Articles

Living Memorials to the Civil War Dead:

Case Studies in the District of Columbia and the Commonwealth of Virginia

Abstract

As America’s Civil War laid claim to hundreds of thousands lives, it also transformed large swaths of bucolic countryside into cemeteries and memorials. This comparative study of two battlefield-located Civil War cemeteries, Battleground National Cemetery and Ball’s Bluff National Cemetery, examines the influence of natural and political forces on the aesthetics of the original sites. I argue that the land and objects on these sites function together as purveyors of specific narratives on the meaning of the war—narratives which vary dramatically based on the geographical location of the site within the Confederate–Union binary.

Résumé

La guerre de Sécession américaine, qui a coûté des centaines de milliers de vies, a également transformé de grands pans d’une campagne bucolique en cimetières et en mémoriaux. Cette étude comparative de deux cimetières de la guerre de Sécession, situés sur des champs de bataille, le Battleground National Cemetery et le Ball’s Bluff National Cemetery, examine l’influence des forces naturelles et politiques sur l’esthétique des sites originaux. J’avance que le paysage et les objets placés en ces lieux fonctionnent ensemble pour véhiculer des récits spécifiques sur le sens de la guerre—des récits qui varient spectaculairement en fonction de la localisation géographique du site au sein de la scission binaire entre Confédérés et Unionistes.

On those brave boys (Ah War! thy theft);

Some marching feet

Found pause at last by cliffs Potomac cleft;

Wakeful I mused, while in the street

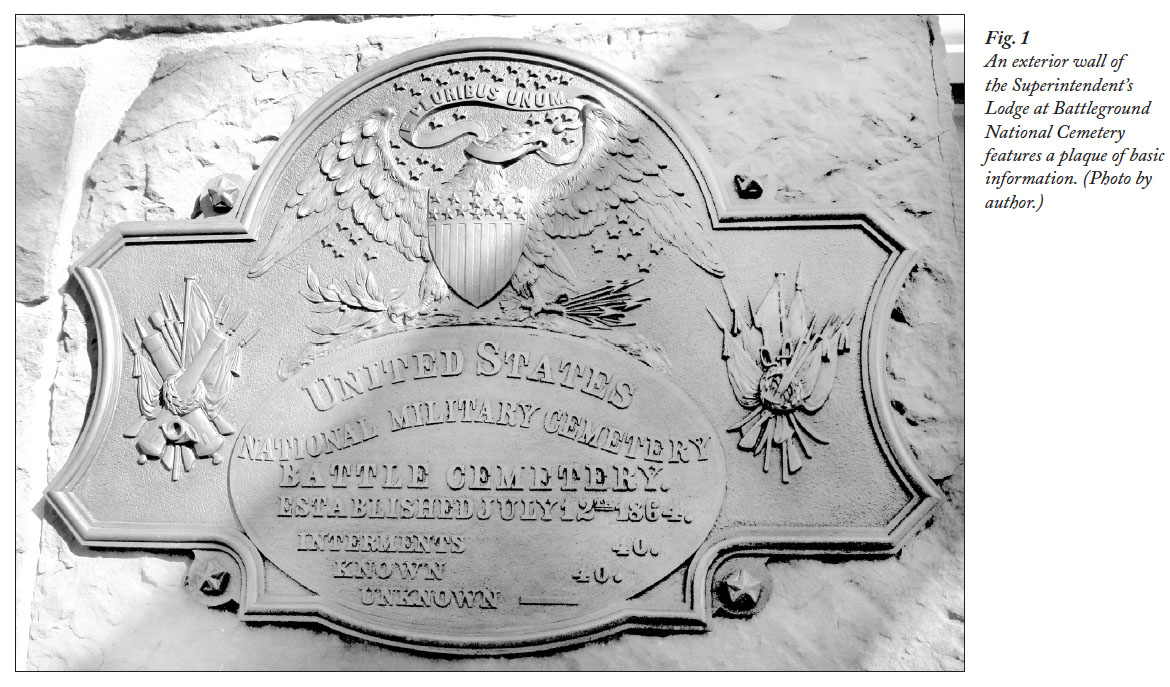

Far footfalls died away till none were left.

—Herman Melville, October 1861, “Ball’s Bluff, a Reverie”

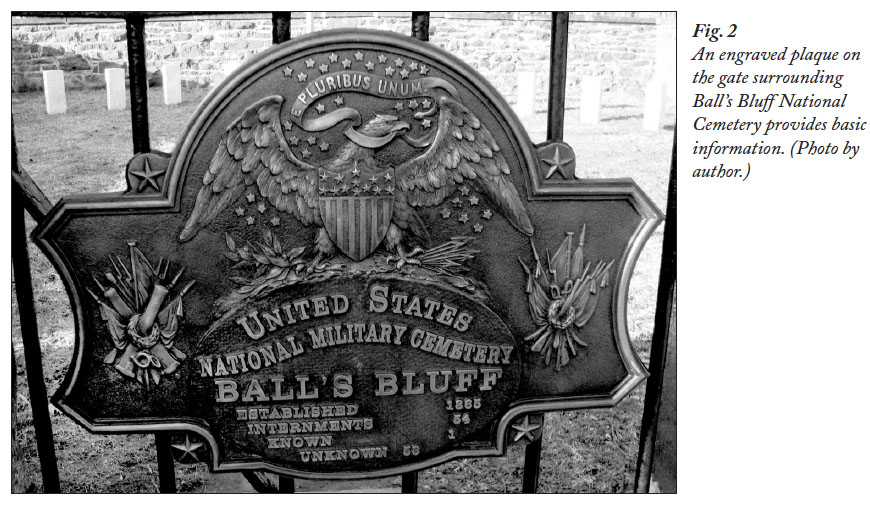

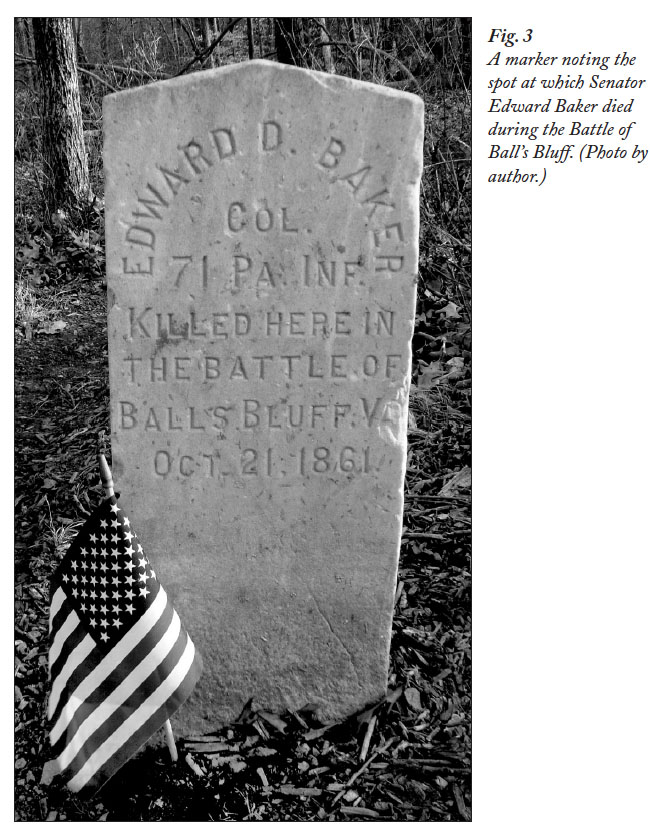

ours all, (all, all, all, finally dear to me)

—Walt Whitman, 1882, “Specimen Days: The Million Dead, Too, Summ’d Up”

1 The dust has long since settled after the last major battle of the American Civil War, yet the passage of almost 150 years has done little to reconcile the long list of unresolved “facts” that still linger. It was a war that took at least 498,332 lives, though for years estimates placed the death toll at around 620,000. More recently, improved census data raised that number to 750,000 (Department of Veterans Affairs 2011; Gilpin Faust 2008: xi; Gugliotta 2012). Moreover, the identities of many who perished remain unresolved: over 40 per cent of Civil War casualties were never identified, and around 66 per cent of Black soldiers are still unidentified (Public Broadcasting Service 2013). Today, 115 designated national cemeteries across the country house the remains of Civil War veterans, all of which are funded and maintained by federal tax dollars. Some are situated in regions far removed from combat zones—there are two in California—yet far more are located atop the very battlefields upon which thousands perished.

2 What we do know about the Civil War is that it echoes loudly through contemporary literature and academia. Author Drew Gilpin Faust’s examination of death in the Civil War, This Republic of Suffering, landed on national popular bestseller lists in 2008, as did Tony Horowitz’s Confederates in the Attic in 1999 and Bill O’Reilly’s Killing Lincoln in 2011. Yale University Civil War scholar David Blight posits that since the surrender at Appomattox, more than 65,000 books have been written on the topic (2008). A 1990 New York Times headline read, “Remarkably, Din of Civil War is Growing Louder” (Hall 1994: 7), and, indeed, approximately 30,000 people regularly participate in Civil War re-enactments across America. In February of 2013, a consortium of universities and performing arts centres launched the National Civil War Project, which aims to create theatrical interpretations about the war in commemoration of its 150th anniversary (Lee 2013). In 2012, two Civil War movies—Django Unchained and Lincoln—earned several Academy Awards and great critical acclaim. David Blight offers explanations for the War’s “hold on the American historical imagination,” such as our fondness for redemption narratives and lost cause stories, the search for national origins and the perception of the Civil War as a point of “racial reckoning” (2008).

3 The Civil War retains the power to move people, both emotionally and literally, to the physical spaces of its battlefields. Its cemeteries draw millions of visitors every year. For a topic about which so much remains unknown, our collective fascination is nonetheless tangibly present. In 2012, at a few notable mid-Atlantic area sites alone, the visitation statistics are staggering: 510,921 at Antietam; 320,668 at Appomattox Court House; 982,324 at Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania; 1,126,577 at Gettysburg. Locations in the south, north and west also see impressive numbers each year (Visitors Use Statistics 2012), and the public interest in Civil War sites dwarfs that in many other contemporary national historic landmarks. The math is even more compelling given that there are no comprehensive statistics on the numerous privately owned and maintained sites. Together, these places occupy a substantial place in the physical, fiscal and cultural landscapes of America, and the issues they represent are still debated today.

4 Wars generate a plethora of written records from which we can piece together a relatively accurate picture of how people lived by reading their dairies, court records, land deeds, enlistment data, wills, tax documents, birth/baptismal certificates, building contracts and financial ledgers—seemingly complete records of a human life. Yet the public does not routinely review these documents, which serve as relics from and evidence of a bygone time. In contrast, Americans flock to Civil War cemeteries in impressive numbers, constantly engaging with those hallowed burial grounds. In his seminal work on material culture, In Small Things Forgotten, James Deetz writes that archaeology is “the study of past peoples based on the things they left behind and the ways they left their imprint on the world” (1977: 4). In a cemetery, the “past peoples” who left their imprints are not actually those buried within, but rather the messy alliance of governments, bereaved loved ones and landowners who carved out and preserved those spaces. What differentiates the objects “left behind” in cemeteries—tombstones, placards, fences—from those things in the written record is the way in which they physically take up space, demanding to be acknowledged and interpreted in the 21st century.

5 Examining this particular type of built environment is illuminating because it speaks to the ways in which Civil War military deaths were understood at the time of each cemetery’s creation, as well as the ongoing interpretation of those deaths today. Unlike a museum artifact, cemeteries located at their corresponding battlefields cannot be taken outside of their original context; the historical accuracy of any such study depends upon factors of geography, a key player in determining the winners and losers of large ground wars. The fact that such sites have been largely preserved in concert with their original design offers a strong statement on the place of the Civil War in the American mind and our retrospective understanding of it: Civil War soldiers died on American soil while fighting in a war that has since been used as an origin story for innumerable aspects of modern American culture. Civil War cemeteries are both frozen in time and singularly current.

6 Death, place and memory come to an important intersection in Civil War cemeteries. Integral in all three are ideas of ephemerality and permanence—the brevity of a human life or a battle is undeniable, and, accordingly, we attempt to make these things last, literally carving them in stone. The violence of the war and the meaning of any given soldier’s life are well beyond living memory. At one time, though, almost every American directly experienced those things: a mourned son, a lifetime of hardship following the death of a breadwinner, the end of a family name, and all of the other anxieties of a nation on the brink of implosion. Once buried, the Civil War dead came to belong to a collective memory. When all actual memories have faded, their collective presence continues to give voice to the tragic fact of their untimely deaths. Where the written record proves insufficient, we can examine the ways in which we have collectively chosen to make cemeteries—the physical embodiment of Civil War loss—into the quintessence of a specific moment in time and our amalgamated understandings of it.

7 I will explore the modern memorialization of the Civil War by examining two military battlefield cemeteries in the Washington, DC, area, the geographical focal point of the war: Battleground National Cemetery in the District of Columbia and Ball’s Bluff National Cemetery in Leesburg, Virginia. Both are federally designated national cemeteries and neither accepts new burials. Due to this inactivity, the Civil War becomes the sole moment in history that shapes their relevance and draws visitors. Methodologically speaking, it is important to isolate this aspect since other Civil War–era locations also bury modern war casualties and veterans. Comparable in size and historical significance, each is a crucible for Civil War memory where the very historical facts of secession, rebellion, slavery and mass death are made physical by virtue of their ongoing existence in the American landscape.

Influential Scholars

8 While numerous scholars study the Civil War as a whole, the macabre facts of death in that time are far less popular subject matter. In This Republic of Suffering, Drew Gilpin Faust articulates the ways in which the Civil War impacted the popular understanding of death as a concept and resulted in far-reaching commodification of the products and processes associated with death. As she shrewdly puts it, “Making a killing seemed to be in every sense the work at hand” (2008: 96), as everyone stood to profit—including the occasional predatory embalmers who extorted mourning families. Innumerable military casualties necessitated the institution of everything from dog tags to appropriate documentation of casualties to proper notification of the bereaved. Generally, all deaths came to include metal caskets, embalming and standardized procedures as a result of the war’s massive scale (see Gilpin Faust 2008: xi). Since that time, death has had an economy all its own. Faust’s approach to the war’s influence is rooted in numbers: hundreds of thousands killed and millions more affected deeply. The Civil War, she writes, violated the dominant conventions about who should die and how and where that should happen (the “Good Death”). She goes so far as to say that “at war’s end this shared suffering would override persisting differences about the meanings of race, citizenship, and nationhood to establish sacrifice and its memorialization as the ground on which North and South would ultimately reunite” (xiii).

9 While there is compelling physical evidence in military cemeteries that sacrifice for one’s country is indeed a definitive American value, other scholars emphasize the lopsided nature of the memorialization itself. John Neff is one such example. In his 2005 book, Honoring the Civil War Dead, he describes the ways in which the North “dominated” war commemoration. According to Neff, one side had to preside over this task due to the nature of a civil war. The financial disparities are obvious; the South was destitute and unable to engage in large-scale commemoration. Neff writes, “Southern states could not hope to match the funds or manpower poured into the effort of remembering and honoring a national interpretation of the war, even if they had been allowed to do so” (2005: 141). Yet the moral imperatives, Neff argues, were also oriented toward the North, whose “memories had been legitimated by victory, not called into question by defeat” (107). He posits that Abraham Lincoln himself took ownership of this ideal in the Gettysburg Address when he asserted that “these dead shall not have died in vain.” To Neff, “these dead” clearly refers to Union dead alone (107). Indeed, he has good reason to argue as much: when a massive post-war federal reburial effort took place, the decision of whether or not to include Confederate dead resulted in months of impassioned public legal sparring, which Neff characterizes as “tortured” (124). The overall result was the product of both civilian and military authorities, and, eventually, years later, Confederate soldiers were indeed included. As the government took new ownership of its logistical responsibilities amid a new death culture, the material aspects of war memorialization were very much consciously decided, if hotly debated. The Civil War became a momentous period in American history as soon as it began. The sheer volume of the dead brought about a serious, national reflection on death, a self-examination that continues today.

Battleground National Cemetery, Created July 1864

10 Confederate (South) and Union (North) forces clashed in the Battle of Fort Stevens on July 11 and 12, 1864. Confederate Major General Jubal Early led an attack on the Fort Stevens fortifications in a bid to take the capital in what was to be the last of the great Confederate incursions into Union territory. Although Union leaders were disturbed by the intrusion into Washington, DC, and President Lincoln himself came under fire by Confederate sharpshooters,1 Union Major Generals Alexander McDowell McCook and Horatio Gouverneur Wright repelled the effort with relatively little effort and minimal bloodshed. Once the skirmishing ended, the living had to attend to the dead. In wartime, initial burials were rushed acts of necessity, dictated by the urgency of burying the corpses that would soon create deadly vectors for disease. Frequently, captured prisoners of war and regiments from the Colored Troops were placed on burial detail, tasked with interring sometimes innumerable corpses of fallen soldiers, most of whom had died far from home.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 111 In this case, burials began right away. National Park Service records of casualty numbers (which include both dead and wounded) are inconsistent: one source places the number at 874 for both armies, and another lists the total as “over 900” (National Park Service 2013a). The discrepancy is reflective of the systemic failure in Civil War record keeping. Regardless of precise totals, the Union interred 40 of its own, all white. Had there been Black soldiers among the deceased, they would have been buried separately, segregated in death as in life—a notable fact given that the cemetery today lies largely ignored in an historically Black neighbourhood in an historically Black city. Within days of the battle, Montgomery Miegs, Quartermaster General of the Army, seized a single acre of battlefield land and ordered the Union dead buried there. Lincoln later dedicated the site in person. The land, at that time used as an orchard, belonged to a farmer named James Malloy, who viewed the seizure as inappropriate, and likely costly, given that it was functioning farmland. Malloy filed suit, and on February 22, 1867, Congress voted to render payment to Malloy to compensate him for the seizure and legally transfer the land into government ownership. Payment was made on July 23, 1868 (United States Congress 1921). Seventy-two years later in 1936, a final burial occurred with the interment of battle veteran Edward R. Campbell, bringing the total to 41 graves.

12 With those near-immediate burials, the Union Army reshaped James Malloy’s orchard into another thing altogether—a national memorial. As Northern troops buried Northern dead, they froze that plot of land in a moment of Civil War time. The final burial of Campbell only strengthened that memory, though today the sprawl of development has changed its physical context dramatically and morphed the rural location into an urban one. The land today has been so wholly subdivided that the battlefield mostly lies beneath city streets and apartments buildings and is not visible from the cemetery. The physical relationship between the two has been forever lost, as has their geographical position atop Washington, DC, from which the White House was once easily visible. Though the government initially protected the land and designated the cemetery, it shrank beyond recognition over the years. In comparable examples, such as the following case study on Ball’s Bluff, the Civil War is similarly viewed as the defining moment for a space, yet its broader environment is handled very differently.

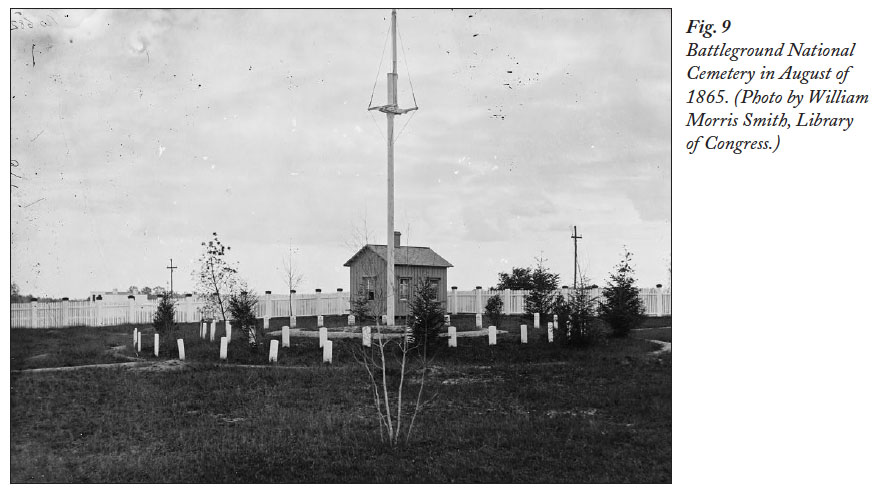

Ball’s Bluff National Cemetery, Created December 1865

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 213 The Battle of Ball’s Bluff on October 21, 1861, was a fight that never should have happened. The day before it occurred, a Union reconnaissance party in modern-day Loudon Country, Virginia, crossed the Potomac River to take stock of Confederate encampments. Inexperience and poor visibility led to an inaccurate report: Union soldiers reported an enemy camp where there was in fact only a hedge of trees. The following morning, Colonel Edward Dickson Baker, also a U.S. Senator, ordered a small number of soldiers to cross the river, despite the grossly inadequate number of boats. When they unexpectedly encountered the enemy on the other side, they were scattered and unorganized, while the Confederates mustered standby forces quickly. In the end, Confederate soldiers chased Union soldiers off of the bluff and onto the rocky waters below. Baker was mortally wounded. Many drowned, and for weeks their bodies washed downstream into Washington (United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service 1984). As one Union captain wrote, “The cause of this sad havoc was that we had no proper means of transit and retreat” (Stone 1861). The obvious horror of this image is one reason the battle fomented considerable political rage. The other reason, however, was more personal for many politicians: botched reconnaissance resulted in the death of a sitting Senator who also happened to be a close personal friend of Lincoln (Fig. 3).

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 314 Unlike Battleground National Cemetery, which became an official cemetery within days of the skirmish, Ball’s Bluff National Cemetery formally came into being four years after the Battle of Ball’s Bluff—this both despite and in part because of the political sensitivities surrounding the battle. Still, of course, the burying of the dead was a task that could not wait. A day after the battle, a Union officer led ten men back across the river “under a flag of truce ... to bury our dead upon the field” (Baltz 1888). The soldiers buried forty-seven dead and left approximately twenty-five others unburied, due to the darkness of nightfall. It should be noted that this information refers only to the dead who fell on the field; certainly more bodies lay hidden in the underbrush of the forest. In the end, the burial crew interred fifty-four dead in twenty-five graves, all but one of whom were never identified. Casualty reports from this battle are extremely inconsistent due to the chaos and probable drowning of many missing soldiers.2 Above all, these circumstances reflect the tension between a sense of propriety, the pressing needs of hygiene and the difficulty of record-keeping in the field.

15 The land for the cemetery and park was donated in 1865, although its ownership status was disputed at the time. In 1870, Margaret Jackson received clear title to the land. One year later, she sold 16.5 hectares of it to Thomas Swann.3 In 1870, Swann sold enough land for a cemetery and access road to the federal government (Gressitt 2006). In 1876, the Quartermaster General’s Department produced a map and detailed description of the land’s layout, specifying that the cemetery consisted of “eight perches of land” (approximately 200 square metres; United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service 1984). Thirty years later, in 1906, President Roosevelt approved an act of Congress to acquire by donation an additional tract of land to create a right-of-way for a new road. The following year, the federal government constructed a fenced approach road 2.1 kilometres in length to connect the cemetery to a road, now U.S. 15. The 1980 National Register of Historic Places Nomination form specifically states that “Except for the tree-lined gravel approach road, the appearance of the Ball’s Bluff National Cemetery has not changed in more than 100 years” (1984). The land itself serves as a useful illustration of the consistency with which the whole site, natural and man-made aspects together, has been regarded as a rural memorial to the Civil War. Unlike Battleground National Cemetery, much of the land here was acquired by donation rather than seizure, and additional land was actively pursued and attained within the lifetime of battle veterans. The park has continued to expand over time through both private donations and land purchases by the Northern Virginia Regional Park Authority. The original purchase and subsequent expansions further cemented the spatial separation of the battlefield and cemetery from the rest of Leesburg and any new housing developments. Its size and use today have been fastidiously curated by Virginia state and local entities—a surprising reversal of power for a state whose Civil War legacy is largely one of loss. This preservation is an ode to the land’s representative position in the heart of the Confederate wilderness.

Civil War Memory

16 In 1867, Congress passed “a bill to establish and protect national cemeteries” (Gilpin Faust 2008: 243), and it was not until decades later that Confederate sections were added to select cemeteries. Prior to that, Confederate dead were buried by private citizens or merely left in repose where they died. As John Neff puts it, “national cemetery is best thought of as a synonym for Union cemetery” (Neff 2005: 132; emphasis in original). Where they existed, though, these privately owned Confederate cemeteries served as emotional rallying points for Southerners reluctant to accept their return to Union citizenship. It was no less than a threat to federal ideology. Eventually President McKinley championed the effort to fold Confederate graves into national cemeteries and ordered the reinterment of Southern dead at Arlington. It was a genius stroke by which to subvert lingering Confederate ideology—removing hallowed Southern cemeteries took away secessionist holy ground. Carried out mostly by U.S. Colored Troop units, the process took years. Today, the federal government cares for more than 30,000 Confederate graves in the North (Poole 2009), though private cemeteries persist in many Southern and Mid-Atlantic areas.

17 Even today, inherent in any comparison of Ball’s Bluff and Battleground National Cemeteries is the tension between representations of two different governmental ideologies of North/South and Union/Confederate. Key historical figures serve as counterparts to one another on this binary—Union General Ulysses S. Grant and Confederate General Robert. E. Lee, or President Abraham Lincoln and Confederate President Jefferson Davis. These comparisons only contribute to a perspective that equates the South with the North, a narrative that any chartered federal government would resist. The establishment of Union cemeteries across the South was the physical embodiment of a victor’s retribution over its conquered territories—a way for the North to appropriate actual land even in the heart of the South (Gilpin Faust 2008: 243).

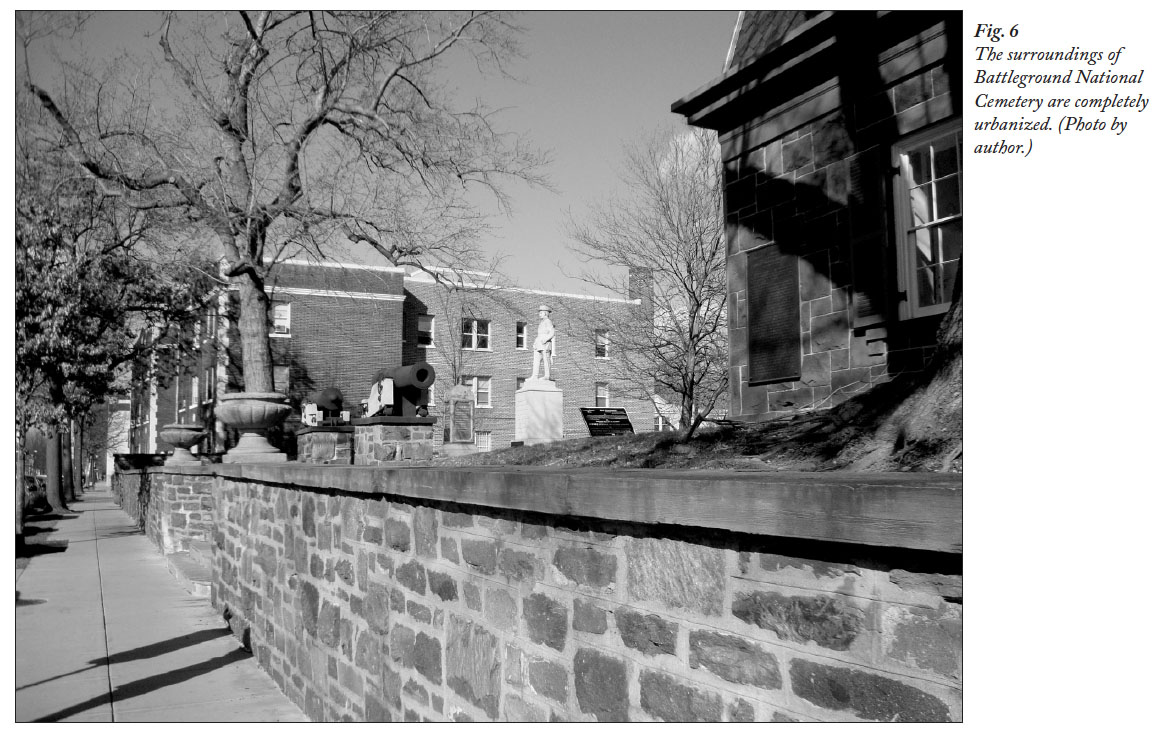

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4 Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 518 Today, the geography of Fort Stevens and Battleground National Cemetery illustrates the intensity of urban development in this section of DC. Though at the time of battle the burials were “on site,” today there are two definitively separate locations; the cemetery is located 4.5 blocks north of the fort (Fig. 6). Visitors access the cemetery site via its entrance on Georgia Avenue in the present-day neighbourhood of Brightwood. Prior to the Civil War, the land immediately surrounding Fort Stevens was owned by the Emory Methodist Church and a number of free Black landowners living in the neighbourhood they knew as Vinegar Hill (National Park Service 2004). Today, Brightwood is located in Ward 4 in the upper northwestern quadrant of Washington. It rests near the top of the city’s elevation rise, and its impressive height harkens back to a oncestrategic location. Georgia Avenue itself contains most of the retail in the area, to which there is no easy access by metro; the Takoma Park and Fort Totten metro stations are walkable from the periphery of the neighbourhood’s northern portion. The opening of condominium units at the intersection of Georgia and Missouri Avenues in 2006 and a Walmart nearby in 2013 have brought about intense debate over issues of gentrification, preservation, racial polarization and affordability.

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 619 As such, a national military cemetery—albeit a small one—is an unexpected feature on Georgia Avenue. What was once a relatively flat orchard is now demarcated by a stone retaining wall that abuts the sidewalk and encircles the small rectangular plot of land. 4 It appears to receive few visitors. Aspects of Battleground National Cemetery are nearly identical to those of Ball’s Bluff. Grave markers of a standard design, identical in all military cemeteries, surround a central flagpole, a layout common among Civil War cemeteries.5 In both cemeteries in this case study, an excerpt from Theodore O’Hara’s “The Bivouac of the Dead” features prominently on bronze placards near the tombstones:

Dear as the blood ye gave.

No impious here shall tread

The herbage of your grave.

Although the poem takes the form of a message to the deceased themselves, it highlights the aspirational ideals of an eternally respectful mourning people. Originally written in homage to the Mexican War dead, O’Hara’s words are a mainstay in Civil War memorialization. The poem itself is epic in length, glorifies battle and, perhaps most importantly, carries a message of peaceful rest for the fallen that does not differentiate between Union and Confederate.

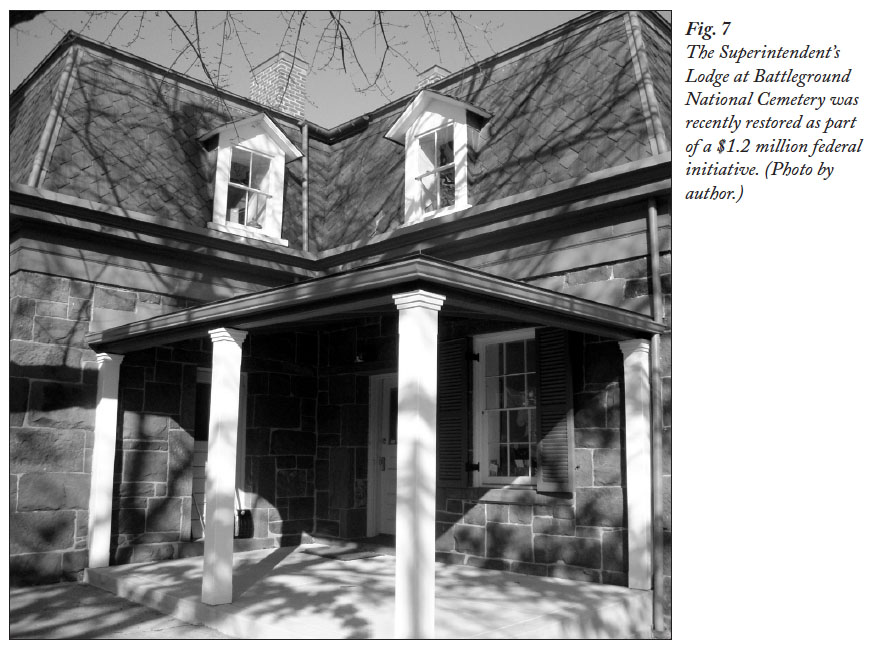

20 There are also characteristics of the site that mark it as distinctly federal. The red sandstone superintendent’s lodge at Battleground National Cemetery (Fig. 7) utilizes a standardized design, a reflection of the Civil War’s organizational legacy, a result of the need to move huge quantities of people and supplies across the country (Architrave 2004). Workers completed construction of the lodge seven years after the first burials took place. Design features include four obelisk-shaped monuments,6 Grecian-style urns, informational plaques, two Civil War–era 2.7 kg smoothbore cannons and a transcript of the Gettysburg Address inscribed on a bronze placard—another common feature in Civil War cemeteries. The urns function as memorials unto themselves, utilized “when the body of the deceased is not present in the burying ground” (Deetz 1977: 123), a pervasive problem in the Civil War especially. The guns are equally visible from the street, and serve two fundamental aesthetic purposes. First, displaying the implements of war foregrounds its violence but allows for a level of detachment from gore or brutality. Second, they orient the viewer to a very specific historical period in which such weapons were the height of fighting technology—they represent a merger of industrialization and warfare.

Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 721 Together, these design elements indicate the ways in which their creators wanted the war to be remembered. They fall short, however, of specifying the ways in which the war is remembered today, particularly by certain groups of people like Black Americans. Battleground National Cemetery is an excellent illustration of “why civil wars are such vexing, difficult problems in nations’ memories once they’ve had them” (Blight 2008). Everyone suffered tragic loss. Northerners and Rebel forces alike also died by the thousands, the latter sent home to grapple with the consequences of defeat. Black Americans, in particular, endured extreme hardship, and thus experienced the end of slavery as a critical turning point. David Blight calls Emancipation “the single most revolutionary result of the Civil War and arguably the single most revolutionary historical moment in American history ... the liberation of 4.2 million slaves to some kind of freedom and some kind of citizenship” (2008). His qualifiers—some kind of freedom and some kind of citizenship—are very much intentional. Liberation from slavery was not, he opines, a “jubilee.”

22 The Civil War makes screaming comments on race and the necessity of radical action, pivotal on the road to today. Yet there is room for another interpretation. The massive uphill struggle of Black Americans for equal treatment under the law as full-fledged citizens was just beginning when the war officially came to a close. A designated national cemetery exalts that time, the very beginning of the journey, in an arguably inappropriate way. As Kirk Savage writes in Monument Wars, “national monuments acquire authority by affixing certain words and images to particular places meant to be distinctive and permanent. Thus, monuments stand apart from everyday experience and seem to promise something eternal, akin to the sacred” (Savage 2009: 6). To so glorify a time period of pervasive abject injustice in an historically Black neighbourhood can erode and discredit the historical legacy of slavery as an ongoing disadvantage to its descendants today.

23 Battleground National Cemetery cannot be called a genuine DC tourist destination by any stretch of the imagination. Of equal relevance, however, is the lack of effort on anyone’s part to market it as such. It appears as one stop on the Brightwood African American Heritage Trail of Cultural Tourism DC, a nonprofit organization. The city’s Chamber of Commerce and official tourism websites do not include entries on it, seemingly dwarfed as it is by the looming presence of Arlington National Cemetery just across the river. It is important to note that just as our collective view of the Civil War is not static, the cemetery itself has undergone changes over time as well, including the addition of a pillared rostrum, the burial of one superintendent’s family in a separate section of the site and the development of the immediate surroundings from open land into a densely populated residential area. The latter, this fragmentation of the cemetery from the battlefield, is a seminal change. That separation destroyed the cohesive landscape that gave the site its original historical context; with it went the raw size and scale that would have provided a powerful physical memory. We have only black and white pictures by which to know of the haunting serenity of its gentle slopes once dotted with trees.

24 The War Department maintained the cemetery until 1933, at which point it was transferred to the care of the National Park Service along with all other national cemeteries. The National Register of Historic Places added the site to its listing on April 4, 1980. It appears that shortly thereafter the cemetery fell into a state of disrepair, and by 2005 the DC Preservation League listed it as one of the most endangered sites in the city. Four years later, in 2009, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act funded a $1.2 million refurbishment of the superintendent’s lodge and adjacent rostrum, completed in March of 2010. Though it may sound like an enormous sum, historic structures are extremely costly to preserve, and the Department of the Interior categorized the work as “deferred maintenance” (Department of the Interior Recovery Investments 2013). In other words, the only recent expenditures on this site financed profoundly necessary and overdue restoration work; there is no indication that the expense resulted in greater exposure or interest to tourists and the local community.

25 Leesburg, Virginia, sits 53.1 kilometres northwest along the paths of several Union and Confederate battle campaigns. The 1860 census listed the town’s population as 1,130. Today, Leesburg claims 42,616 residents, 71 per cent of whom identify as white (the Black population is 9.5 per cent; United States Census Bureau 2010). Although it boasts an impressive downtown historic district that is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, the bulk of Leesburg is consumed by subdivisions and relatively new middle- and upper-middle-class housing developments. Its retail economy is strong, and there are large outlet malls in addition to smaller shops, yet the real commerce in Leesburg caters to mega-sized government units, contractors and private companies. A massive conference centre and underground maze of connected buildings offer square footage at a price that would be unfeasible in Washington.

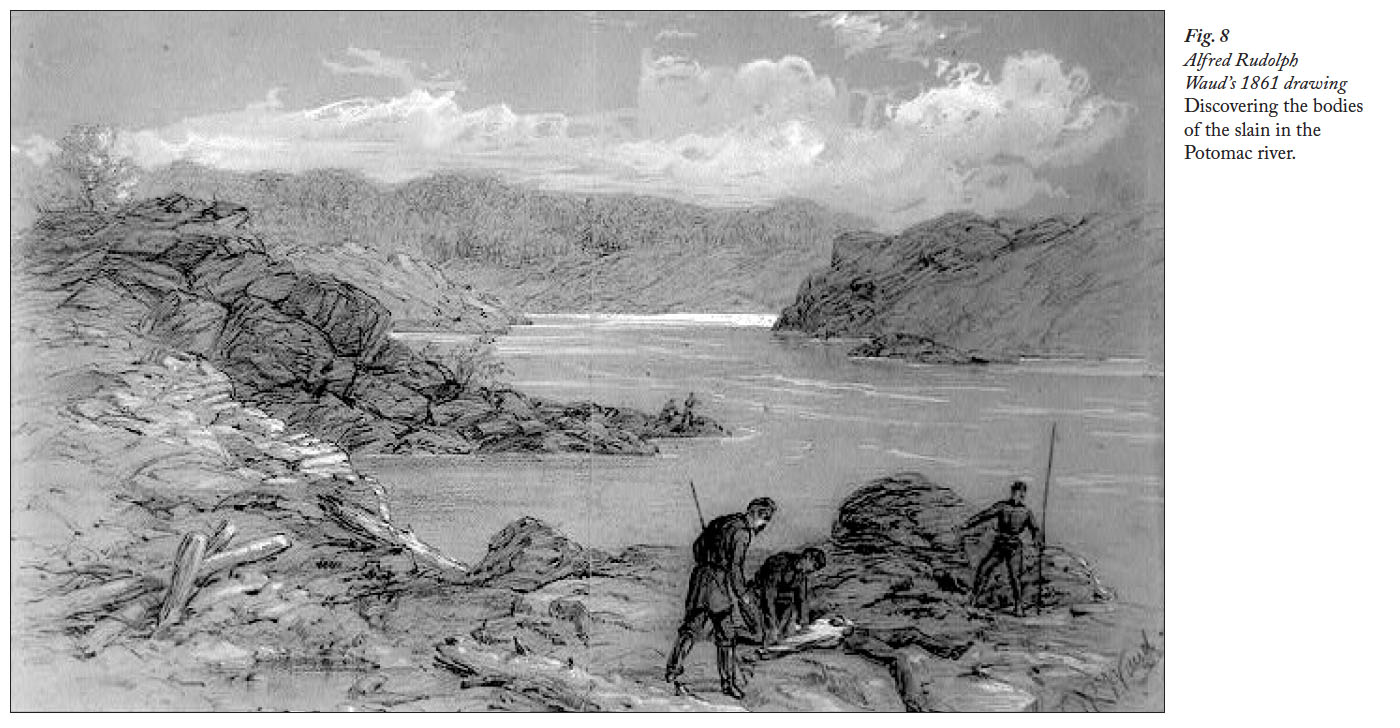

26 The approach to Ball’s Bluff is a surprising one. A multitude of red, white and blue Virginia Civil War Trails signs with their distinctive bugle emblem direct visitors from the main road into an affluent subdivision. At the paved road’s dead end, cars proceed up a dirt road to the parking lot. Designated a National Historic Landmark in 1984, the park’s 90.25 hectares contain more than 11.25 kilometres of marked trails on which couples and families hike, often with dogs. A short brick fence and wrought iron gate enclose the cemetery, 25 graves surrounding a flagpole. The federal government maintains only this very small section of the park; the Northern Virginia Regional Park Authority (NVRPA) cares for the vast remainder. NVRPA has steadily acquired additional tracts of adjacent land since the 1980s to augment the park, adding 68 hectares by private donation in 1986, then purchasing 22.25 hectares additional in 2000. Strategic manipulation of the hilly terrain by Confederate forces made for a dramatic battle scene in the fields and forests. Modern NVPRA efforts have maintained the curvature and growth of the land in such a way that matches descriptions and photographs from the Civil War (Fig. 8). NVPRA described its 2004 decision to cut back tree and underbrush growth as an effort “to make battlefield interpretation efforts more effective” (Northern Virginia Regional Park Authority 2014), indicating that the park’s overall usage involves large-scale Civil War events and spectators, a luxury very much foreign to Battleground National Cemetery on the other side of the Potomac. Carefully applied funding, in other words, effectively preserves the spaces that shape public consciousness.

Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 827 Although the cemetery’s design bears a strong resemblance to its Washington, DC, counterpart, the subtle differences are telling. The iron gates are nearly identical, yet in Leesburg, a placard states that its most recent restoration was courtesy of the local Sons of Confederate Veterans “with the cooperation” of the NVRPA and the Department of Veterans Affairs—a direct indication of the private interests and funds participating in the space. Both cemeteries display placards of O’Hara’s “The Bivouac of the Dead” with slightly different display formats, yet in Leesburg the poem is located outside of the fenced cemetery, rather than within it. There is no evidence signifying whether it was placed there by the NVRPA or the federal government, an ambiguity that does not exist at Battleground National Cemetery, which is entirely federally operated by nearby Culpeper National Cemetery. Outside the cemetery fence are two monuments, one relatively close by dedicated to fallen Senator Edward Dickinson Baker and another at least 90 metres away, to fallen Confederate soldier Clinton Hatcher, who “Fell Bravely Defending his Native State.” The National Park Service explicitly states that “there is no available information as to when or by whom this marker was erected” (United States Department of the Interior 1984). Yet the laudatory tone praising the courage of a dead Confederate soldier seems to indicate the power of private dollars at work. The most substantive difference between the two cemeteries relates to identity: at Ball’s Bluff, 53 of 54 soldiers remain unknown. Battleground National Cemetery, in contrast, cares in perpetuity for the remains of 40 soldiers, all of whom have been identified. At Ball’s Bluff, every marker reads either UNKNOWN or UNKNOWN SOLDIER with the exception of a solitary marked grave for James Allen of the 15th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry. The innumerable unknown dead were always a poignant topic. As Whitman wrote,

28 Much of the Civil War, in fact, retains a poignant presence in Virginia. Its sites are aggressively and successfully marketed as cultural assets and tourist destinations. The NVRPA maintains a strong online presence for Ball’s Bluff (Northern Virginia Regional Park Authority 2014) and produced a 23-page Management Plan detailing goals and resource management strategies for the park (Northern Virginia Regional Park Authority 2004). Loudon County features Ball’s Bluff in its own sleek tourism campaign, “Take It In,” which includes videos of on-site re-enactors in full uniform (Visit Loudon 2013). The park is also included in Journey Through Hallowed Ground advertisements ( Journey Through Hallowed Ground 2013), a multistate partnership intended to capitalize upon cultural history in the Mid-Atlantic region. Journey Through Hallowed Ground works with the local public school system to incorporate Ball’s Bluff battlefield and cemetery histories into its curricula, posting students’ completed projects online ( Journey Through Hallowed Ground 2012). In short, not only is Ball’s Bluff energetically presented to the community, it is genuinely active in Leesburg’s cultural landscape.

29 To the residents of Leesburg, the Civil War continues to articulate itself in a way that is understandable and meaningful in the new millennium. More accurately, Virginians choose to maintain its importance. The same is not true of Battleground National Cemetery in Washington, DC, whose neighbours are unlikely to drop by and whose merits are not effectively extolled by any government or tourist agencies. These small cemeteries represent small battles, yet there is a massive difference in the size of the parks themselves. Washington has reduced its site to the graves themselves and a tiny plot of land around them; Leesburg has made Ball’s Bluff into a massive outdoor recreation destination. Where ambient noise and passing ambulances are pervasive in the former, tranquil silence and wildlife are the only audible sounds in the latter.

30 In 1990, Congress appointed a 15-member Civil War Sites Advisory Commission to identify, assess and rate Civil War sites according to their importance and integrity, then recommend appropriate courses of action for each. The results of their assessment are radically different in the course of actions, despite striking similarities in the results of the assessment. The Commission placed both sites in the Class B category of military importance—“having a direct and decisive influence on their campaign” (National Park Service 2013c)—yet only pressed for “additional protection” for Ball’s Bluff, which it classified as having “Good Integrity/Low Threats.” By contrast, Fort Stevens and the Battleground National Cemetery several blocks away are in an unranked category for “fragmented” battlefields: “Lost integrity” (National Park Service 2013b). Very little of the original core area of the battlefield remains, most of which is now overcome by urbanization. A 1993 report identified it as “a site that could offer little more than opportunity for commemoration” (National Park Service 2009). This loss of integrity is also a loss of voice. The battlefields of rural Virginia remain audible in part because they do not compete with the innumerable stimulations of urban living. In contrast, Battleground National Cemetery (Fig. 9), devoid of geographic context and integrity in the eyes of the Park Service, has fallen silent in its failure to articulate relevancy in an active and ever-changing urban landscape.

Display large image of Figure 9

Display large image of Figure 931 The old adage that victors write the history books is only true if those victors commit to doing the writing. The 1980 National Register of Historic Places nomination form for Battleground National Cemetery testifies to its slow degradation in quality: “The cemetery once contained some 40 trees and a boxwood hedge flanking the entrance walkway, creating a richly vegetated appearance. The boxwood is gone and only about a dozen trees remain. Large stumps testify to the tree loss” (United States Department of the Interior 1980). The nomination itself is very different from that of its rural counterpart at only six pages in length with hand-drawn sketches; the Ball’s Bluff nomination is an intricately and professionally researched behemoth of a document, thirty-three pages in length. To say that all persons have truly forsaken Battleground cemetery is an exaggeration, and indeed the National Park Service hosted a 2011 rededication ceremony after the completion of restoration work funded by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. Nonetheless, the very seat of the federal government is not the place you might expect to find a near-total failure of Civil War preservation.

The Dead and the Living

32 If winners write the history books, everything indicates that Fort Stevens would lay claim to an active winner’s narrative: the federal government won the battle, and indeed the whole war; the identity of every soldier interred therein is known and Lincoln himself dedicated the site, ordaining it as a permanent holy site for the Union. By every measure, Ball’s Bluff should be a show of federal force, standing in perpetual homage to those slain in defense of the Union; though Northerners may have lost this specific battle, in winning the war they achieved the power to dictate the narrative of war memory. Instead, the federal government’s aforementioned appropriation of Southern land for Northern cemeteries has actually come to serve the story of the South in the American psyche. Rather than a focus on the outcome of the Battle of Ball’s Bluff, the state and regional authorities in Virginia promote its memory as part of a war that still shapes its self-image today. Despite its status under Union control since 1865, Virginia has managed to reclaim and re-write the Civil War narrative. The national cemetery at Ball’s Bluff (Fig. 10), a humble and unimpressive sight, is dwarfed by the surrounding Northern Virginia Regional Park. Here, the state’s efforts have managed to quietly usurp those of the federal government.

Display large image of Figure 10

Display large image of Figure 1033 It is perhaps the anonymity of Ball’s Bluff that lends itself so well to a new Southern control; unknown soldiers can serve as placeholders for all Civil War dead. They can be, as Drew Gilpin Faust puts it, an “imagined community for the Confederacy.... These men were now part of the Confederate Dead, a shadow nation of sacrificed lives” (2008: 83). By employing this particular trick, giving no particular attention to the Union loyalties of the dead and allowing some glorification of Confederate soldiers, the authorities responsible for Ball’s Bluff at the state and regional levels have relegated the actual cause of the war and the southern role in fomenting it to an incidental fact. Instead, they actively focus attention on what Faust describes as an elegiac understanding of “shared suffering” (Gilpin Faust 2008: xiii) in the Civil War. The final tally of wins and losses for both sides has become secondary to the simple goal of remembering the war. With its numerous and attentive visitors, the South somehow lost the war yet won the story.

34 The story of Fort Stevens does not appear to explicitly address race. This is, of course, not coincidental. Like Ball’s Bluff, it has been memorialized in such a way that caters to the sensibilities of those who support it—except that in Washington, DC, there seems to be little local support for its preservation. Unfortunately, Battleground National Cemetery is perhaps best read as a cautionary tale. It is too late to go back in time and prevent the encroachment of urban growth. Battleground National Cemetery sits now in a densely populated area, and thus is in fact more accessible than Ball’s Bluff. Neither have other neighbouring attractions to draw visitors, yet Ball’s Bluff does just that. Compelling federal narratives exist: the Civil War can be told as the tale of aggressively pro-slavery Southern states, mounting an army and fighting their own government in an illegal bid to secede.

35 Yet an occasional injection of federal money alone will not bring cultural meaning to a given space. Others have stepped in to commemorate the Civil War in ways that speak more directly to the residents of DC’s predominantly Black neighbourhoods. The African American Civil War Memorial and Museum, for example, pays direct tribute to the U.S. Colored Troops in the Civil War. Yet these commemorative efforts are privately funded, no matter how well curated they may be. The fact that individuals and private organizations gather together to fund commemorative sites demonstrates their importance to some people. A federally funded site, in contrast, is definitive and declarative proof that, to the government, its legacy should matter to everyone. Here, preservation failed. Yet government at federal, state and local levels can have a profound influence on both historic preservation and cultural memory. There is no statue, no poem and no artificial holy site that can recreate the mystique of an original location, where actual things happened to actual people in the name of secession and slavery. Whereas all memorial sites, cemeteries included, have sharp social and political angles, the actual fact of death and violence at a given spot are indelibly true. There is no substitute for a battlefield cemetery. There is no denying the reality of the Civil War—its magnitude then and its implications today—in a place at which it actually occurred. The great risk in allowing cemeteries like Battleground to fade into obscurity is that we allow the actual facts of the war to do the same.

36 Every locality continuously reinterprets the meanings of such tragic loss on such a remarkable scale. No current narrative is the definitive one. Through engaged preservation, the federal and city governments in Washington, DC, can visibly declare their memories of the bloody fight that led the country to Emancipation and look squarely at its legacy today. Clearly, there is national demand for it. There is local demand, too; the passionate safeguarding of Ball’s Bluff in Northern Virginia proves as much. The Civil War provides a narrative by which Americans can come to better understand themselves as individual families or towns and as compatriots today, living in close proximity to neighbours descended from wildly different lines. The darkness of war belies its ability to reaffirm the role of government as an arbiter of growing equality and our responsibility to demand it—and to speak, constantly if quietly, on the nature of our collective historical identity.

37 In my case studies, the lens through which residents of a predominantly Black neighbourhood in Washington, DC, understand Civil War spaces offers a sharp contrast to the understanding held by the mostly white residents of suburban Virginia, even though the war histories and spaces themselves are strikingly similar. The interactions of both groups are shaped by exceedingly modern forces: accessibility, interpretation and the allocation of financial resources. It is our contemporary ownership today of this lethal period in history that dictates our very conceptions of its spatial and physical occupation of our communities. The war’s physical presence can comment on government, race, violence, urban planning and myriad other themes; the flavour of that dialogue between living neighbours and the nearby Civil War dead is based upon the perceptions of the living. The dead are capable of near-limitless commentary, but it is the living who edit the script.

Thanks above all to Dr. Elaine Peña and the American Studies Department at The George Washington University. Craig Allen and Will Murtha provided insightful commentary at important junctures; Danielle Witt tolerated the Civil War takeover of shared space; Joan May, as always, offered unyielding encouragement; Ethan, Tracy, Keegan and Addison have supported every adventure; and Ed, for everything.