Furniture in Public Collections in Canada / La Collection Nationale de Mobilier

Musée des Beaux-Arts de Montréal

1 The furniture collection at the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Montréal comprises some five hundred items of European and North American origin, reflecting the evolution of styles from the late Gothic period to the twentieth century.

2 These holdings include a large portion of the extensive Decorative Art Collection which was started by one of the museum's greatest benefactors, F. Cleveland Morgan. Many of the items in the furniture collection were purchased over the years through the generosity of Mabel Molson.

3 The oldest pieces in the collection are a group of chests with carved Gothic tracery panels, one of which is early fifteenth-century French. The others are slightly later in period — a mid fifteenth-century Florentine cassone whose tracery roundels are bordered with geometric wood inlays and an early sixteenth-century Spanish coffer from Castile that combines Gothic tracery decoration with polychrome-painted leather panels. A very rare English counter table, ca. 1550, is carved with parchemin panels and retains some of its original polychrome-painted decoration.

4 The classically-derived architectural ordering of Renaissance buildings was reflected in their interior furnishings. A mid fifteenth-century Italian credenza with intarsia decoration and a smaller credenza from the end of that century with applied Ionic pilasters are two such examples in the collection.

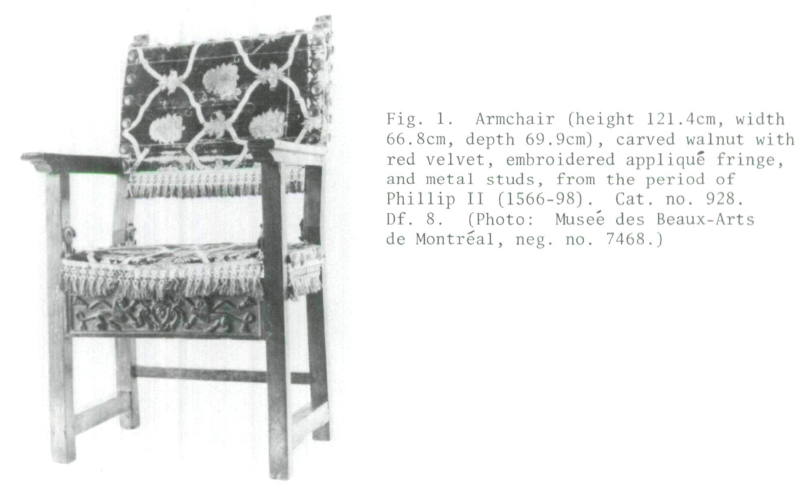

5 From the same period in France comes a group of two-tiered armoires, again with architectural elements, door panels and cornices carved variously with mythological figures in the style of Jean Cousin and grotesque carvings in the style of Jacques Androuet Du Cerceau. A contemporary chair, supported on columnar legs, is fitted with an elaborately carved front seat rail, again in the style of Du Cerveau. In 1928 the museum purchased a number of Spanish chairs (see fig. 1) and trestle tables from the Arthur Byne Collection of Madrid. These exhibit the evolution from plateresque through herreresque to churrigueresque styles typical of Spanish furnishings from the Renaissance to the baroque period.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 16 Classically-derived architectural details appear on English furniture at a later date than items from the continent. A pair of oak chairs, ca. 1620, have arcaded panel backs that derive from designs like those of Hans Vrederman de Vries published sixty years earlier. Certain concessions to comfort in chair design made their appearance with the addition of upholstered seats and backs as seen on two chairs dated ca. 1660-70. These retain their original Russia leather covers. A sleeping chair with an adjustable back, from the same period, is upholstered in contemporary needlework. Certain design elements were retained by provincial craftsmen long after their currency with city folk, as is evident on a hall cupboard that is dated 1690 but which exhibits strapwork and lunette and scroll carving fashionable fifty years earlier. From the same period as the hall cupboard, but more up to date in style, is a fine side chair whose back, stretcher, and legs are elaborately carved with the scroll and bandwork seen in the designs of Daniel Marot. This type of chair was the precedent for a simpler version in ebonized wood made in Boston ca. 1700-25. Dutch influence, reflecting contemporary political events, can be seen in the elaborate floral marquetry of an English walnut chest on stand. The museum also possesses a Grinling Gibbons overmantle carving from Cassiobury Park in Hertfordshire, England.

7 Chinese influence in the design of Queen Anne period chairs is apparent not only in their shape but also in the decoration of a lacquered example. This classic Queen Anne form is seen also in a version from Ireland made of walnut veneered on oak, on two examples from the Netherlands which are decorated in marquetry, and on another example veneered in burl walnut and probably made about 1730 in what is now northern Germany. This Queen Anne style persisted within the context of country or vernacular furniture, as is apparent on a Quebec chair, a rare example made at the end of the eighteenth century. Among other examples of Queen Anne furniture in the collection is a magnificent bureau secretary in burl walnut, with mirror doors enclosing an elaborately-fitted interior.

8 When English furniture makers in the 1730s and 1740s began to exploit the possibilities of the rococo style then current in France, they often grafted ornamental details onto basically traditional forms. The museum possesses several examples of English rococo furniture after published designs by such artists as Matthew Darly, Ince and Mayhew, Manwaring, and Matthias Lock, as well as examples loosely described as being in the Chippendale style. Among these are two chairs — one from Boston, the other from New York — which exhibit the influence these English pattern book designs had .on craftsmen working in North America. The English examples of rococo furniture include a tripod tea kettle stand and a candlestand, the latter having a Chinese-style fretwork gallery. Pierced fretwork in the Gothic style adorns the cornice of a fine Georgian breakfront bookcase made in plum pudding mahogany.

9 The museum possesses a small but representative selection of eighteenth-century French furniture. This includes a fine Louis XV fauteuil a la Reine by Jean-Francois Mayeux. Three outstanding armchairs by Sulpice Brizard exhibit design features and details, such as the colour of the original gilding, that were in vogue during the early phases of neo-classicism that swept Paris in the late 1750s and 1760s. These chairs may be dated to about 1765. Somewhat later in date are a pair of gilded marquises in the style of Jacob and a fine painted bergère by Gailliard that can be dated ca. 1780. A small, late Louis XVI commode by Ohneberg, of ormolu-mounted mahogany, exemplifies the vogue for this wood which was more commonly used in England at the time. This crosscurrent of influences can be seen with English neo-classical furniture in the collection, most specifically on a pair of Adam-style gilded armchairs and a settee recently attributed to the shop of John Linnell — all of which are English translations of French neo-classical design vocabulary.

10 The design of a tambour-top desk, formerly in the possession of Loyalist Sir John Johnson, was taken almost line for line from plate 67 of Hepplewhite's The Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterers' Guide (1788). The design propounded by Thomas Shearer, Hepplewhite's contemporary, can be seen in a large mahogany sideboard from England and in an exceptionally fine dressing chest of drawers attributed to the area of Charleston, South Carolina. Painted decoration became very fashionable in the latter decades of the eighteenth century as exemplified by a polychrome-painted, Hepplewhite cabriole armchair and a black-lacquered Sheraton chair replete with neo-classical motifs painted in grisaille and outlined with gold striping.

11 The influence of English styles on American cabinetmakers persisted well into the nineteenth century. Two examples from the federal period, in the Sheraton style, are an important dining table from New York, ca. 1810, that compares favourably with known examples by Duncan Phyfe, and a small sewing table. The latter is attributed to the Boston area because certain details, particularly the fine turning of the legs, correspond exactly to those seen on furniture by the noted Boston cabinetmakers John and Thomas Seymour.

12 The finest example of English Regency period furniture in the collection is a pianoforte (fig. 2), in rosewood, mahogany, ebony, and inlaid brass, that bears the label of its maker-dealer, Astor and Horwood, London. It dates from ca. 1815 and it is an early example of the so-called Grecian style that persisted well into the mid-century. Evidence for this can be seen in a channel-back wing chair whose design is identical to one published by W. Smee and Sons in 1850. By about this time, however, several other stylistic revivals were manifest in the field of furniture design. Often disparate stylistic elements were juxtaposed in single pieces such as a parlour chair derived from examples published in Blackie's Victorian Cabinet Maker's Assistant of 1853. This combines Renaissance and nineteenth-century French decorative motifs. New technologies made possible the manufacture of papier-mâché furniture items such as a chair and a sewing table that are examples of the rococo revival style. The idea of molding a synthesis of materials to a desired shape was obviously one precedent for chairs developed one hundred years later by such designers as Eames and Saarinen, whose designs are represented in the collection.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 213 The Art Deco style current in Paris between the two world wars is often considered to be the last of the traditionally-based styles of decoration. Examples from this period include two side chairs (see fig. 3) of a Chinese simplicity that bear the stamp of Atelier Martine, the interior design branch of Paul Poiret's fashion empire. In his capacity as a promoter of furniture design, Poiret was influenced by the debate in Germany and Austria on the merits of machine-made vs. hand-crafted objects. In these chairs Poiret opted for the latter solution. The possibilities inherent in machine production were investigated by the artist-craftsmen of the Bauhaus and the museum's cantilever chairs designed by Mies van der Rohe and Marcel Breuer bear witness to this fact. Curiously, however, the museum's own examples of furniture designed by Mies for the 1929 International Exhibition in Barcelona, which have a machine-made look about them, are primarily handmade items.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 314 Technological advances that were by-products of war-time production in the 1940s made possible the Games and Saarinen furniture noted above, and new methods of spot welding made possible the furniture designs of sculptor Harry Bertoia in the collection.

15 The museum's holdings of Chinese furniture are small but important. They comprise a throne, K'ang table, and altar table all executed in incised poly-chrome lacquer on a red ground. Certain iconographical details in addition to the five-claw dragon motif have led scholars to state that these eighteenth-century pieces were part of the furnishings of the Imperial Palace in Peking. The single item of Japanese furniture is a very fine nineteenth-century, roll top pedestal desk, executed in a variety of classic Japanese makie lacquer techniques. The form of the piece, however, suggests that it was made for the European market.

16 The first acquisitions of Canadian furniture were made in 1932. Important items made in New France include a rare seventeenth-century gate-leg table in the Louis XIII manner, and a contemporary armoire with losange-carved panel doors. Perhaps the outstanding piece in the Canadian collection is a twotiered buffet from Lotbiniere County, Quebec, with carved and molded decoration in the Louis XV manner (fig. 4).

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4