Articles

The Megaphone as Material Culture:

Design, Use and Symbolism in North American Society, 1878-1980

Résumé

Cet article examine l’utilisation du mégaphone (porte-voix) en tant qu’objet de communication et en tant que symbole culturel sémiotique en Amérique du Nord entre la fin du XIXe et le début du XXe siècle. Cette analyse permet d’avancer que l’on peut établir une corrélation entre les modifications techniques du mégaphone et les changements prononcés chez ses utilisateurs, dans son usage et dans sa signification culturelle à travers le temps. N’ayant que des possibilités de communication limitées, le mégaphone des débuts jouait un rôle prééminent dans la structure de pouvoir patriarcale et la culture des loisirs de l’ère victorienne, en tant qu’instrument sexué et exclusif, qui conférait savoir et importance à ses utilisateurs majoritairement masculins. Cette association avec le pouvoir et le statut privilégié, cependant, s’est amenuisée au début de la période d’après-guerre. Répondant aux progrès spectaculaires du design et de la technologie et conjointement à une polarisation sociétale grandissante, le successeur moderne du mégaphone des origines s’est vu attribuer de nouvelles significations culturelles, antithétiques de celles de l’ère victorienne, et a évolué, en un symbole culturel polarisé, en un objet politisé et démocratisé utilisé par un ensemble diversifié d’acteurs sociaux, dans le but à la fois de maintenir et de contester le statu quo.

Abstract

This article examines the ways in which the megaphone was utilized as an object of communication and as a semiotic cultural symbol in North America between the late 19th and late 20th century. Through this analysis, it argues that a correlation can be established between technological modifications to the megaphone and pronounced changes in its users, use and cultural meaning over time. Equipped with limited communicative capabilities, the original, vintage megaphone occupied a prominent role in the patriarchal power structure and culture of leisure of the Victorian era as a gendered and exclusive instrument that accorded knowledge and stature to its primarily male users. This association with power and privilege, however, grew more tenuous by the early-post-war era. In response to dramatic advances in design and technology and in conjunction with growing societal polarization, the modern successor to the original megaphone became ascribed with new cultural meanings antithetical to the Victorian era, and evolved into a polarizing cultural symbol as a politicized and democratized object utilized by a diverse set of social actors to both enforce and contest the status quo.

1 The megaphone has occupied a constant, yet nebulous, position in the cultural landscape of North America for more than one hundred years. Originally conceived by Thomas Edison as a cone-shaped device which would improve communication by amplifying the human voice, the modern megaphone continues to function as intended.1 However, this sense of continuity cannot be extended either to the specific use of the object over time or to its semiotic cultural significance as a mode of communication. This article explores the reasons for such change by discussing and differentiating the primary ways in which megaphones have been employed as communication devices in North American society between the late 19th and the late 20th century.2 Referencing the New York Times and the Globe and Mail, newspaper accounts demonstrate a noteworthy shift in the use and symbolism of the megaphone following the Second World War.3 This article further argues that such changes sprang from both escalating postwar political and social tension and design improvements, which modernized the megaphone and strengthened its communication capabilities midway through the 20th century.

2 In the field of material culture studies, the megaphone has received scant attention either from scholars specializing in technology or those with a general interest in the megaphone.4 This oversight is especially glaring since material culture is concerned with objects as semiotic cultural symbols. Jules Prown, art historian and arguably the dean of material culture studies, explicitly notes the potential of objects to “transmit signals which elucidate mental patterns or structures” and “serve as cultural releasers … [which] can arouse different patterns of response according to the belief systems of the perceivers’ cultural matrices” (1982: 6). Similarly, historian E. McClung Fleming, another prominent material culture scholar, remarks that an object functions as a “vehicle of communication conveying status, ideas, values, feelings, and meaning” in relation to the culture in which it is subsumed (1974: 158). A third noted scholar of material culture studies, Henry Glassie, argues that an object must be interpreted as an “affecting presence, the perpetual, mythic enactment of a culture’s essential structure” (1988: 86). As a device explicitly imbued with social functions, the megaphone constitutes an object, as defined by Prown, Fleming and Glassie, from which one can discern meaning about broader aspects of culture. More specifically in this case, the megaphone illustrates how people reacted to, and benefited from, improvements in communication in modern North American society.

3 As communication devices, megaphones are typically used by one person to address an individual, group or larger audience for any number of purposes—social, political or in emergency situations, for example. Design and aesthetics aside, a megaphone almost always includes a handle by which the device is held. The handle is located on the narrow end of the conical instrument and generally held by the user so as to position it on the underside of the cone, facing the ground. Speaking into the smaller end of the cone, the user directs the megaphone outward toward the audience enabling the sound to be amplified as it travels from the narrow through the widened circumference at the other end of the cone. The audibility and clarity of the generated sound depends on the speaking characteristics of the user, although volume-control features eventually became part of megaphone design.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 14 While the strength of the resulting sound is contingent on the actions of the user, it is even more dependent on the technological capabilities of the megaphone itself. In other words, design is crucial to the success of the amplification process. Edison’s original conceptualization of the megaphone (Fig. 1) was made from tin, wood or papier-mâché and was thus relatively light and easy to handle. As its most distinguishing feature, the cone structure successfully amplified the voice of the user, but the resulting sound—even if the user chose to shout—could not effectively travel more than one or two hundred yards and, as noted in the Science News Letter, permitted “only the people in front of the announcer to hear” (1926: 6). Notwithstanding these limitations, the original megaphone as conceived by Edison represents an ingenious object which brought new possibilities to human communication.

5 Edison’s model, however, was not destined to remain immutable over time, as the megaphone benefited from the technological changes that characterized much of the 20th century. Close inspection of another, distinct megaphone reveals significant technological modifications which served to improve and enhance its capabilities. This megaphone was examined primarily by following the steps proposed by Prown (1982) and Fleming (1974) in their respective studies, both of whom outline a theoretical model for conducting objectbased studies in the field of material culture. In terms of design modifications, the more modern megaphone (Fig. 2) is composed of entirely different materials in that it is made of plastic, rather than tin, wood or papier-mâché. Second, it is an altogether larger device, especially in terms of the circumference of the wider end of the cone, which ostensibly increases its capabilities for amplifying sound. Third, and most importantly, this megaphone is transistorized, meaning it has been constructed to operate with the aid of batteries.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 26 One must activate the transistorized megaphone by pressing an on/off button located directly below the area into which the user is supposed to speak. Activation and subsequent usage produces a powerful amplified sound. In addition, there is another knob that controls the output volume level, allowing the user to manipulate the resulting sound to an almost inaudible or, conversely, deafening pitch. Moreover, two other buttons—an alarm and music playback—produce high-pitched noises without requiring an accompanying human voice, thereby providing another, novel way of using megaphones for social purposes. These transistorized features cumulatively increase the power of the modern megaphone to communicate by radically amplifying the human voice far beyond the capabilities of the original megaphone, thus allowing the sound to remain audible across much greater spaces.

7 It is clear that the contemporary transistorized megaphone no longer resembles its former model in size, shape, colour and material, and that it also constitutes a far more powerful and formidable device than its predecessor. Having established the evolution in design, it is important to consider whether any correlation can be established between these technological modifications and changes in users, use and cultural meaning over time. This article argues that such a correlation is apparent by examining how the megaphone was utilized as an object of communication and as a semiotic cultural symbol in North American society in the decades that both preceded and followed the design overhaul. More specifically, the original, vintage megaphone occupied a prominent role in the patriarchal power structure and culture of leisure of the Victorian era. As such, during that time, it constituted a gendered and exclusive communication device that accorded knowledge and stature to its primarily male users who relied on it to both instruct and entertain.

8 Changes in users, use and cultural symbolism occurred following the emergence of modern electronic modes of communication made possible by the invention of the transistor and its amplification of sound. In response to dramatic advances in design and technology and in conjunction with growing societal polarization, the modern megaphone was ascribed with new cultural meanings antithetical to the Victorian era. Attracted by the enhanced features marketed in a multitude of advertisements, new users employed transistorized megaphones less for economic and entertainment reasons than for a variety of practical social purposes, one of which was to challenge authority. As women and African Americans used megaphones in greater numbers during the decades of the 1960s and 1970s to protest gender and racial discrimination, the megaphone increasingly became synonymous with opportunity and liberation—enabling one’s traditionally marginalized voice to be amplified and, no less significantly, recognized and respected. Within this fluid context, the modern megaphone evolved into a polarizing cultural symbol as a politicized and democratized object utilized by a diverse set of social actors to both enforce and contest the status quo.

9 Edison’s invention of the megaphone in 1878 coincided with an age of optimism characterizing the Victorian era. Victorian culture revered the development of an increasingly industrialized and urbanized society under the auspices of the market economy, believing it to represent a harbinger of progress and modernity. Jackson Lears (1994), for example, notes the emergence in late-19th-century United States of an “ideology of national progress that merged technological, intellectual, and spiritual development” (110). Within this notion of progress, the burgeoning Victorian middle class highlighted the virtue of hard work as a means of achieving personal satisfaction and economic success. However, rest and leisure were also promoted as a regenerative experience devoid of the demands associated with work.

10 Victor Turner argues that leisure in a market economy represents “freedom from a whole heap of institutional obligations prescribed by the basic forms of … technological and bureaucratic organization” (1982: 36). Victorian society, then, embraced a culture of leisure and enjoyment that operated in tension with the responsibilities and requirements of work. Moreover, it was within this cultural milieu that the megaphone was initially incorporated as a gendered object of communication used primarily by men, as Victorian-era-women were restricted from assuming such a prominent public position by the Victorian cult of domesticity (McClintock 1995). During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, men employed these early megaphones to entertain, instruct and profit from primarily middle- and upper-class audiences interested in experiencing activities thought to be appropriate for status and, in the process, perpetuate their own position of privilege within Victorian society.

11 Generally speaking, the cost of purchasing a functional megaphone in the Victorian era was reasonable by today’s standards. A May 22, 1903, advertisement in the New York Times, from Ingersoll’s Sporting Goods in New York offered a discounted twenty-four inch metallic megaphone with handle for sixty-three cents in U.S. dollars ($15.09 in 2011), reduced from its original price of one dollar ($23.95 in 2011). Subsequent marketing attempts offered equally affordable prices. In the Times on October 18, 1912, Macy’s offered different megaphone models made of wood and metal at a price ranging from twenty-one cents ($4.81 in 2011) to $2.24 ($51.34 in 2011). It can be inferred from this varied price scale that megaphones—whether high-quality or not—were generally affordable and hence accessible objects in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Yet the relative affordability of the early megaphone did not produce a broad, diverse set of users. Denied an equal position in civil society, most women were far less likely than men to utilize megaphones during this period since use on their part would signify civic involvement and constitute a threat to contemporary notions of patriarchy and order.5 One exception, however, was reflected in the growing activism of women’s rights groups, many of which by the turn of 20th century called for the enfranchisement of women. No less adroit than men, these women turned to the megaphone in their quest for the vote. Keetley and Pettegrew (2005:) note that one group of early suffragettes who, in organizing for women’s rights in 1904, “went out into the streets of New York and distributed “Votes for Women” badges, played “Votes for Women” on a hurdy-gurdy in the street, and drove around in a taxi shouting slogans through a megaphone” (145). Notwithstanding its limited use among women and despite its relative affordability, the early megaphone was a medium steeped, for the most part, in exclusivity with a limited group of male users (and a more limited number of female users) keen to employ it in a variety of contexts as a projection of authority, knowledge and resistance.

12 Athletics, one of the quintessential leisure activities in the Victorian era, as described by Donald Mrozek (1983: 1-27), quickly embraced megaphones as an innovation that would not only aid participating athletes, but also entertain and clarify proceedings for the spectators. The chief caveat here, however, is that megaphones were primarily embraced by sports associated with “high culture”—such as rowing and cycling, rather than by more mainstream activities like football and basketball. This peculiarity can be attributed less to economics—given the affordability of the early megaphone—than to the nature of those particular sports, which depended on the megaphone for logistical and commercial reasons. Rowing, in particular, benefited from the addition of megaphones, which were used by the coxswain to dictate the tempo and pace to the rowers in the boat. The Times reported on June 26, 1897, that Ivy League rowing squads all carried megaphones to enable “shouts of encouragement” to reach the different crews. Four years later, a coxswain from Philadelphia “tied a small megaphone around his head and made himself heard plainly” despite “deafening cheers” during the annual regatta of the National Association of Amateur Oarsmen, held in Toronto.6 Similarly, a University of Pennsylvania rowing coach decided to use a megaphone to instruct his crew from a land-based automobile—likely one hundred or so metres away. The April 2, 1918 edition of the Globe reported that the voice of the coach successfully carried “across the stretch and is easily heard by the aspiring and perspiring oarsmen.”

13 Aside from benefiting athletes, megaphones also catered to the needs of spectators at sporting events and, in the process, enhanced the stature of its user. Announcers often used megaphones to provide an endless stream of enthusiastic commentary for the audience to generate excitement and educate those unfamiliar with the event. The organizer of a professional cycling circuit in mid-1890s-New York regularly bemoaned the slow pace of his races and often rectified these tepid performances by grasping a megaphone and shouting “five dollars to the man that sets the pace!” As the Globe reported on August 6, 1895, this seldom failed “to send somebody galloping to the front [and] the spectators like the idea.” Similarly, another cycling race in Newark featured Fred Burns who, in between the music provided by a big band on site, was given the “opportunity to megaphone to the expectant crowd.”7 In Toronto, several thousand fans attended horseracing speed trials at Woodbine Park on May 6, 1934. As M. J. Rodden (1934)reported for the Globe, spectators were captivated by Tom Bird, who didactically announced through a megaphone the names of the horses appearing on the track and their respective racing times. While it is unlikely most fans could clearly hear Bird given the size of the track, his attempts to engage the crowd speak to the cultural currency of the megaphone as an instructive and theatrical device promoting general notions of rest, relaxation and pleasure. Announcers like Burns and Bird relied on them to cement their own status as popular, successful entertainers deserving of a privileged place in the social hierarchy.

14 In certain circumstances, early megaphones also safeguarded security and societal well-being, a function which rendered both tangible and intangible benefits to its male users. The use of the fire trumpet—an object almost identical in form and function to the early megaphone—in particular illustrated this dynamic. Wielded by the fire chief or fire marshal on duty, fire trumpets fostered communication with firefighters battling blazes outside the range of normal voice travel and effectively coordinated the overall fire response operation. Their absence, at times, lowered the chances of managing and containing the conflagration. In 1901, for instance, Mayhew Bronson, fire chief of the Larchmont Fire Department outside New York City, was called to a fire at a local country club and, having not departed directly from the fire hall, arrived without his fire trumpet. In a telephone call back to the hall, he requested his fire trumpet—along with his fire wagon and uniform—to help manage the effort. Nevertheless, the Times reported on January 6, 1901, that the building was completely destroyed. Aside from its utility, the fire trumpet—like the early megaphone, more generally—possessed cultural significance as a marker of social status. In this sense, it elevated those who not only operated the megaphone, but who were honoured with it as a reward for public service, as in the case of George Davis. After twenty-four years as foreman in the New Rochelle Fire Department, Davis was given a fire trumpet by his family as a Christmas present to symbolize his years of civic involvement according to the December 26, 1895, edition of the Times. Similarly, W. F. Hayes received one for serving thirty years in the New York City Fire Department and for possessing “many admirable and sterling qualities.”8 These instances illustrate the extent to which the early megaphone—here in the form of the early trumpet—was invested with particular cultural and social importance as a public, gendered status symbol.

15 Representing cultural power as it did, the early megaphone was also utilized as an entrepreneurial tool in the burgeoning tourism industry of the Victorian era. Leisure excursions to unfamiliar domestic or foreign cities—especially urban destinations—increased in the late 19th and 20th centuries after travel by railroad became more efficient and affordable. Neil Harris, for example, details the meteoric rise of urban tourism in New York City during this period (1991: 66-82). Most of these tourists were moneyed individuals wishing to enjoy themselves at a distance from the masses inhabiting the city. Consequently, large numbers of travellers utilized automobile tours of the city to explore the sights; the tours were inevitably led by a male guide who almost always carried a megaphone to address groups of twenty or thirty people. In a piece titled “Toronto Through A Megaphone” by Rose Rambler (1912), that appeared in the Globe she positively recounted her experience on one of these tours:

Sybil Sketchley (1908) likewise endorsed the megaphone-directed automobile tours as a source of leisure for rural dwellers wishing to explore Toronto. Reminiscing for the July 6, 1908, issue of the Globe about her satisfaction of her own tour of the city, Sketchley noted that “[D]riving through the park in one of those imposing vehicles … labelled ‘Seeing Toronto’ while the man with the megaphone ….” These are things that will give her pleasant memories “through the year to come,” she reported.

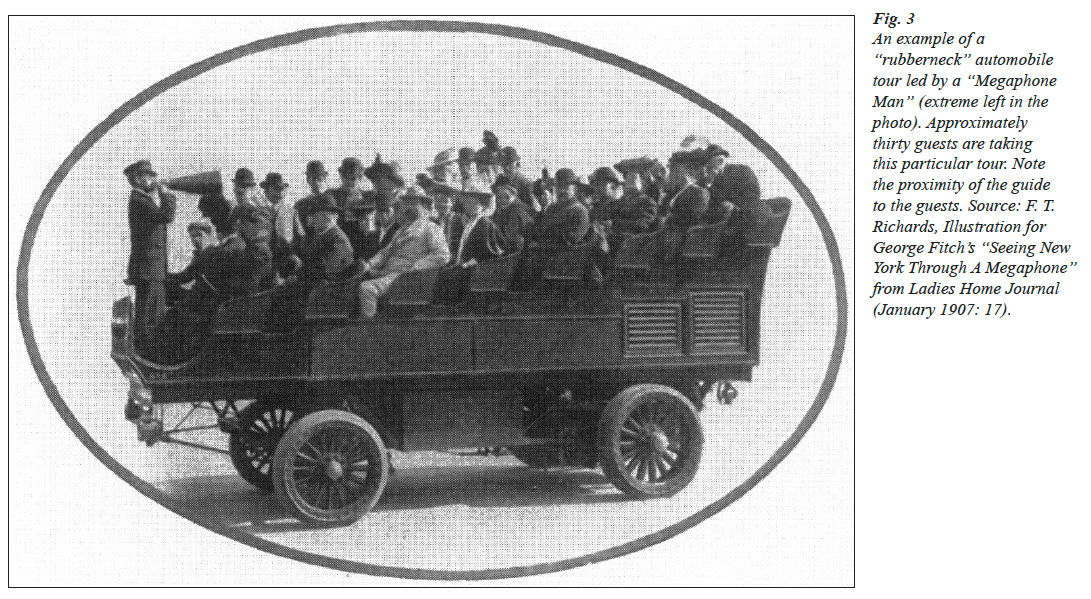

16 In the United States, too, megaphones helped to highlight the sights and sounds of a city for delighted tourists. Canadian teachers visiting New York reportedly enjoyed their “rubberneck” (the colloquial American term for the experience) automobile tour of the Big Apple, and were especially eager to recount the route along the Upper West Side since it was “enlivened by the latest and most approved megaphone jokes about the eccentricities and extravagances of millionaires.”9 In New York, a “Megaphone Man” was always present on these “rubberneck” tours (Fig. 3), which included a visit to Chinatown and cost one to two dollars for the entire experience—a price comparable to an evening at the theatre (Haenni 1999: 501). These tours even inspired imitators, in the form of a “rubberneck wagon” limited exclusively to New Yorkers living on the Lower East Side who wished to see the displays of affluence on the Upper West Side. Despite its localized nature, this “wagon” was nonetheless led by a “professional megaphone man” who was expected to enlighten his travellers about stories of the rich and famous.10

17 Generally speaking, these tours were resoundingly successful by profiting from tourists who chose to spend their leisure time exploring an unfamiliar city. The megaphone, as the primary attraction, was essential to this entire operation since it served to both entertain—by enlivening the mood—and instruct by providing useful historical information or other tidbits, during the trip. The fact that the guide was always a “Megaphone Man” indicates the extent to which the Victorian patriarchal power structure influenced who used the megaphone and for what purpose. While it represented an indispensable element to the Victorian tourism industry in satisfying leisure-seeking tourists and rewarding shrewd entrepreneurs, it was no less significantly an object that signified exclusivity and authority in the hands of its overwhelmingly male users.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 318 As gendered status symbols demonstrating male knowledge and privilege, megaphones were similarly employed as both devices of entertainment and potential deliverers of profit and capital at fairs and exhibitions across North America during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. These sites have been well documented as spaces that not only celebrated modernity and progress, but also promoted conspicuous consumption as a feature of the culture of leisure—a notion first raised by Thorstein Veblen (1918). With respect to the relationship between conspicuous consumption and exhibitions, Keith Walden has argued that participating businesses at the Toronto Industrial Exhibition constructed elaborate displays of goods for sale to symbolize Victorian abundance and generate interest amongst the passing fairgoers (1997: 119-51). Within this intersection of consumption and leisure on the grounds of exhibitions and fairs across North America, megaphones managed to both excite and entice bystanders.

19 First, megaphones entertained fairgoers in attendance at various marquee performances by promoting the spectacle of the occasion. In other words, they helped the crowd appreciate the event as a source of leisure and comfort by fostering a more intimate relationship between performer and audience. A vaudeville comedian duo from New York City, for example, incorporated a megaphone into their act—which involved a bicycle and a sharp decline in elevation—to create a more exciting atmosphere for those in attendance at an exhibition in the city.11 Similarly, W. A. Clarke, an American, presented some scientific experiments involving liquid air to a sizable crowd (exact numbers are difficult to discern) at the Toronto Exhibition in September 1899. As the Globe noted on September 7, 1899,his performance featured a platform placed in front of the crowd and “explanations were made to the audience by means of a megaphone.” Travelling circus performers in New York City also used a megaphone to invite the rapturous audience to personally participate and examine the “freaks”—including a fat lady, short lady and giant, among others—that were part of the performance.12 For performers, the megaphone offered an opportunity not only to entertain, but to affirm and enhance their own social status by demonstrating their value to audiences.

20 If fairgoers were not marvelling at various stunts by intrepid performers, they were likely surrounded across the fair and exhibition grounds by both established businesses and aspiring entrepreneurs hoping to parlay the cultural symbolism of the megaphone into profit from the many potential consumers on site. Megaphones became especially useful in this environment by enabling producers to distinguish themselves and their product offerings—whether food, clothing or some other type of attraction—from the noise of the passing crowd.

21 While it might not have been possible for many fairgoers to fully understand comments filtered through a megaphone, the amplified noise and the authority and confidence radiated by its users constituted enough of an attraction. An Aunt Matilda and her niece fiercely resisted peddlers attempting to sell merchandise at the 1924 Toronto Exhibition, only to be persuaded by a gentleman with a megaphone to walk over to his booth. According to the aunt’s account in the Globe on August 26, 1924, he successfully attracted their attention to corn-on-the cob “with a ‘line’ that would sell a horse trough to a car owner.” Years later, another businessman used a megaphone to entice children and adults to consider a game located at his booth by shouting: “High! Low! High! Low! The time to play is right away.”13 A more bizarre incident occurred in New York City in 1907. Megaphones constituted such a fixture at the boardwalk fair on Coney Island that authorities eventually banned their use and threatened to arrest anyone who defied this order. Suffice to say, the “barkers” (the term given to the peddlers) of Coney Island were unimpressed. In the Times on June 24, 1907, one of the elder “barkers” vehemently criticized the ban by exclaiming, “Cut out the megaphones? Impossible! What would Coney be without megaphones? How are you going to get a crowd to come in and see ‘the boy with the tomato head’ and the rest of the wonders if you don’t talk to them?” The barkers’ vehement resistance to the ban is telling in illustrating how much they—and other men—relied on the megaphone to affirm their own social standing within Victorian society. In other words, it shows the extent to which megaphones had accumulated extensive cultural capital in the Victorian era as gendered communication devices that conferred authority and authenticity (however fleeting) on its predominantly male users.

22 As an object that effectively transcended the boundaries of normal human socialization, the early megaphone came to symbolize a mode of communication primarily associated with leisure and pleasure in North American society, and was accordingly utilized by ambitious entrepreneurs to instruct, entertain and entice during the Victorian era. In 1935, however, the Toronto Exhibition experienced a technological sea change of sorts following the introduction of transistorized microphones with amplified electronic speakers.14 Regular megaphone users like businesses and other entrepreneurs quickly switched to the technologically superior microphone to market their goods, services and attractions. As noted in the Globe on August 15, 1935, the superfluous megaphone suddenly disappeared from the Exhibition and never returned.15 A similar development occurred in the New York travel industry as “rubberneck” tours swiftly replaced megaphones with a public address system for the benefit of their customers.16 While Edison’s original megaphone prototype remained in use in other contexts, these developments presaged the need for a new model which could effectively compete with the microphone and other recent examples of technological progress. The eventual introduction of a transistorized megaphone resolved this dilemma, enabling it to find a new niche as a practical, massmarketed and ubiquitous communication device imbued with enormous cultural relevance in the period following the Second World War.

23 During the war, a patent was granted to Albert Warmbier of Breslau, Germany for an “electroacoustic megaphone” in 1940. As noted in the Times on October 20, 1940, this megaphone included a “built-in microphone, amplifier and loudspeaker, which can be handled like an ordinary megaphone but into which the speaker not yell to make himself heard over wide areas.” Moreover, the design eschewed wires or cables to help power the megaphone, relying instead on “tiny dry cells” located inside the built-in microphone. The microphone, in turn, was mounted with the loudspeaker “in the small end of the megaphone with the amplifier and batteries between the two.” According to the Times on October 20, 1940, the patent noted that this new, electrified megaphone was expected to be used in the military for such purposes as “issuing commands to troops and giving instructions to airplanes for taking off and landing.” While incremental revisions over the next few decades would continue to make Warmbier’s model even more powerful and user-friendly, this patent constituted the dawn of a new era for the megaphone; its communication capabilities were now transistorized and hence greatly enhanced by significant changes in design. These serious design modifications, coupled with growing political and social discord, also influenced who used these objects to communicate and for what purpose. Consequently, in the postwar period the megaphone was transformed from an identifier of male privilege and success to a politicized and democratized cultural symbol as a more expansive, diverse group of users broadened the ways in which it was utilized as a communication medium in North America.

24 Warmbier’s intention that his new “electroacoustic megaphone” be incorporated within military circles for communication purposes was realized before the war concluded nearly five years later. The transistorized megaphone, with improved communication capabilities, constituted the ideal object for commanding soldiers stretched across a wide swath of land several hundred metres apart. For example, according to the Globe for August 9, 1941, a megaphone was used by a gun position officer in the Royal Canadian Artillery to issue orders to his fellow “gunners.” That same newspaper similarly noted on December 15, 1942, that Canadian troops practicing landing exercises were supervised by Major Dave Stewart of Charlottetown, who “shouted orders through a megaphone from the bow of a boat.” The United States Navy also made use of megaphones in likewise fashion and, following the war, found itself trying to reduce its inventory by marketing the surplus to the public. Advertised at $49.50 U.S. ($466.02 in 2011 dollars) in the Times on April 25, 1948, by Leon A. Familant Industries at the Norfolk Army Base in Virginia, as discounted “portable light weight public address sets,” these megaphones weighed approximately four and a half pounds and were “slightly used but in perfect condition.” As an added feature, it was noted that the megaphones were activated by a trigger located on the handle: “Press trigger, and set is in instant operation.”

25 Notwithstanding the cost of this “discounted” megaphone, post-war prices—as in the Victorian era—were generally inexpensive. Many subsequent advertisements promoting the transistorized megaphone mentioned the wartime connection with the Navy, but also acknowledged and emphasized its potential versatility as a useful mode of communication in a variety of other contexts. This surge in advertising reflected broader economic developments as advertisements for various commodities became increasingly common in the postwar epoch in conjunction with the growing commercialization of North American society. Cynthia Lee Henthorn (2006) and Matthew McAllister (1996) both hold advertising responsible for creating a consumer culture built on satisfying escalating wants and needs through the purchase of mass-produced goods. The megaphone could not escape this consumer craze and became increasingly marketed by numerous sellers as a convenient and inexpensive communication device.

26 In the Times on April 16, 1961, an advertisement for Goldsmith Brothers in New York heralded the availability of a Fanon Portable Megaphone for $39.95 U.S. ($303.15 in 2011 dollars) as an ideal object for any environment that required clear, unhindered communication, including athletics, camping and fire services. Madison House in New York City advertised a lighter version at a drastically reduced price of $13.99 U.S. ($91.21 in 2011 dollars) in the Times of March 10, 1968. The company stressed the practicality of this megaphone, which weighed only two and a half pounds, declaring it to be capable of communicating effectively within a range of two thousand feet. Moreover, it noted the feature of volume control as an additional incentive for users wishing to manipulate the resulting amplified sound. A third advertisement—appearing in the Times on June 24, 1972—illustrates a further decline in both cost and weight. According to the ad, Westport World Art and Gift Shop in Westport, Connecticut, offered a lightweight, two pound transistorized megaphone with volume control for $12.95 ($70.29 in 2011). It was said to be impervious to rust, corrosion and salt water, which likely indicates it was made of plastic, a more durable material. This megaphone was also pitched as a versatile communication device with more than half a dozen possible practical uses listed in the advertisement.

27 The proliferation of advertisements involving megaphones indicates it was not immune to the rampant consumerism of the postwar period. Rather, the transistorized megaphone was deeply embedded as a marketable commodity as its producers sought to present increasingly inexpensive, lighter and more effective models to the consuming public. More zealously than in the Victorian era, the modernized model was promoted as an efficient, affordable and practical social device which could be utilized by a multitude of users ranging from construction workers to lifeguards.

28 While the historical record is unclear as to whether transistorized megaphones actually became fixtures at sites such as swimming pools, construction yards or business meetings, it does reveal that other target groups embraced the idea of using a technologically enhanced megaphone. More specifically, state institutions such as police, fire services and other governmental organizations and businesses saw this new model as an object that could operate effectively within the public sphere of civil society by promoting safety and policing law and order. As Whitaker and Marcuse (1994) have noted, the postwar period in North America constituted not only a consumerist paradise but also an age of insecurity which stemmed from the tragedies of the Second World War and the subsequent ideological tensions of the Cold War. For these reasons, safety and law and order became especially important for a wary populace seeking a sense of security on a daily basis. Transistorized megaphones, then, were utilized in a Foucauldian17 sense to promote safety and stability because of their impressive communication capabilities that engendered productive discussion across significant distances (Foucault 1997: 239-63). In Toronto, for example, Fire Chief George Sinclair used a transistorized megaphone for the first time in 1946 to instruct firefighters battling a two-alarm fire in the hope of reducing chances of miscommunication. As the Globe reported on July 19, 1946, the megaphone had been “delivered last night and the Chief carried it to the fire for a trial. By using this latest firefighting innovation, he was able to direct operations by men who were battling flames high above the buildings, where he could not have been heard by ordinary megaphones.” In this sense, the modern megaphone, like its Victorian counterpart, remained associated with longstanding masculinized notions of power and authority as wielding the object automatically conferred a certain social status upon its user.

29 Drawing on these correlations with authority, electronic megaphones were also highlighted as potential lifesavers by the American aviation industry in a sweeping proposal to introduce new safety regulations in passenger cabins in the early 1960s. The proposed regulations by the Federal Aviation Agency stipulated that each plane would be equipped with two transistorized megaphones placed at opposite ends of the fuselage and used during any situation involving an evacuation of the plane.18 Hotels also carried megaphones to warn guests of emergencies, although such directives occasionally went unheeded. A notable example was a hotel fire in Jacksonville, Florida, that killed nearly thirty people as reported by Claude Sitton (1963) for the Times. In that incident, transistorized megaphones were used by hotel officials to caution guests to remain in their rooms until firemen could reach them; many chose to disregard these instructions and perished while trying to escape. The mayor, fire chief and hotel owner all subsequently contended that the fire would have caused almost no fatalities had orders been followed.

30 For police, transistorized megaphones represented not only a lifesaving device, but also a means to enforce law and order in a community and to project an image of hegemony and social control. Police in Toronto, for example, periodically utilized megaphones in their squad cars to deter dangerous driving on provincial highways and city streets. In 1960, a Toronto policeman employed a megaphone to order a speeding driver to the side of the road.19 In other potentially dangerous situations, and in their capacity as protectors of community well-being, the police used megaphones to peacefully resolve activity that threatened people and communities. Transistorized megaphones were especially helpful in fostering negotiations from a distance with suspected criminals. The amplified sound produced by these megaphones could travel between or through buildings and hence helped resolve hostage negotiations by enabling clear communication over significant distances. This proved successful during a New York bank robbery gone awry. As McFadden (1975) wrote in the Times ten hostages were taken and eventually freed after eight hours of negotiations between a megaphone-wielding policeman on the street and the gunman inside the bank.

31 In like manner, transistorized megaphones enabled police to address and disperse social protests of varying sizes. Writing in the Globe, Stan Oziewicz (1978) described how in Hamilton, Ontario, a policeman used a megaphone to request that striking workers at the Fleck Manufacturing Company allow non-striking workers to cross the picket line and repeated his request twice more before riot police entered the crowd. The decision by police to use megaphones to secure and stabilize heated situations both confirmed its utility as a communication instrument for enforcing law and order and enshrined it with political symbolism as a protector of the status quo. In this sense, representatives of the state affirmed Victorian society’s appropriation of the megaphone as a hegemonic instrument of order and control.

32 However, the same protestors facing megaphone-wielding police officers often carried megaphones of their own. Generally speaking, the growth of societal disenchantment and radicalism and subsequent rise of social movements in the 1960s and 1970s in North America has been exhaustively documented by scholars. For example, in his sprawling account of the 1960s in Canada, Bryan Palmer (2009) argues that the decade precipitated a Canadian national identity crisis, while Doug Owram (1996: 159-247) delves into the counterculture and general youth radicalism in his study of the baby boom generation in Canada. Similar themes of disillusionment and anger have been highlighted in works devoted to the United States (Braunstein and Doyle 2002; Stephens 1998: 1-47). Many of these movements—driven by a desire for political, social, economic or cultural change that would redistribute power and influence more equitably—often embraced megaphones as their communication weapon of choice to express frustration with the status quo. For these movements, a transistorized megaphone constituted an ideal device since it was relatively inexpensive, extremely mobile and, with its amplified capabilities, largely effective at addressing large crowds numbering in the hundreds and thousands. In the hands of these protestors driven by the desire for societal reform, it came to symbolize a new vision of power associated with liberation and equity.

33 Transistorized megaphones were occasionally employed by protestors as an outlet for their grievances even before the 1960s and 1970s. In 1948, striking workers at the Rogers Majestic plant in Toronto used them to express their demands for a fair settlement and to advertise their subsequent arrest by police.20 This early incident aside, megaphones were largely conceived as cultural instruments of protest and used by resistance movements during the subsequent decades. Citizens in a New York neighbourhood, for example, brandished megaphones as part of their opposition to increased road congestion caused by a highway construction detour according to Edward Burks (1974) in an article for the Times.

34 The decision by protest groups to appropriate megaphones for their own purposes had wider, far-reaching repercussions related to notions of gender and race and the identities of megaphone users. While men within these movements used megaphones, women and African Americans also employed them. As advocates of social change and, in conjunction with challenging structural gender and racial inequalities reflective of a white, patriarchal power structure, these two groups capitalized on the enhanced communication capabilities of the transistorized model to voice their demands and enhance their public presence—much as white women had done decades earlier in their efforts to win the vote. A megaphone, for example, accompanied Wilma Soss, a septuagenarian and President of the Federation of Women Shareholders in American Business, to a United States Steel Corporation shareholder meeting in 1958. Soss used a megaphone to introduce two failed resolutions and express support for a former employee of the corporation. Her efforts were ultimately unsuccessful but “no one could ignore the woman whose voice was magnified by an electronic megaphone” wrote Wiskari (1958) for the Times.

35 Many younger women also used megaphones as a sign of protest against the established order, often in association with the burgeoning feminist movement. In 1970, the Toronto Women’s Caucus held a rally at city hall to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the successful end to the female suffrage movement. Several women spoke through megaphones to a crowd “packed 15 and 20 deep” and outlined their hope for continued change and the need to initiate a dialogue with the wider public.21

36 Similarly, African Americans in the civil rights movement relied on the megaphone as an instrument of non-violent dissent in advocating an end to the Jim Crow laws in the United States. In Springfield, Massachusetts, protestors involved in a 1965 march brandished an electronic megaphone to vocalize their grievances and encourage bystanders to join in, noted John Fenton (1965) in a Times article. Megaphones also made an appearance at a rally in New York one year earlier, where two hundred African Americans protested the shooting of a teenager by an off-duty police officer. With megaphone in hand, Chris Sprowal, Chairman of the Downtown Chapter of the Congress for Racial Equality, informed the growing number of demonstrators that “people around here just want you to get into trouble so they can point and say, ‘See, I told you so’. But we’re going to fool them, and we’re going to show them that we’ve had some training,” reported Theodore Jones (1964) for the Times. For African American activists like Sprowal, then, the megaphone represented a medium of instruction and, no less significantly, encouragement to continue the battle against racial discrimination.

37 The prominent role of the megaphone in the protest movements challenging racial and gender inequalities in both Canada and the United States served to reconceptualize its cultural meaning in the postwar era. While the users and uses of the transistorized megaphone were not entirely divorced from the early model of the Victorian era, notably with respect to protection of security and order, significant shifts were apparent. In conjunction with the desire for societal change prevalent during the 1960s and 1970s, the transistorized megaphone evolved into a more inclusive, politicized communication device symbolizing widespread disillusionment with the status quo. An increasingly diverse group of users employed heavily marketed, inexpensive, amplified megaphones to demonstrate their right to free speech as voices of dissent during an extremely turbulent epoch. In being refashioned as a more democratized cultural instrument by its diverse users, the transistorized megaphone gradually became associated with notions of liberation and equality in North American society during the postwar period.

38 It is therefore possible to discern a correlation between design modifications and shifts in users, use and cultural symbolism when considering the case of the megaphone between the late 19th and late 20th centuries. The early megaphone, originally introduced in the late 1870s, was relatively simple in design and function and naturally hindered in its capacity to disseminate messages across large distances. Notwithstanding these natural limitations, it functioned as a semiotic symbol of, for the most part, masculine power within the culture of leisure and patriarchy that defined the Victorian era. Accordingly, it conferred social prestige and authority on its primarily male users who employed it as an instrument of knowledge for entertainment and entrepreneurial purposes.

39 The early megaphone, however, was replaced by a modern, electronic model designed and introduced during the Second World War. As a newly amplified device, the transistorized megaphone was markedly more powerful than its predecessor and facilitated clearer communication over larger distances. As a result of design improvements and in conjunction with broader social developments, transistorized megaphones were embraced by new users and imbued with cultural meanings divorced from those of the early megaphones in the Victorian era. Social actors encompassing both the established order and the burgeoning counterculture embraced these powerful megaphones in the postwar era and used them as political and democratic instruments of communication to both protect and contest the status quo. In particular, the latter group of users, including women and African Americans, appropriated transistorized megaphones to further their quest for social change and, in the process, ascribed it with new cultural meanings synonymous with inclusivity, liberation and reform rather than masculine power and knowledge.

40 Of course, these conclusions are not meant to suggest that all of the uses associated with the Victorian era completely disappeared by the late 20th century, only that dynamic shifts in design and broader political and social developments in the mid 20th century precipitated dramatic changes in the identity of users, use and cultural symbolism of megaphones as communication devices.22 This caveat, moreover, can be extended to contemporary society in that it might be possible to discern patterns of current use and meaning derived from both, or neither, of the Victorian and postwar eras. For instance, the “Occupy” movement that originated in New York in the autumn of 2011and quickly swept much of North America might constitute a revealing case study. Yet the results of such an examination will have to be the subject of another study concerning the cultural value of the megaphone.