Design, Presentation Silver and Louis-Victor Fréret (1801-1879) in London and Montreal

Ross FoxUniversity of Toronto

Résumé

Fréret fut l’un des dessinateurs/sculpteurs français actifs en Angleterre au début de l’ère victorienne qui contribuèrent au progrès du design britanniques, surtout dans les domaines de l’orfèvrerie et de la céramique. Les chercheurs de notre époque ont complètement méconnu ces créateurs. Le but de cette étude est de restituer la vie et l’œuvre de Fréret qui travailla pendant les années 1840 et 1850 comme dessinateur et sculpteur de pièces honorifiques pour les fabricants distingués de Londres, Mortimer & Hunt, Hancock, et Edward Barnard & Sons. Les archives de la compagnie Edward Barnard & Sons qui se trouvent au Victoria and Albert Museum ont été des documents fondamentaux pour cette recherche. En dehors de l’analyse des ouvrages les plus importants, cette étude vise à considérer le succès obtenu par Fréret en regard des conditions artistiques et des influences de son époque. Je présenterai dans la conclusion de cet article l’activité de Fréret à Montréal, ainsi que quatre surtouts de table en argent qui lui sont attribués et qu’il dessina pour l’orfèvre Robert Hendery. Ces pièces d’orfèvrerie montrent la diffusion de concepts du design anglais par les artisans immigrés ainsi que leur adaptation aux besoins des clients canadiens.Abstract

Fréret was one of many French sculptor-designers working in England during the early Victorian era who contributed to the advancement of British industrial design, particularly in silver and ceramics. None of these designers, however, has received his due from modern scholarship. This study provides a partial reconstruction of the career of Fréret, who worked during the 1840s and 1850s as a designer and modeller of presentation pieces for the distinguished London silver manufacturers, Mortimer & Hunt, Hancock and Edward Barnard & Sons. The Barnard daybooks at the Victoria and Albert Museum were a prime source. Besides analyzing highlight pieces, this study examines Fréret’s achievement against the background of the artistic conditions and influences of the time. It concludes with Fréret’s activity in Montreal and the attribution of four epergnes designed by him for the silversmith, Robert Hendery. These pieces demonstrate the dissemination to Canada from England of design concepts through an immigrant craftsman, and their modification to suit the special requirements of Canadian customers.1 Historically the British had an infatuation with what was perceived as French artistic superiority. At no time was this impulse stronger than during the decades of the mid-19th century, which witnessed an influx of French émigré artists and designers into Britain. Many slipped into the anonymity of an industrial culture where recognition was afforded only a few and, more often than not, employers vicariously appropriated credit for their artistic achievements. Such conditions render the modern-day study of these artists difficult. This article attempts a reconstructive assessment, albeit checkered, of the achievement of such a person in the silver industry. As a trained sculptor, Louis-Victor Fréret was engaged in the modelling and designing of silver for leading London-based manufacturing silversmiths—Mortimer & Hunt, Hancock and Edward Barnard & Sons. The body of work that is attributable to Fréret consists largely of presentation pieces that were acclaimed in their own time. The design character of most is French, although supporting English themes, while others reflect a cultural accommodation, and still others are thoroughly English in concept and execution.

2 Then in 1862, for reasons that are unclear, Fréret left London for Montreal, Canada, where he entered the employ of the manufacturing silversmith, Robert Hendery and became responsible for the first-ever Canadian presentation centrepieces. As in Britain, Fréret adapted to local conditions. That same decade saw the gestation and birth of the nation of Canada, when symbols of identity were being formulated in order to articulate a sense of cultural uniqueness in a former colony where pan-Britannic sentiments and nostalgia for the earlier French ascendancy coexisted and often collided. Only four Canadian presentation pieces can presently be ascribed to Fréret, but all are replete with new emblems. They represent a special effort to “Canadianize” silver design. Otherwise, they differ little from British productions. Fréret’s place in the history of Canadian silver is as a pivotal agent in the transmission of fashionable design in silver from the Old World to the New, not merely mimetically, but through his influence as a sculptor, modeller and designer who actually went abroad.

3 An indirect measure of Fréret’s overall achievement in silver design is captured in a succinct appreciation of the silverwork of the 19th century written by John Pollen in 1878: “The most noticeable objects executed during this century are probably the vases and groups of figures called race cups” (cxciii). This estimation applies equally well to silver testimonials which, together with trophies, are known by the generic terms of presentation pieces or honorific silver. Fréret succeeded in creating a legacy of presentation pieces, both in Britain and Canada, which are of considerable merit.

The State of Studies of Presentation Silver

4 Since the 1960s, with the scholarly rehabilitation of Victorian period silver, there has been a renewed appreciation of presentation silver as representing a measure of the superlative attainment of 19th-century design. Patricia Wardle was the first to broach the subject of presentation silver seriously with her 1963 book, Victorian Silver and Silver Plate. John Culme’s Nineteenth-Century Silver followed in 1977. While the focus of both was on English silver, Culme extended the investigation of design influences. The parameters of studies expanded internationally in 1985 with the National Gallery of Canada’s book, Presentation Pieces and Trophies from the Henry Birks Collection of Canadian Silver, by Ross Fox; and in 1987 with Houston’s Museum of Fine Arts exhibition catalogue, Marks of Achievement: Four Centuries of American Presentation by David B. Warren et al. Then, in 1999, Roger Perkins covered the narrow topic of English military and naval silver. An article written by Angus Patterson for the 2001 issue of the Journal of the Decorative Arts Society also provided a useful overview of more outstanding English presentation silver. Not to be omitted is 19th Century Australian Silver by John Hawkins (1990), which gave considerable coverage to presentation silver and provides a good counterpoint of comparison with Canada.

French Designers in England at mid-19th Century

5 A spirit of homage to French authority in aesthetics and design had existed in Great Britain since the 18th century. It peaked from the 1830s through the 1860s, when it provided a paradigmatic source for the stylistic character of so much of the decorative and applied arts in Britain.1 But English art critics were not agreed as to the salubrity of French influence on English design. In 1871, George Wallis—a keeper at the South Kensington Museum—gave this reproachful assessment:Greatly misled by the prevailing tendency to test all designs, especially industrial design, by a French standard, which had grown up so largely during the period that had elapsed since 1830, from the growing intercourse of the two countries, the English manufacturer almost repudiated everything like originality. (6)Formal recognition of French superiority in design knelled loudly on the international stage in 1851 at the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations. Manufactured goods from around the world were assembled there for the first time for unmediated comparison. Above all, it was a visceral national competition between Great Britain and France (Bury 2000: 162). Not surprisingly, for an adjudication process that was not untainted by bias, the host country took the lion’s share of medals; but France ranked second. The strengths and weaknesses of the two countries were vividly apparent. It was widely conceded that the British were the leaders in mechanized production and the mass output of consumer goods on an industrial scale that were mediocre in quality, if lower priced. The French were the leaders in the area of expensive luxury goods, where high quality and refinement in materials, craftsmanship and design were requisite; these goods were largely handmade by skilled workers in small establishments (Walton 1992: 14-15, 118-19, 206-07).

6 The grip of French design on English manufacturers would take decades to loosen, in part because it was endorsed by the British art educational system. Of the metalwork objects that were purchased from the Great Exhibition for the embryonic Museum of Manufactures (later the Victoria & Albert Museum) that opened the following year in conjunction with the London School of Design, a “considerable proportion” was “the production of the most eminent French gold and silver smiths, and exhibit[ed] either a very high order of excellence in design and workmanship, or some peculiarity in the processes by which they have been produced” (Times,19 May 1852).2 They included twenty-three pieces of French metalwork, versus twenty-two English. The avowed mission of this museum was to inspire young artists to better what was regarded as the best design and craftsmanship in the area of manufactures (Wainwright and Gere 2002: 11-19).

7 French influence in design asserted itself in England with particular efficacy through the intermedium of émigré artists. They included many “fine-art” sculptors who worked as designers and modellers in the industrial sector, particularly in ceramics and silver. This crossover of fine art with the decorative and applied arts had a long history in France, whereas in England the art establishment observed a more rigid distinction between artist and artisan. As a result, few outstanding English artists were attracted to industrial design. William Dyce outlined the advantages of the French design process in a report on European schools of design written in 1840:There is no circumstance in France connected with the application of design ... that deserves more special notice than the high estimation in which industrial artists are held, and the free and unrestrained exercise of their judgment and taste which is consequently allowed to them ... You may employ him or not as you think fit, but having given him a commission, it is he, not you, who is responsible for the merits of his performance ... his taste and judgment must be equally allowed to control the manner and process of reproduction.3In British practice, a designer merely supplied patterns and, in general, was not part of the production process. British manufacturers rightly came to fear that a reputation for mediocre design exposed them to a potential loss of market share to the French. To improve standards, they often welcomed French artists, who were not only more pragmatic in their working methods, but also more versatile in their skills (Morris 2005: 248-49, 251). There was a particularly large influx of these Frenchmen during the late 1840s and 50s. One such craftsman was Pierre-Emile Jeannest who went to London circa 1845-46 and joined Minton as a designer and modeller several years later; in 1853, he transferred to Elkington & Co. where he became head of design (Jones 1981: 124; Atterbury and Batkin 1998: 276). Others went to England in the aftermath of the French Revolution of 1848. They came both for economic and political reasons. Among them were court artists such as the sculptor, Carlo Marochetti, who followed Louis-Philippe into exile. He became a longstanding favourite of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, to the dismay of the highly xenophobic English art establishment. Léon Arnoux also arrived in 1848, joining Minton the next year as art director (Ward-Jackson 1985: 147n2).

8 Some of the French sculptor-designers who worked for the English silver industry over the next decade were: Jean-Valentin Morel, Antoine Vechte, Elisabeth-Eloise Vechte, Auguste-Adolphe Willms and Henri-Auguste Fourdinois, who emigrated in 1849; Hugues Protât in 1850; Louis Fechter by 1851 and Léonard Morel-Ladeuil in 1859 (Morris 2005: 248-51; Hargrove 1976: 185-95). Most were multi-skilled ornamental sculptors; others such as Morel and the Vechtes were also expert workers (i.e., chasers) in precious metals. Antoine Vechte, acclaimed both in England and France as the “greatest living worker in silver” (Times, 4 September 1867), introduced into England the art of virtuoso, Renaissance Revival repoussé work.

9 As late as 1874, John Sparkes, art master of the Lambeth School of Art and afterwards principal of the National Art Training School at South Kensington, lamented the dependence of British manufacturers on French artists. According to his assessment, it resulted from a failure of the art education system: “Still we find French modellers giving the work of the largest Staffordshire potters an European fame; French modellers making the works of our great silversmiths and electrotypists” (Walford 1878: 424; Werner 1989: 14). It was this English predisposition for French design and designers during the early Victorian period that accounted for much of Fréret’s success in London.

Louis-Victor Fréret

10 Born in 1801, Louis-Victor Fréret belonged to a dynasty of well-known artists in Cherbourg, France. His father (François-Armand) and paternal grandfather (Pierre) were sculptors, while his son, Armand-Auguste, became a successful marine painter. From 1820 until 1822, Louis-Victor studied carving (sculpture) at the École royale d’arts et métiers de Châlons-sur-Saône and afterwards under Joseph-Louis Hubac (1776-1830), at the naval dockyard in Toulon. By 1825, he was back in Cherbourg working as a sculptor for the naval dockyard, where his father, by then deceased, had been chief sculptor. That same year Louis-Victor carved the decoration for the corvette Cornélie. Over the next decade he did similar work for a number of warships. Like his father and grandfather before him, he also produced sculpture for Catholic churches in the area, including a statue in wood entitled Education of the Virgin for the Church of Sainte-Trinité in Cherbourg (La Presse de la Manche, 22 April 1990).

Fréret as a Silver Designer and Modeller in England

11 The 1841 census of England recorded Fréret as living in the civil parish of St. Mary Islington East, a burgeoning middle-class residential district just north of London. His occupation was given as sculptor. Fréret’s oldest child, four-year old Éloïse, was born in England, suggesting that Fréret had established himself in the country by 1837 at the latest.

12 In 1841, Fréret was in the employ of Mortimer & Hunt, successor to Storr & Mortimer, the illustrious manufacturing and retail jewellers and silversmiths whose reputation was rivalled only by Rundell, Bridge and Rundell (and its successor R. and S. Garrard & Co.), as purveyors of jewellery and silver plate to British and European royalty and upper classes. That year, Fréret, together with Hamilton MacCarthy and Edward Hodges Baily, also of Mortimer & Hunt, created a trophy—the Queen’s Vase—that would be awarded to the winner of the 1841 Queen’s Vase horse race. Baily was the designer in charge “to whose judgment and suggestions much of the elegance and purity of the composition is to be attributed” according to the Times (7 June 1841). First sponsored by Queen Victoria, the Queen’s Vase is a flat horse race for three-year-old thoroughbreds. It is run over a distance of two miles at Ascot Racecourse in England, on the first day of Royal Ascot Week—a major event on the British social calendar.

13 The Queen’s Vase for 1841 was not a vase or cup as such, but a small-scale sculpture or statuette in silver. Silver sculpture was a relatively new category of presentation silver (which itself was growing in popularity and increasingly yielding grandiose, if not surcharged, pieces). Before long, silver sculpture began to replace more traditional standing cups, urns or allied tableware forms for esteemed trophies or honorific pieces. Silver appeared most frequently as horse racing trophies in conjunction with the Ascot, Goodwood and Doncaster horse racing meetings (Wardle 1963: 125). Pieces such as the Queen’s Vase for 1841 required a considerable investment that often did not provide a monetary profit for the producer. Manufacturers often looked upon them, however, as an opportunity to showcase their technical capabilities and promote their reputations, while their profits were made with more modest wares.

14 As with a great many horse racing trophies, the Queen’s Vase for 1841 incorporated representations of horses: the subject was the youthful Alexander the Great encountering the wild-spirited, but magnificent white stallion, Bucephalus, which became his great war horse. The Times (7 June 1841) described the piece:It is a group representing Alexander the Great about to mount the back of the untamed Bucephalus. The Macedonian hero is beautifully modelled. He is just such a person as historians, poets, and sculptors, have represented him—the beau ideal of a Greek portrait. The horse is very fine, full of fire, having the peculiar formation of the head ascribed to the original, and exhibiting the blood of the barb, or oriental horse, with the bone and muscle of the heroic horse.The theme was derived from classical history, the most elevated thematic category promulgated by European art academies. In this case, the literary source is an ancient Greek legend as recounted by Plutarch (257-58). Through an amalgamation of classical subject matter and sculpture, the concept of the trophy was elevated from the mundane level of a memorial cup to that of fine art. It signified a desire to invest the Queen’s Vase with an imposing hierarchical symbolism worthy of the royal station of the trophy’s donor and the great annual social and sporting event it celebrated—over which the Queen and Prince Albert, in fact, presided. Just as the mythic incident illustrated in the Queen’s Vase was interpreted as a portent of Alexander’s future greatness, it served equally well as a felicitous metaphor for the young Queen Victoria and the promise of a glorious reign, Britain’s expanding imperial hegemony, horse races as a sport of monarchs and Victoria’s personal love for horses and horsemanship. Heroism was the message in synoptic terms and certainly this noblest of virtues was conveyed more eloquently in figural sculpture, than through a matter-of-fact dedication inscribed on a loving cup.

Fig. 1 The Goodwood Cup (Robin Hood Contending for the Golden Arrow), Illustrated London News, Aug. 3, 1850, p. 97. Photo by Brian Boyle, Royal Ontario Museum.

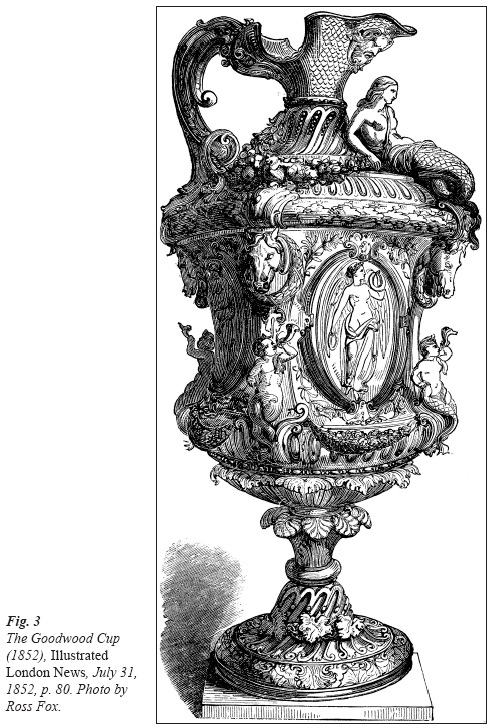

Display large image of Figure 1

15 Fréret modelled Alexander, MacCarthy the horse, of the 1841 Queen’s Vase. This was not their last collaborative work. The two partnered as modellers on other honorific silver projects with Fréret doing the figuration and MacCarthy serving as animalier (Gunnis 1968: 247-48). It would be 1850, however, before Fréret again received noticeable public recognition for a presentation piece in a sculptural group.

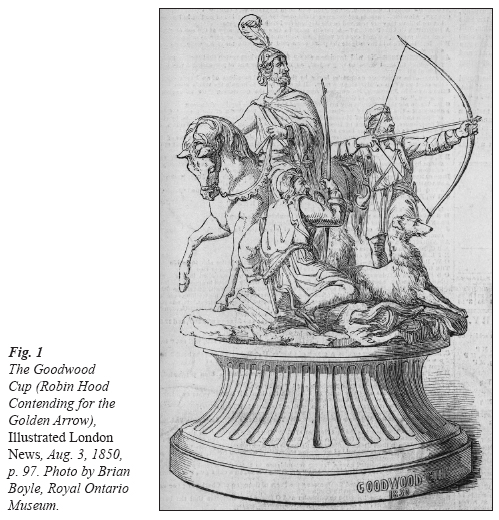

16 In January 1849, Charles Frederick Hancock retired as a partner in Hunt & Roskell to form a competing firm under his own name (Culme 1987: 1: 208-09). By August, he was granted a Royal Warrant of Appointment from Queen Victoria as a supplier to the royal family. This sponsorship enabled Hancock to claim many elite clients and to employ top-rank artist-designers and silver-workers including Henry Hugh Armstead, Marshall Wood, Raffaele Monti and Hamilton MacCarthy, who had moved from Hunt & Roskell to Hancock. Together again, Fréret and MacCarthy collaborated to produce the 1850 Goodwood Cup, a trophy that newspapers of the day recognized as an early masterwork of Charles Frederick Hancock’s new firm (Illustrated London News [ILN] (23 August 1850); Times (27 July 1850); Bell’s Life in London and Sporting Chronicle [Bell’s Life] (4 August 1850). Designed for another flat-racing event held annually at the end of July under the patronage of the Dukes of Richmond, the piece took the form of a sculptural group entitled Robin Hood Contending for the Golden Arrow (Fig. 1). MacCarthy modelled the horse, which an ILN (3 August 1850) reviewer referred to as “the largest ever formed in silver.” It was further noted that the design was after “the eminent French artist, M. Freret, who modeled a racing cup last season.”

17 The reviewer’s highlighting of Fréret as a French artist was by no means incidental but intended to endow the Goodwood trophy with overtones of enhanced prestige as an artwork. As exemplified in this piece, the contribution of French artists to English silver design was not necessarily limited to style and technique, but sometimes extended to the interpretative approach to thematics. Such is the case for the Goodwood Cup of 1850, however English it may otherwise appear. Depicting Robin Hood competing in an archery contest organized by the Sheriff of Nottingham, Robin Hood is shooting an arrow, while observed by Little John and the sheriff on horseback. Tales of Robin Hood and the golden arrow date at least as early as the 15th century with the ballad “A Gest of Robyn Hode” (Knight and Ohlgren 1997: 80-81). It was Sir Walter Scott, however, who revived and popularized this tale of Anglo-Saxon heroism in his novel Ivanhoe published in 1819.4 Whether based on an episode from actual history or on an historical novel, the bravura content resonates with robust patriotic overtones, reflecting British hubris in the age of empire.

18 The overt Englishness of the subject masks a French element in both its choice and rendition. Medievalizing sculptural groups such as this were derivative of the genre historique or historical genre thematic category in French painting, and to a lesser extent in sculpture, which matured during the early 19th century and was officially legitimized at the Paris Salon of 1833. Because of its medieval character, it is also known as the style troubadour. It represented a new, but inferior category of subject matter that broke with the doctrinaire approach to historical subjects of the academies of art, which advocated subjects from ancient Greek and Roman history and mythology, as well as Christian teaching. The style troubadour focused on anecdotal, genre-like episodes that were often nationalistic and legendary in character, and based on more recent literature. The romantic medievalizing writings of Sir Walter Scott were a powerful inspirational source in France as well as England. Bell’s Life (2 August 1840) reported that one of the earlier Scott themes in silver sculpture, based on the poem Marmion, occurred with the Stewards’ Cup for the 1840 Goodwood meeting.

19 In the style troubadour, there was a more humanized aspect to history. It was more emotionally, if not intellectually, accessible—often portraying famous persons in everyday circumstances where there is a sense of temporality, rather than performing time-arresting acts of boundless heroism and profound moral significance, as in traditional history painting. There is also a sense of antiquarian authenticity in the definition of setting and costume (Wright 1997: 31-47). Silver sculptures like the Robin Hood Contending for the Golden Arrow contain reminiscences of the work of the French bronzeur, Jean-François-Théodore Gechter, among others. The acme of popularity for silver sculpture in Britain was during the 1840s, although it was still seen into the 1850s and beyond (Schiff 1984; Duro 2005).

20 Fréret’s 1850 Goodwood Cup was displayed in Hancock’s exhibit at the Great Exhibition of 1851. The silver sculpture, The Entry of Queen Elizabeth on Horseback into Kenilworth Castle—also in the style troubadour—was part of the exhibit, as well. In the literature about the exhibition, much consideration was devoted to the latter, while the former received scant attention. Fréret’s name was even omitted from the exhibition’s official catalogue (Ellis 1851, vol. 2:692). Admittedly, the Queen Elizabeth group was a showpiece made especially for the Great Exhibition; additionally, it had the extra cachet of being the work of the highly praised Baron Marochetti, whose name was noted.

Fig. 2 Wedding Gift of Crown Prince Karl Ludvig Eugen of Sweden to Princess Louisa of The Netherlands, Illustrated London News, Nov. 23, 1850, p. 404. Photo by Ross Fox.

Display large image of Figure 2

21 As George Wallis explained in a government report on the London International Exposition of 1862: “British manufacturers are not accustomed to declare the sources from which they obtain designs ... whilst any public recognition of the ability of their workmen, as such, is a novelty.”5 Auguste Willms (1890), art director at Elkington & Co., who had first-hand experience in both the French and British systems, was more explicit in his criticism. A designer entered a workshop in Francewith the knowledge that he will enjoy to the full the reward due to his own merit. His work will bear his name, and no man dare steal his ideas. The manufacturer does not seek to enhance his own reputation by stifling that of his employés.... In England, except in the cases of a few illustrious firms ... the designer works unknown.... The writer is acquainted with a case in which an artist’s work gained no fewer than five high awards, some of them gold medals, for the firm which paid his wages, while he himself was not so much as favoured with an honourable mention ... another artist was discharged from the service of the same firm for having, in a public print, acknowledged the execution of works for which his employers were claiming all the credit. (5)With credit usually limited to the manufacturer, identification of the work of someone like Fréret is difficult, particularly when surviving primary documentation is relatively scarce. There are, however, a few exceptions in popular publications such as the Illustrated London News.

Fig. 3 The Goodwood Cup (1852), Illustrated London News, July 31, 1852, p. 80. Photo by Ross Fox.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 4

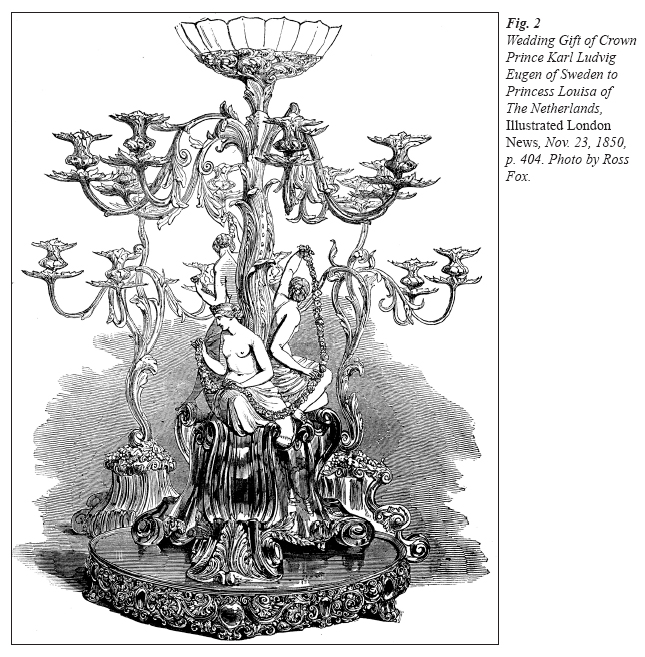

22 A November 23, 1850, article in that newspaper specified Fréret as the designer and modeller of silver candelabra commissioned from Hancock by Crown Prince Karl Ludvig Eugen of Sweden, in celebration of his marriage to Princess Louisa of The Netherlands (Fig. 2). Weighing approximately twenty-eight kilograms, the items actually consisted of an epergne-candelabrum on a mirror plateau en suite with two matching candelabra. The epergne conformed to a conventional type, combining sculpture with fixtures for candles and/or small bowls supported on branches and crowned by a large bowl. A shaped tripartite base functioned as a pedestal for small-scale statuary. The stylistic references were 18th century French, but in an updated Rococo Revival style that recalled Jean-Jacques Feuchère, who was in the vanguard of French decorative and applied sculpture of the Romantic Movement (Bouilhet 1908-12, 2:186-96). French revival styles were highly popular in England from the 1820s through the 1880s.

23 In 1852, another Goodwood Cup (Fig. 3) was featured in the Illustrated London News (31 July 1852). Also from Hancock, the design was supplied by the celebrated French painter, Eugène Lami, who resided in England from 1848 until 1852; Fréret was the modeller. In this instance the prize cup was a large, highly sculptural ewer in the so-called Louis XIV or Old French style, contemporary appellatives that were misleadingly applied to both the Rococo and Louis XIV styles. With its exaggerated ornamentation, this particular piece belonged more correctly to the Baroque Revival or contemporary French Second Empire style. As ILN described it:The vase has four panels, in which are figures in high relief of Victory, holding wreaths of laurel, the emblems of the deities and the reward of the victors.... Above the panels project in bold relief, from four niches, horses’ heads ... on the lower part of the body of the vase are Tritons, with wreaths of flowers, &c.; whilst from the upper part a finely-modelled statuette of the Ocean Venus is reclining. The vase is richly embellished with massive garlands of flowers, effectively arranged upon a varied ground of classical scrolls and devices in great variety of relief, of matted and polished silver.... On the outside of the lip is a mesh in polished silver with scales, and on the foot a wreath of vines gives variety of effect and richness to the whole work.This was one of four prize cups for the 1852 Goodwood meeting, three by French designers—Lami, Antoine Vechte and an unidentified third person. Vechte, like Lami, reverted to a vessel type in his trophy, as opposed to pure sculpture; in Vechte’s case, it was a two-handled vase-like receptacle reminiscent of an ancient Greek amphora. The surface of Vechte’s piece was intertwined with nude and semi-nude classical figures in relief depicting scenes from the wedding feast of Pirithous, including the Centauromachy. Vechte’s vase exemplified the Renaissance Revival. The Lami-Fréret trophy was conceived similarly, but from a Baroque standpoint. French emigrant artists such as Vechte, Lami and Fréret, launched a new direction in English honorific silver, away from pure sculpture in favour of a compromise approach of vessels treated sculpturally (Schroder 1988: 276). A Times (28 July 1852) editorialist commented on these Goodwood cups: “These three cups, all the works of foreigners, will, it is hoped, excite the emulation of English artists, and give an increased momentum to the pursuit of perfection in art.”

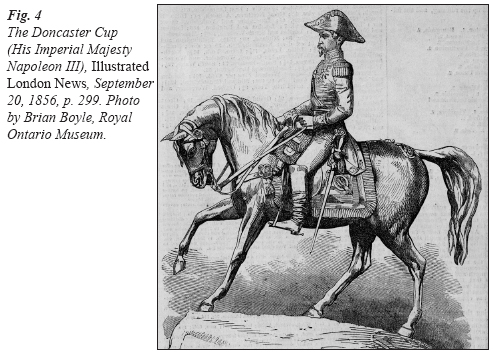

24 Fréret also contributed to two silver statuettes that Hancock exhibited at the Paris Exposition Universelle of 1855 (ILN, 15 September 1855). One represented Napoleon I crossing the Alps; the other Napoleon III on horseback (Fig. 4). Eugène Lami designed the first; Fréret the second. In both cases, Fréret modelled the figures and Hamilton MacCarthy the horses. In 1856, the statuette of Napoleon III became the Doncaster Cup, also a horseracing prize (ILN, 20 September 1856).

25 By mid-1853, Fréret was employed by the firm of Edward Barnard & Sons, the largest silver manufacturer in England (rivalled only by Elkington and Co. in the quantity of presentation pieces produced). Most were commissioned by retail silversmiths, but Barnard also furnished presentation silver, as well as other silver wares, to manufacturing silversmiths such as Hancock, Elkington & Co., Hunt & Roskell, R. & S. Garrard & Co., A. B. Savory & Sons, to name a few. Because these customers/retail silversmiths usually took credit for the workmanship themselves, Barnard’s true place in the history of English silver is probably the least understood of all major silver manufacturers. Barnard’s factory ledgers or daybooks provide some insight as to Fréret’s activity for that firm, but not all entries record a designer and/or modeller, and thus do not give a precise measure of Fréret’s work for Barnard.6 Fréret’s name was found in conjunction with twenty-four entries in the period from August 1853 to December 1864, which included the following pieces: one epergne,7 four epergne-candelabra, nine centrepieces, one candelabrum, one rose water dish, two vases, a set of four salts, one statuette, two ewers, two pedestals (for ewers), two covered cups and one plateau.8 One centrepiece was electroplate. Apparently almost all, except for the salts and possibly an ewer and pedestal, were presentation pieces. In addition, it can be deduced from cross-references provided within some entries that Fréret models were used for another five pieces. Fréret’s name was given as modeller in fifteen entries, as designer in five; for the remainder his role, whether as modeller or designer, was ambiguous—to confuse matters, sometimes the term modeller was interchangeable with designer. In only three instances where Fréret was modeller is another person named as designer: in two cases it was Charles Philip Slocombe, in the third, Thomas Reeves.

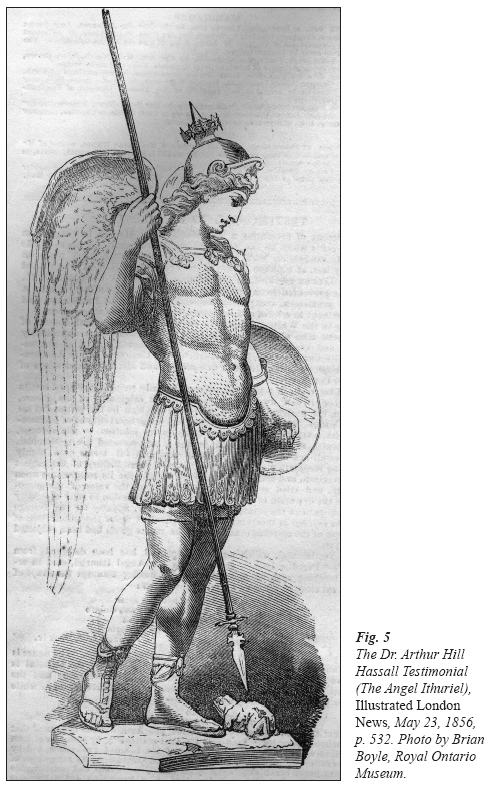

Fig. 5 The Dr. Arthur Hill Hassall Testimonial (The Angel Ithuriel), Illustrated London News, May 23, 1856, p. 532. Photo by Brian Boyle, Royal Ontario Museum.

Display large image of Figure 5

26 A daybook entry for May 23, 1856, reads: “A Statuette from a Design by Freret the subject from Milton’s Paradise Lost representing the Angel Ihurial [sic] discovering Satan in the form of a Toad. The Angel clad in armour . . . with a spear in his left hand touching the toad.”9 This exceptional piece is currently with Marks Antiques in London. Its overall height, including the pedestal, is almost 102 centimetres, while the statuette itself is just over 71 centimetres (Fig. 5). The inscription on the pedestal lends the additional information that the designer was the Reverend G. M. Braune and, more unusually, that it was “modelled by M. Frerèt [sic].” For all of its Christian allusions, the armour of the Angel Ithuriel is of an ancient Greek type, his stance is the contrapposto and, except for his wings, he is a Classical hero.

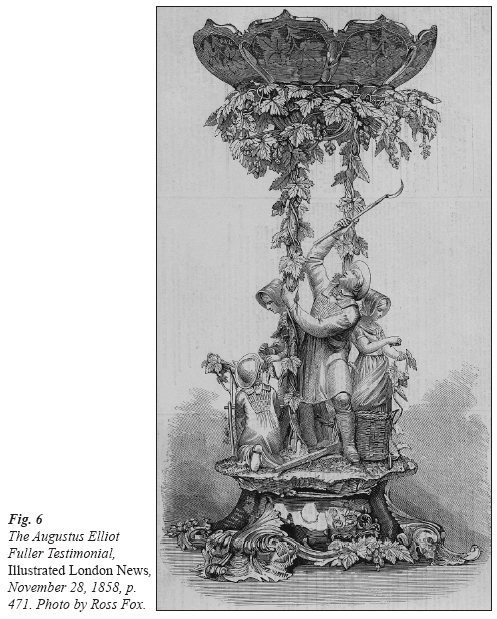

Fig. 6 The Augustus Elliot Fuller Testimonial, Illustrated London News, November 28, 1858, p. 471. Photo by Ross Fox.

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 7

27 A panel on the pedestal, with an image of a microscope and related apparatus, holds the key to the interpretation of the statuette. It is a metaphor for the scientific investigations of Dr. Arthur Hill Hassall, as explained in Illustrated London News (23 May 1856): “The Spirit of Good, as represented by the Angel, is employing Science, symbolized by the Spear, for the discovery of Truth, under the talismanic touch of which the fraud and falsehood of Adulteration, in the semblance of a Toad, spring to light.” Hassall was a physician and pioneer of applied microscopy in food adulteration, and an early spokesperson concerning its health risks. In recognition of his outstanding service as a food analyst, both Houses of Parliament and leaders in the medical and scientific fields awarded him with the Angel Ithuriel in 1856.10

28 Hop-picking was the subject of a sculptural group modelled by Fréret for a centrepiece of 1858 (Fig. 6)11 that was a testimonial for Augustus Elliot Fuller, MP for East Sussex, from the electors of that riding (ILN, 28 November 1858; Gentleman’s Magazine, 3 November 1857). East Sussex and the adjacent county of Kent were major hop-growing districts and Fuller, a large landowner and agriculturalist, was presumably a hop-grower himself. Hop-pickers were a popular subject of English genre painting throughout the late 19th century but were unusual as silver sculpture. However, vintage-type scenes—particularly with putti gathering grapes—were common in the decorative arts since the Renaissance, and particularly during the Rococo and Neoclassical periods, which is no doubt the source of inspiration.12 But the Barnard centrepiece exemplified naturalism as a Victorian style and the concept of Fréret’s figural group was based on drawings made from life by the landscape artist, Henry Gastineau. It was “genre” subject matter in the true sense, that is, a scene of ordinary people in everyday circumstances, for care was taken to depict clothing “and the different implements used by the labourers are exact models of the originals”(ILN, 28 November1858). Nevertheless, the artist sanitized harsh reality in a quasi-idyllic interpretation.

29 Another remarkable Barnard piece identified with Fréret is a ewer and stand set (Fig. 7) done in 1859 for the retail silversmith, West & Son of Dublin.13 It was a trophy for the Howth horse races, awarded by Archibald, 13th Earl of Eglinton, Lord Lieutenant (Viceroy) of Ireland. Reflecting its destination, the sides of the ewer had two reserve panels with horses in low relief, the lower handle terminal as a horse’s head, and statuettes of rearing horses on either long end of the stand. The Barnard records describe it as in the “Louis Quatorze” style followed by the parenthetical qualification “style irrégulier,” indicating the Rococo Revival. Generously embellished with C-scrolls and shell-work, it is the graceful fluidity of the highly plastic shape that speaks most strongly of the Rococo. It is almost proto-Art Nouveau in character.

30 An entry in the Barnard daybooks for December 16, 1859, indicates this ewer was reproduced together with another ewer of similar form where mythological scenes replaced the horses on the side panels, and the lower handle terminal was a dolphin’s head.14 Whether Fréret had a role in the second ewer is not known. Still another order by West & Son for a pair of ewers after the same designs—this time with stands—was recorded on June 6, 1860. On the stand of the mythological ewer, figures of tritons modelled by Fréret replaced the horses of the earlier ewer.15 Barnard repeated the design for the equine ewer as late as 1873, long after Fréret had left the firm.16

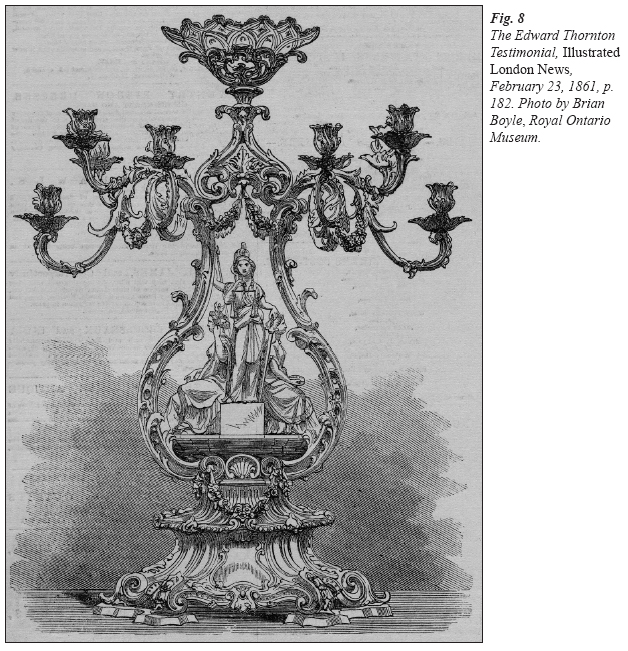

Fig. 8 The Edward Thornton Testimonial, Illustrated London News, February 23, 1861, p. 182. Photo by Brian Boyle, Royal Ontario Museum.

Display large image of Figure 8

31 Working with George Leighton, another Barnard modeller, Fréret modelled the figures on an especially elegant epergne-candelabrum by Barnard (Fig. 8). The piece was presented to Edward Thornton, British Minister Plenipotentiary to the Argentine Confederation (Argentina) in 1861 by the merchants and other British subjects in Montevideo, Uruguay.17 It was accompanied by four dessert stands, all in the Rococo Revival style. The epergne had four stems, two to each side, that were outwardly curved to resemble the profile of a lyre. Each pair of stems had five scrolled branches while framing a group of figures: Britannia, Justice standing with sword and scales, Prosperity seated with jewel casket and cornucopia, and Commerce seated with caduceus and rudder. They were an allegorical representation of the benefits of trade when “protected by British power” (ILN, 23 February 1861).

32 Only four references to Fréret are recorded in the Barnard daybooks from January 1861 until December 17, 1864, which is the last. He left the firm sometime after September 11, 1861, when Barnard filled an order for an epergne-candelabrum with group of “new” figures by Fréret.18 Because patterns could be reused—though initially made of wax, clay or wood, they were cast in white metal (a zinc alloy), lead, brass or other metals—a modeller’s name in a daybook entry does not necessarily mean the prototype was made at that time, but rather that a pattern after the modeller was used. The reuse of patterns is seen in a set of four figural salts, which were recorded for October 14, 1862, as from models by Fréret. Called High Life and Low Life, they represented two pairs of a young boy and girl, one well dressed, the other rustics, each holding a basket with a glass lining. A set of High Life with London hallmarks for 1865-66 is known. The patterns for Low Life still exist and saw revived usage by Barnard during the 1970s (Culme 1977: 68-69, 126-27).

Fréret in Canada: His Contribution to the Iconography of a New Nation

33 On March 5, 1863, Robert Hendery advertised in the Montreal newspaper, La Minerve, that he had newly employed Louis-Victor Fréret:Il saisit aussi cette occasion pour informer ceux qui patronisent son Etablissement qu’il s’est assuré les services d’un éminent artiste dessinateur français, MONS. FRERET, récemment arrivé de Londres, où il a été employé pendant plus de vingt ans dans l’Etablissement d’un des meilleurs Argentiers de cette grande ville.Considering the St. Lawrence River was icebound in winter, Fréret would have arrived in Canada no later than the previous autumn. Besides introducing Fréret, Hendery’s advertisement announced the commission of an epergne-candelabrum as a testimonial to the Honourable George-Etienne Cartier, which Fréret had designed as noted in the publication Les Beaux-Arts (1 June 1863).

34 Hendery was the largest silver manufacturer in what was then colonial British North America, supplying retail silversmiths from Canada West (Ontario) to Nova Scotia. A Scots immigrant, Hendery had apprenticed with Robert Gray & Son, the leading silver manufacturer in Glasgow. Completing his training at the end of 1837,19 he left for Canada the following year. English manufacturers were beginning to overtake Scotland’s declining silver trade, and likely accounts for Hendery’s decision to seek opportunities abroad. Ironically, English silver imports had an even larger place in Canada. Hendery started out in Montreal as a journeyman silversmith, eventually entering into partnership in 1851 with Peter Bohle as Bohle & Hendery. Within approximately six years, Hendery had begun his own operation. A determined entrepreneur, he adopted an aggressive business strategy to challenge the flood of silver imports. It proved to be relatively successful, as reflected in his firm’s rapid growth. Fundamental to this strategy was an expanded line of wares of more up-to-date design and varied decoration. During the 1830s and 1840s, the production of silver tableware in Canada was relatively low, consisting chiefly of flatware and small wares such as beakers, goblets, teapots and salvers, for example, with little or no decoration. To turn the situation around, Hendery engaged expert silver-workers from England; Louis (Lewis) Felix Paris (1812-1885), a specialist silver chaser from London was one such person working for Hendery by 1858. His greatest coup, however, was in attracting Louis-Victor Fréret (Fox 1985: 34-40).20

35 Clearly, Hendery wished to go beyond what had, until then, become the high end of his domestic output—tableware such as tea and coffee services, serving dishes, trays, bowls and presentation pieces such as ewers and vases—into the domain of grand display pieces in the English manner. Previously, all centrepieces and large honorific pieces were imported. Barnard was among the main suppliers, which partially explains why Hendery would have found it advantageous to enlist one of Barnard’s own designers and modellers. It was an ambitious venture by British standards for, with just six workers in 1863, Hendery’s operation was still small.21 The only Canadian silver manufacturer known to have made centrepieces prior to the 20th century, Hendery’s success was tied to a burgeoning population and a thriving colonial economy that was rapidly moving from craft production to industrialization—facilitated to a large degree by an influx of skilled workers from Britain and capital investment from Britain and the United States. Montreal was the hub of this industrialization (Lewis 2000: 3-40; Bumsted 1992: 297-302), a by-product of which was a heightened consumer appetite for luxury goods in silver.

36 The Cartier epergne-candelabrum is the earliest documented centrepiece by Hendery. A series of published announcements in Montreal newspapers from March through September 1863 attest to its intrinsic importance as a benchmark achievement in the history of Canadian silver-making, as well as to the prestige of the recipient as noted in the Les Beaux-Arts article (1 June 1863). The presenters were the constituents of the riding of Montreal East, which Cartier represented as Member of the Legislative Assembly of United Canada (today Quebec and Ontario). George-Etienne Cartier, one of the most influential Canadian politicians of his generation, was Premier of Canada East in the Cartier-Macdonald administration, from 1858 until 1862. As a nationalist he was in the vanguard of those who espoused federalist nationhood for the British-American colonies, which would become a reality in 1867. He also envisioned economic transformation, and was responsible for enacting government policies that fostered the development of a transportation, legal and financial infrastructure to support industrialization.22

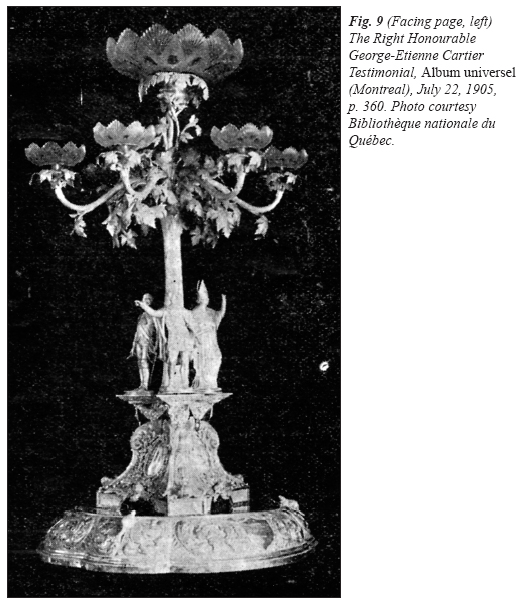

Fig. 9 (Facing page, left) The Right Honourable George-Etienne Cartier Testimonial, Album universel (Montreal), July 22, 1905, p. 360. Photo courtesy Bibliothèque nationale du Québec.

Display large image of Figure 9

Display large image of Figure 10

37 Appropriately, the Cartier epergne encapsulated an evolving Canadian nationalistic consciousness, both symbolically and pragmatically. By commissioning the epergne from a local silversmith, his supporters intended it to be a public gesture of encouragement to the development of home manufactures. This message was unequivocal: “C’est un devoir pour le public d’agir de même” (La Minerve, 5 March 1863). Fortunately, Fréret’s arrival enabled Hendery to accommodate these expectations.

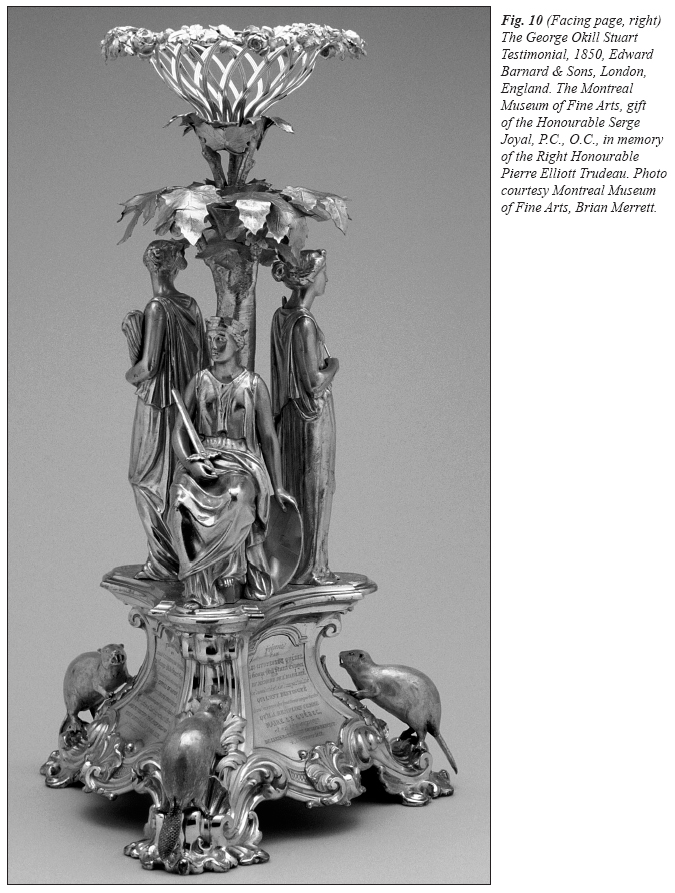

38 Today, the only known visual record of the Cartier epergne (Fig. 9) is an illustration that appeared in Album universel (22 July 1905). It adhered to a standard Victorian formula: a shaped tripartite base, tree-trunk-like stem and canopy of branches, surmounted by a glass bowl. Six branches each supported a small glass bowl or candle nozzle. The epergne sat on a highly decorated mirror plateau. In the fashion of the period, both the epergne and its plateau brimmed with symbolic motifs. The English character of the overall design was tempered by the generous distribution of maple foliage in an effort at “Canadianization.” Oak and palm trees occurred frequently enough in English centrepieces, but not the maple. The earliest instance of maple leaves decorating a centrepiece, known to the writer, dates from 1850 with Barnard (Fig. 10). But they were limited to a small cluster toward the top of a tree trunk, as opposed to a canopy. The Barnard centrepiece was also made specifically for the Canadian market: it was presented to George Okill Stuart on his retirement as mayor of Quebec City (Pepall 2006).

39 The origins of the maple leaf as an emblem are obscure. By the 1830s it was associated specifically with les Canadiens (French Canadians). Following the union of Lower and Upper Canada in the Province of United Canada in 1841, the maple leaf rapidly gained popular, but unofficial, acceptance as an emblem of the two Canadas. Evidence to this effect is seen in its proliferation in the decorations for the royal visit to Canada in 1860 of Albert Edward, Prince of Wales (Radforth 2004: 278-79, 286-87).23 But there was no unanimity as to its meaning, rather a lingering ambiguity that reflected French-English cultural divisions and conflicting views as to what constituted Canadian nationality.24

40 The beaver, another quasi-patriotic emblem, was also present in both the Stuart and Cartier centrepieces, in the form of three small castings. In the Stuart piece, they are attached to the base; in the Cartier piece, they were on the mirror plateau. The history of the beaver as an emblem of French Canada goes back to the 17th century. By the early 1840s it was often combined with the maple leaf, when both became identified with the French-Canadian patriotic organization, the Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste (Chouinard 1881: 12-15; Fraser 1998).25 These two emblems, as found on the otherwise English type of the Cartier epergne, evoke the spirit of a remark made by Cartier to Queen Victoria in 1858, that a Lower Canadian was an Englishman who spoke French.26 Unlike a great many of his French-Canadian compatriots, Cartier was an avowed monarchist and imperialist, a political stance that was reflected in two portrait medallions on the base of the epergne, one of Cartier himself, the other of Queen Victoria. The Montreal Gazette (18 September 1863) reported both medallions were wreathed with maple leaves.

41 A salient French-Canadian content was also present in the three statuettes on the base of the epergne. They represented a triad of historical notables of New France, in effect signifying those to whom George-Etienne Cartier was held to be the worthy successor. As described in the publication, L’Album universel (22 July 1905), there was Jacques Cartier, whose voyages of exploration formed the basis for France’s claim to Canada; François de Laval, the first Canadian bishop and Louis-Joseph, Marquis de Montcalm, who fell in battle while defending Quebec City against the British. Inclusion of Jacques Cartier bore an additional, highly personal meaning for George-Etienne Cartier. He and his family promoted the fiction that they were descendants of the explorer through his younger brother.

42 The appearance of emblems of a nationalistic character, as in the maple leaf and the beaver, belonged to a larger international phenomenon of emerging national consciousnesses that occurred during the 19th century, particularly in Europe and the Americas, and which was a factor in the revolutions of 1848. More specifically, they were symptomatic of a movement within the two dominant Euro-Canadian peoples to conceptualize a unique and symmetrical identity in the furtherance of nation building, while lacking the foundation of a long history and distinctive, shared culture. It amounted to image-making with emblems that had a potential to override ethnic, cultural, linguistic and religious differences and thereby convey a semblance of unity for the new nation-state. In 1862, Thomas d’Arcy McGee, one of the more articulate spokespersons of early Canadian nationalism, stated: A Canadian nationality—not French-Canadian, nor British-Canadian, nor Irish-Canadian: patriotism rejects the prefix—is, in my opinion, what we should look forward to, that is what we ought to labour for, that is what we ought to be prepared to defend to the death. (Burpee 1910: 79-83)There was a particular urgency to unify the British North American colonies owing to immediate and ominous threats from their large, bellicose neigh-bour in the United States, which was at civil war. Once Confederation was achieved, there followed an even greater push to articulate Canadian identity in symbolism, resulting in a surfeit of maple leaf and beaver emblems in the next several decades, when they truly became pan-Canadian motifs.

43 A comparable assimilation of quasi-nationalistic emblems occurred in the Australian colonies. From the late 1850s onwards, the kangaroo and emu became common motifs on honorific silver made either in or for Australia (Hawkins 1990: 1: 16, 106, 109; 2: passim). Overwhelmingly British and Irish, Australians were more homogenous as a people, and therefore spared the ethnic discord that existed in Canada. They were more secure in themselves and how they viewed one another. Extreme isolation, no doubt intensified by a lingering sense of ostracism emanating from their penal history, led to a heightened appreciation by Australians for the uniqueness of their environment. Original emblems of identity were ready-made in the local flora and fauna. This atmosphere was also more suited to the creation by local silversmiths of distinctly indigenous forms in honorific silver during the third quarter of the 19th century. The most celebrated are covered cups, caskets and inkstands consisting of silver mounted emu eggs and centrepieces/ epergnes/candelabra with figures of Aborigines and Australian landscape imagery, where the gum tree or tree fern often stands prominently (ibid. 1: passim; 2: passim). By comparison, a stricter reliance in Canadian honorific silver on essentially English designs during the same period is indicative of the endemic cultural and political insecurities of Canadians.27 The maple functions as little more than a substitute for the oak or palm tree, or grape vine of English epergnes. The dichotomy between Canadian and Australian silver centrepieces also rests to a certain extent with the silversmiths themselves and their training. A great deal of Australian presentation silver has a residual Germanic character in its general forms and fancifulness, in what is a distant indebtedness to 16th and early-17th century Mannerism. Many of the silversmiths were in fact immigrants from German lands, countries subject to German influence, or Scandinavia (James 2003: 134-35). In Canada, most of the highly skilled silversmiths engaged in the trade for honorific and table silver were immigrants from Great Britain.

Fig. 11 The Honourable Peter Mitchell Testimonial, Canadian Illustrated News (Montreal), September 19, 1874, p. 180. Photo by Brian Boyle, Royal Ontario Museum.

Display large image of Figure 11

Display large image of Figure 12

44 The Cartier epergne was the first of a series of four known examples produced by Hendery over a period of a decade or more.28 They are the only Canadian works that can be attributed to Fréret, though it is likely he did others. As in Britain, the contributions of individual silver workers usually were not publicized. Because Hendery’s epergnes share so many design elements, it can be surmised that Fréret must have had a hand in all of them, if for no other reasons than the limited size of Hendery’s operation, and the absence of anyone else known locally to have designed anything similar.

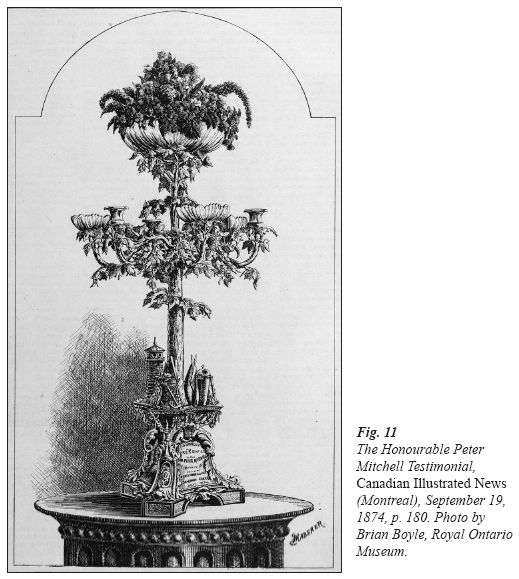

45 The quintessential distinguishing feature of all four epergnes is a canopy of maple foliage. Stylistically, they exemplify Victorian naturalism. The maple leaf was a frequent decorative motif on Hendery silver from about 1860; but it was, in particular, a theme of his centrepieces. These centrepieces are in two categories: the Cartier epergne-candelabrum and a close analogue, and two others that are a simpler variation on the first two. Instead of statuettes on the base, the Cartier analogue had castings of a lighthouse and various nautical apparatus and navigational instruments (Fig. 11). These referred to the Honourable Peter Mitchell as a shipbuilder, owner of the Mitchell Steamship Company and federal Minister of Marine and Fisheries. A native of Newcastle, New Brunswick, and Member of Parliament for the local riding of Northumberland County, the epergne was a tribute from his constituents in 1874. The decoration of the base was invested with additional allusions to Mitchell, too plentiful to enumerate. The cost of this epergne was reported to be “about $3,000” (Canadian Illustrated News, 19 September 1874). A journalist of the day further noted in that article: “It is too common a custom to order articles for presentation from England when their cost exceeds a couple of hundred dollars. Mr Hendery has shown that quite as good workmanship can be had in this country.” 29

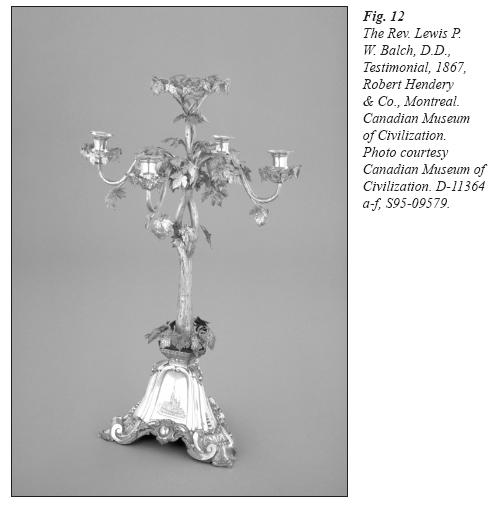

46 The other two epergnes are of simpler design, with a canopy of four branches fitted for candle nozzles and/or bowls, and a wreath of maple leaves replacing the cast elements at the top of the base. The Montreal Gazette (15 July 1867) identified one as an epergne-candelabrum presented in 1867 to the Rev. Lewis Balch, DD, Canon of Christ Church Cathedral, Montreal (Fig. 12). L’Opinion publique (27 June 1872) noted the other is an epergne presented in 1872 to Pierre-Joseph-Olivier Chauveau, Premier of the Province of Quebec.30 The stem of the Balch epergne differs from the others in that it splits half way up into two intertwining parts. A mirror plateau with cast maple leaf border accompanied the Chauveau epergne.

47 In these epergnes, Hendery demonstrated that he was capable of producing imposing articles of honorific silver, but only by enlisting the services of Louis-Victor Fréret—an accomplished designer and modeller from abroad. Yet, market conditions were not exactly favourable. As attested by the few epergnes discovered to date, consumer interest in this kind of work by Hendery was low, especially when compared to the production of Australian silversmiths. Canadians of wealth were certainly not lacking; moreover, newspapers of the time reveal a widespread usage of silver epergnes as testimonials in Canada. Nevertheless, for reasons over which he had no control, Hendery’s business potential was compromised by external competition.

48 In the Western world, the late 19th century was an era of burgeoning prosperity. The unprecedented scale of growth—fostered to a large degree by industrialization—engendered a veritable consumer revolution (Blaszczyk 2000: 3-4). Canada, like Australia, experienced a comparatively high level of per capita income.31 Both countries had their share of newly rich who flaunted their status through luxury consumption. Reflecting Canada’s British colonial legacy and attendant ethnic entrepreneurial imbalance, the majority of its parvenus were immigrants or the sons of immigrants from Britain, just as they were in Australia.32 Canadians, however, lived in a world of greater political uncertainty. As a new elite, they felt a strong compulsion to emulate the trappings of the upper class in the home country, in order to validate their claims to being loyal subjects of the world’s greatest empire. Certainly, a concomitant motivation was a desire for social recognition in Britain. So strong was the imperialist identification that many actually retired to Britain. This same outlook gave birth to the once much-used epithet, “Canada, Eldest Daughter of the Empire” (Lighthall 1889: xxi).

49 Preferring goods that carried the prestige of international production, Canada’s social elite looked to London and New York City for their luxury items. They preferred silver by Hunt & Roskell, Garrard, Hancock, Barnard, Tiffany, Gorham, for example, than domestically produced silver wares. As a result, a genuine trade in luxury goods did not establish itself in Canada. With the exception of furniture, even makers of moderately priced decorative arts were few in numbers. While some silverware was made locally, there was an almost total dependency on Britain—and to a lesser extent the United States and Europe—for fine ceramics and glass until the 1880s; even afterwards Canadian production was modest (Collard 1984: xvii-xix; Holmes 1974: 276). This situation was a lingering after-effect of earlier mercantilist policies, which restricted colonial manufactures. Consequently, consumer buying habits continued to be externally oriented.

50 Other local conditions handicapped Hendery’s ability to compete. Display pieces were typically large and required a great deal more metal than ordinary table silver. Silver was in short supply; little was mined in Canada before 1870. By contrast, silver was extracted in South Australia as early as 1841.33 Australia’s extreme geographic isolation also encouraged a local trade, just as it did in British India; it simply took too long to have an order filled in Britain. Canada’s adjacency to the United States and direct access to Britain, no doubt vitiated the development of a full-scale silver trade.

51 Within these constraints, Fréret achieved a modicum of success in Canada as a silver designer. His four epergnes are unparalleled in the history of Canadian silver. Moreover, the originality of their ornamentation, with their trenchant references to the new nation-state, contributed in a significant way to Canadian silver design. The political element within three of the four epergnes might explain their character as well as their relative rarity. Two were tributes to two Fathers of Confederation, the third to a Speaker of the Senate. Their destinations must certainly account for the abundance of maple leaves and other nationalistic imagery. Despite the fact that silver epergnes were otherwise imported, it can be conjectured that for these three pieces the presenters must have deemed it more prudent to turn to a home manufacturer.

52 These epergnes represent a special achievement for both Hendery and Fréret. In them Hendery surpassed the high-profile Glasgow firm of Robert Gray & Son where he had trained (McFarlan 1999: 220-21). No silver manufacturers in Glasgow produced honorific silver of this calibre during the 19th century. Instead, English manufacturing silversmiths supplied them as retailers. Glasgow silversmiths simply could not compete, although Glasgow itself was one of the great industrial cities of the Empire.

53 It is doubtful that Hendery employed Fréret regularly. By 1870, Fréret was engaged at the Canada Marble Works of Robert Forsyth in Montreal. Apparently, his Canadian phase was chiefly as a sculptor of statuary and ornamental stonework. Information on this activity is negligible; moreover, it is beyond the scope of this article. Fréret died in Montreal on January 11, 1879.

54 Louis-Victor Fréret epitomized the many multi-talented, but semi-anonymous artist-designers who were active in England during the early Victorian period—when the fine and decorative arts intersected and design was informed by fine art. France established the model for this kind of synthesis and, in fact, supplied England with many of its finest industrial designers. Most of these designers are little known today. Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse is one of the few exceptions to receive modern study (Hargrove 1976). Fortunately there are enough vestiges of Fréret’s career in documentary and early-published sources to enable an insightful glimpse of him as a designer and modeller. His legacy has a special resonance because he represents a rare case where the dissemination of design directly from the Great Britain to Canada, from London to Montreal, is identifiable in before-and-after works by an actual artist-designer.

References

Atterbury, Paul and Maureen Batkin. 1998. The Dictionary of Minton, rev. ed. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Antique Collectors’ Club.

Banister, Judith. 1980. Identity Parade: The Barnard Ledgers. The Society of Silver Collectors: The Proceedings 1974-1976 2 (Autumn): 165-68.

———. 1983. A Postscript to the Barnard Ledgers. The Silver Society: The Proceedings 1979-1981 3 (Spring): 38-39.

Bell, Quentin. 1963. The Schools of Design. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Blaszczyk, Regina Lee. 2000. Imagining Consumers: Design and Innovation from Wedgwood to Corning. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press.

Bouilhet, Henri. 1908-12. L’orfèvrerie française aux XVIIIe et XIXe siècles. 3 vols. Paris: H. Laurens.

Brett, Vanessa. 1986. The Sotheby’s Directory of Silver 1600-1940. London: Sotheby’s Publications.

Bridgeman, Harriet and Elizabeth Drury, eds. 1974. The Encyclopedia of Victoriana. New York: Macmillan.

Bumsted, John M. 1992. The Peoples of Canada: A Pre-Confederation History. Toronto: Oxford University Press.

Burpee, Lawrence J., ed. 1910. Canadian Eloquence. Toronto: Musson Books.

Bury, Shirley. 2000. The Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries. In The History of Silver, ed. Claude Blair, 157-95. London: Little, Brown and Company.

Cairnes, Clive Elmore. 1924. Coquihalla Area, British Columbia: Memoir 139. Ottawa: Geological Survey of Canada.

Chouinard, H.-J.-J.-B. 1881. Fête nationale des Canadiensfrançais célébrée à Québec en 1880. Quebec: A. Côté et Cie.

Collard, Elizabeth. 1984. Nineteenth-Century Pottery and Porcelain in Canada, 2nd ed. Kingston and Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Culme, John. 1977. Nineteenth-Century Silver. London: Country Life Books.

———. 1987. The Directory of Gold and Silversmiths, Jewellers and Allied Trades 1838-1914. 2 vols. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Antique Collectors’ Club.

Duro, Paul. 2005. Giving up on History? Challenges to the Hierarchy of the Genres in Early Nineteenth-Century France. Art History 28 (November): 689-711.

Dyce, William. 1840. Report Made to the Right Honorable C. Poulett Thomson, Member of Parliament, President of the Board of Trade, on Foreign Schools of Design for Manufacture. Parliamentary Papers.

Eatwell, Ann. 2006-2007. Saving the Barnard Archive for the Nation. Goldsmiths’ Review: 18-19.

———. 2007. Saving the Barnard Archives for the Nation. Silver Society of Canada Journal 10:26-31.

Ellis, Robert, ed. 1851. Official Descriptive and Illustrated Catalogue. Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, 1851. 3 vols. London: Spicer Brothers/W. Clowes and Sons.

Fogel, Robert William and Stanley L. Engerman. 1974. Time on the Cross: The Economics of American Negro Slavery. Boston: Little, Brown and Company.

Fox, Ross. 1985. Presentation Pieces and Trophies from the Henry Birks Collection of Canadian Silver. Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada.

Fraser, Alistair B. 1998. The Flags of Canada. Accessed 30 September 2007. http://fraser.cc/FlagsCan/.

Gunnis, Rupert. 1968. Dictionary of British Sculptors 1660-1851, rev. ed. London: The Abbey Library.

Hargrove, June Ellen. 1976. The Life and Work of Albert Ernest Carrier-Belleuse. PhD diss., New York University.

Hartop, Christopher. 2005. Royal Goldsmiths: The Art of Run-dell & Bridge 1793-1843. London: Koopman Rare Art.

Hawkins, John Bernard. 1990. 19th Century Australian Silver. 2 vols. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Antique Collectors’ Club.

Holmes, Janet. 1974. Glass and the Glass Industry. In The Book of Canadian Antiques, ed. Donald Blake Webster, 268-81. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company.

James, Jolyon Warwick. 2003. A European Heritage: Nineteenth-Century Silver in Australia. The Silver Society Journal 15:133-37.

Jones, Kenneth Crisp, ed. 1981. The Silversmiths of Birmingham and Their Marks 1750-1980. London: N.A.G. Press.

Knight, Stephen and Thomas Ohlgren, eds. 1997. Robin Hood and Other Outlaw Tales. Kalamazoo, MI: Medieval Institute Publications, Western Michigan University.

Lewis, Robert. 2000. Manufacturing Montreal: The Making of an Industrial Landscape, 1850 to 1930. Baltimore & London: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Lighthall, William Douw. 1889. Songs of the Great Dominion. London: Walter Scott.

McFarlan, Gordon. 1999. Robert Gray and Son, Goldsmiths of Glasgow. The Silver Society Journal 11:211-22.

Morris, Edward. 2005. French Art in Nineteenth-Century Britain. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Mouat, Jeremy. 2000. Metal Mining in Canada, 1840-195. Transformation Series 9. Ottawa: National Museum of Science and Technology.

Newman, Harold. 1987. An Illustrated Dictionary of Silver. London: Thames and Hudson.

Patterson, Angus. 2001. A National Art and a National Manufacture: Grand Presentation Silver of the Mid-Nineteenth Century. The Journal of the Decorative Arts Society 1850 to the Present 25:59-73.

Pepall, Rosalind. 2006. Silver Centrepiece. Ornamentvm 23 (Spring): 29.

Perkins, Roger. 1999. Military and Naval Silver: Treasures of the Mess and Wardrobe. Newton Abbot, Devon: privately published.

Plutarch. 1973. The Age of Alexander: Nine Greek Lives by Plutarch. Trans. Ian Scott-Kilvert. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin.

Pollen, John Hungerford. 1878. Ancient and Modern Gold and Silver Smiths’ Work in the South Kensington Museum. London: George E. Eyre and William Spottiswoode.

Radforth, Ian. 2004. Royal Spectacle: The 1860 Visit of the Prince of Wales to Canada and the United States. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Schiff, Gert. 1984. The Sculpture of the Style Troubadour. Arts Magazine 58 (June): 102-10.

Schroder, Timothy. 1988. The National Trust Book of English Domestic Silver 1500-1900. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Viking in association with the National Trust.

Simeone, William E. 1961. The Robin Hood of Ivanhoe. Journal of American Folklore 74 (July-September): 230-34.

Sparkes, John. 1884. Schools of Art: Their Origin, History, Work, and Influence. London: William Clowes and Sons.

Wainwright, Clive and Charlotte Gere. 2002. The Making of the South Kensington Museum I: The Government Schools of Design and the Founding Collection, 1837-51. Journal of the History of Collections 14 (May): 11-19.

Walford, Edward. 1878. Old and New London: A Narrative of its History, its People, and its Places. Vol. 6. London: Cassell & Company, Limited.

Wallis, George. 1863. Report on the Employment of Students of Schools of Art in the Production of Various Works of Ornamental Manufactures Exhibited by Producers and Manufacturers of the United Kingdom in the International Exhibition, 1862, in Tenth Report of the Science and Art Department of the Committee of Council on Education. In Parliamentary Papers.

———. 1871. The Art-Journal Catalogue of the International Exhibition. London.

Walton, Whitney. 1992. France at the Crystal Palace: Bourgeois Taste and Artisan Manufacture in the Nineteenth Century. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Ward-Jackson, Philip. 1985. A.-E. Carrier-Belleuse, J.-J. Feuchère and the Sutherlands. Burlington Magazine 127 (March): 146-51, 153.

Wardle, Patricia. 1963. Victorian Silver and Silver-Plate. London: Herbert Jenkins.

Warren, David B. et al. 1987. Marks of Achievement: Four Centuries of American Presentation Silver. Houston: The Museum of Fine Arts in association with Harry N. Abrams, Inc.

Watkin, Edward William. 1887. Canada and the States: Recollections, 1851-1886. London: Ward and Lock.

Werner, Alex. 1989. John Charles Lewis Sparkes 1833-1907. The Journal of the Decorative Arts Society 1850 to the Present 13:9-18.

Willms, Auguste. 1890. Industrial Art. Birmingham: Cornish Brothers.

Wright, Beth S. 1997. Painting and History During the French Restoration: Abandoned by the Past. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Young, Brian. 1981. George-Etienne Cartier: Montreal Bourgeois. Kingston and Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Notes