Articles

Tourist Photography in Peru: An Actor-Network Theory Approach to Images Posted Online

Abstract

One of the most common practices tourists perform is taking photographs. In this exploratory study, I examined a sample of 146 pictures which tourists have taken in Peru’s Cusco region and posted online. Drawing on actor-network theory, I approach the destination not as a bounded place but rather as a dynamic network enacted through objects, people, and places. An analysis of the main motifs in the images suggests that tourist photography in Peru actively contributes to the construction of tourist identities and of social differences between visitors and local people.

Résumé

L’une des choses que pratiquent le plus communément les touristes est la prise de photographies. Dans cette étude exploratoire, j’examine un échantillon de 146 photographies prises par des touristes dans la région de Cuzco au Pérou et qui ont été postées en ligne. À partir de la théorie de l’acteur-réseau, j’approche la destination non comme pas comme un lieu délimité, mais plutôt comme un réseau dynamique qui se concrétise au moyen d’objets, de personnes et de lieux. L’analyse des motifs principaux des images indique que la photographie touristique au Pérou contribue activement à la construction des identités des touristes et des différences sociales entre les visiteurs et les habitants de l’endroit.

1 The definition of a tourist as “a temporarily leisured person who voluntarily visits a place away from home for the purpose of experiencing a change” (Smith 1989: 1) is much cited in tourism literature. Arguably, one can add that tourists are also defined by the common practice of taking photographs. Given the visual focus of many tourist activities, photography and tourism have been closely linked (i.e., Sontag 1977). The tourist gaze is further extended and fixed through the production and distribution of photographic images (Urry 1990). While the viewing of existing images and information influences what tourists seek out and choose to document with their cameras, they in turn perpetuate similar motifs and themes with their photographic practice, thus closing a hermeneutic circle of representation (Albers and James 1988; Urry 1990).

2 Photographic technologies and practices have both undergone major changes. With the launch of small and affordable cameras in the late 19th century, the practice of photography was extended from professionals to common people. The more recent arrival of digital cameras now makes possible the instant production of images, while high storage capacities and options for deleting allow for “more casual and ‘experimental’ ways of photographing” (Larsen 2008: 148). Through the digital screen several people can view the photographic processes and resulting images, which facilitates greater sociability and cooperation in picture taking. This social aspect is further extended by options for instantly sharing photos with other Internet and mobile phone users (Larsen 2008; Scifo 2005).

3 Widespread Internet access now allows for updating blogs and websites from almost anywhere (Larsen 2008: 151); “travellers are not only travelling on the internet, but also with the internet” (Molz 2004: 170). While the production and distribution of destination images used to be largely controlled by the tourism industry, digital technologies have made user-generated content far more widely available. This means that a greater range of perspectives can be represented. Travel experience informs online content, and this in turn affects the potential travel decisions of others (Stepchenkova and Zhan 2013). The flow of images has become far more complex and unpredictable (Larsen 2008: 143). Posting travel experiences online can even lead to behaviour changes of travellers themselves, who may choose to engage in certain activities especially for their audience (Molz 2004: 177). While travel websites constitute important tools for maintaining social connections, they also afford opportunities for “interpersonal surveillance,” as travellers’ moves can be monitored more closely (Molz 2006). Rather than viewing online travel sites as fundamentally separate from corporeal travel, Molz highlights the ways in which the two are integrated: “the boundary between the real and the virtual is neither impenetrable nor collapsed, but rather ‘in play,’ criss-crossed by a series of practices, mobilities, metaphors, and meanings” (2004: 175).

4 Though it has been around since the 1980s, actor-network theory (ANT) has only recently been embraced by tourism researchers in order to achieve a more dynamic and holistic understanding of tourism processes. This approach directs us toward “seeing a destination not only as a metaphor for place, but also as a place that is performed for and by tourists” (Bærenholdt 2012: 116-17). Photography can thus be understood not simply as a recording of tourism destinations but as playing an important part in creating them. Strolling around the central plaza of the city of Cusco in the southern Peruvian Andes, one can see tourists stopping and taking photos everywhere. The city attracts tourists with its mountain scenery, colonial and Inca architecture, and colourful indigenous culture; not surprisingly, these motifs are frequently photographed.

5 Approaching the destination as a network performed by human and non-human actors opens up different views of photography. In this exploratory study, I examine a sample of 146 tourist photographs from the Cusco area that tourists have posted on an online photo-sharing platform. Drawing largely on ANT and content analysis, I examine what themes may be portrayed or captured in these images and what this can reveal about tourist experiences and power relations. This paper begins by situating ANT in the broader theoretical developments of tourism research and showing how it can be applied to tourist photography. This is followed by a brief overview of tourism issues in Peru and an outline of the study’s methods and findings. In the discussion, I consider the results in the broader context of ANT and in relation to other data; this section will also address some of ANT’s potential limitations in this context as well as its possibilities for further applications in the study of travel photography.

Actor-Network Theory and Tourism

6 Tourism research only began to develop seriously after the advent of mass tourism in the 1970s. Early theorizing about tourism generally employed structural binaries such as hosts versus guests, authentic versus staged, and everyday versus extraordinary experiences. MacCannell, for example, described how cultural materials and practices become rearranged and presented to tourists in a form of “staged authenticity” (1976). Other researchers have analyzed tourism as a rite of passage, emphasizing how the journey temporarily moves people into a liminal place where many cultural norms from home are suspended (Turner 1982; Graburn 1989, 2004). Tourists were generally seen as turning away from the everyday in search of more authentic, sacred, and extraordinary experiences. While these approaches successfully illuminate certain aspects of tourism, they have been criticized for taking many phenomena as pre-existing rather than examining how exactly they are constructed and negotiated (Bærenholdt et al. 2004; Franklin 2004). This critique has resulted in the so-called performance turn in tourism studies. Similar to

7 Butler’s view of gender norms as active performance rather than pre-existing entities (1990), this theoretical development understands tourist practices and relations as emerging through performance and negotiation (Bærenholdt et al. 2004; Uriely 2005; Urry and Larsen 2011).

8 More recently, this approach has been developed further by incorporating ANT into tourism studies. First developed in the 1980s for the study of technology in society, ANT challenges traditional analytical dichotomies such as social versus material and structure versus agency, and focuses instead on the underlying processes that bring about these distinctions (Law 1992; Latour 2005: 64-65). Law views social structure not as a stable framework but as “a site of struggle, a relational effect that recursively generates and reproduces itself” (Law 1992: 5). Since social interactions are virtually always mediated by objects, ANT proposes that the social and the material have to be analyzed together (Callon and Latour 1981; Law 1992: 3).

9 One of the key concepts used to accomplish this is the network. Action is not seen as resulting autonomously from different actors but rather as depending on a heterogeneous network of relationships between human and non-human actors (Law 1992: 4; Latour 2005). Latour points out that the concept of the network has frequently been misunderstood as referring to channels of communication between stable parts, yet the metaphor of the network was originally meant to refer to a series of transformations that the actors, or actants, undergo in relation to each other (Latour1999: 15-16). These translations produce ordering effects in the network, andso the analysis of these ordering processes and resulting struggles becomes a key focus of ANT (Law 1992, 1994).

10 In the context of tourism, ANT directs us to understand the destination not as a bounded place, but as a dynamic network enacted through objects, people, and places (Ren 2010a, 2010b; Franklin 2004; van der Duim 2005; Bærenholdt 2012). Following Latour (2005), Bærenholdt argues that “space and place are no longer just containers surrounding practices,” but rather “destinations emerge ... as something made and ‘glued together’ as an assemblage of human and non-human actors” (2012: 112-13). Similarly, Franklin approaches tourism networks as “mutually constitutive, rhizomic, joined in processes of becoming or ‘emergent,’ always shedding parts of themselves and attaching to others” (2004: 284). Based on the premise that the social is always enacted through the material, ANT seeks to investigate how relations become established in more stable and material forms and thus develop more consistent and lasting patterns (Law and Mol 2001). ANT draws on Foucauldian understandings of power, and the processes of ordering in a network can be compared to the effects of discourses (Foucault 1972, 1980; Law 1992: 7). Identifying these discourses, then, can help us analyze relationships of power, which van der Duim regards as a major contribution of ANT to tourism studies (2005: 972). A few tourism studies have used non-human actors as their entry point for analysis. Ren, for example, has focused on a smoked cheese and the different forms in which it gets produced and marketed to tourists in a small Polish town (2010a). Simoni has examined the role of Cuban cigars, including their sites of production as well as the formal and informal strategies of their distribution (2012). Allowing for the inclusion of non-human actors can provide new approaches for understanding the complex interactions in the tourism network.

11 More recent developments of ANT have included variations on the network by proposing new analytical concepts, such as fluid and fire (Law and Mol 2001). The concept of fire highlights the “flickering relation between presence and absence” (615) and directs our attention toward the impact of absent entities on the processes of ordering. Absence can play different roles. In his analysis of a medieval tourist centre in Denmark, Bærenholdt emphasizes how the absence of the past is actively implied in the site, thus “the presence of some configurations depends on the absence of others” (2012: 116). Conversely, tourism almost always involves the active hiding of certain elements. In tourist brochures of Hawaii, for example, local people are usually depicted with nature as a pristine-looking backdrop, while their participation in modern life and the far-reaching environmental changes are left out (Desmond 1999). In tourism, then, the “actor-network is constructed ... through absences and presences, muting and excluding some practices, voices and knowledges rather than others” (Ren et al. 2012: 18).

12 Thus, the focus on performance in general and ANT in particular adds useful theoretical alternatives to the older more structural and static approaches. Using an ANT approach,

13 In my analysis of tourists’ photographs, I draw primarily on ANT’s concepts of translation and ordering. Through photography, tourists document and stage some of their experiences, and as a result different objects, people, and places assume more stable associations in the form of images. Jóhannesson writes that “tourists can be conceived as being both translators and translated.... They translate tourist places through their performances, for example by taking photos.... Here the photo becomes the intermediary into which the place is translated” (2005: 140). Photography thus emerges as an important tool for the ordering and shaping the tourism network. The photograph itself is an object and functions as an actor in other networks, i.e., remembering (Scarles 2008). What I investigate in this paper, however, are the assemblages of materials, people, and places within the photos, and what these temporarily stabilized networks can tell us about tourists’ experiences and power relations.

Tourism in Peru

14 Peru is the most visited Andean country. Nine per cent of Peru’s employment is now in the tourism sector; this figure has doubled since 1990 (WTTC 2014). In 2011, one million tourists visited the Inca citadel of Machu Picchu, South America’s most popular attraction (Andean Air Mail and Peruvian Times 2011), and Cusco, the former capital of the Inca Empire, was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site based on its combination of Inca and Spanish colonial architecture.

15 Due to their colonial history, populations across Latin America today show a heterogeneous mix of Spanish and indigenous ancestry. Andean people are usually divided into three broad categories: White1 ; mestizo, referring to a person of mixed European and indigenous origin; and Indian or indigenous. Indigenous academics like Corntassel (2003) argue for people’s rights to define themselves, yet based on political and ideological grounds, definitions of indigeneity tend to be variable and contentious (de la Cadena and Starn 2007; Gomes 2013; Merlan 2009). Merlan distinguishes between definitions that are “criterial,” seeking to establish identifying characteristics, and those that are “relational,” focusing on the ways in which social context shapes indigeneity (2009: 304). Rather than essential characteristics, it is the relationship between the group and the state (Maybury-Lewis 1997: 54), or the contrast with what is considered non-indigenous (de la Cadena and Starn 2007: 4), which shapes understandings of indigenous identity.

16 In the Andes, ethnic definitions are clearly relational; definitions vary not only from region to region, but also between different parts of the population and even individuals (Colloredo-Mansfeld 1998, 1999; Weismantel 2001; Mitchell 2006). Distinctions are based less on phenotypic differences, which are not very prominent, than on cultural and socio-economic markers like education, occupation, and clothing. Thus, by changing some of these characteristics, people can manipulate how others perceive their ethnic identities. The pressure to do so is high, as the constructs of race are powerful and continue to fuel discrimination across the Andes (Colloredo-Mansfeld 1999; Weismantel 1988, 2001). Even though indigenous culture constitutes one of the major attractions for tourists, it is mostly mestizo and White middlemen who benefit from the business (van den Berghe and Flores Ochoa 2000; Weismantel 2001; Henrici 2007).

17 Tourism can also lead to cultural loss. For example, Henrici describes how the colourful fringes along indigenous women’s hats have traditionally signalled their social status. Now young girls are increasingly wearing multiple colours, sometimes including those traditionally assigned to adult women and meant to indicate readiness for marriage, in order to pose for photos. As a result of this, people in many indigenous communities surrounding Pisac, near Cusco, no longer know the traditional meaning of the colours (2007). However, it is important to note that local people can often exercise significant agency by choosing what to display for tourists (Cheong and Miller 2000; Weismantel 2001; Stronza 2001; Bruner 2004). Maoz’s work in India, for example, has shown how locals use a variety of strategies to manage tourism interactions, including trying to educate tourists through signs and consciously staging fake spirituality (2006).

Methods

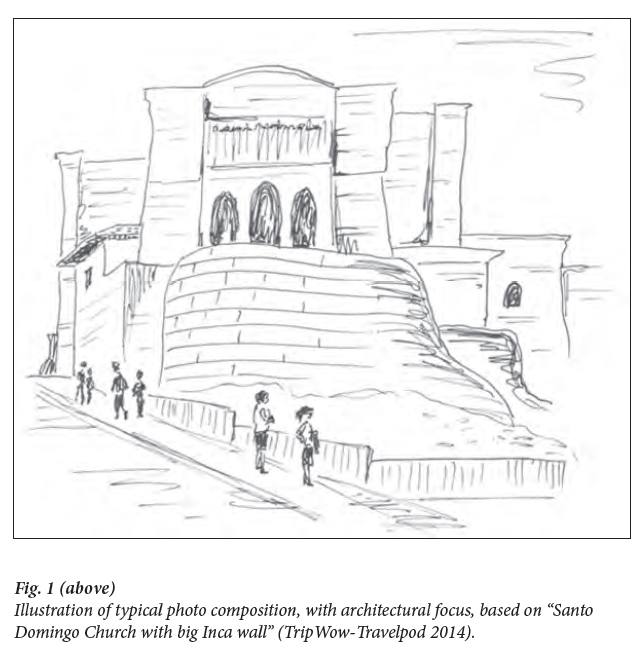

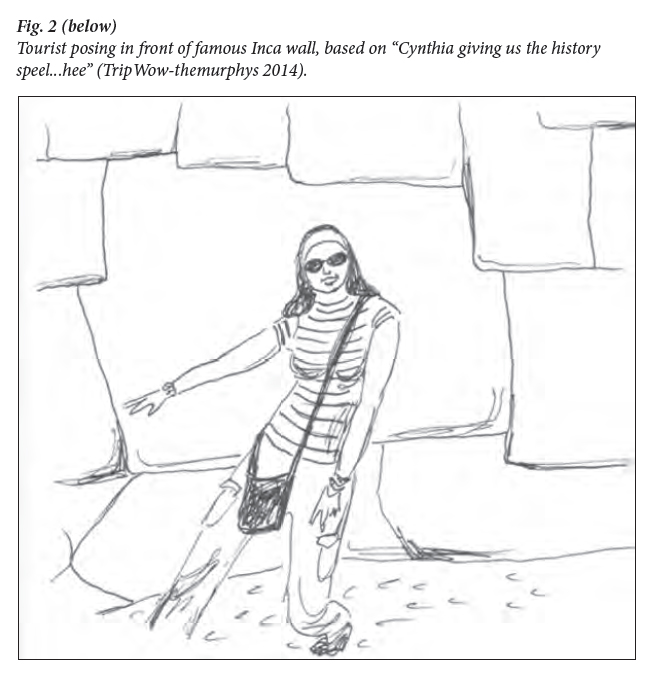

18 My search for tourist photos online led me to TripWow, a website that is part of Tripadvisor, and allows travellers to post their photos in a fluid slideshow that includes background music and maps (TripWow 2014). I selected seven slideshows from those shown near the top of the list of “popular slideshows of Cusco.” Many of the slideshows posted under the heading Cusco actually include pictures from a range of different places, so I focused on those with pictures taken mainly in and near the city, almost all of them in places I am familiar with. The seven slideshows contain between 13 and 24 images each, adding up to a total of 146. The first slideshow is put together by the website organizers and is made up of pictures contributed by different travellers. This official version is the first to come up in a search and was presumably put together to present a well-rounded image of the area; in that sense its arrangement presents another level of ordering. As judged by the names posted (i.e., jeffsadventures, globetrekker, carlaandmike), the other six slideshows are assembled by individual travellers or couples. I do not have permission to reproduce the photos here, but the slideshows can be viewed through the links listed in the references. In addition, I have included line drawings based on a few of the photos in order to illustrate some of the typical motifs.

19 To complement ANT, I draw on content analysis and, to a lesser degree, on semiotic and critical analysis. Content analysis is descriptive in nature and identifies the main subjects and “focal themes” of images (Albers and James 1988). Similar to other analyses of tourist images (Albers and James 1988; Caton and Almeida Santos 2008; Dann 1996), my content categories are based on the people depicted, the activities they are engaged in, and the main settings and background features. The categories are broad: for example, “architecture” includes Inca and pre-Inca ruins as well as cityscape, and “nature” refers to wilderness as well as cultivated land. In table 1, below, the category “local people” includes both those appearing indigenous and non-indigenous, while in table 2 they are further differentiated. As outlined earlier, definitions of indigeneity in the Andes are relational and context-dependent, but despite the complexities, the binary between White and indigenous is consistently re-enacted and thereby reproduced (Weismantel 2001). Similarly, tourists are likely more interested in the visible markers of indigeneity, and in the absence of other identifiable characteristics such as language or occupation; I base my distinction on these traits as well. So, while I am clearly using a simplifying binary, I believe that this distinction reflects the views of most tourists. In their analysis of ethnic representations in postcards, Albers and James relied on a similar distinction (1988: 145-46).

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1 Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 220 Other categories created challenges, too. For example, since Cusco is a busy tourist destination, many images of architectural sites include tourists as well. If the tourists were not clearly the focus of the picture but seemed to be mostly in the background, I decided to classify the image as “architecture” (cf. Fig. 1, below), whereas if tourists were in the foreground and/or clearly posing, it would be categorized as “architecture & tourists” (see Fig. 2). Similarly, a view of the Urubamba Valley, with the town of Pisac at the bottom making up less than a quarter of the image, could be classified as either “architecture” or “nature.” When in doubt, I followed the captions of the photo, so if titled “view of the Urubamba Valley” or “beautiful mountain valley,” it was classified as “nature,” whereas if named “town of Pisac” it would be listed under “architecture.” Even though these categories are quite general, they can provide a good overview and general content analysis of the images.

21 The semiotic approach goes further by looking at symbolic meanings; it is a “method of contrast and comparison that discovers the structures which link particular elements together in a recurring fashion, and that demonstrates how these structures code and generate a set of meanings or a message” (Albers and James 1988: 149). It does not approach photography as mirroring nature but as a specific “way of seeing” that is shaped by, and in turn perpetuates, existing social ideologies and discourses (Berger 1972: 10). Through its focus on social factors, semiotic analysis also emphasizes continuities between analogue and digital photography (Larsen 2008: 144). Last, a critical view leads us to a consideration of power structures, and of whose interests are reflected, perpetuated, or challenged through specific depictions (Albers and James 1988: 150; Caton and Almeida Santos 2008). With any approach to analyzing images it is important to remember that meanings are not fixed and that multiple understandings are always possible (Albers and James 1988: 142; Sontag 1977).

Results

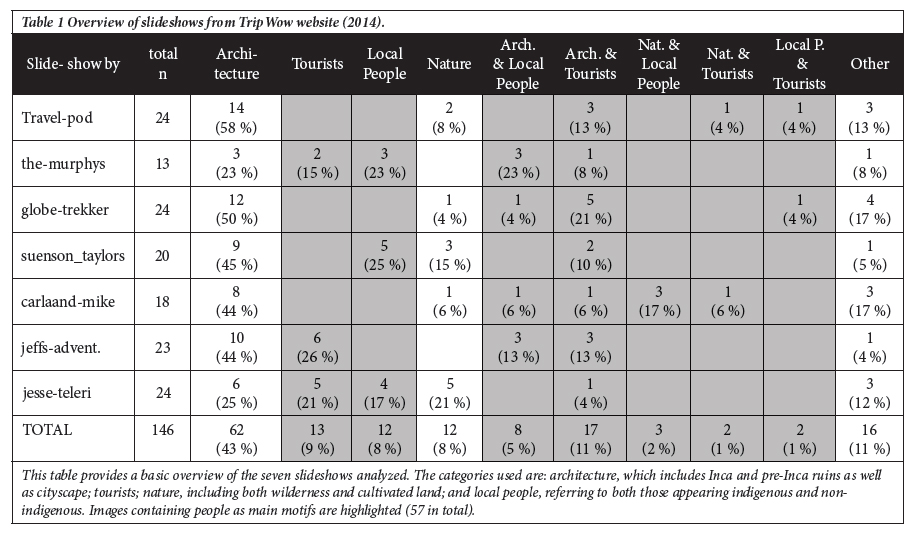

22 As table 1 below illustrates, the majority of photos (43 per cent) are of architectural features with people playing no or only minor roles; this is true for the sample as a whole as well as for each individual slideshow except no. 2, which has an equal number of photos of “architecture,” “local people,” and “architecture and local people.” “Architecture and tourists” constitutes the second-largest category of the sample as a whole (11 per cent), followed by “tourists” (9 per cent), “local people” (8 per cent), and “nature” (8 per cent). While every slideshow includes images of “architecture” and “architecture and tourists,” there is greater variation in the other categories. For example, “local people” as a main focus appear in images of three slideshows only, but not at all in the other four. Every slideshow contains at least one image that does not fit into any of the categories and is thus grouped as “other”; these include, most commonly, parts of museum exhibits, food, drink, and inside views of restaurants.

23 Table 1 provides a basic overview of the seven slideshows analyzed. The categories used are: architecture, which includes Inca and pre-Inca ruins as well as cityscape; tourists; nature, including both wilderness and cultivated land; and local people, referring to both those appearing indigenous and non-indigenous. Images containing people as main motifs are highlighted (57 in total).

Display large image of Figure 3

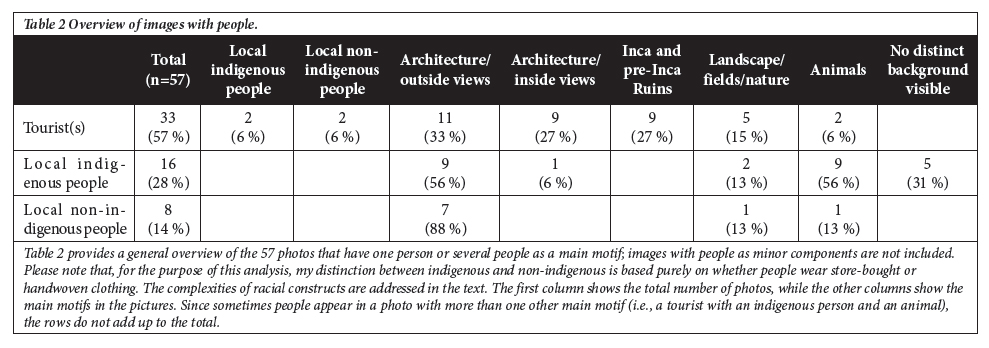

Display large image of Figure 324 Rather than showing a breakdown for each slideshow, table 2 summarizes the sample as a whole. What emerges clearly is that the people depicted most often in tourists’ photographs are the tourists themselves (57 per cent of the total). Tourists were most likely to take photos of themselves or each other near urban architectural features (33 per cent), closely followed by themselves depicted inside buildings (27 per cent), and in Inca or pre-Inca sites (27 per cent) (see Fig. 2.). Indigenous people were the second-most common category of people photographed (28 per cent of the total), most often outside of architectural features (56 per cent), without distinct backgrounds visible (31 per cent) (see Fig. 3) and with animals (25 per cent). Local people without clear indigenous markers are the least common (14 per cent of the total), and are overwhelmingly pictured with architecture (88 per cent). What is not shown in table 2 is that non-indigenous people appear in only two of the seven slideshows. It is also worth noting that four of the eight photos of non-indigenous people show children.

25 Semiotic analysis seeks to contextualize images with associated writings (Albers and James 1988: 147). The slideshows all include titles or short descriptions for each photo. I do not relate the text to the overall focus of the different slideshows or attempt a detailed categorization; my goal here is simply to give a few examples that reflect the range of the tourists’ knowledge and attitudes. Most of the titles are descriptive, usually naming the location in which the image was taken, such as “Santa Domingo Church with big Inca wall” (TripWow-Travelpod 2014), in Fig. 1, or “Plaza de Armas in Cusco” (TripWowcarlaandmike 2014). The level of descriptions varies between quite specific and very vague; photos of the same statue, for example, are alternatively described as “statue of Inca leader Pachacuti” (TripWow-globetrekker 2014) and “monument man” (TripWow-jesseteleri 2014). Some descriptions reflect additional knowledge the tourists have, such as “Coca Leaves for Altitude Adjustment” (TripWow-globetrekker 2014), about a cup of coca tea, or “Spanish influence on the balconies” (TripWow-suenson_taylors 2014), describing the architecture around Cusco’s main square. Tourists’ personal judgements also appear in some titles, such as “amazing Inca stonework” (TripWow-jeffsadventures 2014) for a photo of an Inca wall, or “Rest Time from Hassling the Tourists” (TripWow-themurphys 2014) for a picture of traditionally dressed women sitting with their llamas.

Discussion

26 As outlined above, ANT allows us to approach tourism as actively performed. By turning tourist experience into a more durable form that can be distributed and shared, photography is arguably a prominent form of ordering (Jóhannesson 2005). Bærenholdt et al. state that “tourist photography performances ... are scripted by, and acted out, in response to dominant ‘tourist gazes’ and mythologies that circulate in photo albums and the ‘imagescapes’ of television, films, magazines and so on” (2004: 70). Based on this, we can ask what elements are given durable form in the photographs. Which elements are present andwhich are absent? Through these assemblages of people, objects, and places, which kinds of “tourist gazes” and discourses are tourists enacting and/or challenging in their photos?

27 Almost half of the photos in the sample as a whole (43 per cent) do not include people in a prominent way, but are instead focused on Spanish, Inca, or pre-Inca architectural features. This emphasis suggests the importance of the physical spaces in the tourists’ experience. In his study of British tourist brochures, Dann found that almost 25 per cent of the pictures did not feature people at all, “thereby highlighting the motif of ‘getting away from it all’” (1996: 63).

28 In my sample, it is interesting to note that, even though most of the sites pictured are quite busy, many photos show few people. I have attempted to take photos without other tourists in them, thereby highlighting the relationship between myself and the place—without the intrusion of others. Similarly, Bærenholdt et al. observed that tourists photographing the Danish castle ruin Hammershus often went to great length to avoid other tourists. The other tourists are made absent to maintain the romantic notion of the place as pristine and timeless (2004). This fits with the search for authenticity and the sacred (MacCannell 1976; Turner 1982; Graburn 1989, 2004), and could be seen as “tourists enacting” the adventure discourse of the brave, solitary explorer travelling independently to faraway places. Dating back to colonial history, this discourse emphasizes activity, bravery, self-reliance and a romanticizing gaze (Dubois 1995; Elsrud 2006), while also reflecting the continuities between colonialism, imperialism, and tourism (Nash 1989).

29 It is noticeable that it is mostly the main tourist attractions in and around the main square that appear in tourists’ photographs, such as the two cathedrals, the Church of Santo Domingo, and the ruins of Saqsayhuaman. Some slideshows (TripWow-carlaandmike 2014, TripWow-suenson_taylors 2014) include shots of the older cobbled streets and smaller squares near the centre, but in all the slideshows other areas of Cusco, such as the nearby markets, railway, and residential areas, remain completely absent. As far as the photos indicate, tourists stay very much near the centre and, even if they venture elsewhere, tend not to take pictures there, or at least not share them online. Thus, while on the one hand tourists may be performing part of the romantic, adventure discourse in their photos, on the other hand they very much reproduce the places and situations marketed to them as tourist sights, thereby perpetuating the hermeneutic circle (Albers and James 1988; Urry 1990).

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 430 Apart from the notable absence of people in general, the people that do appear are, most commonly, the tourists themselves. In his study of tourist brochures, Dann found almost nine times more pictures of “tourists only” than of “locals only,” which he argues is “emphasizing advertisers’ support for the normative segregation of hosts from guests” (1996: 63). Less than 10 per cent of images in his sample showed tourists and locals together, which he sees as an indication that “for the media-makers at least, the idea of tourism as a meeting of peoples was somehow not to be encouraged” (Dann 1996: 64). Other studies of travel photos from Peru (Stepchenkova and Zhan 2013) and a study-abroad program that operated in various countries (Caton and Almeida Santos 2008) have found a similar absence of images showing interactions between tourists and locals. While some tourism researchers have emphasized that deeper connections can form between visitors and locals (Wilson and Ateljevic 2008; Ren 2010b), often contacts are described as perfunctory (Graburn 2004; Noy 2004; Maoz 2006) or even exploitative (Abbink 2004; Turton 2004). Van den Berghe views many encounters between tourists and locals as a “parody of human relationship ... epitomized by the classic photograph of the tourist surrounded by costumed natives in a fake display of intimacy and familiarity” (1980: 387). In my sample, only two images show tourists with locals, in both cases indigenous people who, dressed in colourful clothes and accompanied by animals, are clearly posing for money (TripWow-globetrekker 2014; TripWow-Travelpod 2014). The title “Making New Friends in Peru” (TripWow-globetrekker 2014), see Fig. 4, may be ironic or, more likely, an attempt at constructing closeness in a fleeting encounter or “fake display of intimacy” (van den Berghe 1980: 387).

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 531 Where several people are shown together in a photo, these are almost always groups of tourists. In their study at Hammershus, Bærenholdt et al. observed that people spent a lot of time taking photos of family members. This “family gaze,” they argue, “revolves around the production of social relations rather than the consumption of places” (2004: 70). The authors highlight how relationships with “peers, colleagues, family and friends” play an important role in people’s travel experiences (Bærenholdt et al. 2004: 10); notably absent from this list are local people. While the “family gaze” is not evident in the tourists’ photos from Cusco, the emphasis on tourists themselves and fellow travellers, rather than local people, shows up prominently here as well (see Fig. 5). Moreover, the tourists in the photos are almost invariably smiling and appear in pleasant surroundings like sitting in restaurants or standing in front of picturesque churches or ruins. Likewise, Caton and Almeida Santos report that travel-abroad students appear mostly “jovial and triumphant” in their travel photos (2008: 21). Similar to the cheerful spin of the photos, Noy found that the travel narratives of young Israeli backpackers focused strongly on the positive aspects of the journey, while disappointment, fear, and boredom were rarely talked about (2004). Only one of the seven slideshows (TripWow-jesseteleri 2014) includes photos that show tourists in less-than-happy situations: one of a young man with an injured hand in a hospital bed and another of a couple standing in the Pisac ruins in pouring rain—though they are still smiling in the latter.

32 Even though most of the photos are taken within the city of Cusco, what is notable is the absence of people without visible indigenous markers, even though they make up the vast majority of the city’s population. (I was told several times in Cusco that the indigenous-looking people posing for photos either come in from surrounding communities or are locals who dress up in indigenous clothes to make money.) The focus on people with clear indigenous markers fits with the prominent marketing and staging of certain aspects of indigenous culture. While indigenous-looking people are more present in the photos than non-indigenous people, it is also important to look at what is absent in their depictions. As shown in table 2, they almost always appear in outside settings and, in over half of the cases, are accompanied by animals, mostly llamas, alpacas, and lambs. Also, there is not a single image of an indigenous adult man; all the indigenous people are either women or children. In the cases where indigenous women appear without animals, including the single picture taken indoors, the women demonstrate traditional dying and weaving techniques (TripWow-themurphys 2014; TripWow-suenson_taylors 2014; TripWowjesseterleri 2014), as in Fig. 3.

33 Tourism involves “the management of absences, making them stay absent, or making them manifest” (Bærenholdt 2012: 117). Considering relational definitions of indigenous identity that highlight the importance of social context (de la Cadena and Starn 2007; Maybury-Lewis 1997; Merlan 2009), in these cases the absence of modern items or situations emphasizes, or even creates, indigeneity for tourist display. Caton and Almeida Santos have found the same patterns in the photographs taken by overseas students. They write that, while we can certainly expect travellers to focus their attention on what is different and exotic, it is “the frequency with which these images occur, and the concomitant lack of photographs depicting modern cultural practices and achievements, that constitutes a pattern of dichotomous representation of tourists and Others” (2008: 18).

34 It is also noticeable in my sample that the notions of timelessness and tradition are linked particularly to women. Weismantel has pointed out that, a cross the Andes, postcards sold to tourists offer racialized images of indigenous culture: market women appear in traditional handwoven dress, surrounded by flowers, vegetables, and earthen pots, while common manufactured goods like batteries, blenders, and radios remain absent. She argues that these absences present a “fantasy of premodern life” that deepens the gap between the usually White viewers and the depicted locals (2001: 180). This reflects common trends found in tourist postcards from other locations: Native Americans (Albers and James 1988), as well as indigenous peoples from Africa and Australia (Edwards 1996, 1997), are typically depicted wearing traditional clothes and engaged in activities typical of the past, thereby providing the image of a pure and authentic local. Fabian has criticized anthropology’s practice of describing other people as living in the past, thereby conflating time and space and denying others coevalness with the anthropologist (1979). Sometimes “the others” are presented in positive terms as close to nature and following timeless tradition, or they may be presented more negatively as being at a lower stage of development. In both cases they are situated in, and naturalized as, part of the past and thereby separated from the viewer, whether anthropologist or tourist. This discourse seems to be enacted in tourists’ photography in Cusco as well. The common practice of excluding other tourists from photos also dovetails with this approach, since their presence destroys the image of travel, not just to a different place, but to the past.

35 Other ways of distancing become evident as well. Pruitt and LaFont describe the romanticizing gaze of American tourists in the Caribbean. While middle-class people tend to stay away from poorer areas in their home towns, as tourists they often seek out the shacks on a Caribbean beach, and find them quaint and appealing (2004). Poverty and real struggles become subsumed in the romanticizing gaze. Labelling photos of indigenous people in Cusco “Picture book” shows that similar views are enacted here. Conversely, the title “Rest Time from Hassling Tourists” indicates a lack of understanding and negative judgement of people and the challenges they face (TripWow-themurphys 2014).

36 Tourist networks are performed through the interactions of people, objects, and places (van der Duim 2005: 972), and photography can fix these enactments into a more permanent form. A semiotic approach emphasizes the similar meanings of analogue and digital imagery (Larsen 2008: 144), while ANT highlights the different affordances of the digital network. These technologies now allow for much faster production and distribution of images, so that the explicit and implicit messages can be shared with a wider audience and thus have a greater impact (Larsen 2008; Molz 2004, 2006; Scifo 2005; Stepchenkova and Zhan 2013).

37 Corporeal and virtual travel are intertwined and mutually constitutive (Larsen 2008; Molz 2004). Online user-generated images have the potential to complement or challenge prominent narratives. In their comparison of tourist marketing images with those generated by travellers in Peru, Stepchenkova and Zhan found a greater presentation of local people’s everyday activities in the tourists’ photographs (2013). However, often older discourses are perpetuated through the digital network. As the results of this study indicate, tourists’ photographs serve primarily to enact travellers’ relationship to place, self, and to each other, rather than a focus on or connection with local people. Bærenholdt at al. even claim that “places are not only or even primarily visited for their immanent attributes but also and more centrally to be woven into the webs of stories and narratives that people produce when they sustain and construct their social identities” (2004: 10). Even photos without any people can serve to construct and enact personal identity, particularly considering that the photos are shared with others as an official presentation of one’s travel experience, and thus as part of one’s identity. Where indigenous people are pictured they appear mostly in staged situations, more as a colourful part of the environment than as actual people to be interacted with. Online travel images always have “fluid meanings and boundaries,” so that interpretations can vary based on individual, situational, and temporal factors (Molz 2004: 171). However, based on this limited analysis, the photographs largely follow the hermeneutic circle and perpetuate colonial discourses and essentialized views of indigenous people.

ANT’s Limitations and Possibilities

38 As we have seen, actor-network theory directs our focus to the underlying processes in the network. In a recent edited volume on ANT in tourism, the authors argue that ANT’s “main focus is not the usual why questions of social sciences, but rather questions of how social arrangements are held together” (Ren et al. 2012: 4). ANT directs us “to ask not what tourism means but what it does” (Franklin 2004: 297), or, in similar words, “to ponder not what tourism is, but rather how tourism works” (Ren et al. 2012: 13). ANT “does not offer wide ranging explanations of the world” but rather seeks to provide “examples, cases, and stories of how things work, of how relations and practices are ordered” (5). Latour himself has described ANT as more of a method than a theory (2005: 27). Considering that ANT strives to overcome conceptual dichotomies in its approach, it is surprising to see this dualistic distinction between how and why.

39 I think we are better positioned to explain how things work by also paying attention to the underlying reasons and to explanations given by human actors in the network. For example, elsewhere, tourists have reported that maintaining connections with friends and family at home motivated them to take photos of themselves and share them online (Molz 2004; Scifo 2005). The hermeneutic circle whereby tourists reproduce images similar to those viewed before (Albers and James 1988; Urry 1990) can provide further explanations for this behaviour.

40 Another issue is the consideration of temporality. According to ANT, “we cannot take anything as a given, as everything is an effect of relational practices” (Ren et al. 2012: 5). While I agree that “power, intentions and interests are relational effects, not resources to be possessed or exerted” (17), I do believe there are cumulative effects. If power, intentions, and interests are the outcome of relationships, will not past relationships have produced—not as permanently existing entities—effects that carry on in some form? Like Caton and Almeida Santos, I have identified “discursive strategies of essentialization and exoticization” (2008: 22) in my sample. Local people are almost entirely represented by those with clear indigenous markers, even though this is not representative of the actual population in the region.

41 Tracing these patterns to colonial discourses, past processes in the network can give us a fuller understanding of the current enactments we observe. In studies of a Polish tourist town (Ren 2010a, 2010b), an Icelandic community preparing for tourism (Jóhannesson 2005), and the cachet of Cuban cigars (Simoni 2012), the various authors of the studies do, in fact, consider some of the previously established relationships and themes. Simoni, for example, describes how images of elderly Cubans smoking cigars have become iconic over time and are promoted in tourist brochures and postcards; old people are now enacting and staging this role by posing for tourists to make money (2012: 64). I think it is important to strive for a balance between approaching themes, distinctions, and characteristics as continuously constructed and performed, and also acknowledging the impact of previous or other networks. By seeing them too exclusively as effects and not as causes, we are prone to miss important parts of the picture.

42 The above issues could be investigated more thoroughly using an ethnographic approach, as ANT proponents suggest (Jóhannesson 2005; Latour 2005; Ren et al. 2012). Larsen argues that most research on photography has focused too narrowly on the images, while neglecting “the embodied social practices or performances” of taking photographs (2008: 143). Observing tourists’ practice of taking pictures, and the interactions around that practice, would provide a better understanding of the (possible) processes of staging, while interviews could shed more light on travellers’ own perspectives. Also, both people and objects could be traced much further in the network. For example, examining which of the indigenous markers, such as animals and hand-woven clothing, people pose with would lead to a deeper understanding of local culture and tourist displays. Likewise, prominent absences (of, say, modern items or situations) could be investigated in more detail. By participating in common tourist activities, a researcher can observe which situations and sites tourists tend to photograph and which ones they leave out of the record. In this study, I have primarily approached the photos as an ordering process that makes part of the tourist experience more stable and durable. This happens the moment a photo is taken, and, more so, when the photo is viewed later and becomes a tool for remembering the experience (Bærenholdt et al. 2004; Scarles 2008), as well as when it is shared and affects the views and expectations of others who have not (yet) visited this place. Since ANT emphasizes the interactions of different actors through the network, an ethnographic approach is ideal for exploring these complex dynamics in detail.

Conclusion

43 The analysis of 146 tourists’ photographs posted online has revealed some interesting trends. The images focus strongly on architectural features in and around Cusco. People appear in fewer than half of the sample photos, and those that are included are mostly tourists, followed by local people showing clear indigenous markers. By taking pictures that downplay or hide the presence of other tourists, travellers may partially enact the adventure discourse of the brave explorer. Interestingly, however, the vast majority of photos reflect the main tourist sites only; the romanticizing adventurer’s gaze stays largely on the beaten track.

44 Sontag has written that “to photograph is to appropriate the thing photographed. It means putting oneself into a certain relation to the world that feels like knowledge—and therefore like power” (1977: 4). Tourists can exercise power by fixing their gaze in photographs and thus strengthening a certain ordering in the tourism network. By creating and distributing images of indigenous people appearing predominantly outside, in traditional clothes, and accompanied by animals, tourists actively perform difference between themselves and the people pictured. Locals become distanced from the viewer, not just as inhabitants of a different space but of a different time. An ANT approach emphasizes how photographs do not simply record or reflect difference, but actively create it. This study indicates that the essentialization and exoticization reported from travel images elsewhere are prominent in photos from the Cusco area as well. Yet we also must be careful not to assume a victim role for indigenous people. Research elsewhere has shown that local people consciously choose what to display and what to hide from tourists (Bruner 2004; Maoz 2006).

45 The interpretations I offer here are based on only partial consideration of the material and are thus meant as a starting point rather than a full analysis. I have only considered the photos in terms of broad categories and general motifs, yet there are many other aspects of the pictures that could be analyzed further. For example, for most of the sample, the image and/or the description make clear where the photo was taken, so places could be mapped to present a visual overview of photo locations, both for individual slide shows and for the sample as a whole. While I considered the prominent motifs in the image, I did not address aspects like camera angles, composition, different objects, or the posturing of people pictured. In contrast to the indigenous people, tourists often assume more dramatic poses in their photos, taking up more space or pointing to specific features in the environment (see Fig. 2).

46 In addition, the TripWow website (2014) constitutes its own network and materiality, with features that frame the photos through a specific ordering. The site announces that its “‘Indiana Jones’-style animated maps are both fun and informative” (TripWow 2014). These maps indicate the general location of cities but lack other detail; in addition, this framing clearly evokes the traditional masculine adventure discourse in which the tourists are expected to situate their photos and experiences. Thus, both the content and materiality of the particular photographs, and the website as a whole, offer further possibilities for analysis.

47 The tourist destination is performed by many different actors with different backgrounds and motivations. While this study only examined a small section of the tourism network, an ANT-based approach of tourism is best conducted through ethnographic fieldwork. While photographs form an important aspect of the tourist experience, we cannot know to what degree they represent the travellers’ actual perspectives and views (Caton and Almeida Santos 2008: 23); ethnographic work makes it possible to explore these possible discrepancies more fully. ANT’s greatest contribution is that it does not consider social structures a given but rather seeks to examine how these are continuously constructed and enacted (Latour 2005; Ren et al. 2012). However, I have argued for the importance of acknowledging the results of previous constructions from other networks. While I agree that social structures do not exist outside of relationships and interactions, actors are always part of different networks, and so the effects of an ordering in one network can become the causes of ordering in another. Jóhannsen et al. write that a recent development of ANT is a greater emphasis on multiplicity or the insight “that many different networks exist and enact multiple versions of tourism destinations or objects” (2012: 167). While maintaining its emphasis on active construction, ANT’s greater recognition of multiple networks and their interaction may prove fruitful for achieving a more balanced view. Photography can be considered one of tourism’s defining aspects, and ANT provides a useful tool for understanding this practice, not just as a recording of the gaze, but as the active construction of power relations, and individual and social identities.