Exhibit Reviews / Comptes rendus d'expositions

Karsh: Image Maker/Créateur d’images

Ioana TeodorescuVenue: Canada Science and Technology Museum/Musée des sciences et de la technologie du Canada

Exhibit team: Bryan Dewalt, Melissa Rombout, Carole Noël, Carolyn Cook, Annie Jacques, Elizabeth Todd-Doyle and Lupien Matteau Inc

Duration: June 12 to September 13, 2009

Exhibition website: http://www.festivalkarsh.ca/en/exhibition.php/

www.festivalkarsh.ca/fr/index.php

1 During the summer of 2009, Ottawa, Canada’s capital city and adopted home of Yousuf Karsh, was alive with events that marked the one-hundredth anniversary of the renowned photographer’s birth (December 23, 1908). Two years of dialogue between the Canada Science and Technology Museum (CSTM) and Library and Archives Canada’s Portrait Gallery (PGC) resulted in Festival Karsh. The festival included educational programs hosted by museums, art venues and buildings where the artist lived and worked, an online photo sharing group called My Karsh, a website featuring his work and a printed guide of the Karsh trail.1 Combining the two collections and two perspectives of the partners to reveal a coherent and fresh image of the Karsh approach to photography, Festival Karsh also included a major exhibition—Karsh: Image Maker/ Créateur d’images —held at the Canada Science Technology Museum during the summer of 2009.

2 Widely recognized as Canada’s leading portrait photographer, Yousuf Karsh was an Armenian immigrant who settled in Ottawa; hence the location for the anniversary series of events. His prolific legacy in portraiture forms a visual encyclopaedia of 20th-century personalities—Winston Churchill, the British royal family, Glenn Gould, Marshall McLuhan, Georgia O’Keefe, Audrey Hepburn, Pablo Cassals, George Bernard Shaw, Ernest Hemingway and Albert Einstein, among them. Over the years, Karsh’s photographs were repeatedly exhibited in shows around the world. Before it closes in 2012, the exhibition will travel throughout Canada and the world.

3 Yousuf Karsh believed that a photographic portrait captured the essence of an individual in an “elusive moment of truth” (Karsh 1962: 95). He understood this truth as all-encompassing, wrapping “the mind and soul and spirit [in the] eyes, hands and attitude” of a person (ibid.). His photographic sessions were veritable consultations that were elaborately prepared. “Before any session with an important client, Karsh’s first order of business was to research as many facts as possible about the sitter” (Travis 2009: 7). No matter who he was making a portrait of “his primary goal at the beginning of a session was to engage his subject in a cordial and personal way, putting him or her at ease as he determined the number of lights and their exact positions” (ibid.). He was a wonderful conversationalist who would “listen and respond while concentrating on the sitter’s facial expressions...” (ibid.). His approach to a photographic session was applied to celebrities and non-celebrities alike. Karsh took pride in the fact that his portraits were images that encapsulated the historical dimension of individuals.

4 The objective of the exhibit team was to develop an exhibition that not only displayed the legendary portraiture of Yousuf Karsh, but one that provided an analysis of the Karsh techniques, that was interactive and that enabled the visitor to “consider the stories that he told about his subjects and himself.”2 A thoughtful blend of portraiture from the Portrait Gallery of Canada, archival holdings from Library and Archives Canada and artifacts from CSTM’s Karsh of Ottawa Collection helped the team achieve their objective.

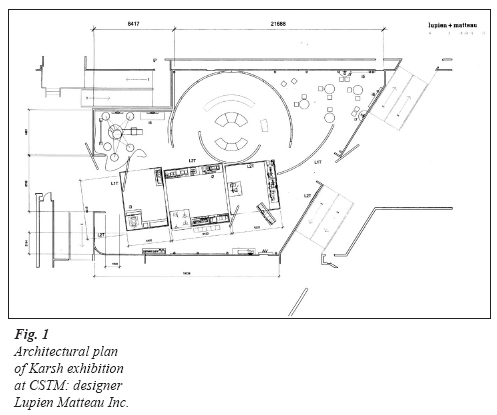

5 The space dedicated to the exhibition at CSTM resembles a trapezoid (Fig. 1), where the artifacts are organized in six different zones. Two entrances accommodate the flow of visitors from different parts of the museum. The “Becoming Karsh” gallery connects the two entrances. Becoming Karsh opens laterally into a succession of three parallelepiped spaces forming an area called “In the Studio.” Here, a corner area representing a studio invites visitors, children as well as adults, to a hands-on exploration of the working space of a professional photographer. This section also functions as a respite area before entering the impressive pantheon where original portraits of celebrities are displayed. The sharp angle of the floor plan has become a memorabilia zone where round tables serve as display space in what is otherwise a rest-and-play area.

Fig. 1 Architectural plan of Karsh exhibition at CSTM: designer Lupien Matteau Inc.

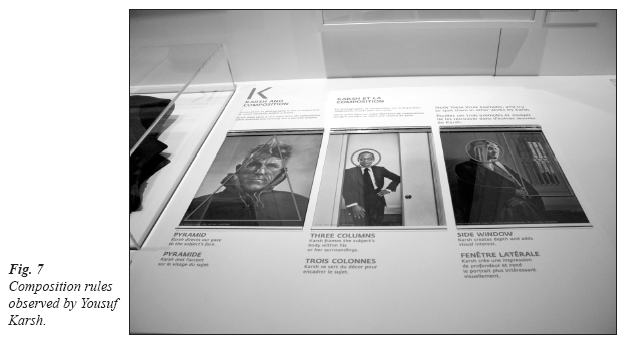

Display large image of Figure 1

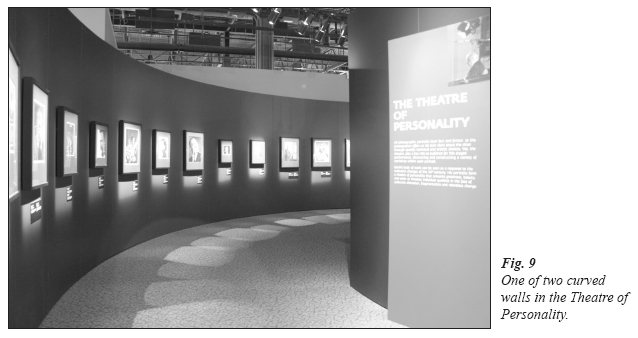

Display large image of Figure 2

6 Despite their distinctiveness in function, the six areas appear as one multi-layered structure. The bold colour scheme chosen by the architectural designers Lupien Matteau Inc of Montreal contribute to the sense of one space. Bright red is the predominant colour. Black and white backgrounds are intertwined with coloured panels throughout; light blue discreetly identifies the two exploration zones on each side of “The Theatre of Personality”; and from within the rotunda, visitors are able to catch glimpses of red through a clever placement of the exhibition walls. Glass display cases and the empty vertical spaces that remain enhance the idea of image making in that they offer indirect views to parts of the exhibition that visitors may have already seen, but are being invited back to explore further. This strategy enables the visitor to absorb small amounts of information at a time so as to grasp the message of the exhibition.

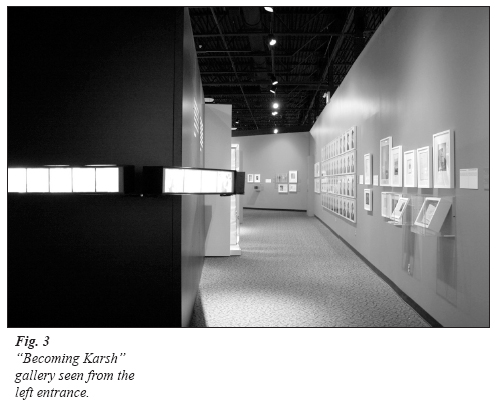

7 Given that Karsh: Image Maker/Créateur d’images is designed to travel, the modular partitions are easily disassembled for installation in other locations. The double-access to the exhibition posed a challenge to curators and designers at the CSTM location, in that the entrance had to be done in duplicate. Two red panels with the K-letter incision indicating the entrances had to be created (Fig. 2). At both entrances, identical bands of slide-like photographs lead the way into the Becoming Karsh gallery. These snap-shots of Karsh at work or at leisure introduce the photographer’s own image to audiences who may or may not know him by sight. Between the two entrances, this gallery acts as a historical esplanade of Karsh’s journey (Fig. 3). Some of his early photographs complement letters exchanged with companies such as the Ottawa Little Theatre where Karsh came to understand the dramatic use of lighting—the defining element in his portraiture. Brushes that once belonged to photographer John Garo, under whom Karsh apprenticed, make the connection to Karsh’s early years spent in his master’s Boston studio, honing the technical and social skills essential to photograph prominent people. A small case holds a replica of Karsh’s first Brownie camera which was a gift from his uncle and teacher, Sherbrooke photographer George Nakash.

8 All of this would have made for an interesting, albeit, common display were it not for a central panel where Arnaud Maggs’s forty-eight portraits of Karsh present a surprisingly different take on portrait photography. Initially, the panel appears out of place, but as one looks back on the show, this piece paradoxically embodies the very essence of this image-making exhibition. Karsh’s slightly different stances act as a magnetic board that draws the visitor inside, only to funnel them deeper into the various meanings the exhibition subtly unfolds.

9 Before turning 180 degrees into the In the Studio gallery, a short video—part of an educational series for children produced by CBC in the 1950s— shows Karsh explaining his first professional steps to an audience which was likely similar to that envisaged for this present exhibition. Co-curator Bryan Dewalt clarifies the exhibit team’s decision to show the video in this section.3 He says it is essential that visitors understand Karsh from the perspective of his having been a refugee from the Middle East, whose dark skin and strong accent were out of keeping with the place he chose to reside; a predominantly white Anglophone Ottawa between two world wars. In his efforts to continually present himself as a true artist, not merely a photographer, one sees an element of self-confidence and self-respect in Karsh; yet, at the same time, this is underlined by an ever-present insecurity that may explain his ambition as a desire for acceptance. Being recognized by the most powerful and the most prestigious was a means to convince Canada, and the world, of his belief that artistic achievement was that part of human nature that transcends boundaries of geography, race, language and class.

10 At the core of the exhibition lie two distinct, yet complementary, spaces—each showcasing artifacts from the collections of the two partners. Library and Archives Canada’s Portrait Gallery program supplies the artifacts for The Theatre of Personality, the portraiture piece of the exhibition. Artifacts from the Canada Science and Technology Museum contribute to In the Studio, the technology aspect of the exhibition. It is fitting that Karsh’s most famous portrait—that of Winston Churchill (Fig. 4)—guards the entrance to this section.

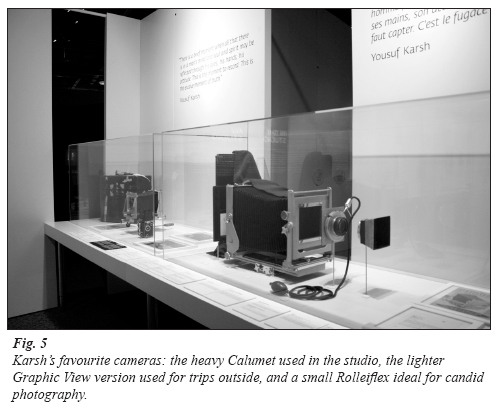

11 Artifacts displayed in the In the Studio gallery provide the visitor with a glimpse of what went into the creation of a Karsh portrait. Here items from the CSTM’s Karsh of Ottawa Collection—cameras, lights, darkroom-related equipment and retouching tools are the focus. The two 8 x 10 (20 x 25 cm) Calumet cameras used by Karsh in his Ottawa and New York studios face each other; one of them is disassembled to expose the working parts to visitors (Fig. 5). Clear and concise explanations accompany the technical objects here, some of which include Karsh’s other favourite cameras: the Graphic View and the Rolleiflex. We learn that the Graphic View camera was used for trips outside the studio because it is small and lightweight, while offering the same swing and tilt control as the Calumet. The Graphic View however, produced negatives of only one-quarter the size of what could be done with the bigger Calumet. The Rolleiflex camera dates from the 1950s and because of its compact size it was used for overseas travel.

Fig. 3 “Becoming Karsh” gallery seen from the left entrance.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 4

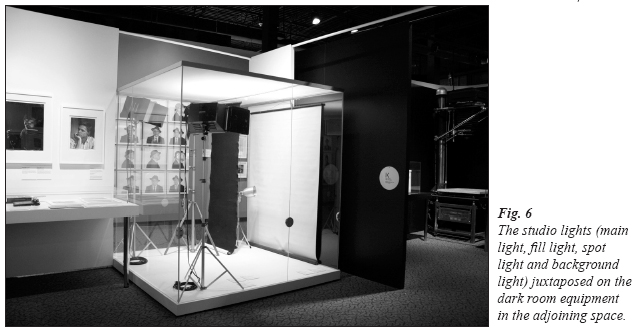

12 Stored conveniently out of the way, but still very much part of the studio, the sitting lights are clustered under a glass corner case allowing a glimpse back into the gallery. Although labelled correctly, an additional explanation might have helped the inexperienced visitor better understand how the lights were used in the actual configuration of the studio (Fig. 6). Nonetheless, juxtaposing the lights on the dark room equipment leaves a metaphorical imprint of the practical story of how pictures are created by carefully balancing light and darkness.

13 In the world of photography, the value of good equipment cannot be underestimated. Equally important, however, is a photographer’s knowledge of how to use that equipment. On parallel walls to the tools and implements, we learn about the various compositional principles Karsh employed (Fig. 7). Visitors are challenged to discover what rules guided the creation of a portrait. Fortunately, the nearby immersive studio brings in a welcome change of pace by allowing a hands-on experience for visitors of all ages. Just in time for restless toddlers, as well as for the serious visitor, this is the place where everybody has an opportunity to apply what has been learned thus far. Secured to a mobile track, a mock Calumet box hiding a digital camera shows an upside-down black-and-white view of a sitter bold enough to have her/his picture taken (Fig. 8). The “photographer” or an “assistant” may adjust the studio lights, while the sitter experiments with costumes and accessories and body positions, working as a team to obtain different results each time. Once a photo is taken, it can be emailed promptly to the sitter’s personal inbox from a touch-screen in the same area. Ironically, this hands-on part of the exhibit proved so successful that the equipment broke down on several occasions—calling into question one’s faith in modern equipment in a technology museum. It will be prudent if the organizers took steps to avoid that complication for future showings of this travelling exhibition.

Fig. 5 Karsh’s favourite cameras: the heavy Calumet used in the studio, the lighter Graphic View version used for trips outside, and a small Rolleiflex ideal for candid photography.

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 7

14 Then suddenly, as if coming out from a wing, the visitor enters the Theatre of Personality. In this gallery, some of Karsh’s most famous portraits line two curved black walls that face each other (Fig. 9). It is here that the spotlight shines on the artifacts provided by the second partner to this collaborative exhibition—the Portrait Gallery of Canada. In the Theatre of Personality, the carefully studied poses of the many celebrities perfectly match the architecture of the space. Well-placed stage lights add to the display of portraits in this gallery to the degree that famous actors are indistinguishable from non-actors. Politicians, scientists and artists alike stand as characters at attention in a play that spans most of the 20th century in terms of time, action and fame.

15 It is important to be reminded that these photographs are veritable artifacts. With current technology, one tends to think of photographs as being easily reproduced. However, a reproduction is only an approximation of the content of an image; an original print is the result of a complete process undertaken by the photographer. Like the tools he used, the images created by Yousuf Karsh have a physical integrity that requires appropriate and on-going maintenance through conservation, proper framing and climate control. The Theatre of Personality actually forges the last link between the two sets of collections. The exhibition presents the story of a professional practice in which some of the displayed objects were used to create other artifacts in the exhibition: they all carry information that can be interpreted. This is the climax of the exhibition. It is here that the awareness unfolds that in touring the exhibition, one witnesses the behind the scenes activity in the creation of an enchanted tale. Like Karsh, the visitor enters backstage into a world inaccessible to the ordinary spectator. Or, is it really inaccessible? After all, visitors observe the process and experiment with the techniques in the fun studio. Is that enough, however, to ignite a passion within individuals whose lives are often too fast-paced to allow for those introspective moments that may lead to something more?

16 With a fine touch, the exhibition brings the artist into the present by linking the concerns of today’s audiences with those of Karsh and his time through challenging messages found on centrally located panels. The inquisitive are dared to question the present roles of celebrity portraiture by asking, “how can photographic portraits be both documents of specific individuals and mass vehicles supplying an insatiable public with enduring images of idols and the transcendent values for which they stood”?4 Equally, the shift in perception of private and public space comes under scrutiny: “has [the] kind polite understanding [which was once established] between photographer and subject disappeared in the age of paparazzi, webcams and Facebook revelations?” Is a photograph showing one more of the many masks of ourselves, or can it still capture the essence of truth like Karsh believed? Can we still identify today (with) archetypal figures like the “visionary politicians,” the “chivalrous war leaders” and “the benevolent business moguls” of Karsh’s world?

17 These are difficult questions to ask, and more difficult to answer. Because he trusted in their healing effects to promote emotional comfort and well-being, Yousuf Karsh donated some of his work to a number of hospitals. Much like the hospital patient, visitors to Karsh: Image Maker/Créateur d’images are encouraged to reflect on, and perhaps confront, their own anxieties through the hope and catharsis offered by Karsh portraiture. This pantheon and Karsh’s legacy are truly magnificent because they possess a classic touch of truth.

Fig. 8 The immersive studio: a mock Calumet case hides a digital camera; studio lights may be adjusted from the panel to the left.

Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 9

18 Exiting the first wing, the visitor enters the second wing of this part of the exhibit. Entitled My Karsh, the display showcases portraits taken by Karsh of people from the general public who responded to an invitation to upload their personal photographs onto the Festival Karsh website.5 This section is small, but presents a fair selection of photographs that ultimately re-connects the viewer to a world composed primarily of ordinary people. It makes for a perfect ending to the effort of de-constructing the myth of Yousuf Karsh as a magician who captured the essence of his sitter in an unplanned moment in time.

Fig. 10 Foyer-like area viewed towards the entrance/ exit.

Display large image of Figure 10

19 The last section of the exhibition resembles a theatre foyer, but fails to function as such. Surrounded by comfortable cubic stools, a few round white tables display souvenir objects related to Karsh’s works—magazine cuts, commemorative plates or stamps made of portraits like that of Queen Elizabeth II. A wall panel holds magnetic pieces with reproduced cuts from famous photographs. Children appear to enjoy moving around the cut-out eyes, mouths, noses and hair-styles, but the panel itself is awkwardly small relative to the wall it sits on. Overall, this last space has an unfinished look that might be intentional on the part of the curators to encourage visitors to carry Karsh’s story outside the walls of the exhibition. At the same time, however, turning towards the exit one feels drawn back into the maze of panels and artifacts, ready to begin the adventure all over again (Fig. 10).

Postscript

20 Karsh: Image Maker/Créateur d’images ran for twelve weeks in Ottawa during the summer of 2009. It met its educational goals and target audience of families, new Canadians and adults interested in culture and communication technology. As expected, the relevancy of the sections varied with the visitors’ level of interest and age. During my three visits, I noticed considerable interaction among such groups. The space thoroughly addressed image making—indeed, besides conveying Karsh’s story, locations within the exhibition walls not carefully choreographed are hard to find and almost any angle makes for a great picture. After Ottawa, the exhibition will run at the new Art Gallery of Alberta in Edmonton from January 31 to May 30, 2010.

21 What made the Karsh: Image Maker/Créateur d’images exhibition special beyond the anniversary is that it marks a first-time partnership between two Canadian institutions that hold collections that are extensive and different in scope. In skilfully combining technical and artistic artifacts, this exhibition not only opened the door onto Karsh’s sophisticated world, but it also constituted an excellent precedent for similar partnerships between other institutions interested in exploring new dimensions of public history.

22 For the 2010 national competition for Canadian exhibitions, the Canadian Museums Association bestowed the Award for Outstanding Achievement in Exhibitions on Karsh: Image Maker/Créateur d’images. The jury unanimously deemed the exhibition to be of national significance and one that exceeded current standards of practice. This is a well-deserved achievement for the team whose dedication and professionalism turned objects into wonders.

References

Karsh, Yousuf. 1962. In Search of Greatness: Reflections of Yousuf Karsh. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Travis, David. 2009. Introd. to Yousuf Karsh: Regarding Heroes, by Yousuf Karsh. Boston: David R. Godine.

Notes