Articles

The Impact of Restaurant Delivery on Montreal’s Domestic Foodscapes, 1951-2009

Alan NashConcordia University

“Mindful Eating” in a “Domestic Foodscape”

1 The work reported in this paper is an outgrowth of my research on the evolution of restaurants in Montreal. It began initially as speculations about how the changing world of restaurants may have affected the domestic foodscape.

2 Since 1951, Montreal has experienced considerable growth in the number of restaurants that serve the city. The growth has been accompanied by a significant increase in both the number and variety of establishments offering menus of an international flavour. Often called “ethnic restaurants,” the cause of their proliferation has been debated, but it is clear that the opportunity to experience the cuisines of the world in one locale allows for local foodways to be exposed to global influences. Should they find foods or menus from elsewhere more appealing or believe them to offer a healthier alternative to their current diet, Montrealers now enjoy greater variety in their restaurant eating experiences (Nash 2009: 9-16). The extent to which having what one scholar called the “the world on a plate” (Denker 2003) in the city’s restaurants translates into more mindful eating practices, either in the public realm or in the domestic foodscape, remains to be investigated.

3 The relationship between dining in a public restaurant and eating in the privacy of the home might not initially be clear; nor might it be immediately obvious how changes in one of these two spheres would necessarily lead to changes in the other. On further reflection, however, I suggest three main reasons that would lead one to expect some connections between restaurants and the domestic foodscape. First, because many North Americans eat both inside and outside the home at different times during any given week, it would make sense that habits and tastes acquired in a restaurant milieu would influence menus, eating behaviour and even perhaps the interior decor of those individuals’ domestic foodscapes. Certainly, evidence shows that the home environment influences the world of the restaurant. Hurley’s fascinating account of the North American diner after the Second World War, for instance, documents how what was once an essentially male-dominated place to feed workers became (through relocation of establishments, changes in cuisine and interior design) more home-like so as to attract a more middle class clientele, and particularly one that included women and children (Hurley 1997: 1287-93).

4 Second, it could be argued that a reliance on restaurant eating (and its greater availability in urban centres) has been one factor enabling the shrinkage of kitchen space in the design of city housing: trends that are themselves mutually reinforcing since a more restricted domestic environment for eating and cooking itself can act as a further impetus to eating outside the home (Levenstein 2003: 163).

5 Third, it could be suggested that the ever-increasing number of hours spent by many North Americans in the paid labour force has gradually eroded the time available for the preparation and consumption of meals at home and has encouraged a greater reliance on restaurant dining (or the purchase of ready-made meals from outside the home, either as “takeout” or as meals delivered from the restaurant to the home) in the interest of saving time for other weekly activities (Morgan and Goungetas 1986: 94-95).

6 It is inevitable, therefore, to expect connections between the public restaurant setting and the private domestic foodscape. Fortunately, mindful eating not only provides the key to the influences of one on the other at a general level, but also articulates their connection at the specific level of the case study chosen here: that of the delivery of meals from restaurants to the home (or “delivery,” for short).

7 The term mindful eating is used by food psychologist Brian Wansink to describe a set of more conscious and reflective eating behaviours encountered in his research into American eating habits: behaviours that contrast with the alternative that he describes, to use the title of his influential book on the topic, as “mindless eating.” He argues that one of the greatest challenges individuals confront “are the hidden persuaders that lead us to overeat” (Wansink 2007: 10). These persuaders form a list that “is almost as endless as it’s invisible”: “endless” because, as research in his food laboratory has concluded, the average individual makes more than 200 food-related decisions a day; “invisible” because something as simple as the size of the dinner plate, larger-sized food packets or the exotic names used in restaurant menus all have an impact on what is consumed. These hidden cues in what Wansink refers to as an “eating script,” are responded to in unreflective ways that result in consuming food that we neither needed nor were even aware we had eaten (Wansink 2007: 1, 27, 57-60, 98).

8 Hidden persuaders are embedded in our surroundings. Whether part of the restaurant or domestic foodscape, they are likely to be different depending on where we eat. Wansink indicates a direct relationship between television viewing and weight. “It’s a scripted, conditioned ritual—we turn on the TV, we sit down in our favorite [sic] spot, we salivate, and we go get a snack” (103), he writes. He further notes, “And because our stomachs can’t count, the more we focus on what we’re watching, the more we end up forgetting how much we’ve eaten” (ibid.). On average, however, people tend to consume smaller amounts if eating at home: having “the whole family around the table at home,” according to Wansink, provides a “standardized rhythm to one’s dining patterns [that] means fewer cues to overeat” (239). Nevertheless, the fact that the size of both dinner plates and the packages of food ingredients sold in supermarkets has increased over the last fifty years makes it largely impossible for someone eating in the home environment to be fully aware of the amounts they are eating (60-68). More obvious, perhaps, is that by moving from the structured, habitual environment of the domestic foodscape to a restaurant situation, the eater is exposed to a variety of hidden cues for unreflective eating—the apparently harmless basket of bread placed on the table before the meal begins, a range of dishes that are usually larger than those found at home and the possibilities of the “all you can eat” buffet.

9 Hidden cues and eating scripts not only contribute to mindless eating, they are also a primary cause of the obesity crisis affecting North America (Arkowitz and Lilienfeld 2009). The inevitable result of allowing ourselves to daily eat an amount that exceeds our bodies’ physiological needs is that over the years we will slowly but surely add unnecessary weight to our bodies (Trivedi 2009: 32). Most diet regimens do little for that problem in that they do not address the root causes of mindless eating. Diets pay little heed—or none at all—to the environmental persuaders that shape our eating behaviour. In what they refer to as the “ecology of eating,” Rozin et al. (2003: 450, 454) point to a host of environmental factors that inform one’s attitude toward food and that contribute to overeating. As Wansink points out, “[e]veryone—every single one of us—eats how much we eat largely because of what’s around us” (2007:1).

10 This awareness can become a path to change, although perhaps not in the direct way that we might at first expect. In itself, simply trying to be mindful about what we eat is a reflective practice that likely cannot be sustained: sooner or later, such new behaviours will themselves become mindless and thereby lose their efficacy. Rather, what Wansink proposes is that the act of mindful eating be seen as a transitional tool—one that if used strategically can be used to shift the eater from one level of mindless eating to another, hopefully less harmful, level of mindless eating—one in which we have used our knowledge of how the food environment functions to write a new eating script for ourselves. He argues:We can reengineer our personal food environment to help us and our families eat better. We can turn the food in our life from being a temptation or a regret to something we guiltlessly enjoy. We can move from mindless overeating to mindless better eating. (Wansink 2007: 209)Clearly, there are many ways of achieving mindless better eating, but eating in a restaurant would not seem be one of them. Fast-food restaurants are in the business of making money from selling meals; it is not surprising that the well-known question “Do you want fries with that”? and other inducements (Schlosser 2001) might be designed to encourage us to eat more rather than to eat less. The practice of eating “fast” tends to encourage over-eating since—in Wansink’s words—“by the time we start to feel full, we’ve already overeaten” (106). Sadly, perhaps, more traditional types of restaurants are no less problematic. As Wansink observes, the “atmosphere of a restaurant can cause you to overeat if it gets you to stay longer,” because we “linger long enough to consider an unplanned dessert or an extra drink (106). Lastly, the behaviour and expectations of customers themselves, once liberated from the constraints of home, can easily lead to mindless eating. Indeed, nutritionists have noted the connection between meals eaten outside the home and less thoughtful eating habits (Ji, Huet and Dubé 2008: 1). Further, a major survey of British eating habits reports:The dramatic performance of eating out is complicated, as detailed ethnographic scrutiny reveals. Having decided to eat out often results in relaxing disciplinary rules: our respondents reported themselves likely to eat more than normal and to pay less attention to health when away from home. (Warde and Martens 1998: 143)The role of restaurants and eating outside the home is more nuanced than these studies suggest. Restaurant eating can be unhealthy, but it does not always have to be. Thus, for example, at least one comprehensive survey of North Americans eating outside the home concluded that “persons consumed foods in a rational way and that where and when foods were consumed had very little impact on their nutritional status” (Morgan and Goungetas 1986: 123). Moreover, restaurant food—if it can be used as part of the mindful transition from mindless overeating to the more reflective mindless regimen discussed above—is surely to be applauded as an end that justifies the means. Restaurants meals may offer a healthier alternative to eating “junk food” at home when there is little time to prepare a meal. By providing an introduction to new cuisines (such as may be found across a range of ethnic restaurants) restaurant meals may also foster within consumers a greater awareness of what they are eating. As Wansink suggests: “[t]he key is to use fast-food restaurants, buffets and warehouse clubs to help you mindlessly eat better while still saving time and spending less” (237).

11 Similarly, the “eating scripts” of people who dine in restaurants need not always encourage overeating, particularly if some of the characteristics of family dining in the home is adopted in the restaurant setting. For example, in their comparative study of the ecology of eating in France and North America, Rozin (2003: 450) and his co-authors found that food portions in France are smaller than in North America. Consequently, restaurant diners in France eat less than diners in North American restaurants. They also found it is the custom in France to take more time than do North Americans to eat a meal—meaning that despite smaller portions, the French have more food experience while eating less (451). The eating scripts of the French appear to have created, in the words of Rozin et al. “a friendlier environment oriented toward moderation” (454). The adoption of these two eating scripts, even just the latter—lingering over a meal, perhaps in the company of friends with good conversation—may trigger for diners an awareness of satiation before being tempted to eat too much. As Wansink reminds us “ [m]any research studies show that it takes up to 20 minutes for our body and brain to signal satiation...” (46).

12 Therefore, even restaurant dining can provide for mindful eating practices if first, we are more aware of what we are eating and, second, we recast our foodscapes in ways that incorporate enduring change. With respect to the first condition, modern cultural geographers and food studies scholars have pointed to the frisson, that momentary thrill or sense of excitement and pleasure often experienced by diners in restaurants as evidence that this is a transformative type of space that lies at the boundaries of private and public space—a liminal space located between the home as a private space in which domestic activities such as cooking are permitted, and the world of the workplace, where only publicly-sanctioned activities may be pursued and the commodification of food preparation is located (cf. Hurley 1997; Spang 2000; Yasmeen 2006: 25-34). In short, new foods, methods of preparation and eating customs can all be encountered for the first time outside the home in a restaurant setting, offering the stimulus for approaching more mindful eating.

13 In terms of the second criterion, that of enduring change, it is perhaps harder to envisage how restaurant dining might itself promote sustained patterns of “mindless better eating”—especially if that change is seen as one that must primarily occur in the domestic foodscape where the bulk of meals in North America are still prepared and eaten. However, if the “ordering out” of restaurant meals to be consumed at home provides one way in which the frisson of the restaurant can be transferred into a domestic milieu, delivery on a regular basis can also be seen as another way in which people with limited time or cooking skills at their disposal are able to augment their cuisine on a sustained basis, and to do so in a way that promotes continued thoughtful choice—one hallmark of the mindful foodscape. Thus, Wansink argues that even mediocre cooks can easily add variety to the domestic foodscape by “buying different foods” and by “visiting authentic ethnic restaurants”—strategies that can be justified in terms of mindful eating, since “[w]hen a child develops a taste for a wide range of foods, healthy foods can be more easily substituted for less healthy ones” (Wansink 2007: 168).

14 Moving the restaurant world into the domestic setting via the delivery of meals signals another sign of effective and enduring change in eating scripts. To domesticate the consumption of restaurant meals ensures that takeout and delivery of food prepared away from the home are eaten in an environment where eating scripts are more structured and where individuals are likely to eat less (Wansink: 239). It is in such a context that the growth and extent of ordering out or the delivery of restaurant meals assumes its place as a relevant topic of inquiry here.

15 Given what has already been said about its perceived merits, it is perhaps not surprising that on a number of occasions in the past century or so, the value of having meals prepared elsewhere and delivered to the home has been promoted. In the 1870s, for example, a number of British social activists suggested this reform—arguing that because the kitchen remained a site of gender inequality, one remedy was to take meal preparation out of the domestic sphere altogether, and into more public, communal kitchens, from which meals could be distributed as required (Pearson 1988: 57, 85). A somewhat different goal was associated with the “New England Kitchen” established by nutrition reformers Mary Abel and Ellen Richards in Boston in 1890. Aimed at improving the diet of the working class poor while reducing its cost, this public kitchen was designed to teach better eating habits to the poor and to replace inefficient individual kitchens with more economical community kitchens (Levenstein 1980: 370-73). Based on the example of the Volksküchen, or “people’s kitchens” that Abel had seen providing soup for the poor in Berlin, it is interesting to note that the American reformers felt it necessary to adapt the concept before its introduction to Boston.The communitarian aspects of … the Volksküchen were not suited to the “free American,” who liked to be “be free in his selection of food,” wrote Richards; “Home and family life are our strongholds,” she added, and “the food must go to the families and not the people to the food.” The first New England Kitchen, therefore, was to be “takeout.” (Levenstein 1980: 375)By the time of the Progressive Era in the United States, “material feminists” were waging a concerted campaign for centralized, cooperative kitchen arrangements across a broad front that included magazine articles, architectural designs and world fair exhibits. Among this list, as Warren Belasco has recently observed, were some remarkable works of utopian fiction, such as Bradford Peck’s 1900 novel The World A Department Store, in which he foresaw “all food prepared by skilled artisans, on a very large scale, which saves the great waste of each private home running its own special culinary department.” Commenting on this vision, Belasco notes that “you phone a restaurant for a home-delivered meal and get a better dinner,” to use Peck’s words, “at about one half of the expense” (Belasco 2006: 110-11).

16 While it is true that part of the concern with meal delivery during this period was a middle-class fear of the growing shortage of servants (Levenstein 1980), much of this literature had altruistic causes, an altruism that has enabled the communal kitchen itself to survive as an institution to the present day, albeit in slightly different guise. In a number of countries, and since 1954 in the United States, formal welfare schemes generally known as Meals on Wheels have delivered meals to many elderly or infirm people whose incapacity in the kitchen would otherwise prevent them from continuing to live in their homes (Anon. 1965; Carlin 2004, 2: 67-68). Interestingly, this tradition can be found in Montreal, where Santropol Roulant (a meals on wheels program that has operated out of the Santropol restaurant) has not only provided over 350,000 meals to seniors and individuals coping with a loss of autonomy since 1995, but has also created over 275 jobs and internships for young people in the community as it has met those needs (Santropol Roulant 2006).

17 More recently, scholars of food retailing have also drawn attention to the significance of people purchasing meals outside the home by using the concept of “food prepared away from home” (FAFH). This phenomenon, while it includes meals purchased in restaurants, also incorporates the amount of fast foods ordered from a franchise, or hot, prepared convenience meals ready to be taken away from the supermarket’s deli counter. Such innovations are, according to more detailed FAFH statistics, increasingly eroding the market niche once dominated solely by restaurants (Brown 1990: 984, 993-94; Park and Capps 1997: 821-23). In one respect, however, these measures show restaurants have always offered additional alternatives to the preparation of meals at home—the “takeout” beloved of the busy person “on the go” (Song 1997)—or (more interestingly, given this research note’s focus on relocating where we eat) the world of restaurant delivery known as ordering out.

18 Finally, to conclude these introductory comments, it is necessary to situate research on restaurant delivery within the general study of the material culture of food and eating. This is because unlike the built form of restaurants, kitchens or food stores, the manufacture of food containers or the evolution of kitchen appliances, restaurant delivery leaves scant permanent physical trace of its presence (Russell 1984; Parr 1995). This is not to say, however, that restaurant delivery has no impact whatsoever—rather, that its influences upon material culture are, for at least three reasons, less immediately obvious. We have already commented on the influence that its availability has had on the design of apartment kitchens and their reduction in size over time (Levenstein 2003: 163). Second, it should be noted that because the act of delivery is essentially an activity rather than an artifact, to the extent that “studies that deal with artifacts abstractly” address issues of “means of distribution, and so on” that reflect or articulate important aspects of our daily lives, they too can be seen as part of material culture (Prown 1982: 1n).

19 Third, it is necessary to observe that because delivery is primarily documented through the printed ephemera of restaurant flyers, menus and in advertisements in print and electronic media, the records of its existence are, by design, impermanent. Many of us, perhaps, have restaurant delivery menus at home—taped onto refrigerator doors, stacked by the telephone, jammed into kitchen cabinets, kept for reference or forgotten until those locations are purged of outdated ephemera. Nevertheless, the fleeting nature of the majority of the artifacts associated with restaurant delivery does not deny their materiality (however short-lived), their role in material culture, or the potential that lies in their examination. Certainly, those studies that have considered the more limited topic of restaurant menus themselves have indicated their value in examining a variety of research topics. In her cultural history of the restaurant in France, for example, Rebecca Spang (2000) devotes an entire chapter to the manner in which the development of early 19th-century menus allowed the names and descriptions of dishes from all over France to be pinned down together in one place for the first time, and how the early menu, in this way, placed what was almost an atlas of French cuisine into the hands of the Parisian gourmet.

20 Other scholars have used menus to track regional variations in the words used for particular meals across North America and, in particular, how “foreign” cuisines have been described (Teller 1969; Zwicky and Zwicky 1980); how “item positioning” of the images of meals placed on the large, backlit photographic menu board of one large American fast-food chain affects a meal’s popularity (Sobol and Barry 1980); and as a teaching tool to illustrate the nuances of social or cultural difference (Hydak 1978; Wright and Ransom 2005), noting that the use of “everyday taken-for-granted institutions and their artifacts, such as restaurant menus, is an excellent way to introduce students to the role of social class in shaping their lives” (Wright and Ransom 2005: 316).

21 Indeed, as one of the unconsidered aspects of our everyday existence, it could be argued that restaurant delivery itself has been able to make a contribution to our material culture that is no less intriguing than some of those activities that leave more durable evidence.

Research Strategy and Methodology

22 As readers of this journal will appreciate, the study of material culture often requires unorthodox research strategies regarding methodologies for data collection and interpretation. This analysis of changing patterns of restaurant delivery using, as a case study, the city of Montreal over the period 1951-2009 is no exception. For the early part of the period, as with many other phenomenon that were once part of everyday life, ordering out was an activity whose apparent insignificance did not prompt sufficient critical attention to merit a focused reporting of its occurrence—either on the part of customers or restaurant owners themselves. It is therefore difficult to gauge the extent of the activity of ordering out of meals at any particular point in time. This problem is further compounded when we endeavour to consider the present and, thereby, those changes that have occurred through time because, ideally, such a study would require sources that are both consistent through time and space if they are to be at all indicative of trends in meal delivery that have occurred over fifty years in a large urban area.

23 Therefore, to ensure as thorough a coverage as possible, this research has relied upon an analysis of the descriptions occurring in restaurant entries in the classified telephone directories (popularly known as the Yellow Pages) for Montreal over the period 1951-2004, supplemented, wherever possible, by the use of advertisements in trade directories (Fig. 1), newspapers such as The Gazette and the worldwide web.

24 For those unfamiliar with the general use of telephone directories in such types of research, it is important to note here that they are considered a well-tried and reliable source in restaurant studies (Zelinsky 1980); even by the turn of the millennium, alternatives such as the web had made little impact on their dominance as an advertising media (Filler 2002: 170-71; Hoggart, Lees and Davies 2002: 185). Of course, this is not to say that the use of the Yellow Pages is ideal since not every restaurant will have had a phone (especially in the 1950s) and not all that did will have paid to appear in the phone directories. Other problems, including inaccuracies ranging from 10 to 20 per cent of restaurant listings in one case study, have led some scholars to suggest that phone directories should only be used in conjunction with field work (Pillsbury 1987: 327).

25 However, direct observation of this sort is obviously not always possible in historical case studies. A recent study of the growth of Mexican restaurants in Omaha over the ninety-year period from 1910 to 2000 concludes that Yellow Pages data “provide a fairly accurate portrait of the restaurant scene” (Dillon, Burger and Shortridge 2006: 39-40), echoing the endorsement Wilbur Zelinsky made in his classic study of the distribution of “ethnic restaurants” in North America: that, by their very nature, the Yellow Pages “cannot help but be an excellent source” (Zelinsky 1985: 55).

26 Taking heart from conclusions such as these, what can we learn from an analysis of the Yellow Pages about the development of restaurant delivery in Montreal? For the purposes of this research note, let us consider the endpoints of our period: the years 1951 and 2004.

Data and Analysis

27 The data recorded in the 1951 Yellow Pages first show that with only a total of twenty-four restaurants involved in delivery, this was a relatively minor activity (recognizing, of course, the limitations of the data). Second, the types of cuisine (in as much as they can be inferred from the establishments’ names and brief descriptions in the directories) are restricted to only a few main types. Thus, the leading category of those seventeen that could be classified was of the “light lunch” variety (eleven cases, or 46 per cent of the total), of which four served hot dogs, hamburgers or sandwiches, and three were essentially food stores that also provided delivery—a service to customers that typified many small grocery outlets in Montreal during the interwar years (Taschereau 2005: 237).

28 Some of these restaurants also provided a brief description of the type of cuisine they delivered, and from this limited information it can be seen that two delivered chicken or chicken barbecue, one provided “an exclusive Italian cuisine,” and another three restaurants specialized in Chinese dishes—producing a total of only 16.7 per cent of order out restaurants in 1951 that delivered what might be described as “international cuisines.”

29 These data can be compared with equivalent information from fifty years later (summarized in Table 1). Surprisingly, perhaps, the total number of restaurants that offered delivery in 2004 according to the phone directory, a figure of forty-two, was not that much higher in absolute terms than the total number for 1951. In relative terms, however, the increase is an impressive one of 75 per cent over the fifty-year period, but the small numbers involved obviously caution too much value being placed in such a finding.

30 More important perhaps than any evidence of increase in restaurant numbers is the fundamental change in the type of cuisines available by 2004. In that year, only eight restaurants (or 19 per cent of the total) delivered cuisines that could be defined as “non-international” (of which seven served chicken barbecue), while 81 per cent (thirty-four restaurants) provided international choices. Of the latter, the overwhelming majority (fourteen) were made up of pizza delivery businesses, with the remainder comprising a potpourri of world regions: from Italian (with four restaurants), to East Indian (four), Japanese Sushi (four), Thai (two) and (with one each) Nepalese, Lebanese, Greek, Antillean, Chinese and “world cuisine” restaurants. Even if we are reluctant to consider pizza as authentic Italian fare, there is still far more variety in international cuisines available to those who chose restaurant delivery in 2004 than 1951.

Fig. 1 An advertisement that appears on the inside front cover of the 1965 edition of Lovell’s Montreal Street Guide. Courtesy of Jamie Lovell, President.

Display large image of Figure 1

31 Such conclusions are not wholly unexpected, given what we know of Montreal’s overall restaurant scene in the 1950s and its subsequent changes. Thus, the city’s many jazz clubs of the 1940s and 1950s may have fuelled a large demand for outside dining, but according to menus that survive, the majority of restaurants in such clubs provided a selection of steak, chicken and chops; The Club Lido, with its Chinese and Italian specialties, was a notable exception to this picture (Weintraub 1996; Marrelli 2004: 76, 110, 113).

32 Contemporary guidebooks to Montreal reinforce this view. For example, according to the American Tourist Association’s 1955 guide, the city offered diners seeking something other than a chophouse a very limited number of Italian and Chinese restaurants. Establishments such as Rieno’s Curbside Restaurant, which specialized in “chicken Bar-B-Q, turkey dinners, spaghetti, steaks and chops,” can be taken as representative of menus that were available at the time (American Tourist Association 1955: 1-7).

33 Information from the 1951 Yellow Pages suggests that there were a total of 162 restaurants serving international cuisines in Montreal. Of these, 101 (62 per cent) of the restaurants can be classified on the basis of their name (or according to other diagnostics appearing in their telephone description) as European (of which 48, or 29 per cent of the total, were Italian and 39 (24 per cent) were Eastern European). If the twenty-one restaurants classified as Jewish are also added to this figure, the European total approximates 75 per cent of all ethnic restaurants found in Montreal in 1951. With 17 per cent of the remainder, the next major category of ethnic restaurant was Asian, the majority of which were Chinese restaurants (with twenty-two establishments). From today’s perspective, this appears to be a very limited roster, with at best only three or four ethnic cuisines (Italian, Eastern European, Chinese and Jewish) obtainable in any numbers across the city.

34 Newspapers provide another glimpse into the city’s past and, although relatively few restaurants appear to have advertised their services in the pages of The Gazette during the 1950s, the pattern that emerges corroborates the picture provided by our other sources. Thus, the year’s largest listing by far—the 1951 “Christmas Greetings” advertisement placed in The Gazette on December 25, 1951 by the city’s Café and Cabaret Association—recorded a total of twenty-eight restaurants, of which 79 per cent evidently served some type of local or Canadian cuisines, and only six (three Italian, three Chinese) identified their menus as internationally inspired.

35 By 2001, the total number of restaurants in Montreal had increased to more than 5,000 and—perhaps more to the point—was now almost entirely made up of establishments serving a much wider variety of international cuisines. Thus, out of a total of 787 ethnic restaurants recorded in the Yellow Pages in that year, the data show that the European component had declined since 1951 to 50 per cent of the total number. In contrast, the Asian component rose to 32 per cent (252) in 2001. It is also worth noting that a number of smaller restaurant categories also grew over this period and began, as it were, to become noticeable additions to the city’s restaurant scene. For example, fifty-seven Arabic restaurants and twenty-eight East Indian restaurants are recorded and increases in the number from regions such as the Caribbean and South America are also evident. Interestingly, in view of the possible impact of electronic advertising upon traditional print media, these general findings are supported by an analysis conducted in 2007 of RestoMontreal.ca, the leading online guide to restaurants.

Table 1 Total number of restaurants in Montreal 1951-2004

Display large image of Table 1

36 Additional windows into the world of the eating habits of Montrealers in 1951 and in the present day can also be provided by qualitative ethnographic research. While it is obviously easier to examine the population’s current dining behaviour—through direct observation or questionnaire survey, for example—it is also possible to uncover past patterns through interviews conducted with individuals old enough to remember their eating habits fifty years ago. With these aims in mind, an attempt to survey the eating habits of Montrealers in 2009 and the 1950s has been initiated as a university-based class exercise as another part of my ongoing research into restaurant delivery in Montreal, and it is instructive to examine some of the initial findings of the survey here.

37 To consider present habits first, according to their responses to the questionnaire, the great majority of seventy-eight undergraduates participating in the course GEOG 321 (“A World of Food”) taught at Concordia University (2009-2010) reported in September 2009 that they ate in restaurants once or twice a week. With respect to the delivery of meals from restaurants however, only twelve of those seventy-eight people noted they had ordered delivery at least once during the week of observation, and an additional two individuals noted they only ordered delivery “once or twice a month.” Most often, the delivered meal took the form of a pizza, and the stated reason was either one of habit (“we always get delivery on a Thursday evening,” to quote the student), or of necessity. Thus, one student who noted that their family ordered delivery three times during the observation week commented that delivery “occurred when Mom came late from work; no time to cook.”

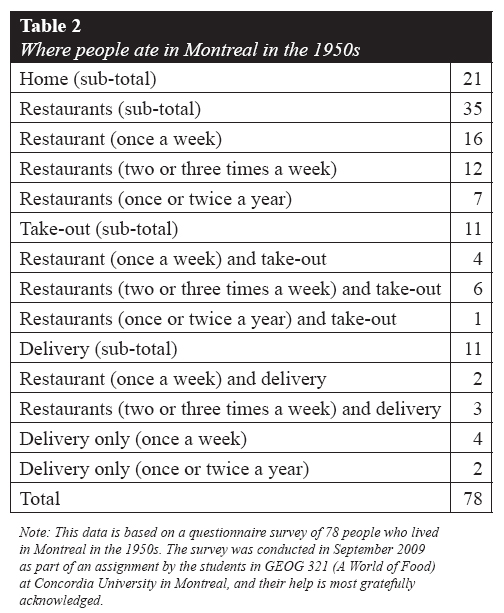

38 How does this experience compare to that of fifty years ago? In order to begin to answer this question, the seventy-eight students participating in the survey each interviewed one person who recalled their own eating behaviour in the 1950s. Those interviewed were often the student’s parent or grandparent, but in cases where the student was newly-arrived in Montreal, a variety of landlords, neighbours and relatives of friends were interviewed instead. The results are interesting for at least three reasons and, because the eating habits of fifty years ago are less easily uncovered than those of the present day, are presented in greater detail in Table 2.

39 The clearest conclusion to emerge from a comparison of these data with today’s experience is that, during the course of a week, more people in the 1950s ate all their meals at home (some even making a habit of dining with friends or relatives once or twice a week—to spread the cost and labour of cooking, according to one of those interviewed). The second feature is the corollary: that relatively fewer people were choosing to eat in restaurants in Montreal fifty years ago. Third, even though restaurant dining was reported by a smaller proportion of the survey population as part of their eating habits in the 1950s (our data suggests a figure of approximately 44 per cent), it is intriguing to note that the proportion of those who elected to have restaurant delivery represented 14 per cent of the total interviewed—a percentage that has not substantially changed for fifty years, since it is almost identical to that of 15 per cent found in the 2009 sample population and reported above.

Conclusions

40 It is evident from our data that between 1951 and 2009, the city of Montreal experienced—as did other cities in North America and around the world—a rise in what researchers have called the “ethnic restaurant” that offered a wide range of dining possibilities. It is also evident that the expansion of restaurant delivery and the wider “internationalization” of options for ordering out were part of those same changes. It was now, for example, far more likely that any meals that were delivered to the home would be sushi rather than hot dogs, curries rather than sandwiches.

41 The primary reasons for such developments have occupied considerable attention in the scholarly literature on this topic and require mention here inasmuch as they also affect the changes described here in terms of restaurant delivery. Regarding restaurants themselves, for example, one view is that the rise of ethnic restaurants is due to a growing postmodern fashion for international cuisine. An alternative explanation attributes the rise to the increasing and more varied immigration patterns into Canadian cities (Turgeon and Pastinelli 2002; Nash 2009). Whatever the significance of these factors, one of the great world fairs, Expo 67, had its own impact on the rise of ethnic restaurants in Montreal. In a lecture she delivered in 2004 on the food culture of Montreal in the 1960s, Rhona Richman Kenneally noted that[t]hose interested in cuisine were able to experience the whole array of international foods at Expo. You could have breakfast in Paris, go to England for a beer and then to Scandinavia for dinner.... Because the environment of Expo was a reflection of architecture and ideals of modernism and was so focused on the progress of humanity in many fields, the idea of eating international foods was conceptualized as a modern practice ... food became a ... vehicle for individuals to feel like they were being modern. (Qtd. in McNally 2004)In such a context, therefore, it is apparent that restaurant delivery—with its obvious associations with transport and thereby the latest approach to food preparation—allows a more modern, and perhaps more fashionable, style of eating to become incorporated into the domestic foodscape. (This observation also suggests that one of the attractions of being able to order meals from the web is less the anonymity of the transaction than the fact that the process itself is part of a trend-setting technology.) There is clearly much more research needed before the exact nature of these relationships can be teased out.

Table 2 Where people ate in Montreal in the 1950s

Display large image of Table 2

42 Leaving general speculations aside, what our data clearly show is that the delivery business had completely changed the relative categories of meals being delivered over the fifty-year period of observation, from the 17 per cent or so of restaurants which offered delivery of “international” cuisine in 1951, to the more than 80 per cent of recorded establishments in 2004 that offered such choices. In other words, by the beginning of the 21st century, it would appear that ordering out and wishing to eat internationally inspired meals have become almost synonymous activities. As Tara Ann Lynn writes in her poem “Free Delivery,” “[t]he cuisine of the world is just a phone call and about twelve dollars away” (Lynn 2003). In a way that it never could fifty years before, the restaurant delivery business is now able, almost literally, to deliver the world into people’s homes.

43 Of course, the world that delivery offers is far more limited in reality than poetry might suggest, providing but a few leading international cuisines as ordering out options. However, the fact that it is ordered for home consumption is crucial to our concerns here and forms the basis for our second, more speculative set of conclusions. In short, while restaurant delivery appears to suffer from many shortcomings, and is often seen as a stop-gap solution by those with insufficient time to prepare a meal, it is nevertheless a solution that can promote more mindful eating because it is an activity that brings meals into the home where they are eaten. By bringing meals from the public sphere into the domestic realm, food can be consumed—often accompanied by small healthy additions such as salad and fruits provided from the family kitchen—at a leisurely pace, in an atmosphere that promotes conversation and interaction with family and perhaps friends and where, as Wansink suggests, cues to overeat are generally fewer (239).

44 That guilty frisson we often experience when ordering out may be part of the friction caused as private and public spheres meet in the same place, but it is in such hybrid spaces that new worlds are crafted, and perhaps new forms of mindful eating are fashioned.

Note

I am extremely grateful to James Lovell (President, Lovell Litho and Publications Inc.) for his kind permission to reproduce here the advertisement for Chez Corneli that originally appeared on the inside cover of the 1965 edition of Lovell’s Montreal Street Guide. I am also grateful to Rhona Richman Kenneally for her encouragement to undertake this work and to an anonymous referee for their constructive comments. This paper has greatly benefited from the considerable skills of Marie MacSween in its copy editing stages: I particularly wish to acknowledge her keen eye for detail and her care in the felicity of expression. Finally, I would like to thank my father-in-law, Gregory Skalkogiannis, whose delivery of wonderful home cooking has encouraged me to move to a more mindful eating.References

American Tourist Association. 1955. 1955 American Travel Guide: Canada. Montreal: American Tourist Association.

Anon. 1965. “Meals on Wheels” Grows. Science News Letter 87 (25): 388.

Arkowitz, Hal and Scott Lilienfeld. 2009. Facts and Fictions in Mental Health: The Effect of Our Surroundings on Body Weight. Scientific American Mind 20:68-69.

Belasco, Warren. 2006. Meals to Come: A History of the Future of Food. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Brown, Douglas M. 1990. The Restaurant and Fast Food: Who’s Winning? Southern Economic Journal 56 (4): 984-95.

Carlin, Joseph. 2004. Meals on Wheels. In The Oxford Encyclopedia of Food and Drink in America, ed. Andrew F. Smith. 2 vols. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Denker, Joel. 2003. The World on a Plate: A Tour Through the History of America’s Ethnic Cuisine. Boulder: Westview.

Dillon, J. S., P. R. Burger and B. G. Shortridge. 2006. The Growth of Mexican Restaurants in Omaha, Nebraska. Journal of Cultural Geography 24 (1): 37-65.

Filler, Daniel M. 2002. Lawyers in the Yellow Pages. Law and Literature 14 (1): 169-96.

Hoggart, Keith, Loretta Lees and Anna Davies. 2002. Researching Human Geography. London: Arnold.

Hurley, Andrew. 1997. From Hash House to Family Restaurant: The Transformation of the Diner and Post-World War II Consumer Culture. The Journal of American History 83 (4): 1282-1308.

Hydak, Michael. 1978. The Menu as Culture Capsule. The Modern Language Journal 62 (3) 111-12.

Ji, Lu, Catherine Huet and Laurette Dubé. 2008. The Emotional and Social Landscape of Home Vs Away-from-Home Meals and Their Influence on Eating Pattern: An Experience Sampling Study with Non-obese Adult Women. Paper presented at the workshop Domestic Foodscapes: Towards Mindful Eating, Concordia University, Montreal.

Levenstein, Harvey. 1980. The New England Kitchen and the Origins of Modern American Eating Habits. American Quarterly 32 (4): 369-86.

———. 2003. Revolution at the Table: The Transformation of the American Diet. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Lynn, Tara Ann. 2003. Free Delivery. English Journal 93 (2): 97.

McNally, Shelagh. 2004. Man and his Stomach: How We Discovered New Dishes. Concordia’s Thursday Report. Montreal: Concordia University. http://ctr.concordia.ca/2004-05/nov_04/02/) (accessed November 4, 2009).

Marrelli, Nancy. 2004. Stepping Out: The Golden Age of Montreal Night Clubs, 1925-1955. Montreal: Véhicule Press.

Morgan, Karen and Basile Goungetas. 1986. Snacking and Eating Away from Home. In What is America Eating? Proceedings of a Symposium, ed. Food and Nutrition Board, Commission on Life Sciences, National Research Council, 91-125. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Nash, Alan E. 2009. From Spaghetti to Sushi: The Evolution of Ethnic Restaurants in Montreal, 1951-2001. Food, Culture and Society 12 (1): 5-24.

Park, John L. and Oral Capps. 1997. Demand for Prepared Meals by U.S. Households. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 79 (3): 814-24.

Parr, Joy. 1995. Shopping for a Good Stove: A Parable about Gender, Design and the Market. In A Diversity of Women: Ontario, 1945-1980, ed. Joy Parr, 75-97. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Pearson, Lynn F. 1988. The Architectural and Social History of Cooperative Living. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Pillsbury, Richard. 1987. From Hamburger Alley to Hedgerose Heights: Toward a Model of Restaurant Location Dynamics. The Professional Geographer 39 (3): 326-44.

Prown, Jules David. 1982. Mind in Matter: An Introduction to Material Culture Theory and Method. Winterthur Portfolio 17 (1):1-19.

Rozin, Paul, Kimberly Kabnick, Erin Pete, Claude Fischler and Christy Shields. 2003. The Ecology of Eating: Smaller Portion Sizes in France than in the United States Help Explain the French Paradox. Psychological Science 14 (5): 450-54.

Russell, Hillary. 1984. “Canadian Ways”: An Introduction to Comparative Studies of Housework, Stoves, and Diet in Great Britain and Canada. Material History Bulletin 19 (Spring): 1-12.

Santropol Roulant. 2006. History. www.santropolroulant.org/2006/E-history.htm (accessed September 9, 2009).

Schlosser, Eric. 2001. Fast Food Nation: The Dark Side of the All American Meal. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Sobol, Marion and Thomas Barry. 1980. Item Positioning for Profits: Menu Boards at Bonanza International. Interfaces 10 (1): 55-60.

Song, Ming. 1997. Children’s Labour in Ethnic Family Businesses: The Case of Chinese Take-Away Business in Britain. Ethnic and Racial Studies 20 (4): 690-716.

Spang, Rebecca. 2000. The Invention of the Restaurant. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Taschereau, Sylvie. 2005. “Behind the Store”: Montreal Shopkeeping Families Between the Wars. In Negotiating Identities in 19th and 20th Century Montreal, ed. Bettina Bradbury and Tamara Myers, 235-58. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press.

Teller, Joan. 1969. The Treatment of Foreign Terms in Chicago Restaurant Menus. American Speech 44 (2): 91-105.

Trivedi, Bijal. 2009. The Calorie Delusion. New Scientist 203 (July 15): 30-33.

Turgeon, Laurier and Madeleine Pastinelli. 2002. “Eat the World”: Postcolonial Encounters in Quebec City’s Ethnic Restaurants. Journal of American Folklore 115 (456): 247-68.

Wansink, Brian. 2007. Mindless Eating: Why We Eat More Than We Think. New York: Bantam.

Warde, Alan and Lydia Martens. 1998. A Sociological Approach to Food Choice: The Case of Eating Out. In The Nation’s Diet: The Social Science of Food Choice, ed. Anne Murcott, 129-46. London: Longman.

Weintraub, William. 1996. City Unique: Montreal Days and Nights in the 1940s and 1950s. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart.

Wright, Wynne and Elizabeth Ransom. 2005. Stratification on the Menu: Using Restaurant Menus to Examine Social Class. Teaching Sociology 33 (3): 310-16.

Yasmeen, Gisèle. 2006. Bangkok’s Foodscape: Public Eating, Gender Relations, and Urban Change. Bangkok: White Lotus.

Zelinsky, Wilbur. 1980. North America’s Vernacular Regions. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 70:1-30.

———. 1985. The Roving Palate: North America’s Ethnic Restaurant Cuisines. Geoforum 16 (1): 51-72.

Zwicky, Anne and Arnold Zwicky. 1980. America’s National Dish: The Style of Restaurant Menus. American Speech 55 (2): 83-92.