume” (my translation), although rather enigmatic at first, is actually very accurate, though it needs the further contextualization I have provided in this article.

26 During the last decades a large body of literature has accumulated on the personalities,agency, and the biography of objects. Of particular interest to the present article is Marilyn Strathern’s (1988, 1992) socio-anthropological conceptualization of “plural personhood,” whereby intersubjectivity emerging in social interaction is twofold: it is a particular “partible body” in interaction with other bodies; and it is a collective “dividual body” encompassing multiple bodies. The “shaman’s device” piaiepitpé (pïjai pitpë) is a “dividual” body encompassing both the cloak of bark streamers (TM-401-86a), the deaccessioned gourd (TM-401-86b), and the red-and-black supporting sticks (not collected). The cloak of bark streamers is a particular partible body in that it also served as part of a dance costume (whereby the pono-dance costume engenders another collective “dividual” body). The intersubjectivity and plurality of this cloak of bark streamers collected by de Goeje and currently curated on site at the Tropenmuseum (inventory number TM-401-86a), is, I argue, a result of the request by de Goeje to see the local dance gear—as is mentioned only in his personal diary. Albeit this object was used in a shaman’s ritual, we cannot assume that it was normally used so. This may even have been a one-time event. The primary sources referring to this object, combined with a comprehensive understanding of the relevant indigenous culture, provide an exceptional opportunity to re-contextualize the object biography of this partible object. This case study on partible object TM-401-86a demonstrates that it is of utmost important to be familiar with the details of the interaction and context in which took place the collection of an ethnographic object. Yet decisive moments—as demonstrated in this case study—may not have been published or available in the ledgers or object note books, but only available in the personal diaries of the collector. This case study further demonstrates the field collector’s influence, unintended or not, on the process of how a particular ethnographic object was brought together.

First and foremost, I would like to thank the grandchildren of Claudius H. de Goeje, Joannie Bosmans-Borneman and Bernard Borneman, who were so kind to make the original diaries of their grandfather available for research. Secondly, the now retired Friedie Hellemons (head documentalist of material culture, Tropenmuseum), who frequently searched the Tropenmuseum database for answers to my questions pertaining to the Wayana collections. I would like to thank the anonymous reviewers and editorial board of the Material Culture Review/Revue de la Culture Matérielle, at Cape Breton University, for their valuable suggestions. Fine-tuning of this article took place during my Hunt Postdoctoral Fellowship, awarded by the Wenner-Gren Foundation. Last but not least, the Wayana of the Upper Maroni Basin, who always were very interested in sharing and analyzing their history with me. The conclusions, interpretations, and hypothesis, made in this article, however, are my responsibility.