Articles

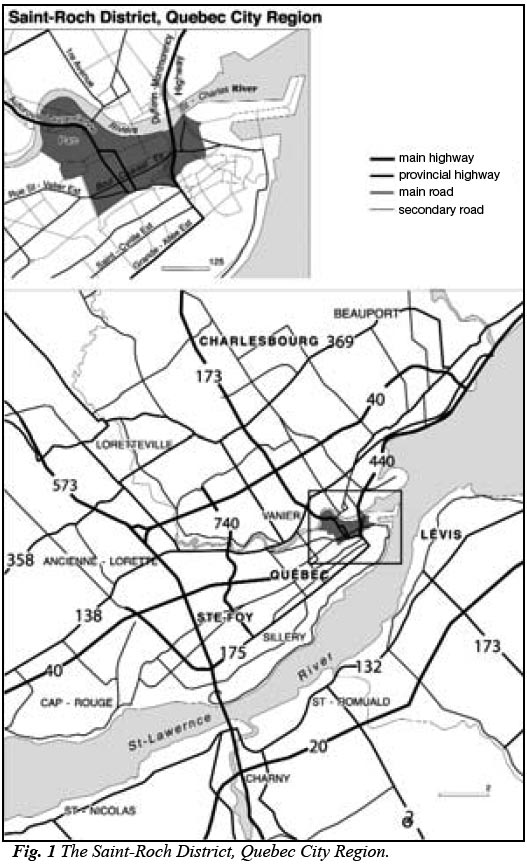

The "Totem Poles" of Saint-Roch:

Graffiti, Material Culture and the Re-Appropriation of a Popular Landscape1

Abstract

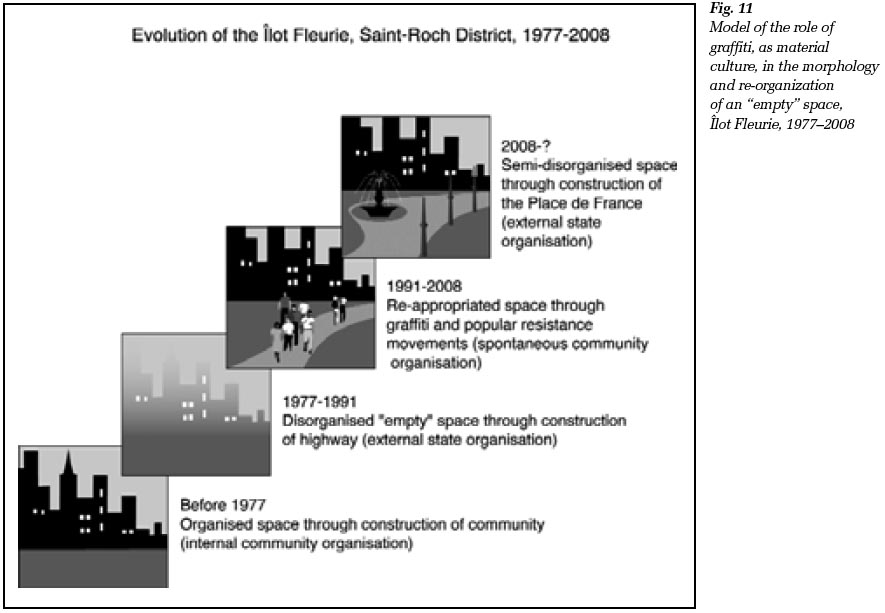

In 1972–73 the Dufferin–Montmorency highway was thrust through the working-class neighbourhood of the Parish of Notre-Dame in the Saint-Roch district of Quebec City, expropriating the homes of nearly two thousand people and raising an entire parish. Traffic flow improved, but the rows of support columns for the suspended highway, as the parish priest of Notre-Dame remarked, passed directly over the heads of the poor, replacing the paroisse with a new religious icon: the "cement totem pole." In time, this poignant metaphor, retold through the graffiti of local artists working beneath the overpasses of the highway, invested an anti-establishment iconographic power in the concrete highway supports. Recently, however, the "totem poles" of Saint-Roch have become the object of attention of Quebec as the city prepares for its four-hundredth birthday. While Quebec acts to promote renewal and national festivities in 2008, its use of state-aided subventions to replace graffiti with aesthetically-pleasing street murals in Saint-Roch threatens, as in the 1970s, to disorganise the area, this time through the gentrification and eradication of the "totem poles" of Saint-Roch.

Résumé

En 1972-1973, l’autoroute Dufferin-Montmorency s’est imposée au voisinage de la paroisse ouvrière Notre-Dame dans le quartier Saint-Roch de Québec, causant l’expropriation d’environ deux mille personnes et la suppression d’une paroisse complète. La fluidité de la circulation s’est améliorée mais, aux dires du curé de la paroisse Notre-Dame, les rangées de piliers soutenant l’autoroute suspendue s’élevaient directement au-dessus de la tête des pauvres, remplaçant la paroisse par une nouvelle icône : les « mâts totémiques en béton ». À l’époque, cette métaphore dramatique, évoquée par les graffitis des artistes locaux travaillant sous les viaducs, conférait aux piliers une puissance ico no graphique contre le pouvoir établi. Ces derniers temps, toutefois, les « mâts totémiques » de Saint-Roch retiennent l’attention de Québec qui se prépareà célébrer ses 400 ans. Alors que la ville prend des mesures pour promouvoir son renouveau et ses festivités nationales en 2008, l’utilisation qu’elle fait des subventions de l’État, en remplaçant les graffitis par des murales à l’esthétique engageante dans le quartier Saint-Roch, menace de bouleverser le secteur, comme en 1970, mais cette fois par l’em bour geoisement du quartier et l’éradication des « mâts totémiques » de Saint-Roch.

Icons of a New Religion

1 The day of 22 April 1972 was a significant one for many residents of the Parish of Notre-Dame-de-Saint-Roch, a working class district in the basse-ville (lower city) of Quebec City (Figs. 1 and 2). With no forewarning or ceremony, some 2 000 parishioners received registered letters announcing the expropriation of their homes for the construction of an autoroute. The highway overpass would go through their neighbourhood, connecting the provincial parliament in the haute-ville (upper city) with île d’Orléans and Côte-de-Beaupré, where many of the city’s bureaucrats and professionals were building news homes in the suburbs. The majority of the parishioners of Notre-Dame were small-businessmen and wage labourers, many dependent on government aid. In response to the expropriation of the area, the parish priest, the abbé Paul-Henri Lepage, commented that "the elevated highway was built on the heads of the poor. The Parish of Notre-Dame has disappeared, and in its place have been erected the icons of the new religion of modernity: the cement totem pole."3

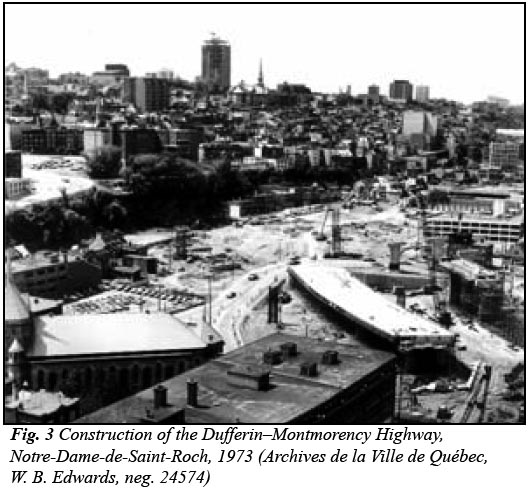

2 In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the Saint-Roch district was dominated by ship works, sawmills, mer cantile enterprises and living quarters and in the early twentieth century by tanneries, shoe and textile (corset) factories, breweries, department stores, and well-developed neighbourhoods.4 Following the Second World War, however, de-industrialisation and urban out-migration commenced. Then, in the 1970s, Saint-Roch had nearly one-tenth of its organized space, nearly an entire parish, unceremoniously amputated from its body politic with the construction of the Dufferin– Montmorency Highway. Many of the homes in the area, witnesses to the long history of the working classes of the city, were demolished to make way for a vast empty field of cement pylons anchoring the highway — the "liberated terrain" was transformed into a "lunar landscape"5 (Fig. 3).

3 Clearly, this highway project was part of the post-Second World War expansion in the use of the automobile and the consequent urban migration from the city to the suburbs, a phenomenon occurring across North America. Yet, the expropriation of the Parish of Notre-Dame for the construction of a highway was not only part of the privileging of post-Second World War automobile and suburban culture, it was also an element of what has been called "la loi d’altitude," or the "law of altitude," in Quebec City. By the 1930s, the haute-ville had for nearly three centuries been a religious, government, military, and intellectual capital where Quebec’s bourgeois had long been concentrated. The whole upper city was a sort of outdoor museum, an area of bourgeois respectability where tourists came to see the churches, gardens and government buildings. Basse-ville, on the other hand, was the district of the working poor, where water towers dominated the skyline, tourists never set foot, and nothing was written in English. Like many of the city’s sewage systems draining from the Upper City into the streets of the Lower City, the unceremonious expropriation of the Parish of Notre-Dame to facilitate traffic flow to the provincial parliament was part of the bourgeois domination of Quebec City politics.6

4 The perception of Quebec City by most Cana di ans is that of an old French city, the capital of Quebec, a UNESCO World Heritage site. While some 700 000 people call the city home, it is the Château Frontenac, the Citadel, the Grande Allée and the Montmorency Falls that domi nate official images of the city. Rare are the visitors who, as Raoul Blanchard noted in the 1930s, find their way into the working quarters of the city. The city must uphold an image of "respectability" that leaves little space for the "average" citizen to express him or herself publicly, especially if that articulation should run counter to mainstream discourse.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 35 One has only to think back to the anti-conscription riots and the use of troops to fire on citizens in the Saint-Roch district during the First World War, the mobilization of army units during the FLQ crisis in the early 1970s, or the construction of a security perimeter around the entire Old City during the Summit of the Americas in 2001. They are all reminders of how precarious freedom of expression has been in recent Quebec City history.7 As one resident, Jean Richard, recently exclaimed about Quebec’s new "zero tolerance" graffiti regulation, "It reminds me of the beginning of the 1970s, when the tourist season approached. The police would get out their boots and nightsticks to harass the youth who dared to meet in public places, just to hang out. The rule was you must keep moving: it was forbidden to stop on the sidewalk when you were in a group — two or more."8

6 One architectural historian has commented that, in North America, "it is rare that one associates a highway to a positive aspect of urban life…In Quebec, however, this paradoxical relationship [has flourished]."9 This study goes on to argue that it is the lack of truly free public space, coupled with a high level of police surveillance of government and tourist space in the city, that differentiates the graffiti beneath the Dufferin–Montmorency Highway from other similar spaces in American and Canadian cities. In constructing a "spatial void" of several blocks in length underneath the over-passes of the Dufferin–Montmorency Highway, the city created an unregulated space of "permissiveness" relatively free of surveillance.

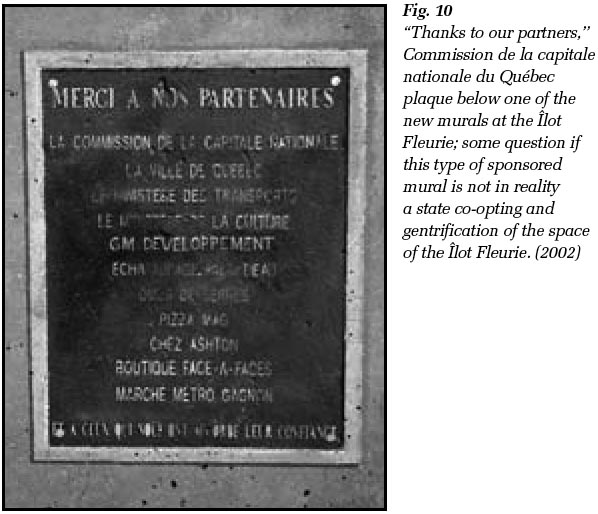

7 This space was quickly re-appropriated by the youth and dispossessed of Saint-Roch. They reconstituted it as a point de rendez-vous for legal and non-legal activities, including the writing and painting of expressive graffiti on the cement supports of the highway. As late as 1985, this activity was limited to a few socio-economic messages: "Me révolter contre les profiteur [sic] c’est : me libérer moi-même" ("By revolting against profiteers I liberate myself").10 Increasingly, however, the spaces beneath the overpasses have become a magnet for graffiti messages and murals of a highly visceral and expressive nature. Typically throughout urban North America, abandoned areas experiencing overt socio-economic mutation often prove favourable to experimental art because of the vacant space they offer and the availability of cheap rentals (housing, and studios) in the immediate area.11 In addition, the seclusion provided by the over-passes allows for freedom from surveillance and so accommodates freedom of expression:

8 Such texts constitute acts of resistance and expressive commentary on the hegemonic social processes beyond the control of the people. As such, they need to be decoded and, consequently, have attracted the attention of scholars. Graffiti "is a lively expression of feelings, points of view," writes anthropologist Denyse Bilodeau, a noted québécoise authority on the subject. Others have argued, "it gives voice to common people."13 Indeed, as a form of contemporary material culture, graffiti is viewed and remarked upon more so than most art in traditional museums and is difficult to ignore in the lives of most urban dwellers who pass by some form of graffiti each day. As sociologist Jeff Ferrell argues in his Crimes of Style, "Graffiti marks and illuminates contemporary urban culture, decorating the daily life of the city with varieties of colour, meaning, and style," providing "understanding of…specific social and cultural contexts in which particular forms of graffiti evolve." He continues, it is frequently used by otherwise voiceless actors in society to develop a public discourse of the "circumstances of injustice and inequality…the domination of social and cultural life by consortia of privileged opportunists…the aggressive disenfranchisement of…poor folks…and, finally, the careful and continuous centralization of political and economic authority."14

9 This is the case of Saint-Roch. It is the story of the unceremonious state expropriation of a working-class neighbourhood, and the "paving over" of an urban community. But it did not end there as it has done in so many other North American cities. In Saint-Roch, the very symbols of the state-sponsored "voiding" and "disorganization" of the Parish of Notre-Dame were the rows of highway supports passing through the district. Ironically, in time they were to become "symbols of freedom of expression" as local graffiti artists began using them as massive canvases upon which to paint images and messages dominated by a discourse of the socioeconomic plight of the poor and underprivileged of Quebec City. From signifiers of state power and bourgeois domination, in the words of the abbé Paul-Henri Lepage, the "totem poles" of Saint-Roch became transformed into internationally-recognized iconography of local material culture and freedom of expression through the act of writing and painting on them. It is this morphology which cries out to be studied.

Public and Popular Monuments in Quebec City

10 To have some understanding of the raison d’être of the anonymous graffiti painting beneath the Dufferin-Montmorency Highway, it is necessary to contrast that activity with the erection of public murals, monuments and statues that have come to dominate the public space of Quebec City since the Second World War. As a result of its long history as the political, military and cultural capital of French Canada, the contemporary paysage of Quebec City has been politically cultivated as a lieu de mémoire, a landscape of monuments that today is dedicated to the concept of the Berceau de l’Amérique française, or the "Cradle of French civilization in America."15 In 1998, the Commission de la capitale nationale du Québec (CCNQ) completed a census of the city’s public monuments inside the walled city. They tal lied some sixty-six monuments, twenty-four statues, and 329 plaques dedicated to the "collective memory of the québécois people."16 Since then, the com mis sion has erected a significant number of new monuments in ultimate preparation for the 400th anniversary of the city in 2008.17 For the average citizen of Quebec, however, the problem is: what is commemorated, and how? The objects of public commemoration in Quebec City, as in the nationalistic period of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, continue to be "patriotic" in their orientation to the politico-religious builders of the nation-state and have little to do with the daily concerns of the average "post-national" citizen of contemporary Quebec.18

Display large image of Figure 4

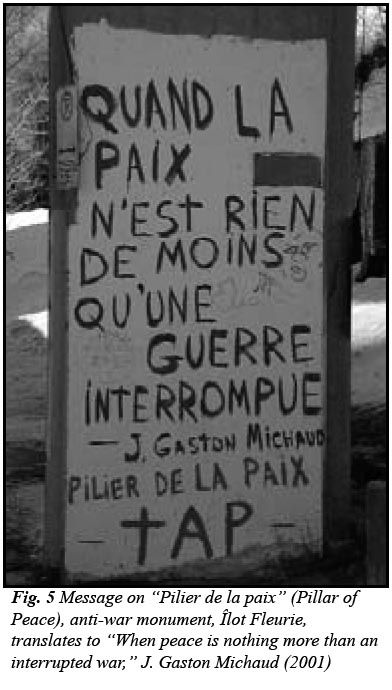

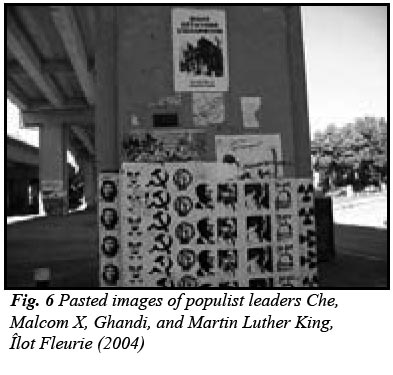

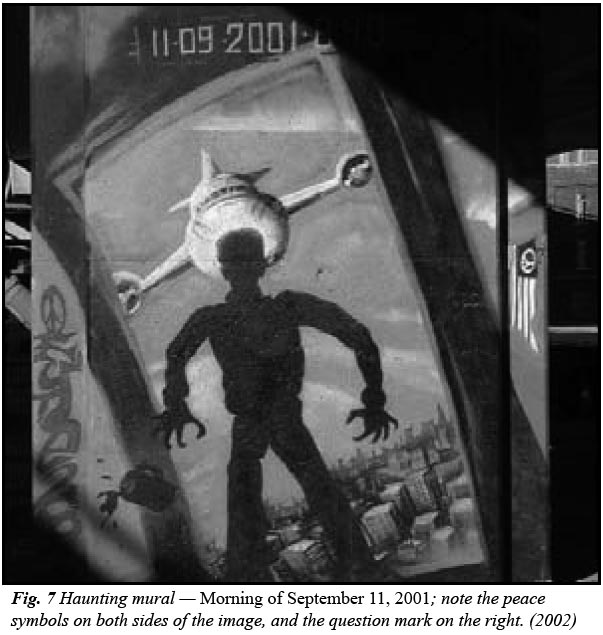

Display large image of Figure 411 In contrast to the erection of stone and bronze public monuments, the anonymous graffiti murals beneath the overpasses of Saint-Roch are marked by the use of vibrant colours, relatively sophisticated designs, and a post-nationalist discourse. These images began to appear sometime in the late 1980s as part of the spread of "graffiti subcultures" mimicking the anti-establishment street art emerging out of the Afro–American neighbour hood experience of the Bronx in the 1970s.19 According to Durand, in 1991 a community group of artists, "faced with the inertia of the municipal authorities and the inappropriate character of some of the developments [urban renewal] in the area…decided to take charge of a site in the Saint-Roch district in order to bring it to life and manage the empty zone."20 That "empty zone" comprised the over passes of the Dufferin– Montmorency Highway. The group, and the empty zone, came to be known as the Îlot Fleurie, a meeting place of popular resistance where marginal and professional art merged to form a zonart, a zone of contemporary citizen art that today encompasses a community garden, over forty sculptures and numerous graffiti murals produced mainly by local inhabitants. As Durand writes, "community life reigns at the Îlot Fleurie, in contrast to the emptiness and odour of disinfected cleanliness emanating from the adja cent large-scale sumptuous park" that was built as part of the city’s efforts to revitalize the district.21 Most of the art in the zone has a com mon discourse: the concerns of the proletariat, the dispossessed, the de-institutionalised, the poor and recent immigrants. Graffiti writing and images run the gamut from an anti-war monument (Fig. 5), to stencil and pasted renditions of populists leaders such as Che Guevara, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King and the Mahatma Ghandi (Fig. 6). There is even a controversial image of a businessman spilling his coffee in surprise as an airplane careens towards the twin towers of the World Trade Centre in New York on the morning of 11 September 2001 — a mural that disturbingly questions the connection between terrorism, war and capitalism (Fig. 7).

Catalysts of Community Action and Resistance

12 From a spontaneous local affair, the Îlot Fleurie’s reputation as an urban site of democracy and artistic creation quickly moved from a regional, to a national, then an international scale. In 1998, writes Durand, the Îlot "comprised a community garden with some 250 different plants and thirty or so sculptures …The libertarian nature and community spirit of…the Îlot Fleurie’s activities [took] art off its podium and put it back into daily life."22 In 1999, the Canadian National Film Board produced L’armée de l’ombre (The Shadow Army), a documentary on the tensions between government decision makers and marginalized people (itinerants, runaways, punks and other street youth) that was partly filmed under the Dufferin–Montmorency Highway.23 Then, in April 2001, thousands of persons assembled there as part of a "monster" protest against the Summit of the Americas held in Old Quebec.

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5 Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 6 Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 713 One of the protestors at the summit, Chantal Bayard (associated with the Comité-Femmes Villeray [Women’s Committee of Villeray], and the Comité-pauvreté du Conseil communautaire Solidarités-Villeray [Community Poverty Committee of Villeray], in Montreal), provides us with a poignant anecdote demonstrating how, by the year 2001, the Îlot Fleurie had taken on the signification of a "People’s Place." Along with her group, she came to Quebec to dissent against globalization. As a result of the violence of the Seattle Summit some months before, authorities constructed a security wall around much of Old Quebec City to limit the movements of protestors coming to stage a "People’s Summit" in contrepoint to the official summit. When exchanges between demonstrators and police became strained:

14 In a spontaneous fashion, the "expropriated citizens" had deployed graffiti murals and messages to transform the "totem poles" of Saint-Roch from iconographic symbols of state domination into catalysts of community action and popular resistance. As a therapeutic means of dealing with impoverishment and disenchantment with the status quo, the graffiti beneath the Dufferin–Montmorency Highway transformed the world and word of the street into a dialogue, a means of "utopian transformation" for marginalized groups who basically saw themselves as the flotsam and jetsam of a consumer society. By the time the smoke had cleared from the Summit of the Americas, it was impossible for city authorities to ignore the community role the Îlot was playing in Saint-Roch. In 2003 an agreement was reached with the city, giving the "Groupe Îlot Fleurie" the right to use the area underneath the highway. Yet this protocole d’entente came at a price. While the city had engaged itself to support the community’s activities, it also dangled before the Groupe Îlot Fleurie a promise to invest some $25 million in the Îlot for the construction of the "Place de France," a commemorative park intended to feature an immense monument, a circular walk, water fountains and stairway to the Upper City, to be finished for the city’s four hundredth birthday.25

15 The future of the Îlot Fleurie is unclear. While the city has recognized the role of the "totems of Saint-Roch" as an organizing element in the community, many city councillors would like to see graffiti activities in the city, which have been on the rise in public places, limited to the highway underpasses. Already, a partner of the city, the CCNQ (founded in 1995 with the mandate to embellish the city, promote its history and improve its stature as capital of the "nation" of Quebec) has since 2000 been sponsoring the creation of "aesthetic" murals on the highway supports of the Îlot Fleurie. Some question, however, if these new murals (beautiful European-looking designs — yet totally mute in message) are not a "foot in the door," a form of beautification, of State co-opting, of gentrification of the iconographic signification that the Îlot Fleurie has come to represent (Figs. 8, 9 and 10). In the face of this problem, one skeptic, Nicola Pezolet, proclaimed:

Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 8 Display large image of Figure 9

Display large image of Figure 9 Display large image of Figure 10

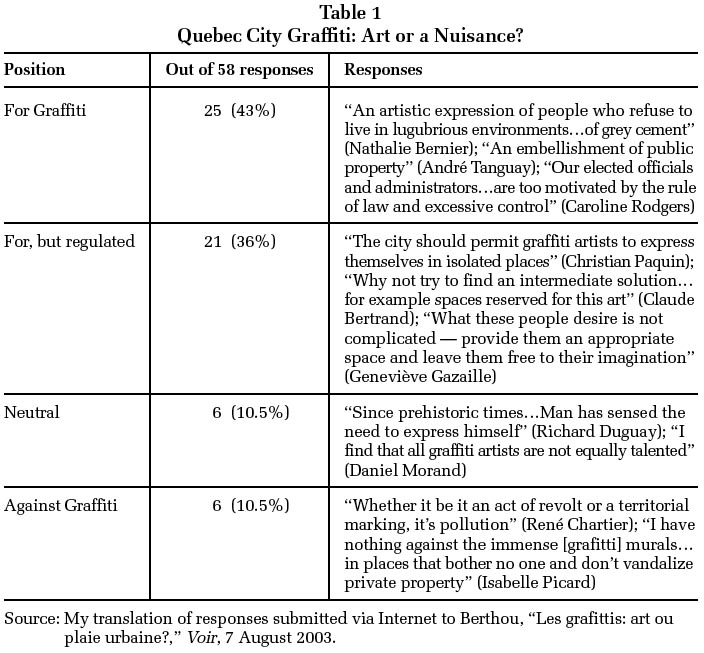

Display large image of Figure 1016 Not surprisingly, a majority of the citizens who read and respond to Voir, a popular alternative cultural magazine of urban issues in Quebec, are in agreement with Pezolet. It is apparent that the Saint-Roch murals have made a tangible impact on how residents of different socio-economic strata across the city view graffiti as playing an integral role in the freedom of expression in the urban milieu. Analysing the fifty eight responses to a Voir article in August 2003 by Yasmine Berthou, "Les graffitis: art ou plaie urbaine?" (graffiti: art or nuisance?), 43% responded that graffiti is an important part of the material culture of Quebc City that should be regulated as little as possible, 36% felt that it should be encouraged but relegated to isolated areas, 10.5% were neutral on the issue and only 10.5% clearly saw graffiti, and its often anti-establishment message, as a public nuisance (Table 1).27

Conclusion

Distinctions between high and low culture and art have become blurred in recent years. As a medium of discourse, graffiti is as old as Pompeii and as potent as the imagery of so many recent democratic uprisings against oligarchies. Whether one accepts this form of communication aesthetically or intellectually, the street art of Saint-Roch is a concrete example that graffiti has become an important part of the material culture and patrimoine of the urban landscape, playing an undeniable role in landscape organization and management (Fig. 11). Display large image of Table 1

Display large image of Table 117 As Denyse Bilodeau argues, only a metropolis whose walls speak is a true city. "Graffiti is life!" she exclaims, and many artists purposely chose this manner of expressing themselves — "they are artists in their soul, they just happen to use walls as their canvas because it offers them a patronage of choice."28 The question now faced by the city of Quebec, and for that matter Montreal and Toronto, is how to deal with this non-traditional form of material culture.29 In the meantime, the erection of monuments goes on in the city. The CCNQ continues to fulfil its mandate of promoting and preserving the history of Quebec City, but the question remains, Whose history? and How should it be preserved? While a bust of the now nearly forgotten nation-builder Louis-Hippolyte Lafontaine was erected in November 2003 in the Old City, did it matter that at the same time an FLQ graffiti, painted in memory of the ideals of a group of national "de-constructors," was replaced by a medieval-looking mural? Perhaps, instead of having a "Place de France," there should be a monument noting that this same location was une place de résistance during the alternative "People’s Summit" in 2001.

Display large image of Figure 11

Display large image of Figure 11