The Treimane Art Pottery

Gloria LesserConcordia University

Introduction

1 The Treimane Art Pottery was active for about forty years, from 1949 until the early 1990s, a considerable time for a small but prolific cottage craft enterprise. Excellent Treimane pots can still be found in the country homes of the original owners or among the possessions of their descendants. The pots are still highly-admired personal decorative art possessions that reflect the traditional Latvian forms of their creators. Remarkably, the undertaking escaped the serious attention of art and craft scholars throughout its lengthy life span. This suggests an isolation of this venture from the official organizations that advocate on behalf of the Quebec craft industry.

2 A central theme of the history of the 20th century appears to be the mass migration of peoples, generally from repressive regimes to liberal democracies. These widespread demographic changes took place in the midst of competing economic systems: democracy versus totalitarianism. Historian and author, Latvian-born Modris Eksteins (1999) writes about the Baltic nations against this background of world history. His discussion about the Latvian immigrant experience parallels the experiences of numerous emigrants to Canada. The Treimane potters, like other craftspersons who fled their homelands during and following World War II, operated within dominant cultures and sub-dominant linguistic groups, often at a distance from the official ideology and bureaucracy of craft organizations and the established corporate world. Nonetheless, these unsubsidized immigrant potters can be considered among the corps of Canadian/Quebec crafters, even though their works may be better analyzed and compared to craft production occurring elsewhere in Canada and Europe than to the work of other Quebec potters. This is because the artistic sensibilities and motivations of immigrant potters generally differ from the interests of local producers whose artistic understandings are reinforced by regional academic theories. Naturalized Canadians are reconciled to the fact that their products are different because they work from an orientation that reflects an outsider’s perspective.

3 The Treimane Pottery represents an interesting case for the study of Latvian pottery in Canada and particularly in Quebec. It provides a frame of reference for examining the role of crafts in recreational tourism and serves as a benchmark for understanding how a particular craft practice—Western ceramic art post World War II—fits within the broader issue of location in rural Canada. The range and distinction of the Treimane Studio within the cottage craft industry is explored in this study and an attempt is made to show how traditional practices give character to the lives of individuals by contributing to the creation of their material culture.

4 For the author, however, this monograph about the Treimane Pottery is an important opportunity to focus on the ethnicity of one particular studio active in Quebec throughout the latter part of the 20th century. Attention to ethnicity is a matter absent from the Canadian craft industry and within the Canadian craft bureaucracy. This omission means that not only does an all-encompassing analysis of Canadian craft not occur, but in the case of the Treimane Pottery that inattention could have contributed to the demise of the operation.

5 In the interest of placing Latvian clay production within its ethno-cultural context and for lack of a command of Latvian, a number of Latvian people were interviewed. As well, The Canadian Encyclopedia and the Dictionary of Art were consulted.

Immigrant Crafters

6 The founders of the Treimane Pottery came to Quebec as craftspersons in the post-World War II period. They operated outside the academic milieu, outside the two dominant linguistic groups—French and English—and at a distance from the official ideology and bureaucracy of Canadian and Quebec craft organizations that sponsored, promoted and advertised art. In the l950s, displaced persons—what Canada of the 1950s called refugees—lived on the margins of society and were expected by many to stay there. At best, displaced persons were defined by their difference and generally ignored by the local populace. It is perhaps safe to say that the cultural position, or identity, of the Latvian clay potters was Latvian culture and clay culture—that is they were identified as Latvian people and as clay people.

7 There is no one clear and simple way to define “identity.” It is not a closed issue locked into a cultural condition. During the 1950s and early 1960s distinctions between emigrating groups were, for the most part, considered unimportant. That notion changed somewhat as Canada moved toward its centennial year and the concept of multiculturalism was embraced. There was still a perception, however, that identity could be slotted into a category identified by the bureaucratic modernist structures of Canadian multiculturalism, a phenomenon in Canadian practice that has often been cited as a form of exclusion, locking immigrants into cultural categories and denying a definition of identity as a continuing process. A politically-charged term, multiculturalism has often been strategically used to bring difference into conformity by countries, like Canada, that are usually known to take pride in absorbing differences.

8 The concept of multiculturalism, widely promoted throughout the 1960s and 1970s eventually gave way to the 1980s “multi-ethnicity.” During this period, craft also became politicized around current issues of race, gender, sexual orientation and class. Nonetheless, in that the face of crafts was universal, craftworks from around the world were utilized to demonstrate the inclusiveness of nations in a common global order, a satisfying concept during the Cold War.

Immigrant as Entrepreneur

9 Political events in the homeland of immigrant groups and those of the host country are considered when determining a suitable enterprise or occupation for immigrants. Traumatizing experiences of atrocities and upheavals brought on by ideological political polemics make way for existentialist theories that displace Kantian romanticism. For example, the artist-immigrant may face struggles with assimilation due to conflicting understandings about art. Caught between the superstructure and the infrastructure of the host country, the post-World War II artist-immigrant (indistinguishable from an émigré who was a political exile) was a displaced person who imagined a life in another country (Canada) and who envisioned a market within the hegemonic culture. If, as French philosopher Henri Bergson1 postulated, an original life force is carried through successive generations, (one would expect it to be especially true in the craft atelier, where the transmission of tasks, knowledge and skills are transferred in a shared community of the extended family) the Latvian potters had reason to believe that through the Treimane Pottery a purposeful and rewarding life could be achieved in their adopted country.

10 It is not surprising that entrepreneurship was the choice of many western and eastern European craftspersons who immigrated to North America. It was the preference of creative and independent-thinking artisans whose utopian ideologies resisted “industrialization.” Many who came to Canada during the 1940s and 1950s arrived with theoretical academic knowledge and highly advanced technical expertise attained through rigorous beaux-arts studies in their countries of origin. It might be assumed that one rationale for immigration under the Canadian sponsorship quota system was that their skills were required and that the newcomers were perhaps at least as competent as local producers trained in Canada’s art schools. In addition, during this time there was a healthy local market for country clay domestic wares.

11 For any immigrant or immigrant group, cultures overlap: those of their country of origin and those of the host country. For those settling in Quebec, three or more cultures overlap—French, English and the culture of the immigrant. In mid-20th-century Quebec, the craft forms of Latvia, transferred through image, symbol, colour and design, were part of Quebec craft practice. Notwithstanding that social and linguistic differences isolated ethnic practitioners and conditioned their markets, the Latvian craft forms found resonance in a region of the province where the tourist and craft markets were being developed in the Laurentians. By tapping into a renewed interest in cultural ethnicity (including the old Eastern European folk traditions) the Treimane potters found a market for the clay wares common in their Latvian homeland.

12 Location, modes of production, iconography, sponsorship and ideologies are among the issues that confronted artisans wishing to practise their trade after emigrating. Practitioners new to a country typically conform to the customary organizational structures and behaviours. During the period in question pottery-making was romantically viewed as a holistic process and the countryside studio was considered a safe haven for craftspersons. Although a few western and eastern European immigrant artists were domiciled and active there, the Treimane Pottery was the only immigrant ceramics operation established during the 1950s in the Val-David region of the Laurentians, a district that became an enclave for artists and their creative expression.

Latvia/Canada Connection

13 While the time frame of this study is the mid-to-late 20th century, the Latvian Canadian connection predates the 20th century. The first Latvian-Canadians, mainly farmers, were 1890s refugees from Tsarist Russia who settled mostly in Manitoba and Alberta. Seeking work in Canada’s more populated provinces, some moved east during the Depression. The Canadian census of 1941 lists 975 Canadians of Latvian ancestry.2 A much larger number of Latvians left their homeland some forty years later, again to escape the horrors of an oppressive regime.

14 Latvia is a rural nation on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea. Neighbouring Russia, Latvia was occupied by Russia for much of the 20th century. It achieved independence from Russia in 1917 after the overthrow of the Romanov regime only to be again taken over by the Soviet Union in 1940. In 1941 Latvia was occupied by Nazi Germany until the Soviet Union regained control in 1944. Russians have lived in Latvia for generations, but the numbers rose sharply after the country was annexed by the Soviet Union. Only after glasnost under Mikhail Gorbachev did Latvia regain independence, but by the time the Berlin Wall fell, the Russian language was dominant and ethnic Latvians had been reduced to a thin majority in their own country.

15 In 1945, 110,000 Latvians fled to Western Europe where they were classified as displaced persons. Of these, 14,911 eventually immigrated to Canada. It was during this period that those who would eventually establish the Treimane Pottery arrived in Quebec.

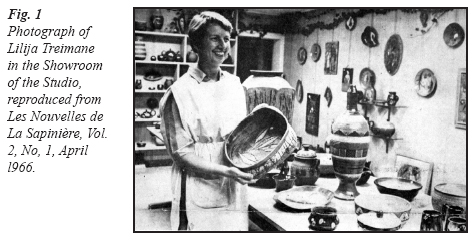

Latvian Artistic Cultural Legacy

16 According to Jeremy Howard, distinctive “golden age” Latvian culture dates from the first millennium BCE to the third century.3 The influence of Viking art is conspicuous from the end of the 9th century. Exclusive Baltic forms were developed that include dotted lines, like woven patterns, form rectangles, zigzags, small triangles, rhombs (parallelograms), circles and striations. These ornamental motifs were applied to virtually all metal surfaces. Archeological studies reveal that the Latvian decorative and household items of agrarian communities contained geometric fertility symbols of the sun and moon. Patterns inspired from designs in traditional decorative Iron Age architecture can be found on metal, leather, wood, textile crafts and later in ecclesiastic wares (the majority of Latvians are Lutheran).

17 The patterns are basic Latvian symbols found in textile designs of utilitarian woven, knitted and embroidered domestic cloths and carpets of natural wool and linen. Borders were composed of expansions of symbols used for traditional folk costumes and were included on items such as sashes or shirts, for example. Latvian fire crosses were endemic with more than forty-eight variations in existence. The designs of stars, rising suns, fire crosses and harvest gods—common to Celtic/ Baltic/Nordic mythology—are most commonly seen today in carved and painted Latvian leather and wood crafts with landscape or peasant figures; or wooden musical instruments with cut-out star motif and carved geometrical bands. Their stringed kokle of linden wood resembles a zither (sitar).

18 Traditional Latvian craft of the 20th century is actually a homogeneous production based on a variety of traditional colours achieved by Latvian specialists who develop dye for the textile trade. An art in its own right, this process has been passed from one generation to the next generation of individuals interested in dye as a craft form. For most ethnics, including Latvians, this informal training is augmented with studies in the art and craft academy of the country of origin. As explained by Rafina Mikelsons, a Latvian resident of Montreal who was interviewed by the author, the consistency of the Treimane colour palette in clay is probably the result of the range of hues achieved by natural dyeing for materials used in the textile field. The colours are made from natural materials and acids: grasses, local berries, fruits and vegetables; from a variety of woods including maple, birch, linden and aspen; or from scraped fungus or bark.

19 The use of folkloric and figurative motifs is characteristic of Latvian craft products as well as of European and Scandinavian craft wares. The figurative tradition is also a feature of non-immigrant North American modernist clay craft and is found in high-fired clay, earthenware clay or folk-clay categories. While the North American products might resemble their ethnic counterparts, people who know and understand ethnic production recognize the difference.

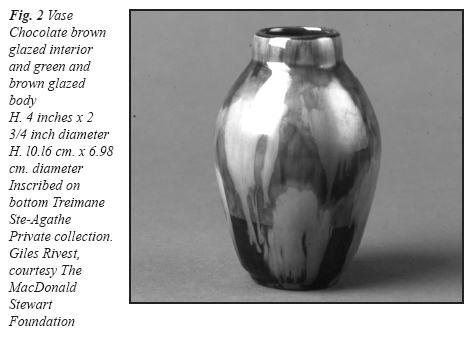

Fig. 1 Photograph of Lilija Treimane in the Showroom of the Studio, reproduced from Les Nouvelles de La Sapinière, Vol. 2, No, 1, April l966.Fig. 2 Vase Chocolate brown glazed interior and green and brown glazed body H. 4 inches x 2 3/4 inch diameter H. l0.l6 cm. x 6.98 cm. diameter Inscribed on bottom Treimane Ste-Agathe Private collection. Giles Rivest, courtesy The MacDonald Stewart FoundationZigfrids' Art Pottery in Ste-Agathedes-Monts, Quebec

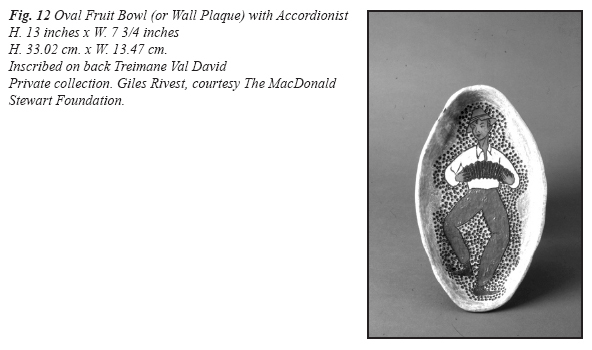

20 In the latter part of the 1940s, a Ste-Agathe potter known only by the surname of Elstermen was recruiting experienced potters for his small moulded-pottery factory, called Quebec Art Pottery (1947-1951). Lilja and Zigfrids Jursevskis were two of the people whose immigration to Canada was sponsored by Elstermen. By entering Canada as displaced persons the couple were freed from Wirzburg, the German detention camp where they were interred.

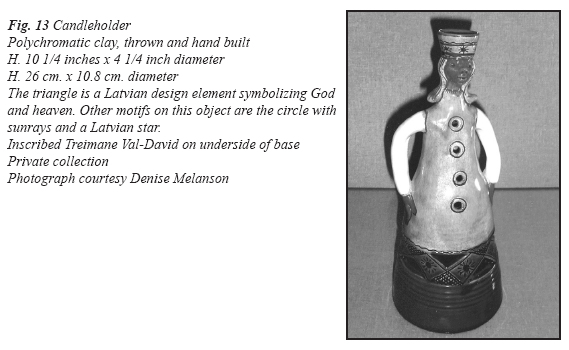

21 The Polish-born painter/sculptor, Zigfrids Jursevskis was a former graduate and one-time professor at the School of Applied Arts and Crafts in Riga, the capital of Latvia. He also held a degree from the Latvian Academy of Art.4 From 1936-1944 Zigfrids headed the ceramics department at the Museum of History and Art in Liepaja. Lilja (Murnieksj) Jursevskis, a talented painter and ceramist and one of her husband’s gifted students, also earned the equivalent of a Bachelor of Fine and Applied Arts (Fig. 1). After coming to Canada, Zigfrids Jursevskis stayed at Quebec Art Pottery in Ste-Agathe for the compulsory first year. Lilja, however, chose to stay with Elstermen long enough to bring her mother “out” to Canada.

22 With his departure from the Quebec Art Pottery, Zigfrids opened his own operation in Ste-Agathe. Zigfrids’ Art Pottery offered to the public stock dinner sets, decorative objects for the home and corporate objects such as ashtrays and coffee mugs. All products were adorned with traditional Latvian motifs. Zigfrids’ monogram, ZJ, was inscribed under the glaze. Zigfrids Jursevskis, however, was not strictly a studio potter but rather more a semi-abstract sculptor in the figurative tradition who worked in stone and bronze as well as clay. In 1957, when Lilja and Zigfrids legally ended their marriage, Zigfrids relocated to Toronto where he set up another studio located at 1425 Bloor Street West. This too, he named Zigfrids’ Art Pottery. Here he concentrated his efforts on teaching pottery and producing sculpture. He remarried yet another one of his students, who also happened to be Latvian.

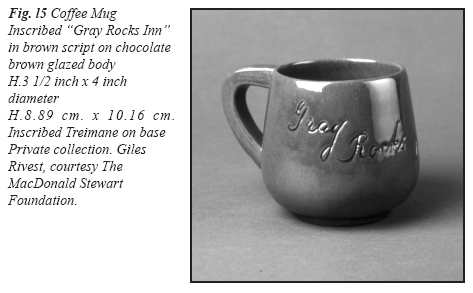

The Treimane Art Pottery

23 In 1957, Latvian-Canadian painter and potter, Lilja Murnieksj and John Jursevskis, one of her two sons, built their studio/home/showroom in Val-David, situated on the highway at 980 Route 117 North. (This old major local route has since been largely replaced by Laurentian Autoroute 15 North to Exit 76). John was trained as a potter by his parents, Lilja and Zigfrids. Lilja took her mother’s maiden name, Treimane, for the new studio. In the basement of the studio was a small gallery where the works of other artists were exhibited. This entrepreneurial woman also maintained an outlet in Ste-Agathe, the nearby summer and winter resort area. Following Lilja’s death in Quebec in 1991, John Jursevskis briefly carried on the business.

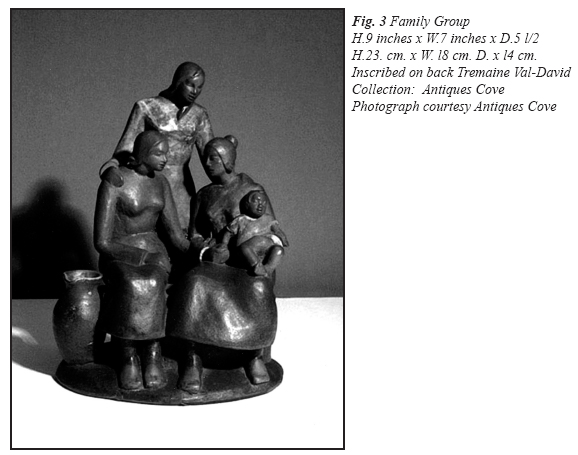

Fig. 3 Family Group H.9 inches x W.7 inches x D.5 l/2 H.23. cm. x W. l8 cm. D. x l4 cm. Inscribed on back Tremaine Val-David Collection: Antiques Cove Photograph courtesy Antiques Cove

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 4

24 Treimane Pottery initially produced vessels that were almost identical to those produced at Zigfrids’ Art Pottery with the conventional Latvian warm-colour palette of rust, yellow, brown, honey and greens (Fig. 2). The Treimane wares were distinguished by the typical Latvian pictograms used by Lilja’s former husband. Over time, however, Lilja added animated figurative images of her Latvian fellow countrymen that portrayed activities of everyday life. By doing this Lilja was able to focus further on the customs of her Latvian heritage.5 Cursive script with the signature, Treimane Ste-Agathe, Treimane Val-David or simply Treimane identify these undated clay products.

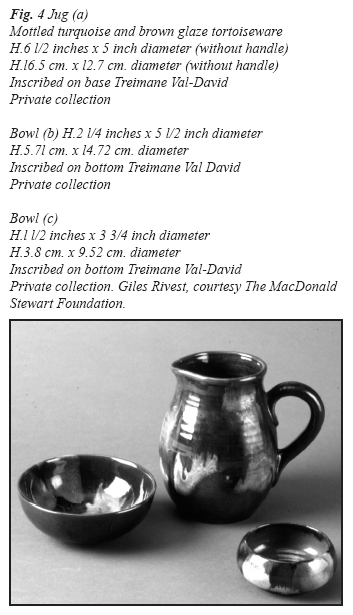

25 The Treimane product line consisted of kerosene or incense lamps, candleholders or lamp bases, vases, wine sets, goblets, mugs, casseroles, bowls of many varieties and sizes, dinner and breakfast sets, dinner bells, planters, wall-pockets for dried local wild flowers or weeds and tiles for table inserts or fireplace surrounds. Fine individual figurative and group sculptural works were also produced, but whether they were commissioned, produced as company specialties or promotional wares is not known at this time (Fig. 3). The most popular and least costly of the semi mass-produced wheel-thrown Treimane country crockery was “tortoise” tableware (Fig. 4). Lead-glazed, this splotchy reddish-brown ware was low-temperature fired at cone O 6.6 Oxidized copper glaze was used for turquoise and mottled green tortoise vessels.

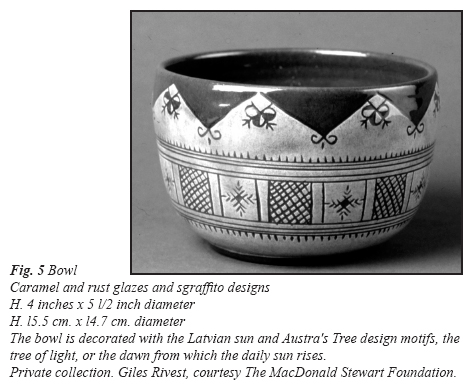

26 Another well-received line of decorative staples for home display was glazed shiny caramel, with white clay slip poured over the body to achieve the uniformity of an opaque glaze (Figs. 5, 6, 7). This ware was covered with sgraffito markings of Latvian geometric symbols of ancient fertility and was obviously oriented to naturalized Latvians or their family and friends in Latvia, who could decipher the cryptograms. For those outside the cultural context the works appeared to be merely charming geometrical repeat or all-over patterns.

Fig. 5 Bowl Caramel and rust glazes and sgraffito designs H. 4 inches x 5 l/2 inch diameter H. l5.5 cm. x l4.7 cm. diameter The bowl is decorated with the Latvian sun and Austra's Tree design motifs, the tree of light, or the dawn from which the daily sun rises. Private collection. Giles Rivest, courtesy The MacDonald Stewart Foundation.

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 6

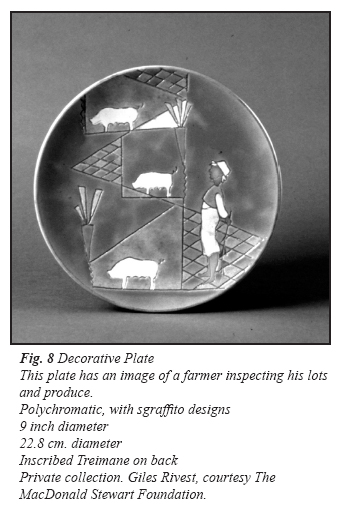

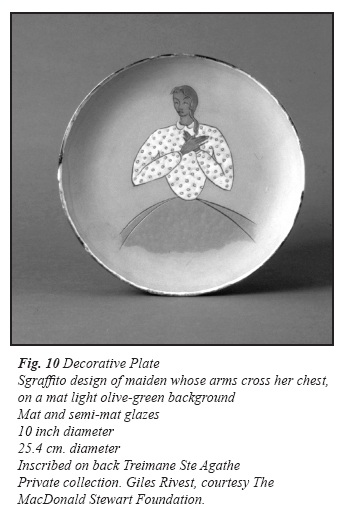

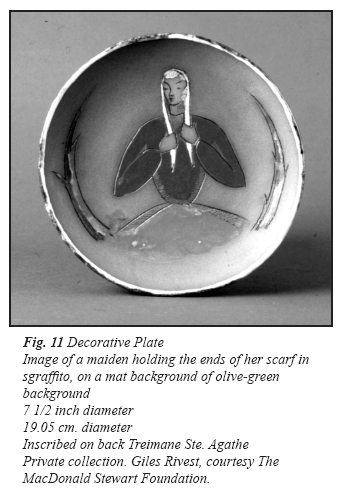

27 As noted above, much of the Treimane product line consisted of everyday items that served a utilitarian function—lamps, mugs, planters, for example. Another product category was decorative pieces designed as art to be mounted on the wall. In addition to satisfying an aesthetic sensibility, such goods further enabled the artisans to illustrate and prominently display aspects of their culture. A series of decorative plates, bowls and small dishes provided a surface for pastoral images that were left unglazed (Figs. 8, 9, 10, 11). In contrast, colourful glossy glazes were selected for the pieces that portrayed people in traditional costumes, such as youthful male singers in shirts and peasant hats playing concertinas; other characters might sport vests and breeches (Fig. 12). Such items were generally glazed on the backs of each piece with the Treimane shiny tortoise glazes meeting the surfaces at the front edge to form a border on the rim. According to contemporaries of Lilja and John Jursevskis, these particular wares were highly desired objects in Latvia where they were sometimes taken as gifts.

28 Whether utilitarian or decorative, some of the wares created by the Treimane potters were considered unique. One novel candleholder is kept in a private collection. The face, arms, hands and torso of the three-dimensional figurative candleholder were hand-modelled. A crown served as a headpiece; the base, in the form of a skirt, was wheel-thrown (Fig. 13). The prototype for the piece can be traced to a German late-16th-early-17th century Jungfrauenbecher—a type of wager cup whose design took the form of a girl with a widespreading skirt holding a bowl above her head. When inverted the skirt becomes the upper cup and the bowl the lower one.

29 Clients who understood the cultural value of the product purchased choice pieces. In recent years some fine works have surfaced at estate sales. For example, in April 2004 Antiques Cove of Montreal was responsible for liquidating the estate of Marcia Perlman. At this event some Treimane pieces were identified, among them an exceptional hand-modelled, figurative red clay conversational group (Fig. 3) and an attractive decorative plate with sgraffito design with a mother-and-child theme (Fig. 14).

Fig. 7 Vase Caramel and chocolate brown glazes and sgraffito designs H. 6 l/4 inches x 4 l/4 inch diameter H. l5.88 cm. x l0.8 cm. diameter The ubiquitous Austra's Tree Latvian symbol is one design element decorating this vase. Inscribed on base ZJ Ste-Agathe Private collection. Giles Rivest, courtesy The MacDonald Stewart Foundation.

Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 9

Display large image of Figure 10

Display large image of Figure 11

Display large image of Figure 12

Display large image of Figure 13

Display large image of Figure 14

Display large image of Figure 15

30 In the practise of their craft the Treimane potters were in tune with the demands of the market. Besides the pieces that specifically focused on their ethnicity, they also produced stock ware for commercial enterprises, such as hotels. The well-established Gray Rocks Inn in Mont Tremblant had its name, written in cursive script, inscribed on the belly of coffee mugs made for them by the Treimane potters (Fig. 15). Private pottery commissions were also common in the 1950s and 1960s, with individuals personalizing mugs or other clay items by having their family name etched into the clay.

31 The Treimane potters worked in a formalized tradition in which the essential features of motifs and pattern were reduced to conventional formulae or stylizations. As previously noted, colouration was in keeping with the Latvian practice of securing colours from nature. Their highest firing was Cone O 3. Wheel-thrown items were made of Nova Scotia clay. The human figurative images that appear on the Treimane pots vary in form, movement and activity, but in their unity and consistency they form a coherent, particular iconography which today, could fall under the term “ethnic stereotypes.”

Ethnicity and Canadian Ceramics

32 Like “identity” the term ethnicity defies a simple all-encompassing definition. The term brings to mind a variety of associations—the shared cultural characteristics of a people, religious or racial traits, customs and patterns of behaviour, are examples. Elliott Oring refers to the word as any “speech, thought or action based upon this sense of [ethnic] identity” (1986, 24). Flood defines ethnicity as being “distinguished by national or cultural characteristics, customs and language” (2001, 10-11). For purposes of this paper dealing with the material creations of a particular ethnic group, Wsevolod W. Isajiw’s definition is appropriate. Isajiw suggests ethnicity refers to:a group or category of persons who have common ancestral origin and the same cultural traits, who have a sense of peoplehood and Gemeinschaft type of relations, who are of immigrant background and have either minority or majority status within a larger society. (1974, 12)The Latvian immigrants who are the subject of this monograph were a minority within Canada and within the province of Quebec. It is understandable that in their new country they would find comfort in creating the material manifestations of their ethnicity. Stern tells us that through symbols of ethnicity, ethnics stand out in a multicultural world by defining their place and position as it relates to their ethnic past and present (1991, xii). One symbol of the ethnicity of the Latvian potters was the clay vessels they produced for sale. It is therefore unfortunate that within the Canadian context, ethnic crafts—of which ceramics is a subset—are seldom identified as ethnic. (Of the few survey texts that exist dealing with Canadian craft, cultural theorist Sandra Flood is exceptional in that she addresses craft within the context of Canadian culture.7)

33 The absence of a discussion about ethnicity in Canadian craft—Native or aboriginal craft, it must be said, has merited its own category—has led to a situation wherein early-20th-century Canadian anthropologists, social scientists and historians set the nationalist framework whereby ethnic craft became subsumed under Anglo-Canadian and Franco-Canadian craft. In Quebec particularly, this system was perpetuated by craft champions and fuelled by bureaucratic and nationalist interests, especially during the period known as the “Quiet Revolution.” The inclusion of immigrant craft production among Canada’s domestic offerings meant that the craftwork of newcomers to Canada was not privileged—that is not presented, acknowledged or judged—as the material culture of an outside ethnic group. Within that context, the uncertainty of a multicultural world (Stern 1991) can only be exacerbated when the cultural voices of ethnic artists are silenced through a lack of acknowledgement of their work. This pattern of silencing, extended through l930s socialism to Canada’s centenary, perhaps helps to explain why so little is known of, or written about, the Treimane Pottery enterprise.

Identity and Ethnicity Celebrated

34 The Latvian Centre situated in Lachine continues to be the centre of community life for Latvians in Quebec. Among other things, the Centre served as the central depot for Treimane ceramics. It also served as the structure through which week-long festivals were organized and taken every two or three years to community halls in Toronto and Michigan. On such occasions choirs performed; symphony concerts, recitals, folk dances and theatre performances were held; art and craft exhibitions were mounted and the Treimane wares were prominently featured.

35 At such gatherings it was notable that the images of dancers and singers on the walls of the vessels exactly mirrored the festivities that were taking place. In the decoration of the product line there was no attempt to depict the worldly events of modern society; instead the emphasis was to consciously and deliberately reflect the culture of their Latvian creators. While it often worked to their advantage, the choice of peasants in folk imagery on Treimane vessels was not specifically intended to capitalize on the ethnic trend or to find a clientele for folk clay per se. The imagery was simply a continuation of traditional Latvian clay production.

Conclusion

36 When they started their enterprise the wares of the Treimane Pottery primarily decorated the cottages and summer homes of Quebec’s more affluent classes. While outsiders to Quebec’s mainstream pottery culture as it emerged from the Quiet Revolution, the Treimane potters witnessed the changes in Val-David brought about by the development of Quebec’s Laurentian area as a tourist region. Because of their particular ethnic focus they were excluded from the process of development as the tourist became the focal point of clay wares or, for that matter, of any other product that could be cheaply produced and taken home for souvenirs. Clearly, the Treimane potters did not ignore the tourist market as a source of income—the strategic location of their studio is witness to this fact—but their focus was always to continue to create craft wares from their ethnic perspective. While not shunning the tourist, what distinguished the Treimane Pottery from local and indigenous production was that the Treimane product was not pretentiously geared to tourists, the export trade or to ceramics wholesalers. Rather, the objective of the Treimane practitioners from the outset was to sustain themselves economically as craftspersons, producing objects that reflected their artistic and cultural values.

37 The idea that immigrants carry an outsider’s detachment from institutionalized power structures in general may be especially true for the ethnic artist. In the case of the Treimane Pottery, the products were obviously craft items created by a small minority within the larger Canadian and Quebec hegemony. In operating outside of the official craft world, the Treimane potters chose not to underscore “otherness;” nor did they attempt to promote themselves as subjects in a colonized culture within the dominant culture. Rather, they saw themselves as Latvians in a host country living a life of purpose that embraced their ethnicity and traditional practices. That ethnicity was conveyed in the folk figurative images depicted on their vessels and made available to the general population. It was unfortunate that the wider public was not trained to distinguish between clay objects produced by local ethnic practitioners and the imports that flooded the North American market after World War II. The Treimane Pottery operation was further marginalized as a result of the Modernist tendency of the day to distinguish art as more socially relevant than a utilitarian craft product—such as clay wares. For these reasons alone, it is not surprising that the cultural value of certain craft practices became less significant, a step that one could say led to the creation and reinforcement of the craft ghetto.

38 The practice of categorizing all craft produced in Canada as “Canadian” is a flaw within the Canadian craft world that is compounded by design and craft historians who accentuate the high-design stylistics of global modernist factory aesthetics. While “fine craft” is distinguished by its quality, ethnic crafts are relegated to the background. Ethnic craft is either misunderstood, deemed retardataire or considered synonymous with folk art, which it is not. (The problem of mis-categorizing is also seen in Canada’s museums where the craft artifact is often explicitly of ethnic origins as opposed to being national or folk in character.)

39 Without the help of appreciative advocates (e.g., historians or material culturalists) the experiences of ethnic artists in the diaspora are largely left untold. Despite the desire to do so, ethnic artists are often reticent about telling their story, to speak for and to promote their work. Their products may rival the creative work of the host community, but without an official designation as “ethnic,” “invisible” artifacts become material culture without destiny, unable to find their own place in Canada’s public art or craft museums. Having no specific destination or official home, “ethnic pop” or what could be called “conceptual ethnic ceramics,” Treimane clay vessels survive as mementos languishing in transit between nebulous categories of “ethnic” or “modern” ceramics, in the popular art museum, the ceramics gallery of fine arts, the craft museum or the craft fair. For this reason it may be said that a lack of understanding on the part of the general public about the Treimane artists—including the origins of their work, what distinguished their wares from mass-produced pottery and that the patterns and motifs symbolized the values and customs of an immigrant group—contributed to the invisibility, if not certain oblivion, of the Treimane Pottery within Canada.

References

Eksteins, Modris. 1999. Walking Since Daybreak: A Story of Eastern Europe, World War II, and the Heart of our Century. Toronto: Key Porter Books.

Flood, Sandra. 200l. Canadian Craft and Museum Practice, I900-l950. Mercury Series Paper 74. Hull: Canadian Centre for Folk Culture Studies, Canadian Museum of Civilization.

Howard, Jeremy. l996. Latvia. In The Dictionary of Art, ed. Jane Turner, 846-53. UK: Macmillan Groves Publishers.

Isajiw, Wsevolod W. 1974. Definitions of Ethnicity. Ethnicity. 1(1): 111-24.

Oring, Elliott, ed. 1986. Folk Groups and Folklore Genres: An Introduction. Logan: Utah State University Press.

Stern, Stephen. 1991. Introduction. In Creative Ethnicity: Symbols and Strategies of Contemporary Ethnic Life, ed. Stephen Stern and John Allan Cicala, xi-xx. Logan: Utah State University Press.

Notes