The Aron Museum at Temple Emanu-El-Beth Sholom in Montreal

Loren LernerConcordia University

Résumé

Lorsque le musée Aron ouvrit ses portes en 1953, au temple Emanu-El-Beth Sholom à Montréal, il était le premier musée d’objets cérémoniels juifs au Canada. Durant ses premières années d’existence, le rabbin Stern, avec sa conception de la collection, les membres de la famille Aron en tant que bienfaiteurs et l’artiste Sam Borenstein, qui contribua à sélectionner les objets, jouèrent des rôles significatifs dans son développement. Cet article explore la description originelle du musée Aron afin de montrer la manière dont les valeurs humanistes et esthétiques attribuées aux pièces exposées suivaient le schéma des musées et expositions juives d’avant l’Holocauste. Pour des raisons variées, les interprétations religieuses, ethnographiques et historiques des objets cérémoniels du musée Aron était initialement minimisées dans l’exposition publique. Aujourd’hui, la provenance et les associations mémorielles de ces objets, aussi bien que l’explication des rituels juifs, expriment plus pleinement la signification multi-niveaux de l’art cérémoniel juif.Abstract

In 1953, when the Aron Museum at the Temple Emanu-El-Beth Sholom in Montreal opened it was the first museum of Jewish ceremonial objects in Canada. In its early years, Rabbi Stern—in his vision of the collection, the Aron family as benefactors and the artist Sam Borenstein who helped to select the pieces, played significant roles in the development of the museum. This article explores the original description of the Aron Museum to show how the humanistic and aesthetic values attributed to the items followed the pattern of pre-Holocaust Jewish museums and exhibitions. For a variety of reasons the religious, ethnographic and historical interpretations of the ceremonial objects of the Aron Museum were initially minimized in its public display. Today, the provenance and memory associations of these objects as well as an explanation of Jewish rituals more fully express the multi-layered meaning of Jewish ceremonial art.1 In Europe and the United States, Jewish museums have been a visible part of Jewish life since the late 19th century. These museums often originated with collections of Jewish ritual objects that were owned by wealthy Jews and donated to synagogues, seminaries and Jewish educational institutions.1 In Canada, the collecting of Judaic artifacts began much later, in 1953, when the Aron Museum opened at Temple Emanu-El in Montreal, now called the Temple Emanu-El-Beth Sholom.

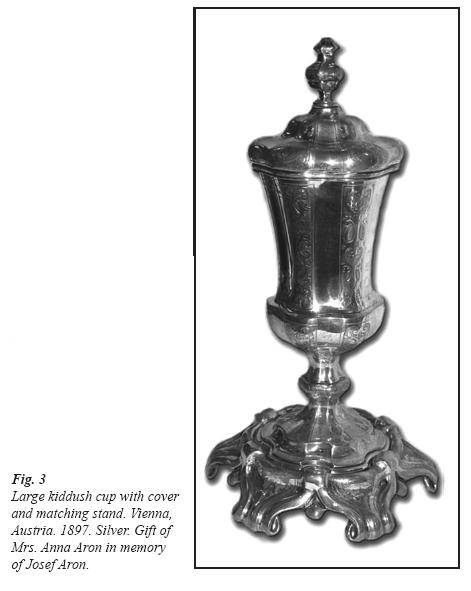

2 The inauguration of the Aron Museum took place on September 4, 1953. A photograph (Fig. 1) bearing the caption “This is the first time that a Museum of Religious Art Objects has ever been established in Canada” shows a single display cabinet containing five objects (Temple Emanu-El Weekly Bulletin, 1953). Standing next to the cabinet are the donors, Mr. and Mrs. Josef Aron and Rabbi Dr. Harry Joshua Stern. On the top shelf is a kiddush cup of Austro-Hungarian origin, dated 1858), and two early 20th-century pidyon haben trays from Poland. On the bottom shelf is a Chanukah menorah crafted in the late 19th century by the silversmith Hans Boller of Frankfurt for the House of Rothschild (Fig. 2). Next to the menorah is a pewter Passover Seder tray from 1770. In the centre of the tray is a design of an urn holding flowers—on its rim, the maker identifies himself in Hebrew: “I am the writer Leib bar Zalman from Mansfort in the year 5530, twenty-fifth day in the month of Nissan, according to the abbreviated way of counting the year.” With the exception of the tray, these ritual objects were crafted in Europe between the 18th and early-20th centuries, mainly by Christian silversmiths.2 They were commissioned by Jewish individuals or community representatives to be used in religious ceremonies both in synagogues and homes.

3 Josef Aron was a German Jew who immigrated to Canada from Frankfurt in 1904. As the story is told, Rabbi Stern3 was so impressed with Aron’s Chanukah menorah, which Aron had received as a gift from his brother Paul, he asked if he could borrow it for the Temple’s Chanukah festival (Stern 1961). He subsequently convinced Aron to donate the menorah, along with four other objects in his collection, to the synagogue, thus creating a museum. During the next seven years the museum acquired more than forty Judaic objects.4 They came from three main sources: the Judaica collection that Josef’s brother Paul had accumulated in Germany before the Second World War; items Josef and other Temple members purchased from Sam Borenstein, an artist and antiques dealer whose wife Judith was Josef’s niece and Paul’s daughter; and the Jewish Cultural Reconstruction commission, whose mandate following World War II was to find homes for Jewish ceremonial objects that had been stolen by the Nazis and dispersed throughout Europe.

Fig. 1 Inauguration of Aron Museum, September 4, 1953. Display cabinet with donors: Mr. and Mrs. Josef Aron and Rabbi Dr. Harry Joshua Stern.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 3

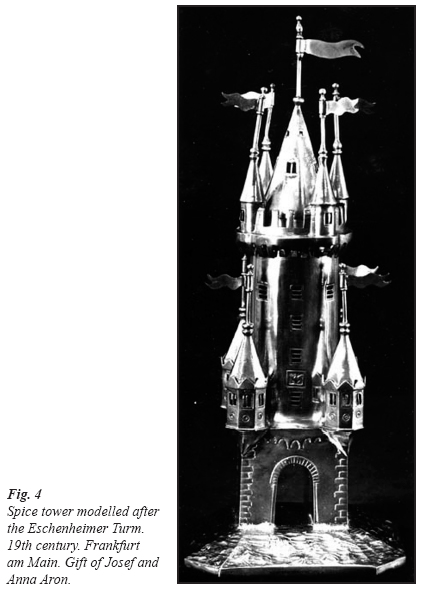

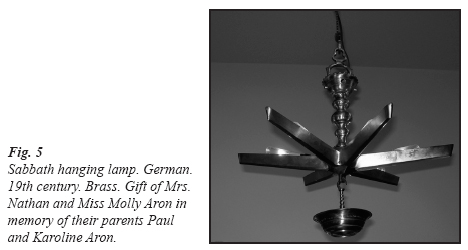

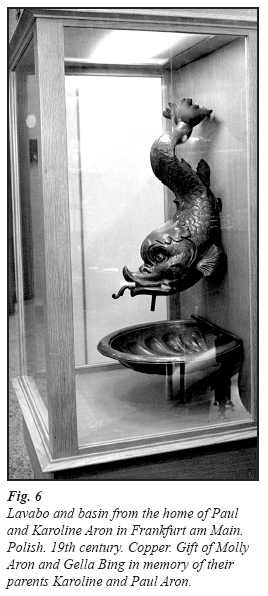

4 In recalling her childhood home, Judith remembered that her father, a Frankfurt businessman and Jewish scholar, had a substantial collection of Judaica as well as a large library of Hebrew books. The objects in the collection were displayed in glass wall cabinets in the living room.5 While they made a handsome display, they were also used by the family for the Sabbath and religious holidays. There were candlesticks that were lit to welcome the Sabbath, kiddush cups for each child for the blessing over wine at the Sabbath meal (Fig. 3) and spice boxes for the Havdalah prayers that marked the end of the Sabbath and the beginning of the work week (Fig. 4). There was also an etrog for holding the special fruit used in blessings during Sukkot, the annual harvest festival, and a Passover plate, which held the assortment of foods referred to in the pre-dinner Seder readings recalling the Exodus from Egypt. In the family dining room was the Shabbat lamp which was lit every Friday night before sunset (Fig. 5) and a special washbasin called a lavabo (Fig. 6). The lavabo was filled with water by the children in preparation for Shabbat and was used by the family to ritually wash their hands before her father recited the blessing over the bread.

5 Judith immigrated to Montreal in the mid 1930s with her sister Gella, and in 1938 she married Borenstein. In the meantime, Hitler had come to power in Germany and decreed that Jews leaving Germany could not take their possessions with them. Realizing that his collection of Judaica was at risk, Paul devised a plan to save it. He entrusted a long-time employee, a non-Jew named Baum, with the task of taking one precious object at a time to the home of a friend who lived in Zurich, Switzerland. Over the next several years Baum made many such trips. When Paul was forced to leave Frankfurt, he retrieved the objects and took them with him to Palestine. Over the years he gifted some of them to his family in Montreal and they in turn donated them to the Aron Museum.

6 With an interest in collecting even more objects to donate, Josef turned again to Borenstein, who made many visits to Jacoby’s auction house on his behalf. Jacoby’s was well known for its brisk trade in European antiques. Although Josef died June 2, 1956, he secured the future of the museum by stipulating in his will “a Memorial Fund in the name of Josef and Anna Aron, the income of which is to be used for the purchase of Jewish Ceremonial Art objects and display cases, for the Museum in the said Temple founded by myself and my said beloved wife.”6 The Memorial Fund fell under the care of the museum committee, which was headed by Josef’s wife Anna. The committee continued to look to Borenstein for recommendations and to solicit donations by Temple members.

Fig. 4 Spice tower modelled after the Eschenheimer Turm. 19th century. Frankfurt am Main. Gift of Josef and Anna Aron.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 6

7 In 1960, Anna Aron wrote a short article about the museum in a commemorative monograph entitled The Emanu-El Story, 1882-1960 (n.p.). In it she explained that the “Jewish art objects” were “reminders of a Jewish past, as evidenced in the religious symbols of our people.” She also outlined the two objectives of the museum: “for our members and children of the Jewish faith to view the beauties of Jewish life through the ages,” and to explain Judaism to “persons of the non-Jewish faith, who come through the portals of Temple Emanu-El, that they too may learn the aesthetic side of our people, that these symbols dramatize the great ideals in Jewish life and teach the meaning of our great heritage and tradition.” As a permanent exhibition of Jewish ritual objects, the museum was both an affirmation of Judaism and a means by which Christians could become familiar with Jewish culture, religion and history and thereby learn about Judaism.

Jewish Emancipation and the Science of Judaism

8 Correcting misconceptions about Jewish beliefs and practices by explaining Judaism to non-Jews was considered an important defence against anti-Semitism. This defence grew out of a way of thinking that had developed almost two hundred years earlier in France, with the gradual emancipation of the Jews (Mendes-Flohr and Reinharz 1980,101-102). Following the French Revolution, Jews were granted citizenship and the full equality of each individual before the law. As Napoleon’s conquering armies marched east to Germany, Poland and Russia, citizenship in these countries was also granted, but this did little to alter the negative attitudes with which most non-Jews regarded their Jewish fellow citizens.

9 After Napoleon’s defeat in 1814, a mounting wave of anti-Semitism in Germany led to the “Hep! Hep!” anti-Jewish riots of 1819. In resistance, Jewish university students joined together to establish a sort of anti-defamation movement (Mendes-Flohr and Reinharz 1980, 182-83). They called themselves Verein fuer Cultur und Wissenschaft der Juden and were responsible for creating the “Science of Judaism,” a new historiography that through an objective methodology would correct misinformation about Jews and thus stop non-Jews from making slanderous accusations and taking anti-Semitic positions.

10 The principal aims of the Verein were to defend the right of Jews to participate fully in culture and politics and to expedite Jewry’s integration and assimilation into European society. Although the Verein dissolved in 1825, these objectives endured as central concerns of modern Jewish scholarship. It was believed that by approaching the Science of Judaism as an academic discipline based on the textual study of Jewish literature, Jewish learning would be released from theology and religious practice. In this way, intellectuals sought to depict Judaism from a historical and philosophical point of view. By striving to show how the Jew was like the rest of humanity, the strangeness of Jews and Judaism in relation to the larger world would disappear.

11 At the Temple Emanu-El in Montreal, Rabbi Stern shared these ideas. His ideological motives for reaching out to the non-Jewish community were premised on the belief that ignorance and misinformation were the primary sources of discrimination. He believed that prejudice would disappear if factual information were clearly communicated. In 1927, before coming to the Temple Emanu-El from Uniontown, Pennsylvania, Stern had already started on his ecumenical campaign with the production of a short publication entitled Jew and Christian (1927). From the time of his arrival in Montreal until his death in 1984, interpreting Judaism to the Christian world and speaking publicly against injustices were an important part of his rabbinical activities.

12 In keeping with Rabbi Stern’s ideas, it was decided that the religious use of the objects at the Aron Museum would not be a dominant feature in their presentation. Rather, ritual practices would be described in normative terms with an emphasis on finding commonalities within the larger categories of Western culture and universal beliefs. This was clearly delineated in Anna Aron’s description of the collection in The Emanu-El Story, 1882-1960: “The various Ceremonial Art Objects are used in the functions of daily living. Their functioning encompasses all the senses, including hearing, since the intonation of blessings is a necessary accompaniment to the ceremonies” (Anna Aron 1960, n.p.).

13 What mattered most to Rabbi Stern and the Museum Committee was the cultural designation of the “Ceremonial Art Objects” as authentic artistic works in relation to their wider historical and philosophical significance in Western civilization. As described by Anna Aron (1960) the “precious silver seven-branched candelabra” was a reminder of the Temple in Jerusalem where the menorah played an important role. The lavabo was “handmade copper,” more than a hundred and fifty years old. The basin had a symbolic relation to the “act of purification which was required of everyone who entered the Sanctuary in Jerusalem.” The “rare Shabbat Lamp with a dove of peace carved thereon” was expressive of a “religion in which light and the act of lighting play a dominant role.” The items were primarily characterized according to Biblical history, the techniques used in their crafting, the materials they were made of and the motifs that decorated them. How they were used in ceremonies and what they symbolized in terms of Judaism was given less attention.

14 This type of analysis was not only based on he scholarly traditions established by the Verein, it was consistent with a long tradition of displaying Judaic objects in public exhibitions (Kirshenblatt-Gimblett 1998, 79-80). In Paris in 1878, in the first public display of Judaica at the Exposition Universelle at the Palais Trocadéro, Jewish ceremonial objects were carefully described as works of art. According to those who mounted the display, if Judaism was to be considered part of the history of the Western world, Jewish ceremonial objects needed to be classified in a hierarchy that included art works created by civilized people everywhere.

15 The display consisted of eighty-two objects that belonged to Isaac Strauss, an Alsatian Jew who arrived in Paris in 1827. A musician and chef d’orchestre to Napoleon III, Strauss purchased the objects during his extensive travels throughout Europe, especially Germany. When the collection, now somewhat larger, was exhibited nine years later at the Anglo-Jewish Historical Exhibition in London, the presentation again stressed the artistic sensibility of the objects rather than their ritual significance (Kirshenblatt-Gimblett 1998, 85-86).

16 In the 1890s, art historians and scholars throughout Europe were increasingly interested in the research and display of Jewish ritual objects (Grossman with Ahlborn 1997, 11-14). In 1895, the Society for the Collection and Conservation of Jewish Art and Historic Monuments was established in Vienna. Thirteen years later, Heinrich Frauberger, a Catholic art historian and director of Duesseldorf’s Museum of Applied Arts, curated the first exhibition of Jewish ceremonial objects in Germany and founded the Society for Research of Jewish Art Monuments in Frankfurt.

17 Frauberger was the first trained art historian and museologist to have an interest in Jewish art. He amassed a private collection of Judaica that was purchased at about the time of the Duesseldorf exhibition by Salli Kirschstein, a Berlin businessman who displayed the objects in a private museum in his home. The reason Kirschstein gave for showing the collection sounds very much like the rationale behind the Aron Museum. “A museum must concentrate [on making the past] come alive and serve as a source of contemplation and knowledge. A Jewish Museum can be of great value in keeping our people together. It can also considerably influence the attitude of non-Jews towards Jews and Judaism, because the meagre knowledge of Jewish life is and has been one of the strongest motives for anti-Jewish attitudes” (Gutmann 1991, 176).

18 Regardless of these efforts, anti-Semitism was on the rise in Germany and in 1925 Kirschstein sold his collection to the Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati (it is now housed at the Skirball Museum in Los Angeles). Other collections did not fair so well. The Vienna Jewish Museum, founded in the late 1890s, was destroyed by the Nazis during the Second World War. Other museums were also plundered, including the Jewish Museum in Berlin, that was bequeathed by the Dresden collector Albert Wolf after World War I, and the Frankfurt Jewish Museum, established in 1922.

The Loss and Recovery of Judaica

19 More than thirty years passed before some of the lost treasures were retrieved by the Jewish community. In 1956, the bulletin of the Canadian Jewish Congress announced: “Congress has been made the trustee of a number of ceremonial objects, recovered in Germany after the last war and which in many instances are the only remnants of the once flourishing Jewish communities in Europe. Congress made available some of these objects to the newly built congregations in Canada as a permanent link between these congregations and the Jewish communities in Europe which were destroyed.”7 This entry explains how, in 1956, the Aron Museum came to acquire ceremonial objects through the Jewish Cultural Reconstruction, a supranational commission administered in Canada by Congress.

20 In The Rape of Europa (1995), Lynn Nicholas chronicles the plundering of art across Europe and the difficult restitution process. She explains that one of the problems at the conclusion of the Second World War was deciding what to do with “heirless” Jewish property. The traditional solution of reverting unclaimed cultural property to the state for distribution to museums and libraries was unthinkable when the nation in question had attempted to exile or kill the entire Jewish population of Europe. In late 1946, the American military asked Captain Seymour Pomrenze, a former employee of the National Archives in Washington, to go through the million or so Jewish books and objects that were sitting in Nazi depositories. He selected over a thousand Torah scrolls, prayer shawls, paintings, furnishings and ritual objects made of precious metals and stones for distribution to synagogues and museums worldwide by the Jewish Cultural Reconstruction. Many of the less valuable items were ultimately sold.

21 Countless stories exist of the loss and recovery of Jewish artifacts. Soon after the war, Mordechai Narkiss, director of the Bezalel Museum in Israel, travelled through Europe and retrieved thousands of Jewish art objects (Narkiss 1985). Closer to home, Montrealer Yehuda Elberg, a Holocaust survivor and private collector of Jewish ritual objects, discovered the kiddush cup given to him by his grandfather as a wedding present in 1939 at a New York auction house.8 In a work of fiction based on fact entitled The Iron Tracks (1998), Holocaust survivor Aharon Appelfeld evoked the endless search for remnants of the Jewish culture that had flourished in central European towns and villages for hundreds of years before the war.9

22 Since the 16th century, Jews had lived in large numbers in the vast region that stretched from modern Lithuania through Poland, Russia and Ukraine. In this “pale of settlement,” Jewish inhabitants developed an extensive shtetl village culture whose landmarks were synagogues, study centres and rabbinical courts. In Appelfeld’s story, the narrator is a kind of travelling salesman named Erwin Siegelbaum who rides the rails that were used to transport Jews to labour and death camps. Tracing the vanished outposts of Jewish life, Erwin buys abandoned Judaica for a song and resells it to collectors he meets along his route. On his journey through emptiness, the objects, including candlesticks, kiddush cups and sacred books, begin to affect him, ultimately tying him to the shadows of the lost Jewish world.

23 Montreal painter Sam Borenstein, who looked for Jewish ritual objects on behalf of Josef Aron and the Aron Museum, was one of those shtetl Jews. He was born in Kalvarija, Lithuania, and at the age of four moved to Suwalki, Poland, where his father, a rabbinical scholar, had found a job with the Singer Sewing Machine Company (Kuhnes and Rosshandler 1978). By 1908, the Suwalki census counted 13,002 Jews (Berelson 1989). Borenstein’s life in Poland came to an end in 1921 when, at age thirteen, he immigrated to Canada with his father and a sister. The end of Jewish life in Suwalki came later, on Saturday, October 21, 1939, when a Polish official arrived at the synagogue and demanded that Chief Rabbi David Lifshitz and two representatives of the community accompany him to the German authorities (Berelson 1989, 49-51).10

Fig. 7 Rabbi David Lifshitz and another man in front of a cabinet full of Torah scrolls smuggled out of Suwalki, Poland and brought to Kalvarija, Lithuania in 1940. Washington: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Chaya Lifshitz Waxman, acc. no. 35460.

Display large image of Figure 7

24 A photograph taken in a synagogue in Kalvarija shows Chief Rabbi Lifshitz and another man posing beside a menorah, several sacred books and a cabinet of Torah scrolls, some without covers, that had been smuggled out of Suwalki (Fig. 7). These items had been hidden by the Jews of Suwalki before their evacuation to the death camps. When it was discovered that the Germans had begun to find the objects and were selling the scrolls to shoemakers for their leather, a campaign was launched by some Suwalki Jews who had escaped to Lithuania to pay non-Jews to retrieve the remaining scrolls and take them to safety in Lithuania. However, with the German invasion of that country, both the Suwalki and Lithuanian Jews were rounded up and transported to death camps. The menorah, sacred books and scrolls of Suwalki were never seen again.

25 Borenstein’s search for Judaica took place in the context of a worldwide Jewish community deeply affected by the Holocaust and by the destruction of Europe’s once rich Jewish culture. However, even as the history of the objects and how they arrived in Montreal were uppermost in the minds of Borenstein and the members of the Temple, they chose to present and describe the objects in a manner consistent with the public exhibition of Jewish objects before the Second World War. In other words, their particular historic significance was overlooked in favour of an uplifting presentation of their spiritual and aesthetic values.

26 At Jacoby’s auction house, Borenstein regularly found Jewish ceremonial objects that had been acquired by dealers in Europe. Jacoby’s was also a clearinghouse for precious possessions sold by impoverished refugees and Holocaust survivors who had made their way to Montreal. In effect, as an immigrant from pre-war Europe, Borenstein was finding items that belonged to his own past. His most noteworthy discovery, which linked him to his childhood in Poland, were the two silver pidyon haben trays made in Poland that were part of Aron’s original donation to the museum.

Ethnography and Identifying Jewish Culture

27 Most of the objects in the Aron Museum collection are remnants of the once vibrant Jewish communities of Europe. As such, they represent the destruction of European Jewry and fall within the central aim of early 20th-century ethnography, which was to document and collect materials belonging to so-called disappearing peoples (Gruber 1959; Nurse 1997). The role of ethnography was to preserve the remains of a dying or dead society in the hopes they would reveal insights and values that would benefit modern-day society. In the early years, ethnographers did not imagine that genocide would be one of the ways a people would come to its end.

28 In fact, European Jewish scholars were studying shtetl Jews even before the Holocaust. The culture of these Jews, which had been held together by shared ritual and inter-community ties, was being rapidly transformed due to secular influences, modernization and the emigration of Jews to cities in Europe and America. In 1912, a Russian Jewish populist and playwright who went by the name of Semyon Akimovich Ansky organized the first Jewish ethnographic expedition into the towns and villages of Volhynia and Podolia, two areas in the Ukraine (Kampf 1984, 17-18). Members of the expedition, which included a photographer, a musicologist and students from the Jewish Academy of the University of St. Petersburg, distributed a questionnaire among the Jews that contained over 2,000 queries about Jewish life. They also took photographs, retrieved folk legends and songs and collected hundreds of objects and manuscripts. Although the expedition ended because of the First World War, Ansky continued his work as a member of the Red Cross. He visited destroyed villages on the fronts of east central Europe and salvaged what he could from synagogues and Jewish homes plundered by the Czar’s cassocks. In 1916, he opened the Jewish Ethnographic Museum in St. Petersburg, but it was briefly shut down by the Bolsheviks in 1918. The museum eventually closed in the 1930s, and today Ansky’s collection is located in the Russian Museum of Ethnography.

29 By representing Jewish folklore authoritatively, Ansky and other Jewish scholars also sought to counteract the offensive racial portrayal of Jews that was emerging around the world in so-called scientific academic texts. Their aim was to show the commonalities that existed between the traditional folkways of Jews and other Europeans. This interest in Jewish ethnography did not make headway in North America primarily due to the beliefs of Franz Boas (1858-1942), an assimilated Jew who was born and educated in Germany (Glick 1982, 546) and was later the founder of anthropology in North America. Boas’s dismissal of the ethnographic study of the Jew stemmed from his beliefs that Jews were not a race, that in any event there was no such thing as a “pure” race and that Jews did not have a unique culture and history. In some respects, Boas’s views stemmed from the Science of Judaism, whose objective was to integrate Judaism into the whole of human knowledge, and by so doing identify it as just another aspect of mainstream society.

30 Boas arrived in the United States in 1884 and was the first person to occupy the anthropology chair at Columbia University, where he introduced a science-based approach to anthropology (Lesser 1968). This involved studying a unique culture in all its aspects, including art, language, history and religion. Boas had done this kind of ethnological work among the Kwakiutl Indians of British Columbia and had also worked on the Bella Coola Indians collection at the Museum fur Volkerkunde in Berlin. He also exerted a strong influence on the theory and practice of anthropology in Canada. Edward Sapir, who worked as an ethnologist at the new Division of Anthropology of the Geological Survey of Canada, was recommended and trained by Boas. The principal aim of this division was to examine the culture and languages of the native races of Canada, gather and preserve all records and set up an educational display in the ethnological hall of the museum.

31 From Boas’s perspective, both Native Indians and French Canadians qualified as a culture with a specific history as a result of distinctive historical, social and geographic conditions. In 1913, at a meeting of the American Anthropological Association in New York City, Boas proposed to Sapir’s assistant, an ethnologist by the name of Marius Barbeau, that he embark on a study of French Canadian culture (Nowry 1995, 141-42). The suggestion arose from a comment Barbeau had made regarding the presence of French Canadian folklore in the legends of the Lorette Huron Indians. To encourage the inclusion of this new element in Barbeau’s research focus, Boas—in his role as editor of the Journal of American Folklore—wrote to the director of the Geological Survey of Canada, Reginald Walter Brock, suggesting that Barbeau become “an associate of the Journal, particularly for French-Canadian folklore.”11 He had to convince Brock to broaden the parameters of ethnological research in Canada beyond the exclusive study of the “native races.” In this way Boas expanded the mandate of the division to include the study of the traditional culture of French Canada.

32 At the same time Ansky was amassing evidence of Jewish life in the Ukrainian countryside, Barbeau was travelling to isolated communities in rural Quebec to gather songs, legends, artifacts and other physical evidence of his French Canadian roots. By 1925, a minor project had expanded into a comprehensive, lifelong investigation that examined architecture, woodcarving, textiles, pottery, silver and shipbuilding. The nature and scope of the Jewish Ethnographic Expedition in the Ukraine and Barbeau’s work in rural Quebec were similar from the point of view of ethnography. This similarity, however, was not recognized by Boas, who never wavered in his belief that Jewish culture was not unique.

33 In 1945, three years after Boas’s death, Raphael Patai wrote an article in the Journal of American Folklore that lamented the rejection of Jewish folklore and ethnology as an accepted field of study in North America. Why, he asked again in 1960, has Jewish folklore “not figured so prominently in American folklore research,” nor been “so integral a part of American folklore as the study of the folklore of other nationalities in this country” (Patai 1960, 12). A major reason was that Boas, while valorizing the distinctive traits of the Native, African-American and French Canadian peoples, denied the existence of a Jewish cultural or ethnic identity. According to Boas, the exclusion of modern Semitic folklore was justified on the grounds that much of their folklore was borrowed from other peoples and was therefore not unique. Patai argued that “this is true of the folklore of practically every people even those who have lived until recently in relative isolation” (13). Boas encouraged the study of the folklore brought to Canada by European settlers and the influence of European folklore on the American Indian, but would not agree that Jewish culture could participate in these kinds of exchanges.

34 For Boas, Judaism was strictly a matter of adherence to an ancient religion irreconcilable with individual freedom and humanism, which emphasized common human needs. “My parents had broken through the shackles of dogma,” Boas explained. “My father had retained an emotional affection for the ceremonial of his parental home without allowing it to influence his intellectual freedom” (Boas 1938, 201; Glick 1982, 555). Boas was committed to a humanism and freedom that repudiated Judaism along with other formal religious doctrines.

35 Under the guidance of Rabbi Stern, the central idea behind the Aron Museum was to show that these humanistic ideals were in fact compatible with Jewish beliefs. Although nearly all the objects had been salvaged from the synagogues and homes of destroyed Jewish communities in Europe, this was not how the museum was presented to Temple congregants and Christian visitors. In describing some of the “choice ornaments” in the museum, there was only one cursory mention of the Holocaust: “varied types of Hanukkah Lamps; some salvaged from the holocaust of the burning synagogues in Germany” (Aron 1960, n.p.). It had been decided that rather than convey the tragic story of historical circumstance, the museum would act as living proof of the positive universal qualities of humankind. The last sentence in the description of the objects states: “They reflect impressively the Jewish idea of life, namely its sanctity.”

36 Although Borenstein contributed to the collection and respected the museum’s interpretation of its collection, belonging to a synagogue and observing Jewish ceremonies and customs was incompatible with his personal and social beliefs. He recognized that his background could only be described in terms of a Jewish socio-historic reality, but the authority of religious practice held no meaning for him. Similarly, while Boas’s professional career was focused on documenting cultural traditions, from a personal and social perspective he considered identifying with a cultural group a relic of the past, incompatible with panhuman values. One of his central convictions, which arose from a “fundamental ethical point of view,” was that the “in-group” had to expand to include all of humanity (Boas 1938, 203; Glick 1982, 555). Nonetheless, Boas acknowledged that he could not abandon his European roots and heritage. “My ideals had developed because I am what I am and have lived where I have lived” (Boas 1938, 204; Glick 1982, 555). For both Boas and Borenstein, Judaism was a source of dogmatism and religious taboos and, as such, was the adversary of a modernity in which religious and ethnic distinctions were minimized.

37 Borenstein’s paintings and his sympathy with the presentation of the ritual objects at the Aron Museum were motivated by a belief in universal parallels. In his landscapes he merged the particulars of the eastern European shtetl and the traditional Laurentian village with the cosmology of a perfect world (Fig. 8). The expressive qualities of these paintings evoke a composite paradigm, wherein the memory of an ideal past is preserved in the humanistic values of the present. This is also true of the descriptions given to the Jewish objects at the Aron Museum, which minimize the impact of the Holocaust and stress universal and enduring truths.

38 As can be seen through Borenstein, Boas and Rabbi Stern and his congregants, the interpretation of the Judaica at the Aron Museum was a unifying force for Jews of different persuasions despite the troubling origins of the objects and the varying viewpoints about how they could be defined. After the Holocaust, many Jews believed that it was of the utmost importance to communicate that the essence of a culture could be preserved despite its terrible losses, and that this essence could be an operative concept in determining the creative forces of modern living.

Conclusion

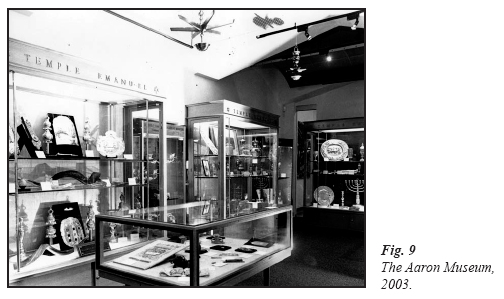

39 Today, there are various collections of Jewish ritual objects in Canada and new ways of describing these ceremonial objects. On September 23, 2000, the Royal Ontario Museum inaugurated its first permanent collection of European Judaica, consisting of more than sixty traditional objects that celebrate Jewish life and history. Like the collection at the Aron Museum, this collection is also a gift; the benefactors are Dr. Fred Weinberg and Joy Cherry Weinberg of Toronto. The objects are arranged according to life-cycle events and Jewish holidays and include descriptive panels explaining the purpose of each object. This emphasis on the specifics of the Jewish religion corresponds to how the objects of the Aron Museum, now numbering 230 (Fig. 9), were described in 1996 in a website created by Percy Johnson titled Hidden Treasures, Judaic Art in Context (http://collections.ic.gc. ca/art_context).

Fig. 8 Sam Borenstein. Sainte-Lucie, Winter. 1964. Oil on panel. 91 x 122 cm. Private collection.

Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 9

40 The presentation of Judaic objects has changed significantly since the Aron Museum’s inauguration in 1953. These objects are now being displayed with explanatory texts that provide a more in-depth analysis of Jewish rituals and customs. For example, the history of the objects that was overlooked in the early descriptions of the Aron Museum collection is now considered an important part of the object’s significance. At the Montreal Holocaust Memorial Museum a new permanent exhibition opened in 2003 that includes Judaic objects once belonging to Montreal Holocaust survivors. The objects are interpreted as an integral part of Holocaust history, with each one being imbued with recollections of life before, during and after the Holocaust. It was important for the donors that the museum accept these objects with the intention of telling their personal stories of loss and memory.

41 Judaic ceremonial objects are now being given multiple historical and symbolic meanings. This extensive inquiry was apparent in 1990 in the touring exhibition A Coat of Many Colours: Two Centuries of Jewish Life organized by the Canadian Museum of Civilization/Musée canadien des civilisations and curated by Sandra Weizman with accompanying publications by Weizman (1990) and Irving Abella (1990). The Canadian Jewish Virtual Museum and Archives (http://www.cjva. org) follows a similar pattern. This website was initiated in 2002 by Montreal’s Congregation Shaar Hashomayim and partners Temple Emanu-El-Beth Sholom, the Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue, United Talmud Torahs of Montreal, Centre communautaire juif, Communauté sépharade du Québec and the Holocaust Literature Research Institute of the University of Western Ontario. Here, Judaic artifacts are included among the many photographs, records and archival materials that define the personal and community history of the Canadian Jewish experience. The topics are diverse, including anti-Semitism, the Holocaust, religion, education, immigration, philanthropy and voluntarism, as well as entertainment, sports, the military and politics.

42 This expansive paradigm has also influenced more recent interpretations of the Aron Museum’s collection, which had originally been presented in keeping with Rabbi Stern’s ideas surrounding anti-Semitism, the Holocaust, the Science of Judaism and Jewish ethnography. In those days, deciding what not to say about the objects was as important as deciding what to say, and from there flowed the decision to use the objects to demonstrate the humanistic values of Judaism in the modern era.

43 Today, these same objects, like in other Jewish museums, are explored differently. In Andrea Korda's (2004) Keeping the Faith: Judaica from the Aron Museum (http://www.virtualmuseum. cajewishmuseum.org), created for the Community Memories website of Virtual Museums Canada, the objects narrate the story of the person or family who donated them to the Temple. The personal significance of each one is also explained. Starting with the Aron family, the website explores the artifacts given by donors to the museum from 1953 until now and, as such, shows how diverse objects carry unique family memories that coalesce to create one community. For the first time, the religious, historical, social and cultural contexts of these objects have been given full expression.

References

Abella, Irving. 1990. A Coat of Many Colours: Two Centuries of Jewish Life in Canada. Toronto: Lester and Orpen Dennys Publishers.

Anon. 1953. Temple Emanu-El Weekly Bulletin 27 no.1 (4 September).

Appelfeld, Aharon. 1998. The Iron Tracks. Trans. Yaacov Jeffrey Green. New York: Schocken Books.

Aron, Anna. 1960. The Josef Aron Museum of Jewish Ceremonial Art Objects. In The Emanu-El Story, 1882-1960: Over Three Quarters of a Century of Dedicated Service. Dedication volume commemorating the building of the new Temple Emanu-El, April 1960, Nison 5720.

Barbeau, Marius. 1936. Quebec Where Ancient France Lingers. Toronto: MacMillan.

———. 1941. Backgrounds in North American Folk Arts. Queen’s Quarterly 48 (Spring): 284-94.

———. 1946. Painters of Quebec. Toronto: Ryerson Press.

Berelson, Yeheskel. 1989. The Holocaust: The Destruction of Suwalk. In Jewish Community Book: Suwalk and Vicinity, 49-51. Tel Avi: The Yair-Abraham Stern-Publishing House.

Boas, Franz. 1938. An Anthropologist’s Credo. The Nation 147(6): 201-04.

Borenstein, Joyce. 1991. The Colours of my Father: A Portrait of Sam Borenstein. Animated film production. Montreal: Imageries and National Film Board of Canada.

Borenstein, Sam. 1968. [Unpublished memoir]. Borenstein family archives.

Glick, Leonard B. 1982. Types Distinct from Our Own: Franz Boas on Jewish Identity and Assimilation. American Anthropologist 84:545-65.

Grossman, Grace Cohen with Richard Eighme Ahlborn. 1997. The Science of Jewish Art and Culture. In Judaica at the Smithsonian: Cultural Politics as Cultural Model, 4-16. Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology no. 52. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Gruber, Jacob W. 1959. Ethnographic Salvage and the Shaping of Anthropology. American Anthropologist 61:379-89. Expanded version, 1968. http://www.aaanet.org/gad/history/033gruber.pdf.

Gutmann, Joseph. 1970. Beauty in Holiness: Studies in Jewish Customs and Ceremonial Art. New York: Ktav Publishing House.

Gutmann, Joseph. 1991. The Kirschtein Museum of Berlin. Jewish Art 16/17:176-77.

Johnson, Percy. 1996. Hidden Treasures: Art in Context (The Judaica Artifacts Collection of the Temple Emanu-El Beth Sholom). Schoolnet, Industry Canada. http://collections.ic.gc.ca/art_context.

Kampf, Avram. 1984. Jewish Experience in the Art of the Twentieth Century. Massachusetts: Bergin and Garvey Publishers.

Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, Barbara. 1998. Exhibiting Jews. In Destination Culture: Tourism, Museums, and Heritage, 79-128. Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Korda, Andrea. 2004. Keeping the Faith: Judaica from the Aron Museum. Community Memories. Virtual Museums Canada. http://www.jewishmuseum.org.

Kuhns, William and Léo Rosshandler. 1978. Sam Borenstein. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart.

Lesser, Alexander. 1968. Franz Boas. In International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, vol. 2:99-108. New York: Crowell Collier and MacMillan.

Mendes-Flohr, Paul R. and Jehuda Reinharz. 1980. The Process of Political Emancipation in Western Europe, 1789-1871. In The Jew in the Modern World: A Documentary History, ed. Paul R. Mendes-Flohr and Jehuda Reinharz, 101-102. New York: Oxford University Press.

———. 1980. The Science of Judaism. In The Jew in the Modern World: A Documentary History, ed. Paul R. Mendes-Flohr and Jehuda Reinharz, 182-85. New York: Oxford University Press, 182-85.

Narkiss, Bezalel. 1985. Judaica and Ethnography. Ariel no. 60:78-86.

Nicholas, Lynn H. 1995. The Rape of Europa: The Fate of Europe’s Treasures in the Third Reich and the Second World War. New York: Vintage Books.

Nowry, Laurence. 1995. Marius Barbeau: Man of Mana: A Biography. Toronto: NC Press.

Nurse, Andrew. 1997. Tradition and Modernity: The Cultural Work of Marius Barbeau. PhD diss., Queen’s University.

Patai, Raphael. 1945. Problems and Tasks of Jewish Folklore and Ethnology. Journal of American Folklore 59 (January-March): 25-39.

———. 1960. Jewish Folklore and Jewish Tradition. In Studies in Biblical and Jewish Folklore, ed. Raphael Patai, Francis Lee Utley and Dov Noy. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Stern, Harry Joshua. 1927. Jew and Christian: A Collection of Addresses. Uniontown, PN: The News Standard.

———. 1961. Entrusted with Spiritual Leadership: A Collection of Addresses. New York: Bloch Publishing.

Weizman, Sandra Morton, 1990. Artifacts from “A Coat of Many Colours: Two Centuries of Jewish Life in Canada”/Ob-jets de l’exposition “La tunique aux couleurs multiples: deux siècles de présence juive au Canada.” Hull, QC: Canadian Museum of Civilization/Musée canadien des civilisations.

Notes