Sir Frederick Gibberd and the Gibberd Garden on Marsh Lane, Old Harlow, Essex:

A Study of the Meaning of a Garden, Past, Present and Future

Cynthia BoydMemorial University of Newfoundland

Résumé

Sir Frederick Gibberd (1908-1984), architecte moderne ayant eu une reconnaissance internationale, était connu en particulier pour son travail en tant qu’architecte consultant à la planification de la nouvelle ville de Harlow, dans les années 1940. Tandis que son succès en tant qu’architecte était incontesté, sir Frederick a consacré d’innombrables heures à la création de son propre jardin à « Marsh Lane », dans les faubourgs du Vieux Harlow, dans le comté d’Essex en Grande-Bretagne. Selon plusieurs écrivains contemporains spécialistes des jardins, celui-ci est l’un des plus remarquables des jardins modernes anglais du XXe siècle. Cet article décrit le jardin de sir Frederick du point de vue de la théorie de la réception, car il relève à la fois de la manière dont les concepteurs des jardins et les visiteurs perçoivent et reçoivent les espaces des jardins. De plus, cet article reconnaît la signification du jardin en tant que lieu, idée, action et expérience. Le jardin de sir Frederick, que l’on appelle aujourd’hui Gibberd Garden, présente un style de jardin à la fois formel et informel ; de plus, dans le jardin est exposée une grande collection de sculptures classiques, contemporaines et modernes, soigneusement intégrées dans de nombreux parterres ou espaces compartimentés. Tandis que la sculpture joue un rôle essentiel dans l’atmosphère du jardin, des éléments enfantins tels qu’un château entouré de douves sont aussi amusants pour tous les âges. Actuellement, le Gibberd Garden est la propriété du Gibberd Garden Trust, et est géré par des bénévoles.Abstract

Sir Frederick Gibberd (1908-1984), an internationally known modern architect, was particularly recognized for his work as Consultant Architect Planner of Harlow New Town in the 1940s. While his success as an architect is beyond dispute, Sir Frederick devoted endless hours to the creation of his own garden at “Marsh Lane,” on the outskirts of Old Harlow, in the county of Essex, U.K. According to several contemporary garden writers, this garden is one of the most eminent English Modern gardens of the 20th century. This essay describes Sir Frederick’s garden from the perspective of reception theory as it pertains to how both garden designers and visitors perceive and receive garden spaces. In addition, this essay recognizes the meaning of gardens as place, idea, action and experience. Sir Frederick’s garden, now referred to as the Gibberd Garden, features both formal and informal garden styles; in addition, the garden showcases an extensive collection of classic, contemporary and modern sculptures carefully integrated within many garden rooms or compartments. While sculpture plays a leading role in the atmosphere of the garden, child-like elements such as a moated castle are equally amusing to all ages. The Gibberd Garden is currently owned and operated by the volunteer efforts of The Gibberd Garden Trust.1 The Gibberd Garden is a public garden located on the outskirts of Old Harlow, Essex, England. The garden includes features characteristic of formal and informal garden styles from the 18th through the 20th centuries. Originally owned by Sir Frederick Gibberd, who bought the 2.8 ha (7 acres) of land and the existing house in 1956, it is currently owned and operated by the Gibberd Garden Trust. Sir Frederick created a series of garden rooms and vistas on the property he once called Marsh Lane. Initially, Sir Frederick’s interest stemmed from his instrumental role as Consultant Architect Planner of Harlow New Town—a role that ultimately gained him international recognition as a modern architect. Notably, Sir Frederick’s other commissions included massive projects such as Liverpool’s Metropolitan Catholic Cathedral of Christ the King, Tryweryn and Derwent Reservoirs, Hinkley Point Nuclear Power Plant, Heathrow Airport and riverside walks through Leamington Spa (Boynton 1984, 30; Harling 1967, 4). His architectural contributions spanned the Atlantic as well. In the 1960s, Sir Frederick was approached by Lord Stephen Taylor, then President of Memorial University of Newfoundland, to create a master plan for Memorial that would allow for an increase in the student population from 4,500 to 12,000.1

Sir Frederick Gibberd: Beginnings and Architectural Influences

2 Sir Frederick was the oldest of five brothers in Coventry. Seeking escape from his siblings, he often went to his grandmother’s house, probably where he first learned to garden. His interest in architecture stems from once seeing the detailed plans of a house and making an immediate decision that he would become an architect. In the 1930s, Sir Frederick travelled to Italy where he discovered the architecture of the northern cities and towns. Visiting Greece with his close friend, Sir Geoffrey Jellicoe, he found inspiration in the way classical buildings and temples were placed on the landscape, how they related to each other. Jellicoe was highly influential in Sir Frederick’s personal and professional life. They visited a different town or city each year to gain appreciation and inspiration from the architecture, landscape and industrial designs of other countries. Their travels widened and developed Sir Frederick’s ideas of town design and before conservation was fashionable, Sir Frederick re-designed historic centres of old towns in need of refurbishment. His achievements with High Street and the village of Old Harlow represent his most important work in the field of conservation—an area chosen as one of the British examples for European Heritage Year, 1975.2 While Sir Frederick ran a successful private partnership throughout his career, his work for the Harlow New Town Development Corporation continued for nearly thirty years (Gibberd et al. 1980, 273). Sir Frederick inspired many up-and-coming architects, especially those who worked for his firm and those who read his architectural books.3 David Ives, a retired architect who worked for Sir Frederick in the late 1960s and early 1970s, reported that Sir Frederick was a fair employer who always treated his employees with respect. Ives indicated that Sir Frederick took the time to examine every detail of the work being done in his office (David Ives, personal communication).

3 From an architectural standpoint, Sir Frederick was heavily influenced by Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe and F. R. S. Yorke, the latter being noted for his work in the International Style (Fleming, Honour and Pevsner 1980, 137, 354; Yorke and Gibberd 1937). Sir Frederick’s work reflects modernist influences and it reveals his affinity for “critical regionalism.” In his work The Aesthetics of Landscape, Steven Bourassa describes critical regionalism as a phenomenon within a postmodern development that “recognizes the importance of context … and of local culture, climate…topography and other elements of the regional context” (1991, 23). Similarly, Kenneth Frampton, in his book Modern Architecture, discusses key elements characteristic of critical regionalism. In particular, he notes:[It] … is regional to the degree that it invariably stresses certain site-specific factors, ranging from the topography, considered as a three-dimensional matrix into which the structure is fitted, to the varying play of local light across the structure. (1992, 327)Likewise Sir Frederick’s work within Harlow New Town reflected how the natural landscape was to be incorporated into the creation of the town. His own thoughts and inspiration surrounding the landscape are relevant to an understanding of his work in Harlow. He wrote:Of all the landscapes worth preserving, to my mind it is the Valleys which are the most deserving. It is here that man’s intervention is at its greatest and the scene most diverse and intensified. The building groups were therefore placed on high ground between the valleys, which then formed an overall landscape pattern separating the building groups from each other. The landscape pattern is the complement of the building pattern. (Gibberd et al. 1980, 39)In his book Influential Gardeners: The Designers Who Shaped 20th-Century Garden Style, popular garden writer Andrew Wilson, further reiterated that Sir Frederick managed to encompass both qualities of modernism and critical regionalism into the design of his garden:…Marsh Lane, near Harlow, Essex, is the outstanding testament to his feeling for locality. This relatively modest composition captures a true sense of place, mainly through its scale and its success in combining hard and soft materials. Here, Gibberd experimented with concrete particularly, but also developed a sequence of spaces for the integration and display of sculpture. (2002, 166-67)One must note that not long after his work began on Harlow New Town, Sir Frederick moved his practice from London to Harlow. Later, he chose to work and live in Harlow. His home and garden on Marsh Lane is particularly captivating because of its integrative use of ornamental sculpture, a feature not altogether common in private modern gardens at the time. Yet, it is not surprising that within Harlow New Town, pieces of sculpture became incorporated within the city centre and surrounding neighbourhoods in the 1960s. According to Gillian Whiteley in her introduction to Sculpture in Harlow, Sir Frederick’s completion of Harlow New Town’s Water Gardens in the Civic Square in 1963 provided the impetus for the acquisition of new sculptures along with the relocation of many others (Whiteley 2005, 9).

The Gibberd Garden

4 Since garden designer (and wine connoisseur), Hugh Johnson recently credited the Gibberd Garden as being “one of the more outstanding gardens of twentieth century design,” it has received much acclaim in gardening publications, websites and gardening television programs such as the BBC’s Hidden Gardens program with Chris Beardshaw. In a recent feature of Essex Magazine, one journalist described it as an “Edenesque” garden (van de Laarschot 2001, 11), referring perhaps, to Sir Frederick’s incorporation of vistas characteristic of the “picturesque” movement (Symes 1993, 91-92).4 Though Sir Frederick was a well-known modern architect who incorporated landscape design into his town planning, the only private garden he ever designed was his own on Marsh Lane. Sifting through several architectural plans in Sir Frederick’s personal library and archives, I noted that he did produce garden designs for public institutions.5 While redesigning Coutts Bank in the Strand, he incorporated an indoor garden scheme within the interior foyer, a relatively innovative idea for a bank in the 1970s.

5 Sir Frederick’s Water Gardens was a large-scale public landscape designed as part of the Harlow New Town’s Civic Square. Sir Frederick produced an impressive water garden fully integrated with buildings, sculpture, extensive water features and seating and viewing areas. From the stone benches, pedestrians and shoppers could look across the Water Gardens where lay an impressive view of the Essex countryside. In recent years, however, the Civic Square was demolished to be replaced by a much larger building (the Civic Centre), which meant that the Water Gardens had to be shifted and completely remodelled. “The Water Gardens,” as it is now signposted in the high street of Harlow New Town, was an attempt to retain Sir Frederick’s design. Despite this claim, however, when pedestrians and shoppers sit for a quiet lunch and listen to the steady trickle from water fountains, the vista is no longer of the countryside, but rather of three big box-stores and a car park.6

6 When first asked to produce the initial master plan for Harlow New Town, Sir Frederick walked the footpaths and farm sites of Old Harlow and what is now the new town. That he strove to keep as much as possible of the original landscape surrounding Old Harlow intact while creating the new town is his strongest and most lasting impact. This aspect can still be seen, especially with regard to his incorporation of the “green wedges” of natural landscape separating the neighbourhoods of the new town (The Gibberd Garden Trust 2004, 26).

Sir Frederick Gibberd: Personal Context

7 Many people recall that Sir Frederick was a man of incredible style and flamboyance; he had the air of an Edwardian gentleman. Sir Frederick was remembered for his thick swath of grey hair, curly moustache and impeccable dress, usually a tweed suit complete with ascot, according to Gibberd Garden volunteer, Moira Jones (M. Jones, personal communication). He loved expensive cars and sometimes drove a Bentley. Sir Frederick and his first wife, Thea, had three children: Geoffrey, Katie and Sophie. Often, Sir Frederick would invite his entire staff to Marsh Lane for a party; sometimes on Guy Fawkes Night, which provided the occasion for a celebratory bonfire (D. Ives, personal communication). Thea died of cancer in 1970. Two years later, Sir Frederick married Patricia Fox-Edwards. As they were both founding members of the Harlow Art Trust, Sir Frederick and Pat had known each other for many years. Sir Frederick and Lady Gibberd maintained a London flat as well as the Marsh Lane residence for several years before moving to Old Harlow permanently.

8 During the mid-1970s, Sir Frederick began to expand the design of the garden. Lady Gibberd shared his interest in sculpture and fine art and she encouraged him to commission and purchase sculpture for the garden. They attended art shows and purchased artwork together. Pieces of sculpture would be left around the house or in the garden until the Gibberds’ became accustomed to them. The process of situating the sculpture could be labour intensive. Once a decision was made as to where to place a piece, Sir Frederick would call on his handyman-gardener, John Taylor, who assisted by pouring concrete, pruning hedges, sowing seeds, or doing carpentry work on the property. According to Lady Gibberd, Taylor could do anything, although he was not a “trained” gardener.

Creation of the Gibberd Garden Trust

9 Sir Frederick died in 1984, bequeathing his home and garden to the Harlow Town Council so that the people of Old Harlow and Harlow New Town would enjoy the property into the future. The Harlow Council, unfortunately, refused the bequest because of the terms of the will, which was later contested by his children. A series of court battles between his children and Lady Gibberd ensued. Meanwhile, a dedicated group of volunteers formed the Gibberd Garden Trust in 1995. This group then began the lengthy process of applying for a grant from the National Heritage Memorial Fund. Unsuccessful on their first attempt, assistance from the London-based Land Use Consultants (LUC) helped the group secure a £559,000 grant the second time (The Gibberd Garden Trust 2004, 30-31). With the funds they bought the house, garden and sculptures and conducted restoration work over a four-year period.7 Restoration gardener, Jean Farley, carried out the work with the assistance of part time gardener, Brian Taylor. Richard Ayres, MBE, retired Head Gardener of the National Trust gardens at Anglesey Abbey provided advice to Farley, Taylor and the volunteers involved in the project.8

10 Since most of the grant has largely been spent, the Gibberd Garden operates on a fairly strict budget. The entrance fees (£4), concessions, proceeds from the gift shop and tea room and donations are the primary income. Special events, such as jazz and classical concerts and childrens’ fun days bring in additional revenue. While the Gibberd Garden Trust owns the garden and the house, Lady Gibberd continues to live in the home.9 At one time, Lady Gibberd considered herself the garden’s chief weeder. With deteriorating health, she no longer weeds the garden, but she still serves as a member of the Garden Advisory Panel where her counsel is sought. As one of the few remaining founding members of the Harlow Art Trust, Lady Gibberd’s extensive knowledge of fine art, sculpture and craft is regarded as an asset. While the Gibberd Garden contains over eighty sculptures, Lady Gibberd continues to commission other sculptures for the garden in consultation with the Trust Committee.

Fieldwork, Observation, and Methodology of a Public Garden

11 As a folklorist and garden writer visiting this garden, I took field notes to document how people interacted within the garden spaces. In addition, I was fortunate to meet with and informally interview Lady Gibberd on three or more occasions. Primarily because of her passion for fine art and sculpture, and because of her influence on her husband’s work, I considered Lady Gibberd’s input essential to this study; without her lead, the Gibberd Garden would not have the volume and variety of art work that it does. While the garden has outstanding design principles, it is the sculpture that sets it apart from other gardens of the same period. Garden writer Jane Brown argues that the Gibberd Garden and architect Peter Aldington’s garden (Turn End), are the two eminent examples of English Modernist gardens of the 20th century (1999, 230-33).

12 In his astute description of the Gibberd Garden, Sir Geoffrey Jellicoe, a renowned landscape designer and close friend of Sir Frederick, emphasized that Sir Frederick had “a unique sense of the relation between one object and another …” a characteristic that Jellicoe felt “underlay all his work” (2001, 226). With this in mind, the Gibberd Garden might be analyzed as a material object created and recreated by one person, and altered and restored by many. Discovering who and what influenced Sir Frederick with regard to the garden’s design is to this author, an important aspect of this study. Yet, as Lady Gibberd noted on more than one occasion and reiterated in a conversation on July 17 2005 “everything and everyone is an influence … there is no one influence.” In addition to this direct and honest opinion of one close to Sir Frederick, this essay has also benefited from the views of others, specifically from scholars Mark Bhatti (1999) and John Dixon Hunt, in his in-depth study of reception theory and gardens, The Afterlife of Gardens (2004).

13 Through the assistance of the Gibberd Garden volunteers, Anne Pegrum (archivist) and Moira Jones (librarian), I was given access to Sir Frederick’s library and personal papers. My research unearthed several of Sir Frederick’s garden plans, architectural plans, personal drawings and correspondence from which I gained a further understanding of his gardening influences and garden philosophies. David Devine of the Museum of Harlow also shared resources about Sir Frederick in the form of articles about “the House” and the garden. Some of the interpretation of the Gibberd Garden in this essay stems from an intuitive article that Sir Frederick wrote for The Garden (the Journal of the Royal Horticultural Society) in 1979. Entitled simply “The Design of a Garden,” Sir Frederick provides detailed explanations of how and why he created the garden that he did.

Gardens as Material Culture: Gardens as Meaning

14 Gardens are forever changing. While gardens are natural products, they are used, manipulated and altered by humans. Just as material objects like furniture, quilts, or outdoor sheds are used and changed, a garden is a material object to be studied and interpreted to provide insights into the mind of the maker. Created, recreated and eventually restored by other gardeners perhaps years after its initial creation, a garden is not only an object, but also a process. As process, gardens represent meaning. According to Bhatti, there are four ways in which gardens represent meaning: (1) the garden as idea, (2) the garden as action, (3) the garden as place and (4) the garden as experience. As an idea, “the garden has served as a way of thinking about nature … about culture and how each influences the other” (1999, 189). In gardens, there is always a balance between human control and nature. Returning again to the words of Sir Geoffrey Jellicoe, Sir Frederick’s work reflected “a unique sense of the relation between one object and another” (2001, 226). Connected to this reflection is Sir Frederick’s feeling that the house and garden should act as one. It is not surprising that the more formal areas of his garden were near the house—an area of control and organized space. Even today, the wild garden is located at the bottom of the property nearest Pincey Brook.10 Sir Frederick qualified such formal and informal spaces: “The various rooms of the garden are broadly related to the environment in which they occur. Adjacent to the house they are formal, further away they are less formal until in the valley bottom everything becomes completely natural” (1979, 135).

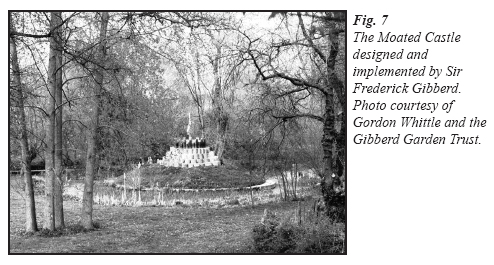

15 A garden can mean many things to many people. The explanations a gardener gives for why he gardens could be wide ranging yet interconnected. A garden may be defined by the actual activity of gardening. As a successful architect, Sir Frederick was driven by his career. Lady Gibberd recalled that he worked all the time. When asked if Sir Frederick’s garden was his hobby, Lady Gibberd looked at me incredulously and said “Hobby? It was more than that, it was his passion.” Similarly, Bhatti writes: “a considerable amount of effort and money is spent by gardeners on what is mistakenly called a ‘hobby’, but is actually an important part of the development of social identities and home making” (1999, 184). Importantly the creation of a garden is a very personal act steeped in emotions and social identities. It is also inherently about self. In many references to the garden, Sir Frederick notes that he made the moated castle and the tree house for his grandchildren. Lady Gibberd was emphatic that he made it for himself. In a conversation with me she reported “he was an extremely selfish man who created the garden to amuse himself.” While this might have been true, there is no doubt that children who visit the garden today find these particular features, among others, exciting spaces within which to interact. Sir Frederick’s child-oriented but man-made features—the moated castle, the tree house—along with specific child-friendly sculptures have not been lost on those who attempt to attract present-day garden visitors to the now very public Gibberd Garden.11

16 The word garden stems from the Hebrew word for “a pleasant place” (Bhatti 1999, 190). A garden can be understood from the perspective of a sense of place as well as a sense of space. The garden surrounding one’s home is a private space that can take on meaning in any shape or form, whether it is what some people refer to as a “grandee” garden or a suburban roof garden (Ken and Sheila Archer, personal communication). As indicated previously, Sir Frederick was extremely fascinated with the landscape around Old Harlow and indirectly the landscape that he shaped for Harlow New Town. When Sir Frederick initially saw the house and garden on Marsh Lane, he saw its potential as a garden space: “I bought the site … because it was an exceptionally promising one for making a garden” (1979, 131).

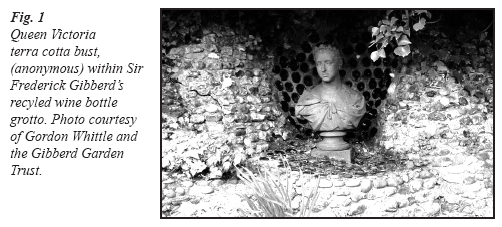

Fig. 1 Queen Victoria terra cotta bust, (anonymous) within Sir Frederick Gibberd’s recyled wine bottle grotto. Photo courtesy of Gordon Whittle and the Gibberd Garden Trust.

Display large image of Figure 1

17 As Bhatti indicates, the meaning of a garden can also be explained through the garden as experience. How one experiences a garden and how one experiences gardening can provide interpretative insight for studying gardens and garden design. Sir Frederick’s experience of designing this garden was akin to designing buildings; it was an art form, for he “consulted the genius of the place,” making the garden into a series of interconnected spaces that he, his family, friends and, eventually, the public could enjoy. On my first visit, I initially wandered aimlessly, without discomfort or frustration, feeling completely safe. I was enclosed in this space with endless opportunities to discover and rediscover Sir Frederick’s design within different garden rooms. In walking here, and turning there, I could see yet another direction in which to go. Stifling the urge to become completely distracted by all the twists and turns in this garden was half the enjoyment of being there. The following is an illuminating description of certain garden rooms that Sir Frederick wrote of in The Garden:Three sides of the lawn on the north of the house are enclosed by a screen of lime trees in which gaps reveal quite different scenes, each with a focus; the long narrow space of the lime walk terminates with a swan, the broad space of a paddock with dark trees and a stone torso and in a grotto a bust of Queen Victoria is glimpsed. Whichever of these three spaces you choose to enter there will be further spaces beyond and each one will have a different character. (1979, 135)On one of my many visits to the Garden, I spoke with a person who indicated that he had visited Sir Frederick’s garden at least five times. When I asked why he kept coming back, he said “the nice thing about this garden is that there is always something different … some new piece of sculpture.” While some people experience this garden from the perspective of how the gardener designed the borders and long vistas, still others enjoy discovering the sculpture found within the garden rooms.

18 Throughout his garden, Sir Frederick succeeded in incorporating plantings and sculpture—including pots, urns and found objects—as seamless elements within the garden spaces he created. Sir Frederick and Lady Gibberd’s choice of classic, modern and contemporary sculptures allows visitors to interact with the garden in a very human way. Visitors are not reprimanded for gently touching the sculptures, which many do. Gardening, in this sense, becomes a tactile experience for the visitor. Often, the works of art were bought from young, unknown sculptors who have since become recognized for their work—artists such as Fred Watson, Gerda Rubinstein and Elizabeth Frink, to name a few. When the Civic Centre was being built and the Water Gardens relocated, the town’s sculptures were placed for safekeeping in the Gibberd Garden until reconstruction was finished. According to volunteers of the Gibberd Garden, some sculptures worked so well within the garden that returning visitors were sorry to see them relocated to the town’s newly refurbished Civic Centre.

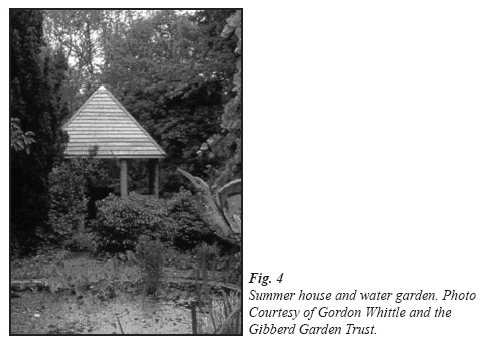

Garden Design Influences

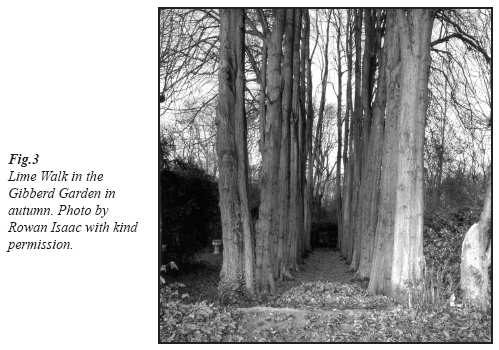

19 Judging by the substantial number of eminent and contemporary garden writers and garden designers whose works can be seen on Sir Frederick’s library shelves, one can ascertain to some degree who may have influenced him. First and foremost, Sir Frederick worked with Dame Sylvia Crowe, one of the first women landscape architects who popularized the field in Britain (Brown 1999, 225). She was hired by Harlow New Town Development Corporation to assist Sir Frederick with the landscape surrounding the different areas of the new town. A signed edition of her oft-quoted book, Garden Design (1958) is found in Sir Frederick’s library. While Sir Geoffrey Jellicoe was highly influential to Sir Frederick, it is evident that they inspired each other. Sir Frederick’s passion for British fine art influenced how he saw landscape. At one point, he explained to Jellicoe that his own collection of modern paintings “caused electricity to flow into him, leaving [this] fellow designer fascinated by the power of contemporary art …” (Jellicoe in Wilson 2001, 186). Sir Frederick’s library contains several of Jellicoe’s books, often filled with letters of encouragement from Jellicoe.

20 It is also possible that poet, writer and garden designer, Vita Sackville-West, may have influenced Sir Frederick’s garden design, chiefly through her use of “garden rooms”—an idea she made fashionable in the 1950s and 1960s. Her white garden—a separate garden room—within the gardens at Sissinghurst Castle in Sevenoaks, Kent, is world-famous. It is notable that Sir Frederick’s collection of garden books includes Sackville-West’s eminently popular series In Your Garden and In Your Garden Again (ca. 1960s). While Lady Gibberd did not recall Sir Frederick visiting any gardens that gave him inspiration, it is not a stretch to think that Sir Frederick’s series of garden rooms—which he referred to as garden spaces or compartments (1979)—were modelled after Sackville-West’s concept. Contemporary garden writer Andrew Wilson suggests that Sir Frederick’s garden “is of a deconstructed Sissinghurst, far more mysterious and savage than Vita Sackville-West’s creation. He used planting appropriate to the location and expressed the genius of the place in a subtle and reflective way” (2001, 186).

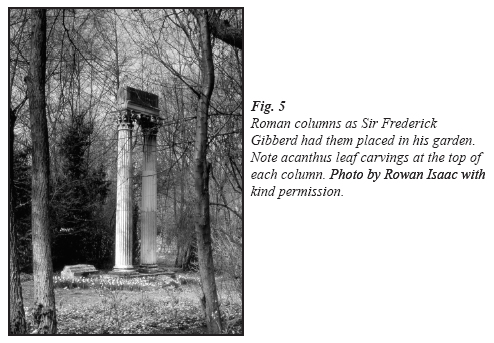

Garden Design, Garden Spaces: Sir Frederick’s Garden Legacy

21 Sir Frederick was an ambitious and highly successful modern architect. He was fascinated by British watercolours and by modern painting. His interest in sculpture included both classical and modern sculpture. Despite his architectural successes, Sir Frederick’s most important legacy is the ability he had to incorporate natural landscapes and man-made landscapes into well designed spaces. On the evening Sir Frederick was presented with the Royal Town Planning Institute’s gold medal, past president John Boynton stated that Sir Frederick’s legacy would not be the books he wrote or the master plans he had devised, but rather, the “three-dimensional” environments he created (1984, 30). It is clear that Sir Frederick was inspired and influenced by the world of art, architecture and landscape architecture. It is not surprising that he regarded garden design as an art of space:[For] the space to be a recognizable design{it} must be contained and the plants or walls then become part of adjacent spaces. As with architecture a series of rooms is made each with its own character: they can vary from small intricate spaces to those that embrace a distant prospect….There are no doors in a garden, one space extends into another, there is a visual reaction between them. The possibilities in design are endless. (Gibberd 1979, 135)

Reception Theory

22 Reception Theory recognizes that the audience, or the viewer, plays an important role in what may be called the realization of a “text” or what brings a text to life (Berger 1995, 23). Stemming from his work, The Afterlife of Gardens, garden historian John Dixon Hunt reflects on the kinds of garden constructions, features and elements that draw visitors to experience landscapes. Acknowledging it to be an approach applied primarily to written texts, he proposes the concept of reception theory as a means whereby one might analyze the garden. Hunt writes:The interaction between a literary text and the reader’s processing of it takes place in certain conditions that control that interaction; these have to do with genre, tone, structure, etc., as well as the social conditions in which it is read. The same is true of a garden, except that conventions and circumstances are different, even unique to that art; it uses different materials, involves the spatial experience of perambulation and (prime among the senses) viewing, and draws on assumptions that visitors bring with them about garden art and its different ‘genres’, such as public square, cemetery, sculpture garden and so on. (2004, 16)It would seem that as visitors to the Gibberd Garden, we are products of reception theory. Firstly, we bring to the garden our personal experience of “garden” and secondly, as we read and hear about this particular garden certain expectations develop regarding what will or will not be seen in it.

23 Before I visited this garden, I had a preconceived idea as to what I would see there.12 In the past, written reports, photographs or paintings of gardens provided potential visitors a glimpse of what would be encountered when visiting a particular garden, thus influencing how that garden might be interpreted. In the present day, photography and virtual web sites are continuously influencing how people visit gardens by providing details about what visitors will and should see: the style of the garden, the plantings used, the landscape vistas and, in some cases, the garden ornamentation. Hunt advises that garden visitors are often influenced on how they proceed into and through garden spaces; in effect, how the “beholder” (owners, visitors) appreciates and experiences the physical and sensual movement within a specific garden (2004, 116). He indicates that this movement is based on the way a garden path slopes, if it is covered in turf or gravel, the path’s width and the steepness and grade of the path, all of which have an impact on how quickly or how leisurely one goes through a garden (2004, 118, 148).

24 When Sir Frederick was alive, his garden was strictly private, although he did open it for charity events and company parties. According to volunteer Moira Jones, on these occasions, he thoroughly enjoyed showing the garden to guests. It is interesting, then, that Sir Frederick is often remembered for stating that his garden was to be explored and discovered, as opposed to being led through. It was his explicit desire, however, to make the garden public as indicated by his comments before his death and through the details of his will. Once this garden became public and received attention and admiration through various media—television, web sites, scholarly and popular publications and grants—the garden was no longer to be “discovered” for it already had been; now it is to be experienced according to what others bring to it and how they want to experience it. With this in mind, it is ironic that one of Sir Frederick’s most innovative design features was the series of triggers and prompts to visitors as they encountered different areas of the garden—the moated castle, the sculptures and the pond and waterfall, for instance. These features of the design as a whole are even more apparent as hundreds of visitors take the opportunity to visit the garden and, in some cases, write about it.

25 As the Gibberd Garden has become more financially independent, the Gibberd Garden Trust and its committees continue to make it more accessible. Through the work of a dedicated group, an illustrated brochure and map is now available to garden visitors. This brochure/map provides a listing, a brief description and a location key to every sculpture in the garden (the number of sculptures varies, but usually there are upwards of fifty or more in the garden).13 A detailed history of the garden and Sir Frederick is also available in a small colourful booklet, entitled Sir Frederick Gibberd and his Garden. Lady Gibberd indicated that the brochure/map, though a wonderful guide to the garden and the sculpture, gives visitors too much direction. She believes visitors are so busy checking the piece of paper in their hands and the sculpture in front of them that they tend not to see the garden and sculpture as one. The Gibberd Garden Trust Committee considered placing labels on each sculpture with a number to match the listed sculpture in the brochure, but there was a feeling among members that this would detract from the beauty of both the sculptures and the garden. It is significant that both publications—the brochure/ map and the booklet—contribute to the Gibberd Garden from a financial standpoint, but they also influence how this garden is perceived and received among visitors and would-be visitors.

26 Another significant way in which the garden has been considered is through the opinions of garden historians who suggest that Sir Frederick did not have garden plans. Sir Geoffrey Jellicoe states quite implicitly that Sir Frederick’s garden “was not preplanned” but “grew over a period of twenty-two years prior to his death” (Jellicoe in Wilson 2001, 226). Conversely, The Gibbon Garden Trust (2004) reports a garden restoration specialist used Sir Frederick’s original plans in order to restore and/or refurbish existing plantings after his death. With permission and a good deal of patience, researchers can have access to Sir Frederick’s archives and library in which his well-worn gardening notebook, complete with several pages listing plants and/or hand-drawn borders, can be viewed.14 Indeed, there are a number of articles that Sir Frederick wrote describing how he planned the design of the garden.15

27 Sir Frederick’s short article in the April, 1979 issue of The Garden is possibly the most up-to-date article that he wrote about the garden before his death in 1984. What became obvious in this article was Sir Frederick’s subtle form of “garden-how-to.” Sir Frederick stressed the importance of giving a garden its “bones” or skeleton by planting trees, shrubs and hedges while incorporating existing trees. He was also a “dirt under the nails” gardener because he always started the work himself. His handy-man, John Taylor, worked with him primarily on “hard scaping” (concrete walls, pavings) as well as tending a vegetable garden on the property. Although Sir Frederick admitted he was “not a plants man,” he filled every nook and cranny of his garden with plants because he felt that “in nature, soil is never bare” (1979, 132). Yet, he designed the garden so it could be enjoyed even in the cooler seasons as plantings throughout emphasize leaf colour and texture, such as that provided by Euphorbia, Salvia, Bamboo, Hostas, Rheum, and Gunnera. Sir Frederick was quick to point out that it did not concern him that his garden had few flowers (1979, 131).

28 Ahead of his time, Sir Frederick was a keen recycler of everyday items, many of which he incorporated into his garden. One of his more ingenious uses of recycled materials can be seen in the concrete and flint wall of a grotto he created to house a terra cotta bust of Queen Victoria.The wall and rockery is planted with Kenilworth Ivy, Primula, variegated English Ivy and Boston Ivy. The grotto’s wall consists of Essex flint, sea shells and the bottom ends of wine bottles wedged into what was initially a soft concrete and rubble mix. Glinting in the sun, blue and green glass bottle ends highlight the bust of Queen Victoria, sitting in her convex grotto-like shrine. This is located in a walled alcove beneath the area of the summer house or gazebo.

29 Sir Frederick remodelled the property’s Edwardian bungalow (ca. 1905) to include concrete and marble floors, a fifty-foot ceiling and textured wall surfaces. According to a 1963 article in House and Garden magazine, Sir Frederick redesigned the interior spaces so that he and his family could enjoy the garden from inside (35-38). Conversely, he altered and adjusted the exterior of the house to make it visually pleasing from the outside, replacing the gables with a pitched roof at either end. Inevitably, a large window on the east wall of the living room became the ideal place from which to view an impressive vista of the garden. As he indicated in the 1963 article, house and garden are essentially inseparable: “the design of the garden and the design of the window through which the garden could be seen, were regarded as one indivisible problem” (36). If one looks from inside the living room on the north side, one can look through into a walled and paved garden room where a Gerda Rubenstein sculpture depicting Sir Frederick’s head sits on a concrete plinth. Past this sculpture, the eye is drawn to an opening in the walled garden into yet another garden space (the main entryway) where a bony Madonna figure cradles a small child on her hip. A draping wisteria, an English privet hedge and standard yew shrubs provide the backdrop to the hardscape of paving stones and concrete blocks that define the walled compartments.

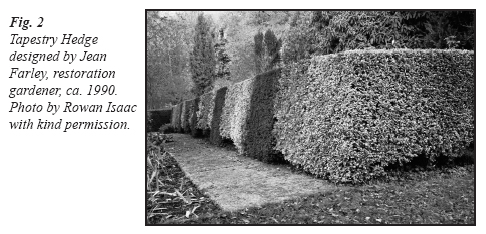

30 Sir Frederick often worked with one eye to the garden and the other to the house. The house is on an east-to-west axis with the land sloping down to the garden, the river and the woods to the north, and rising to the approaching lane to the south. Sir Frederick’s use of terraced retaining walls, steps and ramps give added dimension to the garden. Some garden rooms or compartments achieve further visual separation by a wall created from shrubbery or hedges. In several garden rooms within the vicinity of the house, the burnished look of paving stones blends well with evergreen hedges of variegated leaves. A carry-over from his architectural background, Sir Frederick was a strong proponent of the use of concrete. With John Taylor’s help, Sir Frederick poured the concrete for the paving stones himself. Before they were completely set, he hosed them down so they had a rough, textured look. Sir Frederick also utilized natural materials such as flint which is distinctive to the Essex topography. As a result of the restoration since the late 1990s, several additions provide the garden with a wider seasonal appeal. This is particularly evident with the multifold leaf colourings of the “tapestry hedge’s” fall display. Restoration gardener, Jean Farley organized the design and planting of this hedge.

The Lime Walk and the Roman Temple

31 In the article he wrote for The Garden, Sir Frederick indicated that he created a garden on a “small farm” where “there were no problems of preserving an existing garden” (1979, 131). Two fine features did exist at Marsh Lane when he purchased the property: an impressive lime walk, or allee, and a summer house or gazebo. Sir Frederick’s youngest daughter, Sophie, made a six-pointed star china mosaic for the floor of the summer house, while he removed the aged thatch that adorned the roof and replaced it with wood. Though he allowed certain original features such as these to remain, Sir Frederick was not afraid of altering and improving areas of the garden, for he recognized that “designing a garden is like making a series of pictures but unlike paintings they are in a state of constant change…” (135).

32 The lime walk or allee slopes down the valley on the centre line from the house where it dominates distant views, some of which have been filled in by maturing trees. An allee is essentially a series of trees planted in a line; sometimes these allees pierce a dense woodland (Hunt 1964, 87). When looking out over the patio area from the front of Sir Frederick’s house, the visitor can just barely see the entrance to the allee. The way in which it can be “discovered” and the beauty one finds upon seeing the lime walk has allowed this feature to be one of the most popular within the Gibberd Garden. Currently within garden history circles, as well as among Harlow residents, this feature of Sir Frederick’s garden is referred to as the “green cathedral.”16 With respect to reception theory, the lime walk, above all else, is a feature of the Gibberd Garden that visitors will experience and appreciate in their own way, based on their personal understanding and experience of a garden. As indicated again and again, Sir Frederick wanted each and every part of his garden to be just one more discovery (Gibberd 1979, 135). Similarly, gardener Brian Taylor indicated that “you cannot stop at the head of the terrace and look down and see the whole garden … you’ve got to be drawn into it” (B. Taylor, personal communication).

Fig. 2 Tapestry Hedge designed by Jean Farley, restoration gardener, ca. 1990. Photo by Rowan Isaac with kind permission.

Display large image of Figure 2

33 From the house looking toward the pool and water garden area, Sir Frederick added a series of concrete steps and ramps. Several large urns and clay pots filled with trailing ivy geraniums, scented geraniums and annuals are grouped between tiered landings. What was once a swimming pool is now a water garden filled with aquatic plants such as irises, water hyacinths, water lilies, purple loosestrife, sedges and grasses. A distinctive bird sculpture defines the space in the water garden, but just beyond, the eye is led past the pool to the summerhouse and a view of trees, sky and the surrounding countryside. In the distance, faint sounds of a passing train are sufficiently muffled by water trickling from Pincey Brook and the swishing of branches from large oaks and copper beeches.

Fig.3 Lime Walk in the Gibberd Garden in autumn. Photo by Rowan Isaac with kind permission.

Display large image of Figure 3

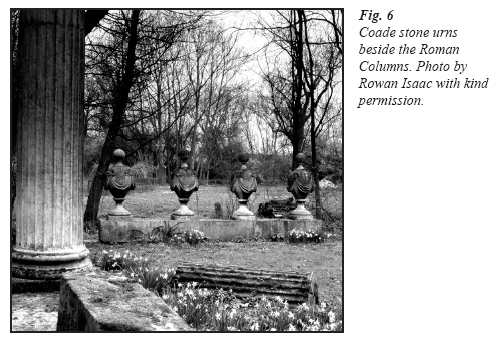

34 Not only did Sir Frederick buy sculpture for the garden, he rescued salvageable items from building sites. Such objects are found in several of his garden rooms. Just to the left of the lime walk, Sir Frederick placed two baptismal fonts; one font represents Romanesque architecture, the other represents decorated gothic architecture. These fonts serve both decorative and functional purposes for each is planted with trailing annuals. The most impressive of the salvaged items, however, are the decorative ruins of a Roman Temple, originally from Coutts Bank in the Strand, London. The building was being redesigned by Sir Frederick’s firm and he seized the opportunity to secure them for the garden. This relatively new addition to the garden was widely publicized in the local papers at the time of its placement. Harlow’s Gazette-Citizen provided an in-depth discussion of how Sir Frederick finally “got his folly.”Harlow’s master planner … is always full of surprises … and perhaps his biggest surprise yet is resting in a green glade in the architect’s rambling country garden on the edge of town … between the trees and bushes now rise two high pillars reminiscent of the glory of Rome. The noble columns flanked by four urns were saved from destruction by the demolition men and now form a “folly”…. It took a week to get the tons of masonry down to Harlow—and a whole day for the procession of three lorries and a crane to make their way down narrow Marsh Lane which leads to his home … it took another five days and three men to put them up … Sir Frederick: “I have made a special glade to take them which I shall plant with cypress trees…. There is a mound of earth in Temple Fields where Harlow had its Roman temple. You could say I have put it up again in my garden.” (1975, 231)As one passes through a series of poplar trees and the dark recesses of several evergreens, these columns loom out quite suddenly. While they are massive, Sir Frederick no doubt assumed that the trees would, in time, be taller and in better proportion to the columns. Still, even now the columns flow surprisingly well within the line of trees. Four urns of Coade stone are arranged to the left of the columns. It might also be presumed that Sir Frederick knew how well these columns would work in any season and in any weather. The columns appear more luminous and more like ruins when seen on a misty day than when the sun is shining. Today, the area just under the columns is densely planted with perennial acanthus which matches the acanthus leaves carved in the Portland stone capitals of the columns. The acanthus leaves are also used for the Gibberd Garden logo.

35 Beyond a comfortable grassy area—where visitors often sit and relax—a twisty stretch of recently planted willow trees is woven together to form a tunnel. Within this area, visitors can hear the babbling of the brook which lures one, unmistakeably, to the moated castle. Sir Frederick’s sense of sheer playfulness comes to full force in the creation of his moated castle, situated on a mound of earth formed by the spoils from digging the moat. The castle was once made of concentric circles of circular elm stumps. These have since rotted and have been replaced by concrete that was poured into cylindrical shapes. Adding to the aura of knightly spaces, a minute drawbridge can be raised or lowered.

Fig. 4 Summer house and water garden. Photo Courtesy of Gordon Whittle and the Gibberd Garden Trust.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 6

36 Other areas of the garden contain childlike sculptures and/or fixtures, such as a large tree house. Visible to the right of the tree house, a large wooden swing is suspended by long ropes from an outstretched branch of a massive oak. Swinging from the seat of this enormous swing (an action difficult for even an adult), the occupant looks towards the moat, all the while enjoying an impressive vista of trees. While many visitors and volunteers, not to mention popular garden writers, indicate that Sir Frederick designed the moated castle and tree house to entertain his grandchildren, there is little doubt that it amused and entertained him as well, as Lady Gibberd proclaimed. Sir Frederick did admit that the garden was the most self-centred of his creations. Gibberd Garden Trust librarian and secretary, Moira Jones reports that some people feel his garden was the most important of his undertakings. Sir Frederick spoke about the garden and garden design in an undated BBC television program, Omnibus:Once you look at the garden as a design then it becomes an art form and a very difficult one. You are concerned with first of all … with form, colour, and texture and it’s all complicated because it changes over the season and it changes over the years. And I think it’s probably the most complex art and the most difficult art that I’ve certainly ever worked at.17Sir Frederick was not afraid to change the landscape for he stated that, “respect for the character of the site does not just entail preservation” (1979, 134). Sir Frederick was very driven; if he got an idea he would not rest until it was acted upon, according to Lady Gibberd. He often moved great quantities of earth to form mounds and hills, or to create pools and other areas to site the sculpture. In one situation, he and his son-in-law spent an entire day digging a hole to situate a fountain and chrome steel sculpture. Sir Frederick indicated the successes and frustrations of using sculpture in the garden:Unlike most crafts which can be incidents in the garden scene, works of sculpture require a special setting involving such factors as appropriateness and scale. My wife and I collect sculpture and we find a site where both sculpture and the garden are enhanced. This sounds simple but is often very difficult…. Sometimes the right site does not exist and so I make a garden for it…. There have been garden compositions that seem to demand sculpture as their focus and if a suitable work cannot be found we commission one—a fascinating process for the sculptor’s eye sees differently from the garden designer’s…. Sculpture is more than skill in the making, it is the communication of feeling. (Gibberd 1979, 136)

The Gibberd Garden Today

37 It is essentially through the dedication of trustees, committee members and volunteers that the Gibberd Garden exists today. Before the Gibberd Garden Trust took ownership of the property, volunteers came on occasional Sundays to open the garden to the paying public and to serve tea. Serving tea was no simple matter as volunteers had to carry the water from town as the spring water on the property was not “fit to drink” I was told. Presently, the Gibberd Garden Trust and its committee have substantially taken over the administrative affairs of the garden and the gift and tea shops. A Garden Advisory Panel consists of volunteers who perform garden tasks two or three days a week, sometimes with gardener, Brian Taylor directing the work. Many volunteers come “in good will” to work in the garden, tea room or gift shop in order to make the garden a pleasant place to visit (J. Boyce, I. Collins, M. Jones and J. Whittle, personal communication).

Conclusion

38 Sir Frederick Gibberd created a garden utilizing existing features in an otherwise garden-free landscape. He saw the potential for realizing a series of house and garden spaces for himself and his family. In the 1970s, Sir Frederick established garden rooms so he could include and incorporate a collection of classical, modern and contemporary sculpture, along with salvaged or found objects. Shortly before his death in 1984, he had begun a design for a garden maze; this feature would have been in keeping with his childlike fascination for fun and functional garden spaces for the young and old alike (Lady Gibberd, personal communication). It reiterated that Sir Frederick was an avid planner of his garden and the garden’s future spaces.

39 Sir Frederick understood his garden as “place” and “art form” in which ideas, actions and experiences could be accomplished. Significantly, Sir Frederick’s garden on Marsh Lane—now the Gibberd Garden—is a testament to his sense of appreciation for the topography and climate of Old Harlow and Harlow New Town. His appreciation of the natural landscape is demonstrated with his use of the grand vistas of the Essex countryside—within his own garden spaces as well as landscape spaces surrounding the new town. Sir Frederick was influenced by a number of skilled and famous architects, garden designers and landscape architects. Still, what he created in his own garden was essentially a merging of many formal and informal garden styles vivaciously integrated with sculpture. Sir Frederick emphasized what the garden meant to him in many publications, especially in articles he wrote in 1963 and 1979. He emphasized his appreciation for gardens because he saw them as transitory, ever-changing art forms.

40 This essay has explored how gardens, through their designers and visitors, draw us in by virtue of descriptions through printed sources, maps, garden plans and virtual web sites (Hunt 2004). In this study I have approached the Gibberd Garden as an object of material culture. This garden has been altered and manipulated to include a variety of sculptures, found objects and man-made but child-like features. Sir Frederick’s garden exemplifies that a garden as object, art form and creative act can be interpreted and appreciated by designer and visitor alike.

Fig. 7 The Moated Castle designed and implemented by Sir Frederick Gibberd. Photo courtesy of Gordon Whittle and the Gibberd Garden Trust.

Display large image of Figure 7

41 Sir Frederick’s garden was never meant to be what one garden volunteer described as a “sleeping beauty garden” for this garden is continuously changing to accommodate the 21st-century world in which it currently exists (Inger Collin, personal communication). The Gibberd Garden Trust and its committees have dedicated time and effort in order that others may appreciate this garden’s subtle beauty and myriad vistas. Other gardeners have introduced new plantings, new structures and more sculptures all in the spirit of Sir Frederick’s original garden design. In keeping with these ideals, Sir Frederick Gibberd once said, “I don’t really think you can preserve a garden … it’s up to other people to develop it. I would hate to think that it would be frozen into this sort of design.”18

References

Anonymous. 1979. Coutts Bank Indoor Garden. Concrete Quarterly (September): 35-37.

———. 1963. Frederick Gibberd Makes a Garden in Five Brief Years. House and Garden Magazine (June): 35-38.

———. 1975. How Gibberd Finally Got His Folly. Harlow Gazette Citizen.

Berger, Arthur Asa. 1995. Cultural Criticism: A Primer of Key Concepts. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Inc.

Bhatti, Mark. 1999. The Meaning of Gardens in an Age of Risk. In Ideal Homes?: Social Change and Domestic Life, eds., Tony Chapman and Jenny Hockey, 181-94. London and New York: Routledge.

Bourassa, Stephen. 1991. The Aesthetics of Landscape. New York: Belhaven Press.

Boynton, John. 1984. Obituary – Sir Frederick Gibberd. The Planner 70(3): 30.

Brown, Jane. 1999. The English Garden Through the 20th Century. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Garden Art Press.

Crowe, Sylvia. 1958. Garden Design. New York: Hearthside Press Inc.

David, Penny. 2002. Hidden Gardens. London: Cassell Illustrated.

Devine, David. n.d. Sir Frederick Gibberd: A Brief Biography. Essay. Museum of Harlow.

Fleming, John, Hugh Honour and Nikolaus Pevsner. 1980. The Penguin Dictionary of Architecture. Middlesex, England: Penguin Books.

Frampton, Kenneth. 1992. Modern Architecture: A Critical History. London: Thames and Hudson.

Gibberd. Sir Frederick. 1948. Supplementary Architectural Report for the Oxford University Drama Commission. London: Geoffrey Cumberlege, Oxford University Press.

———. 1967. A Landscape Architect’s Garden. Gardener’s Chronicle 161 (22 March): 16-18.

———. 1967. Town Design. New York: Praeger Publications.

———. 1979. The Design of a Garden. The Garden 104 (April): 131-36.

Gibberd, Sir Frederick, Ben Hyde Harvey, Len White, et al. 1980. Harlow: The Story of a New Town. Benington, Steve-nage, Hertfordshire: Publications for Companies.

Gibberd Garden Trust. 2004. In Sir Frederick Gibberd and His Garden, 30-32. Harlow: R. M. Media.

Harling, Robert. 1967. The first Gibberd doodle … and how it became Liverpool Cathedral: “It came to be like a composer’s tune, readymade.” Sunday Times, 30 April.

Hunt, John Dixon. 2004. The Afterlife of Gardens. London: Reaktion Books.

Hunt, Peter, ed. 1964. The Shell Gardens Book. London: Phoenix House.

Jellicoe, Geoffrey & Susan, Patrick Goode and Michael Lancaster. 2001. The Oxford Companion to Gardens. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Perkin, George. 1979. A Sculpture Garden. Concrete Quarterly (September): 12-16.

Symes, Michael. 1993. A Glossary of Garden History. Shire Garden History Series No. 6. Haverfordwest, Dyfed: CIT Printing Services.

van de Laarschot, Lis. 2001. The Master Planner. The Essex Magazine, March.

Whiteley, Gillian. 2005. Introduction to Sculpture in Harlow, by The Harlow Art Trust. Harlow: The Harlow Art Trust.

Wilson, Andrew. 2002. Influential Gardeners: The Designers Who Shaped 20th-Century Garden Style. London: Octopus Publishing.

Yorke, F. R. S. and Frederick Gibberd. 1937. The Modern Flat. London: The Architectural Press.

Notes