Articles

Entertaining Eats:

Children’s “Fun Food” and the Transformation of the Domestic Foodscape

Charlene D. ElliottUniversity of Calgary

Résumé

Cet article se penche sur la signification des produits alimentaires de supermarché ciblant la clientèle des enfants (fun food), en avançant que la valeur symbolique de cette « nourriture ludique » réside dans le fait d’être présentée comme un divertissement, une autonomisation et une expérience pour les enfants. La nourriture ludique crée un espace affirmant les préférences et les goûts exclusifs des enfants en les mettant symboliquement à distance du monde de la nourriture des adultes. Le fait d’examiner ces produits permet de nouveaux aperçus sur : la configuration contemporaine de « l’enfance » ainsi que l’accentuation de la notion de « jeu » ; sa place dans le « paysage alimentaire » domestique moderne. J’avance que le fait d’amener la nourriture ludique dans le paysage alimentaire domestique crée une espace pour les rituels alimentaires (de transgression) propres aux enfants, tandis qu’elle provoque chez eux une manière totalement différente d’avoir conscience de s’alimenter : manger, non pas en étant distrait, mais en tant que distraction en soi. La nourriture ludique incite les enfants à être conscients de leur consommation parce qu’elle leur procure une extension du jeu.Abstract

This article explores the significance of child-targeted supermarket foods (or “fun foods”), arguing that the symbolic value of fun food resides in its promotion as entertainment, empowerment and experience for children. Fun food carves out a space that affirms the unique preferences and tastes of children while establishing their symbolic distance from the world of adult foods. Examining these products provides novel insight to both the contemporary configuration of “childhood” and its versioning of “play” as well as its place in the modern domestic foodscape. I argue that bringing fun food into the domestic foodscape creates a space for children’s own (transgressive) food rituals, while fun food fosters in children a very different kind of mindful eating: eating, not while distracted, but as distraction itself. Fun food encourages children to be mindful of consumption because it promises an extension of play.1 In 1999, marketer James McNeal lamented that “[g]ood kids’ packaging is hard to find. On the A-K scale (adult to kid), the design of most packaging for kids’ products skews toward the A end” (1999: 88). Such packaging fails to serve the “end user” of the child, argued McNeal, and so he devoted an entire chapter of The Kids Market to careful instructions on how to “kidize” packaging.

2 Today, “kidized” packaging is commonplace. With corporations realizing the enormous market potential of child consumers (and child-targeted products), the balance on McNeal’s “A-K scale” is now tipping towards the “K.” This is particularly evident in the world of supermarket packaged foods. Edibles specifically targeted at children have gained prominence; in the grocery store, a vast selection of packaged “fun foods” vie for the attention of both parents and children. Such fun foods deliberately target children through the use of cartoon images, bright package colours and curious product names, flavours and/or colours: fun food packages frequently reference “fun” or play and highlight the food’s entertainment or interactive qualities. Overall, these foods are marketed as eatertainment—they foreground foods’ play factor, artificiality and general distance from ordinary or “adult” food, while resting on the key themes that food is fun and eating is entertainment (Elliott 2008; 2008a). Black Diamond, for example, sells FunCheez in dinosaur, fish, moon and planet shapes. General Mills’ Lucky Charms instructs children to use “your favourite Lucky charm” marshmallows as game pieces for the game printed on the back of the cereal box. Kool-Aid’s Magic Switchin’ Secret crystals promise a secret flavour and also “magically” change colour when mixed.

3 Fun foods provide yet another instance of how childhood is being tapped by the commercial market. Children represent the largest and fastest growing market segment (Kapur 2005: 24), as well as being a powerful “influence” market on parental purchases (McNeal 1999: 12). Given this, it is not surprising that $15 billion is spent annually on marketing to children (Rose 2007: 23). Food marketing is particularly robust, with an estimated $33 billion spent annually on direct advertising (Schor and Ford 2007: 11). While data is not available on the sales of fun foods in Canadian supermarkets, market research indicates that sales of foods specifically aimed at American children (aged 3 to 11) surpassed US$15.1 billion in 2006—an increase of 8.5 per cent from 2005. These sales are projected to reach $27 billion by 2011 (Gates 2006: 39). Such staggering figures make it tempting to focus on fun foods as either a marketing coup (as the marketing or food industry might) or an exploitation of childhood (as would critical scholars and some policy analysts). The intent of this paper, however, is to explore what this new category of consumables suggests about the domestic foodscape. Specifically, I am interested in analyzing the symbolic messages embedded in fun food/food packaging in light of the domestic foodscape. To this end, I ask: What is the significance of these “entertaining eats” when brought into the home? How do these products reflect both the changing nature of domestic foodscapes and the extension of entertainment space into the heart of the kitchen? Finally, what does the rapidly expanding category of fun foods reveal about both child/parent perspectives on food and domestic preparation and consumption rituals? Starting from the perspective that food (and packaging) messages are highly symbolic, I suggest that a reading of fun food transforms our understanding of the domestic foodscape by drawing attention to three themes—entertainment, empowerment and experience—that have silently entered the home along with these products.

Fun Foods in Focus

4 Fun foods are important to the domestic foodscape for, like all supermarket goods, their first (if not final) destination is the home. But this is the most trivial reason for examining these child-oriented products, as will be addressed shortly. First, however, it is necessary to briefly profile the symbolic messages conveyed by fun foods—both in terms of packaging and the foods themselves.

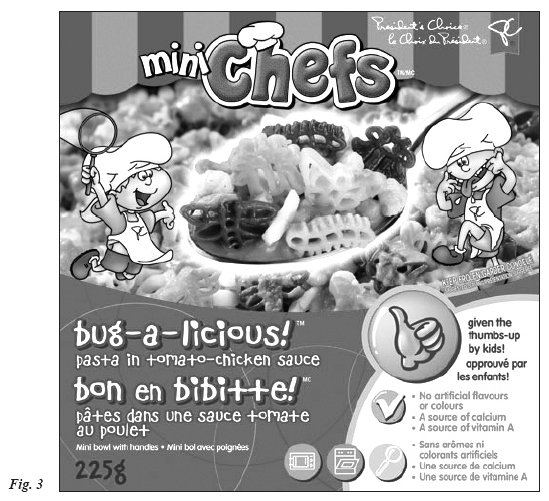

5 When considering children’s food in the supermarket, many people first think of the cereal aisle, where cartoon characters grace boxes of colourful Froot Loops and the fun consists of watching the milk turn pink. But children’s food has moved beyond the cereal aisle, and the play is becoming much more elaborate. A recent study on the marketing of children’s food in Canadian supermarkets revealed that almost ninety per cent of fun foods coded fell outside of the breakfast foods category (Elliott 2008). Fun foods now populate the dairy, beverage, frozen foods and entire dry goods categories; they can be found in packaged meals, yogurts and cheeses, fruit snacks and boxed crackers. Beyond individual products, entire brands and sub-brands have recently emerged that insert “kids” right into the brand name: Loblaws’ Presidents Choice Mini Chefs line and Safeway’s Eating Right Kids stand as representative examples, as do the brands of BoboKids and Nature’s Path EnviroKidz.

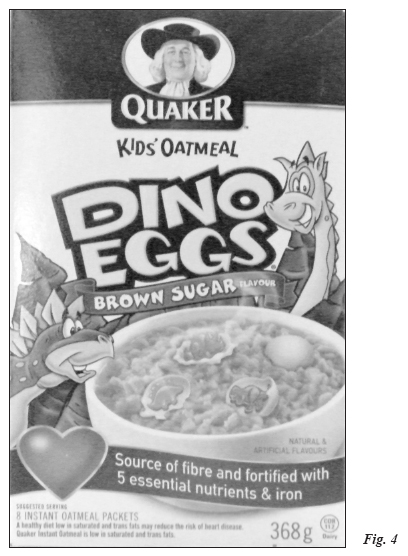

6 Be it a brand in itself or individual products within a brand, fun foods attract children with more than colourful packages: the foods themselves are often strangely shaped, wildly coloured and may transform in terms of shape, size or hue. In the Canadian supermarket, children (and parents) do not merely select between Tony the Tiger and Toucan Sam, they are wooed by Secret Agent Stew, Banana Blast Milk 2 Go and “Kaboom” flavoured yogurt. They select from pink bug shaped noodles, smiley face fries, tattooed waffles and “gushing” fruit snacks. Even more, they encounter packages that stress “magical” themes or foreground interactive qualities. Quaker’s Dino Eggs Instant Oatmeal contains mini dinosaur eggs in the oatmeal that “hatch” into coloured sugar dinosaurs with the addition of boiling water. Betty Crocker’s Tongue Talk Tattoo Fruit Roll-Ups have “tattoos” painted right on the fruit snack (that children can dye their tongues with), and Nabisco’s Ritz Dinosaurs frame crackers as the way to “get the kids entertained.” Even yogurt has entered the world of both magic and fun. Yoplait Tubes (marketed as Go-Gurt in the United States) are portable yogurt tubes that have camouflage designs or reveal secret access codes as the product is consumed. Yoplait’s Kosmo Koolberry tubes actually glow in the dark—the package instructs children to hold the tubes up to the light for two minutes and then go into the dark to watch the tubes glow.”1

Entertaining Eats

7 Fun Pix waffles, tattooing fruit snacks and dino-hatching oatmeal: it is important to scrutinize these “regular” foods turned “fun” because the semiotics of fun foods—what the food communicates— has significant implications for the domestic foodscape.

8 In their recent analysis of children’s food marketing, Juliet B. Schor and Margaret Ford argue that contemporary marketing of children’s food pivots on the symbolic message of “cool,” which includes oppositional themes, anti-adult themes, or drug themes (2007: 16). The cool factor, they affirm, has been extended to children’s food. Respectfully, I disagree. Although children’s food is oppositional, it is the funning of food—the shift to playfulness, not to coolness—which makes kids food distinct. Without question, fun foods are explicitly coded as “fun” to children. Packages are brightly coloured, use cartoon graphics and fonts and frequently reference fun on the box. Sometimes the very names of the foods are fun—as with Mini Chefs Funshines Biscuits, Sun-Rype FunBites, Eggo’s Fun Pix (Fig. 1) or Black Diamond’s Fun Cheez.

9 Unusual product names or flavours—Alphatots or Kaboom yogurt—equally reflect this shift to playfulness. Thematically and conceptually, fun is both constructed and implied through product names and flavours that rely heavily on onomatopoeia, unlikely juxtapositions and elements of transgression or rebellion—onomatopoeia such as chocolate Splat pudding, Strawberry Splash fruit gushers or Zap’ems three cheese pizza. Unusual juxtapositions such as Rainbow Rush “windable” fruit snacks, and yogurt tubes in the unlikely flavour of Volcanic Blueberry, Cyber Strawberry and Hip Hop Grape. Or even cheese strings that sound so much more fun due to their primary label as Cheddarific or Marbelicious. Suggestions of transgressiveness or rebellion in the product name also connote the notion of fun (as opposed to the staidness of the adult world)—such as Betty Crocker’s Tongue Talk Tattoo Fruit Roll-Ups (Fig. 2) or the variety of products that reference bugs or explosions.

Fig. 1

Display large image of Figure

1

Display large image of Figure 2

10 What is the significance of bringing these entertaining eats into the home? First, a strict (decontextualized) reading of fun food suggests that family style dining and meals from scratch, as idealized in representations of the 1950s home, must truly be a relic of the past. Yet, in her social history of domestic science, Perfection Salad: Women and Cooking at the Turn of the Century, Laura Shapiro points out that women have long been encouraged to use packaged foods and “modern conveniences” in domestic food preparation (1986: 4). During the First World War, the “domestic science movement”—a push to apply the scientific method to the production and preparation of food—gained a stronghold as part of the war effort to conserve food (218). As Shapiro reveals, the movement had other aims as well: “scientific cookery” was not merely a means to nourish, but also helped to support the food industry and to standardize tastes (192). Domestic science helped to usher in and promote a range of processed convenience foods—Jell-O salad, ketchup and processed cheese all had their origins in the movement—and the advertising industry artfully promoted the use of these mass-market foods as the true mark of the “modern housewife” (191-92). By the postwar era, the expression “scientific cookery” had lost popularity, but the focus on convenience certainly had not. The postwar food industry promoted instant food as the “housewife’s dream” (Shapiro 2004: 1-40), liberating her from the drudgery of cooking and saving valuable time. This era witnessed both the Can-Opener Cookbook and NBC’s new Home Show, where the “cook” Poppy Cannon, showed viewers how to make vichyssoise “with frozen mashed potatoes, one leek sautéed in butter, and a cream of chicken soup from Campbell’s” (2004: 4).

11 Shapiro argues that in the postwar era, “time became an obsession” (62) with advertisers seeking to promote their products. The resulting discourse was one that emphasized “high speed cookery”:“If you’re a typical modern housewife, you want to do your cooking as fast as possible,” wrote a columnist at Household magazine who was promoting instant coffee and canned onion soup. Not even cold cereal got to the table fast enough. According to Kellogg, what mothers really liked about the new Corn Pops was that the cereal was presweetened, a boon they found to be a great time-saver....“It’s just 1-2-3, and dinner’s on the table,” exclaimed a story in Better Homes & Gardens. “That’s how speedy the fixing can be when the hub of your meal is delicious canned meat.” The five menus included several recipes of a type that would become legendary in the annals of packaged-food cuisine, including “Twenty Minute Roast”—wedges of Spam glazed with orange marmalade.... (Shapiro 2004: 63)Not all housewives, cooks or television shows embraced the “Jell-O, marshmallow and mayonnaise” approach to food preparation, and Shapiro clearly details the struggles between the champions of “real” cooking (embodied by the likes of James Beard) versus those of food assembly (promoted by Poppy Cannon). The incessant promoters of high-speed cookery had to carefully ensure that the homemaker, even as she sought to save precious moments, still felt that she meaningfully contributed to the dinner she served her family. The solution was to underscore the creativeness of package-food cuisine, positioning it as a means of nourishing the family, minus the drudgery.

12 Shapiro’s work draws attention to the fact that packaged foods have been part of the domestic foodscape for some time. Family meals have, for decades, regularly included processed convenience foods, even if it was simply the classic lime Jell-O and cabbage side dish or the tuna casserole made with Campbell’s condensed mushroom soup. This notion of saving time by using such foods has become increasingly central to domestic meal preparation. Arlie Hochschild’s The Time Bind (1997) details how parents in the 1990s experience the encroachment of work hours on their family lives. Women are not merely spending more hours at the office, but paid work is silently taking over life at home as well. Packaged goods solve what the corporate world has made the working mother’s problem, Hochschild argues. Ready-to-serve lasagna combined with a freshly tossed salad and garlic bread, and the family meal is complete. Indeed, recent surveys on Canadian food habits and behaviours reveal that more than 70 per cent of Canadians identify “convenience” and “ease of preparation” as either significant or “very important” when it comes to choosing foods to eat (CCFN 2006: 48), suggesting that the focus on packaged convenience goods and time saving which started decades ago is very much a part of contemporary domestic food consumption.

13 What is different today, however, is the focus of contemporary packaged goods. Fun food, in particular, with its array of frozen Buzz Lightyear shaped chicken nuggets, and breaded nuggets stuffed with macaroni and cheese2 (not to mention contemporary “TV dinners” aimed specifically at children) is much different from the Spam and marmalade twenty minute roast featured in the 1950s Better Homes & Gardens article Shapiro (2004: 63) wrote about. Prepared food of previous decades focused on the family meal with some assembly required (i.e., marmalade-glazed Spam is clearly intended for the family); yet Bug-a-licious pasta is a prepared dinner for a child only. This suggests that dinner has, in fact, become fractured with children eating separate meals from their parents. Breakfasts, lunches and snacks, too, can conceivably be prepared solely with the offerings of fun food: a breakfast of Eggo Fun Pix waffles tattooed with images of Hannah Montana; a lunch of Heinz Bob the Builder pasta, with Dare Bear Paws cookies and Sponge Bob Squarepants Aqua Kids water or Kool-Aid Jammers; and snacks of Sun-Rype Funbites, Madagascar-themed Dunkaroos or PC Mini Chefs Funshines Biscuits. The significance is not simply about fun (a point that will be addressed shortly) but about visibility: fun food makes the child present in the domestic foodscape in a way not seen before. A child embedded in a family community blends in—meals are consumed by all. But fun food separates the child from the family unit and creates a unique space where the symbolic value of consumption is markedly different. Eating becomes not ritual or a form of family communion (Barber 2007: 105), but entertainment for the child.

Edible Empowerment

14 This idea of separate meals for children raises the interesting question as to why parents would be willing to serve such products to their children while, in the process, forfeiting the logic that one meal/snack suits all. This is not because mothers have abandoned the notion of domestic cooking. Indeed, research indicates that women still consider cooking—particularly cooking dinner—as an act of caring for the family’s emotional and social well being (Bahr Bugge and Almas 2006: 211). However, fun food brings two standout offerings to the modern table. First, it validates the concept of the child as a unique cultural category. Second, it limits any possible parental/domestic guilt for not preparing meals from scratch. Each of these aspects will be dealt with in turn.

Validating the Cultural Category of Childhood

15 While the idea of the child as a unique cultural category can be traced back to mid-18th-century Europe (Aries 1962), it is only in the last decades of the 20th century that children became directly targeted as consumers (Kapur 2005). By the 1970s, children were recognized as a “primary market” (McNeal 1999: 16) with distinct needs and characteristics. McDonald’s Happy Meal was introduced in 1977, singling out an entirely new target market, while marketers in all product categories flock to the theme of empowerment to justify the new gate crashing that is going on.3 James McNeal’s Kids as Customers (1992) and The Kids Market (1999) affirm that the primary goal of targeting children directly is to “satisfy more kids” (1999: 11). Dan Acuff’s (1997) What Kids Buy and Why: The Psychology of Marketing to Kids equally insists that promoting products to children is a means of empowering them, since products can “contribute in some significant way toward an individual’s positive development” (18). Even marketing candy to children can be an empowering experience, according to Acuff, because such products give children the opportunity to learn “to make the right choices under the watchful and concerned guidance of informed parents and caretakers” (19). Such discourse plays on the agency of the child, acknowledging children not as adults-in-waiting, but as agents in their own right (O’Sullivan 2005: 371).

16 Some cultural critics observe that this form of empowerment is really a colonization of children’s play and imagination (Saunders 2006: 84). Others suggest that childhood itself is being effaced by these cultural developments. As we learn from the work of Ellen Seiter (1993), Chris Jenks (1996), David Buckingham (2000) and others, the social construction of childhood is always defined in opposition to adulthood. This is what Buckingham labels “the politics of exclusion”—because children “are defined principally in terms of what they are not, what they should not know and what they cannot do” (2000: 14).

17 What remains disturbing for so many adults is that one consequence of empowerment plays out in children crossing the line. This is a phenomenon Neil Postman (1994) expounds upon in his alarmist but engaging book, The Disappearance of Childhood. Postman’s core argument is that the contemporary media of late modernity, particularly television, has eroded the distance between childhood and adulthood. Children have entered the “adult world” in terms of their entertainment, their dress, their understanding of “adult secrets” such as sex—and this has occurred primarily because television is so easily accessible. One does not need any special knowledge or education to access television. And so, for Postman, childhood has disappeared—and this research is noteworthy because, in many ways, it represents the dawn of studies that suggest that childhood is somehow disappearing or transforming—from Chris Jenks’ article on the “strange death of childhood” (1996) and David Buckingham’s (2000) After the Death of Childhood to Jyotsna’s Kapur’s (2005) analysis of childhood’s radical transformation due to technology. Benjamin Barber’s (2007) Consumed, conversely suggests that the push comes from the other direction, with adults becoming increasingly childlike in their tastes, preferences and behaviours. What we are left with, here, is a group of young people who are not unlike adults at all, in terms of knowledge, attitude, consumer preferences, technological savviness and worldly exposure. But I would suggest that as these distances between adulthood and childhood become crossed—whether through technology or other cultural processes—new distinctions are created to reinforce the difference between adult and child, which is precisely what we are witnessing in the world of children’s food.

18 Fun food works to clearly carve out the separate space for childhood that other cultural developments may have eroded. It validates the cultural category of childhood by affirming that certain foods are specifically for them, that adult fare does not fulfill children’s particular culinary needs. Perhaps children are simply small “empowered” consumers exposed to adult secrets—but the category of fun food stands to reaffirm that there is still a clear difference between adult and child tastes and consumables. Fun food is an instant identifier of children’s space and taste.

The Issue of Domestic Guilt

19 Beyond validating the specialness of childhood, fun food also assuages parental guilt over serving packaged goods. As earlier noted, women still view their efforts in the kitchen as “an important indicator” of motherliness, and regard cooking as an act of caring for the family (Bahr Bugge and Almas 2006: 11). Food manufacturers from the 1950s onward assured homemakers that convenience goods were still merely part of the domestic cooking scene— as such, glazing Spam with marmalade or adding extra ingredients to pre-packaged cake mix was still an expression of creativity in the kitchen. So how is it possible that packaged children’s foods become acceptable in domestic space? They are acceptable because it is not possible to make bug-a-licious pasta, glow-in-the dark yogurt tubes or dinosaur-hatching oatmeal in the kitchen. The vibrant colours and magical qualities of fun food—which claim to reinforce what it means to be a child—are utterly un-creatable in the domestic kitchen.4 In purchasing fun food products, and thereby validating the unique culinary needs of the child, parents also relieve themselves of any possible guilt over not making the foods themselves—because they are simply unable to do so (Fig. 3).

The Fun Food Experience

20 Fun food offers entertainment and empowerment for children. Equally, it presents a novel experience which cannot be found in everyday or fast food consumption practices. Consider, first, the thematic of fun. Children’s foods stake claim to the fun of the consumption experience, manifest through the wild names, flavours and colours and direct appeals to fun on the package. PC Mini Chefs Zookies claim to “make snack time fun,” as do Pepperidge Farm’s rainbow coloured Goldfish crackers, Betty Crocker’s Fruit Gushers and Nabisco’s Dinosaur Ritz. General Mills’ Fruit by the Foot rolls out three feet of tie-dyed entertainment, with a backing papered with games and jokes. The fun is premised both on the artificiality and interactivity of what is being consumed (which, again, makes these foods impossible to recreate in the domestic kitchen while distancing them from adult fare). The fun food experience, however, is premised on the concept of the video game or television screen.

Fig. 3

Display large image of Figure 3

21 Children’s culture is populated by video games with advanced graphics, high definition televisions, instant messaging, flashy websites and the like—so it is not surprising that children’s foods have assumed characteristics of the other communication that fills their lives. The little coloured “hatching eggs” in Dino-Eggs oatmeal (Fig. 4) is not merely a unique selling proposition and a way to distinguish between parity products, but is also a reflection of the interactivity and sense of play expected of children’s consumer goods. Here the entertainment is presented so as to be both played and consumed; the audience (in this case the child) can approach the table with the expectation of being amused. Ours is, after all, a society of entertainment, for adults as well as for children; perhaps food as entertainment is simply another indicator of the degree to which this ethos has informed every aspect of our existence. Fun food thus extends entertainment space into the heart of the kitchen, but without the use of the television. Making eating more enjoyable, vibrant and interactive, fun food offers precisely the two features—interactivity and a focus on content—that analysts claim to be of core interest to today’s generation of children (Lindstrom et al. 2003: 3).

22 A second aspect of the fun food experience is that as supermarket fare, it is intended to be brought into the home. Consider the distinction between fast food and fun food. Fast food has been labelled “the emblem of American style consumerism” (Barber 2007: 103); its essence “is not what it is but how it is: its speed, to which everything else … is linked” (103). The fast food experience typically occurs outside the home, and is much loved by children not merely for the tastes, but also for the informality of the eating process and the ways that rituals of dining are temporarily suspended (we can eat with our hands, off of paper wrappings and not plates, etc.). McDonald’s Happy Meal plays on this informality, even adding a toy to heighten the fun. Fun food similarly offers the suspension of dining rules and rituals. Informality, in fact, is a necessary corollary of (fun food) play; one cannot be made to use a spoon for yogurt when it comes packaged in a tube designed for squirting straight into the mouth! Thus, adult rules, manners and canons of behaviour surrounding food are bent, offering children a form of empowerment. Unlike fast food, however, fun food is not predicated on speed. With fun food the “Happy Meal” has essentially been brought into the home to be consumed leisurely, its accompanying “toy” bursting forth from the food itself. Perhaps the most revealing feature of fun food lies in its relationship with preparation and consumption rituals. With fast food, the food is prepared quickly and consumed quickly. Speed in preparation is acceptable for a meal consumed outside the home, while on the go. Fun food is equally quick to prepare (it is packaged food, after all)—but it is consumed in domestic space, where more leisurely food rituals previously dominated. In the case of fun food, as the preparation becomes more succinct, the consumption becomes more elaborate. Play takes time; it is not to be hurried. This is far removed from Brian Wansink’s Mindless Eating (2006), which warns adults of distracted eating patterns such as eating in front of the computer or while watching television. On the contrary, fun food urges children to pay attention to eating. The whole point is mindfulness, but mindfulness based on play.

Fig. 4

Display large image of Figure 4

23 Still, this raises the question of why parents would be willing to embrace the idea of fun food—certainly there have always been strategies to make children eat, but there is a pointed difference between creating “ants on a log” by topping celery sticks with peanut butter and then raisins, and serving up pink bug-a-licious pasta and beverages that “magically” change colour. The difference, I suggest, is between ornamentation versus artificiality. Stuffing celery with peanut butter and raisins is a form of ornamentation—it takes natural, identifiable ingredients and combines them to create something more elaborate. Serving colour-changing beverages, dino-hatching oatmeal or fruit snacks that magically dye your tongue unnatural shades of blue is premised, instead, on artificiality and the entertainment that such artificiality (strangely) promises.

24 In an era that has witnessed the rapid growth of organics, the slow food movement and “buy local” campaigns, as well as consumer wariness around genetically modified foods, trans fats and additives, how is it that the extreme artificiality of children’s food—even if framed as a mindful entertainment experience—has managed to thrive and gain acceptance by parents? The answer is complex, and most certainly reflects (as earlier discussed) the recognition of the child as a distinct consumer requiring special, targeted goods. Fun food also reflects the ways that the child has come to stake out an increasingly centralized place in the family unit—the everything-for-the-child sensibility, which means, along with the purchasing of numerous toys and designer clothing, the selection of special foods and child oriented meals. Parents accept this, perhaps, when they work long hours and do not have the time (or the inclination) to create and sit down with a home cooked meal. Perhaps children’s foods provide another way for parents to deal with the guilt of work days that are too long and that leave limited time for play—because the play can occur during the eating experience, and under the watchful eye of mom or dad. Fun food is a means of providing enjoyment that requires little exertion from the parents.

Entertainment, Empowerment, Experience: The Kitchen as Playroom and a New Mindful Eating

25 The cultural significance of food, including its role in identity creation, status formation and boundary marking, has been explored from a range of scholarly perspectives. Food is a symbol, not merely sustenance; it “always has a social dimension of the utmost importance” (Douglas 1982: 124). Food’s symbolic dimension, furthermore, receives an extra configuration when brought into the home, into private, domestic space. I have argued that the symbolic value of fun food resides in its promotion as entertainment, empowerment and experience for children. Fun food carves out a space which affirms the unique preferences and tastes of children while establishing their symbolic distance from the world of adult foods. That these are supermarket foods matters, since their first (if not final) destination is the home. Bringing fun food into the domestic foodscape shifts the essence of the meal or snack. It creates a bubble for children’s own (transgressive) food rituals, whether they’re eating alone or seated with adults, and transforms the kitchen table into a tasty playroom. While adults may be repelled by the types of edibles characterizing fun food—green yogurt, blue fries, purple ketchup, pasta bugs—fun food fosters in children a very different kind of mindful eating. It is eating, not while distracted, rather as distraction itself. A paradox arises because there is a mindfulness demanded by fun food, but it is a mindfulness far removed from appreciating food’s origins. (Appreciating origins is an adult concern.) Instead, fun food encourages children to be mindful of consumption because it promises an extension of play.

26 Within the domestic foodscape, then, fun food becomes a vector for play, an assertion of the sensory “difference” of childhood and a recognition that entertainment should extend to even the most mundane of activities. The taste for fun food is not merely literal, but visceral. Indeed, it is an artificial, interactive and edible experience, which extends childlike pleasure into the heart of the domestic foodscape.

References

Acuff, Dan. 1997. What Kids Buy and Why: The Psychology of Marketing to Kids. New York: The Free Press.

Aries, Philippe. 1962. Centuries of Childhood. London: Jonathan Cape.

Bahr Bugge, Annechen and Reidar Almas. 2006. Domestic Dinner: Representations and Practices of a Proper Meal Among Young Suburban Mothers. Journal of Consumer Culture 6 (2): 203-28.

Barber, Benjamin. 2007. Consumed: How Markets Corrupt Children, Infantalize Adults, and Swallow Citizens Whole. New York: W. W. Norton.

Buckingham, David. 2000. After the Death of Childhood. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Canadian Council of Food and Nutrition (CCFN). 2006. Tracking Nutrition Trends VI. Woodbridge, ON: CCFN http://www.ccfn.ca/pdfs/TNT_VI_Report__2006.pdf (accessed January 19, 2009).

Douglas, Mary. 1984. Food in the Social Order. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Elliott, Charlene. 2008. Marketing Fun Food: A Profile and Analysis of Supermarket Food Messages Targeted at Children. Canadian Public Policy 34 (2): 259-74.

———. 2008a. The Strange, the Bizarre and the Edible: Artificiality and Fun in the World of Children’s Food. In Communication in Question: Canadian Perspectives on Controversial Issues in Communication Studies, eds. J. Greenberg and C. Elliott, 81-88. Toronto: Thomson-Nelson.

Gates, Kelly. 2006. Tempting Tummies. Supermarket News 54 (44): 39-48.

Hochschild, Arlie. 1997. Time Bind: When Work Becomes Home and Home Becomes Work. New York: Metropolitan Books.

James, Allison. 1998. Confections, Concoctions, and Conceptions. In The Children’s Culture Reader, ed. H. Jenkins, 394-403. New York: New York University Press.

Jenks, Chris. 1996. Childhood. London: Routledge.

Kapur, Jyotsna. 2005. Coining for Capital: Movies, Marketing and the Transformation of Childhood. London: Rutgers University Press.

Lindstrom, Martin, Patricia Seybold, Nigel Hollis and Yun Mi Antorini. 2004. Brandchild: Insights into the Minds of Today’s Global Kids: Understanding Their Relationship with Brands. London: Kogan Page.

McNeal, James U. 1992. Kids as Customers: A Handbook of Marketing to Children. New York: Lexington Books.

———. 1999. The Kids Market: Myths and Realities. Ithaca, NY: Paramount Market Publishing.

O’Sullivan, Terry. 2005. Advertising and Children: What do the Kids Think? Qualitative Market Research Journal 8 (4): 371-84.

Postman, Neil. 1994. The Disappearance of Childhood. New York: Vintage.

Rose, Kristin. 2007. Kids’ Snack Attack. Prepared Foods 176 (3): 23-28.

Saunders, Eileen. 2006. Good kids/bad kids: What’s a culture to do? In Mediascapes: New Patterns in Canadian Communication, eds. P. Attallah and L. Shade, 77-94. Toronto: Nelson.

Schor, Juliet and Margaret Ford. 2007. From Tastes Great to Cool: Children’s Food Marketing and the Rise of the Symbolic. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics 35 (1): 10-21.

Seiter, Ellen. 1993. Sold Separately: Children and Parents in Consumer Culture. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press.

Shapiro, Laura. 1986. Perfection Salad: Women and Cooking at the Turn of the Century. New York: Henry Holt.

———. 2004. Something from the Oven: Reinventing Dinner in 1950s America. New York: Viking.

Wansink, Brian. 2006. Mindless Eating: Why We Eat More Than We Think. New York: Bantam.

Notes