Exhibition Review / Compte rendu d’exposition

Dutch New York Between East & West:

The World of Margrieta van Varick

Organizing Institutions: The Bard Graduate Center for Decorative Arts, Design History and Material Culture and the New-York Historical Society

Venue: Bard Graduate Center for Decorative Arts, Design History and Material Culture

Curators: Marybeth De Filippis, Deborah L. Krohn and Peter N. Miller

1 The exhibition Dutch New York Between East & West: The World of Margrieta van Varick was held from September 18, 2009, to January 24, 2010, at the Bard Graduate Center for Decorative Arts, Design History and Material Culture (BGC) in New York City. Co-organized by the BGC and the New-York Historical Society (N-YHS), the impressive display of early modern material culture was organized as part of the statewide recognition of the 400th anniversary of Henry Hudson’s North American exploratory voyage and the legacy of the Dutch in New York. Indeed both the exhibition and its catalogue proved to be major contributions not only to the quadricentennial celebrations but also to the recently expanding body of literature examining Dutch colonial history.

2 New York has had a long tradition of public displays in recognition of historical milestones. In 1909, the Hudson-Fulton celebrations in honour of the shared tercentennial of Hudson’s arrival and the centennial anniversary of Robert Fulton’s first successful commercial application of the paddle steamboat also provided an opportunity to demonstrate the triumphs of New York City, highlighting the city’s aspirations as well as greater national ambitions of the time (Avena and Marostica 2008). Despite often being excluded from the larger narrative of American history, the role of the Netherlands in the USA’s foundation was emphasized during the celebrations, in part due to the re-visioning of Dutch colonial participation, encouraged by a “Holland mania” that was spreading throughout the country (Stott 1998). Among the numerous parades, pageants and historical displays, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City held two major exhibitions. Displayed from September 20, 1909, to November 30, 1909, The Hudson-Fulton Celebration Paintings by Old Dutch Masters included furniture, objets d’art and 145 paintings by artists such as Rembrandt van Rijn, Frans Hals, Johannes Vermeer, Jacob van Ruisdael and Aelbert Cuyp, culled from the collections of prominent New Yorkers such as Henry Frick, J. P. Morgan, Charles Schwab and George W. Vanderbilt. The second part of the Hudson-Fulton Celebration exhibition displayed American visual and material culture from the early 1600s through to 1825. Among the important legacies of this exhibition was the relatively new curatorial organization of objects by form and period. According to Thomas J. Schlereth, 1909 and 1910 were “watershed years for material culture studies in the American decorative arts” in particular due to this exhibition, which is now considered the “first nationally recognized exhibition to present American furnishings to the public” (1982: 14).

3 Museum practice and display conventions have changed drastically in the hundred years separating New York’s tercentennial (1909) and quadricentennial (2009) exhibitions. Until rather recently, displays of domestic material culture have been typically arranged as period rooms. While some institutions like the Museum of the City of New York, with their permanent display of New York Interiors: Furnishings for the Empire City still follow this model, others like the Albany Institute of History & Art and Crailo State Historical Site have rearranged their early Dutch colonial collections to avoid giving the impression that such objects would have existed together as a furnished room. Notably, Dutch New York Between East & West was held in the BGC Gallery, a space that despite its educational institution affiliation maintained the domestic feel of the 19th-century brownstone housing it on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. However, although this space could have been used to reinforce an in situ experience, allowing viewers to imagine the objects arranged as in the possession of van Varick, the curators resisted the urge to create a period room style presentation. According to the website, the BGC Gallery has a mandate to display exhibitions that “consider issues and ideas that exist largely outside the established canons of art history,” which stands in sharp contrast to the 1909 Hudson-Fulton Celebration host venue, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, with its canonical status and current penchant for blockbuster shows.

4 Furthermore, unlike the Met, the BGC Gallery is an exhibition space and does not have its own collection. Perhaps while presenting some challenges, this lack of a permanent collection allows for a certain degree of freedom and opportunities to collaborate with other institutions, bringing together new combinations of scholars and objects with each organized exhibition. Arguably the BGC’s 2009 exhibition benefited from its partnership with the N-YHS, an organization with a rich but underexplored collection and the outcome proved to be an equally innovative milestone in the exhibition of material culture. Although conceived under the auspices of a quadricentennial celebration that continues to promote the “discovery” of North America by European explorers in a manner problematic within contemporary post-colonial perspectives, the exhibition demonstrates an innovative approach to curating. It promotes the exhibition of material culture as a self-reflexive process, highlighting the curatorial team’s critical engagement with often ignored objects and equally overlooked histories.

5 Born in Amsterdam in 1649, Margrieta van Varick travelled to the far reaches of the Dutch colonial world, first to Malacca (present day Malaysia), before returning to the Dutch Republic with her minister husband Rudolphus. In 1686 van Varick and her family embarked on another voyage, crossing the Atlantic to settle in Flatbush, New York. Recently acquired by the English, the colony of New Netherland, had been initially established by the Dutch West India Company or Geoctroyeerde Westindische Compagnie (WIC). Even by the time of the van Varick’s arrival, the colony maintained a particularly Dutch culture, with the language, customs and religion of New Netherland persisting despite English rule. Rudolfus ministered to a politically fraught congregation and his wife established a flourishing textile business in a hybrid community, diversified by indigenous and enslaved peoples as well as religious refugees and immigrants from around the world.

6 The will of Margrieta’s husband, Rodulfus van Varick, was drafted in Dutch on October 22, 1686, by William Bogardus, a New York public notary. Nearly ten years later, hers followed an English format scribed by an unknown person, but signed by Margrieta van Varick herself. With the originals now lost, only microfilm images of these exist. In the fall of 2004, then-graduate student Marybeth De Filippis found a copy of the nineteen-page probate inventory of Van Varick’s household and textile shop in the library of the New-York Historical Society. Inspired by De Filippis’ Master of Arts thesis completed during her studies at the BGC, the curators and collaborators used Margrieta van Varick’s will and probate inventory of 1696 as a means of examining her life and culture in colonial New York. The objects displayed in Dutch New York Between East & West serve as the material representations of the ways in which items in local and global trade networks function as tools in articulating and forming identities in the multifaceted social exchanges and performance of gender, class and race roles. Van Varick proves to be a thought provoking example of the increasingly global lives of many women in the 17th century and her inventory and a speculative amassing of the types of objects she may have owned can be viewed as an informative indicator of cultural exchange patterns.

7 Despite extensive research, the curators were able to find very little further documentation of van Varick’s life beyond the will and probate inventory. To bridge these gaps, however, the exhibition draws on extant material culture to represent both the vernacular items and luxury goods shaping her world and defining her lifestyle. With an innovative approach, curators De Filippis and Deborah L. Krohn gathered approximately 170 objects from public and private collections in the United States and the Netherlands. While most come from the collection of the New-York Historical Society, other lenders included the J. Paul Getty Museum, the Museum of the City of New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the American Museum of Natural History, the Brooklyn Museum, Yale University Art Gallery and the Peabody Essex Museum, as well as the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam and the Amsterdams Historisch Museum. The exhibition was organized into five thematic sections, each speaking to a larger historical dialogue teased from aspects of van Varick’s life, as well as exploring the wide range of personal and commercial goods in her possession when she died in late 1695.

8 The Bard exhibition highlights a key problem arising from the creation of an exhibition of objects based primarily on surviving texts. It was appreciated by the curators that some viewers could be uncomfortable with the substitution of extant artifacts—though similar in type—instead of having the exact ones enumerated by van Varick’e executors. Without some curatorial speculation, however, this exhibition would have simply been impossible: had the curators included only objects of an early American provenance as per a more traditional museum model, there would not have been such an extensive display. De Filippis, Krohn and Miller instead took responsibility for performing what Michel de Certeau terms a “historical operation” (1988) to “tease out meaning and wrestle evidence from a recalcitrant past” and make the “sometimes insoluble ambiguities” part of the story they were telling (Krohn, Miller and De Filippis 2009: 1). This curatorial approach questions the purpose of exhibiting material culture: Is it the singularity or authenticity of the object and its register of a particular time and place? Or is it the mnemonic place that it can take within a larger historical narrative?

9 Prominently displayed in the entrance to the exhibition, the inventory was showcased as the literal and theoretical starting point for investigation. It was also here that the visitor first encountered the unique and refreshing approach of the curatorial team. From the beginning, they make visible their research methods, with the inventory presented as a document of historical research and, more importantly, as the cornerstone of a curatorial practice. De Filippis and Krohn’s attention to documenting and considering working methodologies was reinforced by a video interview featured in the introductory room of the exhibition, between BGC president Peter Miller and renowned historian Natalie Zemon Davis. Theoretically, methodologically and physically starting with van Varick’s inventory, what follows in the exhibition space, and through the academic discourse produced, was not an “archaeological reconstruction” of the specific objects listed. With the actual objects lost and accurately tracing them an impossibility, the curators did not try to recreate van Varick`s collection but rather represented the kinds of ceramics, textiles, furniture and utensils that van Varick could have owned.

Display large image of Figure 1

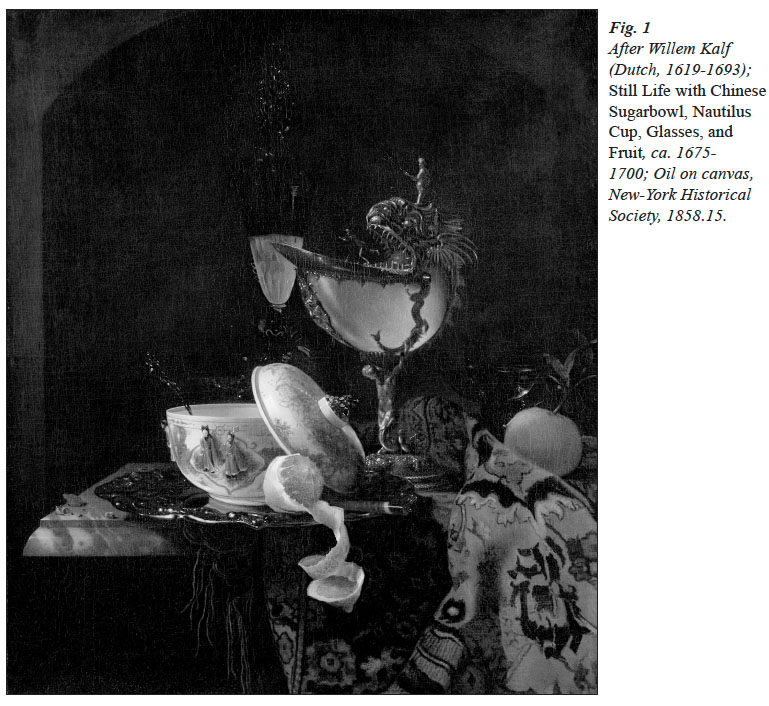

Display large image of Figure 110 After presenting the documents and objects inspiring the exhibition, the next section “Trading Places,” assembled extant material culture to contextualize van Varick’s position within the vast networks of the Dutch trade colonies of the Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie or VOC) and later the WIC. Although limited historical traces of van Varick exist, she was a compelling figure as she was one of very few Dutch women to have lived in both the Dutch East Indies and the Atlantic colony of New York; her possessions reflect her global travels. Maps, globes, textiles, prints and travel accounts, as well as paintings such as Philippus Baldaeus and Gerrit Mosopatam near the Church of Paneteripou (1668) by Johan de la Rocquette and The Castel of Batavia, seen from West Kali Besar (ca. 1662) by Andries Beeckman provided a vivid picture of the locations where van Varick and her relatives lived and where she would have acquired some of the goods listed in the inventory. By pairing the dramatic Still Life with Chinese Sugarbowl, Nautilus Cup, Glasses, and Fruit (ca. 1675-1700) from the workshop of Willem Kalf (Fig. 1) with actual examples of the porcelain (Figs. 2 and 3), silverware, ivory carved boxes, lacquer wares and other commodities being introduced to Europe from the rest of the world, the exhibition masterfully highlighted the ways expanding global trade networks of international exchange and rapid increases in wealth manifested in the intersections of visual and material culture during the 17th century.

11 A second section of the exhibition Dutch New York, narrowed the focus to the Dutch presence in North America, to consider the history of the former WIC colony and the persistence of Dutch culture under English rule. When van Varick arrived in 1686, New Netherland had for more than two decades already been named New York. As many scholars have demonstrated, however, a particular “Dutchness” continued in linguistic, legal, religious, social and, most vividly, material forms. A pair of silver beakers attributed to Jurian Blanck Jr. and owned by Old First, The Reformed Dutch Church of Brooklyn, demonstrates not only the church’s role in preserving and disseminating Dutch culture well after the English arrival but also the Dutch community’s role in early American silver production. Similarly, a brandywine bowl or brandewijnkom by Benjamin Wynkoop (Fig. 4) traditionally used during Dutch kindermaal—a ritual celebrating the birth of a child—attested to the ways in which material culture reflected the continuance of social practices from Dutch patria. Along with the beaver pelt industry that had initiated the Dutch colonization of what would become New York, early silver-smithing would have a profound influence on trade with indigenous communities. Many of the items in this exhibition indicate the material consequences resulting when

These sorts of colonial negotiations are apparent in the documents selected by De Filippis and Krohn to augment the historical narrative of the exhibition. Epistolary articles such as a letter from the WIC directors to Petrus Stuyvesant (1659) and visual descriptions like prints, maps and portraits cleverly illustrated the experience of van Varick and her family at a particular moment of great social flux.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2 Display large image of Figure 3

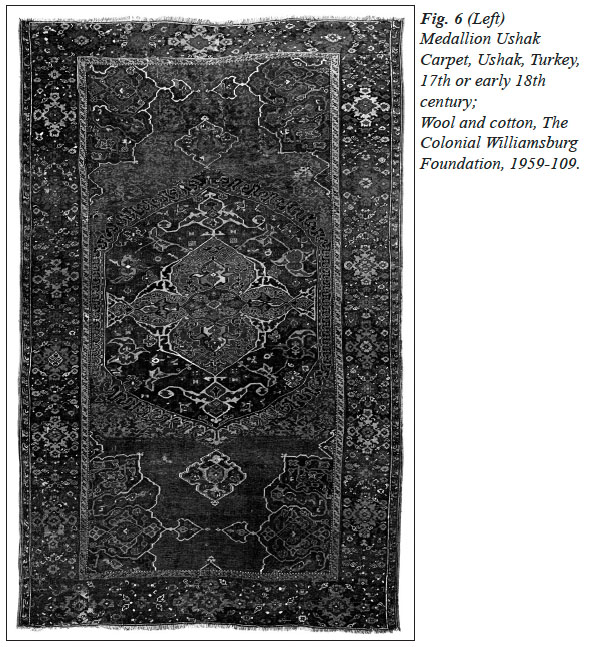

Display large image of Figure 312 Van Varick’s inventory was organized into three categories: items bequeathed to her children (“bequeathed to hur undernamed Children viz”); shop merchandise (“10 ½ yard white flannell”); and household goods (“howsell Goods”). The curators acknowledge the limitations of working with inventories in general, noting that the passage of time and the translation process has rendered van Varick’s inventory a list, signifying classes or types of objects, leaving it impossible to identify specific objects (De Filippis 2009: 2). Rather than ceding to this constraint, the fourth section of the exhibition, “Margrieta’s Inventory: A World of Goods,” included similar representations of the many goods described in the 1696 inventory—furniture, metalwork, textiles, clothing, utensils and ceramics. The imposing walnut, elm and oak kast selected for display (Fig. 5) could be similar to the “Great Chist lockt up” listed at the very beginning of her inventory. Likewise, De Filippis and Krohn included plausible representations of the “finist turkey worky carpet” (Fig. 6), the “silver wrought East India trunk” and “cullerd callico Curtens.” Other items such as the “eleven Indian babyes” proved to be more challenging to interpret. Again reinforcing the curators’ understanding of their role in the act of “translating” Van Varick’s inventory, De Filippis and Krohn provided multiple possibilities to the interpretation of some of the entries. In doing so, they cleverly recoup the process of “connoisseurship” or what they refer to as “historical tact” to “make educated assumptions about what, given the state of our contextual knowledge of contemporary people, places and things, could have been referred to by a document of this sort, written at that location and at that time” (2).

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4 Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5 Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 613 The final section of the exhibition, “The Van Varick Legacy: From Colony to Nation” traced the lasting impact of Van Varick’s presence in what would subsequently become the United States of America. Among van Varick’s descendents were Richard Varick and Marinus Willett, both of whom served with distinction in the Revolutionary War and both of whom went on to serve as mayor of New York City. They are the namesakes for Varick Street in downtown Manhattan and Willets Point in Queens. Perhaps one of the boldest assertions of the exhibition, however, was that van Varick’s legacy was not only political but also material. In 1711, Van Varick’s daughter Cornelia Varick married Peter van Dyck, the acclaimed early American silversmith. In light of this familial connection and the fact that Cornelia received a portion of the bequeathed silverware introduces the possibility that van Varick’s possessions, amassed from around the globe, may have influenced the later history of American decorative arts (De Filippis 2009).

14 As is often the case, the lasting contribution of the Dutch New York Between East & West exhibition is the extensive catalogue that accompanied the ephemeral display of objects. Krohn and Peter N. Miller, who co-edited the publication accompanying the exhibition, poetically describe their search to find van Varick’s voice and put a “face” to the inventory saying:

De Filippis, Krohn and Miller’s project uses a microhistorical perspective to tell the story of a woman and her things. By drawing out narratives from the Japanese silver, Indian textiles, Arabian coins, Chinese porcelains and other entries in the inventory, it becomes quickly apparent how correct Igor Kopytoff was to insist, “[b]iographies of things can make salient what might otherwise remain obscure” (1986: 67). The theoretical scholarship on the social biography of things underpinning this research points further to the role of “biographical objects” with possessions of personal significance disrupting commodity processes (Hoskins 1998: 8). Utilizing the unique opportunities provided by material cultural strategies, the editors are “driven by a desire to recapture the ordinary, the female, the excluded, those whose voices were not recorded in archives or were ventriloquized by their ‘betters’” (Krohn, Miller and De Filippis 2009: 5). Although the picture that begins to emerge presents only a vague image of van Varick that raises more questions than answers, perhaps one of the greatest strengths of the catalogue is the methodological self-reflexivity outlined by the editors. As earlier mentioned, the authors have sought a certain degree of transparency in the curatorial project, keen to note alongside the multitude of important discoveries the reoccurring challenges that appear when dealing with objects from the past and narratives often excluded from official, masculine histories. The exhibition and the catalogue are equally invested in the journey and the destination, with the curators noting the contributions are “as much essays in the problematic of microhistory as they are a search for a seventeenth century shopkeeper” (1).

15 Following the same five divisions of the exhibition, the catalogue includes detailed entries on the 171 items displayed in the exhibition. With its full colour images and extensive research, the weighty catalogue is itself an attractive object. For the curators and editors of the catalogue, their central motivation is at the root of material culture studies—“how possessions gain and change meaning by being possessed, and how the possessor imparts meaning to things even as she might be changed by them” (2009: 9). These entries are all substantial pieces—seven longer thematic essays in addition to contributions by prominent scholars such as Titus M. Eliëns, chief curator of applied arts at the Rijksmuseum and Ebeltje HartkampJonxis, curator of textiles at the Rijksmuseum. Here, early modern utilitarian objects garner as much attention as prints, paintings and documents regularly consulted by historians, to fill the lacunae of English-language scholarship on everyday items produced and consumed within early modern Dutch trade networks.

16 Along with the extensive catalogue entries, the essays demonstrate the ways in which a microhistorical investigation of one particular woman can develop into broader histories and speak to the multiple interpretations provided by such rich historical documents as those left by van Varick. In the first thematic essay inspired by the inventory, Dutch historian Kees Zandvliet outlines the context in which van Varick travelled, lived and traded. He briefly describes the political and economic conditions that allowed for the Dutch to emerge at the fore of a global trade empire. Zandvliet also discusses the structuring of the VOC and the role of merchants like van Varick’s uncle Abraham Burgers and her first husband Egbert van Duins in Southeast Asian commerce. When writing of the absolute rule of the VOC in the colonies (they were granted permission to enter into treaties and controlled the official publications), he is careful to note that the Dutch did not have “aspirations to moderate the local population” or “take military action on the basis of moral outrage” especially when it came to religion (18). According to Zandvliet, it was not unique that van Varick returned to the Netherlands with such an array of Asian luxury items. What distinguishes her travels from that of other Dutch people active in global trade networks, however, was the subsequent departure for New York with her belongings, where trade continued to be regulated by the VOC’s Atlantic counterpart, the WIC. As demonstrated by Zandvliet, van Varick’s vast travels allow for a comparison between the experience of people engaged in some way with the VOC and the WIC. His essay reveals van Varick and her goods as a “rare illustration of the expanse of the Dutch global network” (22).

17 Historian Els Kloek further outlined the role of women, contributing a chapter entitled “Women of a Seafaring Nation: A Chapter in the History of the Dutch Republic, 1580-1700.” Despite the lack of information on the involvement of women in overseas trade, Kloek presents several examples of women’s lives that clarify the “impact influence of colonial expansion projects upon women in the Netherlands” (26). She points out that it is important for early modern scholars examining global expansion to position the lives of colonial women against those of the Dutch Republic (26). Kloek describes the contrast between the historicized status of women in the Republic and the actual lived experience, with the legal requirements of guardianship not always followed, particularly in distant colonies. She explains how the openbare koopvrouwen (public tradeswomen) construct allowed women to conduct trade in their husbands’ absence and created varying degrees of autonomy (27). While providing examples of the auxiliary roles of women in the overseas trade of the United Provinces, Kloek asserts that the stereotype of the “steadfast Dutch housewife” persisted, with her “commanding presence in the home” and assertive “enterprising in everyday life” attitude such women were most often encouraged to remain at home (38).

18 In chapter 3, Marybeth De Filippis, curator of the exhibition and one of the first scholars to thoroughly research the material goods of van Varick, presents an inventory as a genealogy, revealing webs of personal and professional relationships. For De Filippis, van Varick “represents an enigma of the inanimate and the animate, of possessions and people, and how one illuminates the other” (41). She uses translations of four key manuscripts to trace van Varick’s early life in the East Indies: the registers of the Dutch Reformed Church in Malacca, ca. 1660-1680; a letter from the VOC’s factory in Bengal to its governing board—the Heren XVII in Amsterdam—identifying her first husband Egbert van Duins as a participant in trade; a 1674 letter indicating her uncle Abraham Burger’s supervision of a shipment of Japanese goods from Malacca; and a report by Balthasar Bort, the former Governor of Malacca outlining van Varick’s second husband’s yearly allowances. These texts not only speak to the global nature of van Varick’s possessions, but also place her directly in the contact zones of Dutch colonial expansion (Pratt: 1992). Letters from van Duins to VOC directors in Persia and Surat establish contact with entrepots from which van Varick may have acquired her “arabian silver Monny,” gold “duccates” and “turkey work” carpets, and the conduits along which “callico” and “Chint flowered” carpets travelled (Fig. 7). These documents offer clues to the origins of Van Varick’s diverse collection of objects, but only provide partial answers to De Filippis’ questions. Thus, they underpin the extensive research that went into the exhibition, asking, as De Filippis initially did: “what [these objects] were, how she happened to have them and what this tells us about the hemispheres of the Dutch world in which she lived” (41).

Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 719 Citing a late-18th-century letter in which the writer noted “Our New World gains in strength, riches, and a happy state beyond belief” (55), independent scholar Jaap Jacobs discusses the ways Dutch culture endured in New York long after the English first acquired the colony in 1664. He suggests that in the late 17th century a Dutch identity may have been more apparent in the former colony than even in the Republic, as inhabitants were eager to define their “Dutchness” against the “otherness” of the English colonists (55-56). The “autonomous cultural development” of a Dutch-American identity was influenced by several complex conditions. Although there was continuous contact with patria, especially in the form of commodity exchange and religious doctrine, by the third quarter of the 17th century immigration virtually stopped, creating an autonomous cultural development. While not ethnically homogeneous, Jacobs posits that New Netherland to a large extent was Dutch

“A Portrait of Women in Seventeenth Century New York” by Joyce D. Goodfriend, describes what life would have been like for van Varick as one of the approximately 3,500 women in and around New York at the time of her arrival. She describes a heterogeneous community of Dutch, English, French, Jewish, African and indigenous women linked in varying ways to Atlantic trade networks (67). Despite their ethnic differences, Goodfriend notes that, with the exception of enslaved Africans (and I would also add Native Americans), many women shared similar core experiences as the “wives, mothers, and mistresses of households” that would shape their material existence (68). As New York had high levels of slaveholders, Goodfriend explains colonial women had a different, more complicated relationship with domestic servants than their counterparts remaining in the Republic (70). She does admit that recent scholarship has not fully explored how the use of slave labourers in early New York “shaped the domestic experience of female New Yorkers, white and black” (71). Goodfriend argues Dutch women in the colony, as in the United Provinces, “subscribed to an ideal of female competence and autonomy” and “often enjoyed a good deal of latitude in the marketplace and the courts” (71).

20 David William Voorhees, director of the Papers of Jacob Leisler Project, contributes a chapter on the rural community of Flatbush, where the van Varick family settled. He illustrates the village as it would have been at the time of their arrival, with roughly 500 people and plenty of what one contemporary resident described as “good farms” (84). The majority of the buildings were farmhouses of medieval Netherlandic construction, “small, cramped, and dark, sweltering hot in summer and freezing in winter” (85). Voorhees notes, however, that despite the “rustic setting” the van Varick’s community was closely tied to the international economy, supplying grains for the West India trade (85) and religious as well as political circumstances. Furthermore, Rudolfus van Varick’s position as a minister in the Dutch Reformed Church illuminates the role of religion in the community. Alternating with another minister, Henricus Selyns, van Varick serviced the congregations. Rudolfus noted of his congregation: “All are able men and in harmony. The Reformed Church of Christ lives here in peace with all nationalities” (87). Vorhees notes that despite his “idyllic portrayal,” tensions were increasing on Long Island and van Varick would soon be embroiled in the uprising later known as Leisler’s Rebellion.

21 Finally, in an important contribution to material culture studies, Ruth Piwonka, takes up the van Varick inventory as an important genre in and of itself, exploring the conventions and meanings of such documents and comparing it to other similar texts. She notes that while in many ways typical of women of her time, van Varick’s diverse collection of household, shop and personal goods outlined in her probate inventory is indicative of van Varick’s extraordinary global life (99). Piwonka describes the legal context for the creation of wills and inventories at the time and the lasting implications for women’s material legacies. She also discusses at length the importance of reading an inventory as a reflection of a life, as in the case with van Varick. This methodology proves most rewarding when records and objects are set against a biography (104). Despite the challenges (discrepancies in terms, lack of full descriptions, nonspecific nomenclature), Piwonka compares the itemization of van Varick’s possessions to others of the time. Because of its relatively detailed descriptions and valuations, van Varick’s inventory comprises an important standard in which scholars can compare and contrast no longer extant material cultures. Ultimately, Piwonka determines that van Varick was much like her other colonial counterparts in terms of shop merchandise, but her personal possessions reflected a uniquely large quantity of luxury goods—textiles, silver and porcelain—from her travels in Southeast Asia.

22 Despite the abundance of textiles listed among van Varick’s household and shop holdings, the exhibition contains a surprisingly limited number of such items. Due to everyday use, very few textiles from the colonial period survive. This lack of extant textiles from the early modern era reflects not only the ephemeral materiality of cloth but also its key utilitarian importance as fabrics were often so valuable they were reused and recycled in a variety of ways (Hood 2003: 8-9). With the vast number of collections accessed by the curatorial team in both the United States and the Netherlands, it is surprising that the exhibition did not include more works demonstrating the van Varick’s varied holdings. Similarly, despite the detailed catalogue entries, the publication accompanying the exhibition lacks an essay focused on the role of textiles in Atlantic trade. Both the exhibition and the catalogue focus heavily on metal goods—drinking vessels, utensils and even toys—items that have survived most frequently intact. Perhaps this is one of the ways the exhibition can serve to stimulate scholarship on the material production of the Dutch colonies, which, due to the lack of surviving objects, architecture and documentation are notoriously difficult to study.

23 Also included in the catalogue is a transcript of the conversation between the editor Peter Miller and Natalie Zemon Davis, a video of which was displayed in the exhibition. Speaking from her own experience working with inventories, Davis suggests lines of questioning and ways of approaching not only the information available, but also methods for engaging with the gaps in documentation presented by vernacular histories. In the transcribed version of the interview included in the catalogue, Miller defines microhistory as “narrative reconstructions from archival sources, often intended to record other matters such as the lives of individual people of no great account and therefore able to shed light on ‘ordinary’ conditions for ‘ordinary’ people” (127). Echoing Davis’s discursive approach, the exhibition is not framed as the final word on the life and objects of van Varick, but rather as an invitation to further scholarship. This dialogue is intended to, and undoubtedly will, provoke a greater inquiry into the ideas and issues raised not only by the curators of the exhibition, but also the relationships that have been formed through the assembling of such an array of diverse and powerful material representations of centuries of cultural exchange.

24 The Dutch New York Between East & West exhibition and catalogue are both major additions to scholarship on colonial New York and the perseverance of Dutch culture despite the English takeover and subsequent American Revolution. Reflecting an “intersection of curatorial and academic approaches,” the research methods and critical approach employed serve as a model for innovative ways to display and discuss material culture (Krohn, Miller and De Filippis 2009: 7). More importantly, this project amasses a diverse grouping of worldly material culture, thus exemplifying innovative ways to tease full and vibrant portraits from often flat and dull documents. The diverse objects featured are rarely exhibited together, but both the exhibition and catalogue provide much-needed snapshots that continue to shed light on an under-examined aspect of North American history (51).

25 Like its precursor, the 1909 Hudson-Fulton Celebration, the Dutch New York Between East & West exhibition and catalogue are also important contributions to material cultural scholarship. Although the catalogue is all that remains, for several months nearly 200 objects were brought together to tell new stories and to provoke ideas precisely elucidating Schlereth’s emphasis on the potential for exhibitions to “act as a basic display case of evidence often inaccessible to many students. They can also serve as the analytical vehicle whereby material remains are arranged in a new relationship so as to prompt a new interpretation about the past” (1982: 14). “Unlike books,” Schlereth claims, “exhibitions bring like-minded students of the object together physically in one place to compare notes, to gossip, to exchange ideas, and to meet each other” (ibid.). The catalogue for Dutch New York Between East & West: The World of Margrieta van Varick will continue to connect people and places across time and space and inspire a further investigation of things.