Articles

Early Christian Perceptions of Sacred Spaces

Abstract

Previous studies of early Christian beliefs have portrayed the community as being highly anti-materialist and anti-social. It was argued that Christians rejected the category of “sacred space” and exhibited only secular and functional behavior regarding place. Beginning in the late 1970s a growing body of scientific literature has questioned the veracity of these claims. Reviewing the material culture record in the first four centuries of the Christian community (architecture, objects, art), this article proposes that Christians were far more culturally homogeneous in late antiquity, and accepted in large part the material mediation of the divine.

Résumé

De précédentes études au sujet des croyances des premiers chrétiens ont brossé le portrait d’une communauté hautement antimatérialiste et antisociale. Elles soutenaient que les chrétiens rejetaient la catégorie « d’espace sacré » pour ne retenir que les aspects séculiers et fonctionnels de l’espace. À partir de la fin des années 1970, un ensemble grandissant de littérature scientifique a remis en question la véracité de ces affirmations. En faisant l’examen de la culture matérielle des quatre premiers siècles d’existence de la communauté chrétienne (architecture, objets, arts), cet article émet l’hypothèse que les chrétiens de l’Antiquité tardive avaient une culture bien plus homogène et qu’ils ont accepté en grande partie l’expérience matérielle de la médiation avec le divin.

1 The study of material cultures of various groups can add significant clarity to academic characterizations of historical attitudes and beliefs. When considering the whole array of material objects and their use, a more complete view of a community may be made beyond the limitations of textual histories. This is certainly true of Christianity, though not often clearly represented. The believing community not only has a history of texts, especially sacred scriptures, but a material history as well. To this extent, understanding the significance of early Christian artifacts can call previous conclusions regarding Christian self-identity into question and offer new perspectives regarding Christian belief. One possible area for revision offered by the methods of material culture concerns early Christian attitudes toward “sacred space,” the term made so familiar by the phenomenology of religion. In its most general sense, sacred space indicates the spatial mediation of religious experience. This is to say, religious experience is embodied in the physical makeup of the everyday through which the encounter with the divine is facilitated. Sacred space almost always indicates ambiguous boundaries and definitions of both sacrality and spatiality that make up the religious experience of a group or society. Material culture assists in deciphering the relationship between place and encounter with the divine by evidencing the physical traces of a particular community’s life in a given spatial context, allowing for the analysis of behavioural patterns and cognitive remnants that witness to a history of belief.1

2 In light of these considerations, this essay argues that theories prevalent in the mid 20th century, claiming early Christians radically rejected the spatial mediation of religious experience and stood apart from their broader cultural milieu, appear highly uncritical, if not all together erroneous, when viewed through the lens of material culture.2 The architecture, material artifacts, art, and writings of Christians, when considered in tandem, show the community acted in ambiguous manners toward spatial categories of sacrality in their material interactions. I suggest that early Christian tradition accepted the notion of sacred space, the spatial mediation of religious experience, or at the least was not closed to the idea. The adoption and adaptation of the temple theme in texts and buildings by the community ultimately confirms this trajectory. Scholarship of the past century has at times denied this broader perspective as indicative of Christian spatial priorities.3 The pluriformity and advances within material culture studies suggest fresh consideration of the topic is desirable.

A Problematic Thesis: Deichmann’s Topophobic Christians

3 The work of Friedrich Wilhelm Deichmann (1909-1993) is the most prominent of theories claiming to find, in the first four centuries of Christianity, an absolute and definitive desacralization of place. In his view, an early purist Christian self-conception was betrayed only under the corrupting influence of Constantine’s imperial patronage (Deichmann, vol. 1: 52-59). Christians, like their Jewish antecedent, he argues, eschewed places of spatialized divinity and the sacralization of place altogether; Jews did so because of the development of the synagogue system after Titus’s destruction of the Jerusalem Second Temple in 70 CE. No longer having the Jerusalem Temple, it was easier to find new religious meaning regarding God’s physical presence by abandoning the concept of spatialized divinity. Christians avoided the concept because of Pauline Christology and Johannine Temple-Christology. The writings of these two New Testament authors, suggested Deichmann, showed that, for Christians, the mediation of religious experience was found either in the community of believers or the person of Jesus and not in any particular place. The two faiths, almost simultaneously adopted a functional, non-spiritual, stance towards places of communal gathering and worship. As evidencefor this supposed negative Christian disposition toward sacred space, Deichmann points to the lack of architectural information regarding the place of the Christian cult preceding the Roman emperor Constantine. He interprets the lacuna in the architectural record to be indicative of a conscious choice against sacred space and a choice for the supposed functional and secular setting of the house-church (domus ecclesiae) or public dining hall. Sharing this conclusion, Harold Turner similarly characterizes the architectural situation of the same period thus:

4 In short, Christians exhibited topophobic behaviour indicative of their theological belief: space did not have a sacral character and they avoided material interactions which would indicate the contrary.

5 But attempts by previous scholars to deduce Christian attitudes toward sacred space, assumed to be accurate descriptions of a generalized religious experience, as represented in Turner’s absolute judgment just cited, have limited value. As Paul Corby Finney has pointed out, the interpretation of textual evidence, together with the paucity of an early architectural corpus, thought to be indicative of an anti-sacral designation of space, is problematic (Finney 1988: 319-339). Finney judges the studies of Deichmann and Turner to be “distorted and quasi-historical” (1988: 337). Several issues regarding the textual and architectural evidence so crucial to a correct interpretation of Christian attitudes are glossed over or left unresolved.

6 Firstly, texts of various genres (scriptural, liturgical, patristic) and periods (mid 1st to early 5th centuries) are read as one thereby creating a false textual history and generalizing the factors that gave rise to a specific text (Quellenforschung). As relates to Pauline and Johannine biblical texts, it is never recognized that their canonical status is evolving parallel to the development of the Christian community; Deichmann and others assume the texts have a globally normative meaning and status they were not likely to enjoy in diverse Christian communities. Moreover, the conceptual content of the texts themselves are not usually thoroughly investigated, especially regarding Jesus in relationship to the Jerusalem Temple. The scholars do not ask, for example, if the Pauline and Johannine texts are speaking of the relationship of Jesus to the Jerusalem temple solely as a manner of establishing the status of Jesus for the nascent Christian community, or if the biblical authors intended to negate spatiality in the experience of the sacred as such.

7 Secondly, the architectural record is presented in a problematic manner. It is inadequately portrayed as an argument from silence thought to affirm an anti-spatial attitude. As will be indicated below, the architectural record is not in fact so silent. Also problematic is the limitation of understanding sacral space solely in terms of direct theophanic presences, as was believed to be the case with the Jerusalem Temple, but also of Roman temples and other shrines of the period. The sacral designation of the Jerusalem Temple is then tied to an architecturally formalist rejection of later Christian architecture. This is to say, because it is assumed a priori that the sacral associations tied to the Jerusalem temple where purposefully rejected by Christians worshiping in homes, later monumental and formalized architecture of the church, such as the hall-church and basilican-church, are rejected as aberrations and inauthentic expressions of religious experience. Official sacral designations of places, Deichmann argues, erroneously emerge again through a corrupted Christian theology of space brought about by the imposed imperial use of the Constantinian basilica. Just as Christianity rejected the monumental Jerusalem Temple, the formalized architecture of the basilican-church must also be rejected as antithetical to a hypothesized Urchristentum. True Christianity, such logic asserts, dwelt in the domestic setting of the house-church. In short, what does not exist in the early architectural record is assumed and what later architecture that does exist is rejected.

8 The discrepancies and mischaracterizations in Deichmann and Turners’ analysis of the textual and architectural sources pointed out by Finney distinguish quite clearly the possible deficiencies and pitfalls in the interpretation of early Christianity attitudes toward sacred space. In response to these limitations, a significant methodological shift away from those espoused by Deichmann is necessary. Any portrayal of Christian attitudes toward the category of sacred space cannot be derived solely from a Quellenforschung or the views it is supposed to absolutize.4 Nor can the architectural record be adequately understood simply by purely formal means—identifying architectural structures according to form outside of contemporaneous use and cultural contexts. The French historian of ancient Christianity, Charles Pietri (1932-1991) noted that the attitude toward the sacred sought out in early Christianity, on display primarily in worship and cultic spaces, is a phenomenon of culture and society. This is to say, that the accurate portrayal of early Christianity emerges in relief out of the contemporaneous social environment in which believers found themselves (Pietri 1997: 237).5 Scholarly inquiry regarding Christian notions of sacred space must understand the concept in view of a larger Christian material culture and the broader social and cultural milieu.6

9 As such, within studies relating to sacred space and particularly to the place of Christian worship a few developments are especially notable in reshaping the evidence.

Reassessing the Evidence: Christian Architecture—A Cultural Dynamic

10 A substantial shift in understanding Christian attitudes toward sacred space came about with Michael White’s The Social Origins of Christian Architecture (1990), which built upon the sociological orientation of Pietri and investigated architectural features of cultic spaces in late antiquity with greater precision. The study is significant for its clear establishment of the historical factors that contributed to the development of early Christian architecture, including social composition, the wealth of Christians, both private and communal, as well as liturgical developments. Debussing any credibility from the assertion that Christians chose not to have identifiable particularized spaces argued for in earlier theories (and hence anti-sacral), White shows that the evolution of Christian architecture follows the same patterns of development of other cultic spaces in the late antique Mediterranean zone. The Social Origins of Christian Architecture explains that the extant corpus of early Christian architecture, and epi-graphical and literary evidence, reveals a pattern of building that relied upon patronage in accord with the material and financial capabilities of the community. No alternative theory for the scant architectural record is provided, other than thatChristians chose not to build specific sites for Christian worship; the lack of distinct Christian spaces in the 1st-3rd centuries is not evidence of an anti-spatial conception of the divine but is typical of the cultic building patterns of Jews, Mithras, and other cults not sponsored by the Roman Empire. That is to say, Christians built as they were able to obtain real property and had the financial capacity to see to its upkeep. In fact, their building patterns coincided with religious groups that held spatial-sacral beliefs, thereby negating, or at least leaving open for further investigation, Deichmann’s assertion of a topophobic Christian community. It is questionable that had a community been so inclined against spatial-sacral categories why their practices would not have been somehow divergent with other cultic groups which did espouse such beliefs.

11 Essential to redefining the view that Christians did not accept the sacral nature of religious space is the only more recent recognition that ancient Mediterranean culture had no sense of secular space; private and public, yes, but even the home and dining hall was a religious locale (Hurtado 2010; Smith 2003: 67-74). In fact, Michael White shows that Christians chose to modify or build locations specifically given over to cultic activity prior to Constantine’s toleration (1990: 129-31). True, this fact alone does not definitively indicate how the space was interpreted by Christians, but it does evidence the propensity to separate out from the urban fabric of the insular block particular locations of religious significance and refrain from indistinct architectural existence in the home or public dining hall. Implicit in such behavior is the phenomenological habituation to separate out from the broader life-world, seen by the community to be neutral or a competitor, particular locations of religious significance where their divine was encountered.7

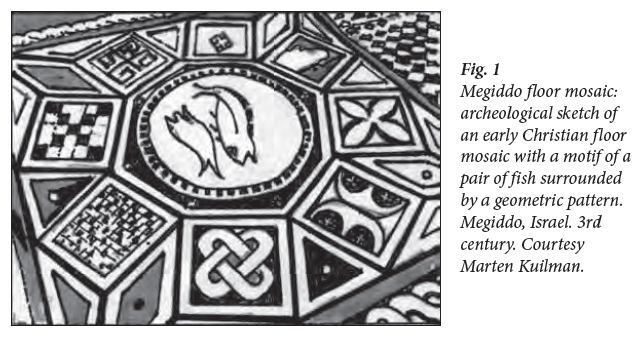

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 112 In terms of the Christian architectural record, it cannot be avoided that the earliest clearly culticspace discovered to date, the Megiddo church, is a large 54-square-metre formalized space dating well before Constantine, to ca. 230 CE. Like other cultic spaces of the time it contains an elaborate mosaic floor, including the early and iconic symbol of the fish (Fig. 1). Most tellingly of Christian attitudes of the time, are the three inscriptions on the floor. All three are typical of Roman ex voto offerings found in temples, imperial basilicas, and funerary spaces asking that the reader remember the donor in prayer. The most significant of the inscriptions is for a table (τράπεζα) at which the Christians celebrated the Eucharist. Whether it was a wooden/portable or stone/fixed altar is not clear.8 In any case, the table-altar receives a dedicatory inscription itself in the same manner as the majority of altars did within the Roman Empire in the late antique period. It is doubtful that Christians employing typical pre-existing religious devices according to established patterns of sacred space were at the same moment rejecting sacral-spatial designations involving the divine. In fact, the dedicatory inscription in traditional Roman religion recalled the elevation of a space to a sacred, inviolable status.

13 Contemporary research also indicates that the formalization and monumentalization of these spaces, as seen at Megiddo, happened more quickly than previously acknowledged. For his part, White suggests the necessity of viewing the architectural record as an evolutionary process from house-church to hall-church to basilica that happened in an organic, even if uneven, fashion. Contrary to Deichmann’s assertion that the basilica was an imposition of an architectural form that attached sacral categories foreign to Christians, the scholar Silvia Siena has recently shown that that cathedral and episcopal complex at Milan, Italy, was already in development before 313 CE (2012: 29). These monumentalized structures probably made Christians stand out in the cityscape, prompting later persecutions within the Roman Empire—in as much as a minority group had to be in the ascendancy to be viewed in suspicion or to be officially recognized as an inevitable moral, economic, and spatial reality that had to be accepted or integrated. Hence, the Christian architectural trend was already moving toward formal and monumental spaces well before the Peace of Constantine and his lavish donations to the Christian community. The level of acceptance of sacral categories this might show within monumental architecture is more likely an authentic expression of the social group rather than the corrupting influence of imperial patronage. Bolstering the architectural corpus can be added consideration of other evidence established in the broader view of Christian material culture.

Reassessing the Evidence: Christian Objects—A Becoming Christianity

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2 Display large image of Figure 3

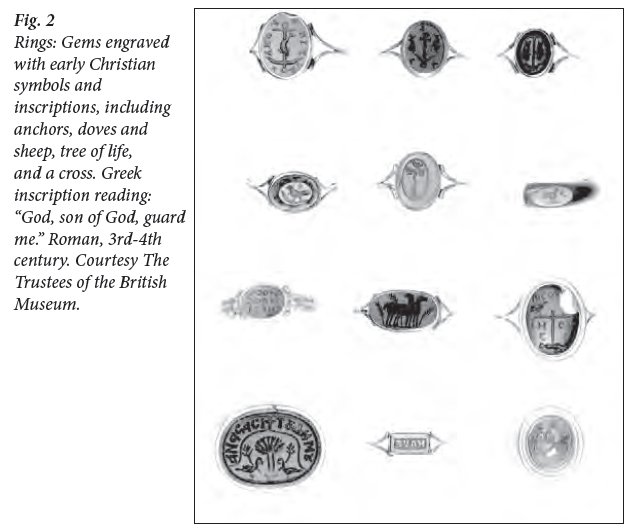

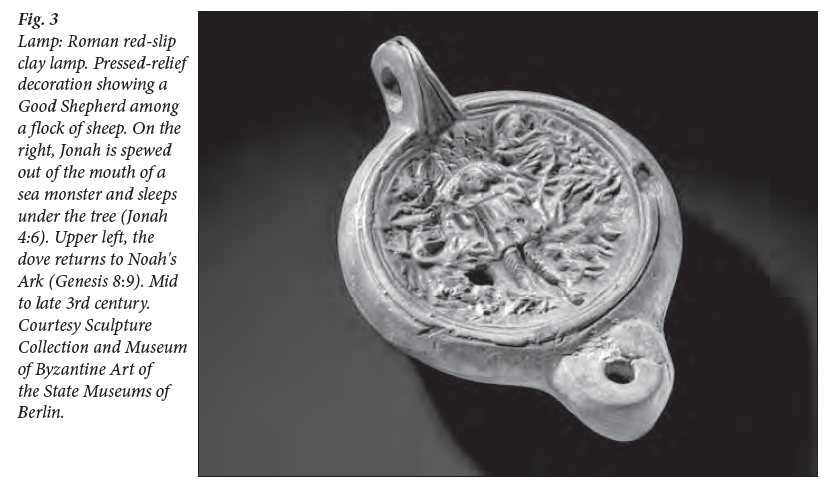

Display large image of Figure 314 While it is often proffered that early Christians were aniconic, iconophobic, and topophobic, extant traces of material culture suggest a different view. In 1977 Mary Charles Murray presented to the Pontifical Institute for Christian Archeology a robust minority judgment of the historical data concerning the period of ante-Constantinian Christianity. She suggested that the dominant historical-theoretical framework giving rise to a view of early Christians as a radically utopian, spiritualized, anti-social community was not verifiable in the material record, and, in fact, that the opposite was more likely the truer state of affairs (Murray 1977, 1981). One of the many notable aspects of her work was the elucidation of the breadth of material objects evidenced in Christian writings of the first three centuries of the Common Era, including clothing, signet rings, and utilitarian objects (Fig. 2). The literary evidence suggests that Christians readily took up religiously distinct items in similar manner to other cult groups. For example, Clement of Alexandria discusses the boundaries of images appropriate to signet rings of Christian women and men (1867, vol. 1: 316-17). These and other material objects suggest a far greater homogeneity between pre-Constantinian Christians and their social surrounds. That archeological and literary sources offer an array of identifiably Christian items of a personal and cultic nature suggests that while some particular Christian writers had reservations regarding the status of material objects, the everyday Christian was far less inclined to introspection in this sense. The adoption and adaptation of religious precedent is seen as well in such things as household lamps. One considers the historical juxtaposition to be made between the highly eroticized cultic-domestic lamps of Pompeii and cultic-domestic lamps bearing Christian symbols such as the Good Shepherd, the rooster, and the Christian banquet symbols of bread and grape (Fig. 3). While invoking different Mediterranean religious traditions, both are invoking religious symbolism nonetheless. As Finney suggested, the appearance of plastic expressions of belief, such as the decoration of Christian lamps, was the result of a progressive evolution of religious instinct and the conscious strategy of Christians to take on a visible role in their social context (Finney 1997: 101, 290-91). At the same time, taking on a visible role was not simply an economic or social eventuality but was based in religious believing itself. Christians who in their material existence copied pagan behaviour to an extent would not be rejecting the material mediation of religious experience. So, for example, the talismanic, apotraic, or fetishistic properties the Greco-Roman tradition saw in personal items were likely believed by Christians to be present in their objects as well. Clear examples include Old Coptic textual amulets and Christians who in life sought out protective power from the bodies and belongings of martyrs, and who in death desired to be buried in close proximity to the martyr as a guarantee of salvation (Meyer and Smith 1994: 20; Skemer 2006: 23-44; Yasin 2009: 26-49). If the use of domestic objects characterized belief in supra-natural properties it would suggest that cultic spaces were even more capable of the material mediation of religious experience; and again, that Christians in taking up pre-existing religious attitudes evidenced in minor objects would also likely share similar views regarding the sacral status of cultic places as their social counterparts. But even more significant than domestic objects for determining this outlook is the material development of Christian cultic life, including codices of sacred scriptures and liturgical utensils like Eucharistic cups. In these objects, positive attitudes toward ritual behaviour are on display.

Display large image of Figure 4

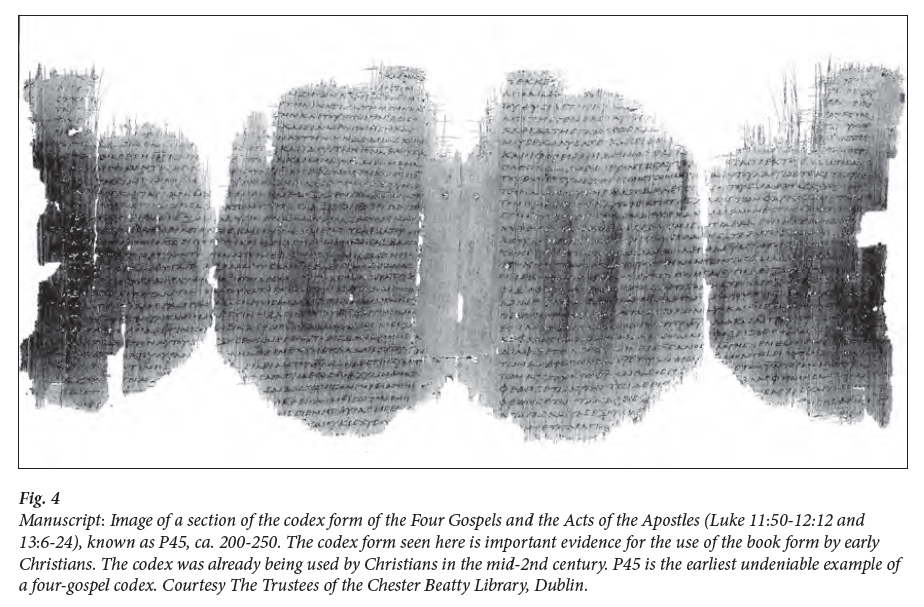

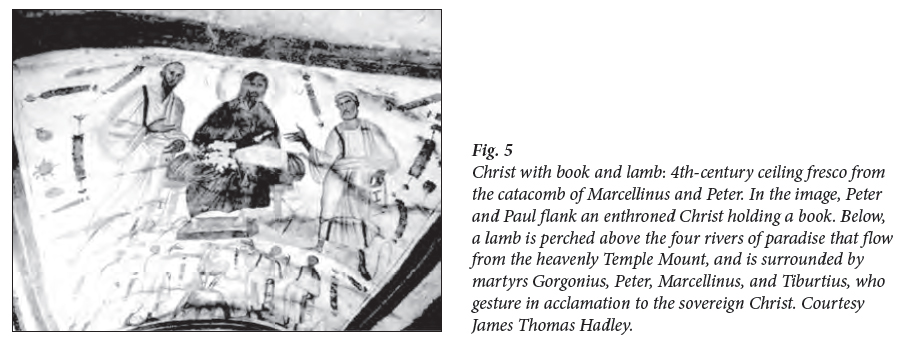

Display large image of Figure 415 Larry Hurtado argues that the earliest material Christian artifacts are, in fact, biblical manuscripts, though they are rarely treated as “objects,” and consequently a wealth of information regarding early Christian material culture is overlooked. These Christian codices represent a particular form of material culture unique to Christian communities in the physical form of the texts themselves. Codices embody a broad attempt from the mid-2nd to 3rd century to place Christian scriptures in “book” form rather than rolls, possibly motivated by stylistic, symbolic, and practical reasons (Hurtado 2006: 61-83). The book form perhaps reflected the original state of the Pauline epistles bound together, or an attempt to visually distinguish Christian texts from the writings of other religious groups that utilized a roll (Fig. 4). Regardless the cause, the book shape came to represent the Christian kerygma (originating apostolic preaching) in material form. The presence of a book in the midst of the community was so formational, Christians quickly identified themselves as people of the Book of Books (Jeffrey 1996: xii-ix). Certainly the book form must have impacted the believer’s perception of the physical cultic location where both the ritual reading of the scriptural text and its shape indicated the presence of the Christian’s god continuing activity on their behalf. The community likely perceived that in as much as there was a particular and appropriate place of the Christian ritual meal (Eucharist) so too for the Christian book and its public reading. The formalized altar, transformed from wooden to stone table, probably saw the concomitant development of formal books in the 3rd century. Hence the book and the altar emerged as physical presences, which established a ritual center and invested it with sacrality. In other words, the surrounding space “absorbed” the sacral character of the book. Evidence of this rapport becomes apparent in the appearance of representations of books in Christian art within funerary contexts, baptisteries, and churches. In the earliest Paleo-Christian art, rolls are often depicted but the symbolic intention is likely the same. Almost immediately upon the appearance of Christian art, rolls are replaced with books. This transformation and formalization of book of scriptures can be seen in the early Christian image of traditio legis; Christ handing a scroll will change into an image of Christ holding a book (Fig. 5). Moreover, standalone images of books representing the four gospels become commonplace, often portrayed as standing on altars or, later, placed upon a throne. In these images, the book has the power to rule and to judge. The point to be made is that the image was a referent to the sacral character of actual books. Encapsulated in the actual book emanated the saving mysteries that transcended the internal texts by which God’s actions in the world were continuing to unfold. From the earliest Christian period, identity was inexorably bound up with the book and its reading levelled a formative claim upon the community personally and shaped patterns of worship (Stewart-Sykes 2006: 116-17). Because of its fundamental importance, Christians felt compelled to ritualize its shape, use, and depiction.

Display large image of Figure 5

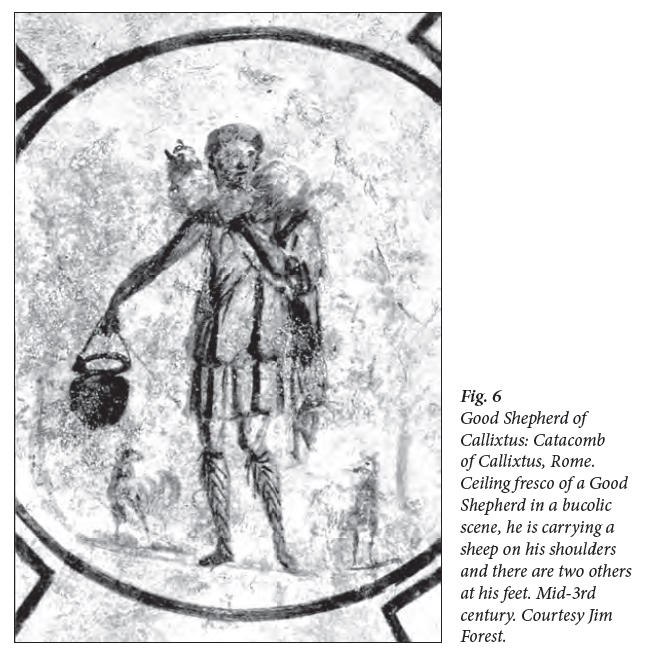

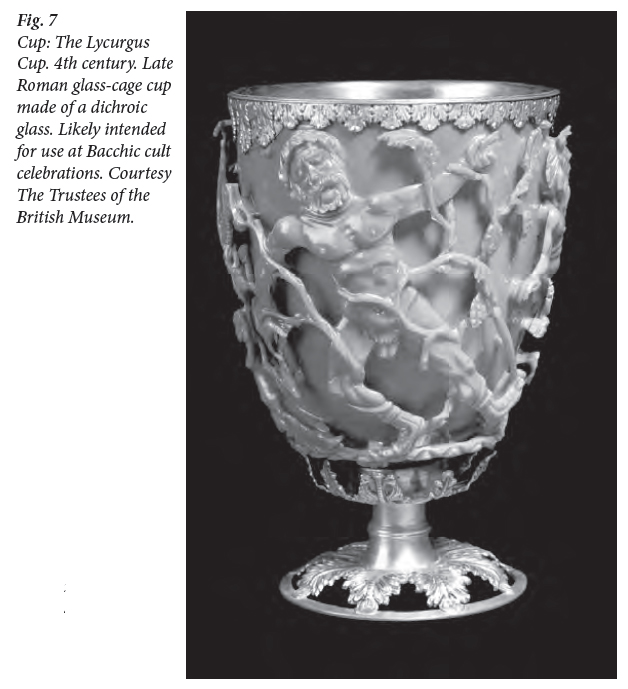

Display large image of Figure 516 Also significant in the material culture of the time is the cup of the Christian Eucharist. Already at the outset of the 2nd century, Tertullian’s De Pudicitia mentions Eucharistic cups bearing the image of the Pastor bonus, as did terra-cotta lamps of the time (1954b, vol. 2: 1301). De Pudicitia is an initial indication of a formalized ritual life, that on the level of materiality, is little distinguishable from the use of cultic cups and ritual dining found throughout the Mediterranean. While a particular group might interpret its actions or beliefs in divergent ways, one can say that at the level of materiality and ritual such religious life is not dramatically divergent from the larger cultural context (Scheid 2007: 270; Klinghardt 2012: 11-12). Ritual cups in late-antique ritual dining were distinguishable from daily items by design and decoration (Fig. 6). The cups were often identified by images of the deity, in whose worship they were utilized (Vikan 1995: 13). Identifiable cult objects, like the cup with the image of the Pastor Bonus referred to by Tertullian, illustrate that Christians also exhibited a type of religious experience that separated out and reserved particular objects as more appropriate for ritual acts. Christian communities of the time thought to distinguish between daily and religiously meaningful objects, thereby exhibiting belief in the material mediation of religious experience. Such identification was gradual, not because of belief to the contrary, but because of the socio-economic capacity and societal context of the community. Finney explains that, from the late 1st century, Christian material culture expanded through stability and acquisition of real property to the extent that it was possible to express a public identity and engage more robustly in material culture, since material cultural, being a visible and therefore public reality, always requires permanency and resources (1997: 108-10). It is not surprising therefore, given this expansion, that about a century after De Pudicitia, the Gesta apud Zenophilum records the confiscation of numerous liturgical objects at Numidia, North Africa, in 303 CE during the Diocletian persecution: “two golden cups, six silver cups, six silver jugs, a silver casket, seven silver lamps and eleven bronze lamps with chains” (MacMullen 1992: 249).

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 617 This burgeoning material culture of small cult items, exemplified, for example, in the Leuven Database of Ancient Books that shows the 2nd and 3rd century as producing by far the most copies of scriptural texts (Hurtado 2006: 45), finds correlation with White’s study of ante-Constantinian Christian architecture. The numerical increase of known cult objects in the historical record is paralleled by an increase in renovated properties solely serving Christian worship and the accrual of property for catacombs. This is the period of the renovated domus ecclesiae, as at Megiddo and Dura-Europas, and the somewhat later form of the aula ecclesiae (White 1990: 118ff). That a growing body of cult objects occurs in concert with a growing number of house-church properties indicates the formalization of attitudes regarding the spaces of Christian worship. The increase evidences the transcending of functional considerations of objects and space in favour of formalized relationships to materiality and spatiality in the mediation of religious experience. Concurring with this view, White concludes that, “Ritual forms then came to replace the casual elements of house-church dining, though [Christians] attempted to preserve it through symbolism,” including the architectural structure itself (120). In such circumstances the putative role played by anti-materiality or topophobia in the community, grounded in Urchristentum, is doubtful; so too, then, the broad assertion that Christians did not conceive of sacred space as such. If the cultural assertion remains, regarding the formative relationship between actual place and religious experience and its cognitive impressions, one is not surprised to find in the above-mentioned historical data of the Christian community a more open and malleable attitude concerning cultic practices and, therefore, acceptance of pre-existing cultural patterns of religiosity, even if at a pre-reflective level. This remains a probable condition for the shape of early Christianity and is expressed by what both Finney and White term the adaptability or adaptive environments of early Christians (White 1992: 25; Finney 1997: 109).9

Reassessing the Evidence: Christian Art—Claiming Space

18 Assessing the early Christian attitude toward sacred space also requires consideration of religious art. As an expressive indicator, art—especially in its ritual context—provides a particular view of a group’s belief system and self-understanding regarding materiality and spatiality. A hallmark of development in Christian material culture in the middle of the 3rd century is the adornment of religious settings with room art executed in fresco and mosaics. The appearance of this early Christian art evidences three characteristics: adaptations of overtly pagan themes to those Christian, traditional decorative themes interpreted by Christians as symbolic of their faith, and biblical narrative works (Jensen 2000: 10; Snyder 2003: 68, 89; Bisconti 2000: 13-17).

Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 719 The catacomb complex of Callixtus (ca. 190-218) is the first known example of Christian painted art and appeared at a time Roman Christians seem to have had a favourable relationship with the Emperors Elagabalus and Severus Alexander (Curran 2000: 36-37). Art in the catacomb formalized the setting and amplified its spatial qualities, not only by distinguishing architectural volumes with characteristic red and green outlines but by positioning images upon discreet architectural surfaces, such as ceilings and vaults above cubiculum. According to the phenomenologist Mikel Dufrenne, an image is an aesthetic object that creates a perceived event, whose purpose can only be completed in its perception by an expected viewer (1973: 218). The aesthetic object serves therefore as a liaison between space and time, which binds the viewer to the locale evoking emotion and enabling the communication of values. From this point of view, the choice of the Callixtus Christians to incorporate images into their burial spaces implied an official status and material relationship between a specific place and the community. Moreover, given the dynamic of the image as a seen object that created a space-event, it can be said that catacomb art represented the belief in religious experience that was mediated by location as the space took on an eventfulness in the watching of symbols and biblical images. Thus a two-fold insight is derived from the Callixtus catacomb: the willingness of Christians to demark particular, significant locations and a correlating factor that, at the time, any architectural instantiation of religious place (such as catacombs and house-churches) was expansive and inclusive enough to include new loci within the religious experience.10 Christian art seemingly played a significant role in stabilizing sacral perceptions in this expansion of Christian space. In the building of the Callixtus catacomb and the subsequent network of catacombs in Rome, the imaged space created a context in which the sacral nature of the space itself, the Christian dead, martyrs, biblical symbols of salvation, and the biblical promise of resurrection evoked a deeply felt character of the sacred (Bisconti 2013: 211-28). As to be expected, a primary image the viewer encountered in many of the hypogea was the image of Christ, either in the place of Hermes (the Good Shepherd), image of philanthropia (Fig. 7), or later, Christ surrounded by the apostles. No greater pictorial affirmation of the space could have been made.

Display large image of Figure 8

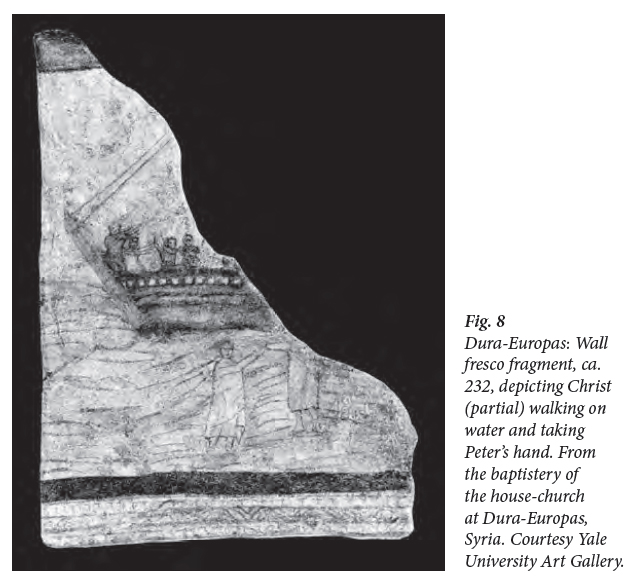

Display large image of Figure 820 The other earliest source of Christian painted room art is from the house-church at Dura-Europas (ca. 240), and represents the development of Christian attitudes toward sacred space at virtually the same moment as Roman catacomb art. The domus ecclesiae at Dura-Europas puts on display Christian belief both in the manner the building was modified and in the visual interpretation the space received through its substantial art program. The fresco program of the baptistery has been vigorously researched. Less commented upon is the act of art installation itself, which may say more regarding the sites fundamental importance for understanding Christian perception of sacred space than the theme of its images. At Dura-Europas there was again a conscious decision to create “imaged” space (Fig. 8). Here the larger cultural context is significant in identifying Christian attitudes. Likely the Christian act of utilizing images, as there is no evidence to the contrary, was understood as all use of images in the classical world were. Images created a reality before the viewer that was neither the thing imaged nor a mere material representation. What was constructed was a third reality, a “universe of representation, [...] a middle ground between animism and art” (Francis 2006: 210). The image created an active interchange between the viewer and the thing viewed, and thereby created a transformative reality.

21 Execution of the baptistery images at Dura-Europas indicates the community’s intention to create an effecting reality that involved the space and those who took part in ritual events. Viewing the baptistery images was not meant simply as a form of pedagogy representing Christian beliefs regarding baptism. Nor where the images simply signs or material representations of a dematerialized spiritual world. Rather, the image was intended to allow the viewer to partake in the induction of a number of effecting presences: The Good Shepherd, Adam and Eve, the Annunciation at the well, David and Goliath, the Healing of the Paralytic, Peter and Jesus walking on water, and the Bridesmaids of Matthew 25 (Serra 2006: 77-78). Consequently, the art was not intended to decorate but marked the house-church as a space empowered to mediate religious experience and divine action. The images lent to the space a talismanic-like property which had the capability of eliciting the reality the images intended to represent. That is to say, images of healing and salvation pervaded the space and imaged the salvific event that took place through the Christians’ initiatory rites. At Dura-Europas, the images should be considered then as what Fabrizio Bisconti has described as the movement in early Christian art toward the iconic; the actual mediated presence of the thing imaged through the gaze, which first becomes clear in the catacomb of Santa Tecla and then blossoms in Byzantine art (2013: 121, 303-10). The spatial precedent set by these examples of painted room art is clear. There is little reason to suggest that supposedly aniconic Christians, well before the Constantinian peace, would have supported the elaboration of catacombs or places of Christian worship with art if they were in fact hesitant to acknowledge or develop the idea that particular places had a sacral character.

Reassessing the Evidence: Spatial Realities of the Temple Theme

22 Completing the re-characterization of Christian attitudes regarding sacred space is the recognition that Deichmann’s depiction of the influence of Pauline and Johannine biblical texts as normalizing anti-material attitudes and de-locating the sacred in space is contrary to the overall trajectory of early Christian attitudes regarding sacred space. It is true that one sees in theapologetic tug of war of the 2nd and 3rd centuries an anxiety regarding temple themes evidenced by some Christian writers, like Marcus Minucius Felix (ca. 150-270 CE), Tertullian (ca. 160-225 CE), and Origin (185-254 CE), who declared that Christians had no temples and pagans had lifeless buildings (Felix 1982: 8; Tertullian 1954a, vol. 1: 148; Origen 1872, vol. 2: 508). However, these unnuanced polemical statements regarding temples are not matched in the historical record.

23 This is not to suggest that Christians before or in the era of Constantine constructed anything structurally akin to the temples of antiquity, with an outside altar and an interior cella, where the god in whose name the temple was dedicated was believed to be present via an image or token and served by a priestly group. Indeed, it is only in the mid-5th century that evidence appears of Christians beginning to architecturally appropriate pre-Christian temples for worship. Some scholars, though, have assumed a correlation between the apologetic rejection of temples and the adoption of the basilica-form church, believing the adoption of the basilica to be a rejection of the temple form, with its associated conceptualizations of material space and sacral presence. Articulating this proposition tended to be those in the German school of archeology working in Rome; first by Gutensohn and Knapp (1822), followed by Bunsen (1844), and repeated by Krautheimer (1986). In general, it was argued that the character of the basilica was public and secular. The characterization became so widespread the theologian J. G. Davies published a monograph in 1968 titled The Secular Use of Church Buildings. The characterization of both the “religious” temple and “secular” basilica requires further attention.

24 It must be considered that the accessibility of a temple was more indeterminate as they were meant to provide spectacle to patrons both outwardly and inwardly. Temple interiors were not wholly private spaces (Gray 1943: 324-36). Moreover, while altars were located exteriorly, the event was participatory, inviting the public gaze. While the sacrifice was performed by specialized priests and directed toward a particular god, the sacrifice-event was particularly geared toward the social cohesion of its participants, and certainly involved them in a general sacral ethos (Scheid 2007: 270). At the same time, temple precincts were more than simply the cella and often provided meeting rooms and banqueting facilities for cultic participants. Thus temple activity was not as exclusive and exclusionary as has been proposed. More significantly, imperial basilicas, although different in architectural form from temples, served similar cultic functions, but for the benefit of the state and emperor rather than a particular god. Images, altars, and offerings populated basilicas too. Notably, the temple and basilica forms shared not only cultic-behavioural linkages but also architectonic ones. As the archeologist Beat Brenk makes obvious, it is the privileged role of the apse in Roman architectural contexts, along with either frescoed or dimensional imagery, which denotes the presence of the sacred or location of cultic action (2010: 34-49). The apse emphatically permeates the architecture, not only of Roman temples, but also basilicas, other monumental public works, private cultic spaces, and the domestic residence. Thus, while the temple exterior was solely the domain of the pagan cityscape, its interior design, and, more importantly, associated functions and meanings were not—these elements were shared to some extent with the basilica.

25 The ambiguity that existed between temple and basilica suggests that the ordinary Christian worshipper in the experience of spatial relations and visual settings could not contend that their basilican space was merely secular or functional. Rather, quite the opposite is the case. First, as already noted, such categories were absent prime fascia in the ancient world. Second, the temple and imperial basilica had too much in common. Basilican space offered to the viewer material and functional cues indicating concurrences with temples in as much as a concept of cultic action and divinity were interrelated by the two architectural forms. To be sure, a tension existed since, as the Christian writer Athanasius (296-373 CE) indicated, it was rather nonsensical for Christians to speak of God without place (chōris topou) or in place (en topō), as the Christian god was thought to be the very cause of such categories (Meijering 1974: 16). Unlike their pagan counterparts, Christians obviously did not believe in a building containing a direct theophanic presence of their god (demonic presences in temples were possible!), but even Athanasius refers to churches as temples, thereby indicating a special rapport between the believer and a particular place (1886, vol. 28: 769). The Christian-use basilica within the context of religious experience did not, nor need not, house a deity as the temple cella did. In fact, religious experience in the Roman world rarely relied upon outright theophany. Roman religion was highly ritualistic and mediated, and so, in similar fashion, the Christian space-conditioned experience of the divine could really be indicative of an encounter with the sacred nonetheless, without conceding a direct theophanic presence contained within an idol, totem, or walls. As the theologian Yves Congar points out, the notion of a divine presence in a given place always implies an active presence; the god is understood to be present in the place where the god is active (1962: 93). For Christians, the rapport between presence and actions would be easily associated with the salvific action of God in the life of the believing community in its particular place of worship or prayer.

26 The extent to which Christians did appropriate temple concepts in the spatial-architectonic adoption of the hall-church (aula ecclesia) and basilica was not determined simply by the happenstance or purposeful appropriation of an architectural form driven by economics, practical spatial needs, or imperial patronage. Christians were already conceptually predisposed to accepting the temple theme that transcended both the architectural form of the temple and basilica. Contrary to Deichmann’s assertion discussed at the opening of this article, rather than serving to de-materialize and spiritualize the place of worship, and in effect prohibit the concretization of temple space, Pauline and Johannine biblical texts provided both a rationale for invoking the temple theme and offered a material model which Christians would eventually take up.

27 On the part of Paul, it is interesting to note that his writings develop an entire spatial metaphor regarding temples and the Christian community. Paul first invokes the theme when calling the Christians at Corinth the “temple of God” (naos theou) in 1 Cor. 3:16-17. Drawing upon Jewish temple concepts, Paul references the theophanic presence of Exodus 29:43, which served to establish the place of God’s presence for the Israelites. In a similar fashion, Paul asserts, sacred space is created for Christians through the divine presence too. The community, like the temple, is consecrated by a presence of the Spirit dwelling within the community. The space of the temple is the community: “God’s temple is holy, and you are that temple.” (1 Cor. 3:17). The scripture scholar Peter Leithart thoughtfully concludes that at stake in the text is more than mere metaphor or simply literary images (2002: 119-33). Clearly, Paul does not abandon the categories of the temple, nor the idea of sacral presence. It appears again in the Christian community’s concrete existence. This is to say, in speaking the way he does, Paul bequeaths to the Christian tradition the propensity to think in terms of temple categories and its spatial relationships in the formation of Christians’ self-conception. Johannine biblical writings function much the same way.

28 In the Gospel of John, the Jewish expectation of an eschatological temple is equated to Jesus, who himself is the presence of God in the world. The Jewish Temple therefore becomes displaced (heavenly) in the person of Jesus when he ascends to his Father after the Resurrection. The author also seems to be offering an explanation of why the Jerusalem Temple was destroyed—the book being written after the event—and what happened to the divine presence it housed. In this respect the gospel delocalizes the Jerusalem Temple, displacing it to the “space” of the heavens. Yet this delocalization serves to emphasize the transcending cosmic nature of the temple theme, accentuated by several significant symbols traditionally associated with it, rather than eradicating the concept. The Edenic garden and its life-giving rivers believed to emanate from within the Jerusalem Temple Mount become primary symbols of the heavenly temple where Jesus is worshiped (Um 2006, vol. 312: 20-21, 27). As a result, Christians would associate worship of Jesus with the image of a temple. What went up then comes down, as the Christian mind subsequently associates the worship of Jesus in the heavenly temple (see Revelation 5:10) and its paradisiacal symbols to every place of earthly worship in which the Christian community gathered. Through this Johannine radicalization of the temple theme it becomes possible for Christians to conceive of a heavenly temple truly present in a multiplicity of earthly locations, thus adopting a very materialistic understanding of the temple and the divine presence that fills it. For this reason, early Christian art, especially in the apses of churches, will come to bear images of the four rivers and Edenic garden—these places are the eschatological temple (Fig. 5).

Display large image of Figure 9

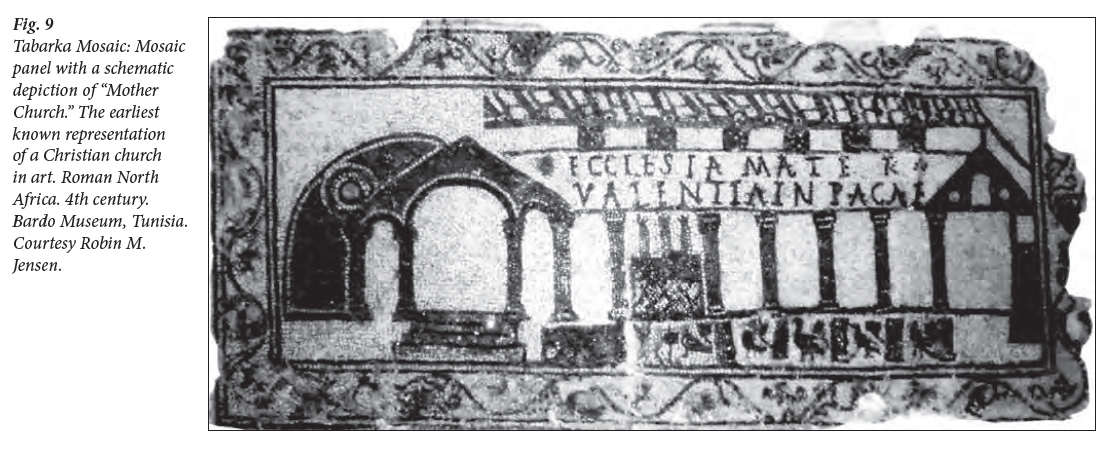

Display large image of Figure 929 In the Christian material record, the temple theme emerges strongly at the turn of the 4th century (McVey 2010: 41). Dependent upon Pauline and Johannine images of the temple the Christian community was coming to see itself as a historical replacement of the earthly Jerusalem based upon a typology of the destruction and refounding of the temple. Christians, having suffered persecution and undergone the destruction of life and property, now found themselves favored by Roman Empire and gifted with advanced building programs. These historical factors, including the favourization of authorities and the decline of competing religious locales, built up a further comfort in appropriating traditional temple concepts to church buildings. In the right historical moment, the temple theme would come to be articulated physically by the Christian community. Because a temple existed in the community’s sacred scripture as a material reality with a concrete identity, to read of it was to consider an eminently sacred space, with its physical conditions of horizon, expanse, texture, and architectural form. As actual Christian space was less pressured by its surrounding culture, the more a material perspective and particular architectural model could move from a conceptual textual location, from the de-spatialized “heaven” found in scripture, to that of the concrete location of the insular block of the cityscape. In fact, it is during this time that the first image of a Christian church appears in the late antique world, in the famous North African mosaic of Tabarka. The mosaic portrays a triple portico, an apse, a nave with centralized altar, and images of birds, likely indicating a paradisiacal floor mosaic—representing the temple theme (Fig. 9).

30 This process of articulating and modelling the heavenly temple transposed to the actual buildings of Christians is clearly evident in the writings of the church historian Eusebius of Caesarea (263-339 CE) and his near contemporaries. Several Hellenistic and Roman Jewish sources of the period, along with John’s gospel and Clement of Alexandria, refer to the rededication of the Jewish temple after the Babylonian captivity, which celebrated the return of God’s presence (McVey 2010: 50). Christians utilize the temple dedication references of the period, appropriating the idea to their own buildings. When Eusebius takes up the image in his inaugural address given at the dedication of the new cathedral in Tyre (ca. 314), he is concerned, “with the actual church building as a concrete symbol of divine presence and protection,” even equating the church’s altar to the cella (Holy of Holies) of the Jerusalem Temple, and in so doing makes a “new statement about the holiness of Christian places of worship” (McVey 2010: 53). Although the building of which Eusebius speaks is basilican in form, he interprets the building as a temple. The building is modelled, at least in his text, upon the New Testament heavenly temple. Through the linguistic turn of phrase, the biblical image mutates into the structure of the basilica in which he is standing, thereby appropriating Christian buildings to their heavenly counterpart. As Eusebius shows, Christians come back to the temple when space is available and secure, in a post-Diocletian era, and pre-Christian religion is fading. Full acquisition of the temple theme takes place approximately one century later when Balai of Aleppo (ca. 381-459 CE) will go as far to say that the church building is not simply a counterpart to the heavenly temple, but is actually heaven on earth (McVey 1993:337). In the final repost to Deichmann’s view of Christians, Maximos the Confessor (580-662 CE) interprets the biblical Epistle to the Hebrews not as securing a type of spiritual dematerialized Christian attitude toward the Jerusalem Temple and sacred space, but as the pattern for and interpretation of the material Christian cult (see Maximos 1982). Hence, the evidence argues that Christians engaged, elaborated, and created sacred space as they were capable, rather than in spite of themselves, as Deichmann would have it.

Conclusion: A Re-positioned Christian View of Sacred Space

31 Considering the whole of what can be known of early Christian material culture does not indicate a radically iconophobic, anti-materialist sect. Analyzing what can be garnered of Christian attitudes toward sacred space in its first centuries through the material record, rather than imposing determined theological judgments of what one thinks the community should have been, frees the evidence to more clearly represent the group and the spaces they ritually inhabited. Therefore, in light of what has been argued, the historian Charles Pietri rightly speaks of an ambiguïté in the early Christian community:

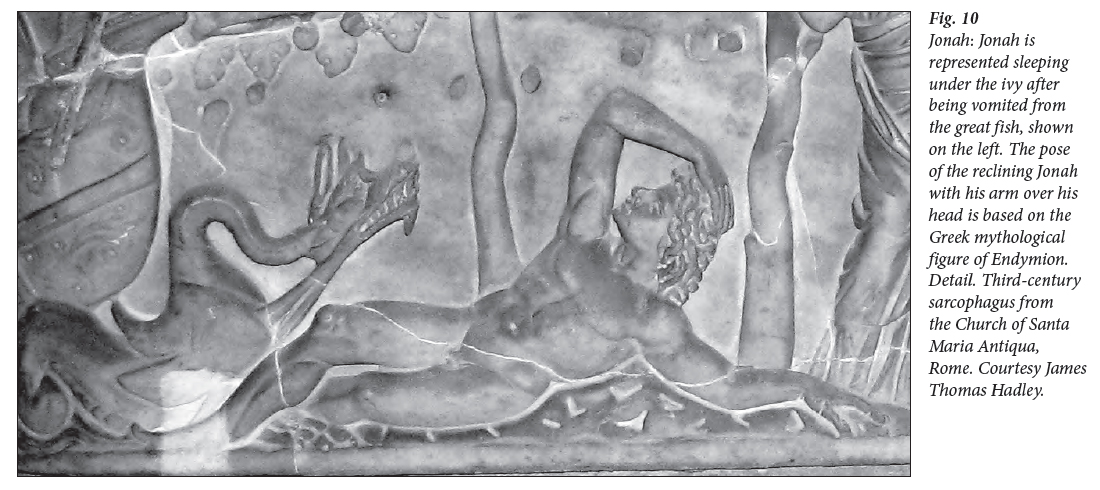

Display large image of Figure 10

Display large image of Figure 1032 This ambiguous disposition, Pietri suggests, is characterized by the Christian artist’s amalgamation of the Jonah’s Dream and the image of Sleeping Endymion–cultural adaptation at once syncretistic and valorizing (Fig. 10). Such ambiguity seems to have touched as well spatial relationships to cultic places. Even in the ancient environment permeated by cityscapes replete with public manifestations of religiosity, especially in the form of vibrant monumental and ever-present temples, Christians, too, opened up space to religious experience. In a highly external religious culture that often pressured Christian worship at its origin to internal spaces, Christians nonetheless chose, or, in the case of the catacombs, found, their own spaces of religious significance not unlike larger communal patterns of behaviour. In fact, White suggests that persecutions often ensued when Christian places became publicly recognizable as such, thus appearing in conflict with the larger visual space of the city or town and all the religious and political meanings implied therein (White 1990: 132-39).

33 The material evidence investigated above does not provide full clarification regarding precise Christian connotations of space and the sacred. It does suggest, though, that the architectural and artistic mode of Christian groups, as illustrative of real experiences and attitudes, was developmental and non-normative from the outset, rather than a fixed and prescribed relationship established in Urchristentum that was overthrown and violated in the 4th century, when Christianity itself came to permeate the built environment. Essentially, the historical evidence of the material culture more readily comports with a religious attitude that sees in materiality and spatiality an essential relationship to religious experience. Thus, as first suggested by Mary Charles Murray, there is no need for convoluted theories accounting for the advent of surprising, sudden, and intense material culture at the end of the 2nd and beginning of the 3rd centuries, necessitated by conventional theories of Roman imperial contamination (1977: 343-45). Christian material culture shows a trend toward these developments embedded in the believing community itself. To press the point further, as the historian Georges Duby has noted, a group’s religious conception of the sacred in non-stable environments is typically bound to transportable objects rather that architectonic structures that are communally unsupportable or that might have to be abandoned (2000: 5, 15). More likely, then, Christian conceptions of cultic space never were overtly anti-sacral and, later, positive formalized attitudes toward the material mediation of the sacred found in writing, liturgy, and behavior were not a divergent or contradictory development. This conclusion comports with various other factors observed within early Christianity and during the Constantinian peace, involving issues of sacrality in the multiple spatial contexts of Christian worship and even whole Christian topographies: the stability of religious sites; formalized ritual concerning architecture; the creation of baptisteries, catacombs, and the confessio; the Christianization of the Roman cityscape; practices of pilgrimag;, and the imitation of the shrines and liturgy of Jerusalem.

34 Reconsidering the broader array of Christian material culture shows that the theory asserting a perpetual and radical separation of spatiality and the sacred, little more than a “purist” imputation upon the cognitive world of Christianities in their early formative centuries, to be distortions of the material record. An alternative view of the evidence given by the study of material culture provides a framework in which to suggest that Christians were not radically iconophobic, aniconic, and purposefully anti-spatial in their belief or cultic practice. Indeed, the evidence shows to the contrary that Christians were more conventional and akin to broader social patterns of behavior in the late antique world, especially exhibiting a willingness to locate the sacred in space. The artistic and architectural record reveals that Christians exercised purposeful choice in siting and arranging their cult location, and were well-disposed to artistic elaboration—neither behaviours indicating anti-sacral uses of place— doing so before, during, and after imperial patronage. Additionally, the development of temple language suggests the purposeful adoption of an architectural image that reflected an ideological ease with the associated experiential categories in late antiquity. The temple model evoked quite culturally traditional and alive values, to which were added valorizing adjustments particular to the Christian faith. This review of the forensics of Christian attitudes is not to suggest a clear or conceptually simple evolution of the topic, as if to simply invert the troubles of Deichmann’s thesis. Just as Michael White determines that synchronic diversity of architectural practice leading up to and during the time of Constantine was the norm (White 1991: 147), Christian attitudes regarding the sacred in space likely reflected a similar malleability. The view offered in this article, similar in thought to Mary Charles Murray, Paul Corby Finny, Robin M. Jensen, and David Brown, is meant to show an overall acceptance of the relationship between spatiality and the sacred in religious experience of Christians from the outset; Christians were not opposed to seeing the sacred in space. Their buildings did not contain the direct theophanic presence of the Christian god. But they were provocateurs of encounter with the power and mysteries of the divine. One supposes this dynamic occurred intuitively at the origins of Christianity in non-formal ways before the possibility of material expression and expansion.