Dairy Pin-Up Girls:

Milkmaids and Dairyqueens

Meredith QuaileUniversity of Ottawa

Résumé

De pair avec la mécanisation de l’agriculture, à la fin du XIXe et au début du XXe siècle, les publicitaires ont développé des images stéréotypées du monde de l’agriculture afin de commercialiser les nouveaux outillages. L’image de la dairyqueen, laitière et pin-up, élaborait une notion fabriquée et romantique, à la fois de l’outil agricole et de la femme de la laiterie. Les publicitaires avaient saisi que, pendant que les femmes travaillaient à la laiterie, les hommes contrôlaient les finances et les achats dans les fermes familiales de l’Ontario. Pour cette raison, les publicités devaient être attractives pour les deux sexes. Cependant, les fermières de l’Ontario de la fin du XIXe et du début du XXe siècle persistaient à employer des outils dépassés et non mécanisés, malgré la possibilité de se procurer des appareils permettant d’alléger leur charge de travail, en augmentation constante dans les laiteries. Cet article discute de la juxtaposition de l’image idéalisée de la dairyqueen et de la vie quotidienne des fermières de l’Ontario, tout en signalant la dévaluation idéologique sous-jacente du travail des laitières au cours de cette période.Abstract

With the rise of agricultural mechanization, during the late-19th and early-20th centuries, advertisers developed stereotyped agricultural images to market newly-developed technologies. The “dairyqueen” pin-up image projected romanticized and constructed notions of both the tool and the milkmaid. Advertisers understood that while women worked in dairying, men controlled finances and purchasing on the Ontario family farm. For this reason, advertisements needed to appeal to both genders. Meanwhile, Ontario’s 19th- and early-20th-century farmwomen persisted with out-moded and unmechanized tools, despite the availability of labour-saving devices and the ever-increasing dairy workload. This article discusses the juxtaposition between the idealized dairyqueen image and the Ontario farmwoman’s daily life, while also indicating an underlying ideological devaluation of dairywomen’s work during this period.1 “Women’s work” on the 19th- and early-20th-century Ontario farm meant not only milking cows, but all activities related to that task. Ironically, late 19th-century manufacturers of dairy equipment advertised their newly-developed machinery using pin-up-type images, here called dairyqueens.1 This term implies that the characteristics of these images—which portrayed dairywomen as apron-and bonnet-clad, wearing their Sunday best while happily smiling from either the side of a cow or from behind a cream separator—were overwhelmingly idealized. Ironic, since these stereotypical, centerfold-type images and dairy pin-up girls were diametrically opposed with the drudgery of farm work, considering that the barn—where the majority of work took place—was dark and malodorous, and the toils of the dairy process were onerous.

2 Undoubtedly, there is challenging physical labour involved in dairying. There are monotonous and repetitive chores: the moving and cooling of milk, along with the cleaning of dairy equipment and the tending and care of animals. A turn-of-the-20th-century dairy farmer’s wife had a continuously arduous job. While contemporary agricultural journals sought to spread useful information to homes and farmer’s wives, while also displaying advertising images of idealized dairyqueen pin-ups, it is clear from published articles that dairywomen were encouraged not only to do their tasks well, but to look good doing it. This was a job in itself, to maintain femininity, sexuality and attractiveness when working daily with sour milk in a manure-filled barn or smoky kitchen. The message in these advertisements, nevertheless, was relayed that women should work as hard as men, with less leisure, and still keep their aprons clean, their hair tidy and a smile on their faces. Essentially, the dairyqueen ideal indicated farmwomen should happily, prettily and efficiently go about their daily routine even without mechanization—or so suggest images in dairy advertisements.

3 This article emphasizes, first, the drudgery of the milkmaid’s work contrasted against the stereotypes and iconography of the dairyqueen pin-up. Second, three areas of historical scholarship, including women’s history, material culture and advertising theory, which inform this study, are presented. Necessarily addressed is the challenge facing the application of separate spheres ideology to contemporary rural women’s history research. In terms of sources, material culture objects and the icons portrayed on their surfaces are discussed as alternate avenues of analysis for this study. Additionally, the photographic work of Reuben Sallows is considered, as he often photographed the dairyqueen ideal. Finally, socially-constructed style standards, in terms of aesthetics and fashion, contrasted against the common workload for the Ontario dairywoman, indicates the increasingly broad division between dairy process and dairy advertisement during this period. This division between milkmaid and dairyqueen highlights the undercurrent of devaluation surrounding dairywomen’s work with the advent of mechanized dairy tools and their advertisement.

4 Historiographically, three linked areas of research frame this study of dairywomen’s work and the dairyqueen ideal. The first is the ever-present discussion surrounding the challenge facing those researching women’s history. The second is the use of physical objects—material culture, primary sources—used to typify the difficulty and stereotyping of dairywomen’s work. The third and predominant discussion in this paper is based on Jackson Lears’s scholarship regarding advertising theory in 19th-century agricultural advertisements and its analysis. Lears’s work was essential for this paper because most other historians of technology focus on men and the types of farm equipment they most often used (Blandford 1976, Barlow 2003, Benoit et al. 2003). Studies dealing with domestic technology and housework rarely touch on advertisers or advertisements.2 Accounts of milkmaids’ daily work juxtaposed against the ideal images of the dairyqueen comprise the crux of this paper.

5 Carolyn Sachs terms the dairywoman “the invisible farmer” (Cowan 1983: 88). Commonly, women were not included in historical, written and primary sources and consequently remain excluded from certain methods of research. Scholarship surrounding rural women’s history, with the application of material culture and especially technology, guides this study. When linked with other primary sources, analysis of advertisements and photographs of Ontario dairywomen indicate the types of work dairywomen did, as well as the stereotypes, ideals and potential drudgery ascribed to both the milkmaid and the dairyqueen. Joan Jensen (1988) notes:…rural women remain an elusive majority. Omitted from most agricultural histories because they were not the owners of American farmland, slighted in labor histories because their work was different from that of males, and neglected by histories of women that concentrate on the urban middle and working classes, rural women are barely visible …. (813)Although dairywomen left few written records, there is evidence of their daily lives through material culture, such as their dairy tools and, particularly for this study, contemporary photographs and advertisements.

6 This discussion, due to its links with work and gender, relies on research pertaining to the object-based, material culture study of domestic technologies. Hand-powered tools composed the everyday objects familiar to the milkmaid.3 The way these tools were advertised and used clearly contributes to an analysis of women’s work, especially with regard to the overarching stereotypes of the dairyqueen, contrasted against the methods and types of cyclical work associated with the Ontario milkmaid.

7 Jackson Lears’s discussion on North American advertising themes and trends informs the analysis of the images discussed here. Lears’s approach to advertising theory reveals that for 19th-century North American advertisers, dominant thematic trends emerged. His analysis demonstrates how agricultural advertisers portrayed dairywomen in 19th-century Ontario as dairyqueens: idealized and constructed images of what a farmer’s wife looked like and what she could achieve, as opposed to toiling and exhausted milkmaids. Not projected by accident or dictated by aesthetics alone, the dairyqueen ideal existed as a consistent theme in all agricultural advertising, shaped by dominant contemporary trends in advertising, primarily through the concept of nostalgia. These themes became prevalent in agricultural advertisements, specifically: nostalgia and rural abundance, the icon of the female linked with images of pastoralism and maternalism. In order to offset massive upheaval, due to the rapid pace of agricultural change during this period, advertisers attempted to “create memory” or fantasy. Essentially, images and icons in advertising created a backwards glance at a romanticized version of agriculture as associated with comfort, home, prosperity and contentment. According to Lears, advertisers developed images to create a seeming link with a conceptualized, and idealized, past using icons both exotic and agrarian (1994: 4). These idealized rural themes appear clearly in advertisements for dairy technology, through the dairyqueen iconography, stereotype and ideal, from the late 19th and early 20th century.

8 The concept of rural abundance—an ideal of either home or mother—projected an image of comfort and plenty, but implicitly objectified women in dairy advertisements. In his introduction, Jackson Lears states: “…advertisers’ efforts to associate silverware with status or cars with sex were a … well-organized example of a widespread cultural practice” (1994: 5). The nostalgic pastoral, or motherly connection is described by Lears as: “Longings for links with an actual or imagined past, or for communal connections in the present” (1994: 5). Advertising images implied that there existed a time when farming was simpler and wives unworn from the dregs of farm work, drawing on the contemporary advertising themes of nostalgia and placing them in a marketing context, using sexualized dairyqueens to convey the idea and ideal.

9 Overarching advertising trends and themes, as described by Lears, are portrayed within dairyqueen marketing images in mainly three ways: attractiveness, profitability and hygiene. Fashion, style, beauty, cleanliness and overall surroundings are themes broadcast explicitly yet subtly in dairy advertisements. The main emphasis and consequential focus of advertising images, however, was on portraying these dominant themes through female physical beauty. Numerous agricultural machinery companies continually promulgated the “dairyqueen” aesthetics of beauty in advertisements from the 1860s to the end of the Second World War. The object is not to argue that Ontario milkmaids were attempting to dress or look like dairyqueens but, as the advertisements were pervasive and effective, the beauty ideals and “look” of dairyqueens almost certainly had an impact on dairywomen. It is difficult to state in a preliminary study exactly what this impact was, but it is clear that the projected ideal did not match the reality. The lack of access to modern dairy technology clearly devalued and left unacknowledged the actual labour of the milkmaid. Although we understand from Lears that trends in advertising suggested women “look” a certain way for physicality and attractiveness, the daily toil involved in 19th-century dairying was not conducive to rosy cheeks, clean skirt hems, arranged hair or scrubbed hands—especially not with increased milk production and heavier workloads for Ontario milkmaids. The dairyqueen image seemed almost blissfully ignorant to actual milkmaid’s work, while the Ontario milkmaid was as ignorant to the benefits of the dairyqueen’s mechanized advantages.

10 Over the past thirty years social historians, especially those focusing on rural women’s history, asserted that alterations in gendered-work definitions and the introduction of technology have been identified as possible causes for the removal of Ontario farmwomen from the dairy process. Attempting to understand how technological change affected gendered work roles, historians frequently frame their work with the concept of separate spheres—or the gendered division of labour—and its definitions of work. Separate spheres as an analytical tool, however, has come to be considered outdated within historical scholarship. Yet methodological trends cannot discount how dominant and prevalent separate spheres ideology was in organizing agrarian work during the 19th and early 20th century.

11 During this period in Ontario history, the family production unit clearly divided their labour along gender lines. Certain types of work such as butter-making or plowing required specific skill sets and tools. The application of a separate spheres ideology to this study, frames the understanding of work, under which Ontario dairywomen of this period laboured. This ideology has largely guided rural women’s social history scholarship. In more recent work, however, as with all trends, this concept of a gendered-division in Ontario agricultural labour has been essentially dismissed, due in part to an increased acknowledgement and emphasis on the mutuality of work within kinship ties on the family farm (Osterud 1991). Separate spheres ideology is not, however, merely a construction of contemporary scholars. This notion of divided work roles was dominant in rural Ontario society. While both women and men undoubtedly helped one another during harvest time, with exceptionally difficult tasks, dairywomen’s own words and writings—as well as the continual existence of their dairy-specific tools—indicates a perpetual divide within the family farm work day.

12 Dairywomen themselves described a “sphere” or “circle” within which they laboured. One dairy-woman wrote:It is such a narrow circle in which to revolve…. But to think, how my time and limited strength is largely employed in these commonplace duties, my leisure needed for proper rest.… (Her Circle, 1880, quoted in Juster (1996: 281)The title of the publication from which the above quote is taken confirms that sense of working within a circle, primarily because of gender. The woman’s words reveal her work as repetitive, perfunctory and physically exhausting.

13 Work roles were defined not by gender alone, but by both the space and the tools associated with them. Divisions of work, by the space where the labour was performed, extended this ideological, sexual division and sensibly, chores connected with certain areas of the farm fell under either “women’s” or “men’s” work.4 The obvious spatial and architectural construction of Ontario farms—with separate dwellings for animals and humans—immediately dictated the division of domestic and farm work. Only with the re-categorization of milking as a male chore toward the end of the 19th century, were women’s roles diminished in one aspect of Ontario dairying. The fact historians marked this shift also reveals the continually gendered nature of Ontario farm work. That historians perceived a transitional switch in dairying, from female to male labour, indicates the strength of separate sphere ideology as a template for analysis, as well as a societal norm, in 19th- and 20th-century Ontario.5

14 Milkmaids and their work lie in stark contrast to the pictured idealized dairyqueen here presented. Historians of agriculture and rural women’s history concur that dairywomen increasingly became overburdened with daily chores and worn down by the never ending-routine of hard work. In discussing her theory concerning the supposed decline of Ontario milkmaids due to economic change, Marjorie Griffin Cohen comments on the arduous, multiple tasks of dairywomen:But aside from the distastefulness of dairying, even only one or two cows were a heavy workload for farm women, both because of the back-breaking conditions under which the labour was performed and because of the multiplicity of additional tasks which were the total responsibility of farm women. (1988: 99)As Cohen indicates, there existed two main problems facing Ontario dairywomen: an overwhelming amount of work and a lack of adequate tools. There was not only milking to do but also all the associated chores, as well as a myriad of other daily, seasonal and necessary work. Historians explain the type and amount of work dairywomen completed as gender and technology related. Chores related to the house and not to the barn, even when completed outside of the house itself, such as gardening, laundry, or dairying, were linked with women’s traditionally gendered work roles.

15 Daniel Cohen (1982) notes that domestic, household and dairy technologies were meant to lessen the work load for women, but in cases where the tool was well made, these objects made women more efficient and thus capable of taking on more duties. While most often Ontario farmwomen did not gain access to mechanized tools, their fathers, brothers and husbands invested widely in harvest machinery and improved outbuildings. Technology, therefore, did not free up women’s time for leisure. Instead, more ineffective and continually expensive technologies were produced to ease women’s ever-increasing work burden, which thereby perpetuated the treadmill-like work of milkmaids. Apart from whether dairywomen unduly toiled due to rigid gendered-work roles or due to a lack of access to technology, it is clear the dairyqueen image in advertising did not convey the reality of a dairy-woman’s day; nor did the image reflect the amount of work and the labourious nature of the tasks that comprised a dairywoman’s day. This purposeful representation of the dairyqueen as an ornament, rather than as a productive unit, demonstrated an ignorance and denigration of dairywomen’s toil and devalued farmwomen’s work in the process.

16 The introduction of technology onto the 19th-century Ontario dairy farm brought with it an advertised idealization, of women and milking, inconsistent and non-reflective of dairywomen’s daily work. Due to the dichotomies between the milkmaid and the dairyqueen, accounts of actual Ontario dairywomen are here contrasted against the perfected facade and image of the dairyqueen projection. A never-ending cycle of daily, weekly, monthly, seasonal and yearly chores made for a treadmill-like effect in farmwomen’s lives. Working an average of more than eleven physically and mentally exhausting hours per day, descriptions of farmwomen’s work point out the blatant contrasts between real milkmaids and the perceived ideal (Kline 1997). Milkmaids could not maintain, or even attain, the dairyqueen ideal when a dairywoman’s space and tools were habitually described as McNerney (1991) notes:[The kitchen] accommodated not only cookery (and smoke) but the 24-hour-a-day existence, along with paraphernalia for sewing, spinning, weaving, churning, making jams, jellies, preserves, pickles, baskets, candles, ad infinitum. (6)Monda Halpern (2001) points to the overwhelming work dairywomen faced. In her monograph she writes:Most of the farm wife’s time was consumed by arduous household demands. These included domestic, productive, and reproductive work, and the care not only of husbands and children, but of infirm relations and farmhands. (27)6Reinforcing the notion of the overworked farmwife, in 1868, The Farmer’s Advocate included this article from one of their most popular female columnists: Next to being a minister’s wife, I should dread being the wife of a farmer. Raising children and chickens, ad infinitum, making butter, cheese, bread; and the omnipresent pie, cutting, making and mending the clothes for a whole household, and not to speak of doing their washing and ironing; taking care of the pigs and the vegetable garden; making winter-apple sauce by the barrel, and picking myriads of cucumbers; drying fruits and herbs; putting all the twins through the measles, whooping cough, mumps, scarlet fever, and chicken pox; After the supper is finished comes the dish-washing, and milking, and the thought for to-morrow’s breakfast; perhaps all night she sleeps, and rises again to pursue the same un-relieved treadmill, wearing round the next day. (Fern 1868: 19)This description of a farmwoman’s daily workload, written by a very successful dairywoman, does not match the dairy advertisement iconography of beauty, profit and hygiene. Daily, Ontario farm-women greeted the new day with woe, confronted by a lack of access to dairy tools, little aid from their farmer husbands and seemingly unending toil.

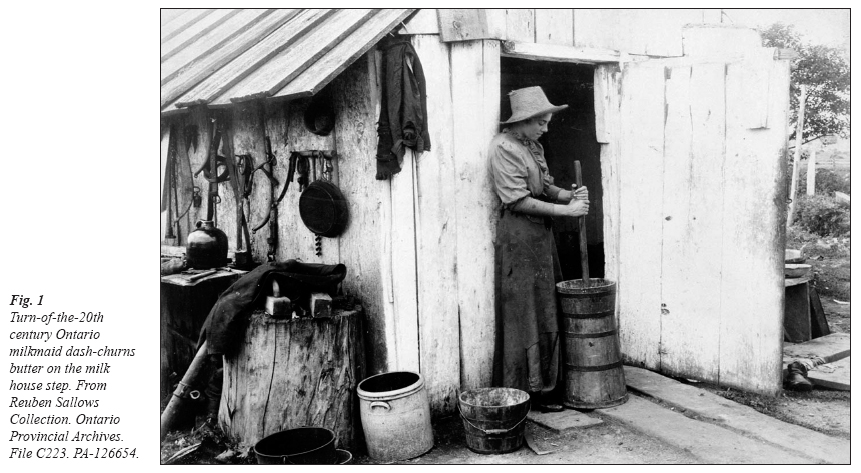

Fig. 1 Turn-of-the-20th century Ontario milkmaid dash-churns butter on the milk house step. From Reuben Sallows Collection. Ontario Provincial Archives. File C223. PA-126654.

Display large image of Figure 1

17 In a rare photo of a milkmaid at work (Fig. 1) the lack of technological or mechanized improvements is obvious. We can see the everyday objects of 19th-century Ontario farm life scattered around the milkmaid, among them the hand tools for making butter: a wooden milk pail, one-pound butter press and mold, butter crock and butter bowl. She likely removed her tattered shawl or dress jacket that hangs to the left, to complete her long and difficult churning chore. Explicitly, we see a young woman with her sleeves rolled up working at a crude dasher churn. The stains on her dress sleeve and her torn skirt present an image of work attire that is both practical and well-worn. This young milkmaid’s hair was completely covered, not with a bonnet but with an economical and practical straw hat. In all likelihood, the churning was but one of her numerous daily tasks. This milkmaid worked not so smilingly in less-than-ideal circumstances, in the doorway of her rough, yet whitewashed milkhouse, which loosely housed her dairy tools upon uneven boards.

18 Ontario milkmaids had to deal with more than never-ending cycles of work. Typically, men controlled farm finances and made decisions about purchasing new technologies for the farm. Advertisers understood this and dairyqueen sexuality was consequently aimed directly toward men. Dairyqueens were models for beauty, health, hygiene and productivity, all stereotypically desirable traits for a farmwife and the dairy industry. Farmwomen, or milkmaids, were exposed to agricultural magazines and advertisements and placed pressure on their husbands to purchase labour-saving devices with attractive ads. Farmers’ common indifference to their wives working needs was often relayed through letters and comments submitted by dairywomen to Ontario agricultural journals such as The Farmer’s Advocate. In 1897, A Friend to Farmer’s Wives wrote:…but housekeeping on the farm means so much more heavy work than in the city. I do not mean to complain of our dear husbands, but I will say that when they are well fed and kindly cared for they are very apt to become indifferent and heedless, neither thinking nor caring how hard the family has to work under many difficulties. I think the trouble is the farmer’s brains are so absorbed with fine horses, fine barns, thoroughbred cattle, and every convenience on the farm to make work easy that he quite forgets how his family is struggling to make his home comfortable and attractive … a farmer’s wife has so much to try her nerves. Farmers should appreciate everything their wives do, not look on them as if they were a machine or a football; they are human beings, and want to be treated as such. (282)Within this passage, an Ontario farmwomen requested some modicum of respect and relief in terms of her work. The author emphasized how farmers strove to improve their agricultural sphere, yet how farmwomen were neglected in terms of acknowledgement or investment, despite their physical and economic contributions to their farms. Social norms ascribed to gender and technology, and linked with financial control on the farm, perpetuated the wretched state of Ontario dairywomen. Commonly, especially beginning in the 1880s when agricultural advertisements appeared in earnest, disgruntled farmwives voiced their disappointment and sometimes outrage at being the last consideration on the family farm.While the various operations of the farm are being carried on by the help of valuable labor-saving machinery, are not far too many farmers a little negligent in regard to the conveniences provided for performing the never-ending work of the kitchen and dairy-room? (Juster 1996: 149)Marjorie Griffin Cohen’s socio-economic study on women’s work in Ontario indicates this lack of investment in dairywomen’s sphere was customary. Farmers exerted economic control over their wives, linked with gendered work on the Ontario family farm and principled by the predominant contemporary and historical notion of separate spheres ideology. Cohen (1988) writes:Dairy equipment tended to be primitive and improvements in technology were slow to be used widely on farms. Generally this was not because dairy women were skeptical about using them, but because they had little control over capital expenditures on farms. (99)From the perspective of male economic or purse-string control, the dairy pin-up girl construction, or dairyqueen, was indeed an attractive marketing tool. Not only did the dairyqween ideal appeal to the sexual sensibilities of men, but she also evoked nostalgia through maternalism, and depicted money-saving and earning potential if the applicable product was purchased: in all, an enticing package. More importantly, the dairyqueen ideal encouraged dairywomen with the promise of improved working conditions, hygiene standards and profitability, thereby suggesting the farm wife “nag” her husband for the advertised technology. With profitability, hygiene, an improved product, perhaps less nagging from the wife and the beauty of a dairyqueen image in the barn to tempt him, what farmer would say no to purchasing a cream separator or improved butter churn?

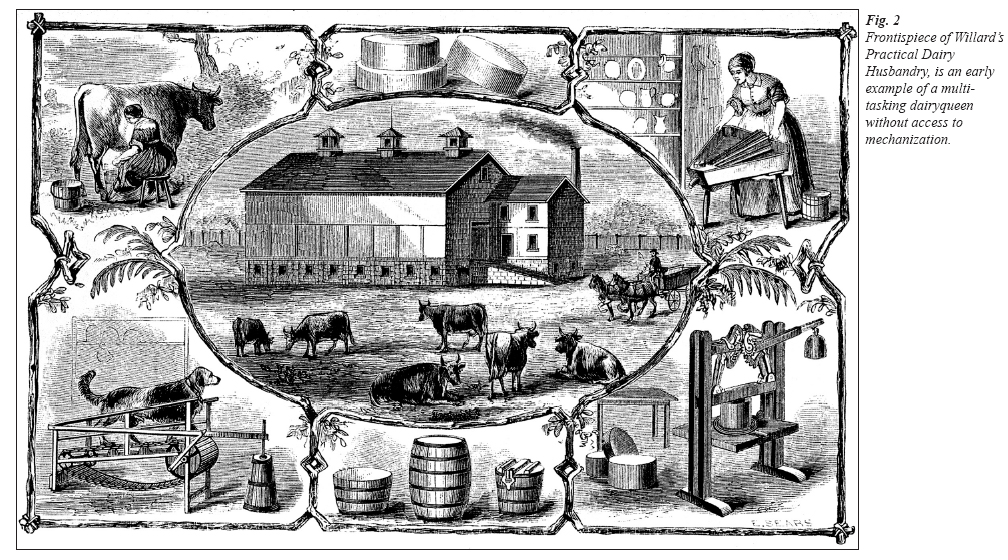

Fig. 2 Frontispiece of Willard’s Practical Dairy Husbandry, is an early example of a multi-tasking dairyqueen without access to mechanization.

Display large image of Figure 2

19 By 1877, when A. Willard’s book (Fig. 2) was published, development in dairy technologies had been under way for at least a decade and agricultural technology companies had begun using the dairyqueen image to sell products and tools. Although Willard’s book was written by a man, for a male farmer audience, the dairy labourers depicted are female. This dairyqueen image is divided into different sections of butter and cheese production that illustrates a woman milking, a dog churning butter with a treadmill attachment, a woman working butter in her kitchen and a cheese press in use. Together the images convey the primary unmechanized, butter-related chores of: milking, churning, working, washing, salting and the pressing or shaping of butter. The central image of the plate shows a prosperous and well-established farm with contented shorthorn dairy cows in the yard, and the gentleman farmer driving his carriage. The engraving illustrates the dairyqueen employing an unmechanized, and likely unruly, butter-worker table to ease her chores. All the same, the woman’s dress and apron, along with her tied-back hair, all appear neat and tidy. The images combine to infer that the information included in the book’s text will lead to prosperity and comfort for any farmer and his hard-working dairyqueen.

20 Dairy pin-up-girl images in advertising appealed differently to farmers and their wives once the prospect of new technologies emerged in the province. While 20th-century advertisers aim their media at garage mechanics, who turn over their calendar each month to reveal another beautiful and scantily-clad girl, 19th-century farmers posted parallel forms of pin-up-type advertisements in their working and living spaces. Not surprisingly, the concept of marketing to men, who usually purchased technologies, through the lure of beautiful women, is as old as advertising itself. During the broad period studied for this paper—between 1865 and 1914—agricultural technology companies sent out calendars, advertisements, pamphlets and handbooks, as well as small and useful household necessities, such as match holders, tea trays, pin books, thermometers and boot cleaners, that displayed the image of a dairy pin-up girl. The images presented in this essay range from approximately 1877 to 1907, a forty-year span during which the marketing of dairy tools exploded. The dairyqueen image remains ideal and idealized: beautiful, young, efficient and happy in her work.

21 Farmers and their wives placed, and used, advertising objects in their homes, milkhouses and barns. Consequently, they surrounded themselves not only with marketing testimonials but also with concepts inconsistent with the reality of living and working on a dairy farm. Advertisers constructed an ideal image of women in dairying to sell machinery. That image, while it appealed to mainly male buyers, also attracted female interest. Dairywomen, who did most of the labour, craved new technologies to relieve their drudgery, and measured themselves against an unattainable standard.

22 Gustav De Laval was a dairy technology company owner who, in 1878, perfected his invention and received a patent for his centrifugal cream separator.7 An onslaught of similar-type separators, based on the same principles, deluged the machinery market. He distributed promotional items, such as tea trays (Fig. 3), to customers who purchased their separators or other equipment. Used for tea service or simple meals, this type of functional object could also be displayed in the farmhouse. The image on the practical tray portrays a rich example of the dairyqueen stereotype, is beautifully drawn and illustrates the comforts available to those who employed De Laval’s superior technologies. The lovely dairyqueen pictured on this object wears a beautiful, shape-revealing and sumptuous-looking red dress, covered with a white bib-apron.8 Her stereotypically small waist, creamy skin and hair neatly arranged on the top of her head, illustrate ideals of beauty and health for the period. This dairyqueen works in a comfortable and hygienic atmosphere, most likely in her kitchen or an adjacent summer-kitchen. The scene around her is of abundance; there are numerous large cans of milk waiting to be separated, her little boy—impeccably dressed—carries a small pail of skim milk from the separator to expectant calves just beyond the door. In the detailed background, notice a rustic farm at the time of afternoon milking, a tidy barnyard, and the dairyqueen’s husband returning from the barn with pails of milk to be separated by his conscientious wife. Profit, hygiene, kinship ties, comfort and beauty are all artfully extolled and thereby advertised in this pleasant and idyllic scene.

Fig. 3 A turn-of-the-century De Laval advertising object from Henry Stahl private collection. The “dairyqueen’s husband” referred to is just visible at the extreme right, just above centre. Image courtesy De Laval Inc. Canada.

Display large image of Figure 3

23 The dairy pin-up appeared not only on promotional objects but in print advertisements in widely distributed agricultural journals and papers. As well, historian Lynn Campbell’s paper outlining the life and work of Ontario commercial and artistic photographer, Reuben Sallows, indicates how his work illustrated rural life in Ontario, especially between 1876 and the First World War.9 Sallows was a professional photographer who shot both staged and unstaged rural scenes selling his photos to dairy technology companies, such as De Laval. Often captured by Sallows, dairyqueen beauty standards of the day are visible in his advertisement and stock photos. Most often, the women were posed with neatly arranged hair in an up-do in their most pleasant attire, usually covered by a pristine, white bib-apron. Dairyqueens were unfailingly young, beautiful, smiling and depicted as completing their chore with little effort, thanks to their labour-saving tools. To convey the impression of hygiene in the dairying process the dairyqueen’s clothes—often of white or light-coloured cloth—the machinery and surroundings were pictured as dirt- and germ-free, which is the best environment for producing superior milk, cream and butter. Notably, the background for the dairyqueen was always picturesque. Rarely working in the standard barn, stable or milkhouse, dairyqueens posed in comfortable homes—a pasture, an orchard or in some such bucolic location.

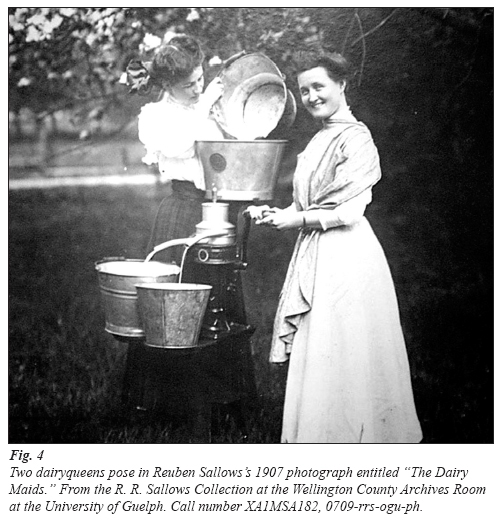

24 One excellent example of Sallow’s out-of-place dairyqueens wearing un-farm-like attire, features two dairyqueens situated against the backdrop of a springtime orchard in bloom (Fig. 4). Both of them operate the separator; one pours milk into the top while the other smiles at the camera and simulates turning the crank mechanism. Both dairyqueens are inappropriately dressed for dairy chores. The girl on the left wears a ruffled, white blouse and tartan skirt, while the girl on the right wears a white, high-collared dress with a stylish paisley shawl. Such apparel is too fine to be worn to the orchard or barn for work. It is unlikely milkmaids ever emerged from the milking parlour so unscathed. Neither dairyqueen seems tired or strained from her work, despite the amount of milk and cream this large separator could process. The weight of the filled milk pails and the continuous and steady cranking action required for proper skimming would certainly have fatigued any milkmaid. Yet, the dairyqueen facing the camera is the picture of composure—smiling and lovely.

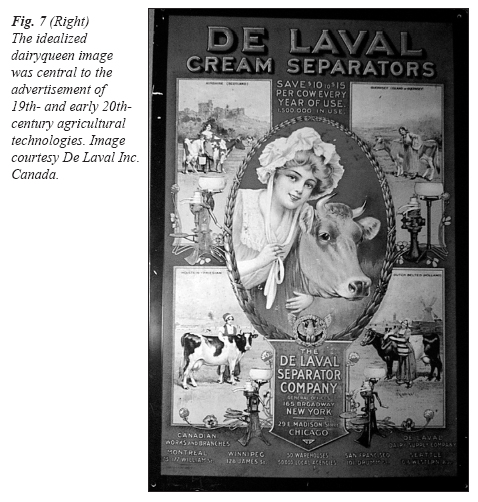

Fig. 4 Two dairyqueens pose in Reuben Sallows’s 1907 photograph entitled “The Dairy Maids.” From the R. R. Sallows Collection at the Wellington County Archives Room at the University of Guelph. Call number XA1MSA182, 0709-rrs-ogu-ph.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 5

25 In an analysis of the same Reuben Sallows image, Campbell warns of the photographer’s propensity for shooting “pretty pictures” or staged images of rural Ontario life.Two pretty girls are portrayed operating a cream separator in an orchard. To Sallows’ audience of the day, the incongruities in this scene would have been obvious. Cream separating was not a task to be performed … outdoors, if for no other reason that a cream separator would not work unless secured to a flat surface. To the modern viewer, inconsistencies are not nearly so apparent and therefore there is a danger that images such as these will be accepted as historical fact. (1988: 9)Indeed, this danger would be great if other sources did not exist to counter the dominance of dairyqueen pin-up images. In her footnotes, Campbell states that despite challenges with such contrived sources, “the backgrounds, clothing, and other incidentals” within Sallows’s work “are of great help,” in reconstructing Ontario’s past. For the purposes of this study, the incongruities themselves reveal much. Campbell remarks on the photographer’s capability of casting the developing province in a positive light:In the photographs of rural Ontario it is almost always spring or summer and sunny. As a whole, they give a very appealing view of rural Ontario, far removed from the despair and poverty of … the reality of life in rural Ontario. (1988:10)For commercial purposes Sallows often photographed for the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture and Food as well as for agricultural journals and machinery companies. He therefore hoped to portray the province’s rurality in a positive light by capturing it in its best seasons.

26 Utilizing alternate primary source material, a glimpse can be viewed of the bleak “reality” Campbell mentions (Fig. 1), which is in contrast with images and advertisements from the period and which historians of dairywomen actively and continuously attempt to bring to light. Information concerning the amount of work and the type of work required to adequately complete dairy tasks is available and accessible. An understanding of the process of work and the proper use of dairy tools, as well as the overall way in which dairywomen worked, can avoid Campbell’s perceived danger that the ideal image of the dairyqueen could be mistaken for the reality of the milkmaid.

27 If so incongruous with real dairy work and dairywomen’s lives, why did advertisers utilize idealized dairyqueen images to promote dairy machinery? The dairy pin-up girl was constructed and projected in such a way as to appeal to the aesthetic and sexual appetites of men while also appealing to farmwomen’s visual and stylistic senses, selling the idea of women’s dairy work as pristine and simplified by machinery. These advertisements peddled a product that could potentially bring profit to the farmer, and labour management to the wife: a powerful combination that certainly went far in making this type of pin-up-girl advertising in dairy technology so pervasive.

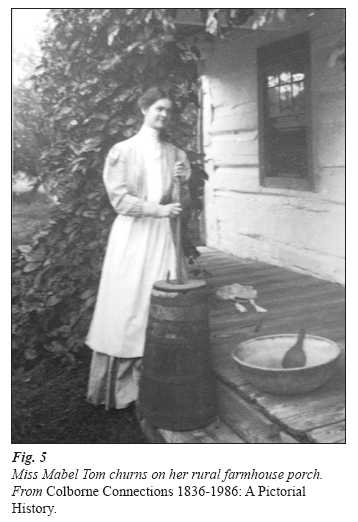

28 In a 1906 representation, Miss Mabel Tom dressed in her finest to churn with an upright dasher churn, while her bowl and paddle await to work the fresh butter (Fig. 5). In the picture, the dairyqueen churns on a tidy, vine-covered farmhouse porch. The white-washed dwelling creates a pastoral scene, with the backdrop appearing prosperous, long-settled and well-maintained. The overall dairyqueen image presented associates easily and clearly with Lears’s fecundity and abundance concept, linked with nostalgia and maternalism in advertising: a beautiful young woman churning at her home appears peaceful and productive in her rural setting. Appearance-wise, her hair is tidily drawn away from her face and she wears a hygienic white apron. Although her bonnet does not cover her hair, it is perfectly laid-out on the porch beside her. She smiles, appears at ease, keeps her apron pristine and serenely completes her chore. Despite appearances, however, this dairyqueen would have “dashed” up and down for approximately twenty to forty minutes, certainly producing some perspiration on her part. Subsequently, working, washing and salting the freshly-churned butter in the bowl, either between her knees or on her hip, would have consumed part of her day and much of her upper-body strength. While stereotypical notions of the rural farmwoman are evidenced in this dairyqueen image, none of the strain or effort required to complete the weekly and sometimes daily chore of butter-making is conveyed. An analysis of 19th- and early-20th-century advertisements for dairy technology demonstrates the dairyqueen ideal might have been difficult for any woman to achieve, let alone a hard-working farmwoman.

29 Within dairyqueen images, rigidly conventionalized standards for beauty became ensconced and were aimed at the rural housewife or farmwife. These standards involved: being fashionable while maintaining a budget; being organized and neat in appearance; being healthy—meaning slim and shapely with clear skin; and as working—with a pristine apron, clothing, and equipment—hygienically and thereby profitably. Not only did these dairyqueen images confront the milkmaid, but published “advice” reinforced the dairyqueen package, advising the milkmaid to look her best while completing her difficult daily chores. The “fashion note” below, excerpted from an 1893 edition of The Farmer’s Advocate, encouraged women to take more care with their appearance and reinforced common ideas of beauty and fashion standards for farmwomen: The fashions for women and girls were never more comfortable nor sensible than they are now. So many styles of hats and bonnets, so many shades of color; in fact, something to suit any face, complexion or purse. Fur is much worn….There is no particular fashion for wearing the hair; bangs are worn just as much as ever, and every woman has the good taste to wear her hair in the most becoming way. …and usually the hair is coiled or braided close to the head. Let us hope it may be years again before that untidy style of locks down the back, or flying curls or ringlets, will be worn. All is taut, smooth and neat. (Fashion Notes 1893)

30 A clear emphasis on thrift, neatness and simplicity in hair and attire, characterized the proffered style advice of the time. A “Sermonette” or recommentation from the 1895 edition of The Farmer’s Advocate also illustrates a clear emphasis on appearance and dress for farmwomen, albeit in a slightly more elaborate fashion than two years previously:We all know how some women, after a year of two of married life, get careless about their dress…. They seem to think that their fortune is made, and it isn’t necessary to arrange her hair becomingly and put on a pretty gown just for their husbands. This is all wrong, and it is an error that arises from laziness. Men like to see their wives look pretty just as much as they did when they were sweethearts. Endeavor to have daintily-arranged hair, and a neat and simple costume for breakfast. Go in largely for laces. A man is very fond of frills; bits of white about the neck and wrists always appeal strongly to him. (1895: 464)The above advice was printed in a widely distributed agricultural journal and certainly held a farm-wife audience. Even at an early morning hour, the dress and appearance expectations for milkmaids remained high. Impractical for everyday farm attire, lace and frills at the neck and wrists came recommended for fashionable farmwomen. Milkmaids on the Canadian dairy farm read these types of fashion articles. Just as few had access to the advertised technologies, few Ontario farm-women would have had ready access to varying styles of hats or variously-coloured fabrics. Ontario dairywomen regularly made their own clothes during this period and likely lacked exposure to the new and ever-changing fashions, except perhaps through patterned material, which might turn up in local shops, or through catalogues, agricultural journals or magazines. These “advice” articles in farm journals would have kept farmwomen abreast of fashion, even if they could not attain the printed dress or desired hair-do.

Fig. 6 (Left) “Standard” Cream Separator Company Poster from the Ontario-based Renfrew Machinery Company. Courtesy of the Canada Science and Technology Museum, Ottawa.

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 7

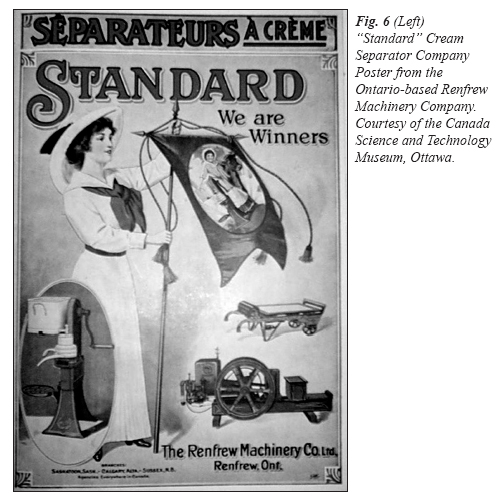

31 The dairyqueen and the iconography most often associated with her were the integral and central focus of dairy-technology ads and images, as opposed to the advertised tools themselves. Making idealized dairyqueens the focus of advertising, rather than the technologies, indicates that advertisers understood that women used the machines and “nagged” their husbands to purchase them, all the while knowing that men chose to purchase them, or not, thereby tailoring the advertisements to appeal to both genders. A subtle yet excellent example of this type of encouragement—for dairywomen to desire technological advancement—comes from a popular advertisement from the Ontario-based, Renfrew Machinery Company.

32 The play on words in this early Ontario advertisement is obvious, with a beautiful young woman holding a flag, or standard, advertising the newest Standard Company cream separator (Fig. 6). The secondary message is clearly discernible through the attire of the more prominent woman. As it was in England, the colour white was associated with the feminist fight for the franchise in Ontario. For dairywomen to campaign for women’s emancipation from dairy work, through the purchase of new technologies, is the message this advertisement expresses. Although the woman in the image is not wearing typical dairyqueen attire—she is dressed as a suffragette—the flag she holds presents a dairy-queen, her cow and her Standard separator. The dairyqueen on the flag is dressed in the orthodox dairy uniform: white bib-apron, white bonnet and all smiles. The gender-specific, politicized costume of the 19th-century suffragist not only indicated hygiene in terms of agricultural practice, but implied farmwomen “campaign” for better dairy equipment. Displaying both dairyqueens in white additionally implies there was likely little effort required to use the machine if the operator did not even soil their garments. The suffragette and dairyqueen are smiling and pretty, but neither is actually employing a cream separator. The slogan “We are Winners” calls to downtrodden and overworked dairywomen to march for better dairy equipment.

33 Barn work and dairy chores for the Ontario milkmaid meant dirty, smelly, time-consuming and difficult physical labour. Farming journals and advertising iconography constructed an idealized image of dairyqueens and farm work, reinforced through dairy pin-up ads for agricultural machinery, as well as female-oriented articles that discussed fashion and style. Dairyqueen images, in conjunction with published “style” advice, broadcast messages to farmwomen concerning appearance and work. The dairyqueen image, while it appealed in a sexualized manner to male buyers, appealed to milkmaids in a different manner. The beauty and cleanliness of the portrayed dairyqueens’ manifestation and work, however, offered false hope to Ontario dairywomen. As farms became better established and herds grew, the resultant increase in milk production meant increased labour for the Ontario milkmaid. Farmers, however, purchased little for the dairying process as long as the work remained female dominated. The result was the perpetuation not only of the treadmill-like drudgery of work for farmwomen, but also of the divide between the Ontario milkmaid’s day and the dairyqueen paradigm.

34 Instead of dairy work becoming easier through the introduction of technologies, farmwomen found their workload increased, their autonomy within dairying decreased and investment into dairying or dairy mechanization continually lacking. Despite some improvements to existing dairy tools, little technological or mechanized advancement arrived on the family farm to improve Ontario dairy-women’s lot. Meanwhile, dairying and its related chores were perpetuated as predominantly female, unmechanized and devalued work in Ontario.

35 With the development of agricultural technology, dairy advertisements projected an idealized dairyqueen image, targeting both farmers and farmwomen. Advertisers created a stereotypical iconography; smiling alluringly from ads and collectable surfaces, the dairyqueen appeared always young, beautiful and pristinely dressed, making farm work seem easy, especially with the help of the advertised dairy tool (Fig. 7). Lynn Campbell warned of the methodological challenge of interpreting and understanding images of rural Ontario, but farmwomen’s own words and the objects they use provide insight into the late 19th- and 20th-century Ontario dairywomen’s overwhelmingly difficult working lives. Material culture, in combination with more traditional primary sources, indicates the disparity between the experienced milkmaid and the idealized dairyqueen, as well as an indication of the underlying devaluation of Ontario dairywomen’s work.

References

A Friend to Farmer’s Wives. 1897. The Farmer’s Advocate 32 (6): 282.

A Sermonette for Wives. 1895. The Farmer’s Advocate 30 (11): 464.

Barlow, Ronald S. 2003. 300 Years of Farm Implements and Machinery 1630-1930. Iola, WI: Krause.

Bennett, Sue and Lynn Campbell. 1986. Rural Women, Labour and Leisure: 1830s to 1980s. Milton: Ontario Agricultural Museum (unpublished).

Benoit, Robert, Sam Stephens, and Michael Fournier, eds. 2000. DeLaval, Sharples, and Others: Cream Separator Memorabilia. Self-published: Quebec.

Blandford, Percy. 1976. Old Farm Tools and Machinery: An Illustrated History. Fort Lauderdale: Gale Research Co.

Brown, Jonathan. 1989. Farm Machinery, 1750-1945. London: B. T. Batsford.

Campbell, S. Lynn. 1988. R. R. Sallows Landscape and Portrait Photographer. Milton: Ontario Agricultural Museum (unpublished).

Cohen, Daniel. 1982. The Last Hundred Years, Household Technology. New York: M. Evans.

Cohen, Marjorie Griffin. 1988. Women’s Work, Markets, and Economic Development in 19th-Century Ontario. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Cowan, Ruth Schwartz. 1983. More Work for Mother: The Ironies of Household Technology from the Open Hearth to the Microwave. New York: Basic Books.

———. 1997. A Social History of American Technology. New York: Oxford University Press.

Errington, Elizabeth Jane. 1995. Wives and Mothers, School-mistresses and Scullery Maids, Working Women in Upper Canada, 1790-1840. Montreal: McGill Queen’s University Press.

Fern, Fanny. 1868. Fanny Fern on Farmer’s Wives. The Farmer’s Advocate 3:19.

Fashion Notes. 1893. The Farmer’s Advocate 28 (1): 35.

Halpern, Monda. 2001. And On That Farm He Had a Wife. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Hazlitt, Shirley. 1986. Colborne Connections 1836-1986: A Pictorial History: Featuring Photographs of R. R. Sallows and Others. Goderich, ON: Township of Colborne.

Hubka, Thomas C. 1984. Big House, Little House, Back House, Barn, The Connected Farm Buildings of New England. Lebanon, NH.: University Press of New England.

Jensen, Joan M. 1986. Loosening the Bonds: Mid-Atlantic Farm Women, 1750-1850. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

———. 1988. Butter Making and Economic Development in Mid-Atlantic America from 1750 to 1850. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 13(4): 813-29.

Juster, Norton. 1996. A Woman’s Place, Yesterday’s Women in Rural America. Colorado: Fulcrum Publishing.

Kline, Ronald R. 1997. Ideology and Social Surveys: Reinterpreting the Effects of “Laborsaving” Technology on American Farm Women. Technology and Culture 38 (2): 355-85.

Lears, Jackson. 1994. Fables of Abundance, A Cultural History of Advertising in America. New York: Basic Books.

McMurry, Sally. 1988. Families and Farmhouses in 19th-Century America: Vernacular Design and Social Change. New York: Oxford University Press.

McNerney, Kathryn. 1991. Kitchen Antiques, 1790-1940. Paducah, Kentucky: Collector Books.

Osterud, Nancy Grey. 1991. Bonds of Community, The Lives of Farm Women in Nineteenth-Century New York. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Parr, Joy. 1999. Domestic Goods: The Material, the Moral and the Economic in the Postwar Years. Toronto: University Press.

Seymour, John. 1987. The National Trust Book of Forgotten Household Crafts. London: Dorling Kindersley Limited.

Shortall, Sally. 1999. Women and Farming: Property and Power. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Willard, A. 1877. Willard’s Practical Dairy Husbandry. New York: Excelsior Publishing House.

Notes