Research Note / Note de recherche

Hay Barracks in Newfoundland

1 Hay barracks are a vanished piece of Newfoundland’s history, a very specific type of vernacular agricultural architecture that is no longer seen in the cultivated fields of the province. Like other aspects of vernacular agricultural outbuildings such as root cellars, equipment sheds or animal pens, hay barracks have rarely been seen as “historic” properties in their own right. In Canada, outbuildings have been protected generally where they exist as part of an historic cluster. One small-scale example of this can be seen in the Shano/Le Shane Property Registered Heritage Structure, Lower Island Cove, Newfoundland, designated as a Registered Heritage Structure by the Heritage Foundation of Newfoundland and Labrador in 2006. In addition to the main house, the designation includes a root cellar, well house, shed and outhouse (Canada’s Historic Places 2014b). Another larger scale example is the Duke of Sutherland Site Complex, Brooks, Alberta, designated a Provincial Historic Resource by the Province of Alberta in 2000. The designation includes the historic farm estate, but also traces of the irrigation ditches, a generator building, an outhouse, a barn and a pump house (Canada’s Historic Places 2014a).

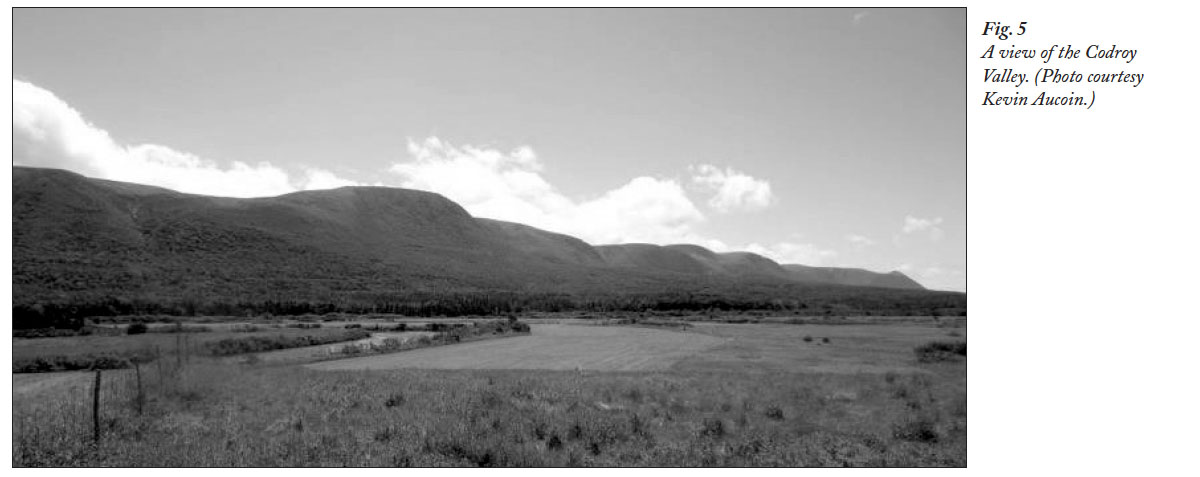

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 12 Rarely, however, are vernacular outbuildings considered worthy of such official recognition, though collectively they are an incredible (and rapidly vanishing) resource. Buildings like this are invaluable in how they demonstrate the link between built heritage and our intangible cultural heritage. Simple working buildings provide a focal point for the study of how traditional and informal knowledge is passed along, adapted and sometimes abandoned as culture and society shifts. This research note takes one example of a vernacular structure, the hay barrack, and shows how it can be a stepping stone for research on local agricultural traditions. It is an attempt to present what is known about hay barracks in Newfoundland; to give a sense of their origin, history, diffusion and use; and to document their decline and eventual disappearance from the cultural landscape of the province.

What is a Hay Barrack?

3 The Dictionary of Newfoundland English defines a hay barrack as a “structure consisting of four posts and a movable roof, designed to protect hay from rain and snow” (see, as an example, Fig. 1; Story 1990). It goes on to note that such a structure

4 “There’s a lot of people don’t know what a hay barrack is,” reminisced Goulds-area farmer Leonard Ruby, as part of the Heritage Foundation of Newfoundland and Labrador’s Seeds to Supper Folklife Festival in 2011:

Leonard Ruby’s description of a basic hay barrack is fairly representative of those found in Newfoundland and elsewhere. Usually constructed with four (sometimes five) poles, with a roof that raised and lowered, hay barracks saw some local and regional variations depending upon the whims, needs and construction skills of the farmers and labourers who created them.

5 While the number of poles could vary, the defining feature of the barrack was its movable roof:

A letter dated November 13, 1787, and written by Mrs. Mary Capner from Hunterdon County, New Jersey, to relatives in England, includes this descriptive note about hay barracks:

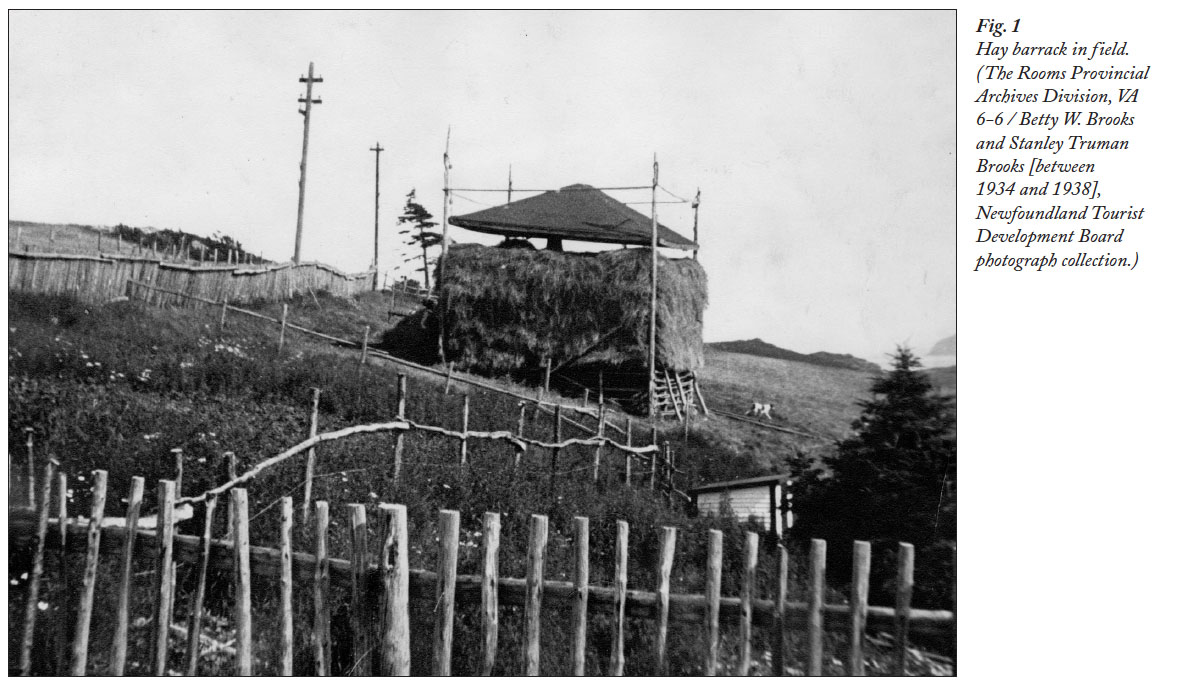

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2Origins of the Hay Barrack

6 St. John’s farmer Leonard Ruby’s assertion that the hay barrack originated in Holland may be correct. In the Netherlands, the structure was primarily known as a hooiberg, or hay mountain (Fig. 2), though many other regional names exist (Noble 1985: 107, 111). Some of the earliest archaeological examples, with three and five posts, were excavated as part of a late Bronze Age farm at Zwolle-Ittersumerbroek, Netherlands (Zimmerman 1992: 37). Noble notes that

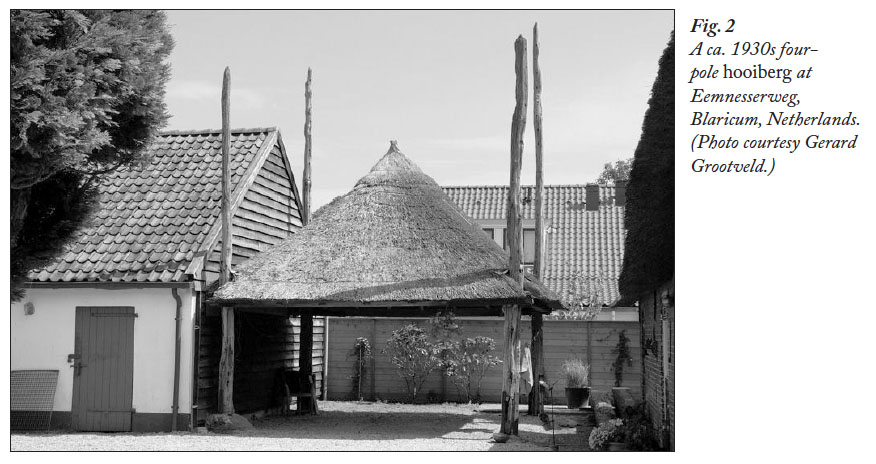

Rembrandt even made an etching of one in 1650. Hooiberg-like structures spread throughout the Netherlands and beyond, even as far as the Ukraine, possibly introduced by Dutch or German Mennonites (Noble 1985: 114). Local historian Gerard Grootveld has documented a number of hooiberg structures in and around the community of Blaricum, Netherlands, including three-pole, four-pole and five-pole variants (see Fig. 3).

Display large image of Figure 3

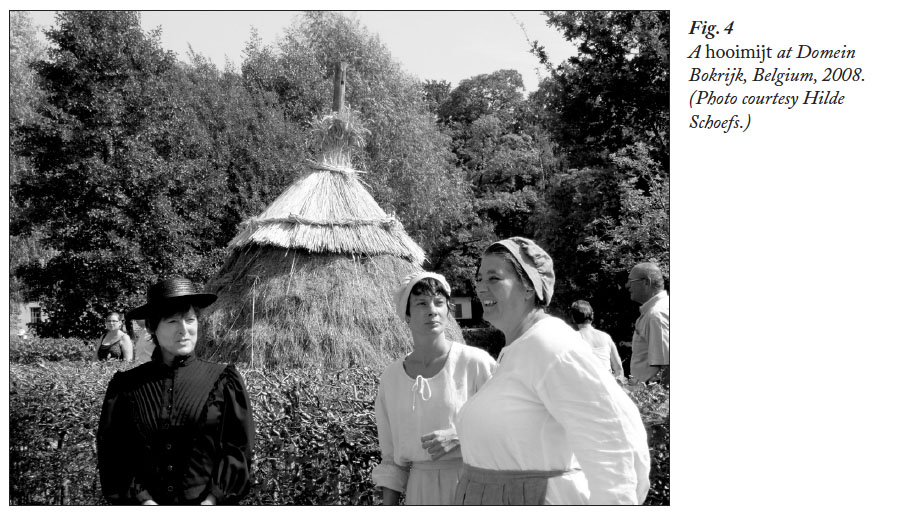

Display large image of Figure 37 In Flanders, there are numerous terms to describe similar hay storage structures. Hilde Schoefs, conservator at the Domein Bokrijk Open Air Museum, notes,

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 48 By 1698, at a time when the use of similar structures in the British Isles may have already been in decline (Airs 1983: 51), Dutch pioneers were headed west across the Atlantic. The Dutch introduced hay barracks to New Jersey in the late 17th and early 18th centuries (Wacker 1973: 36). By 1730, Dutch hay barracks had been adopted by other ethnic groups in New Jersey (Wacker 1973: 41), and the technology soon spread. In the Pennsylvania Dutch area, the local term shutt-sheier has been documented as early as 1756 (Shoemaker 1958: 3). From there, the humble hay barrack spread to Massachusetts, Virginia, Maryland, Ohio, Iowa, Illinois, Wisconsin, New York, Rhode Island, Prince Edward Island, and southeastern Manitoba (Noble and Cleek 1995: 162). Hay barracks also spread to certain areas of Kansas, perhaps introduced by Mennonite and German Catholic farmers (Hoy 1990: 117).

9 In Newfoundland, the term for such structures was most often “hay barrack” though the same roofed structure was sometimes called a “stack” in the Codroy Valley. The term “barrack” varied in other regions: “No shed owner in Kansas that I have talked to has ever heard the term ‘hay barrack’” writes Hoy (1990: 117). Instead, Kansas farmers predominantly used the term “hay roof,” though some used “hay shed,” “pole shed,” “alfalfa shed” or “hay cover.” Farmer John Lies of Andale, Kansas, referred to his hay barrack as the “lily pad”—“because it floats up and down and because it is cool” (Hoy 1990: 121). In the British Islands, similar structures were known as “helms” (Zimmerman 1992: 34) but were also possibly known as “hovels” (see Airs 1983; Dyer 1984) or “belfrys” (see Needham 1984), and, in one English 17th-century nod to possible origins, a “Dutch barne” (Airs 1983: 51). The phrase “Dutch barn” continues in the British farming tradition, to refer to a barn with a roof and open sides, sometimes called a pole barn, though generally with a fixed roof.

Advantages of the Hay Barrack

10 It has been argued that the popularity of the structure was probably due to the fact that a barrack could be built “quickly, cheaply, and easily, and could be used to house both stock and grain or hay. In short, it was an ideal structure for the pioneer agriculturalist” (Wacker 1973: 41).

11 A structure that combined both simple construction and an extended life for hay made it popular with farmers. In an interview with farmer Marcellus Englebrecht of Andale, Kansas, researcher James Hoy notes that Englebrecht “says that a hay roof is the cheapest possible shelter for a hundred tons of hay, and he showed me some bales that had been in his shed for ten years, the hay still bright” (1990: 121).

12 At some point, the concept of this practical and inexpensive structure hopped the Gulf of St. Lawrence and was introduced into the vernacular architecture of Newfoundland. It was a firm part of regional agricultural traditions surrounding St. John’s on the east coast of the island, and in the Codroy Valley on the west by the middle of the 19th century. In the Codroy Valley of Newfoundland’s west coast, farmers found that the hay barrack was cheap and easy to build, and, as late as 1983, there were at least ten hay barracks still in use in the region (MacKinnon 2002: 28). MacKinnon explains the hay barrack’s advantages:

Codroy Valley Hay Barracks

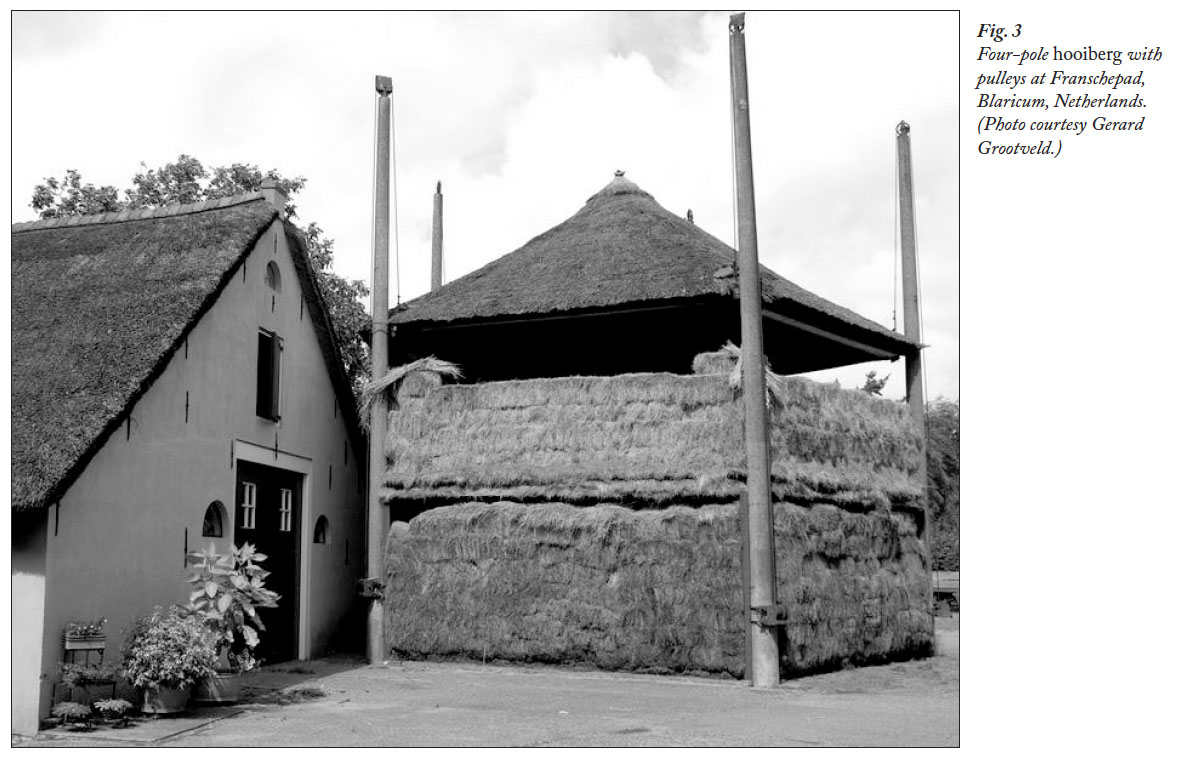

13 The Codroy Valley is a glacial valley formed in the Anguille Mountains, a sub-range of the Long Range Mountains that run along Newfoundland’s southwest coast (see Fig. 5). A particularly fertile area for agriculture, European settlers had begun to farm the area by the early 1800s. Many Codroy Valley settlers were of Scottish origin, arriving in Newfoundland via earlier settlements in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia. They brought with them knowledge of farming culture, and of hay barracks, which were used extensively in Cape Breton, particularly in the Margaree River district (MacKinnon 2002: 29).

14 Kevin Aucoin’s family provides a good example of this transfer of Cape Breton agricultural knowledge to Newfoundland. Aucoin was born in 1941 and grew up in the Codroy Valley in the small community of Tompkins. The son of William and Dorothy Aucoin, his grandfather William came from Cape Breton to Newfoundland in approximately 1880 at the age of sixteen. Like other farmers in the valley, the Aucoins made use of hay barracks.

15 “In our region everybody had a farm—we all grew up on farms in the community and I would say pretty well every farm family had one of these—very very common process at that time,” notes Aucoin in a 2011 interview. “We’re now talking in my own lifetime, the ’40s and ’50s and families ahead of me would have had those, so we’re going back to the early part of the 20th century, I suspect.” He goes on to say,

16 Aucoin uses the phrases “hay barrack” and “hay stack” interchangeably to refer to the same type of structure:

17 Aucoin notes the barrack preceded the hayloft in the Codroy Valley, and also served as a secondary storage facility:

The Aucoin hay stacks or barracks were 2 square metres, with hay stacked up 3 to 3.5 metres. This would give the farmer 136 cubic metres of stored hay. Such a barrack would preserve hay into the next spring, depending on hay quality and weather.

St. John’s Area Hay Barracks

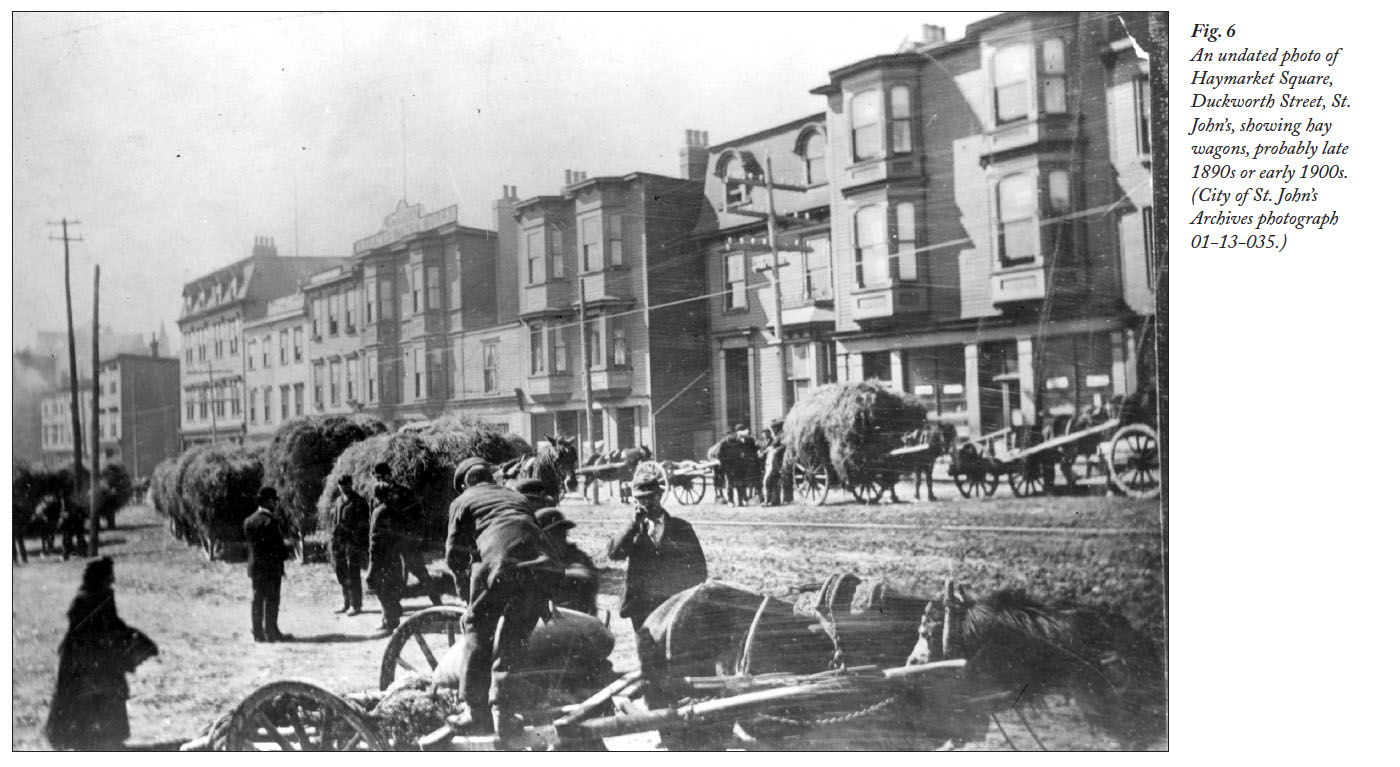

18 A number of hay barracks were on the farms around St. John’s, on the east coast of Newfoundland. “Haymaking was a ‘must’ job on all the farms in the St. John’s area, for hay was the mainstay of the cows’ and horses’ diet” writes Hilda Chaulk Murray (2002: 92). Hay was important, even in urban centres like St. John’s, where cart horses were an integral part of everyday life, well into the 20th century (Fig. 6).

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 619 On August 7, 1893, the St. John’s newspaper the Evening Telegram ran a notice for the public auction of the property of the P. Summers Estate, “beautifully situated on Topsail Road, only three miles from Cross Roads at Riverhead. The Farm contains 10 acres, 8 ½ of which are under cultivation, with a substantial Cottage, 2 Barns, and Hay Barracks thereon” (Valuable Farm 1893). Similarly, in a will dated the May 1, 1869, one William Quigley bequeathed to his son Peter Quigley and his daughters Catherine, Judy and Ann the joint use of his old farm at “Study Water,” (possibly Steady Water) on Topsail Road, and, along with bedding, furniture, utensils and horse-related gear, the “Hay Barrack” (Benson and Benoit 2013).

20 Just as in the Codroy Valley, St. John’s–area farmers used a combination of hay barracks and barns, storing hay in different locations. Ease of access was one consideration, though one St. John’s farmer, Kevin Kenny, told Murray that “[his] father never liked to have too much hay in the hayloft near the house because he was always afraid of fire” (Murray 2002: 151).

21 Murray notes that some farmers stored a great deal of hay outside of the barns in barracks (2002: 150-51); Leonard Ruby had three hay barns supplemented by six hay barracks. Murray writes,

22 In areas of greater agricultural production, this pattern of barns partnered with barracks seems to have been standard. In smaller communities, barracks were less common, or even unknown. Hay making was still important (see Pocius 1991: 118-21), but smaller-purpose hay sheds or loft spaces within stables were the norm. As an example, the small community of Tilting, Fogo Island, had at one point no fewer than five “hay houses”—one-storey buildings with an area of 11.1 or 15.6 square metres, with flat or low pitch roofs, and no windows (Mellin 2003: 190).

Decline in Use

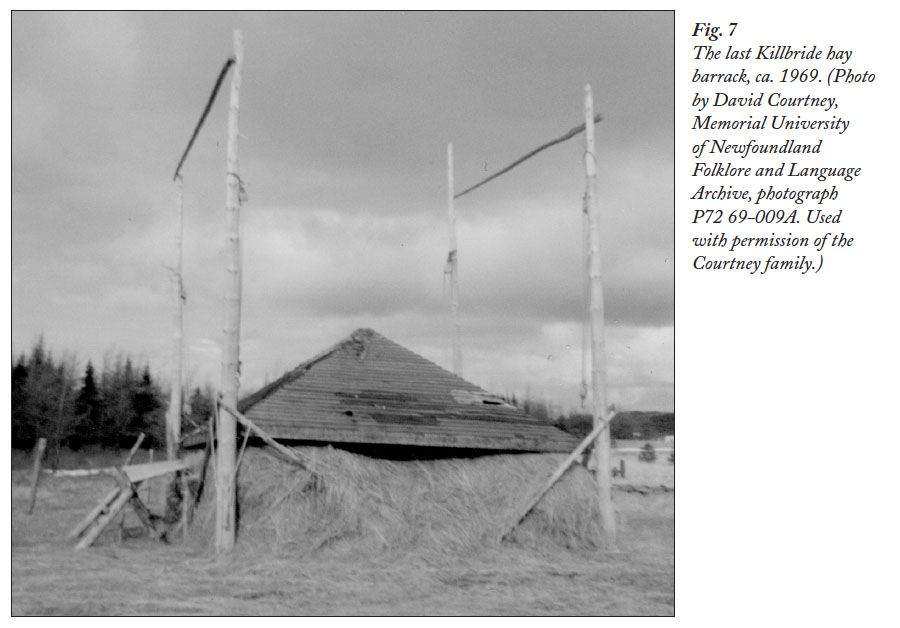

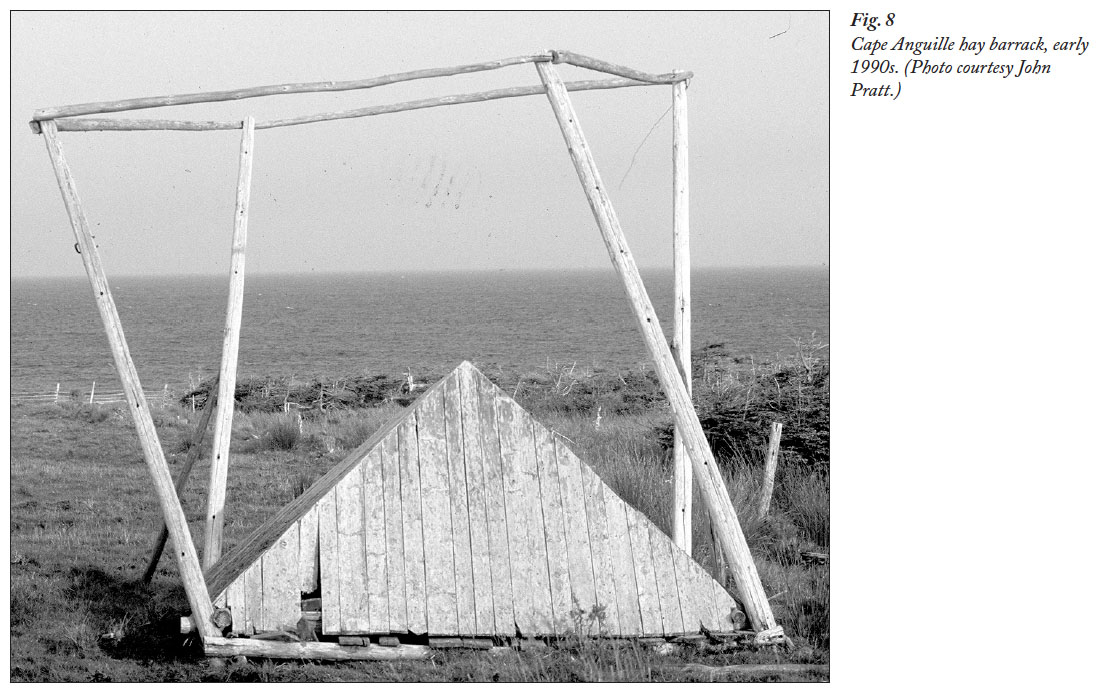

23 By the 1970s, hay barracks had started to vanish from the Newfoundland landscape. Researcher David Courtney noted ca. 1969 that as a child, the primary use of hay barracks for people of his generation was to “get in to play or shelter from the rain.” Of a hay barrack he photographed in Killbride (see Fig. 7), he stated, “this was the last of the hay barracks. As kids, we used to play cowboys, cards, and older kids used it for courting. I can remember getting put out of it many times by our grandmother” (Courtney 1969). In 1976, though most hay barracks had vanished from the St. John’s area, they were still enough in the public memory to have been included in a teacher’s guide for studying local community resources (Barry 1976: 66). One of the last documented hay barracks on the west coast of the island was that at Cape Anguille, photographed in its final days in the early 1990s (Fig. 8).

Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 7 Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 824 Today it is difficult, if not impossible, to find any hay barracks in Newfoundland, victims of changing agricultural practice and easy prey to the elements. Richard MacKinnon in 2002 described the hay barrack as “a once popular impermanent structure that is now uncommon in most North American farm districts” (2002: 27). This im- permanence of design has certainly been a factor in their gradual disappearance from the cultural landscape of Newfoundland. Like fishing stages and flakes for drying fish, barracks were never constructed to be permanent structures, and once their usefulness faded, the elements quickly took their toll. In Kansas, “wind is the major enemy of the hay roof ” wrote James Hoy in 1990 (121), echoing Newfoundland farmer Leonard Ruby’s concern about barracks and windy weather, and Peter Wacker notes that barracks “have proved to be far more transient features on the cultural landscape of New Jersey than have the Dutch barns” (1973: 38). In their 1995 field guide to North American barns, Noble and Cleek noted that hay barracks are “now very rare” (1995: 162).

25 “As farms declined, when we go through the ’60s and ’70s, many families were self-sustaining: large families, large farms, livestock and everything. As the evolution of the farm industry changed so those practices changed,” states Kevin Aucoin:

Conclusions

26 As Aucoin notes in relation to root cellars, the demise of the hay barrack tradition is a story that is repeated across Canada with vernacular buildings: corn cribs, tobacco kilns, equipment sheds, even outhouses. A study of hay barracks, as only one example, allows us to gain a better understanding of how people interact with the environment. It also gives us a starting point for oral histories, providing a point of reference for interviewer and interviewee that can lead to deeper discussions about agricultural history, subsistence, economy and change.

Special thanks to: Stephanie Courtney, daughter of the late David Courtney, for permission to use his photograph of the last of the Killbride hay barracks, and to Pauline Cox at MUNFLA for digitizing the photo; John Pratt for his photo of the Cape Anguille hay barrack; Gerard Grootveld for use of his Dutch examples; Hilde Schoefs at Domein Bokrijk for her enthusiasm, photographs and patience; Kevin Aucoin; Philip Hiscock; Helen Miller; Gail Pearcey; Nicole Penney; Christopher Pratt; and Leonard Ruby.