Articles

M. Lillian Burke (1879-1952): Three Lost Chéticamp Carpets

Abstract

Mary Lillian Burke was an American artisan who, with the support and encouragement of Alexander Graham Bell’s daughters, Elsie Grosvenor and Marian Fairchild, created the Chéticamp hooked-rug cottage industry in the 1930s. From 1927 to 1940, Lillian Burke designed and marketed Chéticamp hooked rugs for leading New York decorators. Today, Lillian Burke’s creations are virtually unknown. Despite their commercial and artistic success, not one of the Chéticamp rugs Lillian Burke sold in New York City has ever been identified. In an effort to gain an appreciation of Lillian Burke’s creations, “Three Lost Chéticamp Carpets” examines contemporary press reports, Burke’s original designs, and photographs of three of her outstanding creations.

Résumé

Mary Lillian Burke était l’artisane américaine qui, avec le soutien et l’encouragement des filles d’Alexander Graham Bell, Elsie Grosvenor et Marian Fairchild, créa l’industrie artisanale du tapis hooké de Chéticamp dans les années 1930. De 1927 à 1940, Lillian Burke créait et vendait des tapis hookés de Chéticamp aux grands décorateurs newyorkais. De nos jours ses créations sont pratiquement inconnues. En dépit de leur succès tant commercial qu’artistique, pas un seul des tapis que Lillian Burke a vendus à New York n’a pu être identifié. Afin de mieux apprécier la qualité propre de ses créations, « Trois tapis (space) perdus » réunit des articles de presse contemporains, des dessins originaux de Burke, et des photographies de trois créations remarquables.

And all doth waxe, and fostred be,

And all things destroyeth he…

Guillaume de Lorris, The Romaunt of the Rose (tr. Chaucer)

Display large image of Figure 1

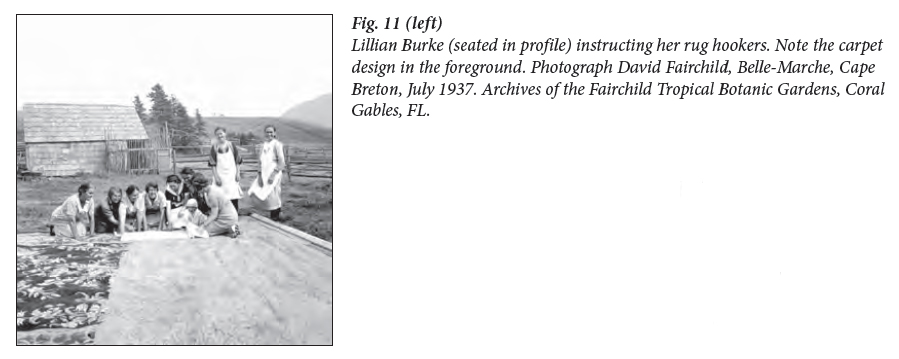

Display large image of Figure 11 This paper tells the story of three Chéticamp hooked carpets designed in the 1930s by the American artisan, rug designer, and entrepreneur, M. Lillian Burke (1879-1952). A recently discovered collection of Burke’s art work, comprising one hundred and eighty four hand-painted designs for Chéticamp hooked rugs, encourages scholarly interest in the grade-school teacher from Washington, DC, who, with the support of Marian Fairchild (1880-1962) and Elsie Grosvenor (1878-1964), founded a hooked-rug cottage industry in rural Cape Breton.1 From 1927 until 1940, during the bleakest years of the Great Depression, Cape Breton Home Industries (CBHI) marketed hundreds of Chéticamp hooked rugs in Baddeck, New York City, Montréal, and elsewhere. In New York, Burke’s bespoke rug designs found favour with leading metropolitan decorators, and throughout the 1930s Chéticamp rugs were commissioned by America’s most prestigious decorating firms. In addition to her up-market clients, Burke’s flair for textile design caught the attention of rug-hooking enthusiasts like A. M. Laisé Phillips, of Hearthstone Studios, the architect Winthrop Kent, and the godfather of the American hooked rug fraternity, Ralph Warren Burnham (Kent 1941: 31). At home, Alice Peck and Wilfrid Bovey of the Canadian Handicraft Guild (CHG) wrote enthusiastically of Burke’s Chéticamp hooked rugs, praising their outstanding design and execution (Peck 1933; Bovey 1934: 553).

2 An appreciable number of Burke’s hooked rug sketches have survived but, sadly, the rugs she created have all but disappeared.2 Despite their commercial and artistic success, not one of the Chéticamp rugs Lillian Burke sold in New York City has ever been identified, let alone subjected to rigorous provenance research, most likely because CBHI did not label its products. The Textile Museum of Canada does not display a single Lillian Burke design. The same is true of both the McCord Museum and the Canadian Museum of History. At the outset of this essay, let us state that one of our goals is to alert the custodians of Canada’s material heritage to this unfortunate, but perhaps reparable, oversight. It is to be hoped that Burke’s hooked rug sketches and photographs will one day help identify her lost work.

3 In the absence of the rugs Burke created, handcraft historians have eschewed commenting on her artistry, focusing rather on the social and economic significance of her work (McKay 1994: 203-205; Neal 1995: 111-23; McLeod 1999: 188, 191; Flood 2001: 104-13). It is worthwhile recalling that Burke was not a social activist per se, but an educator and a highly trained crafts-woman skilled in bookbinding, educational sloyd (woodworking), the graphic arts, sculpture, and metalwork, as well as textiles (Langille 2013: 50). It seems only fair that her legacy should be assessed in artistic rather than purely social terms. And therein lies the rub. How can we evaluate Lillian Burke’s artistry without examining the actual carpets she designed?

4 The question is more exigent than it first appears. Consider for instance the treatment Lillian Burke is given by the historian Ian McKay. Under the opprobrious term of the “urban appropriation” of handcrafts, McKay flatly accuses the designer of “reinventing cultural tradition” merely for profit. McKay argues, among other things, that Burke paid her workers a pittance, that she “scientifically redesigned” the Chéticamp hooked rug, and that in the process, she contrived to sabotage traditional Nova Scotia folk art, summarily described as “locally designed products carrying images of fishing life” (McKay 1994: 205).

5 McKay’s indictment is quite inaccurate. Traditional hooked rug design has never reflected a single theme. Atlantic Canadian hooked rugs, including those produced in Newfoundland, have always depicted an eclectic variety of patterns including floral, floral geometrical, abstract geometrical, still-life religious, still-life nautical, landscapes, and portrayals of animals (Lynch 1980). A favoured technique universally practised consisted in copying textiles in hooked work (Pocius 1979: 277). Traditional rug hooking often took its inspiration from old pieces of fabric such as paisley shawls, cretonne, chintz, or calico prints. Even sophisticated French carpet designs were given homespun treatment (Kent 1941: 215). But in any event, we know that by the early 20th century Chéticamp hooked rugs were most often made from pre-stamped canvasses provided by John E. Garrett and Son of New Glasgow (Chiasson 1985: 26).

6 The imputation that Lillian Burke made a fortune designing Chéticamp hooked rugs has been dealt with elsewhere (Langille 2012: 76). Let us state emphatically that, contrary to rumour, Burke did not grow rich designing Chéticamp hooked rugs. Even at the height of her career, Burke’s income was modest, especially by New York standards. As for the accusation that her Chéticamp workforce was paid a pittance—75¢, 85¢, or $1.00 per square foot of hooking—a 1935 memorandum circulated by the Canadian Handicraft Guild to its affiliates allows us to put CBHI’s wages in perspective. That memorandum stipulates a flat retail rate of $1.10 per square foot of hooking for rugs consigned for sale in its Montréal shop. An added note makes clear that “quotations will be given for special designs.”3 If we take into account the workers’ wages, the commission paid to Burke’s agent, her own fee, the cost of the chemical dyes, plus handling charges, it seems indubitable that CBHI’s profit margins were slight at best.

7 McKay’s belief that Lillian Burke subverted traditional folk art is a vexed question. That Burke taught the women of Chéticamp improved rug-hooking techniques, and a great deal else, is beyond dispute. That she tailored her designs to suit the taste of wealthy clients is also true. None of this, however, can honestly be described as “scientific redesign.” The difficulty lies in McKay’s definition of the folk and how he applies that definition to home arts of the 1930s. In line with a romantic appreciation for so-called genuine folk art (e.g., self-taught artists), McKay promotes localism and disparages outside influences, especially when these emanate from the social elite. By allowing the Other to define beauty, he argues, the folk artist submits to a type of cultural imperialism. What McKay fails to acknowledge is that this comparatively recent view bears no relation to the handcraft thinking of the 1930s, or earlier. During that period, the idea that unschooled (or crude) artistic execution could somehow qualify as decorative art would have baffled all but a few eccentrics. On that point, C. Marius Barbeau, ethnologist at the National Museum of Canada in the 1930s, declared, without irony, that rug hooking “with its bad dyes, poor materials and uninteresting design [was] a bastard art.”4 As late as 1950, Antiques magazine could ask in all earnestness “What is American Folk Art?” It was, in fact, not until 1961, almost ten years after Lillian Burke’s death, that that the American Folk Art Museum in Manhattan received its provisional charter and opened its collections for public viewing. In light of folk art’s uncertain status during her lifetime, it seems unreasonable to expect Lillian Burke’s views on the subject to conform to a latter-day definition.

8 In order to understand Barbeau’s attitude (and, by inference, Lillian Burke’s as well), we must briefly consider the impact the Arts and Crafts school of thought on the home arts movement. Rejecting mass-produced goods, William Morris (1834-1896) and his followers advocated high quality, traditional craftsmanship, simple forms, and “folk” styles of decoration. Morris’s credo was anti-industrial (e.g., opposed to scientific redesign), and yet, no one today would consider the cosmopolitan Morris a promoter of folk art. His thinking nevertheless greatly influenced the early home arts movement which, first in Britain, then elsewhere, sought to enhance, promote, and protect rural handicrafts. Today’s folk art aficionados may reject professional design and fine arts training; they cannot deny that the Arts and Crafts movement was an indispensable precursor to the modern-day appreciation for folk art in all its forms. As Paula Flynn has written, the early craft industry everywhere was entirely dependent on, and indeed indebted to, “outsider influence” (Flynn 2004: 24).

9 Imbued with Arts and Crafts ideals, Lillian Burke’s take on the hooked rug was consistent with Morris’s basic principles. She was naturally disdainful of commercial hooked rug kits, and quite adamant that hooked rug factories would never come to Chéticamp (Cox 1938: 68). Burke’s trademark was the use of tightly hooked two-ply new wool, rather than rags, a preference for “old” colours harmoniously combined, and, of course, professional design. More than ten years after Lillian Burke began working with the women of Chéticamp, the journalist Corolyn Cox revealed something essential about Burke the artist. In a 1938 Canadian Homes and Gardens article, Cox explained how decades of training gave Lillian Burke the artistic vision required to transform what had been nothing more than a local craft into a profitable cottage industry. Throughout this period, Burke’s goal, arguably, was not to redesign the Chéticamp hooked rug, but to refine it. For only with improved hooked rug manufacture and design could she successfully obtain commissions in New York’s competitive textile market on behalf of the women of Cape Breton.

10 Before turning to the three carpets that are the topic of this paper, let us set forth some questions we hope to address. Our first concern is methodological. Why these carpets, and why three? How can we evaluate the artistic merits of a carpet, without having seen it, if that carpet is lost? We must also ask ourselves why it should matter that these carpets (and others) have been lost. Is their disappearance relevant? Would their discovery tell us something new about Lillian Burke’s life and work? Finally, and interestingly, what insights can the lost carpets provide into the lives of the women who made them?

11 Let us begin by saying that the carpets we have selected for study were judged outstanding achievements at the time they were created. As a result of their recognized artistic merit they were photographed, written up, and, in one case, documented by a leading scientist. The photographs that have come down to us allow us to work backwards, as it were, from a picture of the finished carpet to Burke’s design sketches and hand written instructions. In order to gain as accurate a picture of the carpets as possible, we have taken into account contemporary descriptions and other information, allowing us to chronicle the work post creation. Viewed as a whole, these data allow for an aesthetically informed description of Burke’s lost creations, as well as a highly focused glimpse into the social context in which the carpets were created.

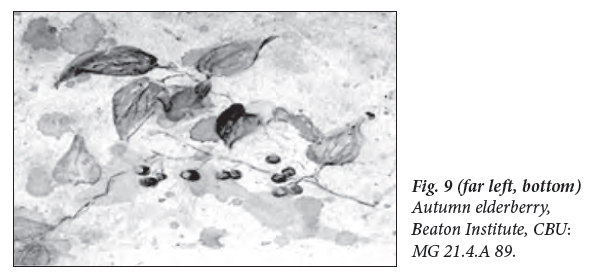

12 The first hooked carpet we shall discuss is a handsome “bird and plant” rug, featured in Corolyn Cox’s 1938 article “The Rugs of Chéticamp” (Cox 1938: 64). This creation was commissioned by Thedlow Inc. for the Long Island home of Mrs. Elmore Coe Kerr. Of the many hundreds of hooked rugs designed by Lillian Burke for the New York market, the “bird and plant” rug is the only one, to date, whose purchaser can be identified, along with the decorating firm that placed the order.

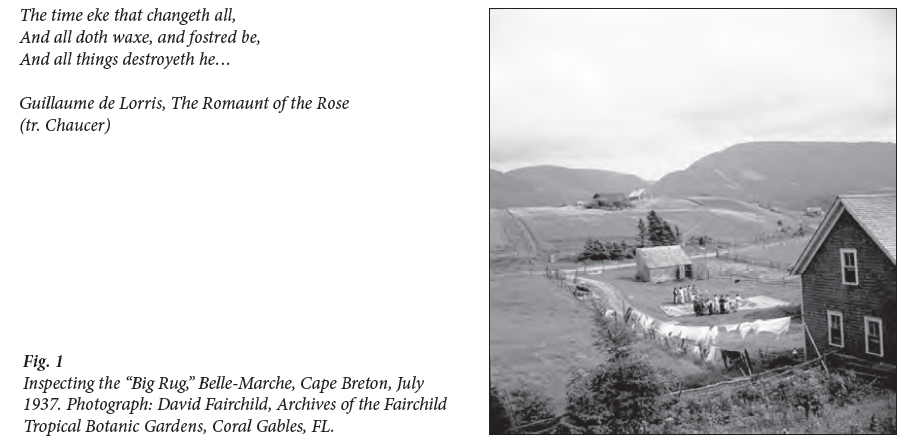

13 The second hooked rug is a 648 sq. ft. (60 m2) Savonnerie-style carpet that became famous as reputedly the largest hand-hooked carpet ever manufactured. Remarkable for its size as well as for the intricacy of its formal, 17th-century design, the “Chéticamp Savonnerie” was so stunning that it was photographed in July 1937 by the botanist David Fairchild (1869-1954). Fairchild’spocket notebooks, notations from Cape Breton, contain valuable information not hitherto considered about the carpet’s manufacture. In addition to this, a photograph displaying the carpet in the room for which it was designed was published by the architect and hooked-rug connoisseur William Winthrop Kent, in 1941 (Kent 1941: 77).

14 The third carpet we shall consider is, in some ways, the most intriguing. In the autumn of 1938, Lady Tweedsmuir, wife of Canada’s governor general, bought a William Morris-inspired Chéticamp mat at the Canadian Handicraft Guild stall at the Canadian National Exhibition (CNE) in Toronto. A Montréal newspaper some months later reported that the carpet was bought in anticipation of the 1939 royal tour, and that it was intended for Queen Elizabeth’s bedroom at Government House (Rideau Hall), official residence of both the Canadian monarch and the governor general of Canada. The “Queen’s rug” was photographed by no less a celebrity than Yousuf Karsh. That photograph, along with commentary, was also published by William Kent (Kent 1941: 30-31). The whereabouts of the queen’s Chéticamp rug is the subject of the third and final part of this essay.

The Long Island “Bird and Plant” Rug

15 Lillian Burke’s flair for depicting wildlife in wool found expression in a large bird-and-plant hooked carpet commissioned by Thedlow Inc. for the library of the Long Island home of Mrs. E. Coe Kerr (Marian Kerr of Mill Neck, NY).

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2 Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3 Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 416 Thedlow was one of the oldest interior decoration firms in the United States. Founded in 1919, the firm derived its name from the first two letters in the names of the original partners: Theresa Chalmers Baker, Edna de Frise and Charlotte (Lottie) Chalmers Handy. The “w” stood for work. Mrs Handy’s preference for hooked rugs can be evidenced by a number of contemporary publications, including Ross Stewart’s 1935 Home Decoration: Its Problems and Solutions (Stewart 1935:122). Interestingly, until 1939 Thedlow Inc. was exclusively staffed by women.

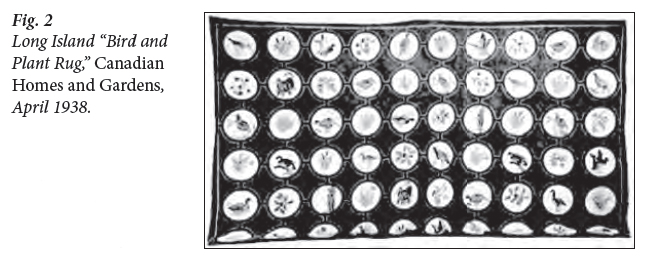

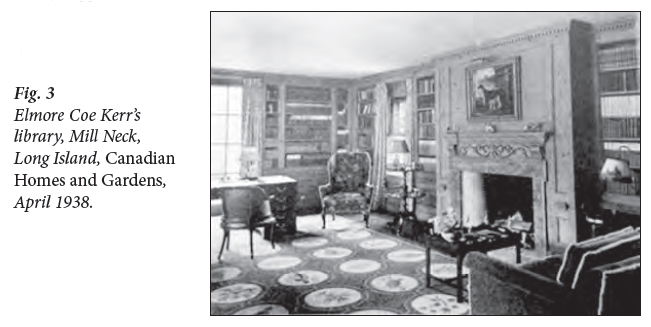

17 In April 1938, Canadian Homes and Gardens published two small black-and-white photographs of Marian Kerr’s Chéticamp carpet (Cox 1938: 64). The first photograph (1.5 x 2.75 in [3.8 x 7 cm]) shows the carpet’s structure and polk-a-dot pattern: sixty cream-coloured circular cartouches, ten rows along the length and six along the width; hooked in beige wool on a dark background; and the whole framed by a thin, light border (Fig. 2). The second photograph (2 x 2.75 in 5 x 7 cm) displays the carpet in the library for which it was designed (Fig. 3).

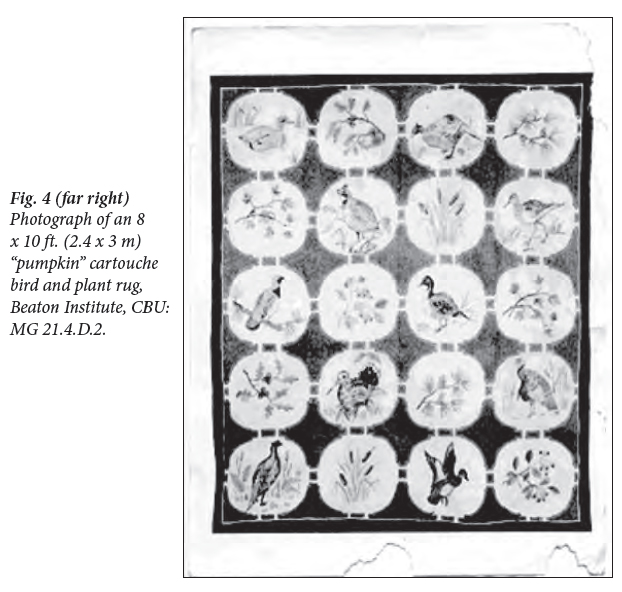

18 Discernible in Fig. 2 are the alternating bird and plant motifs that give the carpet its name. In the Kerr carpet,Burke’s motifs were aligned in an upright position along the carpet’s length. This is not the case in Fig. 4, which show a finished 9 x 12-ft (2.75 x 3.6 m) carpet in which the birds are aligned upright along the carpet’s width.

Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 819 Figure 4 is instructive, nevertheless, because it indicates the scale of Burke’s bird and plant design. We note here, for example, that the interconnected cartouches are pumpkin shaped rather than circular; also, that the same birds and plant bouquets appear in more than one carpet (Figs. 2, 4 and 9). We can thus surmise that Burke designed a selection of bird-and-plant rugs, and that her wildlife motifs were applied to various background schemes, depending on the orders she was filling.

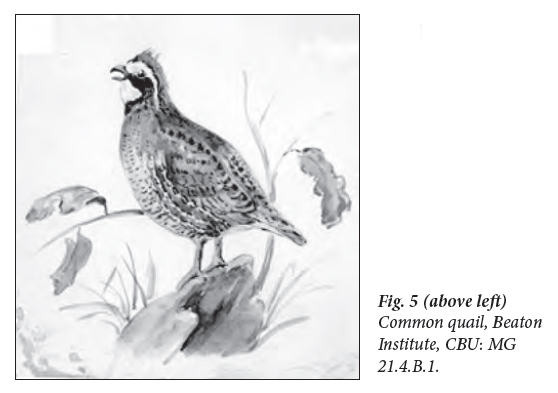

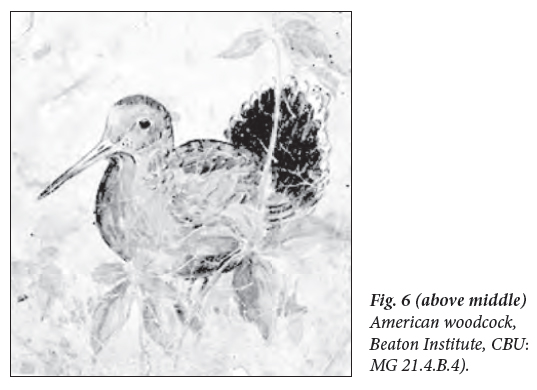

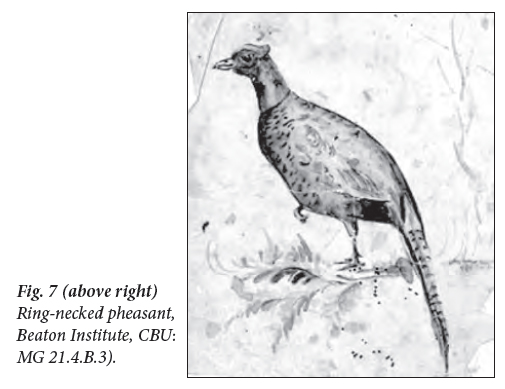

20 By no means quaint, the Long Island bird and plant carpet’s wildlife theme reflected Mill Neck’s woodlands, creeks, meadows, and salt water marshes. Of the thirty birds depicted, we identify a common quail (Fig. 5), an American woodcock (Fig. 6), and a ring-necked pheasant (Fig. 7), all remarkable for the Audubon-like detail of their plumage. Let us note in passing that these birds, and most of the others represented, are not native to Cape Breton Island.

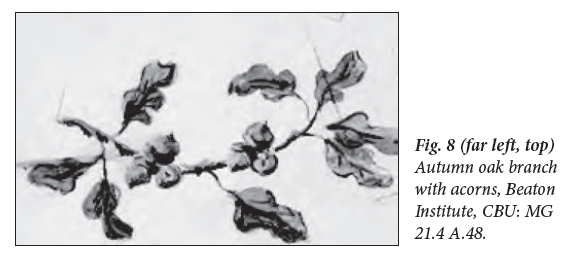

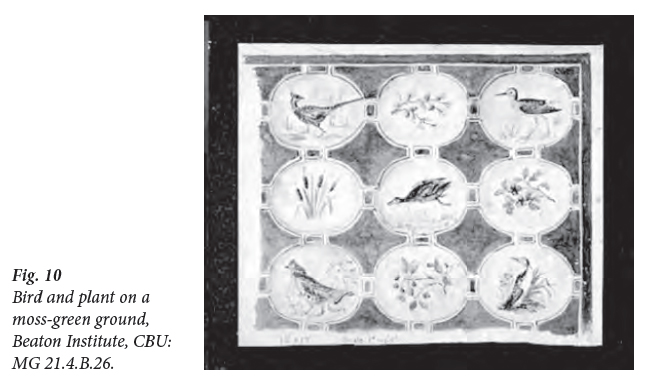

21 In examining Fig. 2, the photo of the Long Island carpet, we see that the plants are not as distinctly depicted as the birdlife. We can, nevertheless, identify a late-summer sprig of English oak (Fig. 8), elderberries on the branch (Fig. 9), a stem of Scotch pine with pinecones (Fig. 10), a spray of cattails (Fig. 10), and a bouquet of aquatic plants. The study sketches for plant motifs that are represented in Burke’s collection of hooked rug designs demonstrate the designer’s gift for drawing delicate vegetation. No less intricate than her paintings of wild fowl, Burke’s plant bouquets are a nod to the accuracy and precision exhibited by the masters of botanical engraving.

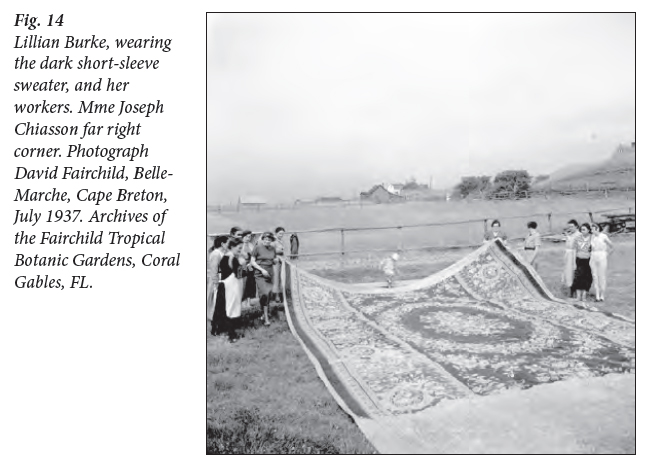

22 In the absence of the carpets she designed, what do Lillian Burke’s watercolour designs tell us about her ambition as an artist in textiles? Taking her lead from Flemish tapestry weaving and 17th-century rug manufacture, Lillian Burke sought to replicate in wool painterly elegance and precision. Essential to her concept of modern rug hooking was the dyeing technique needed to render her finely graded watercolours in pointillist hook work. The difficulty of achieving a painter’s palette in wool was matched by the technical skill required to execute Burke’s curvilinear patterns.

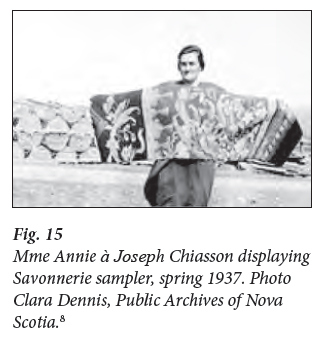

23 Another feature of Burke’s sketches for the bird and hooked rug is their adhesion to the classical principles of symmetry and proportion. Consider how the decorative vegetation softens the images of the birds within the cartouches, and how the birds face inward (Fig. 4). By manipulating their position, Burke directs the eye from left to right and then, diagonally, from top to bottom. The result is a tableau suggestive of a stylized natural setting. Burke’s designs confirm her aspiration to elevate domestic rug hooking into the higher sphere of the decorative arts.

Display large image of Figure 10

Display large image of Figure 1024 Thedlow’s scheme for Elmore Coe Kerr’s library incorporated panelled, well-stocked bookshelves, a fireplace and hearth, a sofa armchair, a drinks tray, and perhaps a billiard table. In Fig. 3, we note a gentleman’s writing desk in front of a floor-to-ceiling sash window and, between the windows, a high-legged Queen Anne wingback chair beside a three-tiered mahogany dumb waiter. Although Fig. 3 is black-and-white, the design prototypes viewed above suggest that the room’s colour scheme drew on the spectrum of autumn tones—buff, beige, soft brown, mustard, tawny, faded red, light green, slate grey and pale teal. By way of comparison, Fig. 10 shows a third bird-and-plant pattern against a brown-bordered, moss-green background, highlighted, like Fig. 4, by brighter interconnecting “=” shaped lines. This general colour scheme corresponds to the design sketches we can surmise Lillian Burke also used in the Long Island rug.

25 Returning to figure 3, the scale of the carpet in relation to the library’s furnishing allows us to estimate its size. Accordingly, the round cartouches must have measured roughly two feet in diameter. This detail corresponds to the 1 in=1 ft (2.5=30 cm) scale indicated in Fig. 4, where each oval cartouche measures 2.5 in, or 2.5 ft to scale (30=73 cm). With the edging and the space between the circles that would make the Long Island bird rug an impressive 15 feet wide by 25 feet long (4.6 x 7.6 m), or 375 square feet (35m 2 ).

26 Thanks to Burke’s designs we are able to reconstruct, as it were, the Kerr “bird and plant” rug, and to see how it was representative of Burke’s wildlife designs. Regrettably, we can say nothing about the women who executed the carpet. We do not know their names, how long they worked on it, nor how much they were paid.

27 What we can relate is that the rug remained in the Kerr family for three generations, from the late 1930s until 2006. Elmore Coe Kerr III reports that Burke’s “bird and plant” rug was a family heirloom, and that he acquired it after it had passed from his grandmother to his father, the New York art dealer Elmore Coe Kerr II (d. 1973):

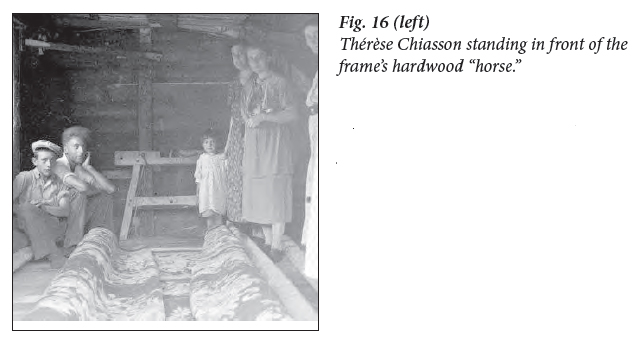

28 Responding to a further inquiry about the rug’s deterioration, Mr. Kerr stresses:

29 Let us end the story of the Long Island “bird and plant” hooked rug with this reflection on the materials used in CBHI hooked rug manufacture. Burke demanded impeccable workmanship, and would only allow high grade newly spun wool to be used in her carpets. In spite of rigorous quality control, CBHI’s Chéticamp hooked rugs were a proverbial house built on sand. Jute burlap or Hessian cloth, the inexpensive underpinning used in hooked rug construction, doomed Burke’s creations to slow disintegration. Naturally high in uric acid, burlap fibres rot (Lewin 2007: 481). The fold around the binding is the area where most hooked rugs begin to show signs of age. Direct sunlight, accumulated grit, outdoor shoes and vacuuming combine to accelerate the carpet’s deterioration. Over time, the sheer weight of a large wool rug would strain the dry, brittle jute fibres. With normal wear the rug would pull itself apart. This appears to have been the fate of the Long Island bird-and-plant rug.

The Chéticamp Savonnerie Carpet, 1937

Display large image of Figure 11

Display large image of Figure 11 Display large image of Figure 12

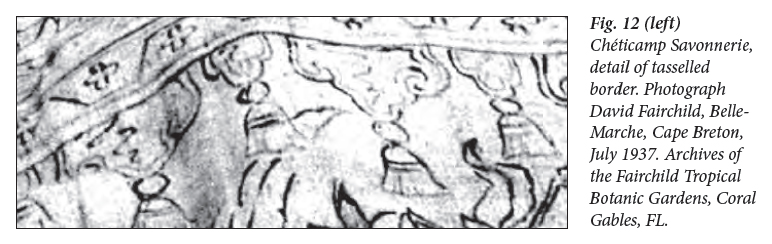

Display large image of Figure 1230 CBHI’s most elaborate project in the 1930s was 648 sq. ft. (60 m2) hooked rug copied from a 17th-century Savonnerie design. Commissioned in 1936 by the Persian Rug Manufactory (PRM), ostensibly for a Virginia client, the reproduction carpet was an ambitious creation worthy of its Baroque original (Brown 1940: 613). Lillian Burke’s take on the Savonnerie style combined densely massed flowers in huge festoons, leafy rinceaux, monumental heavily framed medallions within two structuring borders made up of tasselled swags and braided cables. Set against the traditional deep blue, black or dark brown ground, the carpet’s design was so intricate that it took Lillian Burke three months to block it out on the 18 x 36 ft. (5 x 11 m) burlap underlay, a task, we know, she carried out at the Lillian Mosséller studio in Lower Manhattan (Figs. 11, 12).

31 CBHI’s most elaborate project in the 1930s was 648 sq. ft. (60 m2) hooked rug copied from a 17th-century Savonnerie design. Commissioned in 1936 by the Persian Rug Manufactory (PRM), ostensibly for a Virginia client, the reproduction carpet was an ambitious creation worthy of its Baroque original (Brown 1940: 613). Lillian Burke’s take on the Savonnerie style combined densely massed flowers in huge festoons, leafy rinceaux, monumental heavily framed medallions within two structuring borders made up of tasselled swags and braided cables. Set against the traditional deep blue, black or dark brown ground, the carpet’s design was so intricate that it took Lillian Burke three months to block it out on the 18 x 36 ft. (5 x 11 m) burlap underlay, a task, we know, she carried out at the Lillian Mosséller studio in Lower Manhattan (Figs. 11, 12).

32 Established in 1886, the Persian Rug Manufactory (PRM) was for more than half a century the most highly respected carpet firm in the United States. Specialized in authentic reproductions of ancien régime designs, it dominated America’s luxury carpet market through its east and west coast branches. In 1943, PRM was acquired by Patterson, Flynn and Martin Floorcoverings. That company still operates today. Regrettably, PRM’s archives have not been conserved.

33 PRM’s commitment to historic French design was a company trademark. The 1911 promotional booklet it published, The History of French Rug Weaving, recounts the story of the Savonnerie (pile) and the Aubusson (flat weave) manufactories. On the booklet’s inside cover we find a sales pitch that gives us an idea why the Savonnerie order was placed with CBHI in the first place.7 PRM actively encouraged prospective clients to consider made-to-order rugs over antique ones. In order to facilitate the process, the firm boasted a research department and a “large stock of hand-painted sketches.” We can surmise that PRM provided Lillian Burke with just such a hand-painted sketch, which she then (painstakingly) adapted to the hooked-rug medium. PRM’s involvement in the project perhaps explains why no colour designs for the Chéticamp Savonnerie have come down to us. But unlike the “bird and plant rug,” the “big rug” was providentially documented as a work in progress by David Fairchild, and later by the journalist Corolyn Cox.

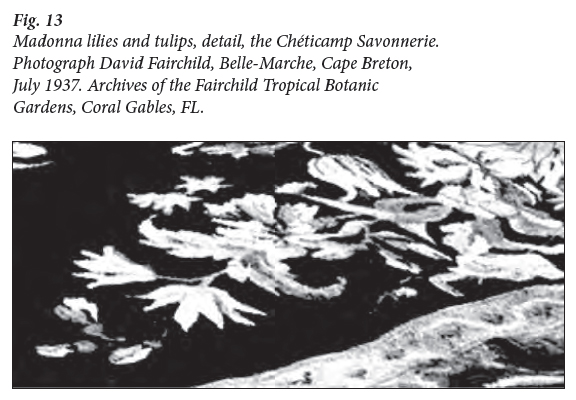

Display large image of Figure 13

Display large image of Figure 1334 Fairchild’s recently discovered black-and-white photographs allow us to see that the carpet’s dominant motif was the iconic Madonna lily (Fig.13) arranged in a central spray surrounded by an oval wreath and framed by four eyebrow-shaped floral garlands. Completing the design, each corner of the carpet’s central rectangular panel was bracketed by a triangular bouquet of white lilies intertwined with spring and early-summer flowers common to 17th-century Dutch still-life painting: tulips, fritillaries, ranunculi, cabbage roses, and so forth.

35 Lengthwise, the carpet was structured by two twisted-rope borders, the inner one with theatrical outward-hanging tassels (Fig. 12). The wide panels inside these borders feature an even denser profusion of floral sprays in an alternate pattern with the eight large œil de bœuf medallions mentioned earlier.

Display large image of Figure 14

Display large image of Figure 14 Display large image of Figure 15

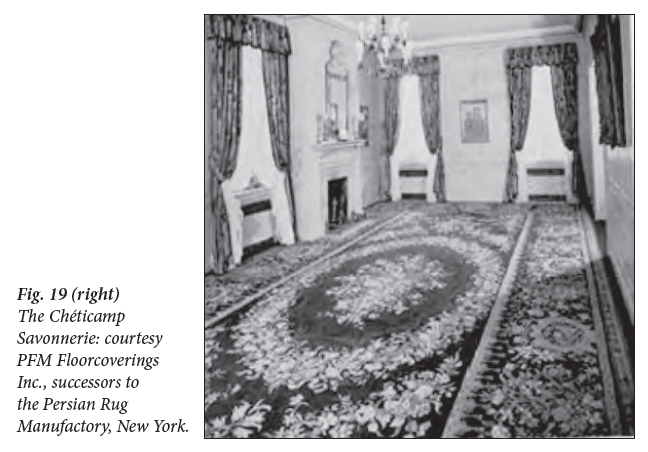

Display large image of Figure 1536 The French quality of the Savonnerie design lies in its imposing architectural structure married, paradoxically, to an almost whimsical use of floating ribbons and sinuous “S” curves. In the Chéticamp Savonnerie, the eye is repeatedly drawn around and into the colossal floral arrangements by the turning of flower heads, the reversing of leaves, and the curving of graceful stems. Massed groupings in 17th-century French decorative art (flowers, fruit, putti, armaments, musical instruments, etc.) were calculated to create a quasi-sculptural effect apposite to the grandest state interiors. We must wonder if Burke’s execution of this formal pattern in hooked work represented an attempt on the part of PRM to ally French opulence to homespun American domestic taste. Figures 14 and 19 show Burke’s overall design.

37 Our first glimpse of the Chéticamp Savonnerie comes by way of Nova Scotia travel writer Clara Dennis (1881-1958). Dennis began touring the province with car and camera sometime around 1930. A snapshot taken in the spring of 1937 shows a 2 x 5 ft (60 x 1.5 m) sampler held up by Mme Annie à Joseph Chiasson, of Belle-Marche, Cape Breton (Fig. 15). Mme Chiasson was put in charge of the Chéticamp Savonnerie, and it was she who hired the eight women who hooked it on the family farm. Since Burke insisted that the woman invited to take on a project first produce a sampler for colour and design approval, we can safely assume that the one Mme Chiasson displayed that spring day was of her own confection. Figure 15 illustrates the Savonnerie’s heavy tasselled swags, wide braided borders, and floral motifs. The lobster traps in the background tell us that the photograph was taken in April, before the beginning of the fishing season; the absence of green grass also indicating early spring. We know that Lillian Burke, in Chéticamp in March 1937, was facing significant labour trouble. The PRM order coincided with that unrest and may conceivably have been at the root of it (Langille 2012: 73).

38 The Savonnerie carpet was begun in May 1937 and took six months to hook. By the time David Fairchild and Corolyn Cox (on separate occasions) saw it, it was half completed. On July 28, 1937, Fairchild took thirty-five high quality black-and-white photographs of the carpet and its makers. Fairchild’s photographs constitute a rare and exciting period document. Along with the scientist’s accompanying pocket diaries, they provide a record of the Chéticamp Savonnerie’s manufacture, including the only document we have specifying how much money Burke’s workers were paid for their labours. Fairchild wrote that the return to the women was $900, or a record-breaking $1.38 per square foot of hooking. Presumably, the cash was not divided equally. These are the notes David Fairchild wrote on that day:

39 In another pocket-diary entry written after the photographs were developed, Fairchild added: “Ditto subject & place. There are 125 colours in it all dyed by Mrs Chiasson. German dyes.” He then added the names of the eight workers (with cringe-inducing spellings):

40 In a real sense, the Chéticamp Savonnerie was as much Annie Chiasson’s creation as it was Lillian Burke’s. Besides supervising the women who executed Burke’s design, Mme Chiasson was assigned the epic task of spinning and then dyeing 200 lbs (90 kg) of yarn. Spinning was routine labour, and once spun, yarn could be stockpiled. Blending 125 colours and dyeing the prodigious quantities of yarn required, on the other hand, demanded precision, a trained eye, and years of practical experience.

41 On the matter of yarn dyeing, Corolyn Cox’s eyewitness account, also recorded during the summer of 1937, describes Mme Chiasson in action:

Display large image of Figure 16

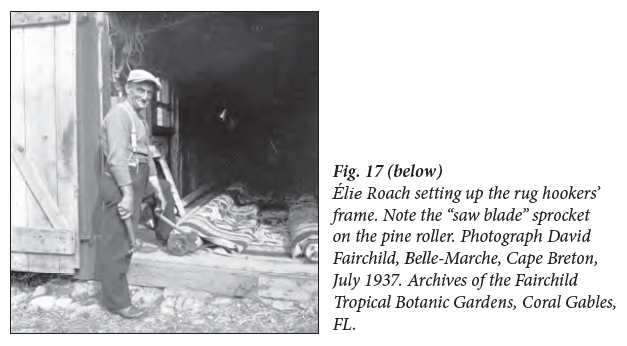

Display large image of Figure 16 Display large image of Figure 17

Display large image of Figure 1742 Anselme Chiasson (no relation) added to Cox’s description a further interesting detail. Mme Chiasson dyed her yarn on an outdoor stove set up alongside a ground-fed spring used to draw the water needed to mix the dye (Cox 1938: 68). How Annie Chiasson managed to ensure the yarn’s colour consistency in the above-described conditions quite simply boggles the mind.

Display large image of Figure 18

Display large image of Figure 18 Display large image of Figure 19

Display large image of Figure 1943 Meantime, Mme Chiasson’s father, Élie Roach, was also at work on the project, constructing the hardwood frame the rug was to be hooked on. Figure 16 shows little Thérèse Chiasson standing beside one of the carpet’s hardwood “horses” built by her grandfather to support the 20-ft (6 m) pine rollers. The slots at the top of the frame allowed the rollers, set on steel pins, to revolve, while the metal rods fitted beside them held in place an improvised “saw blade” sprocket fitted to each end of the logs in order to keep them from turning (Fig. 17). Corolyn Cox wrote that the Savonnerie rug was so large that “the hooking was commenced in the middle of the pattern” and that “the finished part [of the rug] was carried down through the centre [of the frame] through a slot, allowing the women to work without having to reach over the huge roll of hooked rug that would otherwise pile up” (Fig. 18). Lillian Burke was apparently so intrigued by Élie Roach’s frame design that she asked him how he came up with it. Cox reported that he responded blithely: “It came to me in a dream” (Cox 1938: 68).

44 Shipped by sea from Chéticamp to Baddeck, transported by train from Baddeck to Halifax, from Halifax to New York City, and then on to Virginia, the Savonnerie was professionally laid in the room it was designed for by a team from PRM. In the years following its manufacture it was featured in a number of periodicals, where it was touted as the copy of an antique original housed in the Louvre. We cannot validate this claim. Nor can we substantiate the assertion that the Chéticamp Savonnerie was the largest hooked rug ever manufactured. Cox included two photographs of the “big rug” in her 1938 Homes and Gardens article (Cox 1938: 64). A year later a third photograph was reproduced in a Montréal Standard article she wrote (April 1, 1939). Yet another photograph was published in a 1940 National Geographic Magazine piece titled “Salty Nova Scotia” under the caption “Finished at Last.” That caption is the only reference that the rug was made for a Virginia home (Brown 1940: 613). Let us add at this point that reports the Savonnerie carpet was manufactured for the Executive Mansion in Richmond, Virginia, are untrue.9

45 Our last look that the Chéticamp Savonnerie was published by Winthrop Kent (Fig. 19). A photograph provided by PRM shows the carpet in a long, narrow reception room (or perhaps dining room). Fitted as a wall-to-wall carpet, it appears that in order to accommodate the room’s hearth and chimney piece, a section of the carpet’s border was cut out. Unlike the Kerr bird-and-plant rug, the identity of its buyer has never been revealed, nor has its precise location ever been published. Attempts to identify the carpet through advertisements in specialist periodicals and social media have not thus far jogged any memories. For the time being, the Chéticamp women’s tribute to 17th-century France, ancestral homeland of the Acadian people, is lost to posterity.

The “Queen’s Rug,” 1939

46 Although the name Cape Breton Home Industries sounds impressive, the firm was throughout the 1930s a small business without significant assets or capital investment. Lillian Burke had no employees in New York, no research assistant, and not even a secretary or bookkeeper. Revealingly, from 1927 to 1940 one cannot point to a single advertisement for the Chéticamp hooked rug. To promote CBHI and publicise her rug designs, Lillian Burke relied on word of mouth, on handicraft colleagues like Wilfrid Bovey, and on journalists like Corolyn Cox or Lillian Von Qualen.

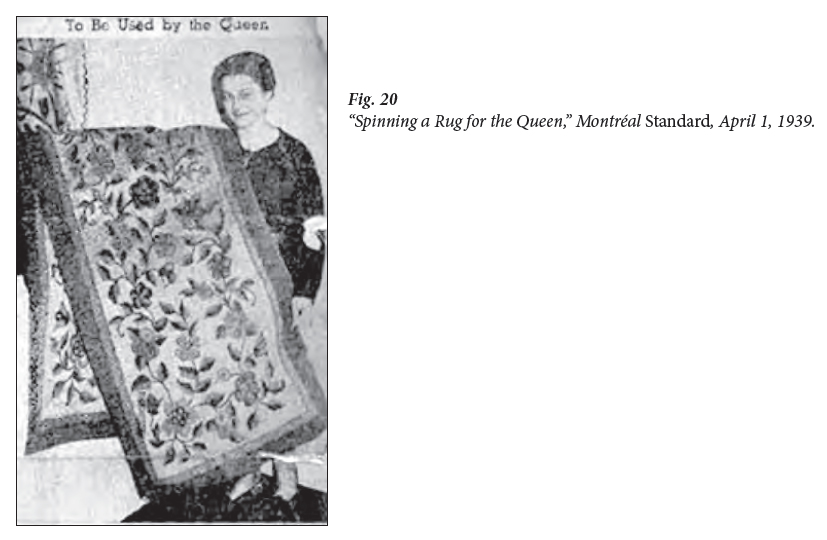

47 From 1935 onward, as the fame of the Chéticamp hooked rug spread, the number of periodical publications and books that mentioned it multiplied correspondingly. One lucky break was CBHI’s affiliate status in the Canadian Handicraft Guild, which ensured that Chéticamp rugs were sold in the Guild’s craft shop on Peel Street in Montréal, and at the Canadian National Exhibition in Toronto. It was at the CNE that CBHI scored its biggest publicity coup. Lady Tweedsmuir (1882-1977), wife of the governor general of Canada, bought two Chéticamp carpets at the guild stand in the autumn of 1938. One of those carpets, it was revealed, was intended for the queen’s bedroom at Government House in anticipation of the 1939 royal tour of Canada (May 15-June 17, 1939). It was the first time a reigning monarch had ever visited Canada and the month-long tour electrified the entire country.

Display large image of Figure 20

Display large image of Figure 20 Display large image of Figure 21

Display large image of Figure 2148 Born into the highest reaches of the English aristocracy, Susan Buchan, Baroness Tweedsmuir, is remembered today for her energetic relief work as vicereine of Canada during the tough years of the Great Depression (1935-1940). Her library project involved gathering books in Eastern Canada for impoverished dustbowl communities in the West. In addition to her interest in literacy, Lady Tweedsmuir was a relentless supporter of Women’s Institutes and Canadian handicrafts, inaugurating local prizes for embroidery, quilting, knitting, and other domestic arts. The benevolent interest she took in the Chéticamp hooked rug was thus entirely in keeping with everything we know about her work in Canada.

49 There exist two photographs of the Chéticamp “Queen’s rug.” The photo reproduced in Fig. 20 was published in the Montréal Standard on April 1, 1939, a month and a half before their majesties docked at Québec City. In the photo, we see a long and narrow carpet that we can estimate measured 2.5 or 3 feet wide by 7 or 8 feet long (approx. 1 x 2.5 m).

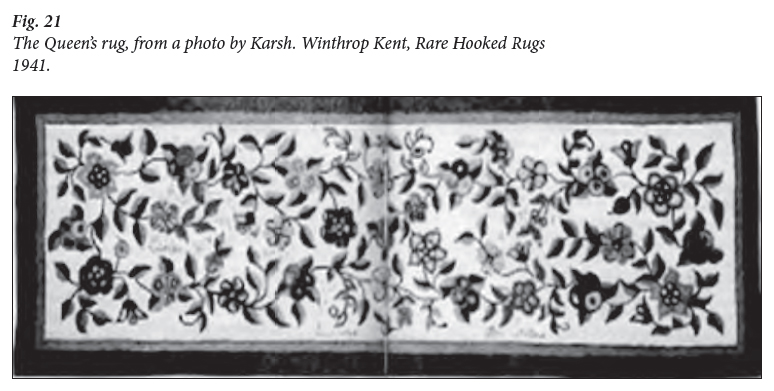

50 The second photograph of the “Queen’s rug” was taken by renowned Ottawa photographer Yousuf Karsh, on March 23, 1939. Karsh’s appointment book, held now in the National Library of Canada, records his visit to Rideau Hall under the heading ”Government House: Rug for their Majesty’s (sic) room.”10 That photograph was published three years later in Winthrop Kent’s Rare Hooked Rugs. A hand written cross beside the negative’s number (5391) suggests that Karsh himself removed it from its box. We can conjecture that the negative was sent to Winthrop Kent and not returned. Figure 21 is consequently a reproduction of Kent’s copy, not Karsh’s original.

51 To confuse matters slightly, Corolyn Cox published a second short article, titled “Rug for the Queen,” in the Christian Science Monitor on June 3, 1939. That article retails two errors of fact, suggesting that Ms. Cox did not view the rug in question. As a consequence, the journalist mistakenly claimed that it was presented to the queen by the women of Nova Scotia. In addition, Cox’s description of the royal carpet clearly references the Chéticamp Savonnerie, which, we know, she had seen and written up two years previously: “The hooked rug presented by Nova Scotian women to Queen Elizabeth on her trip to Canada is said to be the largest ever hooked” (Cox 1939: 15). The description of the queen’s rug in the Montréal Standard thus provides little more than a compilation of well-worked clichés:

Display large image of Figure 22

Display large image of Figure 2252 To be sure, Queen Elizabeth had more than a passing familiarity with William Morris, whose influence on the design is immediately evident. Karsh’s photograph brings to the fore Burke’s interpretation of Morris’s familiar botanical prints: trillium-shaped groupings of leaves and fruit, heavily shaded cinquefoil blossoms (with rosette centres), an assortment of rounded flowers, stylized tulips, and two-toned leaves alternating on sinewy “S” shaped branches. Unlike the two previously studied carpet designs, the “Queen’s rug” was not meant to be a literal transcription of natural forms. Burke’s floral motifs are formalized evocations of generic botanical arrangements in pastel greens, light pinks, yellows and soft blues, on a cream ground. Morris was known to adapt images of plants he found in 16th-century woodcuts, illuminated manuscripts, Islamic art, tapestries, and other textiles. Figure 22 is taken from one of his perennial sources, Treveris’s Grete Herbal (1526). Note how the shading of the leaves suggest Burke’s deconstructed, two-toned leaves in Figs. 20 and 21.

53 Where the Arts-and-Crafts style meets the French Baroque, unexpectedly perhaps, is in the similar use the two styles make of “S” shaped branches and graceful, intertwined leafy boughs. Lillian Burke’s version of the Arts-and-Crafts style is interesting in that, while implicitly acknowledging Morris’s inspiration, she avoids the great man’s tendency to crowd his designs with a Victorian profusion of vegetation. The result is an airier, restrained design contained within a strong panel-like border. Sadly, Burke’s hand-coloured design for the “Queen’s rug” has not come down to us. The carpet was not commissioned and we know nothing about its maker. And yet, because the decoration and maintenance of Rideau Hall fall under the jurisdiction of Public Works of Canada, we ought to be able to discover the carpet’s price. The bills for the 1939 royal visit are held at the National Archives of Canada in a file with the promising label of: “Ottawa, Ontario, Rideau Hall site and construction, carpets and rugs,” 1913-1949.11 Inexplicably, that file contains no mention of Lady Tweedsmuir’s purchase. Further research at Rideau Hall and with the National Capital Commission leads to the same disappointing dead end: there remains no trace today of the Chéticamp “Queen’s rug” in Canada’s royal collections. Fabienne Fusade, interpretation and exhibit planner at Rideau Hall, writes:

54 Nor is there any mention “of the rug having been presented to Queen Elizabeth” in the records of the 1939 royal tour housed at the Royal Archives, Windsor Castle.13 Inquiries with Canada’s leading antique dealers and in specialized magazines have not yet yielded any clues. Finally, we might consider that Lady Tweedsmuir bought the carpet with her own money, in which case she would have been entitled to keep it. Where can the “Queen’s rug” be today?

Conclusion

55 With the coming of war, Lillian Burke withdrew from Cape Breton Home Industries. It was, in more than one sense, the end of an era. In the mid-1940s she took up full-time employment as an occupational therapist with the New York Psychiatric Institute at Columbia University. At the time of her death in 1952, she was still in full-time employment at seventy-one years of age.

56 During the course of this essay, we have shown how Lillian Burke’s hooked rug designs aimed to raise a local craft to the level of a commercially viable decorative art. The three lost rugs we have studied represent only a tiny part of Burke’s design output; they nevertheless demonstrate the scope of her artistic vision. The carpets we have reconstructed emphatically confirm the outstanding quality of the Chéticamp hooked rug in the 1930s. All three are a tribute both to Burke’s teaching and to her workers’ willingness to learn new ideas of quality and design. The heroines of the Chéticamp hooked rug are, beyond doubt, Burke’s gifted workers. Theirs was a fruitful and rewarding partnership.

57 The vogue for hooked rugs in the 1920s and 1930s was a response to mass-produced textiles and an expression of pre-industrial nostalgia. Burke’s insistence on the use of soft faded colours was calculated to flatter that illusion by making new hooked rugs look like heirlooms. Her historically informed designs were part of the same general scheme, but, as we have seen, they transcended that scheme as well. Lillian Burke was no folk artist, if by “folk” we mean “un-schooled.” The latter-day charge that her teaching subverted traditional folk craft is a misreading of everything she stood for. An artist of culture and taste, Burke’s eclecticism was an expression of a lifetime of experience as a teacher, a handicraft practitioner, and student of fine art. Her receptive eye naturally combined the present and the past. Embracing art history, Burke renewed Cape Breton rug hooking and pushed the craft far beyond its traditional domestic expression. Even without examining the carpets she created, the photographs and watercolours we have studied demonstrate Burke’s complete mastery of the principles of textile design.

58 Successful on one level, Burke’s designs failed on another. The museum-class textiles she studied and adapted have in common their durability. Quality carpets—whether woven or pile, Eastern, European or American—can last for many decades, even centuries. Burke’s creations, by contrast, though beautifully conceived and executed, appear not to have stood the test of time. One evident problem was the designer’s reliance on rug hooking’s traditional burlap underpinning rather than a tougher cotton or linen foundation. By working with inexpensive burlap, Burke doomed her magnificent creations to slow deterioration. Added to this, the inevitable change in fashion meant that Burke’s carpets, at some point, began to look shabby and dated; outside of the Bell estate in Cape Breton, few examples of her work appear to have survived.

59 As knowledge of Burke’s art reaches academics, museum curators, dealers and collectors, we can hope that more of her work will come to light. In the meantime, the remnants of Burke’s life’s work are a humble confirmation of her status as an artist of taste and culture. Among the rug hooking’s grand ladies (and men), few can match the vitality, the inventiveness, and, let us say, the integrity of Miss Lillian Burke.

60 This essay is dedicated to the memory of Marie

Stella Bourgeois (1933-2015), Chéticamp artist in wool. With thanks to Michelle Guitard of the National Library of Canada, Jane Arnold of the Beaton Institute, Cape Breton University, Nancy Korber of the Archives Fairchild Tropical Botanic Gardens, Maryse Ménard of the Canadian Guild of Crafts, and finally, Pamela M. Clark, senior archivist at the Royal Archives, Windsor Castle. Marilyn O’Brien helped identify the birds in Burke’s paintings of wildfowl. Ian McKay, Martin Myers, Laurie Stanley-Blackwell and Peter M. Urbach made helpful comments and suggestions.