Visitors’ Voices: Lessons from Conversations in the Royal Ontario Museum’s Gallery of Canada: First Peoples

Cory WillmottSouthern Illinois University Edwardsville

Résumé

Quelques jours avant Noël 2005, le Musée royal de l’Ontario organisa l’inauguration, « réservée aux membres », de la toute nouvelle galerie des Premières nations. Assistant à cet événement en compagnie de l’un des conservateurs, j’ai eu l’opportunité unique de voir de l’intérieur les stratégies de conservation à l’arrière-plan de l’exposition, tout en étant en même temps en bonne position pour entendre les remarques non censurées des visiteurs qui regardaient cette exposition pour la première fois. Cette circonstance a suscité le dialogue sur des questions de fond telles que la redéfinition du concept « d’aire culturelle », comment surmonter le stéréotype de « l’Indien en voie de disparition » ou la réévaluation des avantages et des inconvénients des dioramas, autant que sur les contraintes générées par des administrateurs soucieux des finances et les équipes de designers professionnels pas toujours fiables. La réflexion sur ces questions attire l’attention sur l’importance d’atteindre le public des enfants au moyen de ces expositions et d’élaborer des cadres comparatifs pour les récits postmodernes des expositions contemporaines. Cet article utilise les commentaires des visiteurs comme point de départ de la discussion de ces questions.Abstract

Several days before Christmas 2005, the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) held a “members only” opening for their new First Peoples gallery. Attending this occasion with one of the curators, I had the unique opportunity to gain an inside view of the curatorial strategies behind the exhibit, while simultaneously positioned to overhear the uncensored remarks of visitors as they first encountered the show. This circumstance stimulated dialogue on such central issues as redefining the “culture area” concept, overcoming the “disappearing Indian” stereotype and revisiting the pros and cons of dioramas, as well as the constraints of finance-minded administrators and unreliable professional design teams. Reflection on these issues draws attention to the importance of reaching children through exhibits and of establishing comparative frameworks for the postmodern narratives of contemporary exhibits. This article uses visitors’ comments as a springboard for a discussion of the above issues.1 Several days before Christmas 2005, I met with Royal Ontario Museum’s (ROM) curator Trudy Nicks for lunch and a guided tour of the new First Peoples gallery. This exhibit is among several developed as part of the reconceptualization of the institution in accordance with architect Daniel Libeskind’s vision of a crystal-like projection that has been grafted onto the building. It is the first time in twenty-five years that the ROM has had a permanent exhibit space for its First Peoples collections. On the day of my visit, these new galleries were open only to museum members for a special preview. Nicks explained that the First Peoples gallery was not yet finished. Many of the shelves, stands and inside walls in the exhibit cases remained empty because the graphics company had been slow to produce the images for installation behind the artifact displays. For the same reason, most of the labels that identified and interpreted the individual artifacts were missing.1 Undaunted and anxious to capitalize on the holiday traffic, the ROM administration decided to forge ahead with the members’ preview and the official opening that followed on December 26.

2 The unusual circumstances of this occasion—the curatorial tour, the members’ preview and the unfinished state of the exhibit—provided unanticipated opportunities to reflect on some of the central issues facing anthropology curators today. In the mid-1980s, multifaceted critiques simultaneously gave rise to a “New Art History” (Phillips 2002; Vastokas 1987) and a “major paradigmatic shift in museum anthropology” (Hedlund 1994: 33). This permanently transformed the way that art and anthropology curators approach the representation of First Nations art and artifacts. Because scholars in both disciplines have recognized an indispensable need to incorporate the approaches of each other’s disciplines, I shall refer to the interdisciplinary result as the “new museum anthropology/art history.”

3 Probably the single most important characteristic of the new museum anthropology/art history is that it responds to critiques from members of the cultures and nations whose art and artifacts are represented by exhibits. For the curators, the transformed vision of the First Peoples gallery addresses changes posed by First Peoples’ critiques of museum practice. Yet, the new gallery’s very existence has come about as the result of the transforming visions of the ROM’s administration, evidenced by the thorough renovation and expansion of the buildings in order to “modernize” the institution’s image. Thus, at the outset there were three strong constituent voices that shaped the exhibit—the ROM administration, the ROM curatorial team and the aboriginal activists, artists, scholars and curators who have participated in the dialogue with museum professionals over the past fifteen or so years. Curiously, the one major voice missing from this polyvocal process is that of the museum-going public. While touring the exhibit, Nicks and I had occasion to overhear visitor comments and to engage in dialogues with patrons. These experiences provided an opportunity to add voices from the public—albeit, after the fact.

4 In this article, I will quote and analyze the visitors’ comments we encountered on our tour in terms of the interpretive frameworks patrons brought with them to the First Peoples gallery, emphasizing how these relate to various historic and current anthropological strategies of representation. I will then evaluate the exhibit’s potential to achieve the goals of its educational message, and conclude by suggesting ways in which exhibits of aboriginal art and artifacts may refine their educational message once the public has been introduced to the general principles of the new paradigm. Overall, I suggest that the new principles of representation have potential for promoting better understandings between Native and non-Native peoples that surpasses that of previous paradigms. Each paradigm shift, however, has also entailed lost opportunities. In this new era, these may be recovered with some focused attention if financial shortages can be surmounted.

Impressions and Conversations from the Tour of the Gallery

5 The overheard comments and the encounters Nicks and I had with numerous visitors highlighted some of the obstacles curators face in their efforts to bring museum scholarship forward into the 21st century. Most of the visitors we spoke with, and/or overheard, were thoroughly engaged with the artifacts in the cases. Their major frustration was the fact that there were no labels. Although a temporary shortcoming, it is instructive to have the importance of labels confirmed. Visitors really do read them! Perhaps not all labels, but those for the artifacts they find most interesting. Strangely, there were no signs posted explaining the unfinished state of the exhibit, or to guide visitors to the two binders—one in each rest area—that contained the text for all the artifacts in the gallery. The binders, however, were not exactly “user-friendly.” Even we had difficulty finding the record for an artifact that was of interest to us.

6 Besides satisfying visitor curiosity, labels serve the very important function of interpreting the artifacts and images in the exhibit. The need for interpretation became evident when Nicks and I were inspecting the Evelyn Johnson exhibit in the Great Lakes case. Evelyn Johnson was sister to the famous Mohawk author, E. Pauline Johnson. Nicks was pointing out that the Plains-style moccasins owned by one of Johnson’s brothers, as well as the northwest coast artifacts that E. Pauline Johnson wore in her stage performances, suggested that the family participated in the late-Victorian culture of curio collecting. Suddenly we overheard a woman (Visitor A) behind us complaining: I’m not here to learn about white people. I am white! I want to know about Natives. Where does this tell us about Natives?The irony of this statement is that the woman was standing in front of a portrait of Evelyn Johnson wearing a European style dress. Since there were no images or artifacts pertaining to “white” people near where she was standing, it appears that she mistook Johnson for a non-Native person. This visitor’s reaction forces us to confront the fact that museum goers are well-trained in the conceptual framework of our predecessors in which “Indians” were exotic Others stuck in the “ethnographic present.” Visitors are accustomed to gaze upon the Other from a distance that denies intercultural interaction. They are unprepared to encounter First Peoples who are essentially like themselves and living in historic time. Visitor A was so embedded in the self/other dichotomy that the lack of “Indian” signifiers in Johnson’s portrait led her to assume that Johnson was white. Moreover, in a more general sense, Visitor A’s lack of interest in Native/non-Native relations shows that she does not see herself in an historical relationship with Native peoples, perhaps not only because past ethnographic exhibits denied it, but also because that story implicates non-Natives in ways that create an undeniable moral discomfort.

7 It is remarkable just how effectively those ethnographic present exhibits and displays really did educate, not only about Native peoples, but especially about a particular way of looking at them. I have no doubt that Visitor A’s reaction was common to an entire generation who grew up with such museum displays. Visitors come to ethnographic exhibits with the interpretive framework that they learned as children. Is it possible that, with labels and time, the audience can be re-trained to comprehend, and even embrace, anthropologists’ new perspectives? Unfortunately, we will never know whether reading the label that will, when installed, identify Johnson as a Mohawk woman would have inspired a revelatory moment for Visitor A. Would it have had the intended effect of decentreing her assumptions and thereby opening her mind towards accepting the new historically-contextualized framework?

8 The ROM’s new First Peoples gallery provides many such opportunities for visitors to shed their previous assumptions and adopt new understandings precisely because, as anthropologists, members of the curatorial team know all too well the interpretive framework that haunts these exhibit halls from within the minds of visitors. They can therefore anticipate visitors’ misinterpretations and strategize ways to build bridges to new visions. With regard to the individual objects, however, it is not always evident to curators exactly what sort of interpretation visitors need in order to make sense of the artifacts in front of them. This point was illustrated to us when a woman (Visitor B) and her husband (Visitor C) approached us with questions about an Ojibway cradleboard in the Subarctic display case. They were confused about the materials used to make it and wanted to know how it was used to carry a baby. After years of exposure to cradleboards, I have become so familiar with them that I see their materials and manner of use as self-evident. It is one of the intriguing things about human nature that we don’t generally recall the myriad stages through which we learned something, but rather our knowledge accumulates and becomes embedded in a matrix of the ways-things-are. Consequently, I would not have thought it necessary to demonstrate these features. Thus, inherent knowing can be a deterrent to understanding—even a problem—for a public that lacks the benefit of such accumulated knowledge.

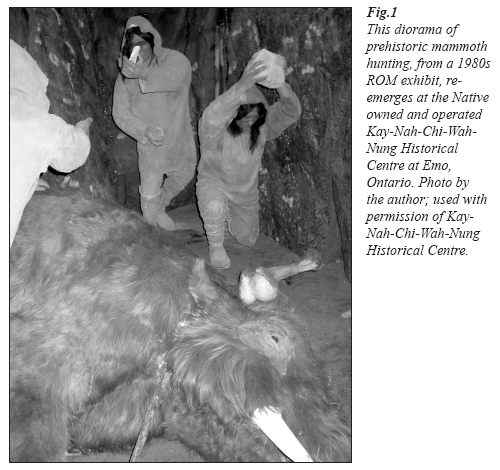

9 The cradleboard was problematic to Visitors B and C. Not surprisingly, then, they drew upon their recollection of their learning processes to help solve the problem. The husband of the pair observed:It’s harder to understand how the artifacts would have been used since they don’t have the plaster figures anymore. And then, in a joking-like manner, he continued:But they still have some bare breasts over there, so I guess it’s okay.As was the case with Visitor A, the old ethnographic exhibits are once again haunting the gallery. Yet, Visitor C does have a point. At the very least those dioramas, or “life groups,” demonstrated very forcefully how the artifacts therein were used, whereas the cradleboard sitting upright by itself on a grey modular platform does not. After their initial introduction to America at Chicago’s Worlds Columbian Exposition in 1893 (Jacknis 1985: 81; Hinsley 1981: 108), dioramas were adopted almost universally among North American museums as a revision to the evolutionary framework in which objects were displayed by types and in series of evolutionary development, often without regard for their cultural specificity (Chapman 1985: 31-33). Interestingly, while dioramas are losing favour among museum scholars, displays whose dioramas are modeled after individuals in Native communities—such as at Mille Lacs Indian Museum in Minnesota, the Milwaukee Public Museum, Wisconsin, and the Mashantucket Pequot Museum in Connecticut—are popular among members of their respective communities who speak with pride of the models.2 At the Mashantucket Pequot Museum, which is Native owned and operated, visitors walk through ahigh-tech 22,000-square-foot “immersion environment” diorama… [They] can walk among chestnuts, oaks and maples, through wigwams, and past handcrafted figures shown in cooking, talking, weaving and working poses… All figures were cast from Native American models, and the clothing, ornamentation and wigwams were made by Native craftspeople.3 Like Visitor C, I too can remember the ROM’s old dioramas from my childhood. Many of the figures were dressed scantily in rough uncut and unsewn animal hides which gave the whole group the appearance of “primitivism” and “savagery.” The political inappropriateness of these exhibits caused the ROM to dismantle them many years ago. Ironically, Nicks and I happened to be on a field trip together during a conference in Kenora, Ontario,4 when we encountered a reincarnation of figures from the ROM’s 1980s Prehistory gallery dioramas installed at the Native-owned and operated Kay-Nah-Chi-Wah-Nung Historical Centre at Emo, Ontario. Here, one diorama of prehistoric mammoth hunting is virtually identical to its original version (Fig. 1). In another diorama, the figures wear garments made by the renowned elder and former community member Maggie Wilson who Ruth Landes made famous in her ethnography, The Ojibwa Woman (Landes 1938) (Fig. 2).

Fig.1 This diorama of prehistoric mammoth hunting, from a 1980s ROM exhibit, re-emerges at the Native owned and operated Kay-Nah-Chi-Wah-Nung Historical Centre at Emo, Ontario. Photo by the author; used with permission of Kay-Nah-Chi-Wah-Nung Historical Centre.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 2

10 One reason for the popularity of dioramas among Native peoples is that the content, in some contemporary examples, is more in tune with images Native peoples have of themselves than were the representations shown in non-Native institutions. For example, at the Milwaukee Public Museum the models are wearing powwow regalia and dancing in a Grand Entry Procession exactly as happens at an actual powwow today. In the diorama at Kay-Nah-Chi-Wah-Nung Historical Centre, Maggie Wilson’s dress speaks of family and community pride. As the late Mohawk curator and historian Deborah Doxtator (1996: 65) pointed out, the fifteen to twenty aboriginal-operated museums in Canada have different aims and approaches from those of the larger mainstream institutions. In particular, as components of integrated community-based initiatives that address local cultural, spiritual and social needs, aboriginal-operated museums tend to focus on their own communities, involve local elders extensively in their programming and provide storage space for ceremonial items that community members may remove for use in the celebration of rituals, customs and sacred observances. In this context, dioramas are able to convey new understandings to audiences that may differ from those of urban mainstream museums. Informal conversations with Native acquaintances lead me to believe that it is also possible that, unlike the highly educated members of the Native arts and academic communities, at the local community level many Native people continue to be influenced by favourable impressions of dioramas from their childhood experiences of museums. Whereas critiques of anthropologists per se have been popularized within Native communities, critiques of museum anthropology in particular are still somewhat confined within academic circles.

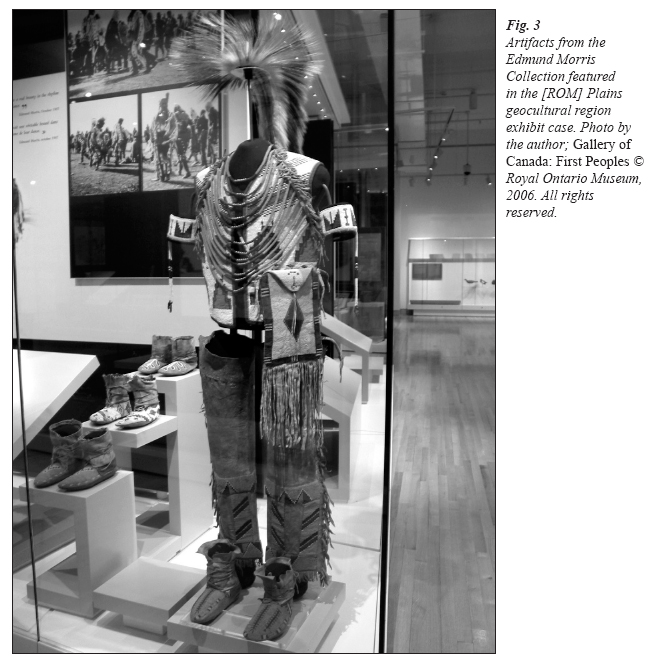

Fig. 3 Artifacts from the Edmund Morris Collection featured in the [ROM] Plains geocultural region exhibit case. Photo by the author; Gallery of Canada: First Peoples © Royal Ontario Museum, 2006. All rights reserved.

Display large image of Figure 3

11 The popularity of dioramas in Native owned and operated museums leads me to wonder whether abandoning them places curators in danger of losing opportunities to convey cultural context. Dioramas are certainly too costly and permanent for exhibits that attempt to historicize both the artifacts and the exhibit itself. Recognizing the difficulty of achieving both temporal depth and cultural breadth, the ROM curatorial team chose to focus narrowly on one ethnographic encounter (i.e., one collector) for each region. For example, the Plains exhibit case features artifacts that were collected by the early 20th- century artist, Edmund Morris (Fig. 3). While this strategy does effectively achieve significant diachronic depth and synchronic breadth in terms of the overall storyline, there are still challenges to be faced in answering visitors’ questions about individual artifacts: “What is it? How is it used? Who uses it?” With regard to the cradleboard question, this problem could be solved by placing a photograph of a mother carrying a cradleboard on the wall behind the artifact. The manner of use could even be described in the text of a label. Yet, how could curators know which artifacts would raise such questions and therefore demand such detailed interpretations?

12 There is another issue that arises from Visitor C’s comment. For men of a certain generation, ethnographic displays and images were a “legitimate” form of sexual fantasy. The bare breasts of dioramas were quite possibly among their first encounters with images of naked women. The reason for this seeming moral laxity is that the gaze of the dominant race was joined with that of the dominant gender in the objectification of the Other. Surprisingly, there is a photograph on the Mashantucket Pequot Museum’s website dominated by the bare breasts of a diorama model with her face cropped off. The text belatedly draws attention to the fish bone necklace around the model’s neck.5 Despite the ubiquity of images of naked and/or scantily clad women nowadays, it seems that the sexual potency of the image of the exotic Other still has some currency.

13 Besides these issues of sexuality, Visitor C’s comments provide specific evidence of the power of childhood conditioning for museum visitors. Although said in jest, it is likely that he measured his approval of the exhibit to some extent on the degree to which it met expectations arising from childhood memories. Since I also grew up spending many hours at the ROM, I also viewed the new galleries from this frame of reference. The power of early conditioning was most apparent to me when traversing the newly renovated rotunda where I felt a wave of emotion, accompanied by a flood of memories, rise in my chest. Such emotional responses lead to the expectation that the galleries will inspire the sense of awe and wonderment that one experienced as a child. The intensity of these expectations creates a likelihood of disappointment. What interests me more, however, is the effectiveness of the old museum exhibits to make such indelible impressions on children. Surely it is as desirable for today’s children to be as impressed with the underlying assumptions of the new paradigm as members of my generation were with the old one. What do the interpretive strategies of the new paradigm have to offer children? At the ROM, it appears that children have been segregated to upper floor galleries where, for example, the popular bat cave is located. This impression is further reinforced by the fact that many of the artifacts in both the Asian and First Peoples galleries are displayed on shelves that are too high for children to see.

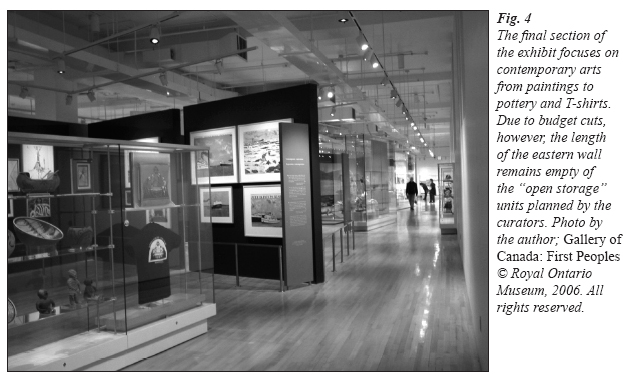

14 The reason for this unfortunate situation became clear to me when reflecting upon my conversation with another visitor (Visitor D) whom I overheard expressing her disappointment over the relatively small size of the archaeology exhibit:Where are all the Clovis and Laurel and Huron stone points?Like Visitor C, she measured the new gallery against her memories of the previous exhibit, but in this case found it lacking. Confused by her jumbled lithic classifications, I attempted to explain that most of the exhibit was ethnological rather than archaeological. Not surprisingly, this explanation did not appear to satisfy her. I motioned her in the direction of the prehistory case, which admittedly appeared dwarfed and overshadowed by the multiple ethnology cases surrounding it. I explained apologetically that the installation was not yet complete. This situation was compounded by the fact that ROM administrators insisted that the show be composed solely of artifacts from its own collections. As the ROM has only Ontario prehis-tory materials, this meant that the curatorial team lacked archaeological materials from all but the Great Lakes geocultural region. Visitor D responded with another question and a comment:Why are there so few objects? We went to another museum where they had drawers full of artifacts and you could open them to see whatever you wanted.I was better prepared to answer this question than the previous one. In the curatorial team’s original design, almost the entire length of the eastern wall was devoted to open storage drawers full of artifacts (Fig. 4). This feature was omitted, however, when the contracted design team’s plan could not be accomplished within their projected budget. I thought it was important for visitors to realize that museums make financial choices that do not always agree with those of their curators. Recognizing that I had a very critical visitor at hand, I anticipated her frustration over the lack of labels and explained the situation to her. Visitor D also had advice on this point: Why don’t they have buttons to press for audio interpretations? That’s what they have in many other museums today.I had to agree that the use of audio interpretations, while effective, is a scarcely-used strategy in Canadian museums. Rather than buttons, however, many museums in England and the United States have hand-held audio devices that look and work much like cell phones. Each visitor receives one on entering the gallery. Of course, this interpretive strategy has a financial component that requires staff to hand out and retrieve the devices. Extra funding is also needed to produce the content material and manufacture the device itself. Needless to say, electronic devices are out of the question for the ROM’s First Peoples gallery given that the budget barely covers regular graphics.

Fig. 4 The final section of the exhibit focuses on contemporary arts from paintings to pottery and T-shirts. Due to budget cuts, however, the length of the eastern wall remains empty of the “open storage” units planned by the curators. Photo by the author; Gallery of Canada: First Peoples © Royal Ontario Museum, 2006. All rights reserved.

Display large image of Figure

4

15 Visitor D’s suggestions also point to another interpretive framework that visitors bring with them to exhibits. She reminds us that some museum visitors could be called “museum connoisseurs.” They participate in the culture of museum-going and develop their own set of criteria for what works and what does not—based on their experiences in a variety of museums and similar institutions. This may be especially true of museum members, but is probably true to some extent of all visitors. This means that, in addition to the memories of exhibits past, visitors enter galleries with expectations drawn from their recent experiences in other museums.

16 These museum connoisseurs are in a position to provide invaluable feedback on the effectiveness of various interpretive strategies. Even the most astute visitors, however, are not necessarily aware of the financial circumstances attending one strategy versus another. As well, they are likely not consciously aware of the conventional typology of museums and how that affects interpretive strategies. If they were, they might possibly notice that audio interpretation devices are most often found with either travelling special exhibits for which additional fees are charged, or in small museums with specialized content that receive a steady flow of paying visitors. Further, audio devices that do not involve individual headsets cannot be employed in a gallery with hardwood floors and an open concept design because of the reverberation of the sound. On the question of open storage, however, Visitor D has a valid point. The omission of this interpretive strategy is disappointing to visitors wishing to see a greater selection of the ROM’s holdings. More importantly, it may have a profound and negative impact on the gallery’s appeal to children. The low height, hands-on functionality and element of surprise characteristic of open storage installations make them excellent means through which new museum anthropology/art history exhibits can convey their transformed visions to children. Being the only child-oriented component in the curatorial team’s original plan, the administration’s decision to pour money into the giant “crystal” projection on the building’s exterior—while claiming insufficient funds to properly exhibit its holdings—may seriously jeopardize the institution’s ability to achieve its educational mission.

17 Gallery of Canada: First Peoples is only one component of a complete overhaul of the Royal Ontario Museum which includes both its building and its galleries. Visitor B (Visitor C’s wife) reminded us of the extent to which museum visitors view individual galleries in the context of their visit to the entire museum. Nicks and I were discussing the birch bark baskets in one of the cases devoted to the processes of culture change. Overhearing the specialized nature of our conversation, Visitor B asked us a question about a grouping of pottery in the case next to where we were standing:Were these pottery designs originally done in textiles?She went on to explain that the motif reminded her of the textile designs she had just seen in the new Asian galleries down the hall. I attempted to explain that there was no need to borrow the designs from textiles. Because they were easily executed with simple tools such as twigs, they could easily have arisen spontaneously in response to the medium. Nicks then explained the storyline of the case: the pre-contact pots were placed next to those of contemporary artists to show the continuity in First Peoples’ artistic traditions. Judging from her facial expression, Visitor B remained skeptical. Rightly so, as in hindsight it appears to me that the people who made the pre-contact pots might have made finger-woven textiles in the same patterns (although it would be futile to ask which came first), but since textiles do not survive the archaeological record, we have no way of knowing that today.

18 More importantly, however, Visitor B’s question draws attention to the fact that visitors rarely visit single galleries in large world-class museums. Rather, they visit multiple galleries and in doing so they may relate variables among galleries. Visitor B’s suggestion actually touches on two major questions in comparative anthropology: What are the processes of culture change? and what is the relationship between material mediums and aesthetic motifs? The First Peoples gallery cannot address these questions of cultural comparison because it is, of necessity, focused on issues arising from the unique political position of Canada’s First Nations. The Asian galleries are similarly oriented toward the interpretation of each particular culture whose artifacts they display. As noted earlier, the structure of the ROM’s galleries results from the shift away from evolution and toward cultural context. Despite the major shortcomings of the evolutionary framework, its display strategies enabled anthropologists to deal with comparative questions. It is somewhat ironic, then, that Boas’s argument that artifacts should be displayed in their own cultural contexts (Jacknis 1985: 79) was based on the same rigorous comparative method through which he arrived at the conclusion that culture change occurred not only through contact (i.e., diffusion), but also through independent invention (Boas 1920 [2000]: 139). Now that our exhibits are entirely culturally discrete we no longer have the mechanisms in place to teach visitors the Boasian insight of independent invention. Hence, there is nothing to prevent Visitor B from attributing a causal connection between the artifacts in one gallery with those in another, based solely on similarity of physical traits. Nor do the culture-specific gallery divisions provide opportunities to explore theoretical debates in the anthropology of art, such as the relationship between mediums and motifs.

Reflections

19 Insofar as the exhibit follows the recommendations of the joint Canadian Museums Association and Assembly of First Nations Task Force Report (Nicks and Hill 1992), and responds to various other First Nations voices and criteria, it is a thoroughly successful materialization of the curatorial team’s transforming visions. The goal of the new vision is to help level the power imbalance and improve relations between Native and non-Native peoples by working together to represent First Peoples in new ways. This entails an underlying premise that representation (i.e., public education) effects social transformation. Therefore, the “success” of the exhibit should technically be measured by its educational effectiveness. This cannot be validly measured, however, based on information gleaned from random visitors at the members’ preview, with the exhibit itself in an unfinished state. Nevertheless, this evidence does suggest that curators face significant challenges to realizing their educational goals due to financial limitations, administrative authority over design decisions and because of the various interpretive frameworks that visitors bring with them to anthropology galleries.

20 Although seemingly self-evident, it is noteworthy that curators can be most effective in those areas in which they exert the most control. Leaving aside issues of finance and authority for the moment, the visitors’ interpretive framework that presents the least challenge to overcome is the haunting memory of the ethnographic present. The new First Peoples gallery will be successful in this precisely because it is the curators’ deliberate intention to do so. In that this theoretical concept underlies the culture area approach to interpretation and display, it is at the very center of the paradigmatic shift that this exhibit promotes.

21 The culture area concept arose in the first half of the 20th century as a simplistic tool that anthropologists used to develop typologies of random cultural traits for the convenient classification of ethnographic data (Steward 1955: 78-82). By the mid-20th century, however, the diagnostic traits that defined culture area classifications incorporated cultural ecology, a theoretical approach in which cultural traits resulted from human interaction with environmental conditions (Murphy 1977: 21-23). Current anthropological theory acknowledges the influences of environment, but also recognizes those of historical factors such as migration, trade and alliance in the establishment, maintenance, negotiation and transformation of cultural traits. Moreover, aboriginal critiques of the culture area concept were particularly scathing (Young Man 1990: 71). Cree artist/curator Gerald McMaster presents an alternative approach that he calls “our interrelated history” (2002: 3). He points out that Natives and non-Natives have shared a common history in North America for the past few hundred years. In order to desegregate Native art so that it can assume its rightful centrality to Canadian heritage and national identity, he advocates museum exhibits that either include the artistic traditions of both groups, or demonstrate the “dialogical relation of the objects.” For example, he applauds recent scholarship that focuses on tourist arts and museum exhibits that “touch on the idea of interrelationship” (5-6).

22 The ROM’s First Peoples gallery includes numerous elements that are designed specifically to dislodge the preconceptions of the ethnographic present promoted by the culture area approach and replace them with new visions of our interrelated histories. We observed this effect with the portrait of Evelyn Johnson which, given a label, may have inspired a transformative moment for a visitor. Even if this single instance did not, the repetition of such encounters throughout the exhibit will likely produce the desired effect on most visitors. In order for the educational message to be thoroughly successful, however, it must not only disprove previous assumptions, but it must also fill the gap left by this decentreing with an engagement with the new storyline. This effect was evident by the interest visitors took in learning about the artifacts, their repeated complaints about the missing labels and their questions about specific pieces. For these reasons, I believe the vision of the new First Peoples gallery has great potential to induct the public into the principles of the new paradigm.

23 Once the broad outlines of the paradigmatic shift have been accomplished, however, I think museum anthropologists should continue to refine the educational messages of exhibits of First Peoples artifacts. Reflections on the visitors’ comments at the ROM’s members’ preview suggest several issues bear consideration. Besides the ethnographic present discussed above, these comments pointed to three additional interpretive frameworks that will benefit from further reflection: childhood memories of particular past exhibits, other galleries in the same museum and displays from other museums. Issues arising from the effects of these frameworks suggest that museum anthropologists must exercise caution in their enthusiasm to amend errors of the past so that they do not eliminate the good with the bad. Instead, I suggest that certain aspects of the interpretive strategies of both the evolutionary and culture area paradigms may be adapted to the service of the new paradigm.

24 The most important lesson to be learned from the apparent influence of childhood memories of particular exhibits is that the interpretive strategies of the culture area paradigm, particularly the dioramas, were effective instruments for impressing juvenile audiences. I am not suggesting that dioramas should be retained—especially since they are too permanent and too expensive to justify in an intellectual climate of partial, multiple and historically contingent truths. I have pointed out, however, that many Native owned and operated museums have chosen to employ them. More important than the specific method chosen, the power of childhood impressions of museum exhibits should not be overlooked in developing interpretive strategies for the new paradigm. Although undeniably intellectually sophisticated and complex, one of the tasks of museum anthropology should be to distill this complexity into a potent form for mass consumption, especially for the impressionable years of learning. As pointed out above, this aim could be accomplished through the strategic use of open storage, if institutional administrators could be persuaded of the need to fund this component.

25 The main issue raised by visitors’ interpretive frameworks within multiple galleries in the same museum is the need to develop interpretive strategies for questions in comparative anthropology. This is important because a public more familiar with anthropological theory and methods is better equipped to understand the lessons associated with any specific historic/cultural context. Because comparative anthropology deals directly with questions of concern to the discipline, it is ideally suited to this educational objective. For the same reason, however, problems with the way it was practised in past paradigms have made it to some extent inimical to the new museum anthropology/art history, which insists on the specificity of time, place and peoples. In fact, comparative museum displays were virtually abandoned with the advent of the culture area paradigm.

26 As Brian Durrans pointed out almost two decades ago, museum anthropology’s unfortunate abandonment of comparative displays accompanied its separation from, and subordination to, academic anthropology (1988: 163). Both of these developments can be linked to Boas’s influence on American anthropology. Indeed, Jacknis (1985: 103-05) documents the process through which Boas’s museum practice gradually shifted focus from artifacts to monographs so that ultimately his exhibit labels developed into monographs. He would not complete his installations until the monographs were written. This process ran parallel to Boas’ introduction of the concept of cultural relativism upon which the culture area paradigm rests. This initiated the relativistic trajectory that academic anthropology has been following until recently—a path wherein each culture is treated only in terms of its own “unique” inner holism (Durrans 1988: 163). Perhaps for this reason, although Boas finally synthesized and recorded insights he derived from comparative studies of artifacts in Primitive Art (1927 [1955]), very few comparative studies of artifacts were undertaken before Richard Anderson’s Art in Primitive Societies (1979), later revised as Art in Small Scale Societies (1989). Now that museum scholarship has matured, perhaps curators can take a leading role in demonstrating the unique contribution that their discipline can make to academic anthropology through comparative artifact studies.

27 The development of temporary exhibits devoted to comparative questions—on themes such as processes of culture change, the relationships between motifs and mediums and those between environment, economy and technology—could simultaneously demonstrate the heuristic value of comparative museum anthropology within the discipline of anthropology, across the disciplines with which museum anthropologists interact and to the general public. One of the educational roles of such exhibits would be to augment understanding of the culture-specific displays in permanent galleries. Comparative questions, however, may also be introduced within culture-specific permanent galleries. As highlighted by Visitor D’s comments, the new First Peoples gallery moves in this direction in the section dealing with contemporary art by showing processes of culture change. As we move forward in the 21st century, I believe much more may be accomplished if we bring our increased analytic sophistication to bear on comparative exhibits.

28 Consideration of the final interpretive framework arising from visitors’ comments—their experiences in other museums—brings us face to face with variables over which museum curators have the least control. In particular, we are reminded of two interrelated issues: the relative obscurity and low public profile of museum anthropology within the museum profession (combined with particularly acute financial constraints in a period of general fiscal crisis) tends to promote competition among museums; at the same time, the low profile and financial constraints pose challenges to the realization of exhibit plans, perpetuating the cycle of professional and public obscurity and misunderstanding. With regard to the first issue, anthropology museums, and/or displays within other types of museums, must compete not only with established genres such as fine art and history museums, but also with a new outcropping of specialized museums. Insofar as all of these types of museums seek to increase the numbers of their visitors to offset financial shortages, they are under great pressure to please the public, which is accustomed to high-tech entertainment on demand today more than ever before.6 Thus we arrive at the second issue. As we have seen in the case of the audio interpretation devices and open storage, such cutting-edge interpretive strategies are not always financially possible for anthropology exhibits, and this may detract from the effectiveness of such exhibits for some visitors.

29 In order to overcome challenges arising from the obscure place of museum anthropology among museums in general, I think museum anthropologists should employ a two-pronged approach. First, within the budgetary and administrative limitations of given exhibit plans, curators should strive to satisfy public expectations by meeting them halfway with a judicious balance of the known and the unknown; of the spectacular and the common; and of the simple and the complex. This would ensure that “hooks” are built into the content of the exhibit without having to resort to high tech interpretive aids to gain the audience’s attention and maintain their interest. Secondly, outside the context of exhibits, museum anthropologists should strive to raise the profile of the discipline through presentation of research and other professional activities in scholarly and public venues.

Conclusion

30 The Royal Ontario Museum’s new Gallery of Canada: First Peoples embodies the transforming visions of both the modernization theme of Renaissance ROM, and the paradigm shift of the new museum anthropology/art history. It was through the agency of the former that the gallery was conceived and brought to fruition. Renaissance ROM has given the gallery a prominent place on the rotunda opposite the Gallery of Canada: Historical and Decorative Arts. Yet, the ROM administration’s central authority over design decisions and financial priorities acted as a serious limitation to the intellectual and socio-political imperatives of the latter. Perhaps the shift away from the Queen’s Park entrance, around which the two “Canada” galleries are oriented, towards the new Bloor Street entrance of Libeskind’s crystal is symbolic of a reorientation away from the academic focus of the University of Toronto buildings on Queen’s Park toward the commercial focus represented by the upscale Bloor Street business district.

31 Nevertheless, the curatorial team and Native collaborators produced an exhibit that exemplifies the principles of the new paradigm and promises to transform public perspectives regarding Canada’s First Peoples and, perhaps more importantly, non-Natives’ relationships with them, both past and present. As one of few major anthropology museum venues in Canada, the Royal Ontario Museum is thus poised to lead the way into the new era of revitalization in Canadian museum anthropology. I believe, however, that there is yet much urgently needed work to be done to refine and expand the interpretive messages and strategies of the new museum anthropology/art history. Likely, our greatest challenge will be to find ways to overcome financial shortages and administrative interventions that hinder this work. In this regard, we may be wise to recover some of the strengths of previous paradigms and adapt them to the new.

References

Anderson, Richard L. 1979. Art in Primitive Societies. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

———. 1989. Art in Small Scale Societies. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Boas, Franz. 1920 [2000]. The Methods of Ethnology. In Anthropological Theory: An Introductory History, eds. R. Jon McGee and Richard L. Warms, 134-41. Mountain View, CA: Mayfield Publishing.

———. 1955. Primitive Art. New York: Dover Publishing. (Orig. pub. 1927.)

Chapman, William Ryan. 1985. Arranging Ethnology: A. H. L. F. Pitt Rivers and the Typological Tradition. In Objects and Others: Essays on Museums and Material Culture, ed. George W. Stocking, 15-48. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press.

Doxtator, Deborah. 1996. The Implications of Canadian Nationalism for Aboriginal Cultural Autonomy. In Curatorship: Indigenous Perspectives in Post-Colonial Societies, Proceedings, eds. Joy Davis, Martin Segger and Lois Irvine, 56-76. Ottawa: Canadian Museum of Civilization.

Durrans, Brian. 1988. The Future of the Other: Changing Cultures on Display in Ethnographic Museums. In The Museum Time Machine: Putting Cultures on Display, ed. Robert Lumley, 144-69. London: Routledge.

Hedlund, Ann Lane. 1994. Speaking For or About Others? Evolving Ethnological Perspectives. Museum Anthropology 18(3): 32-43.

Hinsley, Curtis. 1981. The Smithsonian and the American Indian: Making a Moral Anthropology in Victorian America. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Jacknis, Ira. 1985. Franz Boas and Exhibits: On the Limitations of the Museum Method of Anthropology. In Objects and Others: Essays on Museums and Material Culture, ed. George W. Stocking, 75-111. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press.

Landes, Ruth. 1938. The Ojibwa Woman. New York: Columbia University Press.

McMaster, Gerald. 2002. Our (Inter)Related History. In On Aboriginal Representation in the Gallery, eds. Lynda Jessup and Shannon Bagg, 3-8. Ottawa: Canadian Museum of Civilization (Mercury Series Paper 135).

Murphy, Robert F. 1977. Introduction: The Anthropological Theories of Julian H. Steward. In Evolution and Ecology: Essays on Social Transformation by Julian H. Steward, eds. Jane C. Steward and Robert F. Murphy, 1-39. Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Nicks, Trudy and Tom Hill, eds. 1992. Turning the Page: Forging New Partnerships between Museums and First Peoples. Ottawa: Canadian Museums Association and Assembly of First Nations Task Force on Museums and First Peoples.

Phillips, Ruth B. 2002. A Proper Place for Art or the Proper Arts of Place?: Native North American Objects and the Hierarchies of Art, Craft and Souvenir. In On Aboriginal Representation in the Gallery, eds. Lynda Jessup and Shannon Bagg, 45-72. Ottawa: Canadian Museum of Civilization (Mercury Series Paper 135).

Steward, Julian H. 1955. Theory of Culture Change: The Methodology of Multilinear Evolution. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Vastokas, Joan. 1987. Native Art as Art History: Meaning and Time from Unwritten Sources. Journal of Canadian Studies 21(4): 7-36.

Young Man, Alfred. 1990. Review of The Spirit Sings: Artistic Traditions of Canada’s First Peoples (museum exhibit). Toronto: McClelland and Stewart. American Indian Quarterly 14(4): 71-73.

Notes