Articles

Memory in Action:

Clothing, Art, and Authenticity in Anthropological Dioramas (New York, 1900)

Abstract

Anthropological dioramas are museographic installations created in order to display artifacts. They are comprised of exotic material culture products as well as plaster sculptures, generated to show and contextualize the objects. In this article, the case of clothing made for the New York State Museum’s manikins is studied. I demonstrate how their authenticity is manufactured through certain practices, including embroidery, tanning, and dyeing. Paradoxically enough, replication techniques guarantee the object’s authenticity. Here, the proper origin of the thing matters less than the identity of those who manipulated the artifacts.

Résumé

Les dioramas anthropologiques sont des installations muséographiques. Ils réunissent les produits de cultures matérielles exotiques et des sculptures en plâtre conçus pour les mettre en contexte. En prenant l’exemple des vêtements portés par les mannequins du Musée de l’Etat de New York à Albany, je montre comment leur authenticité est fabriquée par un certain nombre de pratiques : broderies, teinture, tannage... Paradoxalement, des techniques de reproduction garantissent l’authenticité des costumes. Ce qui importe ici est moins l’origine des choses elles-mêmes que celle de ceux qui les manipulent.

1 In his 1989 book, The Real Thing, Miles Orvell paints a revealing picture of North American society in the 1900s: he depicts a world in the grips of a major epistemological shift—a world moving away from a tradition of imitation beholden to fakery and simulacra and into a system seeking to promote the authenticity of objects and experiences. Orvell suggests that, by the turn of the century, the counterfeit culture was fast waning, and society was undergoing a renewal, embracing authenticity, originality, and realness. While these values were strongly promoted through museums and the scientific milieu, a fondness for imitation would endure in the world of entertainment. According to Orvell, these two poles were not in contradiction. He argued that the two cultures could coexist, with each belonging to a separate intellectual universe: one valuing “popular” preference for copy and imitation, the other valuing scholarly notions of authenticity, particularly within the museum institution (Orvell 1989: 15).

2 The study of anthropological dioramas allows us to reinterpret the polarity between authenticity and imitation set forth by Orvell by demonstrating how techniques of reproduction can guarantee an object’s authenticity. Some of these techniques, replicating ancient actions and know-how, muddy the distinction between original and copy. Toward the end of the 19th century, German anthropologist Franz Boas popularized scenes known as dioramas or life-groups as a method to display objects from the collections of museums on the East Coast of the United States (Jacknis 1985, 2002; Jonaitis 1988). These dioramas, which had been observed at London’s Crystal Palace in 1851, and then at the Paris World’s Fair in 1878, presented anthropological specimens and life-sized figures representing indigenous people handling objects from various museum collections (Griffiths 2002). These displays harkened back to the tradition of natural history biotopes and to the cultures of tableaux vivants and human zoos (Haraway 1984-85; Bancel 2002; Quinn 2006; Lange 2006; Mungen 2006; Ames 2008). What did these scenes depict? What was the nature and provenance of the objects they displayed?

3 Some of the exhibited artifacts had been collected in the field, while others were constructed by the institution (Kirschenblatt-Gimblett 1998: 6). This article will focus on clothing worn by the Iroquois manikins in the New York State Museum in Albany, examining specifically what justifies their inclusion in these displays: in other words, what makes them anthropological and authentic. The use of plaster figures to display specimens necessitated costumes. Studying these costumes encourages an in-depth examination of the methods used in artifact production within the museum space, including modifications made to certain objects or contemporary materials (such as animal hide or fabric) before they could be integrated into various displays. In this example, the clothing is constructed, adapted, and made to conform to its current circumstances. Thus, the conditions under which these objects were created may be seen to determine their identity. The question of contact is at the heart of this process: the objects owe their very presence in the diorama to the context in which they were stitched, dyed, and embroidered. The archives of the New York State Museum (NYSM) in Albany and the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) in New York City yield insight into the fate of certain products of material culture, via analysis of the craftsmanship and processes involved in their creation.

A Nostalgia for Craftsmanship

4 The creation of the New York State Museum dioramas was supervised by anthropologist Arthur Parker between 1906 and 1917. The six dioramas form an ensemble depicting the First Nations that made up the Iroquois Confederacy, then based in present-day upstate New York. The six nations that composed the Confederacy were the Onondaga, Oneida, Seneca, Tuscacora, Mohawk, and Cayuga. The first life-group is the Horticulture Group (Fig. 1). It is dedicated to the cultivation of corn, beans, and squash, known as the “Three Sisters” of Iroquois agronomy (NYSM 1960). The choice to make this first diorama a scene depicting Native American agriculture was a deliberate one, allowing Parker to promote his vision of the region’s Native Americans as growers (Colwell-Chanthaphonh 2009). Here, the museum is endorsing a number of discoveries, and using the museum space to legitimize them.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

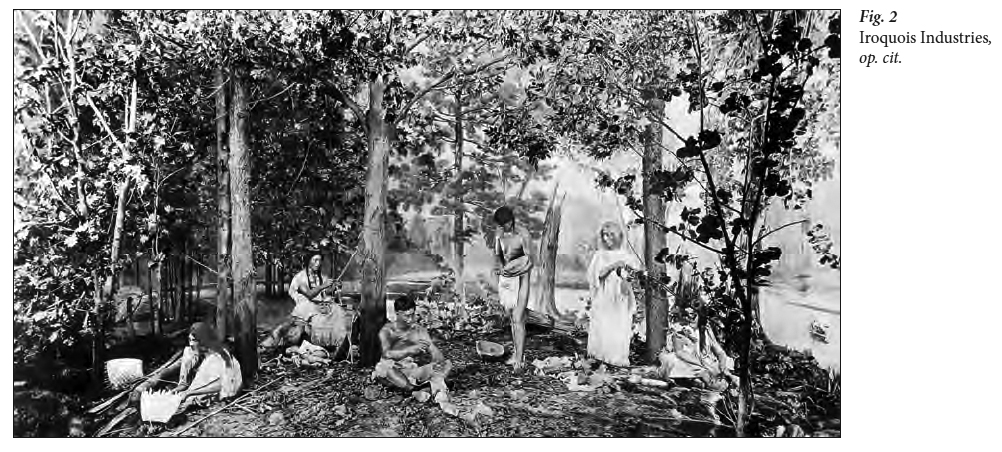

5 The second scene, titled Iroquois Industries, depicts figures engaged in “typical” activities: basket weaving, woodcarving, and pottery (see Fig. 2). These crafts were presented as characteristic of Native Americans, who were described as an entirely self-supporting people: “The native Indian made everything he used and he enjoyed doing it himself” (NYSM 1960). The question of craftsmanship thus takes center stage in these representations. At a time when the industrial boom had reached its peak and the Victorian epoch was on its way out, these scenes nostalgically recreated a forgotten time, when individual know-how and family economy still dominated (Jackson Lears 1981: 60-96; Dilworth 1996: 125-72; Hutchinson 2009: 28-108).

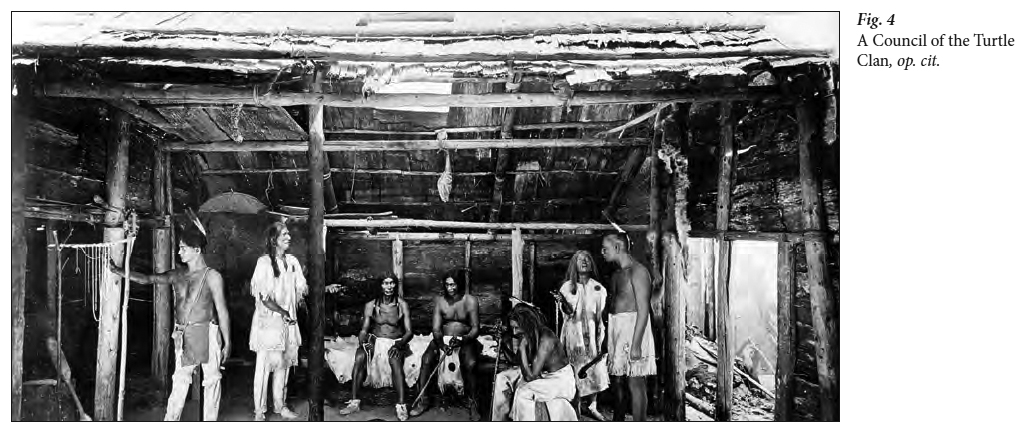

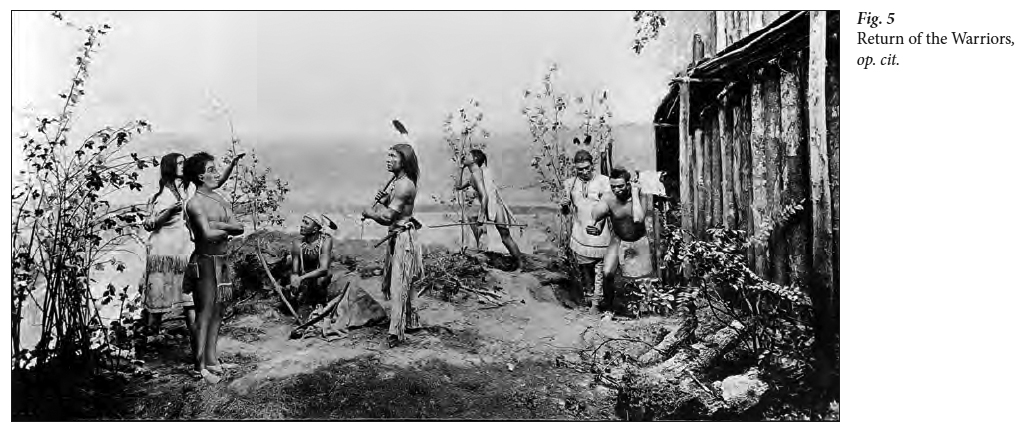

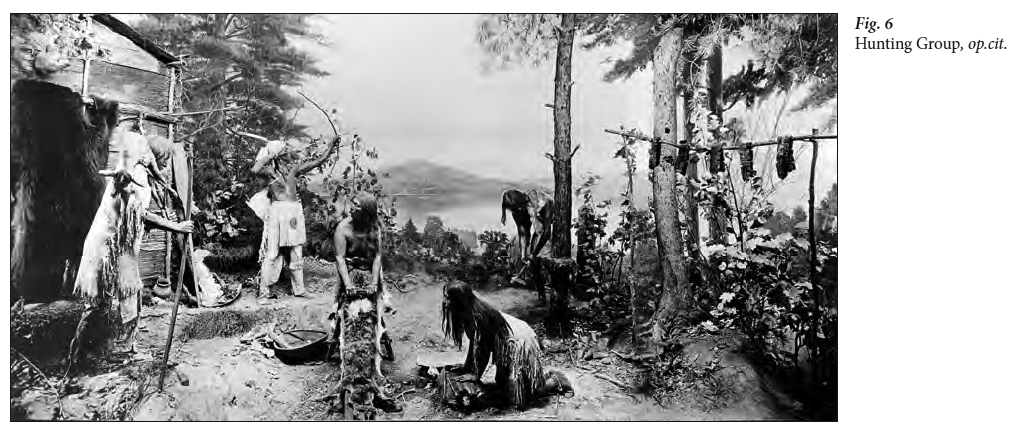

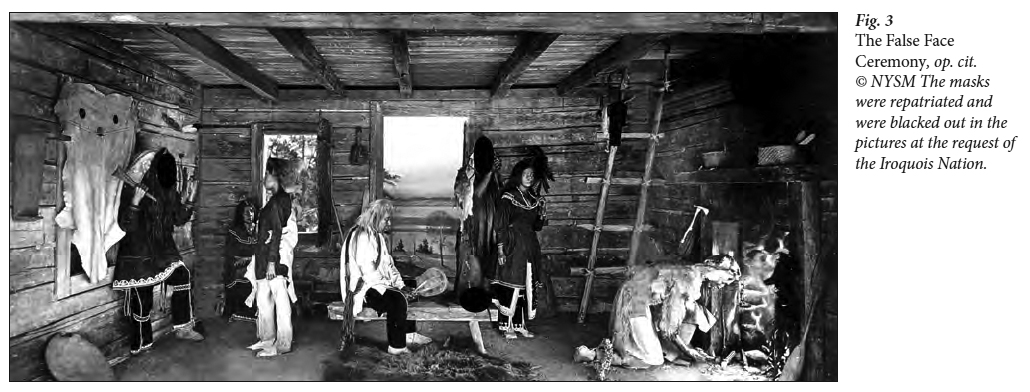

6 The third group depicts a re-enactment of the False Face Ceremony (Fig. 3). This healing ritual took place during the Iroquois New Year, when disease and evil spirits were driven out of the village. The purpose of this scene is to highlight traditional societies’ use of new materials, such as cotton, which slowly started to replace animal hides. Compounding the argument, Parker added glass beads to the traditional decorative elements. The fourth group recreates the Council of the Turtle Clan (Fig. 4). The clan chiefs are gathered in a wooden room with Wampum belts around their waist, conferring upon them the authority to speak during the ceremony. The fifth group depicts the Return of the Warriors. Mohawk warriors return to the village with two Mohican prisoners and a meeting is called to decide the two men’s fates (Fig. 5). The last diorama is called Hunters’ Group (Fig. 6). A Seneca family is working outside of the house, each member of the tribe engaged in a specific task. The iconography of the diorama may be contextualized in regard to broader interests and interrogations shared by anthropologists, intellectuals, workers, and reformers. The division of labour was a lively debate at the time: in this context, Native American tribes were often perceived as promoting a decent and potentially inspiring vision of divided labor based on a naturalized gender difference. In his book dedicated to “all good women, dead or alive,” the anthropologist Otis Mason stated: “Division of labour began with the invention of fire-making, and it was a division of labour based upon sex” (Mason 1899: 15). This is the kind of vision that these particular dioramas promoted.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3

Authentic vs. Genuine

7 In December 1915, Parker wrote a note to John Mason Clarke, then director of the Albany Museum, informing him of his progress building the dioramas. Parker listed the objects necessary to finalize one of the displays: benches for the house; bear, turtle, and wolf sculptures; corn; wooden posts; tobacco; twenty pairs of moccasins; clothing; and a moulding of a baby’s face (Parker 1915, file 3). The word “article” was used here to unify all these objects—“article” as opposed to the words “object” or “artwork,” both of which link back to the consumer world (Leach 1993: 40-70). All of these articles were key to the completion of the scene in progress, and Parker made a commitment to personally gather as many of the objects as he could.

8 In situations where it is impossible to gather all the objects necessary for display, anthropologists will sometimes decide to have them made. A glance at the inventory generated during the dismantling of the Albany groups testifies to the diversity of the articles produced. One list enumerates the objects included in the Council of Turtle Clan group: details are provided for each artifact, whether a specimen from the collection or a custom-made item. On the one hand, the list contains a high number of valuable artifacts procured in the field, such as the Iroquois Wampum belts. On the other hand, there is also much detailed description of the clothing specifically created for this group, including the materials used: the pants were made from hides; the moccasins from simulated deerskin adorned with decorative painting; the sash of embroidered animal skin. Some of the objects, such as the moccasins, are explicitly described as “genuine” (Clarke: 1935).

9 In the 1930s, Noah Clarke, an archeologist at the New York State Museum and son of the museum’s former director, penned a history of the anthropological dioramas of the museum. Clarke wrote about the groups: “The virtue of such groups is that costumes, ornaments, implements and utensils are all properly correlated and their uses shown” (1935). His central argument was that all such elements were “genuine”:

10 In this account Clarke repeated word-for-word a description first written by Arthur Parker, in which every element was described as genuine. The painting alone escaped this classification, being obviously a representation. However, it was deemed no less “accurate” a depiction of, and “intimately connected” to, the history of the First Nations (1935). Here, the objects’ authenticity does not hinge on their age or even on their provenance, but rather on the various links that bind them to the land and to the Native people.

11 As we have seen in my previous examples, the word genuine was often favoured by anthropologists to qualify such materials. Despite its apparent parity with the word “authentic,” the two terms vary on an etymological level. While the word “authentic” is bound up in the idea of authority conferred by a master, the word “genuine” has a different root: according to the Oxford Dictionary, its root is found in an ancient Roman custom, wherein a newborn was placed on his father’s knee (genu in Latin) to seal the filial bond through bodily contact (Oxford English Dictionary 2014). Thus, the child’s identity was confirmed through gesture, or physical action. Similarly, for costumes on display in the dioramas, touch and handling were key components of authenticity.

Manufacturing Authenticity in the Museum

12 Bringing together different objects of varying provenance was a common practice across museums in North America and Europe in the 1900s. Period Rooms, several of which may still be seen at the Metropolitan Museum of New York, were representative of this trend (Anonymous 1916). According to the Met’s former director, Philippe de Montebello, these reconstructions embody varying degrees of authenticity. Montebello describes the room used to showcase Robert Campin’s Triptych in The Cloisters, in North Manhattan, as a characteristic case: the room itself is modelled on the canvas of Campin’s Annunciation, which hangs on the wall. Yet despite the room’s artificial dimension, Montebello describes a deeply emotional experience, insisting heavily upon the fact that every displayed object is original.

13 The Met’s period rooms place an emphasis on the authenticity of the objects on display. But what constitutes this authenticity? What arguments are put forth to qualify these artifacts as authentic? Susan Vogel, the former conservator of African art at the Metropolitan Museum, provides an interesting definition: “The fact of having been made by Africans is not sufficient to make an object ‘real’; the consensus is that only a work made for traditional use and actually used can be considered authentic” (1988: 4).1 Vogel, echoing Austrian art historian Aloïs Riegl’s “age-value” argument, cites an object’s age as an index of its “purity,” vis-à-vis colonial interference in traditional life and the corrupting presence of foreigners on Native land. She stresses the importance of use (again, echoing Riegl’s theories on “use-value”), offering the example of an object purchased by a colonial administrator in the 19th century. She argues that this object, which was never handled in a traditional context, would not be desirable to a collector, beautiful and rare as it may be:

Hence, if they do not fulfill both requirements—created by Native peoples and used by Native peoples—objects may be rejected.

14 Vogel does offer that there exists a spectrum from fake to authentic. The study of clothing in dioramas around 1900 shows that the question was constantly renegotiated on a case-by-case basis, according to supply and demand, as well as the artifacts themselves. The categories of age and use were not central to the examples I am about to give: rather, geographical site and methods of production, as well as the link to the culture of manufacture, were key determinants of authenticity.

The Iroquois Method

15 The New York State Museum had different ways of procuring the specimens it displayed in its dioramas. The first method was for Parker to travel to the field himself to collect artifacts. If he were unable to go in person, he would use intermediaries on the reservations, sometimes members of his own family (his father was Seneca). Finally, he acquired some of the base materials used in the production of costumes through merchants and traders. In June 1909, he decided to obtain animal skins via a New York retailer:

He purchased four deer hides to be used in the production of clothing for the figures: “These skins are to be used for making one or two articles of clothing which we can not furnish from specimens in our Museum collection and will be useful afterwards as furnishing for the casts” (1909, file 5).

16 Before he could include them in the display, however, the materials had to undergo a series of transformations. First, the skins had to be “tanned by the Iroquois method,” then “aged” in accordance with the group’s other elements (1909, file 5). By December 1909, Parker had apparently still not reached his goal: “I should like to get these skins now and have them worked up and the costumes properly aged” (1909, file 5). The aged and worn appearance of a garment is prized over its actual age. It is not enough to simply buy artifacts or have them custom-made—the materials themselves need to be adapted in order to achieve an overall aesthetic. The modifications of these materials become an index of their genuineness and, as a result, their legitimacy within the display apparatus—despite the materials having never been used outside of a museum context. Aging and tanning, but also dyeing or embroidery: these techniques embed the clothes in an assumed Native historical narrative and aesthetic. The genuineness of certain specimens is thus created within the museum space. They are authentic copies, real reproductions. Their genuineness, mirroring the origins of the word, is proven by contact.

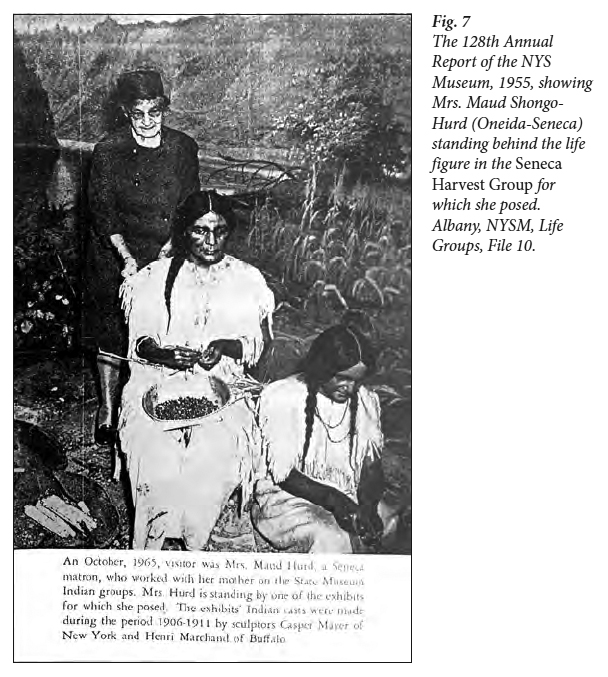

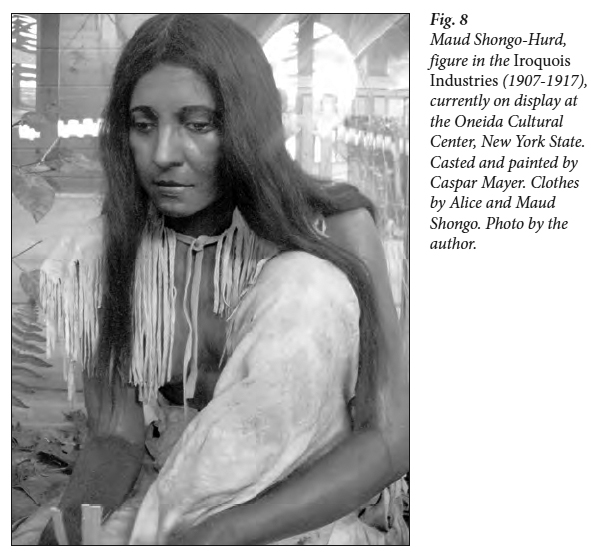

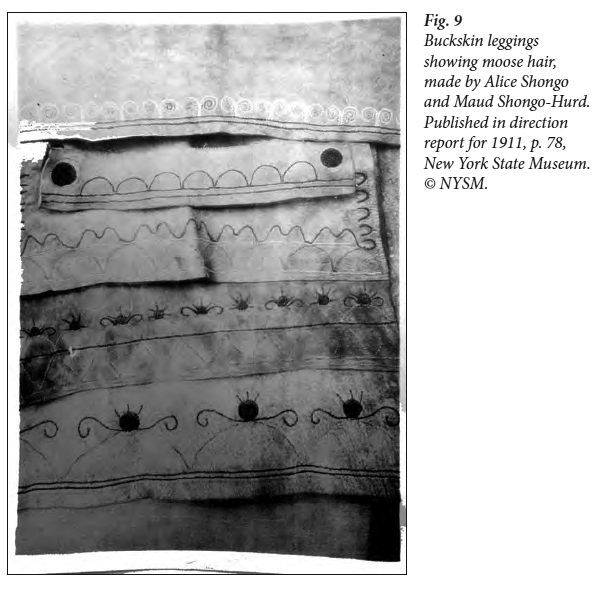

17 In January of 1911, Arthur Parker wrote a letter to the patron subsidizing his dioramas. He told her two Seneca women were tasked with embroidering skins for clothing: “A number of Seneca women are engaged in embroidering the skin costumes for the life figures, as it is now no longer possible to get the old costumes and indeed there are few women left who know how to do the embroidering in moose hair and porcupine quills” (Parker 1911, file 6). Mrs. Alice Shongo and her daughter Maud, later Shongo-Hurd, were the women hired to do this work (Fig. 7). They were also life-casted and integrated as manikins inside the diorama (Fig. 8). Parker insisted that few women still knew how to embroider with moose hair and porcupine quills (Fig. 9). Here again, we see that the preservation of craft is key:

Fear of the looming extinction of Native peoples was compounded by the concern—widespread at the start of the century—over vanishing craftsmanship. The display of these garments, hand-embroidered by women on the reservation, is legitimized not by the age or worn appearance of the artifacts, but rather by the traditional methods employed in their production. Thus, the reproduction of gestures, techniques, and objects is not decreasing the legitimacy or authenticity of the thing: on the contrary, it is giving to the thing its value, as long as it is reproduced in proper conditions, including intimate contact with indigenous bodies and traditions.

Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 9

Display large image of Figure 9

Skill, Soil, and Blood

18 However, the notion of a skill perpetuated by women on the reservation is in fact contradicted by sources. Indeed, certain methods that were no longer practiced had to be resuscitated for the project. In this way, museums became repositories for traditional handicraft. In one of his letters to the seamstresses, Arthur Parker wrote that the technique of moose hair embroidery was easy, and could be picked up from examination of the models on display at the museum: “Moose hair embroidery is not difficult. We have samples of the work which plainly show the method” (1910, file 6). Such situations necessitated experiment, often using materials sent as reference by the institution to the production site. In October 1910, Parker sent Mrs. Shongo and her daughter various samples of hides and moose hair, that they might experiment with different techniques: “Under separate cover I am sending you some buckskin and quills together with a little moose hair. This is for Mrs. Shongo’s experiments” (1910, file 6).

19 There are also examples of technical traditions being preserved outside of the community. At one stage, Parker attempted to have some clothing dyed using an ancient recipe concocted from red berries. He was aware of a group of French women living in Canada, skilled in this method: “There are many French women in Canada, just north of us, who know how to do the work about which I am speaking but I much prefer to have an Indian woman do it” (Parker 1910, file 6). His preference was to put an Iroquois woman in charge of the process. Arthur Parker was explicit: moreso than skill and technique, it was the ethnicity of the craftsperson overseeing the task that justified the products’ inclusion in the dioramas. Parker preferred to hire a Native American ignorant of the technique over a French woman who had mastered it. The craftsperson’s ethnicity thus became a determinant in the object’s authentication process.

20 Finally, the site of production was another determining factor: from 1912 onward, Seneca women made the clothes on the reservation. This was a testament to Arthur Parker’s strong position on the subject; a position he argued frequently to his supervisor. In 1910, an Iroquois woman called Julia Crouse, living in Versailles, New York, travelled to Albany to work on the costumes. She was paid 2 dollars a day, which was the same wage paid to live models. On December 8th, 1911, Parker announced the construction of the Oneida and Onondaga groups, both requiring the creation of a dozen costumes. He suggested outsourcing the work to the women he had previously trained, so that it might be undertaken on the reservation (Parker 1911, file 6). The museum director, John Clarke, raised concerns over the project, quoting past negative experiences. Despite the lower cost of outsourcing the work, which required no per diem or accommodation, Clarke worried that a “climate of irresponsibility” added to a “lack of supervision” would jeopardize the work. Parker refused to budge. In a letter written in 1912, Clarke suggested once again that a fee be negotiated for the finished product, as opposed to an hourly or daily rate (1912, file 6). Parker rejected his supervisor’s motion, instead suggesting an hourly rate for Mrs. Shongo, arguing that he could cross-reference her timesheet against the hours charged for her previous work (Parker 1912, file 6).

Objects as Archives

21 Despite the original craft having been lost and needing to be relearned, Parker insisted the only people qualified to produce the garments were Native American women, preferably on the reservation, as authenticity was inherent in their labour. The contextual authenticity of an object depends less on its usage than on the maker’s ethnicity and on the site of production. Having served its purpose in the context for which it was designed does not authenticate an object here. Rather, authenticity is derived from its relation with a particular craft and the determining factor of its geography. In this light, the authenticity of materials is also secondary. Certain products used in the creation of garments were neither found nor produced on the reservation, but rather sent there by Parker himself (Parker 1912, file 9). Stitched, embroidered, dyed—not only according to Native American methods, but also by Native Americans—the objects in the dioramas acquired specific identity through their contact with the Native American and her living environment.

22 Finally, the clothing serves as an archive of traditional Native American handicraft. The objects in the museum are held up as containers of memory: repositories of craftsmanship and past techniques. Parker presented the entire dioramas as sites of memory, preserving not only the objects, but also the techniques by which they were made: “I want this to be—and it should be—the paramount display of the Iroquois culture and the tangible record of the Iroquois Confederacy” (Parker 1911, file 34). These skills and craftsmanship were preserved on two levels: on the one hand, the displayed clothing was the result of a re-enactment, showcasing traditional production methods; on the other hand, the mimetic iconography of the dioramas recorded and stored craft processes. In their capacity as iconographic and scientific projects, the dioramas not only intend to preserve the image of a lost craft, but their components embody a link to a vanished skill and time. They were meant to be, on various scales, a monumental archive of native arts and crafts.

“This is not an Artifact”

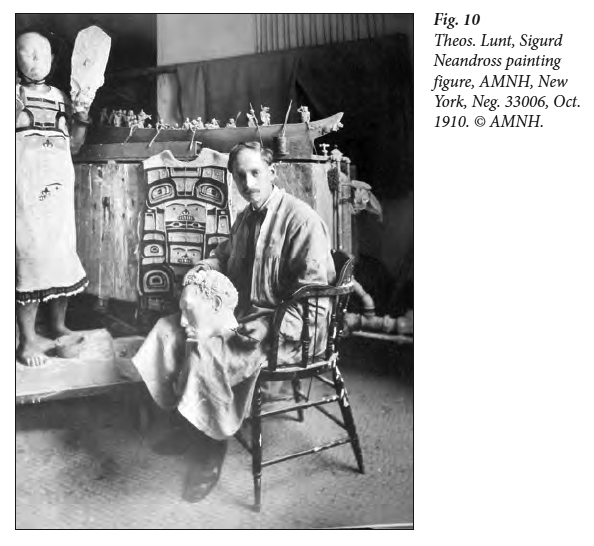

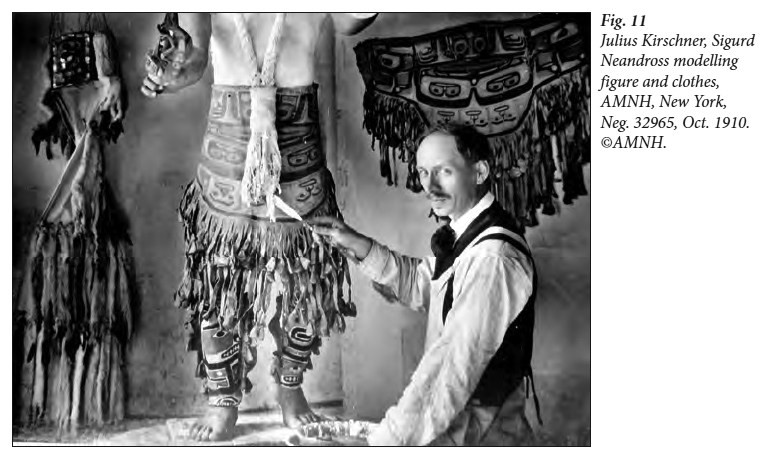

23 Not all dioramas display clothing produced according to such methods. Some garments were in fact produced by artists employed by the institution. An example of this is the plaster clothing made by Danish sculptor Sigurd Neandross for the New York Museum of Natural History (Freed 2012: 76) (Fig. 10).3 Neandross produced costumes using a textile base dipped in liquid plaster and affixed to the sculpture (Fig. 11). The garments were made to attire the models seated in the Big Haida Canoe, an enormous canoe displayed variously throughout the museum, and today hung from the entrance ceiling, minus the plaster occupants.

Display large image of Figure 10

Display large image of Figure 10

Display large image of Figure 11

Display large image of Figure 11

24 The sculptor believed that plaster on its own was too brittle to guarantee good reproduction of clothing and objects. He described how the fabrics and the burlap were first soaked in plaster and glue, before being adorned with the “appropriate imagery.”4 No original element figured in this production process. The objective here was to compensate for the lack of genuine Native American costumes by creating an imitation. Anthropological prints and specimens were nonetheless used as a starting point in the production of the models and in the painting of the mouldings (Coffee 1991). The sculptor also suggested other alternatives; the cover of the Chilkat chief, for example, was a knitted, custom-made item. Here, reproduction was justified through the argument of conservation. Faced with the frailty of objects involved in the display—furs, woods, textiles, etc.—Neandross argued that a replica provided an effective way to preserve the original. All the displayed objects were thus copies, made by the sculptor. He stressed that the work had both artistic and scientific value:

According to Neandross, the work required significant artistic skill. The level of difficulty was increased by the scientific and memorial implications of the assignment, which was required to capture and record with precision the physical traits of Native Americans.

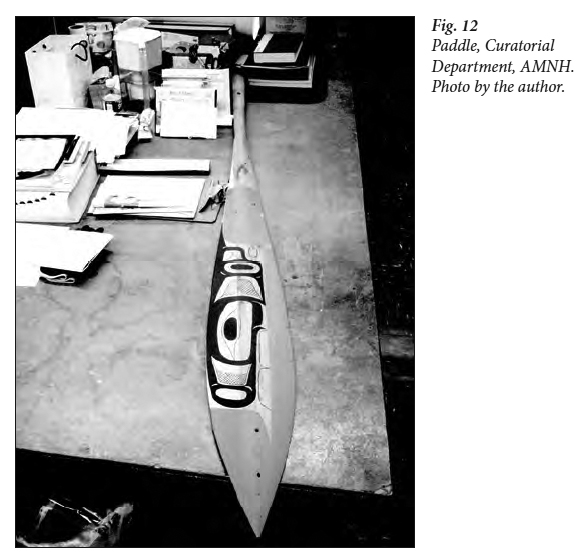

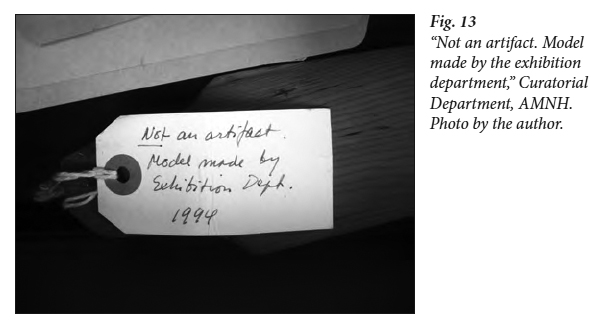

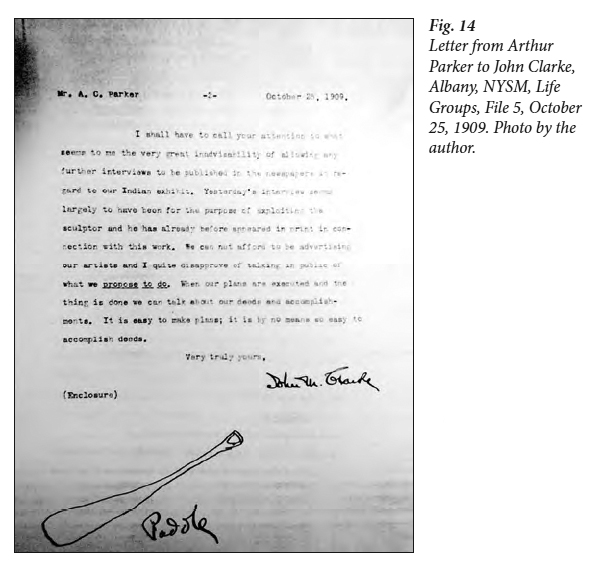

25 The plaster costumes made by Neandross are not the only custom-made museum artifacts from the 20th century. Another example of an item produced solely for the dioramas is a paddle, found by case in a curatorial office of the American Museum of Natural History (Fig. 12). The paddle was made in the 1990s for the Great Haida Canoe. To prevent it from entering the collection, it was labelled thus: “This is not an artifact” (Fig. 13). Anthropologists are often faced with ambiguous experiences and societies in flux, and the originality of artifacts is seldom guaranteed. Such grey areas have colored the discipline since its beginnings. On October 25, 1909, Arthur Parker wrote to John Clarke that he was investigating a paddle that might interest him. He included a drawing of the paddle, but noted the hole in the handle made him wonder whether the paddle was not an “anthropological fake” (1909, file 5) (Fig. 14).

Display large image of Figure 13

Display large image of Figure 13

Display large image of Figure 14

Display large image of Figure 14

26 The clothes fabricated by Sigurd Neandross were not considered authentic specimens. Yet the presence of artists in the Museum of Natural History was not limited to those involved in the fabrication of dioramas—nor was the imitation of ethnographic clothing. The Museum of Natural History in New York had ambitious views indeed, as Ann Marguerite Tartsinis recently demonstrated (Tartsinis 2013). Since 1903, the Natural History Museum in New York encouraged the study of Native American patterns from its collection. Designers spent time in contact with the artifacts, seeking inspiration from specific ethnographic forms. In this context, the imitation of clothes became an important trend. Fashion designers invested in the museum galleries even before the First World War. Native American clothes were not only studied for museum or display purposes: their study was encouraged as a means of revitalizing contemporary design. This process was intended to stimulate the national production and to create a visual and industrial basis for a real American design. Beginning in 1915, the Museum of Natural History in New York increased its involvement in promoting the study of its collection, culminating with the “Exhibition of Industrial Art in Textiles and Costumes,” held in the American Museum of Natural History in 1919.

Conclusion

27 The clothing on display in the Albany and New York dioramas invites us to question notions of authenticity in the museum around 1900. Thus the question asked by Orvell can be rephrased. The craft and intention behind costume production takes precedence over the question of authenticity. Various people had a hand in the production of the clothes on display: Native Americans, who cut, assembled, dyed, and mended them; the anthropologists, who removed them from their original milieu; and the artists, who transformed, adapted, or recreated them. These clothes, products of artisan craftsmanship, are abstractly defined by a series of practices. Adapted, stitched, and soaked, the objects acquire meaning through a series of transformative processes that confer their authenticity as products of material culture.

28 The actions that serve to make them are not devoid of meaning. The sites and modes of their production lend a historical narrative. They are realized according to traditional skills, via “typical methods,” often craftspersons in the communities represented in the diorama. In this context, the traditional aspect of production and reproduction takes precedence over the provenance of materials. These practices appear as timeless marks of legitimacy; indeed, no matter that these skins were tanned by Iroquois from centuries ago, what counts is the method of production and the circumstances of labour. To guarantee the object’s anthropological legitimacy, it is vital that the hand that made it be Iroquois. Craftsmanship as a reservoir of memory transforms these clothes, which are in turn presented as sites of this memory and an archival record of technical know-how.

29 On one hand, the clothing made for displays is rendered authentic by contact with Native people and the (geographic) site of production. On the other hand, the scenes animate the usage of the objects, mimetically replacing with plaster figures the absent bodies that once handled them. The question of contact and of physical touch is at the heart of these installations. Beyond their costumes, the models themselves are embedded in the anthropological project because of their impressionistic quality. What confers authenticity is the fact that they are castings—direct and unmediated (Didi-Huberman 2008). Resemblance and authenticity are born of that intimate contact. The bodies of the Native Americans breathe life into the clothing and the plaster models, reconfiguring the very nature of the artifacts and justifying their presence within the institution.

30 Finally, the call for genuineness went far beyond the museum context at that time. In 1924, in a text entitled “Culture, Genuine and Spurious,” the anthropologist Edward Sapir affirmed the genuineness of the Native American society, as opposed to the artificiality of contemporary euro-American culture (Sapir 1924). Indeed, in a time of search for a national identity as well as for a morally-grounded society, the genuineness of the Native American society was often praised as a model. Forms, design, and patterns also played a role in this regeneration process. The imitation and replication of Native American artifacts became in the United States one of the most important ways to develop a design culture and a textile industry properly “American.” As Elizabeth Hutchinson has demonstrated, the collection, study, and imitation of Native American handicraft and design became part of a major project to revitalize society and created the condition of emergence of an American modernity (2009).

I would like to thank Meredith Younge for her help throughout my research, as well as Yaëlle Biro, Manuel Charpy and Merel van Tilburg.