Sense of the City

Cynthia HammondConcordia University

Venue: Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montreal

Curator: Mirko Zardini

Designer: Atelier In Situ, Tillett Lighting Designs (light), Orange Tango (graphic)

Duration: 25 October 2005 to 10 September 2006

Accompanying publication: Zardini, Mirko, ed. 2005. Sense of the City: An Alternate Approach to Urbanism. Montreal: Canadian Centre for Architecture and Lars Müller Publishers.

ISBN: 0-920785-73-5

(Canadian Centre for Architecture)

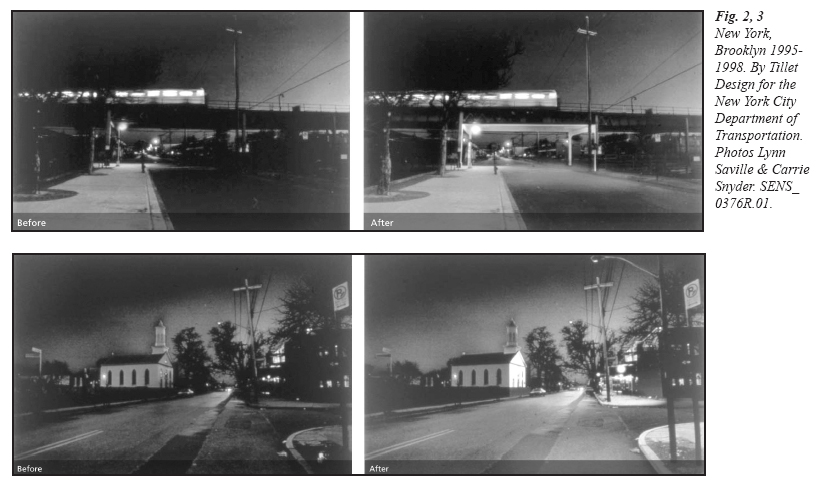

ISBN: 3-03778-060-6

(Lars Müller Publishers)

Publisher’s address:

Canadian Centre for Architecture

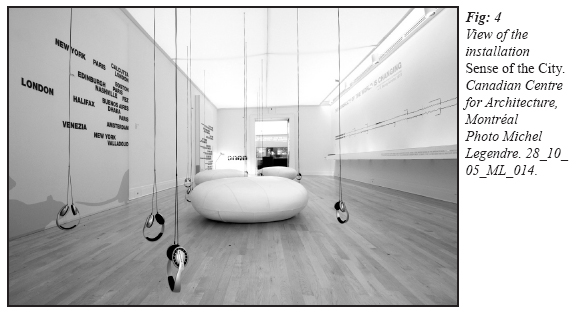

1920 Baile

Montreal, Quebec

Canada H3H 2S6

Price: $58.00 CDN (soft cover only)

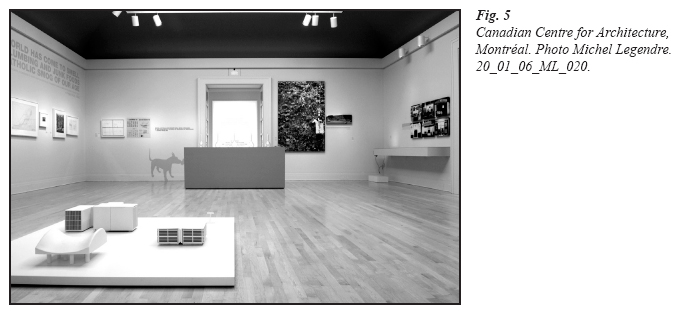

I experience myself in the city, and the city exists through my embodied experience. The city and my body supplement and define each other. I dwell in the city and the city dwells in me. Juhani Pallasmaa (2005, 32)

1 The current exhibition at the Canadian Centre for Architecture, Sense of the City, has a heuristic as well as a didactic purpose. Mirko Zardini, curator and Director of the CCA, suggests that through the exhibition’s key themes “we might learn to move around the city in a different way, in a manner that depends less on vision and more on the other senses, emulating the animals who increasingly share our cities with us.”1Accordingly, the exhibition addresses the multiplicity and heterogeneity of human, animal and insect sensoria alongside the ways individual cities reveal their mutability, from cold to warm, from continuity to innovation and from day to night. The exhibition explores differences in aural and olfactory spaces, showing them to be peculiar not only to each city, but also to moments within a city’s past. Sense of the City further reminds us of the formative contingency of geographical specificity upon a city’s character, its appearance, labour history and material culture.

2 The philosophical emphasis within Sense of the City on the varieties of sensory and subjective experience directs the viewer towards the haptic. Eschewing the traditional architectural emphasis upon the façade and the urban planner’s dependence upon the bird’s-eye view, Sense of the City looks instead to the sky, puts its ear to the ground and sniffs out the tracks of our often-unwanted colocataires: garbage trucks, cockroaches, dark alleys and municipal bylaws. Fundamentally, the question driving the exhibition is: How do we, as humans, engage with, understand and know the city? The answers depend heavily, in a curatorial sense, upon the interface between sight and site, touch and surface, and the specificities of smell and noise within a shared habitus. Rather than a sequence of aesthetic misfires and successes, the city in this exhibition is privileged, refreshingly and engagingly, as a space of human responses. There are moments of humour, lyrical delight, curatorial daring and a worthwhile celebration of the quotidian and the ordinary.

3 The famous essay—and declaration—of Raymond Williams (1989) that “Culture is Ordinary” proposed in 1960s Britain a radical expansion of the term “culture.” Wishing to incorporate within recognized scholarly fields (art history, literature and music, for example) an understanding of the social relations that helped to produce them, Williams argued that culture is a fundamental aspect of all social groups and that it is inherently political. Denial, he explained, of the culture of Welsh farming communities in favour of the culture of Cambridge tea rooms privileged and preserved the dominance of the ruling class. Thus, Williams concluded, the writing of scholarship and the curating of exhibitions about culture were integral aspects of the mechanism by which those dominant classes reiterated and maintained their superiority.

4 Since Williams’s early work, material culture studies have undergone several transformations and expansions of their own but, according to Geismar this field still fundamentally takes up the “close examination of material forms and social relations in which they are embedded” (2004, 43). What insights, then, about the varieties of urban, material culture does Sense of the City offer in relation to understanding formative social, political and economic conditions? How does it explore and critique regimes of urban value? How does the privileging of the haptic senses within Sense of the City, in relation to the objects on display, teach visitors something new about the material culture of cities? Set up as a series of thematic encounters, the exhibition considers the nocturnal city, the seasonal city, the sounds, surfaces and air of the city—themes which are echoed and expanded on in Zardini’s (2005) accompanying publication, Sense of the City: an Alternate Approach to Urbanism. Loosely structured upon the traditional identification of five senses, the exhibition also contests this purported sensorial order. Sense of the City and its accompanying publication may be understood as critical contributions to the growing body of interdisciplinary scholarship that takes the city as a primary locus of investigation (Borden and Rendell 2002; Watson and Gibson 1995; Hayden 1995; Leach 1997). As such, however, they face the same methodological and epistemological hurdles facing such scholarship and, accordingly, reveal the ongoing challenges and rewards of interdisciplinary inquiry. While the exhibition’s phenomenology rests uneasily at times with its embrace of material culture and evocation of difference, it must nonetheless be applauded for asking how the city is made—in and through our daily, sensual and affective lives.

5 Visitors enter the exhibition through a darkened, matte-black tunnel, accompanied by the recorded sounds of various cities. A single-channel video projection by Alain Laforest—Montreal, 21 June, 12am-25 October, 12am 2005—in the adjacent room represents a time frame of four months. Filmed at different times of day (dawn, dusk and night), all that is perceptible at times is a soft and tiny mobile bluish-grey bird cutting an occasional arc. Other times it looks as if Laforest filmed small sections of Turneresque clouds of rose, ochre and periwinkle and set them gently in motion. Devoid of human presence and lacking any narrative other than the passing of time, the beautifully-edited result is a rubric for the exhibition as a whole that introduces themes of mutability, specificity and pleasure, gently setting aside architecture and urban planning as preferred criteria for understanding the city. It also proposes something about the nature of the experiences visitors are about to have: reflective, contemplative, solitary.

Fig. 1 Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montréal. Photo Michel Legendre. 27_10_05_ML_009.

Display large image of Figure 1

6 An enormous black silhouette of a rat looms on one of the low-lit, bluish walls of the first installation (Fig.1) while silhouettes of cockroaches, large spiders, butterflies, bats, cats and dogs also animate the surfaces of this room. Here, the visitor is introduced to the notion that the senses are neither given, nor universal, not even the standard five accepted as given in Western culture. We are told that the hearing capacity of rats lies between 1000 and 90,000 Hz, but the comparative ramifications of this fact are untold. (The book accompanying the exhibition does tell me that the human range of hearing is limited to between 20 and 20,000 Hz.) More useful is the information that ants are able to sense minute disturbances through a few centimetres of earth. Philosophically, the most engaging aspect of this room is its proposition that animal, insect, even robot perceptions of habitats, including urban habitats, are as worthy a subject for consideration as the perceptions of human beings when rethinking the urban experience. To foray into recent theoretical territory which deconstructs the humanist othering of “other” species in its privileging of (even the benevolent) human, is to set a quite brave tone of inclusivity and criticality, especially for a museum dedicated to the built environment.2

7 The challenge is how to register such differences and presences in a way that does not defer to vision or other familiar “regimes of value” to quote Graburn and Glass (2004). The deliberately low lighting in this section of the exhibit may have been too subtle a gesture of opposition to the “scopic regime” (Rose 2001) for people struggling to make out texts and shapes during my visit. Delightfully, however, the silhouettes of ants and animals follow us through the exhibition as a whole, turning up above, beside and under vitrines and displays, reminding us of what is so easily forgotten in urban contexts: that we share this world with a multiplicity of species.

8 The “Nocturnal City” complicates vision as a prime or dependable vehicle for exploring urban space. Velvety, barely-legible photographs of Berlin streets at night by John R. Gossage and “audio-tactile” guides to the city of Bologna, Italy explore the ambivalence of the invisible city; we are not permitted to muse only upon its visual beauty, nor are we expected to embrace Manichean oppositions of dark and light, evil and good. Images of Nazi night-time rallies and light spectacles known as “cathedrals of light” are hung alongside large-scale reproductions of cities plunged into darkness, either through power failure or for self-protection as in the case of London during the World War II blitz. A 2004 poster (TBWA/Chait/Day) produced by the Joe Torre Safe at Home Foundation brings to mind images of bodily safety. The poster depicts a badly lit, rundown residential neighbourhood. The image indicates that “it’s safer here” on a dingy sidewalk “than here” in the only brightly-lit area of the image—a second story window. In a rare moment of consideration of specific embodied differences among humans, the exhibition addresses the physical safety of women and children and points to the vacuity of civic measures to prevent violation and aggression of such bodies.

9 Designer and environmental psychologist, Linnea Tillett’s work on urban lighting design is one of the strongest contributions to the exhibition. Tillett writes that “instead of looking at how pedestrian lighting could make the streets safer I considered how it could increase the freedom of movement and quality of life for people walking on them … aesthetic and practical solutions were treated as inseparable” (2005, 78). In a map and series of photographs, Tillett shows how, between 1995 and 1998, Tillett Lighting Design (also the lighting designer for the exhibition) collaborated with residents of a neighbourhood in Brooklyn, New York, to create a different character for its streets. Tillett targeted sites of civic importance or sites that posed a high risk for crime and implemented what she refers to as precise and low-cost measures (Fig. 2). Her firm installed Edwardian lamps, which traditionally hang lower and have a more luxurious, ornamental appearance than standard “anti-crime” lighting. In addition to using this older lighting style, which we associate with distinguished heritage neighbourhoods, Tillett made subtle changes to the illumination of an underpass and to the facades of community buildings such as the library and church. By simply altering the angle, intensity and colour of their illumination, these sites were transformed (Fig. 3). Tillett notes that the process of community engagement contributed to an enhanced quality of life as the places she altered have not been vandalized in eight years (85), a fact that is effectively illustrated with this display.

10 In the “Seasonal City” photographs of contemporary snow castles, ice sculptures and historic postcards and prints of Montreal in winter explore Montreal’s infamous capacity for “nordicity” and hivernité (its character of northernness and winterness as expressed by Pressman (2005)). The labour involved in removing the same snow and ice from clogged winter streets takes almost equal billing to the phenomenon of the “ice palace” or temporary architecture built out of snow and ice. “The biggest event of the carnival, the revellers’ mock storming of the palace, occasioned a flood of light. Torches in hand, thousands surrounded the castle, which was protected by fireworks and simulated explosions,” writes Latouche (2005, 116).

Fig. 2, 3 New York, Brooklyn 1995-1998. By Tillet Design for the New York City Department of Transportation. Photos Lynn Saville & Carrie Snyder. SENS_ 0376R.01.

Display large image of Figure 2

11 The feigned destruction of the castle kindles a desire to quit the cold and dark of winter, whose spirit is embodied in the icy yet ephemeral form of the palace. The fires—or fireworks—symbolize the return of heat, warmth and comfort. Zaha Hadid and Cai Guo-Qiang’s contribution to the 2004 “Snow Show,” Caress Zaha with Vodka/Icefire,3 refers to this traditional understanding of the spectacle of the ice palace. In that display Guo-Qiang poured vodka over Hadid’s curving architecture of ice and snow and set the sculpture on fire. The flames melted into the blocks, changing and ultimately destroying the sculpture, evoking the transitional nature of the seasons. More importantly, as Hadid notes, the flaming sculpture “[provoked] joy and a sense of exploration in its visitors” (2004, no pagination). That joy has historical continuity as the collection of historical prints and postcards suggests.

12 What is less clear is the relationship between labour, class, knowledge and release. In Montreal as elsewhere, the creation of the ice palaces was dependent upon masons’ knowledge and techniques while the palace forms emulated the kinds of buildings that average working people could never expect to inhabit. Much as Canada’s National Film Board’s 1956 documentary, Déneigement, points to a history of labour within the seasonal city, so too is that history hinted at with the popular ritual-istic “destruction” of the ice palace. While we are welcome to construct this genealogy ourselves, the exhibition proposes very little in the way of a deeper connection between the contemporary practice of building ice sculpture and the historical, vernacular aspects of ice palaces, the relationship and access of working-class citizens to the winter festivals and less still about the symbolic “destruction” of the architectural forms of the dominant classes.

13 Canadian acoustic ecologist and composer, R. Murray Schafer, figures frequently in the exhibition. Schafer suggests “noise is unwanted sound … noise is the wrong sound in the wrong place. This makes noise, to be sure, a relative term” (2005, 163). Accordingly, “Sound of the City” invites us to seat ourselves on its oversized, off-white ottomans and pick up one of the many gently swaying headsets (Fig. 4), which offer “one-minute vacations” or aural escapes to various locations around the world including New York, Paris, Calcutta, Dhaka and Fez.4 The visitor may also listen to differences in sounds recorded from a given Canadian city in the present and from the same city in the past. One of the most powerful of these is a recording of Vancouver from 1973 in which a First Nations man speaks in his native language, a reminder that such languages are part of a history of colonialism whose official policy, until very recently, has been assimilation. The Canadian recordings are of excellent quality and diversity. They come largely from the World Soundscape Project directed by Schafer at Simon Fraser University in the 1960s and 1970s. From the shouts of people in parks to the hum of buildings, these soundscapes offer a sense of the city that succinctly and powerfully expresses the differences between urban locations in a manner that dramatically retains spatiality as a condition of the gallery experience.

14 Spatiality is a quality that is comparatively absent in other rooms whose themes, likely for practical reasons, depend upon sight for their communication but whose densely visual expectations of the viewer seem somewhat at odds with the stated goal of the project. If the ensuing conclusion one could draw—that vision is limited in terms of understanding the city—was intentional, then the “Sound of the City” installation would be a success, if hard-won. But it is undeniably a great success in the sense that it draws from such a variety of locations, sounds and accompanying associations. These recordings provide an unexpectedly rich form of material culture, particularly in how they historicize and contextualize sound. Asking how and when certain sounds emerge (the internal combustion engine, for example) and disappear (the policeman’s whistle), the installation reminded me of the distinctive, rhythmic sound that English “steam engine” trains made before British Rail converted to diesel. I realized how the loss of this sound related directly to the decline of the English coal mining industry after the Second World War and its particularly harsh demise under Margaret Thatcher’s anti-union, Conservative government. My sisters and I used to sing a song to accompany that special, now-silent cadence of the steam engine which is evocative of our occasional childhood travels. This installation taught me to think with and beyond such nostalgic reminiscing to broader economic, social and political losses as signified by the absence of sound.

15 Where absence can be critically analyzed for the missing sound’s inscription in changing economic and social relations, presences can be critically reflected upon as well. For example, the curator’s passion for prosaic, ubiquitous, yet meaningful, city surfaces such as asphalt is considered with “Surface of the City.” Photographic documentation of the history of asphalt, pamphlets and publications dedicated to promoting and understanding asphalt and physical contact with actual, satisfyingly-large chunks of the material itself together create “Surface of the City.” The smell of asphalt pervades the room, not unpleasantly and I was immediately drawn to touch the inky black matter in its various forms. A basin of highly refined asphalt—smooth and just slightly more resistant to the touch than Plasticine—awaits visitors’ fingertips, the traces of which swiftly vanish in its satiny, inky surface. Large chunks of unrefined asphalt glitter in the spot lighting, beautiful and dark, as if Barcelona architect Antonio Gaudi and American modernist sculptor Tony Smith had collaborated to produce a work of art.

Fig: 4 View of the installation Sense of the City. Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montréal Photo Michel Legendre. 28_10_ 05_ML_014.

Display large image of Figure 3

16 The surprisingly aesthetic qualities of asphalt share the stage with a history of the material and its implication in urban renewal and sanitation movements. Overwhelmingly, however, the pleasure in this room lies in an engagement with this highly tactile substance. Kate Busch (Acting Head of Educational Services, CCA) advised me that during the first weeks of the exhibition, the asphalt samples were unfortunately damaged by visitors. Likely, patrons took too seriously the Richard Register quotation on the wall, “I love destroying asphalt and maybe you’d like to join the party.” Because of this overly enthusiastic treatment of the displays, visitors may now only touch the basin of asphalt. One wonders, however, whether a greater politicization of the material in question would have distracted those same visitors from their exertions. Asphalt is present in most petroleums and, as such, is embedded within crucial, current debates and conflicts including First Nations’ land disputes, the very controversial American occupation of Iraq and the emergence of Venezuela as a new socialist leader on the basis of its oil resources. The installation does an admirable job of informing visitors of the versatility, cost-effectiveness and centrality of this black matter beneath our feet to the modernization of cities worldwide. I believe that this impact could have been strengthened by acknowledgement of asphalt’s place within global struggles and politics.

17 Regarding the question of global impact, if not global politics, An Te Liu’s “Untitled (Complex II)” is a concise meditation upon the verisimilitude of modern architecture and its accoutrements. Composed of a series of small air conditioning units, the installation reads immediately as a scale model of a somewhat bleak modern city—treeless, white and isolated. The uncomfortably cool temperature of the room is explained as soon as the little “buildings” whir into action, expressing the ways in which post-Second World War architecture and industrial design slip aesthetically into one another’s territory (Fig. 5).

18 The theme of air conditioning is reiterated in a display of promotional catalogues from the collection of the Canadian Centre for Architecture. A Honeywell catalogue from 1946 deploys vivid post-World War 11 imagery of the avenging hero and the privileged site of both domesticity and democracy—the single-family home. A muscled, masked avenger hovers protectively over a bravely modern little dwelling, reminding visitors, obliquely perhaps, of the considerable marshalling of resources between 1842 and 1950 in the battle to purify urban and residential environments, both in the western world and its colonial outposts. As Liu’s work suggests, however, the consequences of the broad adoption of air conditioning have hardly been positive; the artificial cooling of entire buildings has created a series of hermetic environments that have the multiple detriment of being expensive, environmentally demanding, uncomfortable and a culprit in the increase of exterior temperatures.

Fig. 5 Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montréal. Photo Michel Legendre. 20_01_06_ML_020.

Display large image of Figure 4

19 The history of urban smell is the least explored in the installation despite its strong presence in the accompanying publication.5 The series of urban scents produced for the exhibition by the New York-based company Symrise and exhibited in crystal flasks are synthetic versions of familiar olfactory experiences: garbage, cut grass, rain, subway cleanser and a bakery. Whether or not these are completely convincing (“garbage” was undeniably pungent, while “grass” was quite lovely), they provide a necessary museological counterpart to the invoking of sound, sight and touch in the city. Indeed, it is in its most touchable, listenable, whiffable aspects that Sense of the City works as a meditation on the materially embodied experience of the city, if not its material culture. Yet, while experience and response are heavily privileged, there is little discussion of the ways in which our highly differentiated bodies do experience the city differently.

20 As a series of subjective encounters, the exhibition leaves unaddressed the ways in which individuals experience cities in the company of each other. Questions that lingered for me after leaving the exhibition were not so much prompted by their presence in the installations, but by their absence: how do embodied specificities such as gender, race, class and community affiliation affect the readings that we make? And how might the material and historical specificities of the objects on display be pressed to reveal more of their contingency as seen with Schafer’s work on sound? Even further, how might the mess, dirt, unpredictable vitality of cities be introduced into an exhibition in such a way that retains a sense of the city’s dependence, not just upon individual response, but upon individuals acting within a society together because, as Margaret Olin writes, “people existing in the same space are of consequence to one another. Our actions, therefore, can have consequence on them. Looking into their eyes, we take responsibility for what we do to them, or more to the point, what we leave undone” (1992, 97).

References

Borden, Iain and Jane Rendell, eds. 2002. The Unknown City: Contesting Architecture as Social Space. Cambridge and London: MIT Press.

Derrida, Jacques. 2003. And say the Animal Responded? In Zoontologies: The Question of the Animal. Ed. Cary Wolfe. Trans. David Willis. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Geismar, Haidy. 2004. The Materiality of Contemporary Art in Vanuatu. Journal of Material Culture 9(1): 43.

Graburn, Nelson H. H. and Aaron Glass. 2004. Introduction. Journal of Material Culture 9(2): 108.

Hadid, Zaha. 2004. The Snow Show. http://www.thesnow-show.

Haraway, Donna. 2003. The Companion Species Manifesto: Dogs, People and Significant Otherness. Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press.

Hayden, Dolores. 1995. The Power of Place: Urban Landscapes as Public History. Cambridge, MA and London: MIT Press.

Latouche, Pierre-Edouard. 2005. Quoted in Sense of the City: An Alternate Approach to Urbanism. Ed. Mirko Zardini. Montreal: Canadian Centre for Architecture and Lars Müller Publishers.

Leach, Neil, ed. 1997. Rethinking Architecture:A Reader in Cultural Theory. London: Routledge Press.

Olin, Margaret. 1992. Forms of Representation in Alois Riegl’s Theory of Art. Pennsylvania: Penn State University Press.

Pallasmaa, Juhani. 2005. Quoted in Sense of the City: An Alternate Approach to Urbanism. Ed. Mirko Zardini. Montreal: Canadian Centre for Architecture and Lars Müller Publishers.

Pressman. Norman. 2005. The Idea of Winterness: Embracing Ice and Snow. In Sense of the City: An Alternate Approach to Urbanism. Ed. Mirko Zardini, 129-38. Montreal: Canadian Centre for Architecture and Lars Müller Publishers.

Rose, Gillian. 2001. Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to the Interpretation of Visual Materials. London: Sage Publications.

Schafer, R. Murray. 2005. Quoted in Sense of the City: An Alternate Approach to Urbanism. Ed. Mirko Zardini. Montreal: Canadian Centre for Architecture and Lars Müller Publishers.

Tillett, Linnea. 2005. Quoted in Sense of the City: An Alternate Approach to Urbanism. Ed. Mirko Zardini. Montreal: Canadian Centre for Architecture and Lars Müller Publishers.

Watson, Sophie and Katherine Gibson, eds. 1995. Postmodern Cities and Spaces. Oxford, U.K. and Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

Williams, Raymond. 1989. Culture is Ordinary. In Resources of Hope: Culture, Democracy, Socialism, 3-18. London and New York: Verso.

Zardini, Mirko, ed. 2005. Sense of the City: An Alternate Approach to Urbanism. Montreal: Canadian Centre for Architecture and Lars Müller Publishers.

Notes