Articles

"Swee-ee-et Cán-a-da, Cán-a-da, Cán-a-da":

Sensuous Landscapes of Birdwatching in the Eastern Provinces, 1900–1939

Abstract

Birdwatching emerged as a popular Canadian pastime as rapid industrialization and urbanization encroached on rural and wilderness landscapes at the end of the nineteenth century. This paper analyses birdwatching as a bodily engagement with place and a sensuous transformation of material setting into landscapes of personal and collective identity. Focusing on the development of activities such as Nature Study and "camera hunting," we argue that birds linked people to specific places and that these relationships helped (re)define national identities and landscapes in eastern Canada. In attending to ways in which sensuous experience of birds has been informed by normative and nationalistic discourse, we also begin to trace the imaginative and moral geographies that have "placed" birds in idealized landscapes, protected zones and categories such as "native" and "foreigner."

Résumé

L’observation des oiseaux est devenue un loisir populaire au Canada lorsque l’industrialisation et l’urbanisation ont empiété sur les campagnes et les paysages inexplorés à la fin du XIXe siècle. Cet article examine ce passe-temps sous l’angle du rapport physique avec un lieu et de la transformation par les sens de cadres matériels en paysages d’identité individuelle et collective. En se concentrant sur l’émergence d’activités telles que « l’observation de la nature » et « la chasse aux images », les auteures soutiennent que les oiseaux ont relié les gens à des endroits déterminés et que ces liens ont contribué à (re)définir identités nationales et paysages dans l’Est du Canada. En considérant les façons dont l’expérience sensorielle vécue avec les oiseaux a influencé les discours normatifs et nationalistes, elles relèvent les géographies morales et imaginatives qui ont « placé » les oiseaux dans des paysages idéalisés, des zones protégées et des classifications en oiseaux « indigènes » et « étrangers ».

Animating Landscapes

1 "When a solitary great Carolina Wren came one August day and took up abode near me and sang and called and warbled the old days," reflected American bird enthusiast John Burroughs (1837–1921), "the old scenes came back again, and made me for the moment younger by all those years." According to Burroughs, "the birds link them selves to your memory of seasons and places, so that a song, a call, a gleam of color, set going a sequence of delightful reminiscence in your mind."1

2 In eastern Canada, early-twentieth-century bird-watchers were expressing similar sentiments in popular bird books and magazines, extolling, in records of bird encounters, a reverence for childhood places, home and nation. Nature lovers took to the fields, marshes, forests, and urban gardens in search of "views" of colourful songsters while "taking in" or embodying the surrounding landscape. This paper re-imagines this activity with a particular sensitivity to sensual geographies, to a living world approached in relation to places that were heard, seen, and experienced bodily. For Kirsten Greer,2 a recent worker amongst the bird collections at the Royal Ontario Museum, such sensitivity offers us a way to "reanimate" and reassess material culture and material landscapes.

3 If, as W. J. T. Mitchell states, landscape should be approached as a verb rather than a noun, "a pro cess by which social and subjective identities are formed,"3 then we would suggest that birds have played an important (and often overlooked) role in animating that process. Historian John P. Turner (1879–1948) made the same point in the Canadian Geographic Journalin 1934: "To envisage a countryside without its birds is to picture a desolation, a cheerless, silent abode of man, unadorned, unattended and unsung."4 We argue that embodied, historical practices of birdwatching involved senses and sentiment, as well as a popular discourse on birds that often contained normalizing directives for proper Canadian conduct and "feeling" toward particular landscapes. In the same article, Turner also rallied the readership with identifications of unnatural behavior: "Strange is the person who experiences no emotional reflections from the birds along rural walks of life."5

4 This paper examines some of the ways birds linked people to specific places of eastern Canada in the early decades of the twentieth century, and how these relationships helped (re)define nationalistic Anglo-Canadian identities and landscapes. We begin by acknowledging birdwatching as not just about "watching" but as a multi-sensuous experience and the birdwatcher as a material body that remembers, reacts, and sensuously perceives place and other human or non-human bodies. This is, in part, a non-discursive historical body which "pauses with alarm at the absence of a particular sound, and knows from a change in the breeze that a storm is coming down the valley."6 Not only did bird watchers observe, listen, and collect birds; they embodied landscapes by absorbing the weather, season, and habitat. Through embodiment, birdwatchers were able to remember childhood excursions or the first sighting of a species on their list.

5 Senses are key in processes of remembering (and forgetting), involving life experiences as diverse as the terrors of war or the resonance of music.7 In the late 1800s, Marcel Proust (1871–1922) theorized the impact of nature’s sounds or "music" on memory in his unfinished novel Jean Santeuil (1952) by claiming that the music of nature holds vividly "the charm of the very hour, the very season, the very country scene in which it caught our attention."8 A bird’s song can evoke a memory of an other place or time, such as the "cries of the departing swallows when the early frosts have come" or the "clear call of the Meadowlark," which was, for Dominion ornithologist Percy Algernon Taverner (1875–1947) "often the first indication of the coming of spring."9

6 Although recognizing and respecting the non-discursive, remembering body, we here highlight the historical body informed by pedagogy, practice, discourse, text, and image.10 "Seeing" and "hearing" the difference between species required a knowledge of the different plumages, songs, and behaviours, which could be learned from a range of living and/or literary sources, including other birdwatchers, popular books, museum specimens, photographs, and field guides in the early twentieth century.11 Recreational birdwatching may be understood then as a field practice influenced and informed by the material and cultural practices of a particular place and time. As recent work in animal geographies12 and the social construction of the senses13 tends to demonstrate, "[w]hat counts as ‘nature’ and our experience of nature (including our bodies) is always historical, related to a configuration of historically specific social and representational practices which form the nuts and bolts of our interactions with, and investments in the world."14

7 A number of studies detail the development of ornithology and birdwatching in Canada;15 however, none have dealt with the sensuous aspect of the pursuit. This paper critically examines birdwatching within a Canadian context during a period of gradual change and transition in birdwatching practices and national identities. In attending to ways in which sensuous experience of birds has been informed by normative and nationalistic discourse, we also begin to trace the imaginative geographies that "placed" birds in certain landscapes, and in categories such as "native" and "foreigner." In terms of its material history, we understand landscape not as a static entity only to be "seen" or "viewed" but rather as a verb that "does things" — a materialization of lived and living experience that engages all of the senses. We here introduce some ways in which "birders" in eastern Canada have engaged with place and have sensuously transformed material setting into landscapes of personal and collective identity.

Cultures of Nature: Boys, Borders, Camera Hunting

8 Twentieth-century Anglo-Canadian birdwatching emerged out of the British and American natural history traditions of collecting birds with a gun and amassing taxidermy specimens for study and display. With the rise of the bird protection movement, the creation and enforcement of laws restricting the hunting of birds, and a gradual shift in birdwatching aims from collection to life-history documentation, these ornithological practices eventually overlapped with a renewed approach to the activity that encouraged the less materially consumptive activity of observing birds in the field with binoculars and cameras.

9 Although our focus here is on Anglo–Canadian birdwatchers who lived mainly in urban areas, we do not suggest they were the only group involved in "birding" activity. Many bird enthusiasts residing in rural settlements of eastern Canada often observed the local avifauna as it related to agriculture and changing environmental conditions. However, we were struck by the considerable urban, white, mostly middle- to upper-class, interest in birds in the early twentieth century.16 This enthusiasm was stirred to some degree by the back-to-nature movement that emerged as a backlash to rapid industrialization and urbanization at the end of the nineteenth century and was influenced by Social Darwinian ideas of "racial health," "overcivilization," and "emasculation."17 "Modern" society had presumably feminized the male, weakened the body, and dulled the senses. Relying on youth to secure a "healthy" future, especial investment was made in young boys. As C. J. Atkinson, a YMCA promoter, claimed in an article entitled "Mother Nature and Her Boys" published in The Ottawa Naturalist, "unnatural surroundings and conventionalities of city life dwarf the boy physically and narrow his mentality, and that to have the boy at his best they must counteract the influences of man-made environment by getting him back to Nature."18

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 110 To prevent the mind from becoming weaker, outdoor excursions such as birdwatching provided "sensory stimuli, which cause brain function, and consequently brain power."19 The Nature Study movement became an important vehicle to awaken an interest in birds for "our future citizens to better enjoy their surroundings."20 By 1908, Nature Study classes had been introduced into public schools across Canada,21 and were intended to train children to see, hear, and understand the natural world, preparing them for active life and citizenship. As J. W. Hotson, Principal of Macdonald Consolidated School in Guelph, stated in 1904, "[i]n training the eye to see, the ear to hear, and the mind to perceive, we have done much to aid the child in understanding the more complex things in real life."22

11 However, popular interest in bird protection was not igniting quickly enough for some observers. Belying a long history of cross-border exchange between American and Canadian ornithologists, the American National Audubon Association even criticized Canada for not taking important steps towards bird preservation by the turn of the twentieth century. In a report of the National Committee for 1904, Bird-Lore critics declared, "strange to say, it has been impossible to establish any close relations with our neighbors on the north, nor is it evident that Audubon work has taken much hold there."23 The Musson Book Company in Toronto would publish American bird books for Canadian audiences, such as Canadian Birds Worth Knowing written by Neltje Blanchan (1865–1918), to embrace "an ever-widening circle of new friends."24 (Fig. 1). Consisting of selected writings from her numerous books, including Birds Every Child Should Know (1907), the book contained descriptions of various bird species as "saints and sinners," and females as "bustling" housewives or "shirking" mothers.

12 The American popular discourse on birds, defined largely by the northeastern urban elite, constructed birds based on "Christian ornithology" (or the "Mother Goose Syndrome") that classified "good" and "bad" birds according to standards of Victorian morality and their usefulness to humans.25 Good birds were those that mated for life, returned to the same nesting area year after year, preserved the appearance of family unity, and were well-bred. Bad birds, on the other hand, fed on meat and dead carcasses, killed the weak and the helpless, acquired several mates throughout a nesting season, stole food from good birds, nested in other species’ nests, and were ungrateful foreigners.26 Furthermore, non-native birds such as the "street urchins"27 — English Sparrows — often were described with anti-foreigner and elitist sentiments that helped foster a national identity that revered country and suburban landscapes.28

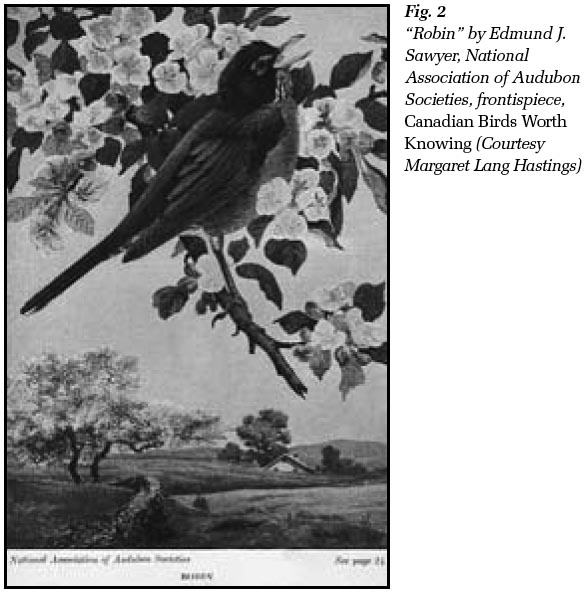

13 Blanchan’s book for Canadians was illustrated with several National Association of Audubon Societies paintings that figured birds in significant landscape contexts. For example, "Robin" by Edmund J. Sawyer (Fig. 2), who would become Chief Naturalist of Yellowstone National Park in 1924, is set in a rural, rolling landscape, inhabited, fenced and tended with fruit trees in blossom. Attractively depicted in an idealized rural setting, the image communicated that not only was the American Robin worth protecting, "of all our birds, ‘the most native and democratic’,"29 this was a landscape worth preserving: the robin belonged here. Similarly, the Barn Owl is placed in a farmyard, Bobolinks are in the meadow, the House Wren sets up house in an orchard and Chickadees, winter residents in the North, play amongst snow flakes against a backdrop of fields and rural dwellings. Interestingly, such detailed place-specific illustrations of birds became outmoded in bird guides after the publication of Roger Tory Peterson’s Field Guide in 1934: his guide introduced a new "game" of bird identification with simplified images of birds in profile, representing his systematized set of distinctive visual signifiers.30

14 Both Blanchan’s and Peterson’s guides reflected changes that were occurring in bird-related field practices in England and North America. Nineteenth-century naturalists operated within the sportsman tradition and "collected" birds with a gun and stuffed their specimens for display and identification. For instance, Thomas McIlwraith, the "father" of Ontario ornithology, published his popular Birds of Ontario (1886, 1894) for an audience that amassed bird collections within the sportsman-naturalist tradition. The 1894 edition included detailed instructions on performing taxidermy and creating bird mounts.31 While some "birders" continued to do so, the new approach involved a "reserved mode of watching and listening"32 employing cameras and field glasses (later, binoculars with higher magnification). The argument for "camera hunting" had been presented in 1900 by the nature-writer, Ernest Thompson Seton (1860–1946), in Rod and Gun in Canada. Seton allowed that the passion to hunt is "natural" in a boy as "he repeats ancestral experience" but, for reasons of conservation and the animal’s "right to life," he advocated the retirement of the rifle: "the weapon is the camera."33 Certainly, the paid professional ornithologist, a relatively new figure in early twentieth-century Canada,34 employed the gun as a scientific tool for specimen collection, albeit with permits after 1917.35 But bird watcher identities were shifting as many birders began to identify themselves as no longer the "sportsmen of the last generation but the bird–lovers of this."36 Robert Kohler notes that "ornithologists were the first biologists to take cameras into the field, no doubt because of their photogenic subjects and their unusually active connection with the world of recreational naturalists" where "home and workplace cultures mingled intimately."37 In particular, bird photography was considered a most suitable hobby for women bird-lovers who were often excluded from the masculine tradition of collecting with a gun and stuffing specimens.38

Display large image of Figure 2

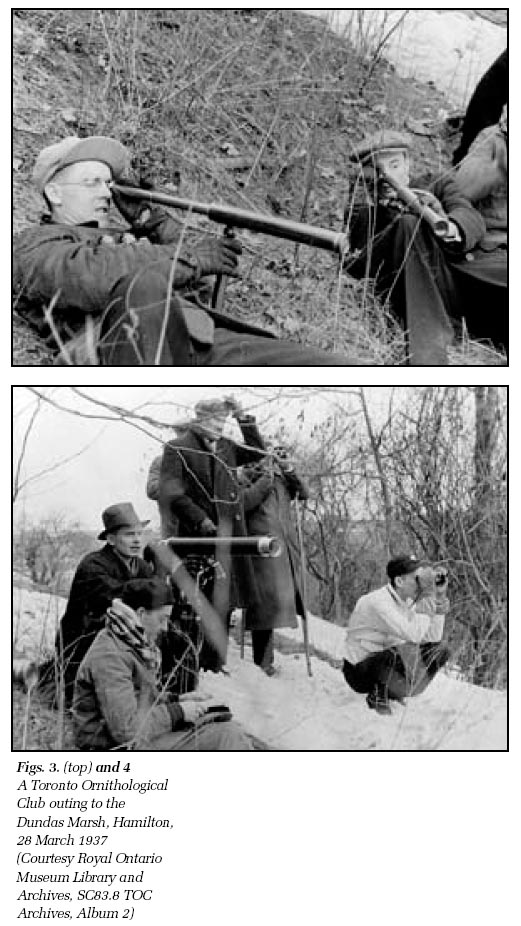

Display large image of Figure 215 Nevertheless, even for those not toting a gun, a continuation of the "collecting" ethic persisted through the employment of photographs and bird lists as observers "stalked" birds for a "view" or to secure the perfect "portrait," which like a stuffed specimen provided material evidence of the excursion.39 On birding expeditions in the 1930s, members of the Toronto Ornithological Club (est. 1934) aimed their large telescopes at the birds they pursued (Figs. 3, 4). Optical technologies such as telescopes, binoculars, and cameras brought nature "closer" and were understood to improve correct bird identification, even enhancing memory. According to early-twentieth-century bird photographer Frank Shutt "[t]he making of a photograph… serves to imprint the image on the memory more accurately, vividly and permanently than does the casual glance at the objects themselves."40 And although hunting with optical equipment rather than a gun might seem to suggest a more benign relation with nature, "camera hunting" signalled a "more subtle though no less powerful mastery"41 through the growing control and management of "birding" landscapes.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3Landscapes Rhythmical and Reserved

16 In making "regular peregrinations about the local area,"42 birdwatchers developed intimate relationships with landscapes and their rhythms. Through the remembering and recording of human/bird encounters, birds became linked to particular places and geographical imaginations. Descriptive accounts often included the weather, time, and habitat while birdwatching illustrated the sensual experience of the excursion. For example, Stuart L. Thompson (1885–1961) and James L. Baillie (1904–1970) immersed themselves "amid the willow tangles" at Ashbridge’s Bay, Toronto, on a "dawned dull and gloomy" morning on 27 November 1927. As they carried on with their adventure, a very small chickadee note drew their attention and the next moment they realized they were "looking at a bird which had no black throat" and "wore a crest. There was no doubt about its [sic] being a Tufted Titmouse," a rare find in Toronto.43

17 The creation of urban parks and suburban gardens helped to open up recreational and domesticated space for birdwatching. Initiated by Frederick Law Olmsted (1822–1903) and Calvert Vaux (1824–1895), city parks, which incorporated the rural countryside into the city, offered opportunities for middle- and upper-class women to birdwatch without having to go into the woods by themselves. Jack Miner (1865–1944) was a pioneer in bird preservation, and his creation of the first bird sanctuary in Kingsville, Ontario, in 1904 inspired the efforts of Naturalists’ Clubs in Vancouver and Ottawa to have public parks set aside as bird preserves.44 In May 1909, a young girl, the future ornithologist Margaret Howell Mitchell (1901–1988), observed a male Northern Cardinal in Toronto’s High Park and later claimed that it prompted a life-long interest in birds: "The sight of it is clear in my memory as though it was yesterday."45 Although the garden was often a feminized space, men also sought its regenerative attributes through the animated bird life which, for some enthusiasts, possessed the power to transcend the nature–culture distinctions associated with particular places. As A. C. Tyndall rhapsodized, "garden or wilderness, as you will, is a favorite place of resort and residence with the lesser fowls of the air…Here may be seen the tiny kinglet, with his voice like the note of an elfin horn; here the scarlet tanager flashes his military looking figure across the open spaces."46

18 Many of these birdwatchers developed an interest in birds and attachment to place during their childhood in eastern Canada. For the enthusiast, the first bird species to elicit a response was a particularly special memory. John P. Turner noted that, "if you are an average Canadian you will probably recall, as each recurring summer swings round, some of your initial meetings with the wild creatures of the countryside…the earliest adventures through fields and woodlands."47 Sir Wilfrid Laurier (1841–1919) recalled the birds of his youth in Arthabaskaville, Quebec, with vivid memories of a species’ plumage, song, nest, and colour.48 Ernest Thompson Seton remembered his first contact with the Eastern Kingbird as one of the earliest of his "wild-life thrills": "This was really a historic day for me, for the event focussed my attention on the brave little kingbird. Always a hero–worshipper and a wild-life idolater, I took the kingbird into my list of nobles."49

19 Such memories underlined a tension between innocence and experience highlighted by the "listing" practice itself. It was the "first sighting" that was so important: it was not considered "listing" and, once "listed," lost significance for the birdwatcher. Louise de Kiriline Lawrence (1894–1992) shared this view during her first year at Pimisi Bay circa 1939: "A new bird, correctly identified, added itself to the last one on my list… However, with the loss of novelty I found myself inclined to lose interest in the new bird. I concentrated all my attention on looking for the next unknown bird that might be lurking in the bushy entanglements, just waiting for me to record it. This is the great danger of ‘listing’."50

20 Rambling haunts, therefore, became memorable places of wonder and excitement, as birdwatchers, especially men, grew older. Their old "‘scouting’ and ‘collecting’ grounds" on the outskirts of towns represented masculine space for "discoveries" and "novelties." For Seton, the farm and backwoods of Stony Creek, Ontario, a site near Lindsay where his family first settled, encompassed "all the loved world of wild things, the kingbirds in the orchard, the robins by the barn, the swallows in the stable, the phoebes in the cowshed, the flicker on the dead tree."51 In Toronto, the Don Valley was "a happy land of bosky hills and open meadows, abounding in bobolinks; and meandering down between, among them, was the winding River Don, vocal with sandmartin, flicker, kingfisher, peetweet, and occasional ducks."52

21 When travelling to distant places, Canadian bird watchers often associated the birds they observed with those from "home," and referred to them as feathered "friends" in times of homesickness. John Clifford Higgins (1889–1969) wrote in his journal, "Early one Sunday morning in Winnipeg, the morning after my arrival, I heard the White-throated Sparrow whistle…it was like meeting an old friend from home."53 Home, for Higgins, was London, Ontario. During the First World War, birds served as a constant solace and comfort during times of chaos and stress for many Canadians. Many enthusiasts observed the birds in England and France while serving overseas in the Great War. E. W. Calvert wrote to his brother about the over "sixty species being noted, and many interesting remarks made about their habits, songs," often hearing comparisons "of the European group with our North American."54 The president of the McIlwraith Naturalists’ Club in London, Ontario, recited a letter from Higgins who, having served in France, recounted "seeing a flock of large birds attacked by aeroplanes, the sight furnishing an interesting display of the powers of flight in both."55

22 As observers become attached to certain birds and landscapes, birdwatchers advocated not only to protect the birds, but also the sensual experiences and memories of their bird encounters: thus bird conservation involved the protection of places and particular times, and, therefore, their self-preservation. Based on economic and aesthetic considerations, Canadian sanctuaries fell under the jurisdiction of the Parks Branch to secure national wildlife conservation although several provincial organizations such as the Federation of Ontario Naturalists (est. 1931) and the Quebec Society for the Protection of Birds (est. 1917) helped establish sanctuaries in eastern Canada.56 Point Pelee National Park was created in 1918, and what had been a home for Aboriginal families less than sixty years earlier became a gathering place for Anglo–Canadian amateur birdwatchers and professional ornithologists.57 Sanctuaries also became places of common cultural ownership where local naturalist and bird protection groups fought to maintain childhood places, first sightings, and feathered friends, which they documented in journals, diaries, photographs, and lists: "The teetering sandpipers on the sand-ribbed beaches, the unsuspected brood of bluebirds in the old apple orchard, the dead basswood where the flickers dwelt, the first partridge that roared upward from your path — some such intimacies of by-gone days will be among your cherished portions of remembrance as you wend your way along the years."58

Shaping Nationalistic Perceptions and Soundscapes

23 In 1901, the Ottawa Field Naturalists’ Club (est. 1879) noted that, "if we, as a nation, can learn to love Nature and to interpret Nature, we shall be certain to make the most of natural resources."59 Canadians in the early-twentieth century were witnessing breaks in British imperial links and the emergence of a self-governing nation, more confident in its attempts to control its water, minerals, forests, and wildlife. Often modelling their ornithological and conservation efforts after their American counterparts, the creation of a number of federal bodies to oversee Canada’s avifauna helped to establish a national focus on birds. In 1900–04, the Geological Survey of Canada published the Catalogue of Canadian Birds, following earlier works in botany and geology that were considered to be of more primary concern.60 The Canadian Parks Branch of the Department of the Interior was created in 1911 and the National Museum of Canada was established the following year.61 Professionals like Taverner helped shape public perceptions of birds as well as scientific field practices.62 As Dominion ornithologist at the National Museum of Natural Sciences in Ottawa from 1911 to 1942, Taverner was an important figure in establishing ornithology in Canada by accumulating national collections of birds at the museum and by studying their distribution through a network of people who collected specimens and gathered ornithological information across the country.63

24 The concern for birds gained strength in the second decade of the twentieth century as Canadians began to recognize and be concerned with "the rapid disappearance of forest birds, prairie birds, field birds, shore birds, sea birds, birds of plumage, native and foreign."64 In 1915, the founding of the Canadian Society for the Protection of Birds heralded a national, albeit short-lived, bird protection movement in Canada.65 Wildlife habitats decreased alongside rapid industrialization and urbanization, while the rampant millinery trade and commercial hunting exhausted North America’s avifauna.66 The loss was understood by the Canadian Parks Branch partly in utilitarian terms: "with the disappearance of our birds, the destruction of the natural wealth by insects forges to the front as a subject of vital importance…each woodpecker is worth about $20 in cash. Each nuthatch and chickadee is worth $5 to $140."67 In 1917, the Canadian government passed the Migratory Birds Convention Act, which bird conservationist Jack Miner declared the "greatest steps between ‘Miss Canada and Uncle Sam’."68 But in terms of such spatial and legislative measures, we must be mindful of the question "protecting what for whom?" Although the Act instigated important conservation mechanisms, it did not consider or compensate the Aboriginal Peoples of Canada whose livelihood and culture depended on Canada’s avifauna. As Stephen Bocking writes of the Act’s pernicious effects, "in these and other ways, such as in portrayals of the landscape by artists, the Aboriginal presence was removed, transforming Canada from a place long inhabited to an unoccupied frontier awaiting colonization and the imposition of a new economic and moral order."69

25 Now actively invested in birds, the Canadian government hired several officers to administer the Migratory Birds Convention Act throughout Canada. Chief Federal Migratory Birds Officer of the Maritime Provinces, Dr Robie W. Tufts (1884–1982) recorded 679 convictions during the first thirteen years.70 Canadian Parks Branch, Department of the Interior, published several works concerned with popularizing and protecting birds. Inculcating a sense of national pride based on economic ornithology, a booklet entitled Birds: A National Asset (1926) stressed the importance of preserving "a heritage of priceless value."71 The Parks Branch even produced two reels of motion pictures entitled Bird Neighbours in Winter and Bird Neighbours in Summer, shot in 1924 by a photographer from the Department of Trade and Commerce.72 Birds thus were promoted as "feathered friends" and aesthetically pleasing to the general public. "Canada has the great good fortune to be peculiarly rich in bird life…few subjects have attracted so much popular attention as birds and few forms of life appeal so strongly to the aesthetic sense."73 As the Department of the Interior explained in Lessons on Bird Protection(1923), "birds make excellent friends. They are interesting, and they respond rapidly to kindness and protection. Many are bright and beautiful in appearance, others delight us with their songs, and nearly all our small birds are useful in destroying harmful insects, or weed seeds, or both."74

26 Literature produced by government officials, education practitioners, and naturalist groups worked to inspire proper appreciation of birds through the "training of the senses." Popular bird books published in Canada included Chester Reed’s (1876–1912) pocket Bird Guide (1906), Taverner’s Birds of Eastern Canada (1919), and William T. MacClement’s New Canadian Bird Book for School and Home (1915). Certain bird species were understood to epitomize specific landscapes: the Lark Bunting, "a bird of our most southern and open prairies" and the Scarlet Tanager, "a bird of light woodlands, where large timber grows with a sprinkling of small underbrush below"75; the Rock Wren, "the very spirit of the mysterious bad lands" of Alberta and the Loon that "adds so much to the satisfactory wildness of our summer camping sites."76 Colourful birds added to the visual experience of landscape with "the dashing orioles, rich fiery orange" and the male Lazuli Bunting, "a veritable living jewel, that flashes in the sun."77 Similarly, the sonic landscape was invested by bird song, with melodious Vesper Sparrows "lisping their evening lines" and the American Bittern adding its peculiar note, "as of some one driving a stake with a wooden maul into soft mud."78

27 Professionals such as Taverner and Hoyes Lloyd (1888–1978) disseminated information about Canadian birds for recreational groups such as the Girl Guides, the TUXIS Boys Club, and the Writers Club. On 3 March 1924, Lloyd spoke to the Scout Leaders in Ottawa on "the protection of mammals and birds" stressing the wanton destruction of Canadian birds and the national landscape.79 He declared, "man has so altered the face of our country in any even[t] that the next generation of Canadians will scarcely know what Canada looked like to the people of our day."80 Other illustrated lectures included the Annual Meeting of the Ottawa Women’s Canadian Club and free presen tations on "Birds and bird protection" at the Victoria Museum in Ottawa. According to Lloyd’s personal notes, "boys and girls would be more active in protecting the birds as they learned about them and found the great value that the birds were to all of us."81

28 In Nature Study lessons, field exercises included listening to the American Robin’s song by distinguishing between "sweet or harsh," "loud or low," and "cheerful or gloomy," as "many persons spend their lives surrounded by singing birds, yet they never hear their songs."82 The robin was seen as a great subject for nature-study work as it was the most "endeared to the people of Canada than any other bird."83 Anna Preston, a Montessori teacher who lived in Clarkson, Ontario, painted and wrote about birds and their habitats for the children in her community (Fig. 5). Field naturalist clubs and bird protection groups such as the Province of Quebec Society for the Protection of Birds (established in 1917) and the Hamilton Bird Protection Society (established in 1919) helped to teach the local community about the birds in their area in newsletters, talks, and outings.84 The Federation of Ontario Naturalists helped young people form nature clubs across Ontario as one of the "more valuable forms of public service which one may render to his community."85 Primarily a professional, middle-class, and masculine domain, such clubs realized earlier aspirations to enable citizens to "hear and interpret the music of Nature’s orchestra, the birds, the bees, the winds, the brooks, to aid in our study of the scenery and to encourage us to learn whatever may be known of the actors."86

29 This new aural attention inspired debate as to which bird species were to be considered characteristic of Canada. The White-throated Sparrow emerged as Canada’s national symbol because of his distinctive song: "‘Sweet, sweet Canada, Canada, Canada’…He utters it because he rejoices in having again reached his home, the place in which he was born and where he hopes to raise his own little family in the coming season."87 Neltje Blanchan, in her Canadian Birds Worth Knowing, noted that New Englanders heard not "Swee-ee-et Cán-a-da, Cán-a-da, Cán-a-da," but rather the distinct sound of "I-I-Péa-body, Péa-bod-y, Péa-bod-y-I, extolling the name of one of their first families."88

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 430 Many Canadians too refuted the notion that the White-throated Sparrow was Canada’s special bird. Certainly, Jack Miner had strong opinions on the matter:

Miner, born in the United States, also compared the Canada Goose with the American Eagle by proclaiming that "our Canada Goose is far superior." Moralizing the bird, he professed that the Canada Goose "will settle down to raise a family, of from four to eight, as all Canadians should. Wild geese pair for life. I never knew them to even make an application for divorce."90 Other bird writers compared Canadian bird species with those from Europe during a time of incipient nationalism. As W. T. MacClement advised, "The two Canadian species [Cuckoos and Kingfishers] are of somewhat better habits than those of other countries."91

31 The European Starling (Starnus vulgaris) eventually replaced the ubiquitous English or House Sparrow as the most unpopular "non-native species" in Canada as it took over native songbirds’ nesting sites in North America.92 Approximately sixty birds were released in New York City’s Central Park in March 1890 by a New York Shakespearean Society that aspired to introduce to America all bird species mentioned by the playwright. The Starling spread rapidly across the continent, eventually reaching Canada by the 1920s.93 The month of November 1927 marked the "first observa tions of the European Starling in the vicinity of Quebec, P.Q."94

32 Conceived as an alien species, the Starling was rendered doubly suspect by being associated with human-altered environments: European Starlings congregated in suburban areas, often middle-class Anglo-Canadian space, "ruining" the appearance of aesthetically pleasing gardens, and diminishing the value of homes. Writing as Dominion ornithologist, Taverner asserted in a letter to Mrs Grant of Stittsville, Ontario, 21 April 1939, that the species "has some very black marks against it and could it be altogether eliminated from our bird fauna there would be general rejoicing." In listing its crimes, he wrote "the worst charge we can bring against [it] is its dirtiness about buildings and monopolizing possible nest cavities required by other birds."95 Even Canada’s bird protection societies loathed the bird and professed that the species "will be replaced, at least in the suburbs, by the native birds, our own beautiful songsters."96

Coda and Call

33 As a practice and experience, birdwatching has been shaped by the social norms and material cultures of particular places and times. In early-twentieth-century eastern Canada, the sensuous and moral geographies of "birders" helped "place" birds in idealized landscapes, protected zones, and conceptual categories such as "native" and "foreigner." Although this paper has sought to make a number of general claims concerning the connections between senses, "birding" and material landscapes, the excerpt above from Elizabeth Enright’s 1957 classic, Gone-Away Lake, suggests that we proceed with caution. Linking people, importantly children, to specific landscapes, places, and times, birds have been a means to animate identifications with specific places, and even associations with nations, and, further, their putative ideals.

34 But for birdwatchers, they also have been many other things, as well as the subject of much debate. "Which birds?" and "for whom?" emerge as key questions that have different answers depending on what imaginative geographies are under consideration. Close engagement with local, regional and provincial scales and specific bird species likely would reveal different cultures of nature. Nevertheless, we hope this paper offers an exploratory indication of the potential richness of approaching the history of birds and birdwatching in Canada with both cultural and geographical sensibilities. As affective shuttles between earth and sky, past and present, birds have long been entangling humans in bird habitats, transforming them into powerful sensual landscapes.

We would like to thank Mark Peck of the Royal Ontario Museum, the Museums of Mississauga, the Canadian Museum of Nature, and Joan Winearls of the Toronto Ornithological Club for all their help in the preparation of this paper. Thanks go to our anonymous reviewers for suggestions and criticism, and to Brian Osborne for comments, encouragement and patient support. Margaret Lang Hastings (1903–1998) provided materials and inspiration and Annsophie (born between the start and end of this project) put it all in perspective. We have endeavoured as best we could to trace the copyright holders of the artwork, both published and unpublished; if any readers can aid in doing so, we will be very grateful.