At Home and Away:

Newfoundland Mummers and the Transformation of Difference

Diane TyeMemorial University of Newfoundland

1 It is a time of great change in Newfoundland and Labrador. The collapse of the northern cod stocks has resulted in so much out-migration that since the cod moratorium was announced in 1992, more than 65,620 people have left the province.1 Few young Newfoundlanders with marketable skills remain in rural areas; only the elderly hang on. Trepassey, on the Avalon Peninsula, serves as just one example. Thirteen hundred and seventy-five people lived there when the fish plant closed in 1991; by 2006 there were 889 remaining residents. The school closed, as did the pub, while the local arena struggled to remain open according to a 2002 Globe and Mail newspaper article by Kevin Cox.2 As he prepared to leave home for a university program to equip him for employment in the offshore oil industry, twenty-nine-year-old Gordon O’Neill from Trepassey told Cox, “I love the water and everything around here. It’s home...[but] There isn’t any work here. I’d be working now if there was” (Globe and Mail 2002). Notwithstanding promising reports of an economic upturn in Newfoundland and Labrador,3 university students in my folklore classes at Memorial University of Newfoundland echo O’Neill’s views. All know people who have moved away from Newfoundland and Labrador for employment; many have family and friends who commute to other parts of the country, if not the world, for work. The students, too, are resigned to moving from their home communities.

2 With such massive social change, Gerald Pocius argues “the belonging of place has given way to the objectification of culture onto certain expressive forms” (Pocius 1991: 23). He claims that for many people, including those forced by economics to leave their homeplace, symbols of Newfoundland and Labrador now embody home. Once the necessity to share space is removed, people are forced to create new images of culture based on things rather than on obligation within shared spaces. Once people decide to leave places, culture becomes objectified. In Newfoundland generally, there is increased interest in a select group of items—stories, songs and objects that are believed to embody the essence of indigenous values. (1991:25) Within this discourse, Christmas mummering, also known as mumming or janneying, has become “the collective identity symbol for Newfoundland’s nativistic movement” (Pocius 1988: 76). Here I reflect on the mummer as a pivotal transitional image for a rural Newfoundland diaspora and I explore it as a primary symbol for a lost rural way of life and the vanishing “real” Newfoundland. How do representations of mummers on wrapping paper, coffee mugs, art prints or Christmas tree ornaments give material shape to a distinct regional character and evoke a particular sense of home place?

Strange Mummers

3 As Gerald Pocius has argued elsewhere, the objectification of mummering as a unique aspect of Newfoundland tradition dates to the 1960s when academics not originally from Newfoundland focused attention on it (Pocius 1988; Smith 2007). Amid the academic interest that helped transform mummering from a custom that was considered nearly dead to what Elke Dettmer describes as “all but a fixation for cultural research in Newfoundland” (1993: 129), Herbert Halpert and George Story’s 1969 publication of Christmas Mumming in Newfoundland emerged as the defining collection of essays. Halpert conceived of the anthology in 1963 after he attended a lecture on jannying by anthropologist Melvin Firestone. When the volume was published six years later it contained articles by scholars in anthropology, folklore and English. Halpert’s typology of mummering as indoor or outdoor, formal or informal, along with the volume’s historical and anthropological discussions, became the foundation for contemporary academic understanding of mummering in Newfoundland.

4 Looking back at Christmas Mumming in Newfoundland, one is struck by the variety of mummering practices. Although Halpert’s “A Typology of Mumming” in Newfoundland emphasizes the house visit, his classification includes several other forms such as formal outdoor movement—the parade and formal indoor performance—the play. Anthropologist, Louis Chiaramonte also warns against oversimplifying the custom. In his exploration of mummering in Deep Harbour on the south coast of Newfoundland, he distinguishes ten types of mummering groups, encompassing both adults and children, that correspond to social and age cohorts within the community (1969: 90).

5 Publications through the 1980s reinforce this sense of diversity in both historic and contemporary mummering practices. In his exploration of 19th-century mummering, Cyril Byrne draws on the account of Reverand Phillip Tocque. Remembering his boyhood experiences in Carbonear ca. 1825, Tocque describes for the Evening Telegram (February 10, 1897) two kinds of adult mummers, as well as boy mummers who Byrne interprets as enacting a version of a mummer’s play: Then there were the mummers—those who went around by day and those who went round by night. The day mummers—the men had white shirts over their clothes, trimmed with ribbons, with fanciful hats. Each man had a partner—a man dressed in women’s clothes. Into whatever house they entered they recited their lessons, ea [sic] and drank, had a dance, their own fiddle [sic] playing the tunes. The night mummers were dressed in the most grotesque manner: some with humpbacks, cow hides and horns projecting, with hobby-horses, small bags of flour, which they used to throw over their followers. Then there were the boy mummers, who went around day and night. On two Christmases I had John Bemister as a partner. He acted as the Duke of Wellington, and I impersonated Oliver Cromwell. (Byrne 1981: 3) Mummering drew on a cross section of the population rather than “the lower orders” as later commentators suggest. Tocque’s father was a successful merchant and his friend’s father was John Bemister, a merchant who later became Colonial Secretary (Byrne 1981: 4).

6 Margaret Robertson’s 1984 analysis of mummering practices in 343 communities during 1965 and 1966 points to provincial variation in nearly every aspect of the mummer’s house visit, including group composition, disguise, entertainment and food. In some communities both men and women, usually of around the same age, went mummering together; in other places, only men went out. Where all-male groups were prevalent, the practice was rougher, with displays of strength and occasional fighting according to Robertson (160). In some locations, she noted that mummering had degenerated into a children’s custom, much like Halloween, although she clarified that in the past mummering would have been primarily an adult practice and form of entertainment (11). In two-thirds of communities where both men and women went mummering, their disguise involved gender reversal; women dressed as men and men dressed as women. But mummers could also disguise themselves as “characters”: an elderly person, a fisherman, minister, doctor, bride, ghost, devil or hunchback. Occasionally, animal costumes were worn, especially if a cow, sheep or goat had been slaughtered for Christmas.

7 Robertson found that hobby horses also appeared in some locations (107). As the hobby horse suggests, mummering could be playful or ominous. In some places mummers were loud, playing tricks and deliberately scaring people encountered along the way. It was not unusual that one group of mummers be chased by another. Robertson found that in parts of the province it was common for mummers to fight as they went from house to house; it could be a time to settle grudges (55). Mummering might be accompanied by heavy drinking; in other places, no alcohol was involved.4 This variation in mummering activities is supported since 1995 by the experiences of students in my folklore classes. Depending on where one is from, different segments of the population mummer: men, women, young people and/or children. They may behave more or less aggressively, dress and entertain differently and be served a variety of food and drink.

8 Of these mummering practices, academic studies have tended to focus on the house visit rather than the stylized mummers play. For example, Robertson begins her monograph The Newfoundland Mummers’ Christmas House-Visit, by chronicling her own shift in interest from the play, for which she turned up very few texts, to the mummer’s house visit. She writes: The house-visit had flourished in Newfoundland at least from the early twentieth century and possibly earlier, until the nineteen-sixties. In contrast to the folk play, it was well remembered and so was its context, Newfoundland outport Christmas and the way of life of which it had been a part. (1984: xiv)From Halpert to Robertson, academic analyses highlighted the 1960s as a golden age of traditional culture and emphasized how mummering illuminated the community dynamics of a lost era. Mummering both violated and affirmed community values. Robertson (1984) found that it afforded people licence and temporary release from gendered identity roles and community responsibilities. The freedom offered by disguise could lead to open confrontation. At the same time, ethnographers noted that mummering brought people together to socialize and allowed them to accomplish practical tasks such as organizing crews for the upcoming fishing season (Faris 1969; Sider 1977).

9 Academics emphasized the mummer’s strangeness: for example, the mummer was a threatening bogey-man-like figure that could be used by parents as a form of social control over children (Firestone 1969; Widdowson 1973). In fact, according to anthropologist Melvin Firestone, mummers and strangers were social equivalents. He argued that both strangers and mummers knocked and their identities were to be determined: “Someone must go to the door to see to them as one would see to a stranger.... Their knocking is a ritual by which they announce their strangeness.” (70). Firestone believed that with unmasking, mummers were transformed from strangers into familiar friends in a dramatic affirmation of community membership. It was a ritual of trust (Palmer and Pomianck 2007). Just as the cockfight was Clifford Geertz’s key text to understanding Balinese culture (Geertz 1971), mummering became central to folklorists and anthropologists in their study of Newfoundland. They embraced it as a metaphor for the Redfieldian “folk community” (Redfield 1960) they sought in rural Newfoundland; yet, it also spoke loudly of the social distance separating non-Newfoundland academics from their subjects.

10 Chris Brookes was one of the first of Newfoundland’s artists to be inspired by the academic attention on mummering. Brookes established a local theatre group first called the Mummers, and later the Mummers Troupe, in response to what he saw as academic neglect of the mummers play in favour of the house visit. Beginning in 1972, the troupe annually performed a composite version of the play, drawn first from Christmas Mumming in Newfoundland and later from their own fieldwork on the Southern Shore (Pocius 1988: 62). They performed the play in private homes in St. John’s in an effort to bring back to the people what they saw as an indigenous form of working-class theatre (Pocius 1988: 62). Identifying mummering as a vehicle to raise the cultural consciousness of Newfoundlanders (Pocius 1988: 61), the Mummers Troupe contributed to the transformation of mummering from a collective communal tradition to that of a symbol of regional identity (Dettmer 1993: 46). With the mummers play as their springboard, the Troupe went on to produce a series of political plays that addressed social and cultural issues from industrial disease to the seal hunt, that earned them the claim of being “English Canada’s foremost political theatre, the first anglophone company to use theatre as a technique of direct intervention in community struggle” (Filewod 1988: 127).

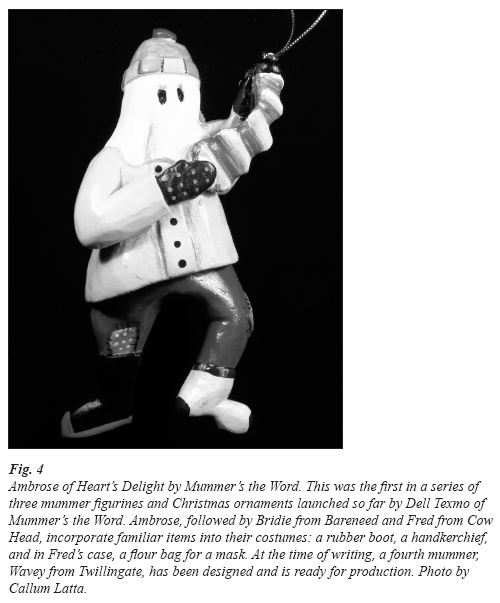

11 Visual artists also looked to mummers for inspiration. For example, pewtersmith Raymond Cox5 gave Halpert’s typology new life in sculpture. Born in Connecticut, Cox studied with American pewter designer, Frances Felten before travelling to Newfoundland in the mid 1970s to enroll in a Masters program in folklore. While Cox never completed his folklore degree, he was influenced by Halpert’s work on mummers. The stylized mummers created by Cox years later in his Quidi Vidi Hand Wrought Pewter Studio, are very much a material manifestation of his academic training: a range of shapeless forms representing varieties of mummers and mummering practices in the province. Hobby horses and swords give the figures an ominous feel. Cox’s recognition of the violence associated with some aspects of the mummering tradition is evidenced by one of his products, a mummer’s licence. This relates to a specific moment in Newfoundland’s history when violence—eventually resulting in death—led to the outlawing of mummering. The tag that accompanies the licence created by Cox quotes the Newfoundland Legislation of 1861 that banned public displays of mummering following the murder.

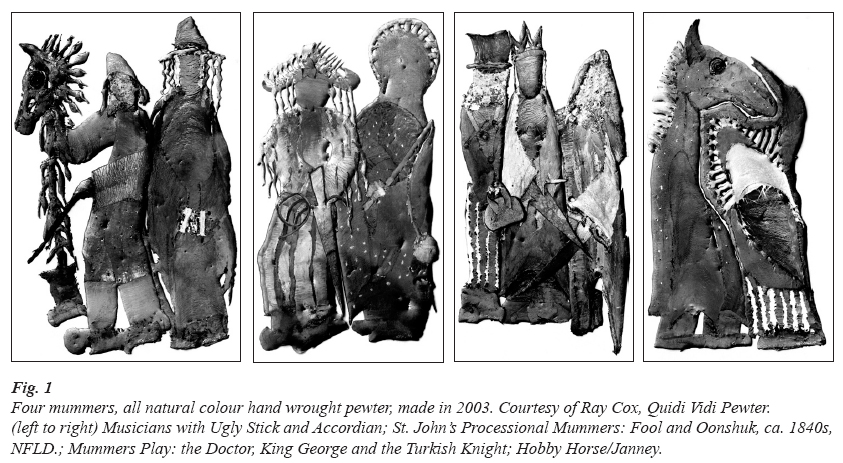

Fig. 1 Four mummers, all natural colour hand wrought pewter, made in 2003. Courtesy of Ray Cox, Quidi Vidi Pewter. (left to right) Musicians with Ugly Stick and Accordian; St. John’s Processional Mummers: Fool and Oonshuk, ca. 1840s, NFLD.; Mummers Play: the Doctor, King George and the Turkish Knight; Hobby Horse/Janney.

Display large image of Figure 1

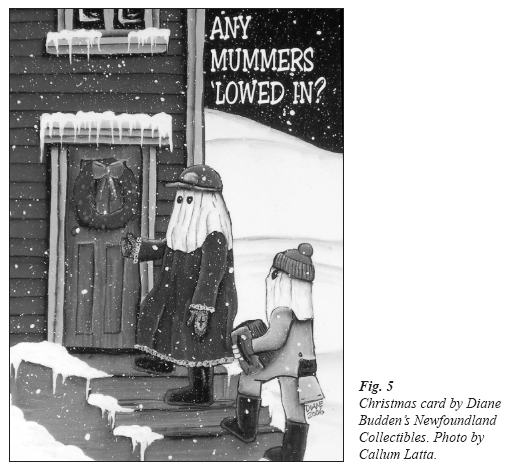

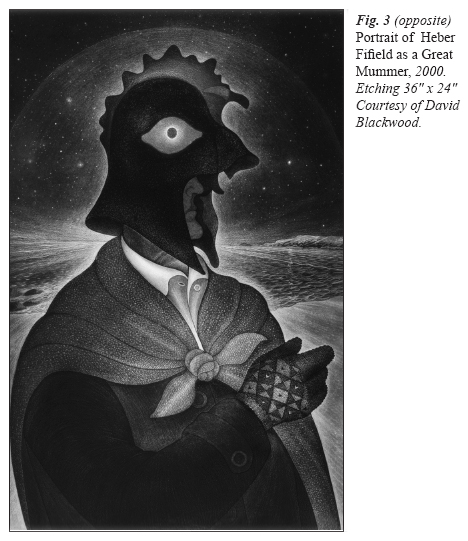

12 David Blackwood, one of Newfoundland’s most well-known artists, has also reproduced the strangeness of the mummer in his prints. For the past three decades, Blackwood, who was born in Wesleyville, Newfoundland in 1941 and who still maintains a studio there, has created eerie, often solitary, images of mummers, hiding ghostlike behind veils. Commenting on the importance of mummering to the Christmas festivities in Wesleyville, Blackwood observes: It was something everyone wanted to do—I started mummering myself when I was five years old. I remember the fun of it, but also the powerful sense of mystery—the eeriness of faces transformed by veils, the moonlit figures that were strangely familiar wandering through the night, the feeling that you were participating in something incredibly ancient—a ritual as old as life itself. (2003: 2)Blackwood would agree that mummering served as a mechanism whereby delicate community issues could be addressed. He recalls that not only would mummers take it on themselves to settle accounts for wrongs committed, but also that a mummer mediator could bring resolution to a festering community matter, arrange amorous liaisons and deliver marriage proposals (3-4).

13 In writing of Blackwood’s art, William Gough describes how Blackwood uses the magic and mystery of the everyday, the lace doily and house frock, to create these spirit-like mummers (2001: 88). Gough notes, however, that there is a shadowy side to mummering, a side Blackwood also captures in one of his prints—with the depiction of the death of a mummer on the ice between houses.

14 As is characteristic of Blackwood’s printmaking, his mummers are dark; one can feel the cold of the winter night as these mysterious figures move from house to house. There is no visible camaraderie binding Blackwood’s mummers even when they travel in groups.

Happy Mummers

15 Today, reproductions of mummers are popular at crafts markets and tourist shops across the province. In a recent article, Paul Smith (2007) identified twenty-six different categories of commodification of Newfoundland mummers ranging from the non-material-like events and recordings to a wide selection of artifacts: paintings and illustrations, commercial prints, sculptures and figures, dressed dolls, clothing, tote bags and wine bags, greeting cards, postcards and notecards, Christmas tree ornaments and gift wrapping paper. These representations do not reflect the diversity of the custom as recorded by academics, and they stand in stark contrast to the strangeness of Cox’s shapeless forms and Blackwood’s ghostlike images. Mummers in crafts and souvenir shops are uniformly happy—carefree, yet connected. Less descendants of Halpert’s work, they were more inspired by images of mummers in Simini’s hit song, “Any Mummers Allowed In,” commonly known as simply “The Mummers Song.” Released in December 1983 by Simini (Bud Davidge and Sim Savoury), a band from Newfoundland’s Fortune Bay, the song was immediately and wildly successful. Songwriter, Bud Davidge recreated key but positive images from mummering—the knock, the disguise, the heat. Two years later these images took expression in the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation Television program, A Fortune Bay Christmas. This Christmas special has been replayed each Christmas for the last sixteen years, making it a familiar and much anticipated seasonal program. Gerald Pocius credits the popularity of “The Mummer’s Song” to its appeal for two groups of Newfoundlanders: those who had mummered uninterruptedly and for whom it was a source of pride, and those with nostalgia for their past. Regardless of the audience, however, “the impact of Simini’s song on a local cultural practice was profound” (Pocius 1988: 80). According to Pocius, Simini’s song led to a revival of mummering in parts of the province where it had died out and for many Newfoundlanders, “Any Mummers Allowed In” became a requisite accompaniment for the mummering experience. Importantly, the song has become an accepted representation of what mummering should be. It is “the” popular text; to mummer now means to disguise in the manner presented in the song, knock, use ingressive speech and essentially, to behave as the song suggests mummers behave. And there are no signs that the song is losing popularity. On November 27, 2007, Paul Raynes—host of VOCM Radio’s Good Morning Show in St. John’s—observed that “Any Mummers Allowed In” remains one of three Christmas songs most requested by listeners and that the station receives numerous requests for it each day leading to Christmas.6

Fig. 2 (left) Mummer Family at the Door, 1985. Etching 36″ x 24″ Courtesy of David Blackwood.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 3

16 In contrast to Blackwood’s frozen and/or solitary figures, the Simini-inspired mummer that decorates hasty notes or tote bags is not alone, but “one of the crowd.” He or she travels in groups of two or three or more, a party of sufficient size to provide protection for one another, but not large enough to be dangerously rowdy. These are friendly mummers, propping one another up as they stagger along, perhaps feeling the effects of too much alcohol as they trudge through thick snow. They show each other the way—and the way leads home. Newfoundland homes, lights glowing and warm, are a key, almost essential element in popular depictions of mummers. Houses beckon refugees from the cold night; hosts are always welcoming.

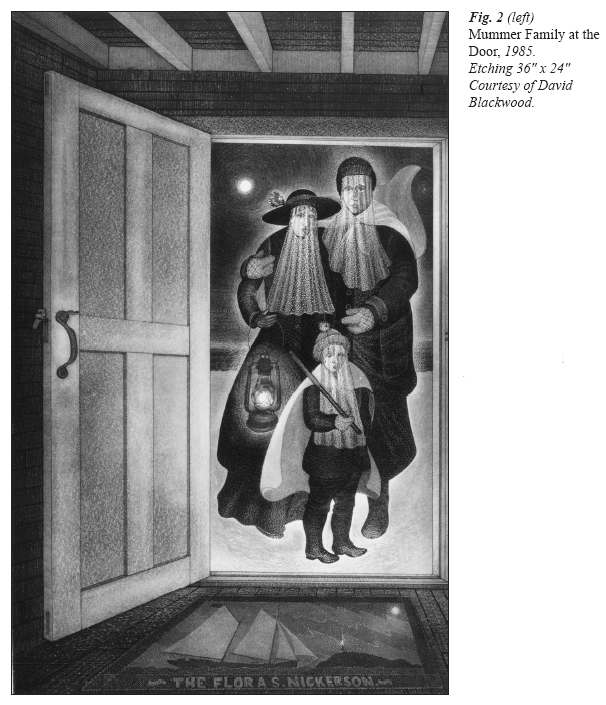

17 In 1984 Robertson found that while mummers’ costumes varied widely, they were made from materials at hand. The all-important mask, for example, was often a lace curtain from the bedroom or kitchen window, held in place by a hat (18). Other times a disguise was fashioned from a pillowcase, a flour or sugar sack or from a cardboard box, paper bag or stocking. Today’s depictions of mummers, whose disguise is crafted from a lace doily or curtain, a cotton sugar sack, a checkered tablecloth or a Newfoundland traditional mitten, powerfully evoke the familiarity of homeplace through the material culture of everyday life in Newfoundland and Labrador a decade or two ago. Through mundane items of childhood, mummers transport today’s consumers back in time to their own homeplace; their childhood home.

18 These popular representations celebrate the house visit form of mummering and in doing so they frequently depict the kitchen, the heart of the Newfoundland home. A place of warmth and light when the rest of the house in winter was unheated and dark, it was a site of sociability; mummers, carrying musical instruments or dancing, become interchangeable with the informal kitchen party, another signature of rural Newfoundland traditional culture. This is not mummer as stranger, or loner, or persecutor of children, but as a warm, hospitable and jovial community member. The mummer of popular culture conflates custom and party. Like the kitchen party, the mummer represents generosity, sociability, the sharing of music, food and a good time. This is the “real Newfoundland”—simple, rural, hospitable and friendly. It is the best of a remembered childhood: a warm kitchen, laughter and Christmas memories. There is no room here for any child’s terrified response to the mummers’ entry.

19 The mummer’s success as a symbol for Newfoundland culture is due, in no small measure, to its appeal to the many Newfoundlanders living away from home. One crafts store worker I spoke with confessed that first-time visitors to the province often are puzzled by the lumpy figures and confused by slogans like “Mummerville” that identify the picture of a mummer on a hand-made mug. She must act as their guide. On the other hand, rural Newfoundlanders for whom mummering is still a part of their Christmas season have no need to surround themselves with reminders in the form of wrapping paper and tree ornaments when the real thing is at the door. If mummering is not ongoing, they are willing to let it be replaced by other more evocative markers of their life. They do not require an objectified reminder of their place because they are there. Consequently, mummers and mummering seem to speak most loudly of homeplace to the Newfoundlander who is away from home, in need of images and objects to construct a sense of belonging. For those born in rural Newfoundland and Labrador who were forced to leave the small isolated communities of their birth for growth centres during Premier Joey Smallwood’s resettlement programs of the 1960s and 70s, or for the thousands who have left the province in search of employment in the decades since, the papier mâché ornament or doll dressed as a mummer mediates displacement and belonging. It symbolizes home as both a place and time existing only in memory for those away from home who yearn not just for the place, but also for that moment in time they left behind. Like the academic discussions that celebrated the 1960s as the golden age of traditional culture, expatriates look back to the years of their childhood as golden. Popular depictions of mummers and kitchen parties embody the specialness of Newfoundland culture and way of life. They draw from, and build on, underlying assumptions of the Newfoundland cultural revival of the last thirty years that the distinctiveness of Newfoundland culture lies in its rural communities (Overton 1996: 49).

Getting Some Mummering on the Go

20 In his work on the development of Newfoundland tourism, James Overton (1996) points to the promotion of nostalgia as an important theme in provincial advertising, particularly when the campaigns are aimed at expatriate Newfoundlanders.7 He writes:There are strong similarities between the meaning of the return visit for expatriates and pilgrimages. For many migrants, as for many members of particular religious groups, everyday life is lived in exile, in a profane space away from the sacred centre from which much of life’s real meaning is drawn. Pilgrimage and the return visit are important…. Thus for many “existential tourists” the journey’s goal is an almost indefinable one of travelling towards a spiritual centre, a sacred space in the migrant’s memory. For many emigrants the Newfoundland of the mind is a metaphor: it represents tradition, the past, community, the sacred. In a temporary visit, one can celebrate the positive aspects of community, even though this may be a largely mythical community constructed in the memory of the exile. (131) In this context, mummering can become a fitting metaphor for the expatriate experience. The apparent stranger is welcomed unconditionally and with the revealing of his or her identity, is accepted as one of the community’s own. It is as if they never left—they only looked different for a moment. In some communities mummering has become a kind of homecoming ritual.8 Ironically, in the face of the brisk market for images of mummers, students in my classes repeatedly refer to mummering as “dying out” in their communities and often report having to search their childhood memories for mummers’ visits.9 Yet, they sometimes describe a recent bout of mummering initiated by an expatriate home for Christmas.10 With the lead of the visitor, then, mummering is revived, sometimes in communities where it has not been practised for some years. As Boniface and Fowler write, “Deep down, a lot of people travel to arrive where they are from. And if it’s improvement on the reality, hyper-real, an idealized version ... so much the better” (1993: 13). Whereas Margaret Robertson reported dozens of incidents of fighting as mummers travelled from house to house (54), today the custom more often seems to mediate difference than express conflict. Mummering signals to Newfoundlanders that this is “home” for, in case there is any doubt, the tote bag and the coffee cup tell us, mummering is Newfoundland. To mummer is to experience, or to go to, what Erik Cohen (1979: 181) calls “the spiritual centre.” To know one is “home,” one goes mummering, or at least buys a mummer’s image and, by extension, experiences the warmth of family and community that the image typifies.

21 Perhaps it is not surprising that expatriate Newfoundlanders have embraced mummers and mummering as a symbolic representation of their homecoming.11 Chiaramonte (1969: 81) wrote of mummering’s effectiveness in breaking the separateness of households and John F. Szwed (1969: 113) emphasized mummering’s utility as an opportunity to extend one’s ties through food and drink exchanges. Melvin Firestone’s analysis of the mummer as stranger revealed to be strange no more, fits the circumstance of the former resident who may at first seem unfamiliar, but who sees himself to still be one of them. Perhaps decades later, mummering continues to offer Newfoundlanders what Rex Clark described in the 1980s as “a collective, class struggle, aimed at preventing such a separation of capital from labour, or—and this amounted to the same thing—the disjunction of summer and winter” (Clark 1986: 18). Although the economic realities of rural Newfoundland have changed over the last two decades, labour is arguably even more removed from capital as fishers sell their catches to foreign markets, and ever more rural residents commute to Alberta and other parts of the mainland. Maybe mummering still gives participants a voice in their class struggles, as Clark argued was the case in the 1980s, and continues to create a romantic and utopian vision that helps to sustain rural residents in their struggles for food, affection and for knowledge (19). For Gerald Sider (1977: 15), mummering helped restore egalitarian relations among families who fished together but who may have gone their own ways during the winter months. He saw mummering as an activity that allowed rural residents to gain some control over the social relations that went into producing fish, even if they did not control the actual means of production. As rural communities adjust to declining population and to residents commuting to work in other parts of the country, and even the world, mummering may continue to offer what Sider described as “a social, community-wide, and egalitarian framework for the redistribution of work relations, for introducing a controlled flexibility in the ties that bind people together as kin, clan, neighbors and co-workers” (26).

Fig. 4 Ambrose of Heart’s Delight by Mummer’s the Word. This was the first in a series of three mummer figurines and Christmas ornaments launched so far by Dell Texmo of Mummer’s the Word. Ambrose, followed by Bridie from Bareneed and Fred from Cow Head, incorporate familiar items into their costumes: a rubber boot, a handkerchief, and in Fred’s case, a flour bag for a mask. At the time of writing, a fourth mummer, Wavey from Twillingate, has been designed and is ready for production. Photo by Callum Latta.Fig. 5 Christmas card by Diane Budden’s Newfoundland Collectibles. Photo by Callum Latta.Mummers and Strangers

22 Overton argues that the “real Newfoundland,” is constructed through the processes of idealization and romanticization. He writes:Specifically, the images that are stressed are those emphasizing such characteristics of the people as strength, pride, independence, fortitude, individualism, respect for the past, love for the environment, freshness, vitality, hospitality, simplicity, generosity, kindness, openness. The “people” are “happy,” they have “great community spirit,” they enjoy the good life and above all they have real culture. (1996: 106)He continues, “Elements from people’s pasts are incorporated into the vision, however, especially childhood memories, as childhood is for many something of a golden age of innocence compared with adult life” (129). Similar to greeting cards or ornaments of the mummer, homeplace becomes an object. The mummer on a tote bag or beer bottle label mediates between the displaced Newfoundlander’s childhood home and his present one; between the (partly) imagined simplicity of the traditional past and complexities of modern life. Time and space are compressed as the mummer brings an idealized past forward and gives abstract ideals concrete form.

23 Newly arrived academics at Memorial University in the 1960s turned to mummering in the creation of an intellectual homeplace and they distanced themselves from their subjects through an Othering process; mummers were strangers, entities as foreign to the newly arrived as the place itself. Today, it is images of happy mummers with their positive links to an idealized past that enjoy popularity. They sell very well. However, both strange and happy mummers mediate differences—academic and subject, displaced Newfoundlander and birthplace—and help to create an imagined homeplace, whether academic or remembered. Such constructions of homeplace must be approached critically. Like Overton, I cannot help but worry about the implications of this post-tourism nostalgia, which he sees as indicative of current alienation (129). Certainly, in a time when Newfoundland is emptier than it has been for centuries, the longing for a lost past is a less direct critique than many other challenges politicians could face.

References

Bella, Leslie. 2002. Newfoundlanders: Home and Away. St. John’s, Newfoundland: Greetings from Newfoundland.

Blackwood, David. 2003. Mummering in Newfoundland. In David Blackwood: The Mummers Veil, March 29-April 13, 2003. An exhibition catalogue. Oakville, ON: Abbozzo Gallery.

Boniface, Priscilla and Peter J. Fowler. 1993. Heritage and Tourism in “the global village.” London & New York: Routledge.

Byrne, Cyril. 1981. Some Comments on the Social Circumstances of Mummering in Conception Bay and St. John’s in the Nineteenth Century. The Newfoundland Quarterly 77 (4): 3-6.

Chiaramonte, Louis J. 1969/1990. Mumming in “Deep Harbour”: Aspects of Social Organization In Mumming and Drinking. In Christmas Mumming in Newfoundland, eds. Herbert Halpert and G. M. Story, 76-103. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Clark, Rex. 1986. Romancing the Harlequins. A Note on Class Struggle in the Newfoundland Village. In Contrary Winds: Essays on Newfoundland Society in Crisis, ed. Rex Clark, 7-20. St. John’s, Newfoundland: Breakwater.

Cohen, E. 1979. A Phenomenology of Tourist Experiences. Sociology: The Journal of the British Sociological Association 13(2): 179-201.

Dettmer, Elke. 1993. An Analysis of the Concept of Folklorism with specific Reference to the Folk Culture of Newfoundland. PhD diss., Memorial University of Newfoundland.

Economic and Statistics Branch, Department of Finance. 2007. Regional Demographic Profiles Newfoundland and Labrador. Government of Newfoundland and Labrador.

Faris, James C. 1969. Mumming in an Outport Fishing Settlement: A Description and Suggestions on the Cognitive Complex. In Christmas Mumming in Newfoundland, eds. Herbert Halpert and G.M. Story, 128-44. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Filewod, Alan. 1988. The Life and Death of the Mummers Troupe. The Proceedings of the Theatre in Atlantic Canada Symposium, ed. Richard Paul Knowles,127-141. Anchorage Series 4. Sackville, NB: Centre for Canadian Studies, Mount Allison University.

Firestone, Melvin. 1969. Mummers and Strangers in Northern Newfoundland. In Christmas Mumming in Newfoundland, eds. Herbert Halpert and G. M. Story, 62-75. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Geertz, Clifford. 1971. Deep Play: Notes on the Balinese Cockfight. In Myth, Symbol and Culture, ed. Clifford Geertz, 1-31. New York: W. W. Norton.

Gough, William. 2001. David Blackwood: Master Printmaker. Vancouver and Toronto: Douglas & McIntyre.

Halpert, Herbert. 1969. A Typology of Mumming. In Christmas Mumming in Newfoundland, eds. Herbert Halpert and G. M. Story, 34-61. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Halpert, and G. M. Story, eds. 1969. Christmas Mumming in Newfoundland. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Overton, James. 1996. Making a World of Difference. Essays on Tourism, Culture and Development in Newfoundland. St. John’s: Institute for Social and Economic Research.

Palmer, Craig T. and Christina Nicole Pomianck. 2007. Applying Signaling Theory to Traditional Cultural Rituals. Human Nature 18(4): 295-312.

Pocius, Gerald L. 1988. The Mummers Song in Newfoundland: Intellectual, Revivalists and Cultural Nativism. Newfoundland Studies 4(1): 57-85.

———. 1991. A Place to Belong: Community Order and Everyday Space in Calvert, Newfoundland. Athens & Montreal: University of Georgia Press and McGill-Queen’s.

Redfield, Robert. 1956/1960. The Little Community and Peasant Society and Culture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Robertson, Margaret R. 1984. The Newfoundland Mummers’ Christmas House-Visit. Ottawa: National Museums of Canada.

Sider, Gerald M. 1977. Mumming in Outport Newfoundland. Toronto: Hogtown Press.

Smith, Paul. 2007. Remembering the Past: The Marketing of Tradition in Newfoundland. In Masks and Mumming in the Nordic Area, ed. Terry Gunnell, 755-811. Uppsala: Swedish Science Press.

Szwed, John F. 1969. The Mask of Friendship: Mumming as a Ritual of Social Relations. Christmas Mumming in Newfoundland, eds. Herbert Halpert and G. M. Story, 104-18. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Widdowson, John D. A. 1973. Aspects of Traditional Verbal Control: Threats and Threatening Figures in Newfoundland Folklore. PhD diss., Memorial University of Newfoundland.

Notes