Liminal Spaces in the Museum of London:

The Great Fire Experience1

Lynn MatteMemorial University of Newfoundland

Producer/sponsor: Museum of London

Venue: Museum of London

Curator: Philippa Glanville

Permanent exhibit

1 In early September 1666, the city of London was forever changed. The majority of structures in the city were built of timber and fire was a part of the rhythms of the city, but on this particular occasion conditions, as well as perhaps the actions or inaction of certain groups of people, resulted in a fire that burned for several days. The homes of one-sixth of the population were lost, as were numerous religious and civil structures (Ellis 1976, 8). The Museum of London houses an exhibit about the fire—The Great Fire—and another that focuses on the rebuilding of the city. Linked to The Great Fire Experience exhibit are three interactive programs about the fire that are offered for school children. An information pack about the museum website is also available.

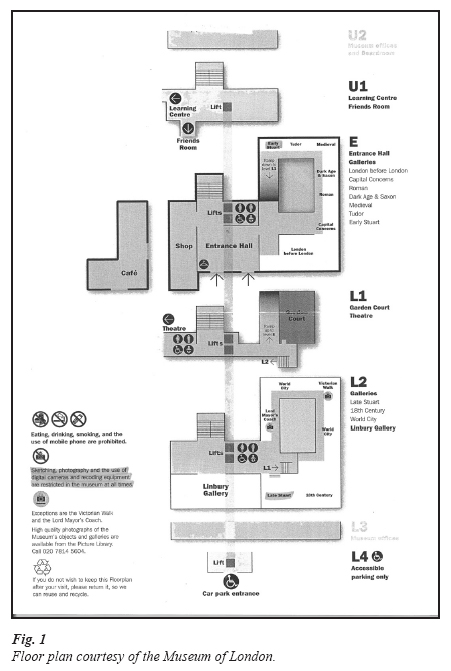

2 The Museum of London is divided into two levels. Although the building appears circular from the exterior, the entrance and lower level are roughly box-shaped with an open garden court in the center. The garden court is surrounded on all four sides by glass walls. The Great Fire Experience is a permanent exhibit that was created in the early 1970s that is used to transition visitors between pre- and post-fire London, between Medieval life and the Enlightened age that followed, and between two floors of the building (Fig. 1). The Museum of London was opened in 1976 and is the result of the amalgamation of the collections of the former London Museum and the London Guildhall Museum.

3 The Museum of London’s exhibits are arranged in chronological order leading the visitor from the London of Roman times to the present day. The Great Fire Experience occupies a liminal space in that timeline; it occurs at the end of the “dark ages,” on the cusp of the Enlightenment. The exhibit is located in the Early Stuart Gallery which is on the entrance level of the museum. The Early Stuart Gallery covers the period from 1603 to 1666. This examination of the Museum of London’s Great Fire Experience exhibit draws on the museum’s mandate and on a number of theories that explore the messages the exhibit presents. These relate to the identity of the city and its people, the function the exhibit serves within the museum’s 21st-century context and the semiotics of the objects on display, as well as their relationship to surrounding objects. Although the exhibit is meant to be historical, it provides greater insight into the social and political concerns of those who created the display than of the people who lived at the time of the Great Fire.

4 Museums are human institutions for learning and forums for representing the past. They collect, care for, research and display artifacts so as to provide museum visitors with a new understanding of the culture from which the displayed objects originate. Perhaps less obviously, the museum also provides a forum for learning about the society that has put together the exhibits and displays. How objects are displayed, and what information is provided, can also shed light on the political or social aims of the funding body of the museum.

5 The Museum of London’s annual report from 2003-2004 states:The Museum of London’s mission is To Inspire A Passion For LondonBy communicating London’s history, archaeology and contemporary culture to a wider world.By reaching all of London’s communities through being London’s memory: collecting, exhibiting, investigating and making accessible London’s culture through discovering and chronicling London’s stories and interpreting them in an educative, entertaining and vibrant manner through explaining and recording change in contemporary London.By playing a role in the debate about London, facilitating and contributing to Londonwide culture and educational networks.By developing a professional and specialist expertise about London in our staff. (Museum of London 2004)The museum’s mission statement can be used to gauge the success of The Great Fire Experience exhibit.

Fig. 1 Floor plan courtesy of the Museum of London.

Display large image of Figure 1

6 As an historical exhibit, the Great Fire of London has the ability to shape or re-shape public memory and revise interpretations of the past (Davison 2005, 184). Davison notes that “[m]useums, like memory, mediate the past, present and future … give material form to authorized versions of the past … [and] anchor official memory” (186). Her argument raises interesting questions to be asked of an historical museum exhibit. The Great Fire Experience is in a museum that has a mandate to “inspire a passion for London.” While the museum does include a large 17th century anti-Catholic plaque that blames papists for the 1666 fire, the exhibit does not include any text to explain how pervasive the religious tensions of the time were.

7 The Great Fire Experience exhibit was created under the guidance of then curator, Philippa Glanville. It displays fragments from buildings, several 17th-century leather buckets, firemen’s hats, a few tobacco pipes and pipe fragments that survived the fire, as well as an audio-visual recreation of the city in flames. It also incorporates historical documentation of the Great Fire including excerpts from the Diary of Samuel Pepys (1972). A native Londoner, Pepys worked as a senior naval administrator. His diary documents detailed descriptions of the progress of the fire and records some of the rumours that were spread relating to the cause of the conflagration (267-82). Other manuscripts describing the event survive, but Pepys’s diary offers more insight into the daily workings of the city—from a middle class perspective—over several years. The use of Pepys’s account is somewhat problematic; it undoubtedly lends a sense of authenticity to The Great Fire Experience, but throughout the exhibit the words are never attributed to Pepys.

8 Books about the Great Fire abound. The most pressing question in the various accounts is tied to what and who caused the fire. The accounts I read mention a French Catholic man who was executed after confessing to setting fire to the house of the baker, Thomas Farynor. All accounts question the veracity of the man’s confession and leave the reader to make the decision about how the fire actually began.2 Documents from the period lay the blame on a variety of people and groups including the Dutch, the French Catholics (Hanson 2002, 180) and the wrath of God (Tinniswood 2004, 147-48). The Crown released a proclamation with its own interpretation of the cause of the blaze:The king’s “proclamation” both invokes and sanctions another interpretation of the fire’s cause, one that attributed God’s wrath to a generalized sinfulness among the people—an interpretation that, during earlier fires, had been traditionalized among the people…. As a political maneuver, King Charles II’s proclamation was meant, on one level, to draw the people together in order to work through a commonly shared catastrophe, but, on another level, its purpose seems to have been to deflect attention away from interpretations that might threaten the authority of his right to rule. (Preston 1995, 39-40)Interestingly, the exhibit does not delve into the contemporary or earlier concern with the cause of the fire. Instead a panel simply notes that it began in Thomas Farynor’s bakery. Controversy about the cause of the fire has captivated the interest of many people over several hundred years, yet the exhibit has been designed to all but avoid the topic.

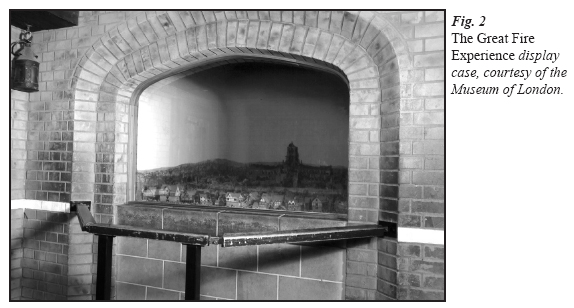

9 The fire devastated the city as no other fire in London’s history. The duration and extent of the blaze has been attributed to a number of aggravating factors: arsonists spreading the blaze (Tinniswood, 58), strong winds, a poorly organized fire-fighting system, lack of effective fire fighting equipment (52), poor city planning that resulted in overcrowding, the use of flammable building materials and inaction on the part of citizens who were too busy to help fight the fire because of their concern to protect their personal belongings. Laws making it difficult to tear down houses in order to create firebreaks was also a contributing factor (Ellis 1976, 28). The fire created a distinct change in the appearance of the city and the exhibit is a point of reference for exploring pre- and post-fire architecture and city design.

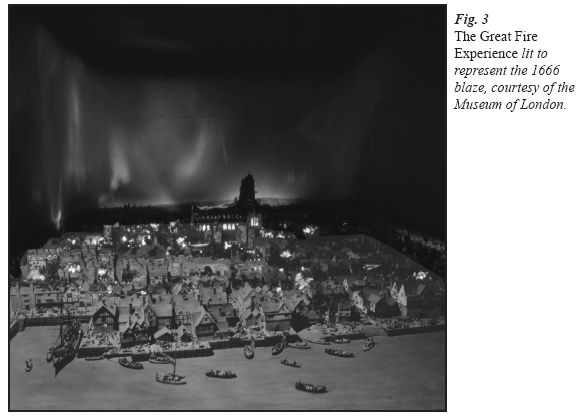

10 The number of foreign residents in 17th-century London is open to debate. England was on less than good terms with several neighbouring nations, yet the foreign population of the capital city is estimated to be in the thousands (Tinniswood, 59). How the exhibit presents the assignment of blame for the fire affects how the visitor is meant to view the inhabitants of the city, and the citizens’ level of cultural tolerance. The exhibit avoids entering the debate on the cause of the blaze by simply stating that it began in a bakery. Has the museum purposely not addressed the assignment of blame because to do so would highlight how factious the 17th-century population of London was? If this is the case, is it purposely avoided so as not to draw attention to social divisions of the residents of present-day London, thereby exposing how little the human side of the city has changed regardless of its many cosmetic reincarnations? Avoiding this part of the history of the Great Fire is a reflection of present-day concerns with equal rights and the avoidance of discrimination based on factors such as race, religion or gender.

11 Constructions of identity are tied to one’s history. Museums or, on a smaller scale, exhibits are “resource[s] for local people in ‘understanding their history’” (MacDonald 2005, 277). They present images of identity to those they purport to represent, as well as to outsiders. The Museum of London incorporates esoteric information into its exhibit by drawing on private documentation dating from, and relating specifically to, the Great Fire. An analysis of how the museum has chosen to portray 17th-century Londoners may offer insight into how present-day Londoners see themselves and wish to be viewed by outsiders. How one reacts to crisis and adversity can be viewed as an opportunity to reflect on one’s true character; how has the character of individual Londoners, and as Londoners on the whole, been presented in this crisis situation? Since the exhibit avoids the issue of whether the blaze was intentionally set, and by whom, the visitor is left merely with a sense of sympathy for all those affected by the conflagration and no understanding of the controversy that ensued.

12 Michael Rowlands argues that “much faith is put at present in the transforming qualities of both museum and heritage cultures. By being able to assert the right to have a culture and identity, re-engaging with the past is claimed to be not just a matter of re-call but to have a more curative role” (Rowlands 2002, 112). He is suggesting that being able to claim possession of cultural heritage makes that heritage a reality, gives it tangibility that as such demands respect and has rights. Having one’s heritage represented in a museum gives the concept of culture a physical form that has been preserved and displayed for all to see. This argument supports William Bascom’s concept of the four functions of folklore. According to Bascom, folklore validates culture, educates, amuses and maintains conformity to accepted patterns of behaviour (Bascom 1965, 291-94). The Great Fire exhibit is used to educate and amuse while validating culture. Although the exhibit focuses on an event that occurred in 1666, the culture being validated is that of 20th-century London, a culture that in part owes its existence to events such as the Great Fire.

13 Another approach to exploring and analyzing The Great Fire Experience exhibit is from the perspective of semiotics. Stephen Harold Riggins discusses the semiotics of material culture and lists categories for exploring individual objects as well as their relationships to the objects around them in his article “Fieldwork in the Living Room: An Autoethnographic Essay” (1994). The application of Riggins method to the exhibit, and to the artifacts that constitute it, may contribute to deeper insights into 17th-century London, and to the 20th-century London in which the exhibit was created. What, for example, do the objects selected for the exhibit and their relationship to each other, tell us—if anything—about how museum staff view London and Londoners of the 17th century?

14 As a system of analysis, structuralism “focuses on the relationships that exist among elements in a system instead of on the elements themselves” (Berger 1995, 97). While objects tell us much about the culture in which they originate, they can offer different messages when placed in different contexts (98). The objects collected and displayed by a museum still retain the cultural messages tied to their former lives outside the museum, but they also carry new messages as a result of their museum context. As an institution, the museum is viewed as an authoritative voice on what is valuable and, in this case, what is historically valuable. The inclusion or exclusion of specific groups of people and their history acknowledges or denies the worth of those groups. The Great Fire affected all levels of people living in the city, from the very wealthy to the very poor. It also devastated the city’s infrastructure and demolished large sections of its commercial and business districts. By examining the depth of the exhibit’s portrayal of different social groups one might discern how we are meant to envision pre-fire London, its layout, architecture, demographics, cultural dispersion and interaction, its legislation and political importance.

15 The Great Fire of London, although highly controversial in its day, fails to ellicit such strong emotional responses nearly 350 years after the fact. According to written sources, Pepys among them, the loss of four-fifths of the city to flames in less than a week caused all manner of cultural and political tensions and accusations. The Museum of London is meant to be “London’s memory,” but it is also mandated to inspire a passion for the city and this assertion reaches the heart of how museums are able to affect societal perceptions of the past. The Great Fire was a huge event in the history of London. The fire presents an opportunity to discuss xenophobic concerns, religious intolerance and beliefs, class struggle, societal values such as safety precautions and neighbourly behaviour, building esthetics, the distribution of population and the use of space in a post-medieval urban context. Romanticized depictions of the fire describe pre-fire London as a cramped and dirty cesspool of a city while post-fire London is cleaner, lighter and healthier, thanks to the glories of superior city planning and architecture, including the work of Sir Christopher Wren and his contemporaries. The Museum of London’s presentation of the Great Fire of 1666 is cursory. The main function of the exhibit is as a transition between its medieval incarnation and the Renaissance rebuilding of the city. The Great Fire Experience exhibit is tied to the Rebuilding of London exhibit on the floor below through the theme of firefighting in the city. The firefighting methods and implements of pre- and post-1666 fire are prominently displayed near both exhibits.

16 Although the fire could have been used to discuss a number of the topical issues of 17th-century London, the museum chose not to incorporate such matters into its exhibit. Easily accessible historical material about how the fire was started and who was blamed for causing it is not mentioned in the exhibit. There is no reference to tensions between the English and the French and Dutch. Anti-Catholic propaganda is on display in the rebuilding section of the Late Stuart Gallery, but there is no information panel to elaborate on why the propaganda was attached to the monument erected in memory of the 1666 fire. Several themes link the exhibit just prior to The Great Fire Experience to the Rebuilding of London exhibit in the Late Stuart Gallery.

17 The Great Fire Experience exhibit is permanent and none of the objects are rotated. A central piece of the exhibit is a fire model donated by John George Joicey.3 The Great Fire Experience appears to be the title that specifically refers to an automated diorama of 17th-century London in flames. The display is motion-activated as guests enter the viewing booth. Once the detector has been set off a female voice announces that The Great Fire Experience will commence shortly so that any other guests in the vicinity who are interested may hurry into the small theatre. The space is a tiny rectangle measuring approximately two by 1.5 metres. The visual focus is on a miniature model of medieval London that is protected behind plexiglass. A rail ensures that guests cannot stand directly in front of the glass, thereby allowing all present to see the diorama (Fig. 2). The lights in the space dim as wind and tolling bells are heard; the effect is ominous. A male voice begins to speak, telling guests of his experience of the fire. Although visitors are not made aware of it, the speaker is meant to be Samuel Pepys recording the progress of the fire.

Fig. 2 The Great Fire Experience display case, courtesy of the Museum of London.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 3

18 As Pepys’ narrative progresses, the image of the darkened city begins to brighten as more and more houses are burned. Red and yellow lights on areas of the model simulate flames (Fig. 3). The River Thames and St. Paul’s Cathedral are two easily discernable landmarks on the model. On the wall behind the model, lighting effects create the appearance of dancing flames as London is reduced to the contents of Pepys’s diary. As the fire rages, sound effects add strength to the sound of the wind and to the narrator’s voice, including the crackling and popping of burning timbers. Explosions coincide with narration that describes the creation of firebreaks. Then, all is quiet and dark. After experiencing the terror of the city in flames, there is a pause that is followed by a second male narrator who informs the audience of the extent of the fire damage, that it devastated London and left many homeless. Guests exit through a separate, curtained doorway so as not to set off the motion detector on the way out. Of those I saw enter the theatre, all were adults; many did not sit through the entire experience and I wondered if the fact that the speaking voice is not contextualized contributed to the early departures.

Fig. 4 Diagram of the floor area surrounding The Great Fire Experience.

Display large image of Figure 4

19 Just before the entrance to the diorama a wall panel enumerates “The hazards of city life” in the period and includes a paragraph on fire:Fires were a permanent hazard of London life. Most buildings were basically of timber, the houses were closely packed together and the streets were narrow. The aldermen of each city ward were required to provide buckets, hand squirts for firefighting, and hooks to pull down smouldering thatch. A severe fire in 1533 destroyed a block of buildings in the north end of London Bridge. When they were rebuilt a gap was left, to provide a fire-break. In 1666 this prevented the Great Fire from spreading into Southwark.Beyond this panel is the entrance to the diorama and on the wall facing the entrance is a map of London prior to the fire with landmarks—mainly churches and a few theatres—labelled. There is one more piece of text that prepares patrons for The Great Fire Experience. It is located on the door frame of the diorama entranceway. The sign reads:The Great Fire of 1666: On 2 September 1666 a disastrous fire broke out in Pudding Lane near London Bridge. Tuesday 4 September was the worst day when Cheapside, Guildhall and St. Paul’s were destroyed and the fire reached the Temple. On 6 September it was halted to the west at Fetter Lane and Smithfield, and to the east at All Hallows Barking. In four days it destroyed four-fifths of the City.The background wall colour in this hallway of the Early Stuart Gallery is green. When you reach the entrance to The Great Fire Experience the colour dramatically changes to a rich shade of red. The above text is located to the right of the theatre entranceway. To the left is a painting of the conflagration from ca.1675 entitled “The Great Fire of London, 1666.” Central to the piece is St. Paul’s in flames. In the foreground and to the left is an image of Ludgate aflame and people fleeing the city with whatever they can carry. To the right the charred ruins of St. Anne’s church is one of the few objects in the work that is not in flames.

20 After exiting through a red velvet curtain, visitors directly face a steward station. The stewards I observed were alternately seated on the chair provided for them or they were strolling along the corridor that flanks the garden court. Upon exiting the theatre, the space is small and connects to the ramp for the lower level and the Late Stuart Gallery only a few steps beyond the theatre. The steward’s seat is located in a small dead-end area that overlooks the ramp to the lower level. When the steward is seated patrons are unable to examine two of the paintings of the Great Fire that are hung on the walls behind and beside the steward’s chair. Just before the steward’s station, on the wall to the right as one exits the theatre, is a two metre glass-fronted case that is recessed into the red-painted wall.

21 To the right of the case an information panel entitled “Evidence of the Great Fire” explains that the encased objects are 17th-century artifacts that the museum has designated as representative of the Great Fire. Among the items are a selection of clay pipes, two leather water buckets and one fragment, barrel fragments such as hoops made of oak and chestnut, bricks from a cellar in Pudding Lane and a leather helmet that resembles modern firefighters’ hats. The helmet has some initials and numbers on it that link the object to the parish of St. Botolph and St. George Billingsgate. This display is extremely interesting but is located in a position that makes it difficult for visitors to access. Tucked into a corner between the theatre exit and the steward’s station, the space is cramped and awkward. The objects in the case can only be examined by standing extremely close to it so as not to interfere with traffic exiting The Great Fire Experience theatre. The case is approximately two metres tall and .75 metres wide making it extremely difficult to view the objects on the upper or lower shelves while standing within a foot of the glass to avoid museum traffic.

22 There are several possible explanations for why the museum has chosen to present the Great Fire of 1666 in such a limited way. Hazel Forsyth, curator of the Early Stuart Gallery, explained that the museum obtained collections from two other institutions. Therefore, the current exhibit may simply be an amalgamation of displays from the museum’s two predecessors. Museum exhibits are costly and time-consuming to create and, as such, pre-existing exhibits would have to be made to fit into the space provided in the new facility. The museum is a history museum and it has chosen to mix both object-and idea-based displays to convey information about the Great Fire. Prior to the entrance of The Great Fire Experience exhibit are a number of information panels containing text and imagery. The diorama, the paintings and the artifact case are all very much object-based and have very little text connected directly with the objects.

23 The Great Fire of London is part of the national curriculum, and as a way of teaching children about this event school groups often use the museum. The learning department of the museum reports that the museum delivers programming for children aged 5-11 and for those aged 11-16. The three listed school programs are “London’s Burning,” “Fire! Fire!” and “The Great Fire.” The programs link learning about history to other areas of the curriculum such as art and design technology, literacy and storytelling. These programs connect The Great Fire Experience to information that is presented in the Later Stuart Gallery—specifically the rebuilding of London after the blaze. The school programs also address questions such as how the fire was started and put out, and introduce pupils to some of the people affected by the event such as King Charles II and Samuel Pepys.

24 The Museum of London has attempted to address the lack of information provided by its displays through the museum’s website. Under the heading “The Great Fire of London: day by day” internet users can access a detailed timeline of the progress of the fire from the day prior (September 1) until after the blaze was finally put out (September 7). A list of the results of the fire follows and readers are encouraged to visit The Great Fire Experience and the Late Stuart Gallery. A second fact pack is entitled “Investigate The Great Fire of London.” This web publication asks and answers questions such as Who were the victims? Why was the damage so bad? and Who was to blame? These information packs are listed on the website as information for teachers, but they can be printed off by anyone visiting the page. They are extremely useful for any visitor to the Fire exhibit. The packs are prepared by the Museum of London’s Interpretation Unit and both date from 2002. Dean (1994) writes that research into effective museum displays has shown that people have three principal means of gathering information:

- Words – language, both heard and read, requires the most effort and mental processing to extract meaning.

- Sensations – taste, touch, smell, hearing are more immediate and associative.

- Images – visual stimulus is the strongest, most memorable of the methods. (Dean, 26)

The Great Fire Experience capitalizes on the image and sensation responses of museum guests by presenting the fire of 1666 as a diorama. Sight and sound are used to make visitors feel as though they are actually witnessing the burning of the city. Words have also been incorporated in an attempt to explain what the visitors are seeing and hearing. Many who visit museums skip over text panels and focus on the objects and images that are displayed. Although I personally felt that the fire exhibit did not contain enough information, there is probably more text associated with the display than the majority of museum patrons will ever read. The museum has compromised on this issue by capitalizing its use of space and not including a great deal of text, while still providing fact packs for those who may want to know more about the event. The fact packs include small bibliographies for those interested in reading further about a particular event or topic. The museum is meant to educate through the display of objects and it has rightly chosen to provide only the most necessary textual information about its collections while directing interested patrons to the available written sources. The museum not only recommends, but also publishes and sells, a wide range of books that deal specifically with the history of the city of London as well as the museum’s exhibitions.

25 The Late Stuart Gallery, found on the level below, begins with he rebuilding of the city after the fire. The museum website states that “under the guidance of Sir Christopher Wren, a new ‘modern’ city was built on the ashes of the Great Fire. In [the] gallery you can study original maps that show the extent of fire damage or describe plans for rebuilding.”4 Although the Late Stuart exhibit is separate from that of the fire, knowledge of the fire is important to understanding the changes taking place in the city in the late 17th century. The message of The Great Fire Experience is that London rises like a phoenix from the ashes of its former self to be triumphantly reborn. The darkly wooded, lowceilinged Early Stuart interiors that precede The Great Fire Experience are juxtaposed against the more open, lighter and more ornately decorated artifacts of post-fire, Late Stuart London. Just as the monarchy was overthrown and then recreated to suit the changing needs of the country, the devastation of the Great Fire of 1666 facilitated the evolution of London’s cityscape.

26 A visit to the Late Stuart Gallery shows visitors how the Great Fire affected the city of London. A number of proposed city plans are displayed as well as a map that shows how extensive the fire damage was. This map directly contrasts to the map of pre-fire London on display near The Great Fire Experience. Another direct contrast is the display that deals with building regulations, fire code, fire fighting and prevention methods that were either reinforced or newly introduced as a result of the fire. Some of the objects on display include a hand squirt and the tub of a fire engine; both date from the 1670s.

27 One of the first objects to greet people as they enter the Late Stuart Gallery is a large engraved plaque that has been split roughly down the middle. The plaque is the only object that reflects some of the cultural tensions going on in the city and intimates that the fire may have had malicious beginnings rather than being started accidentally. The plaque reads:Here by ye permission of heaven, hell broke loose upon this Protestant city from the malicious hearts of barbarous papists by ye hand of their agent Hubert who confessed, and on ye ruins of this place declared the fact, for which he was hanged, (vizt) that here began that dreadfull [sic] fire, which is described and perpetuated on and by the neighbouring pillar.Above the plaque is a photograph of Christopher Wren and Robert Hooke’s Monument to the Great Fire of 1666. The plaque reflects the need to assign blame for the devastation. Although the Dutch, French and Irish were all suspected of being involved in the blaze, the blame finally landed on the French because a Frenchman confessed to having started the fire. The text of the plaque reflects its original location near the monumental pillar and, while the monument still stands, the presence of the plaque in the museum speaks volumes about the changing perceptions of the causes of the fire and the attitudes of Londoners toward other cultural groups. Rather than focusing on the negative aspects of the blaze—such as the cultural, religious and class tensions—the museum presents the fire as a horrible accident that led to the rebuilding of the city and made way for some of the city’s most famous architecture, such as Wren’s St. Paul’s Cathedral. Other improvements that resulted from the fire include home insurance (for brick structures) and better organization of fire fighting resources.

28 The English are proud of their heritage and spend a great deal of money preserving historical buildings. The Great Fire exhibit explains why it is rare to see timber-frame structures, or any other buildings, pre-dating the 17th century in London. Fragments of pre-fire buildings, including column capitals from the gothic St. Paul’s Cathedral, are mixed in with the panels in the Late Stuart Gallery that describe the rebuilding of the city.

29 Neither pre- nor post-fire London is given a negative image by the museum displays. Post-fire London is presented as being more organized and having learned from the mistakes of the overcrowded and plague-ridden medieval city, but it is done in a way that suggests that these changes were part of a natural progression as technology and science made advances. Little of the contemporary understanding of the cause of the blaze is presented; instead visitors are given a 20th-century interpretation of a 17th-century event. The focus of these two exhibits is on the architecture, the shape and look of the city of London, rather than on the people who were the life of the city.

30 The Fire is treated as a segue between two disparate faces of the city. As such, exhibits dealing with the blaze and the rebuilding of London as a consequence occupy the transitional space between the two floors of the museum, using the space of the museum to denote a break in the physical make-up of the city. Although it was a disaster of enormous proportions, the number of people who died as a direct result was quite low—though many more later perished due to lack of food and shelter. The museum has not chosen to focus on the human suffering nor on the massive losses people suffered, but rather has focused on the continuation of life in the city even in the face of such a horrible tragedy. Londoners suffered but they chose to rebuild their lives and their city. The city was not unified in its attempts to stop the fire. A sense of unity, however, is associated with the concerted efforts to reconstruct homes and livelihoods in England’s capital in the aftermath of the fire.

31 The Great Fire Experience is a popular exhibit in the Museum of London and is regularly visited by school and tour groups. The exhibit relies on sensations and images to transmit its message about the importance of the event within the history of the city. Unfortunately, not enough words have been used to properly contextualize the effect the fire had on the population of the city. Visitors are given not even a hint of the social and political tension surrounding the suspicions and accusations relating to the cause of the fire. Samuel Pepys is nowhere identified as the man who penned the words used in the diorama’s narrative of the fire. The location of the artifact display case and the paintings of the Great Fire could be improved to allow visitors to view the items without impeding the flow of museum traffic. The history of a city is incomplete when its buildings and physical make-up are documented without any information about the society that erected, used and, perhaps purposely, burned or tore down those same structures.

References

Bascom, William R. 1965. The Four Functions of Folklore. In The Study of Folklore, ed. Alan Dundes, 279-98. Engelwood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Berger, Arthur Asa.1995. Cultural Criticism: A Primer of Key Concepts. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Davison, Patricia. 2005. Museums and the Re-shaping of Memory. In Heritage, Museums and Galleries: An Introductory Reader, ed. Gerard Corsane, 184-99. London: Routledge.

Dean, David. 1994. Museum Exhibition: Theory and Practice. Routledge: London.

Ellis, Peter Beresford. 1976. The Great Fire of London: An Illustrated Account. Edinburgh: Thomas Litho.

Museum of London. 2004. Financial Statements for the year ended 31 March 2004 together with the Governors’ and Auditors’ reports. <http://www.museum oflondon.org.uk/MOLsite/aboutus/downloads/0304YearEndAccounts.pdf>.

Hanson, Neil. 2002. The Great Fire of London: In That Apocalyptic Year, 1666. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons.

Macdonald, Sharon. 2005. A People’s Story: Heritage, Identity and Authenticity. In Heritage, Museums and Galleries: An Introductory Reader, ed. Gerard Corsane, 272-90. London: Routledge.

Pepys, Samuel. 1972. The Diary of Samuel Pepys. Vol 7. Eds. William Armstrong, Emslie Macdonald et al. Trans. Robert Latham and William Matthews. Berkley: University of California Press.

Preston, Cathy Lynn. 1995. London’s Flames Revisited: Rumor-legend and the Negotiation of Political Agendas in 17th-century England. Contemporary Legend 5:38-75.

Riggins, Stephen Harold. 1994. Fieldwork in the Living Room: An Autoethnograhic Essay. In The Socialness of Things: Essays on the Socio-Semiotics of Objects, ed. Stephen Harold Riggins, 101-47. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Rowlands, Michael. 2002. Heritage and Cultural Property. In The Material Culture Reader, ed. Victor Buchli, 105-14. Oxford: Berg Publishers.

Sheppard, Francis. 1991. The Treasury of London’s Past. London: Hmso Books.

Tinniswood, Adrian. 2004. By Permission of Heaven: The True Story of the Great Fire of London. New York: Penguin.

Notes