Looking Backward and Moving Forward:

Early House Building Patterns among the Yorkshire Settlers of Chignecto

Peter EnnalsMount Allison University

Deryck W. Holdsworth

Pennsylvania State University

Résumé

On pense souvent que les immigrants en provenance d’une aire géographique bien circonscrite, et qui ont constitué des groupes ayant une bonne cohésion lors des premières colonies du Canada, auraient reproduit la plus grande partie de ce que l’on connaît de leur culture matérielle dans leur nouvel habitat. Il est raisonnable d’estimer qu’après avoir tout d’abord éprouvé leurs schémas culturels « traditionnels », les colons se soient adaptés aux nouvelles circonstances telles que le climat ou la disponibilité des matériaux, ou bien qu’ils aient abandonné les formes traditionnelles en même temps qu’ils apprenaient de nouvelles pratiques d’autres groupes culturels dans leur nouveau lieu de vie. Ces hypothèses générales fournissent le cadre d’analyse des pratiques d’habitation des colons de Chignecto, originaires du Yorkshire, en nous basant sur la documentation existante, les preuves à l’appui de la survie et ce que nous connaissons des schémas d’habitation précédant l’émigration. Cet article explore les formes d’habitat dans la région du Yorkshire d’où vinrent ces immigrants en tant que prélude à l’analyse de l’expérience de ces gens dans le nouveau monde.Abstract

Emigrants from a limited geographical area, who formed cohesive colonies in early Canada are often assumed to have reproduced much of their known material culture in the new setting. It is reasonable to expect that after the initial testing of these “traditional” cultural patterns, settlers might either adapt to new circumstances such as climate or availability of materials, or abandon the traditional forms altogether in the face of new practices learned from other cultural groups in the new setting. These general assumptions provide the framework for examining the housing practices of the Yorkshire settlers in Chignecto based on the available documentary and surviving evidence and what is known of pre-emigration housing patterns. As a prelude to examining the new world experience of these people, the paper surveys the forms of housing in the Yorkshire areas from which emigrants derived.1 The arrival of a colony of Yorkshire people in the Chignecto region1 of Atlantic Canada between 1772 and 1775 tempts us to look for some tangible imprint left by this group on the landscape. There is a natural expectation that this and other independently initiated emigrant groups would reproduce in a new region some aspects of their familiar material culture. Housing form has often been presumed to be one of the major forms of material culture that emigrants might reproduce faithfully because shelter was an essential requirement, and because it was one of the most traditional and enduring aspects of a group’s material life. Not surprisingly there is a substantial literature on the “ethnic house” in North America through which numerous scholars and observers have explored the degree to which groups have succeeded in reproducing and sustaining old world housing forms and building practices following their arrival on this continent (Cummings 1979; Ennals and Holdsworth 1998; Noble 1992; St. George 1988; Upton 1986). In this paper we explore the extent to which the Chignecto Yorkshire settlers imposed their housing traditions on the landscape of Atlantic Canada in the first generation or two following their arrival in the region.

2 If there is a weakness in the scholarship conducted in this vein in North America, it is that too often the antecedent housing practices are only faintly understood or, worse, are caricatured in the form of easily identifiable decorative elements, that may or may not be significant indicators of culture reproduction and authenticity. We caution that instead of viewing these antecedents as timeless and static, attention should be paid to the transformations that were under way in the decades prior to emigration. Furthermore, we would assert that while there may be some nostalgic elements in the more comfortable shelter that some immigrants were able to produce for themselves, for others the new houses they erected after a couple of decades were more often part of a progressive, forward-looking marking of their achievement in the new land. Our analysis begins in Yorkshire.

Antecedent Housing Form in the Yorkshire Source Area

3 The evidence suggests that some 98 per cent of emigrants who left Yorkshire for Chignecto between 1772-1775 were drawn from rural parishes and villages in the northern and eastern sections of Yorkshire, most notably from the upper Vale of York, the adjacent uplands of the Dales immediately to the southwest, the south-flowing valleys of the North Yorkshire Moors, and from the Tees Valley and coastal Cleveland.2 Few came from the Yorkshire Wolds or from the lowland arable zone stretching between the County’s principal cities of York and Leeds. Any effort to deduce the types of housing form that might have been familiar to these emigrants at the time of their leaving must be directed therefore to what we know of the evolution and typical patterns of this northern zone of the County. Fortunately there has been a great interest in vernacular housing form in Britain during the past quarter century and there is now a rich literature that permits us to reconstruct in broad strokes the primary forms of rural dwelling, their regional variations and their social class associations (Caffyn 1986; Giles 1986; Harrison and Hutton 1984; Royal Commission on Historical Monuments 1987).3

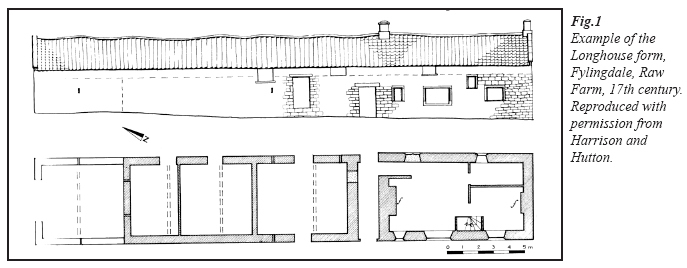

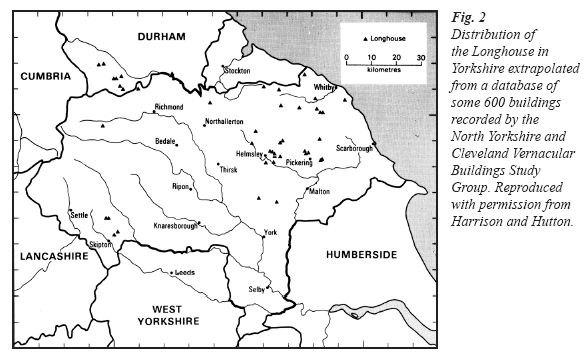

4 The longer history of post-medieval housing in the region produced two primary forms of dwelling type distinguishable by their scale, construction technique, materials and the interior plan. In broad terms these two forms also serve as useful indicators of the type of agriculture conducted by their instigators. The first type is the so-called “longhouse” form (Fig. 1), common in several parts of medieval Britain, particularly in pastoral and upland areas, such as the West Country counties of Devon and Cornwall, North Wales and including the North Yorkshire moors and the Tees Valley (Mercer 1975, Harrison and Hutton 1984). The form derives its name from the fact that the dwelling and byre (housing livestock) were joined producing an elongated one-storey form, with walls and roofing almost invariably constructed of stone and slate respectively. Though many of these buildings have now disappeared, British housing scholars using probate inventories from the 16th century in the Vale of York have identified this zone as one having significant numbers of the longhouse (Harrison and Hutton 1984). Indeed the Vale of York probate documents provide a remarkably rich source for assessing this housing type and its detail (Fig.2). It should be noted however, that the form was also evident in the area surrounding the city of York in the 16th and 17th centuries even though this was an area where arable land predominated (Harrison and Hutton 1984).

Fig.1 Example of the Longhouse form, Fylingdale, Raw Farm, 17th century. Reproduced with permission from Harrison and Hutton.

Display large

image of Figure 1

5 The evidence from these sources strongly suggests that the longhouse started to disappear toward the middle of the 17th century and disappeared entirely from some inventories by 1700. It has been argued that this reflected a change in the pattern of farming following the collapse of corn prices after 1650 (Harrison 1991). The ancient and craggy appearance of these dwellings and the fact that they were designed to allow their human occupants to share their housing with their animals might indicate that such housing was more traditional, more archaic and served a poorer farming class. This view has been challenged, however, by Barry Harrison and Barbara Hutton, who document many instances where prosperous farmers well-placed in the local social hierarchy resided in houses of this type (Harrison and Hutton 1984; Harrison 1991).

Fig. 2 Distribution of the Longhouse in Yorkshire extrapolated from a database of some 600 buildings recorded by the North Yorkshire and Cleveland Vernacular Buildings Study Group. Reproduced with permission from Harrison and Hutton.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 3

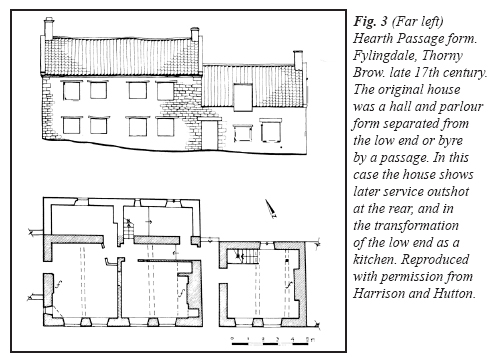

6 Efforts to map the distribution of this form provide a strong picture of the regional vectors of the type. As figure 2 shows, the longhouse survives most prominently in the upper end of the Vale of York and stretching toward the Tees and south-eastward toward the Humber. Overall, longhouses formed about a third of all houses in this area in the century after 1570, but it was rarely found in the richer more southerly parts of the Vale (Harrison 1991). Invariably built of stone and often roofed with slate, the longhouse consisted of a hall, which was the principal living space for the occupants and which contained the large hearth, the source of heat for cooking, and a parlour used for sleeping (Fig. 1). Access to the hall was by means of a passage adjacent to the hearth, hence the term “hearth passage” is one of the distinguishing forms of the longhouse typology. This passage served to separate the human dwelling from the “low end” where livestock were housed and other farm related functions conducted. Significantly the byre, or stable, occupied more space than the hall and parlour. It was perhaps also not surprising that the parlour and other services rooms might be placed beyond the hall to ensure further separation from the farm components of the building. The hall originally served a multiplicity of functions, including cooking and eating, all of which were accommodated without the need to further carve out special spatial enclosures.This pattern of a two- or three-celled hall and parlour plan represents a fundamental “folk” dwelling form and it occurs widely within the British Isles and the European continent before 1800.4

Fig. 4 Hearth Passage house at Helmsley with a full width parlour with fireplace. Note the unusually small low end in this example. The upper level represents a lifting of the original eaves to make a more usable upper level. Reproduced with permission from Harrison and Hutton.

Display large image of Figure 4

7 It is also the case that on the magnesium limestone belt and on the alluvial lands around the lower Ouse and Aire rivers, the characteristic “lower end” (byre) had become a kitchen for baking and brewing by the 17th century, suggesting that farmers there were beginning to find alternative quarters for livestock (Harrison 1991). The conversion of byre to kitchen led to the insertion of a second fireplace into this space such that the hearth passage separated two heated rooms. This pattern of change was evident progressively in other parts of the region as the 18th century unfolded (Fig. 5). Harrison and Hutton also indicate that many of these houses were further modified to create a second storey to provide additional sleeping quarters reached by ladders, or staircases added by means of an outshot on the rear of the dwelling (Figs. 3 and 4). In many houses this change permitted the ground floor parlour to relinquish its function as a bed chamber thereby becoming a true sitting room. These changes point to a shift toward a more functionally defined series of spaces within the dwelling and they reflect a general cultural movement that we have called the vernacular transition (Ennals and Holdsworth 1998).

Fig. 5 Map of the Hearth Passage form before 1750. This pattern was further concentrated around Helmsley by house building practices in the area after 1750. Reproduced with permission from Harrison and Hutton.

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 7

8 The other principal post-medieval housing form in the region was the timber-frame dwelling. As in the case of the longhouse, dwellings of this type found in Yorkshire resemble those found elsewhere in eastern England (Harrison and Hutton 1984; Harrison 1991). The common traits included the lobby entrance, close timber studding, the use of common rafter roof framing, the earliest of which employed crucks, which are split pairs of naturally arch-shaped tree trunks (Fig. 7). The most distinctive feature of these dwellings in the region is the aisle at the rear and sometimes at the ends as well, and the large firehood often located in a short “firebay.” A few of the surviving houses of this type reveal a hearth passage as in the longhouse, but most are distinguishable by their central lobby entry. These houses have been much modified (e.g., by being encased in brick and having the timber firehoods replaced). It is thought that some “half-bays” found in extant houses of this type may have been firebays, but they may also have been cross passages.

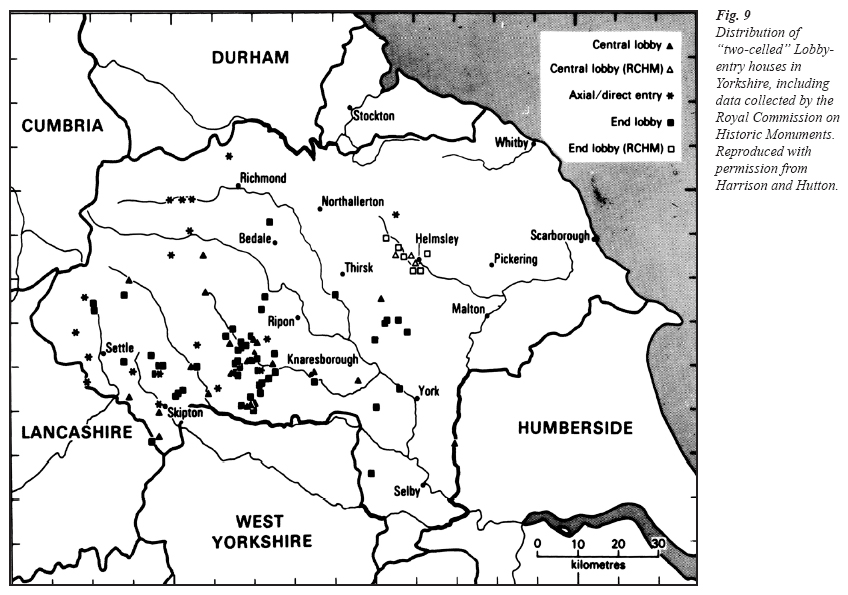

9 The typical pattern for houses of this type in Yorkshire was a plan consisting of two or three rooms in line with an internal chimney stack set as the dividing wall between two of these rooms (Figs. 6 and 8). The front door opened into a lobby in front of this stack. As in the case of the longhouse, the hall was the main room dominated by the hearth. The adjacent rooms might also have fireplaces making these dwellings comparatively more comfortable. Most had lofts above which served as chambers for sleeping. Commonly there were a series of service rooms along the back aisle and this sometimes resulted in an outshot—a room that projected beyond the line of the dwelling. Later rebuilding often resulted in a back-to-back fireplace thereby increasing the heating opportunities within the dwelling. Houses of this type are most common in the south and west of North Yorkshire and are almost absent in the northeast (Fig. 9). They are also relatively common in the Vale of York and the southern Dales. Most of the three-cell houses were built in the period between 1650 and 1739; thereafter they were superseded by alternative forms.

Fig. 8 Lobby entry form. Stonebeck Up, Nidderdale, late 17th century. Lobby is formed by a plank screen facing the main central doorway. In this example there is a fireplace in the parlour and in a rear room.

Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 9

10 In the highland regions change was already taking place in the 16th and 17th centuries in the plan of the longhouse, bringing it closer to that of the two-storey farmhouse with or without a through hearth passage (Harrison and Hutton 1984). Modifications in housing materials and attempts at variation in decoration were beginning to bring about a new look to the rural housing landscape of the region. The proximity of Holland led to a trade in bricks and pantiles which increasingly were being used for roofing in East Anglia, Lincolnshire and the eastern parts of the Vale of York by the end of the 17th century (Harrison and Hutton 1984; Cook 1982). These changes reflected developments in the practical arts, such as house building as well as agriculture, and these changes were well underway before the 17th century. The process gained pace because of rapid population expansion and resultant need for new supplies of food. Part of this was contingent on the creation of new farm units and the 18th century was notable for the almost 2,000 acts of enclosure that occurred in the century (Cook 1982). By these means, what had formerly been open field arable strips were recast and merged into more nearly rectangular enclosed fields, farmed as blocs by independent farmers. These enclosures were characterized by the stone walls that have come to mark out the landscape of Yorkshire, popularized more recently by the television adaptation of the books of James Heriot.

11 The consequence of this transformation on cottagers and small holders was acute. The rural labouring class which had been able to supplement wages by keeping livestock on the wasteland now had these rights taken away thus pushing many into poverty. The poor had to be accommodated through the system of outdoor poor relief within the parishes in which they resided, a charge that fell on the landlords. Not surprisingly there were many efforts to dislodge the poor by permitting their cottages to become ramshackled (Cook 1982). As food prices rose in the second half of the 18th century, impoverished people were forced into even greater depths of despair and many had little choice but to leave for the cities or to emigrate. As a result, an even wider gulf was created between the living standard of people with land, and those without. Even within the dwelling of the prosperous farmer life changed as the servants were separated from the family in matters such as dining. Successful farmers began to put on airs, a behaviour that was recorded and scorned by observers of the day, people like William Cobbett (Cook 1982).

12 Not all farmers prospered under this system. Small farmers seldom owned the land they cultivated and when farm landlords decided to amalgamate several farms, the tenants were squeezed out of existence. In their place landlords could initiate larger scale farming using the new technique of convertible husbandry. This practice employed crop rotations of mixed grains with restorative root and clover, combined with livestock. Selective breeding of livestock permitted productivity gains. One of the transformations that occurred with this system was the dispersal of farmsteads out on the landscape away from the clustered farm villages. Consequently, new houses and barns were built according to new principles and ideals. As this process occurred it led to changes in the old village farmhouses causing many to be divided into two or more cottages. Not all villages ceased to house the farmers; in northern areas, the farm village remained little altered and the longhouse form persisted and was still being constructed into the 19th century. In many cases, however, these ancient forms were transformed to fit new ideals, especially as farm yards were laid out into regular rectangular plans with functionally distinct building units forming the plan—all executed using local carpenters and materials (Cook 1982).

13 The surge toward Palladian symmetry and order which underlay many of the ideals promoted during the 18th century for the plan of the farmstead affected the farm house as well (Cook 1982). The facade of the dwelling, regardless of what happened behind it, was designed in terms of a classical order, and the proportions of the storeys ideally conforming to classical Greek and Roman ideals. Through the medium of books and prints, these ideals penetrate rural England. Examples of this genre are William Halfpenny’s Twelve Beautiful Designs for Farmhouses (ca. 1730) and Isaac Ware’s Compleat Body of Architecture (1756). Despite these processes, old traditions remained in many areas of the north. In some cases, however, even traditional dwellings yielded to modest attempts to graft new fashions onto the facade in the form of door surrounds and the like, interpreted by a local carpenter from a print source. Where the longhouse was customary, the farmer’s quarters might now exhibit an orderly disposition of doors and windows in an otherwise scarcely-changed interior, even when this meant not being able to precisely align the door in the centre of the facade.

14 For those with means to erect a new house on their land, it was possible to emulate the many variants of the Georgian dwelling which represented the dominant fashion of the middle and late 18th century. This house, with its rigid rules of internal and external symmetry, its provision of informal and formal spaces within the floor plan and its much more self conscious separation of inmates by gender and class, represented the most pronounced watershed between post medieval material culture and what we now think of as the beginning of modernity. For the first time prospering farmers, small holders and petit bourgeois townspeople were able, through the houses they built, to demonstrate their own sense of social and economic accomplishment. They did this by mimicking the stylist detail and use of materials such as brick, as employed by the social elites.

15 Thus it was that by the third quarter of the 18th century, when the Chignecto Yorkshire emigrants were departing for Nova Scotia—many of them the victims of the dislocating forces just discussed—we might expect that they would have been conscious of the changes occurring in house building ideals in their home region. Furthermore, we might suppose that the social coordinates of these changes, however subtle and nuanced, also would not have escaped notice, even if their experiences with these newer housing forms may have eluded them. On this latter point, however we have no evidence by which to assess their perceptions. Nevertheless, if we accept this notion, it may well be the case that when it came time to create housing for themselves in Chignecto, they would have experienced a tension between the propensity to reproduce that which was familiar and traditional, or reject it in favour of forms that reflected the latest fashions and made a social-material display.

The Arrival of a Yorkshire Colony in Chignecto

16 The Yorkshire families that embarked at Hull and other English ports for disembarkation at Halifax and who then travelled by coastal schooner or overland to the Fundy marshlands were a comparatively prosperous group of emigrants, certainly in contrast to the Highland Scots who landed on the Antigonish shore in the same period.5 Many of these Yorkshire settlers arrived with some means. Those who had been tenant farmers in Yorkshire would have accumulated some wealth and would have realized profits from the sale of “improvements” and livestock. As a result, they were quickly able to purchase sizable existing farms, including dyked marsh, cleared uplands and wooded uplands. It is not surprising, then, that they were able to fashion a landscape with the appearance of established affluence before 1800. Unlike other newcomers in other parts of eastern North America there was no large-scale exercise of carving out tiny clearings in an oppressive forest, with the associated experience of small log lean-tos or rude cabins that mark the pioneer experience of settlers in the Ontario bush or the American Appalachian frontier.6 As a result, essayists John Robinson and Thomas Rispin, visitors to the region in 1774, could report that the Harpers occupied a model farm with fine cleared land and that they lived in a well furnished manor house. Even if Harper was exceptional, it reminds us again of the need to be aware of the context of the first generation’s shelter experience, a context related to wider issues of property beyond four walls, and an emphasis that forms this paper’s central focus.

17 In the wake of the French and Indian War, with the French no longer a military power on the continent and with their Indian allies diminished in the east, a vast array of land became available on the North American colonial frontier. This included, in addition to Nova Scotia, northern New England, western Pennsylvania and the Carolina Piedmont. The ongoing presence of Indian populations both east of, and adjacent to, the Proclamation Line made western American land less desirable initially, whereas a familiarity with adjacent Nova Scotia meant that some 7,000 New Englanders were attracted north from overcrowded agricultural townships.

18 The specifics of these settlement schemes and the ways that land jobbers became involved in the attempt to populate the settlements provide the backdrop for the presence of Yorkshire emigrants in Chignecto. In what is now the Canadian Maritimes, groups of New Englanders (and some Pennsylvanians) occupied and re-platted much of the land that was cleared a century earlier by the Acadians who had been dislodged and dispersed by the British following 1755.To the extent that many in this replacement population were American settlers or “planters” who occupied lands in the upper Annapolis and Minas areas, such as at Cornwallis and Horton, American architectural forms were reproduced in these settlement pockets. These land division and settlement models echoed earlier American planting schemes. These included use of proprietary town schemes like those promoted in northern New Hampshire under the Royal Governor Benning Wentworth in the 1760s, where agents recruited settlers to stock ranges of land parcels. Examples in Nova Scotia include Horton Township on once-Acadian marshlands in the Minas Basin (Wynn and McNabb 1984), as well as broader efforts to set up Francklin Manor, and the settlements of the Pennsylvania Company at both Pictou and at the “Bend” of the Petitcodiac River, the present-day Moncton (Bailyn 1987; Bumstead 1994).

19 Yet the first wave of American settlers found Nova Scotia far less appealing than they had hoped, and many returned to take up lands in western Massachusetts and other more settled American regions with better infrastructure and established markets and where they might be closer to kith and kin. Nevertheless promoters of these schemes still needed settlers if their investment was to become profitable and, at another level, for the colonial authorities’ geopolitical objectives to be realized.

20 The recruitment of Yorkshire tenant farmers by agents for Nova Scotian land schemes aimed to stock a territory already platted, at least on paper, with a rudimentary framework of forts and ports in place. At a time when American colonial regions were preoccupied with thoughts of rejecting British links, this northern extension of New England was tied more closely to British colonial development through immigration, a process that would continue with waves of Loyalist settlers in the coming decades. At Chignecto those British links would be severely tested very quickly, as the area surrounding Fort Cumberland suffered serious damage during the Eddy Rebellion of 1776. At least twelve “Gentlemen’s Estates” were burned. The rebuilding process would have taken a while, framed as it was for at least a dozen years by the spectre of arson and compounded by hard feelings among those who had taken opposite sides in the rebellion (Clarke 1995). Barns and other structures for the necessities of agricultural life would have required immediate attention; thus it is likely that any “new” houses would have come later, and likely more quickly for those who were more successful.

21 So it was that these Yorkshire settlers, from an array of long-settled places, came into an established context, not a blank space. Their common faith—most were Methodists motivated in part to seek a haven for their religious dissent—would have meant there were early efforts to build a place of worship. They largely settled on the upland ridges, not the marsh itself, and this topography inevitably created some sense of loosely connected street villages—farmhouses stretched north from Fort Cumberland, toward the hamlets that became Mount Whatley and Point de Bute. They did not, however, typically replicate the fieldstone facade as the signature look of their buildings, as may have been the norm in Yorkshire. Fieldstone was less available, and quarried stone—something that the military engineers of the nearby forts might procure—initially exceeded the reach of those on the surrounding farmscapes (Martin 1990).

22 Our attention now turns to Chignecto to examine examples of houses that have been understood to be examples of “Yorkshire vernacular” by local interpreters. In looking at them we will ask: are these dwellings authentic versions of the Dales’ houses, or are they attempts by immigrants, after a generation of hard frontier struggle, to assert the owner’s social achievements by means of replicating or mimicking architectural “status” models they could not have attained in the homeland? Is it possible that the scale and form adopted were the appropriate new symbols of attainment, or progress, and that Chignecto Yorkshire settlers were more concerned with measuring new world contemporary norms than they were with replicating, albeit a generation later, forms from their recent Yorkshire memory? Was it simply that, although conscious of the high-styled architecture of the “big house” of the Yorkshire estates (the pinnacle of which was Vanbrugh’s unattainable Castle Howard), the three-bay or five-bay brick Georgian house associated in their memory with the successful farmer or the minor rural gentry, might have become attainable and reproducible in this new world?

Surveying the Extant Evidence on the Landscape of Chignecto

23 No exhaustive and reliable field survey exists for the early housing of the region, let alone for the 18th century Yorkshire colony of Chignecto. Locally there are many extant dwellings that are attributed to the families that made up this colony.7 Our observation is that many of these buildings actually date to the second quarter of the 19th century and as such were probably built by second or even third generation descendants of the original Yorkshire emigrants. There are, however, a few extant dwellings whose histories are better documented and for this reason we will focus on assessing what they reveal about the process of remaking the built landscape in the new world. Three case examples have been selected for analysis: the Chapman House, the Keillor House and one of the Trueman family houses. Each of these cases helps map a pattern of cultural transfer and change.

24 Chapman House, located on the Fort Lawrence ridge is believed to have been built shortly after 1799 (Fig. 10).8 William Chapman arrived at Cumberland in the spring of 1775 with a wife and eight children. He soon purchased a large block of upland and marsh above Fort Lawrence on which he settled. The fact that he was able to purchase a large parcel of land suggests that he brought some capital with him. The family is assumed to have formerly resided in Hawnby Hall, a house in the village of Hawnby near Thirsk.9 The brick house that Chapman built for himself in Chignecto is one of the few brick houses of the Yorkshire colony that still stands, and it provides some insight into the nature and form of dwelling that may have been erected by other of their fellow emigrants across the Chignecto region.

25 Chapman House is a two-storey gable roof dwelling measuring 39 feet by 28 feet. In plan, the house consists of four identically placed rooms on each floor, divided by a centre hall and stair (Wallace 1976). The front rooms are significantly larger than the rear rooms and would have served as parlours and lesser rooms respectively. A service ell encompassing a kitchen was set perpendicularly on the rear of the house. The exterior appearance of the dwelling reveals a considerable concern to produce a fashionable facade. Constructed of bricks made and fired on the property, these have been laid in flemish bond with the darker burned headers contrasting with the lighter red stretchers. Maintaining a carefully worked symmetry of openings, considerable attention was paid to door and window details. Window sills and the keystones set into the brick lintels were cut of sandstone, quarried at Wallace, another Yorkshire settlement located several miles to the northeast on the Northumberland Strait. The main door had a four-light transom window and half sidelights set so as to match the height of the window sills. The second floor window above the main door was also carefully detailed with sidelights creating a Palladian impression set beside the common six over six window sash. Two opposing chimney stacks were set within the end walls providing fireplaces in each of the big rooms on each floor.

Fig. 10 Chapman House, built ca. 1799, near Fort Lawrence, NS. (Photo by Peter Ennals, 2006). The ground floor plan is nearly identical to the second floor plan. Plan drawing adapted from those in Wallace 1976.

Display large image of Figure 10

26 The overall impression created by this dwelling is one of substantial economic achievement, a consciousness of prevailing tastes and considerable skill in construction execution. The dwelling would not be out of place among the houses of prospering farmers and petit bourgeois townsmen of the day in old England, or New England. As such it is a telling statement of Chapman’s accomplishments. But in the absence of some reliable evidence of what Hawnby Hall was like, as a presumed precursor of this family’s Yorkshire housing, it is difficult to measure the extent to which, in building it, Chapman was attempting to reproduce a familiar housing presence in Chignecto. The fact that the Chignecto house adopts the Georgian plan clearly indicates that he was breaking from the old traditional modes of housing described earlier. This is hardly surprising given that the house was constructed some twenty-five or more years after Chapman arrived in Chignecto. By this time his connections to his homeland were undoubtedly dimmed by time and distance, and even if nostalgia were a motive for his selected housing form, there were other more accessible styles and forms in the region to be considered by those seeking to make a personal statement through the house form. Certainly the fact that the house was constructed of brick rather than stone suggests that Chapman might be emulating a more North American dwelling. By 1800, brick was the most common building material used to render good substantial vernacular housing in the new Republic to the south and throughout many parts of the remaining British North American colonies as well. Moreover, the careful, almost academic, symmetry and execution of the facade suggested that Chapman had referred to pattern books for inspiration. Simply put, this house was anything but a throw-back to Yorkshire, but rather was a clear case of reproduction in an American vernacular Georgian architectural style. One might have thought that in this part of Nova Scotia, in which memories of the Colonel Jonathan Eddy’s abortive flirtation with the American Revolution still complicated many personal relationships, such an American dwelling might seem paradoxical, especially given the public professions of British loyalism after many of Eddy’s sympathizers vacated the region.10 Yet this seems to be the inescapable reading of this house. Thus in the quarter-century after leaving Yorkshire, Chapman and his kin became part of the settler society of the Nova Scotia/New Brunswick borderland. Like many in this setting, the family lived on their farm holding, rather than in villages, and they embraced the styles and tastes that gave form to a new landscape. Perhaps as people who had made a break from a setting that, at the time of leaving, offered few prospects, they happily put distance between memories of home and its material forms—forms that had literally come down from medieval times. At the dawn of the 19th century, a new house built in the most fashionable style then current, constitutes an affirmation that they had broken from the old world. The picture of the Chapman family and its housing must be set against that of another Yorkshire family whose chronology and experience is in many ways similar and indeed intertwined.

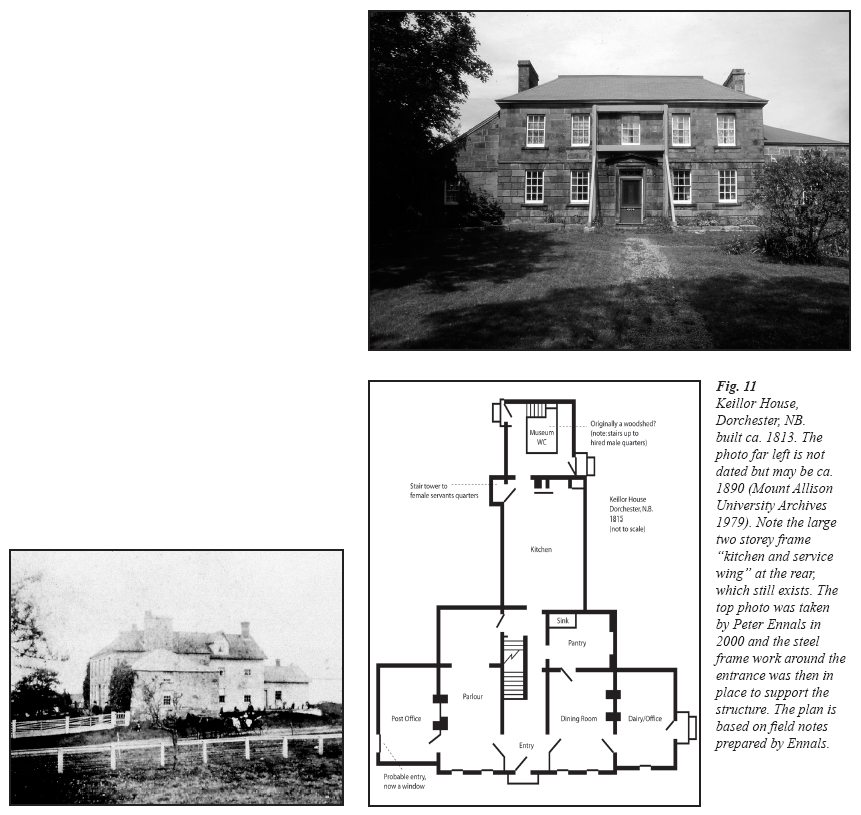

27 Thomas Keillor came to Nova Scotia from Skelton, Yorkshire, in 1774 and settled initially near Fort Cumberland. His son John moved to Dorchester NB, in 1786 and became one of that village’s first and most prominent figures. Keillor House (Fig. 11), located in Dorchester is generally believed to date to 1813 and was built by John Keillor, who like his father had stone masonry skills.11 The main dwelling is a two-storey pile, with attic block built of cut stone with rustication, flanked by more or less symmetrical “lean-to” wings. The main facade is symmetrical with a rather simple door with transom light, flanked by two windows on each side of the door. The roof is a truncated hipped with a large flat centre deck. To the rear is a substantial two-storey ell with gable roof. Two large multi-flue chimney stacks are located on the side walls of the dwelling between the main house and the wings. The centre hall plan of the main floor separates a parlour on the left side, which probably opened onto a small bedroom at the back; on the right, a similarly scaled parlour gives access to a pantry at the back. These rooms were extensively updated probably in the 1840s to conform to the fashion of the day so that they now present a double parlour on both sides, each of which has fireplaces and plaster detail that is characteristic of the early Victorian period.12 The two wings are believed to have served as a post office on the westerly side and a dairy or still room on the easterly side. Each of these wings probably had a separate entrance on the side walls, which is retained today in only the easterly wing. On the main floor of the ell was a large kitchen with a substantial cooking fireplace and oven located on the end or the north wall. Beyond this was a woodshed. Female servants accessed their quarters above the kitchen by a tight circlular stair case attached as a tower to the western exterior wall of the ell.13 The space above the woodshed probably served as quarters for male servants. Family bedchambers occupied the spaces over the main parlours and were accessible by the main hall staircase.

28 Like Chapman House, this house is remarkable for the quality of its materials and the studied execution of its architectural detail. Like Chapman, it is evident that Keillor was self-consciously reproducing a dwelling that reflected his having succeeded in this place. But in this case Keillor chose an architectural idiom of his homeland as the expression of that achievement. Indeed, through its use of cut stone on the central facade, its scale and proportions, this house, replicated a form of middle-class dwelling being erected in the towns of rural Yorkshire through the last decades of the 18th century. How familiar John Keillor was with this idiom is open to question. The evidence suggests he was probably born about 1759-60 and emigrated with his father in 1774 (Machum 1967). He was therefore barely a teenager when he left Yorkshire, and this dwelling was built when he was about 54 years of age. Is the dwelling the product of a young boy’s memory, or is it the product of a more studied attempt to reproduce a style of dwelling using pattern books or other guides? Was he indulging a strong sense of personal nostalgia, or was this a conscious attempt to employ accepted icons of social status that was still very British in its imagery and detail? Was it something else entirely? Whatever the reality, we suggest that his was a response that followed the pattern of at least a few members of the colonial society emerging in this place. Significantly, the Dorchester area could count Loyalist Amos Botsford’s house of 1783 (located on Dorchester Island and now demolished), the Bell Inn (a.k.a. Hickman House, ca.1800) and Chandler House (1832) in addition to Keillor’s dwelling. Similarly there were a handful of stone houses located on the Fort Cumberland Ridge, one of which was Thomas Keillor’s house of about 1778 but, surprisingly, only one of these survives. While supplies of stone may have been a problem, there were stone quarries developed nearby and during the middle decades of the 19th century the region had a healthy quarrying industry both in building stone, but more particularly in grindstones, most of which was exported (Martin 1990).

29 In the face of the evidence, one concludes that the general abundance of timber and, later, milled lumber, and the rise of a variety of woodworking trades including shipbuilding, conferred on the region a propensity to work in wood. The development of these skills provided those seeking to create new housing with a remarkably inexpensive and impressively manipulable medium for the execution of dwellings at all scales and design aspirations. Not surprising many of the descendants of the Yorkshire migration had adopted this mode of construction by the first decade of the 19th century, if not earlier. We turn now to explore an example of this pattern.

Fig. 11 Keillor House, Dorchester, NB. built ca. 1813. The photo far left is not dated but may be ca. 1890 (Mount Allison University Archives 1979). Note the large two storey frame “kitchen and service wing” at the rear, which still exists. The top photo was taken by Peter Ennals in 2000 and the steel frame work around the entrance was then in place to support the structure. The plan is based on field notes prepared by Ennals.

Display large image of Figure 11

30 The house that came to be known as Westover (Fig. 12) was located on land adjacent to the site of Prospect Farm, home farm to the important Trueman family.14 Westover was constructed for Thomas Trueman in 1842 and as such represents a phase of house building by descendants of the emigrant generation. It was constructed of wood, and its exterior detail was finely executed. Much more modest in its proportions than the brick house, it was built in accordance with the emerging regional vernacular which was becoming commonplace in the second quarter of the 19th century. A one-and-one-half-storey dwelling, it presents a symmetrical facade capped by an axial gable roof. In plan, the house consisted of two parlours on the front flanking a central hall. Behind these rooms were two other rooms which were variously used as bedrooms and as service rooms fitted to the families needs (e.g., dairy, scullery). On the upper level additional bedrooms were created. A kitchen ell at the rear of the house provided a large service wing.

31 Of significance was the application of neo-classical exterior detailing to the facade. These consisted of vertical corner board or pilasters with capitals, return eaves and a particularly well-detailed enclosed entrance with classically inspired window and sidelights. The cladding was horizontal clapboard. All of this detail suggests that one of the generally available American pattern books was used to guide the builder in the execution of the house.

32 If this case is typical of a pattern in Chignecto, it is clear that by the time the post-emigration generation was ready to build houses for themselves, notions of an earlier Yorkshire dwelling pattern were no longer part of their imagination or design sense. Rather these were people of this colony and continent, and their sense of what was appropriate was influenced by the norms of the greater settled northeast of North America. As we have argued elsewhere, this dwelling form acquires a cultural currency across this broader space, albeit rendered in brick and stone in some regions, in wood in others and with many local flavours as interpreted by the local carpenter’s art or the homeowners predilection. What is important is that the transition from the old world to the new was largely completed, and while from time to time a new emigrant or colony of new emigrants might for a time try to reassert a familiar folk pattern following their arrival, the weight of a North American vernacular soon permeated these new groups’ way of building houses as well.

Conclusion

33 The evidence that we can draw on for ascertaining the house making experiences of Yorkshire settlers in Chignecto in the last quarter of the 18th century is almost non-existent. Qualified by the keen awareness that we lack an array of extant or archival building records, we have gained some insight into the tension between the past and the future, between looking backward and moving forward. In this rebuilding of lives across an ocean, we have favoured a notion relating to the human nature of immigrants, namely that some of them tend at the end of their lives to indulge in a certain homeland nostalgia and yearning that leads to the reproduction of these old world icons, however muted and outof-fashion they may have become in the intervening time. This propensity to return to modes that had largely passed out of cultural currency happened only sporadically, it is worth noting, and we do not present it as the overarching model.

Fig. 12 Westover, the Thomas Trueman house built in 1842, near Point de Butte, NB. The left photo (taken by Peter Ennals) shows the house in 2006. The right photo (taken by Reginald Porter probably in the mid-1970s (Mount Allison University Archives 8036/21)) shows the fine details of the front entry, much of which has disappeared in a more recent renovation.

Display large image of Figure 12

34 We could hypothesize that if there were dozens of two-storey stone or brick houses by the early 19th century, indicating a statistically dominant house type that became the vernacular of the Yorkshire group, then these buildings fell victim to at least two processes. One hypothesis would be that the quarrying of stone and the making of brick was comparatively expensive and/or in the case of brick, of poor quality, and after some passage of time inhabitants became tired of living in drafty, damp and cold shelter.15 Building in wood was simply more practical and the many examples of this building technique nearby showed the way. A second hypothesis could be the overwhelming desire to move on to a more fashionable style of house: one that was built of wood and rendered in the neo-classical mode, such as that built byThomas Trueman. Examples of this “style” were widespread in the region and, more broadly, in New England with which Nova Scotia and New Brunswick interacted culturally throughout the period. Certainly, a survey of housing on both flanks of the Cumberland basin suggests that many took advantage of 19th century prosperity in shipbuilding, shipping and maturing agricultural economies to build, or rebuild, houses that reflected what were by then a progression of contemporary stylings.

35 We are left, then, with a regional landscape that even today is dotted with familiar names of people who are descendants of those 1,000 Yorkshire folk that came in the 1770s. And, we are left with their graveyard cemetery markers, some in the Methodist churchyards established in the 1780s and 1790s, others in farm corners. If these names echo to Bilsdale or Hawnby, or many other rural Yorkshire settings, we need to be mindful that those old country landscapes were not static, but that they too went through a transformation. The dynamics of material progress occurred there as well as in the Canadian Maritimes. A fuller study would be needed to track the parallel trajectories of farmers who stayed in Yorkshire and modernized, as well as the material circumstances of those less fortunate, who ended up as farm hands in rented cottages in farm villages, or moved to town and city life. This is not to detract from the insights that can and do come from Chapman, Keillor and Trueman, nor from the testimony of houses that have survived for two centuries in a world that increasingly discards material objects after a decade of use, let alone a lifetime. What is clear is that early Chignecto settlers from Yorkshire looked back to their homeland for inspiration when the time came to fashion a new settlement landscape, but these memories soon faded and not surprisingly, within a generation, their descendants were moving forward with house building idioms that mirrored a contemporary mainstream. Ethnicity, or folk memory, if that be it, was surprisingly transient in so far as house building was concerned, and this pattern is likely to characterize the experience of many other settlers groups in North America.

REFERENCES

Bailyn, Bernard. 1987. Voyagers to the West - A Passage in the Peopling of America on the Eve of the Revolution. New York: Knopf.

Barley, Maurice W. 1961. The English Farmhouse and Cottage. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Brunskill, Ronald W. 1971. Illustrated Handbook of Vernacular Architecture. London: Faber and Faber.

Bumstead, J. M. 1994. 1763-1783: Resettlement and Rebellion. In The Atlantic Region to Confederation, ed. Phillip A. Buckner and John Read, 156-83. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Caffyn, Lucy. 1986. Worker’s Housing in West Yorkshire, 1750-1920. Royal Commission on Historical Monuments of England, Supplementary Series 9. London: HMSO.

Clarke, Ernest. 1995. The Siege of Fort Cumberland, 1776. Montreal: McGill-Queens University Press.

Cook, Olive. 1982. English Cottages and Farmhouses. London: Thames and Hudson.

Cummings, Abbott Lowell. 1979. The Framed Houses of Massachusetts Bay, 1625-1725. Cambridge: Belnap Press.

Ennals, Peter and Deryck W. Holdsworth. 1998. Homeplace -The Making of the Canadian Dwelling Over Three Centuries. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Fenton, Alexander and Bruce Walker. 1981. The Rural Architecture of Scotland. Edinburgh: John Donald.

Gentilcore, R. L. 1956. The Agricultural Background of Settlement in Eastern Nova Scotia Annals of the Association of American Geographers 46 (4): 378-404.

Giles, Colum. 1986. Rural Houses of West Yorkshire, 1400-1830. Royal Commission on Historical Monuments of England, Supplementary Series 8. London: HMSO.

Grant, I. F. 1961. Highland Folk Ways. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Harrison, Barry. 1991. Longhouses in the Vale of York, 1570-1669. Vernacular Architecture 22:31-39.

Harrison, Barry and Barbara Hutton. 1984. Vernacular Houses in North Yorkshire and Cleveland. Edinburgh: John Donald.

Machum, Lloyd A. 1967. The Dorchester Keillors. Dorchester: Westmorland Historical Society.

Martin, Gwen L. 1990. For the Love of Stone, Volume 1, The Story of New Brunswicks’ Building Stone Industry. Fredericton: New Brunswick Department of Natural Resources, Miscellaneous Report 8.

Mount Allison University Archives. Sackville Art Association fonds, 8036/2, 8036/21. Local Architecture, Annual Spring Show, May 13-June 2, 1979, Owens Art Gallery.

Mount Allison University Archives. Marshland - Records of Life on the Tantramar. http://www.mta.ca/marshland/index.htm.

Mercer, Eric. 1975. The English Vernacular House: A Study of Traditional Farmhouses and Cottages. London: HMSO.

Noble, Allen G., ed. 1992. To Build in a New Land- Some Nineteenth Century Ethnic Landscapes of North America. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Peate, Iowerth C. 1946. The Welsh House. Liverpool: Brython Press.

Robinson, John and Thomas Rispin. 1774. Journey Through Nova Scotia: Containing Particular Account of the Country and its Inhabitants. York, U.K.: C. Etherington.

Royal Commission on Historical Monuments. 1987. House of the North York Moors. London: HMSO.

St. George, Robert Blair. 1988. Material Life in America 1600-1860. Boston: Northeastern University Press.

Stokes, Peter John. 1967. Unpublished Restoration Architects’ Report on the Keillor House. Dorchester, NB: Keillor House Museum.

Tantramar Heritage Trust, 1772-1775. Yorkshire Immigration to Nova Scotia Partial Listing of Yorkshire Villages of Origin. http://heritage.tantramar.com/villages.html.

Trueman, Howard. 1902. The Chignecto Isthmus and its First Settlers. Toronto: W. Briggs.

Trueman, William Albert. 2000. Round a Chignecto Hearth. Summerside, PEI: Sin Twister Publishing.

Upton, Dell, ed. 1986. America’s Architectural Roots: Ethnic Groups That Built America. Washington: Preservation Press.

Wallace, Arthur W. 1976. An Album of Drawings of Early Buildings in Nova Scotia. Halifax: Heritage Trust of Nova Scotia and the Nova Scotia Museum.

Wynn, Graeme. 1979. Late Eighteenth Century Agriculture in the Bay of Fundy Marshlands. Acadiensis 8 (Spring): 80-89.

Wynn, Graeme and Debra McNabb. 1984. Pre-Loyalist Nova Scotia. In Historical Atlas of Canada. Vol. 1, ed. R. Cole Harris and Geoffrey Matthews, Plate 31. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

NOTES