Allotments As Cultural Artifacts

Heather KingMemorial University of Newfoundland

Résumé

En Angleterre, les pratiques relatives à l’usage des jardins familiaux ont évolué depuis le XVIIIe siècle. Leur contexte contemporain est à présent complexe, avec des éléments agricoles/horticoles. Historiquement, les jardins familiaux ont été attribués aux pauvres pour qu’ils puissent en retirer de la nourriture. De plus, légalement, les jardins familiaux conféraient aux pauvres le droit d’avoir accès à la terre. Cet article explore les jardins familiaux et ceux qui détiennent des lots de terres à Harlow, en Angleterre. Il examine à quel point les jardins familiaux et le jardinage sont enracinés dans la culture anglaise, et comment ils reflètent les identités et les valeurs de leurs locataires. En tant qu’artefacts culturels, les jardins familiaux signifient encore le droit d’avoir accès à la terre, mais ils ne sont plus exclusivement réservés aux pauvres. Toutes sortes de gens font aujourd’hui le choix personnel de devenir tenanciers d’un lot. Cette enquête démontre l’existence d’une multitude de sens et d’identités qui se reflètent et qui se déploient depuis l’engagement sensoriel avec la terre jusqu’au savoir traditionnel concernant le jardinage. En outre, cette enquête démontre la diversité de cette culture des jardins familiaux. La manière dont chacun des détenteurs de lots crée sa propre version du jardin familial s’entremêle à ses idéaux personnels, locaux et nationaux, démontrant innovation, créativité et ingéniosité. De manière générale, les jardins familiaux sont des sources de biodiversité et de pratiques bénéfiques à l’environnement. Sur le plan local, ce sont des espaces sociaux liés à la fierté, au bien-être et aux identités – ce qui est idéal pour la construction communautaire.Abstract

In England, allotment land-use practices have evolved from the 18th century. They now have a complex contemporary context with agricultural/ horticultural elements. Historically, allotments began as a provision to enable the poor to have food. Further, by law, allotments enabled the poor the right to have access to land. This paper is an exploration of allotments and allotment plot holders in Harlow, England. It examines how deeply-rooted allotments and gardening are in England’s culture and how it reflects the identities and values of tenants.As cultural artifacts, allotments are still about having the right for access to land, but allotments are no longer exclusively for the poor. People from all walks of life now make a personal choice to become plot holders. This inquiry demonstrates a multiplicity of meanings and identities reflected in, and ranging from, the sensory engagement with the land to traditional knowledge about gardening. Further, this inquiry shows the diversity of the allotment/gardening culture. How plot holders create their version of an allotment is enmeshed with personal, local and national ideals, demonstrating innovation, creativity and ingenuity. Globally, allotments are a wellspring for bio-diversity and environmentally friendly practices. Locally, these are social spaces linked to pride, well-being and identities—ideal for community building.1 Allotment land systems are valuable resources that are set aside for public use by Government Act. They are arable lands, usually within urban areas, that are leased to individuals for the cultivation of fruit, vegetables and/or garden plants. Each allotment is composed of a number of rectilinear plots and typically each plot is regulated by rental and allotment agreements. Allotment sites can be found in countries throughout North America, Australia, Europe (e.g., Germany, France and the Netherlands) and the United Kingdom (Cleves 1977, 19).

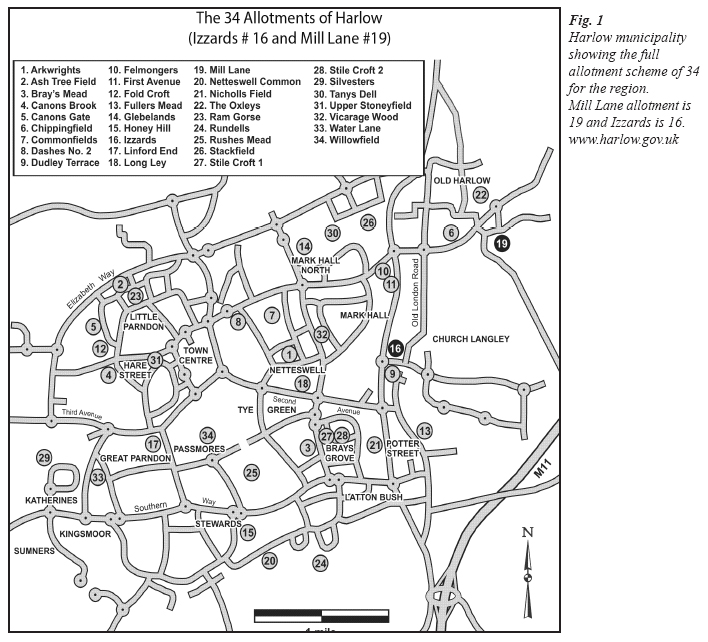

2 As cultural artifacts and from a material culture approach, allotments and plot holders reflect values of the culture. Material culture of people and objects involve multiple contexts and meanings (Glassie 1999, 53-61). In England, allotments as material culture have important connections to the past regarding land ownership and the English national identity. Allotments have existed in England since medieval times. Wealthy landowners initially provided them to tenants as a way to help the poor feed themselves. In 1969, the British government launched an inquiry into the loss of allotment lands to other purposes. The initiative (known as the Thorpe Report) resulted in a renewed commitment to the role of allotments in British life (Darren Fazackerley, personal communication). To this day, they continue to be a relevant part of the culture. Use of these plots is considered a leisure activity having complex meanings that are linked to England’s passion for gardening. The focus of this essay is on two allotments in Harlow, Essex, which are Mill Lane II and Izzards (Fig. 1).

3 Plot holders possess a wellspring of traditional skills, knowledge and oral history that define their identity and sense of place. While these important green spaces are in danger of being lost to urban encroachment, allotments are a natural reserve for knowledge that is relevant to contemporary issues like recycling, environmental responsibility, environmental preservation and biodiversity. Allotment work also enables users to become reconnected with the earth, and gives many of them a new appreciation for how food is grown. Other benefits include, physical exercise, stress relief, a sense of satisfaction, improved well-being, self-confidence and social interaction. This continues in the Harlow allotments of Essex.

British Allotments

4 Crouch and Ward (1988) write that several social and historical issues gave rise to the birth of the British allotment movement. These issues are deeply rooted in history and have affected the British attitude toward land and gardening. The authors suggest this directly impacts the underlying “...notion of entitlement to the accessibility of land...” which shapes how land is valued (20). They further believe it is important to look at this attitude as a process that evolved over time, starting with land enclosure (43).

5 Prior to the Industrial Revolution, the poor had access to common fields and common lands for subsistence: to erect a modest home, to graze animals, to collect firewood and to grow their own foods (45). The working relationship between the poor and the rich landowners was one of reciprocity or, at least, of mutual interdependence (Thompson 1991, 56, 95). With industrialization and urbanization from 1750 to 1850, the laws enacting the enclosure of common lands severely restricted access to resources that the poor needed in order to feed themselves and their families (Turner 1984, 16, 35, 83). According to E. P. Thompson, the attitudes of the poor toward the rich changed dramatically because enclosure exposed how the lower classes were the victims of exploitation and profiteering by upper-class capitalists (1991, 180). In 1806, an enclosure law was passed allowing provision for allotments for the poor, but it was not until 1845 that it became mandatory (Crouch and Ward 1988, 48). Discontent among hungry farmworkers ultimately lead to the Swing Riots of 1830 and 1845—periods marked by social and political unrest (Burchardt 2002, 231-36; Archer 1997, 23).

6 In 1843 a typical allotment size ranged from 140 metres square to 400 metres square (one-eighth to one-half acre), depending on the size of the plot holder’s family (Moselle 1995, 487). The first worker-allotments were started by Matthew Bolton and other industrial entrepreneurs, or philanthropists like Joseph Wright and Josiah Wedgewood, who instituted allotment programs as a means of increasing worker productivity and improving health (Harding and Taigel 1996, 238)—this was a strategy that sustained class disparity in the interest of capitalism. The other benefits of allotments to society were associated with the values of sobriety, thrift, self-help, self-respect, mutuality, reciprocity and industriousness. Providing allotments also helped to reduced criminality (Burchardt 2002, 235). In other words, behind the provision of allotments there was a conscious element of social engineering to control and maintain the status quo (Archer 1997, 25).

7 The next surge of interest in allotments in England came during World War I, and with the onset of World War II interest increased dramatically (Cleves 1977, 11). These wars transformed the attitudes of the British toward allotments. For example, during World War I, Buckingham Palace grew potatoes instead of flowers in their flower beds (Uglow 2005, 255). During World War II, allotments were no longer thought of as social programs only for the poor. The Dig for Victory wartime campaign meant that having and tending an allotment had crossed all lines of class, gender, age and level of skill in all areas of Britain (DeSilvey 2003, 454). Having an allotment became a patriotic activity and an expression of solidarity in the war effort; to have food, one had to grow it (Davies 1993, 30). During the war years food was not imported and Britain had to become self-sufficient in that regard. Every able person, including children, took part in growing food as a necessary part of survival. Britain also had to grow medicinal plants to replace drugs normally supplied by Germany. Thus, allotments and gardening became an even stronger part of British identity and a symbol of British culture.

8 Another development in British society that ran parallel to the development of the allotment was a passion for decorative/ornamental gardening and the landscape movement, which involved the upper and middle classes (Scott-James and Lancaster 2004, 52-61). These late-Victorian and Edwardian ideals and reformist ideologies formed part of Ebenezer Howard’s vision for the self-contained city, culminating in the Garden City Movement in 1898 (Aalen 1992, 48). This approach to town planning included green spaces for growing food and it established a link between protecting the environment and health. The movement raised the expectations of the working and lower classes for an improved, healthier standard of living. It also reinforced the existing conservative characteristic of Englishness; the valuation of the country Squire and the concept of the rural idyll came to represent perfection (Meacham 1999, 68, 182). Indeed, Meacham suggests that the people of Britain were told how to be English by the upper levels of society (7). The Garden City Movement was initially implemented to counter the out-migration of people from rural to urban areas. Allotments were part of the draw for factory towns, workers and town dwellers, which was reinforced by the cultural valuation of ruralness (Meacham 1999, 5). The elites and proponents of town planning defined a version of English identity and the virtues of Englishness, presenting it as part of the Garden City Movement with green spaces and allotments (Meacham 1999, 1-10). Allotments continue to be valued for their rural appeal and the ideals that rural represented.

9 Gardening, however, has been known in Britain since Roman times; formal gardening was introduced before the 1700s, and the Landscape Movement began in the 18th century. These developments and the land enclosures of that time were influential factors from which modern allotments evolved. With the start of exhibitions in the late 1800s, flowers and vegetables were both showcased, which resulted in the eventual coming together of both agriculture and horticulture elements (Scott-James 1981, 88-89). The convergence of both flower and vegetable components in a garden were also seen in older cottage gardens (Helmreich 2002, 68; Crouch 1992, 2; Scott-James 1981, 32-34). This is a more recent development in the contemporary use of allotments. The utilization and combination of both of these elements are also valued and reflected in allotments at Harlow.

Contextualizing Harlow Allotment Sites

10 In 2001, there were 80,000 members in the National Society of Allotment and Leisure Gardeners (NSALG) in the British Isles. There are 1,711 associations in total, each having more than 1,700 individual members, and there is a total of 146 local authorities (Harlow Department of Transportation 2002). According to Geoff Stokes, NSALG secretary, a national survey of allotment and leisure gardeners in 1993 by Peter Saunders, University of Sussex, mapped tenant trends (Geoff Stokes 2006, personal communication). Findings showed the largest cohort of tenants was aged fifty and older, at 65 per cent. The percentage of tenants with full time employment was 37 per cent, while 40 per cent were retired. Tenants’ occupations were predominantly professional/managerial/clerical (61 per cent), and 39 per cent were skilled and unskilled manual labourers. The national trend shows that younger gardeners tend to be from the executive/managerial category, whereas older gardeners are primarily manual labourers. Across all ages and occupations, the consensus regarding the motives for acquiring an allotment was personal fulfillment, enjoyment and satisfaction. The desire for fresh air, exercise and fresh food were ranked next in importance. In 1993, 16 per cent of plot holders were female and 84 per cent male—although Stokes estimated that the national rate of female tenants may now be at 20 per cent.

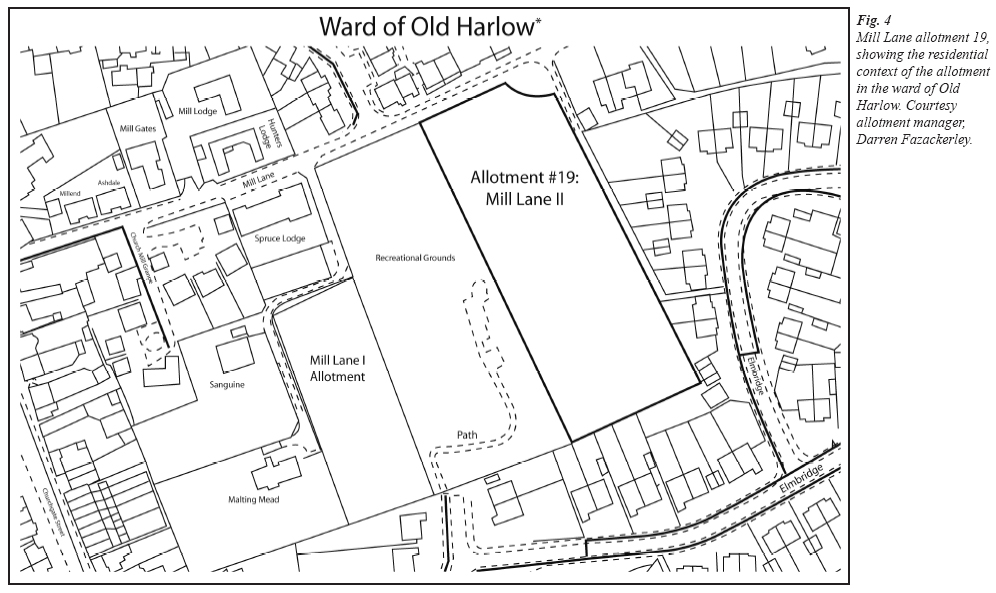

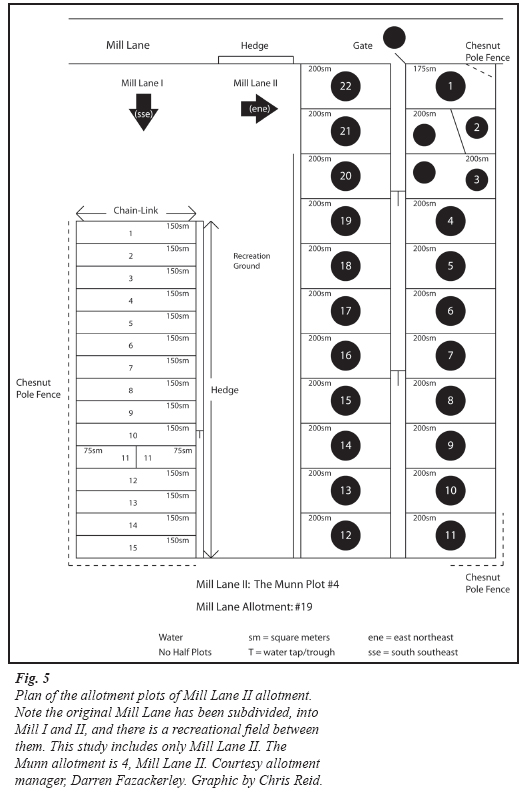

11 The population of Harlow Municipality in 2001 was calculated at 78,768 (www.profile.gov.uk). In this area, the largest ethnic group was white-British at 94.9 per cent, which means 5.1 per cent are British of other ethnic origins. The largest occupation group for Old Harlow is the professional, administrative, upper level and junior managerial at 44 per cent, and for Harlow Common the largest occupational class is skilled manual labour at 36 per cent. In contrast to the British national profile by NSALG, the Izzards allotment’s rate of Old Age Persons (OAP) tenants is lower at 26.6 per cent (the NSALG rate is 35 per cent). At Izzards, women comprise 15.5 per cent of plot holders, while men make up 77.7 per cent; the remaining 6.8 per cent of plots are co-held by male-female couples (Fazackerley 2006). Mill Lane II has 33.3 per cent OAP plot holders (that are not manual labourers); 9.5 per cent of the tenants are female and 90.5 per cent are male.1 Izzards thus has fewer OAP tenants than Mill Lane. Only Izzards has a small population of ethnic tenants. Mill Lane does not come close to the 1993 national rate of female plot holders, and if the rate is currently 20 per cent (as estimated) then neither allotment reflects the national average. The number of male plot holders at Mill Lane is higher (90.5 per cent) than the national rate of 84 per cent; however, at Izzards it is lower (77.7 per cent). This data supports the idea that Izzards shows more contemporary trends in allotment culture and Mill Lane II still maintains a more traditional form.

12 In Britain, the majority of allotment sites are governed by local councils (as they are in Europe). In addition, there is usually another regulatory body involved—the national association of plot holders. Britain’s NSALG began in 1901 as the Agricultural Organization Society. Today the NSALG sees its work with allotments and gardening as important for maintaining, protecting and preserving this significant part of British heritage and tradition (www. nsalg.org.uk). The organization provides benefits for gardeners such as insurance for allotments, supplies, a discounted seed scheme and a quarterly magazine. It assists in running shows or events and informs members about things like regulations and the restricted use of hazardous substances.

13 There are two types of allotments in Britain: those owned by private landowners, whose members are paying tenants, and those owned and regulated by the local municipal council, with members paying an annual rent to that council. Council allotments are either managed by the municipal council or self-managed by the members of each allotment. Council allotments are classed as either “statutory” or “temporary.” Statutory allotments cannot be sold or used for other purposes without engaging in a lengthy legal process. Temporary allotments are not protected by law and can be used for other purposes. Private allotments are classified as temporary allotments.

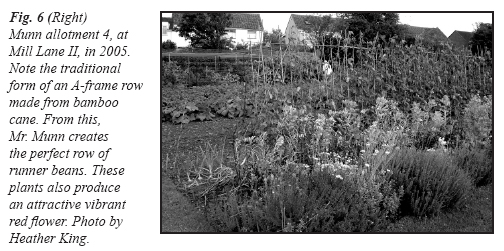

14 The greater Harlow area has thirty-four council-owned allotment sites, seventeen are run by council and the others are self-managed by the allotment holders (Fig. 1). The Izzards and Mill Lane allotments are located in the Harlow area. Harlow is, in a sense, both rural and urban, or town and country, and measures approximately 3,600 hectares. The larger New Harlow sector was designed by town planner and architect Sir Frederick Gibberd in 1947 and was built in response to postwar housing demands (Meacham 1999, 181; Biggins 2006). A key aspect of this designed town was that it had to have adequate green spaces. All of Harlow is indeed blessed with green space, despite the pressures of urban development.

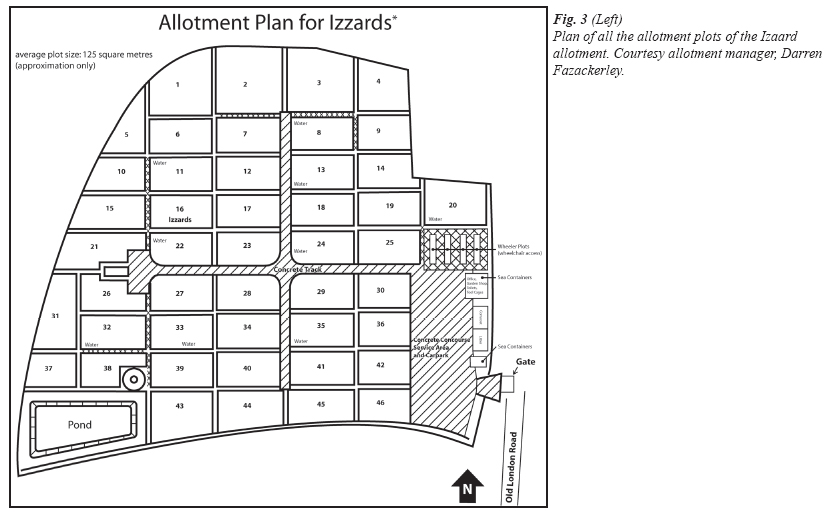

15 The Izzards allotment existed for a number of years but was moved to a new housing development site in Potter Street (Figs. 1-3). The creation of Izzards was the responsibility of the housing developer. The Thorpe Report stipulates that if six or more people request an allotment, the municipality must provide one (Garner 1984). Izzards was designed in 1996 by Darren Fazackerley—the allotment officer and landscape designer for the Harlow Council. This allotment has forty-five tenants and fifty-three plots.

16 A century ago, Colonel Gosling left the Mill Lane allotment site in the ward of Old Harlow in trust for the community; it is viewed as a covenant and is classed as a statutory allotment (Figs. 1, 4 and 5).2 As a covenant, the Mill Lane property cannot be used for development; it is statutory land and must always be used for allotments. In Gosling’s day this land was privately rented to tenants; today it continues to be cultivated, but as statutory allotments. The Mill Lane allotment has twenty-one tenants and twenty-six plots.

17 Unlike Britain’s older allotment plots, today’s plots are much smaller. Izzards, for example, is 125 square metres and Mill Lane II is 200 square metres. The older plots are sometimes subdivided into two. On the newer allotments, some tenants subdivided plots or added an extra one. To attain an allotment plot in Izzards or Mill Lane, an application must be submitted. There often is a waiting list, but when successful, the applicant signs a tenancy agreement. Tenancy agreements vary from allotment to allotment; a basic agreement may provide a water supply, for example. Other issues to be worked out relate to toilet facilities, site huts, sheds, adequate security, herbicides, pesticides, composting, sprinklers, bonfires and the responsibilities and duties of tenants (Harlow Department of Transportation 2002). Annual rents are determined by management, in accordance with the needs of the site. The levels of skill and the different gardening styles of the tenants ensure variation from plot to plot. Thus, the Harlow allotment sites are fertile spaces for the expression of gardening and culture.

Fig. 1 Harlow municipality showing the full allotment scheme of 34 for the region. Mill Lane allotment is 19 and Izzards is 16. www.harlow.gov.ukResearching Harlow Allotments

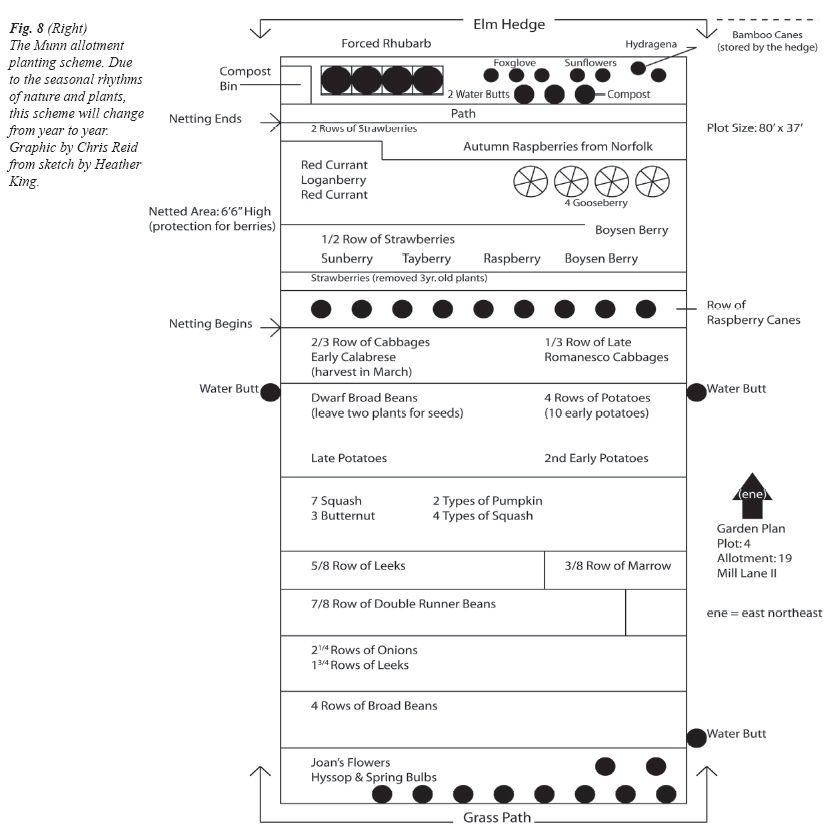

18 My research of allotments began six weeks before arriving in England. Prior to the six week field school that I attended in Harlow, I used the Harlow Council website to contact Darren Fazackerley, the allotment manager for Harlow. He arranged contacts with Joan and Edward (Ted) Munn, holders of plot four on allotment site nineteen, at Mill Lane II in Old Harlow. The site representative for Mill Lane II is Richard Parish; Dave Chalk is an assistant. Fazackerley also arranged a meeting for me with Derek Harris, secretary for the Harlow Allotment Association and the Horticultural Society. When I arrived in England, Fazackerley and I met with Harris at allotment site sixteen, Izzards, in the ward of Potter Street on July 3, 2005.3 During our informal tour of the area, Harris offered me tayberries and raspberries to sample, as well as three different varieties of carrots from his own plot. He spoke of Fazackerley as an ideal allotment manager, explaining that Fazackerley understands the needs of plot holders because he is a plot holder himself. Fazackerley was also very obliging; he provided me with maps and plans of both Mill Lane II and Izzards, and with important reading material regarding the allotments (Figs. 2, 3, 4 and 5).

19 On July 11, 2005, I met the Munns and spent the afternoon at their allotment. I took photographs of their plot, and we harvested some raspberries (Figs. 6 and 7). They then showed me other people’s plots on the allotment, after which we went to the Munn’s home for dinner. They were eager for me to know the sensory experience of tasting food from their plot. After dinner I did an audio interview with the Munns (as well as subsequent correspondence through email). I returned with them to their plot on August 1, 2005, when we measured the plot and recorded on graph paper how the plot was organized. I observed some changes in the garden since the last visit. I was then invited back to their house for tea. The highlight of the evening was when they proudly showed me the broad bean seeds they had just collected for next year’s crop, and some of last year’s runner bean seeds. In their living room, the carefully selected new broad bean seeds were spread on newspaper to dry.

Fig. 2 (Above) Izzards allotment 16 showing the residential context of the allotment in the Ward of Potter Street. Courtesy allotment manager, Darren Fazackerley.

Display large image of Figure 2

Allotment Nineteen Mill Lane II, Plot Four: The Munn Plot

20 The Munns—both seventy-five years old—are active retirees and avid gardeners. Mr. Munn refers to himself as a “Man of Kent,” meaning he grew up in an agricultural area in Kent, East of the River Medway. Mrs. Munn grew up in Kent, but during World War II lived with her grandparents in Devon, another agricultural area of England. In his earlier years Mr. Munn was in the British Army, after which he worked as a client site representative on major contracts, some of which were historic restoration projects. Regarding allotments, Mr. Munn worked as the site-representative for Mill Lane II, for a number of years.

21 The Munns live in Old Harlow in a two-storey, brick house that Mr. Munn built. They reared their family in the house, but both sons now live away from home with families of their own. Their property has a tiny front garden and a large one in back. The small, neat front garden is a public green space that showcases a few colourful flowers. In contrast, the back garden is a large, enclosed private space; it has a garage, a greenhouse and four compost bins. Most of the land is a cultivated vegetable garden. There is land between the house and the vegetable garden that is reserved for leisure and social activities. Mrs. Munn has an “L-shape” flowering border in the back garden that is her pride and joy; it separates the leisure area from the vegetable garden. The leisure area has a grassy lawn and a stone patio that are used for time with family and friends. They also have a few large fruit trees within the leisure area. The leisure space is directly accessed from the kitchen, and the transition between the two spaces flows easily. They have a concrete car park next to the stone patio and their back door. Having a home garden such as this in addition to an allotment suggests that the Munns highly value their gardens and are skilled, industrious and enthusiastic gardeners.

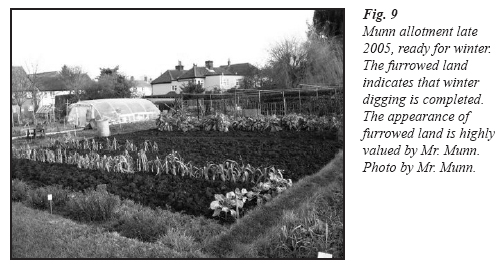

22 The Munn allotment is about one-and-a-quarter miles from their home; they have rented this allotment for more than twenty years (Figs. 1, 4 and 5). There were no allotments available when they first moved to Harlow from Kent. Mr. Munn initially was given access to the gardens of two private homes where he cultivated that land to grow his vegetables. In return, his obligation was to keep the grounds tidy. Mr. Munn refers to their allotment at Harlow as “Mill Lane II” because there is another section to this allotment that is just behind the recreational field next door (Fig. 5). He does not refer to the allotment as an “allotment garden” or a “garden.” Rather, he calls it an allotment or a plot. Carefully explaining the cultural difference, Mr. Munn clarified that an allotment is a plot one rents from the town, or ground one works in another’s back yard. A garden is the ground that is worked on one’s own property. A yard is used in reference to the older terrace houses; thus a yard that is covered in material has no land to cultivate. The perceptions of an allotment, a garden and a yard are culture-specific. These concepts relate to land ownership and how things are organized in this gardening culture.

23 Mr. Munn considers having an allotment and cultivating land to be a way of life. He and his wife have had an allotment since they were married in 1952 at Deal, Kent. As a child, Mr. Munn helped his father on their family allotment; although his grandfather did not have land, he had a greenhouse and especially liked to grow tomatoes. Mr. Munn’s ancestors were “aglabs,” or agricultural labourers/market gardeners, information he found in the British census. Mrs. Munn has worked on an allotment all of her life. Her maternal grandfather was a professional gardener, and she learned gardening techniques from him. She also helped her father on their allotment. For both of them gardening has been a lifetime pursuit, the skills of which were learned informally from their relatives, and more formerly from books like Reader’s Digest Guide to Gardening. Mrs. Munn has her granddad’s old gardening book, Outdoor Gardening: During Every Week of the Year (Keane 1869). It is used as a reference, but is cherished for its sentimental value. It is interesting that, in addition to being members of the NSALG, the Munns are also members of the Royal Horticultural Society of Britain (RHS). This information and their involvement in these agricultural/horticultural groups further reinforce the idea of gardening as part of their cultural identity.

Fig. 5 Plan of the allotment plots of Mill Lane II allotment. Note the original Mill Lane has been subdivided, into Mill I and II, and there is a recreational field between them. This study includes only Mill Lane II. The Munn allotment is 4, Mill Lane II. Courtesy allotment manager, Darren Fazackerley. Graphic by Chris Reid.

Display large image of Figure 5

24 Mr. and Mrs. Munn’s plot measures 24.62 metres in length by 11.38 metres wide. Standing on the path facing their plot, the garden points to an east-northeast orientation (Fig. 8). By the centre median, the first three rows of the garden contain Mrs. Munn’s flowers. She has spring bulbs in this area, as well as poppies and hyssop (Fig. 8). The hyssops are next to the four rows of broad beans. The next four rows are divided between leeks (one-and-three-quarters rows) and onion sets (twoand-one-quarter rows). Then there is a double row of runner beans followed by five-eighths of a row of leeks and three-eighths of a row of vegetable marrow. The rows continue with seven squash plants, three butternut, two types of pumpkin and four other kinds of squash. Then there are four rows of early, second early and late potato varieties. Part of one row has dwarf broad beans, but two plants of broad beans are left for seed collection. Next there are a couple rows of Calabrese and early Romanesco cabbages.4 From here on, there is an enclosure of fine netting that is two metres (six-feet-six inches) high, which covers and protects most of the fruiting plants (Figs. 6-8). The first row is filled with a number of raspberry canes tied to a wire trellis. The next row is empty, but it did have strawberries (after three years Mr. Munn discards strawberry plants). Then there is a row of sunberries, tayberries, raspberries and boysenberries. The following half-row contains more recent strawberry plants, which are cut back to aid regeneration; the rest of the row has boysenberries. From this point, there are two rows of fruiting shrubs that include a red currant, a loganberry and four gooseberry bushes. To the right of that are autumn fruiting raspberry canes from Norfolk. Finally, there are two rows of strawberries at the end of the netting. There is a small pathway that divides the next area from the netting section (Fig. 8). In this place, while facing east-northeast from left to right, there are a compost bin, four rhubarb plants, three foxglove plants, two water butts, a compost container, three large sunflowers and a hydrangea. Then there is a wheel barrow and a rusty bucket. Next to the hedge, there is another compost site, and this is an area where Mr. Munn stores his supply of bamboo canes. The hedge, which must be kept trimmed as a part of the allotment agreement, is also part of an elm fence border of the Mill Lane allotment.

Fig. 6 (Right) Munn allotment 4, at Mill Lane II, in 2005. Note the traditional form of an A-frame row made from bamboo cane. From this, Mr. Munn creates the perfect row of runner beans. These plants also produce an attractive vibrant red flower. Photo by Heather King.

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 8

25 The Munn allotment is an orderly system of rows, and management involves a number of environmentally friendly practices (Fig. 6). Mr. Munn remarks, “To say we are environmentalists, I would not go that far, but we try to do our best.” On this plot there are five water butts that hold about 180 litres of water each. This is part of the Munns’ system and efforts to conserve water.5 There is one butt at the front of the plot, one at the mid point on the right, one at the midpoint on the left and two at the back. Their plot has water service that they purchase and they use water keys to access it. They let the town water sit in the water butts long enough to allow the chlorine to dissipate, believing chlorine is not good for the plants. During water shortages, the vegetables usually are given more water than the flowers. The Munns employ a number of water conservation techniques. For example, Mr. Munn uses straw mulch to cover the ground to prevent moisture loss and to protect against weeds. When he plants squash and pumpkin, he places a bamboo marker by the crown of the plant. As the plant grows, because of the placement of the bamboo stick, he knows exactly where to pour the water for maximum absorption. Mr. Munn also noted that at home, when Mrs. Munn blanches the vegetables from the allotment and prepares them for freezer storage, she keeps the water and uses it to water the home garden. These actions demonstrate an awareness of the importance of water conservation.

26 Recycling is a major part of the allotment. All plant material from the garden is recycled, and while the Harlow council collects any materials that are too coarse to be composted by allotment owners, the Munns are keen composters. Mr. Munn uses a two-bin system for composting. Part of his process is to layer and stagger materials so that they decompose easily. He adds garotta powder which enriches and speeds the composting process; manure from animal farms is also incorporated. It takes six to nine months to complete a compost batch. Before using the compost, he removes the first nine inches of material. This is put in the base of an empty bin and it becomes the start of another batch. He does not put potatoes [stalks or haulms] in the compost “because of blight and it requires more heat to break down.” This was something he learned as a boy and is part of his traditional knowledge base. Besides using compost to enrich the soil, Mr. Munn uses “Grow More.” He explained that Grow More is a fertilizer that was developed during the war years to provide a good balance for the soil. Mr. Munn’s philosophy about soil integrity is that “You have to put goodness in to get goodness out,”—which refers to an interrelationship between humans and the earth. As well, he considers that all plants need nurturing, only weeds do not require care.

27 The Munns’ also have an alternative use for Mrs. Munn’s used nylon stockings. When harvested, pumpkins and other vegetables are stored in this stocking material and then hung in their garage at home. Mr. Munn also uses the same material to tie the berry bushes and to tie up the runner-beans as they grow. The stockings are cut into 2 cm (one inch) widths; he explained that the nylon fabric is soft and does not damage the vine or the fruit. These comments show that a high valuation is placed on their plants and fruits.

28 Allotments have been touted as ideal places for producing organic foods. According to Mr. Munn, it may be misleading to assume that what is grown on an allotment is necessarily organic. He does not see that as possible for allotments because neighbouring plot holders may not employ organic practices. He also believes that it takes many years for ground to become truly organic. The Munns limit their use of pesticide and then it is applied as a last resort. As well, there are certain substances that cannot be used because of government and European Union bans. They also practise companion planting as a form of natural pest control. Growing hyssop next to broad beans, for example, deters the black fly; onions next to carrots discourages the carrot fly, although the Munns no longer grow carrots. Another strategy used by allotment gardeners is to plant basil or French marigolds with tomatoes. Soapy water can be used as an alternate to pesticides, but Mr. Munn explained that a significant amount is required to destroy insects. Mrs. Munn remembers her granddad giving her a bottle of salt water and sending her, as a child, to pick caterpillars from plants. Saying it was all they had back then, her task was to drop the insects into the bottle. This technique of pest control was also practised during the Dig For Victory years in Britain and was often assigned to children (Davies 1993, 127-29). When pesticides are deemed essential, they spray only at night when birds are not around. They also use PBI as slug bait.6 Brussel sprouts require large amounts of pesticide to control grey aphids and for that reason the Munns no longer plant them. These various strategies are used to reduce as much as possible the impact of pesticides on the environment and, more particularly, they prefer no pesticides in their food for health reasons.

29 In Britain, there has been a long tradition of propagating one’s own garden seed, and Mrs. Munn has practised this technique for most of her life. Every year she propagates broad bean seeds that came from her grandfather Blake’s plants; they are called the Green Windsor Long Pod variety. Mr. Munn also propagates runner bean seeds from plants which originate from the seeds that Mrs. Munn’s father brought from the Dardanelles ca. 1918. These seeds are a part of their gardening heritage and are not available through retail outlets. When I first visited their allotment, they showed me some tattered looking broad bean plants. It was indicated that these plants were left to mature for seed collection, and although it may look messy it was viewed as a beautiful thing, something to be proud of. By the time of my last visit to the Munn allotment and home, two types of broad bean seeds had been harvested and were in the process of being dried. In a sense, because they propagate seeds from plants that they inherited and continue to preserve, they have been practicing biodiversity for years. This tradition is relevant for the contemporary issue of maintaining biodiversity. This unique practice ensures that certain plant strains have a chance to survive, in light of the recent trends to mass-produce only select strains of seeds.

30 Other techniques and tools employed for cultivation are still traditional in nature. His system of organization is to use simple planning strategies. At harvest time, for example, Mr. Munn puts bamboo canes on the four corners of the potato bed as a reminder not to plant potatoes in that area the next spring. In keeping with the concept of crop rotation, he puts potatoes in the same spot only every three years. He does not need a written record of his crop placements, but he has a mental map of his planting scheme.

31 Mr. Munn employs other methods of knowing from traditional wisdom, as well. For example, he said that the planting time for broad beans is November 12, which he refers to as “Twelfie.” He thinks Twelfie is a traditional reference that originates out of Norfolk. He also referred to Good Friday as the day that potatoes were traditionally planted. He suggested that was because it was the only day people were off work. Good Friday changes every year; therefore, he plants potatoes in the second- or third-week of April instead of on a specific date. He tries to cultivate his allotment in October or November, which he refers to as “winter digging.” He considers this to be the ideal time to cultivate (Fig. 9), calling it “ the poor man’s fertilizer.” He noted that, if you leave all the digging for the spring, the soil must be worked twice as hard to produce the same results. Winter digging is coarse digging. He leaves large clods and voids in the soil to allow the action of rain, snow, frost and oxygen to condition the soil and to replace the goodness absorbed by previous year’s plants. It is the work of the frost that breaks the soil down to a fine texture or tilth, which is ideal for planting. Compost or manure is added to the ground during the winter dig. As he explained, the nutrients are washed into the soil by the rains and are pulled in by the worms. For coarse winter digging, his custom was to use a “fens spade,” a type of spade used on the fens in the East Anglia region of England. He now uses a spring spade which was specially designed by a farmer for winter digging and given to him by Mrs. Munn. He prefers a fork for spring digging. Some of his tools are the same ones he has used for the past thirty years, and he still has some of his father’s gardening tools. He observed that “if you look at the spade and the hoe, they are all worn out on one side because that’s how you push it slightly more on one side, becomes smaller on one side.”

32 Mr. Munn spoke of the allotment as a place where people learn and copy techniques from each other. For example, there is a standard method to growing leeks, but Mr. Munn came up with a new way to cultivate them. His approach worked so well that some of the other plot holders have mimicked his new technique. Leeks typically have to be mounded, but Mr. Munn decided to plant his leeks in a depression. As the leeks grow he is able to mound them much higher than the traditional method, which results in a taller leek producing a higher yield.

33 Mr. Munn’s system for runner beans is to plant a double row which he meticulously measures (Figs. 6 and 8). He gets personal satisfaction from the aesthetic of a perfect row of beans—Munn said he is probably the only one on the plot who measures out spaces between the rows. (Mrs. Munn notes that “he measures to make sure his beans are parallel; he’s more tidy at the allotment than he is at home.”) He uses long strips of bamboo canes tied at the top and spread at the bottom in an “A” formation about 2.5 metres (eight feet) high. As the beans grow, they form a long narrow tent or a double row of beans. This traditional form can be seen at most allotments (Cleves 1977, 85-86). Mr. Munn also has his own technique for rhubarb. He has four rhubarb plants and each year he forces one of them in February. Focusing on a different rhubarb plant each year (allowing a three-year rest period for each plant), he puts a metal tube that forms a one-metre high collar around the plant. That plant will then send up long thin strips of rhubarb, which are more desirable.

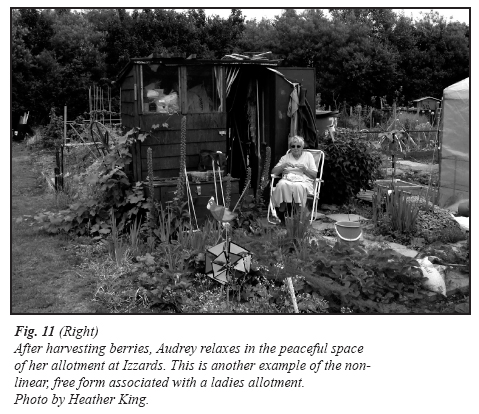

34 In reference to another gardening technique, Mr. Munn also mentioned a young man a few rows up from them has put in wooden boards to create a border around his plot. Munn said the young man was copying the technique from someone else. The prediction is that over the long term the border may not work. Despite this, Munn believes it is important to help, encourage and transmit gardening knowhow to the next generation of plot holders.

35 There are plenty of sheds on this allotment site; this is true for most other allotments that I have seen, but to avoid the risk of theft Mr. Munn does not have a shed on his plot—the boot of his car is his shed: everything he requires for the garden is in there, including a first aid kit should he need it. He brings a portable chair and sometimes he brings a thermos of coffee. In addition to sheds, some people also use locked chests on their allotment to store tools. In his reflection about men, sheds and working on the allotment, Mr. Munn also made the quintessential statement: “...they [men] are out of the way of the wife aren’t they?” He is a caring and loving husband, and Crouch (1989, 263) might sugest this may be more of a statement about removing oneself from the trappings or stress of everyday life. It is suggested that statements of this kind about escape can be indirect forms of resistance to institutionally-imposed controls and regulations, and about complex perceptions of freedom. While Munn has nothing against sheds, he sometimes considers those built out of scraps to be unsightly; he does not think they have to be done that way. He is an ex-serviceman and is retired from the construction industry; he values discipline and order, which is probably part of the reason he does not like an unsightly “ ram-shackled looking” makeshift shed.

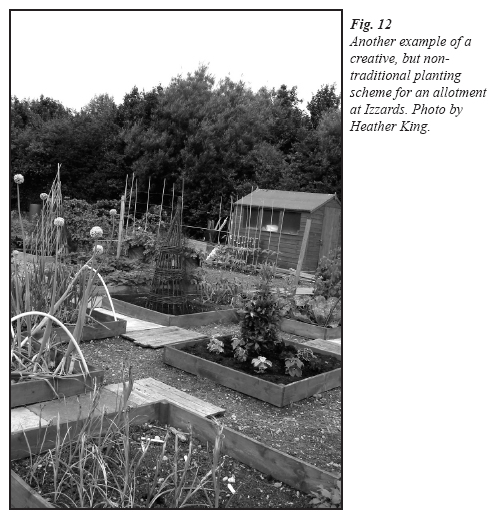

Fig. 9 Munn allotment late 2005, ready for winter. The furrowed land indicates that winter digging is completed. The appearance of furrowed land is highly valued by Mr. Munn. Photo by Mr. Munn.

Display large image of Figure 9

36 Allotment sheds can be a contentious issue it seems. The presence of sheds on allotments is either adored or abhorred. During our earlier mentioned tour of Izzards, Derek Harris advised that the tradition of creative reuse of materials on allotments is quite often reflected in the construction of allotment sheds. These sheds have a basic utilitarian purpose, but they also function as a private space within a public place in a rural/urban setting. Sheds are considered predominantly male domains, as reflected by the usual comment that sheds are places where men can escape. On a deeper level, this may be an expression of complex ideas of ownership, a form of resistance to dominance and regulation, each making personal statements of identity.

37 Another issue regards odours and allotments. Such smellscapes can have negative or positive associations (Porteous 1990, 21-45). The typical concern about the source of odours on allotments regards compost, manure and smoke, although in sensitive residential areas, regulations require compost to be enclosed, and manure materials must be covered to control odours and flies (Fazackerley 2006). In contrast, Munn stated the most offensive smell in this area is not from allotments, but from the larger nearby farms when sewer sludge is spread over the fields. The smell of smoke from fires is another issue, thus, the traditional practice of using fires on allotments for burning garden debris and for Guy Fawkes celebrations (November 5th) are no longer permitted. Smoke can irritate and be a nuisance, but Munn refers to these fires in a pleasant and nostalgic manner. At Mill Lane in 2005, Guy Fawkes night was nevertheless celebrated with a bonfire in combination with fireworks. Munn formerly did burn garden debris and considers it an effective way to eradicate plant diseases. He also noted the ideal conditions for a controlled burn of garden debris is at dusk, and that burning only dry materials minimizes the smoke.

38 With that said, allotments are also social spaces that are systems of sharing and reciprocity where British values and culture are expressed. This is a place where it is obvious that the notion of charity is a stereotype of Englishness. Munn mentioned that if you have extra plants you put them on the shelf or table in the poly tunnel for other members to take.7 If anyone has extra crops, they are laid on the rocks out by the front gate and any member is free to help themselves.8 As a group, another beneficial activity that saves money for the members is buying their potato seed and onion sets in bulk. Allotment members also help each other in other ways. For example, when Mr. Munn was in the hospital a few years ago, some of the men at the allotment ploughed the ground for Mrs. Munn so she could do the planting. Mr. Munn told me that “anyone who needs help we help them ... but we are not in each other’s pockets all the time you know.” If other members are away or on holidays, you may see a sign saying “Please Water Me” and sometimes they do that for each other. They often share tools. Reciprocity and charity are key elements of this social place.

39 There are some areas of tension that Mr. Munn mentioned, but for the most part he considers them minor issues. For example, what if the person next to you mows only half of the pathway between both plots, and you do the whole path? He also spoke of an experience of losing his water key. Others on the plot had not seen it. It was interesting that a few years later, when a fellow allotment holder died, they found six water keys in the man’s shed. Mr. Munn understands there are going to be arguments, misunderstandings and disagreements on any allotment, but he considers it insignificant, and his personal philosophy is that people are here to help each other, they cannot do without each other. He said they have become friends with other plot holders, and on the allotment people are friendly. Every summer they have a barbeque, and every Guy Fawkes night they have a bonfire celebration (despite regulations) to mark the end of another gardening cycle or season. Thus, the allotment is a social place, a place of friendship, that provides a sense of belonging.

40 At many points in the interview, Mr. Munn spoke of how satisfying it is for him to work on their allotment, even though he finds it harder to do now that he is older. As a case in point, he spoke of “...Christmas day, nine to ten vegetables on the plate and only one vegetable was not from their garden.” Such things give one a feeling of pride and satisfaction. He likes to see things neat and orderly, and reiterated that nothing is nicer than seeing a perfect row of runner beans (Fig. 6). The other thing he values and that gives him great pleasure is to see a freshly furrowed piece of land, whether it is their allotment or a large field out in the countryside (Fig. 9). He has no explanation for why he has these feelings, other than that sometimes soil smells sweet. This type of sensory engagement with the environment may express his feelings of connection to nature, his past and his identity. Some studies have expanded on ideas of human interaction with the landscape as more than simple sensory or emotive engagement (Porteous 1990, 1985, 1977; Davidson, Bondi and Smith 2005). It seems this intimate sensory engagement can be a passive expression of ownership by plot holders, but it is not ownership like that of formal institutions (Crouch 2003, 33). The Munns claim that unlike industrialized agriculture, the vegetables they grow have more flavour and the freshness is guaranteed. Mrs. Munn also pointed out that it is great to know what is in your food. These expressions of satisfaction, fulfillment and achievement contribute to quality of life and are ideal goals of healthy aging. Further, they are consistent with the research findings of Milligan, Gatrell and Bingley, which suggest that gardening can have a positive impact on the physical and mental well-being of older people (2004, 1791).

Izzards: Allotment Sixteen

41 The Izzards allotment is in the residential area of Potter Street; this allotment is another Harlow council site that is self-managed (Figs. 1-3). Derek Harris is actively involved with the management and operation of this site, which he does on a volunteer basis. He is a site manager for Izzards and his own plot is on this allotment. This is a modern site designed to meet contemporary needs. For example, in July the allotment was used by chef, Jamie Oliver, to film Big Cook Little Cook, a BBC television show for children. Thus, the allotment served as a teaching tool in ecological education. This project was designed to help people understand that food comes from gardens and not supermarkets.

42 When you enter the gates of this site there is a large concrete concourse (Fig. 3) used as a car park for plot owners. It is also a place used for service vehicles or for the delivery of goods and supplies by lorries. Most of the infrastructure for Izzards is in this concourse area. For buildings, they reuse and modify discarded sea shipping containers. In total, there are six sea containers on the site. Upon entry to Izzards, there is one sea container to the immediate left corner, and the other five are to the right; the first and last two containers on the right have built-in cages equipped with locks. Owners can rent these spaces to store their garden supplies and tools. These cages were supplied to safeguard against theft and vandalism, and as a substitute for sheds.

43 The second sea container houses the allotment office which has a desk, a computer, bookkeeping accounts and files. This space also has a long table and seven chairs, and is used for meetings and instructions. On the wall there is a companion planting chart; there are five silver trophies and a plaque on display. These awards are nostalgic or proud reminders of past competitions for the best allotment; these competitions that have since been discontinued.

44 Between the two (second and the third) sea-containers, there is a large three-compartment compost bin where allotment owners can drop their plant material to be composted; they also have a shredder on-site. All composted garden material will go back to the ground. The third container has an allotment shop where members buy their supplies. At the back of this unit there are washroom facilities. Harris noted that not every allotment has toilet facilities but increasingly there are more women who own plots, thus they needed a washroom facility. This refers to the idea that relieving oneself in an outdoor setting is less of a privacy issue for men than for women. Beyond the sea containers there are four raised garden beds with brick walls designed for wheeler (wheelchair) plot holders, or for tenants with minor back problems.

45 There are many sheds at Izzards; providing tool cages for members seems to have had little impact on the number of sheds. It is probably because the tool cages are expensive both to build and to rent. Sheds are technically discouraged, but the principle is not rigidly enforced. Fazackerley noted that the goal is to guard against the negative stereotype of having sheds on allotments that create the look of a shanty town. In theory, the sheds or greenhouses are supposed to be a standard size of 2 x 2.5 metres and 2.25 metres in height (six by eight feet and seven feet high), but sizes vary. Those who have sheds on their allotment are required to complete a registration form for the shed. The sheds can be made from any material, which leaves room for both building creativity and conformity. Sheds can be rented from Harlow Council, but there are no rented council sheds at Izzards or Mill Lane. Only two other Harlow allotments have these structures.

46 Harris indicated a plot where a man practises crop rotation by dividing his plot into six square segments (Fig. 3, plot 20). Each year he lets one of the squares lie fallow, switching to another section in subsequent years. This man’s traditional belief seems to be in accordance with Judeo-Christian biblical beliefs concerning crop rotation—the technique of letting land lie fallow every seven years is outlined in the Old Testament. The Munns practise a modified version of this with their potato crop. In a letter to this author dated June 13, 2006, Bryn Pugh, Legal Consultant for NSALG, advised that in Britain letting land lie fallow has not been done since the 14th century and on allotments it has never been practised. Plot-holders have ways to compensate for this by enriching their soils and using careful planting schemes.

47 It is only in recent years that ethnic British citizens began to exercise their right to allotments. On our tour, Harris pointed out two plots owned by ethnic British gentlemen. In one, a mature-looking man sat quietly in a chair surveying what appeared to be freshly cultivated ground. The owner of the other plot, which was partly harvested, grew only garlic and onions. On yet another plot, corrugated plastics are used to border and divide the plot. Harris noted that this plot holder is a contractor who builds and replaces conservatories; the materials he uses in his garden are discards from his construction contracts. The reuse of objects on allotments represents a “never waste anything” attitude that is part of this culture and generally accepted practice on allotments (Thompson 1999, 29).

48 Harris also showed me an example of what he refered to as a “Lady Plot.” The owner grows no vegetables, it is strictly ornamental with lots of flowers. The border of this plot is a low, neatly trimmed variegated hedge, grown from clippings collected from public gardens (Fig. 10). This plot is beautiful in texture, colour and form. This frugal plot holder also uses broken shards from clay pots in a walkway that winds its way through this micro landscape. Harris noted this lady lives in a flat and has no garden of her own. Thus, she recreates a home garden on her plot and enacts the right of access to land.

49 On another plot, Audrey was relaxing in a chair in front of her shed, having lunch (Fig. 11). Her allotment, contained a mix of flowers, herbs and food plants. Again, she did not organize her plants in rows or in a linear way; this is stereotypical behaviour for a Lady Plot. Audrey’s allotment was embellished and personalized with colourful whirligigs or wind jacks and miniature scarecrows. With her plot, Audrey seemed to create a home space for herself, a place to get away from it all, a place of leisure—a place of refuge where the lines between public and private, urban and rural, work and leisure become blurred. For Audrey, the personal choice of creating a beautiful landscape is valued over growing food.

Fig. 10 (Top) Example of a lady’s allotment plot at Izzards. A reflection of formal or ornamental gardening and a newer expression of culture on allotments. Photo by Heather King.

Display large image of Figure 10

Display large image of Figure 11

50 Harris has a wealth of knowledge about plants and takes great pride in that. He explained to me that a tayberry is a cross between a blackberry and a raspberry. He identified a horseradish plant, several types of artichokes and a Jerusalem artichoke. There were many spectacular showy flowers, like giant burgundy sunflowers and super-size dahlias, further demonstrating that allotments are no longer just about growing food, but places of pleasure and leisure with a hint of the exotic. He also explained how, on his plot, he staggers the planting of certain crops so that they mature in two-week segments. Harris showed me an example of an innovative way to grow potatoes, which was to grow them above ground in white plastic shopping bags that are approximately one half metre (one-and-one-half feet) deep. This results in higher potato yields, a more efficient way to conserve water, and a unique method of mounding the plant. He indicated that the plant is side-dressed by adding more soil to the top of the bag. To harvest the potatoes without disturbing the plant is as simple as rolling down the sides of the bag, removing some of the potatoes and pulling up the sides of the bag again. In a sense, innovations, the appearance of plots, tenants and allotment agreements reflect unique variations and diversity from allotment to allotment.

Conclusion

51 In contrast, the tenants’ agreements for Mill Lane and Izzards are different because of what they offer. Izzards is a newer facility; it has an on-site office, a supply store, secured tool lockers for members, a water supply and washrooms. Mill Lane has none of those elements other than water. Members at Mill Lane can purchase supplies at Izzards and have allotment meetings there. Izzards has raised brick beds for disabled members (Fig. 3); Mill Lane has a poly-tunnel type greenhouse for members to start plants, but it can be used by those who have minor health issues. In general, members at Mill Lane are in the fifty-plus age range, whereas, Izzards has more younger members than older ones. Izzards plots are half the size of those at Mill Lane, but Izzards is a larger site and has more members (Fig. 3 and 5). Mill Lane is more relaxed about sheds; Izzards provides lockers and the erection of sheds is strictly controlled (Figs. 3 and 5). The irony is that Mill Lane has fewer sheds than Izzards. There seems to be a concerted effort to discourage sheds and yet they are allowed. Izzards has a planning area which is used to give gardening instructions and demonstrations of how to care for an allotment. This planning area is a modern initiative designed to help those who have no gardening experience and to attract new members. Izzards also has a concrete service area and car park. The Mill Lane allotment looks traditional and the Izzards allotment looks contemporary with regard to how holders do their gardening (Fig. 12). Izzards also has more female designed plots than Mill Lane (Figs. 6, 7, 10 and 11). According to local plot owners, a “Lady Plot” is neither linear nor traditional in form, and is accentuated more by flowers and decorative elements than rows of food crops. The cultivators of allotments can be from all walks of life and they cross the lines of gender, age, class and culture. Plots are used for both agricultural and/or horticultural purposes.

52 Tenants on both allotments practise innovative reuse of materials and employ environmentally friendly practices like reducing use of pesticides, composting and water conservation. Allotments are micro communities where friendships often develop. Each allotment has an informal sharing system; plot holders help each other and sometimes care for each other’s plots during absentee periods. They also share gardening information and extra crops and plants are exchanged. Munn indicated that there is solidarity among gardeners in that he felt gardeners as a group are of one mind. Although today’s allotments are a far cry from their historic roots, they still function in the spirit of their origin. The council’s plots are provided at 50 per cent of the cost for the poor, for seniors and for people with disabilities.9 Gardening on allotments is still believed to be a healthy activity—but more importantly, allotments are artifacts that reflect the identities of their owners.

Fig. 12 Another example of a creative, but non-traditional planting scheme for an allotment at Izzards. Photo by Heather King.

Display large image of Figure 12

Gardening as Part of the National Identity

53 David Crouch suggests that allotments are cottage gardens without the cottage; thus, allotments and cottage gardens both share a common heritage (1992, 2; 1988, 187). He was not referring to the romanticized form of cottage gardens but to the everyday “plain” cottage garden. I asked Mr. Munn his views about gardening and the English national identity. He said the view of the English Country Garden that you see in magazines is the image that foreigners look for; something he noted would be difficult to find. He does agree, however, that gardening is a big part of the English national identity. The NSALG began as early as 1901, and the Royal Horticultural Society (RHS) began in 1804 and has a current membership of 371,000. These numbers and facts attest to the sustained interest for gardening in Britain. “The garden used to be the people’s pride and joy, but not so much anymore, yet, there are far more people who still take pride in their gardens than those who do not,” notes Mr. Munn. The Munns are RHS members.

54 Stephen Constantine (1981, 387-406) believes that evidence for the British preoccupation with, and passion for, leisure gardening is historical. That it continues to this day, is revealed through government statistics, and by the proliferation of the topic in popular culture (Yoe [1873] 2004; Moore 2005, 118-20; Thompson 1999; Opperman 2004; Low 1977; Genders 1975). This “nation of garden keepers” also has a keen interest in the study of English Garden History (Piras and Roetzel, 2005, 276). Darren Fazackerley also noted that holding an allotment has become trendy in recent years. Munn thinks that the land enclosure of the past has influenced how property is highly valued, and that most people in Britain value land because they are not landowners. He also mentions the pressures of modern living, the need for housing and car parks, the impact of increased motor vehicle ownership (a modern problem unforeseen by early city planners) and the shortage of land and space as issues that are part of the whole picture.

55 Enclosure of land may have been central to the creation of allotments in the past; at the same time, urban expansion threatens availability of allotments and arable lands today. Historically, allotments were social programs to help the poor have food; in a sense they are still social programs—only now for a healthier lifestyle cloaked in leisure activity. Allotments are self-help social programs that improve physical fitness and psychological health across a community; they are places of social interaction and community-building—fulfilling basic human needs. Further, allotments are places where traditional practices and knowledge are still viable, and can easily be perceived as useful for modern issues like recycling, organic food, a safe quality food supply, reducing food miles and a cleaner environment (Martin and Marsden 1999, 405).10 This has to do with the inherent connection of humans to land, and the current struggle to conserve land for future food production. As Mrs. Munn put it, “... years ago people did it to feed themselves out of necessity. Now people do it to feed themselves out of choice ... .”

56 Allotments are about multiple choices; DeSilvey found it difficult to define allotments in Scotland because of the diversity of allotments and the nature of what allotments are about, which includes historic and contemporary contexts (2003, 442-68). The findings of this research in Harlow correspond with DeSilvey’s. Crouch suggests that allotments defy conventional ideas and are unique blends of urban/rural, agriculture/horticultural, public/private, male/female, work/leisure, conservative/eccentric, exotic/mundane, historic/ contemporary, social/sensory and are multifaceted expressions of Englishness (Crouch 1988, 171-73). While working an allotment may be referred to as working leisure, Crouch noted that leisure/tourism industries do not view gardening as leisure (272). In an allotment, each individual has a private plot and yet an allotment is a small community of plots on public display to neighbouring plot holders. An allotment is a place where mundane vegetables like potatoes and runner beans are grown alongside formal ornamental plants, artichokes and exotic show-quality dahlias. This is a place where male and female allotment styles of gardening exist in contrast side-by-side. These are places of gardening diversity and individualities.

57 The Munn plot at Mill Lane II, with its emphasis on the value of orderliness and civic pride, reflects a conservative view of Englishness. At Izzards, Harris demonstrates the same principles, but also demonstrates liberalness and progression. Audrey’s plot (Fig. 11) shows a fusion of elements of leisure, work, a home away from home, freedom and a hint of creative eccentricity. Another woman’s plot at Izzards demonstrates a value for formal landscapes, a garden of pleasure and an opportunity to have access to land. As material culture, plots and allotments are clusters of representations and expressions of plot holders’ identities and their personal versions of culture as informed by history and contemporary issues. Even though the examples in this paper cannot reflect all concepts of allotment culture, it is possible that others can identify with many of the ideas. It is important to remember that allotments evolved from interpretations of rights to land and freedom of use of common lands, which evolved to, and was earmarked by, land enclosure. It is interesting that as cultural artifacts today, allotments have also become enclosed land set aside for public use. Allotments and their holders clearly show how land is valued and how it reflects who the users are. As a diverse gardening culture, it seems that no two allotments, plots or tenants are exactly alike.

References

Aalen, Frederick H. A. 1992. English Origins. In The Garden City: Past, Present and Future, ed. Stephen V. Ward. London: E and FN Spon.

Archer, John E. 1997. The Nineteenth-Century Allotment: Half an Acre and a Row. Economic History Review 50:21-36.

Biggins, Richard J. 2006. Pullman Court, Sir Frederick Gibberd. London: http://web.ontel.net/~rayuela/gibb.htm.

Burchardt, Jeremy. 2002. The Allotment Movement in England, 1793-1873. Woodbridge, U.K.: Boydell Press.

———. 1997. The Nineteenth-Century Allotment: Half an Acre and a Row. Economic History Review 50:21-36.

Clayden, Paul. 2002. The Law of Allotments. Crayford: Shaw and Sons.

Cleves, Bernard, ed. 1977. The Allotment Book: A Visual Guide to Successful Growing. Maidenhead: Sampson Low.

Constantine, Stephen. 1981. Amateur Gardening and Popular Recreation in the 19th Centuries. Journal of Social History 14(3): 387-406.

Crouch, David. 1989. The Allotment, Landscape and Locality: Ways of seeing Landscape and Culture. Area 21 (3): 261-67.

———. 1992. British Allotments: Landscapes of Ordinary People. Landscape 31(3): 1-7.

———. 1992. Popular Culture and What We make of the Rural, with a Case Study of Village Allotment. Journal of Rural Studies 8(July): 229-40.

———. 2003. The Art of Allotments: Culture and Cultivation. Nottingham: Five Leaves.

Crouch, David and Colin Ward. 1988. The Allotment: Its Landscape and Culture. London: Faber.

Davidson, Joyce, Liz Bondi and Mick Smith, eds. 2005. Emotional Geographies. Hampshire: Ashgate Publishing Limited.

Davies, Jennifer. 1993. The Wartime Kitchen and Garden: The Home Front 1939-45. London: BBC Books.

DeSilvey, Caitlin. 2003.Cultivating Histories in a Scottish Allotment Garden. Cultural Geographies 10 (October): 442-68.

Fazackerley, Darren. Living Harlow: Allotment Scheme. www.harlow.gov.uk/default.aspx?.

Garner, J. F. 1984. The Law of Allotments. London: Shaw and Sons Limited.

Genders, Roy. 1975. The Allotment Garden. London: St. Martins’s Press.

Glassie, Henry. 1999. Material Culture. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Harding, Jane and Anthea Taigel. 1996. An Air of Detachment: Town Gardens in the Eighteenth And Nineteenth Centuries. Garden History: The Journal of the Garden History Society 24(2): 237-54.

Harlow Council. 2004. A Guide to Harlow, 2004/05. Surrey: Burrows Communication.

Harlow Council. 2005. Allotment Gardening. Harlow: Parks and Leisure Services Department Information Services.

Harlow Department of Transportation. 2002. Allotments: a plot holders’ guide. London: DTLR, www.dltr.gov.uk.

Helmreich, Anne. 2002.The English Garden and National Identity: The Competing Styles of Gardening Design, 1870-1914. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Keane, William. 1869. Outdoor Gardening: During Every Week of the Year, 3rd ed. London: Journal of Horticultural and Cottage Gardeners Office.

Low, Sampson. 1977. The Allotment Book: A Visual Guide to Successful Growing. Maidenhead: Diagram Group.

Martin, Ruth and Terry Marsden. 1999. Food for Urban Spaces: The Development of Urban Food Production in England and Wales. International Planning Studies 4 (3): 389-412.

Meacham, Standish. 1999. Regaining Paradise: Englishness and the Early Garden City Movement. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Milligan, Christine, Anthony Gatrell and Amanda Bingley. 2004. Cultivating Health: Therapeutic Landscapes and Older People in Northern England. Social Science & Medicine 58:1781-93.

Moore, Jane. 2005. Allotments: What is an Allotment? Gardeners World, April.

Moselle, Boaz. 1995. Allotment, Enclosure, and Proletarianization in Early Nineteenth-Century Southern England. Economic History Review 68:482-500.

National Society of Allotment and Leisure Gardeners. 2006. www.nsalg.org.uk.

National Statistics Great Britain. 2005. www.statistics.gov.uk/census2001/profiles/22uj.asp.

———. Harlow. 2006. www.statistics.gov.uk/census2001/profiles.

Oliver, Jamie. 2005. Big Cook Little Cook. Chanel 4 Television Program, London, England: BBC Television.

Opperman, Chris. 2004. Allotment Folk. London: New Holland Publishers.

Piras, Claudia and Bernard Roetzel. 2005. British Traditon and Interior Design: Town and Country Living in the British Isles. Ed. Andrew Mikolajski. Trans. Harriet Horsfield, Karen Waloschek, Martin Pearce, Patricia Cooke and Phil Goddard. London: Konemann.

Porteous, J. Douglas. 1977. Environment & Behavior: Planning and Everyday Urban Life. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

———. Smellscapes. 1985. Progress in Human Geography 9 (3): 356-78.

———. 1990. Landscapes of the Mind: Worlds of Sense and Metaphor. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Scott-James, Anne. 1981. The Cottage Garden. London: Allen Lane.

Scott-James, Anne and Osbert Lancaster. 2004. The Pleasure Garden: An Illustrated History of British Gardening. London: Frances Lincoln.

Thompson, Elspeth. 1999. The Sunday Telegram: Urban Gardener. London: Orion Books.

Thompson, E. P. 1991. Customs in Common. London: Merlin Press.

Turner, Michael. 1984. Enclosures in Britain 1750-1830: Studies in Economic and Social History. London: MacMillian.

Uglow, Jenny. 2005. A Little History of British Gardening. London: Pimlico.

Uriely, Natan and Amos Ron. 2004. Allotment Holding as an Eco-Leisure Practice: The Case of the Sataf Village. Leisure Studies 23(2): 127-41.

Yoe, Alfred W, ed. 2004. The Cook’s A.B.C.: Teaching the Unskilled, at Least Cost, How to Cook Garden Food. London: Baskerville Press. (Orig. pub. Central Allotment Committee, 1873.)

Notes