Exhibit Reviews / Comptes rendus d'expositions

Cool ’60s Design/Design à gogo

S. Holyck HunchuckCollaborating Institutions: Canadian Museum of Civilization-le Musée Canadien des civilisations, Design Exchange, Confederation Centre for the Arts, Canadian Clock Museum, le Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec, Library and Archives Canada-Bibliothèque et Archives Canada, and Canadian Broadcasting Corporation-Radio Canada

Venue: Canadian Museum of Civilization-le Musée Canadien des civilisations, Gatineau, Québec

Curator: Alan C. Elder, Canadian Museum of Civilization-Musée Canadien des civilisations

Designer: Amber Wampole, Amberbrook Designs

Duration: February 24 to November 27, 2005

Tour schedule: To be announced

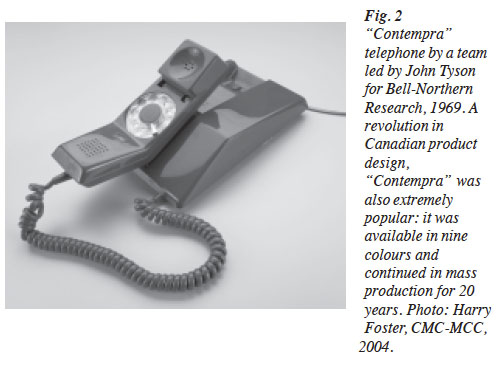

Cost: Free with Museum admission ($10)

Accompanying publication: Alan C. Elder, ed., Made in Canada: Craft and Design in the Sixties, with essays by Sandra Alfody, Paul Bourassa, Brent Cordner, Douglas Coupland, Bernard Flaman, Rachel Gotlieb, Michael Prokopow, and Alan C. Elder. Preface by Douglas Coupland. Forewords by Samantha Sannella and Victor Rabinovitch. Introduction by Alan C. Elder. 128 pp. No Index. Illustrated with photographs by Harry Foster et al. Montréal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press for the Canadian Museum of Civilization and the Design Exchange, 2004. $39.95. Also available in French under the title Fabriqué au Canada: Métier d’art et design dans les années soixante

Accompanying Websites: www.civilization.ca; http://media.civilization.ca/2004/60s_e.html; www.cbc.ca/archives/60s; www.cbc.ca/artspots; and www.radio-canada.ca/archives/annees60

1 Industrial design can be defined as the process of the conceptualization and manufacture of everyday objects, as well as the finished objects themselves. The practice of industrial design is a complex one that requires expertise in fine art practice and theory, as well as an understanding of ergonomics, psychology of perception, the physical and chemical properties of materials and the details of manufacturing processes. It encompasses three-dimensional object design—such as ceramics, furniture and appliances—as well as two-dimensional design—such as, typography and graphic design. Toronto art curators Peter Day and Linda Lewis call industrial design “the art in everyday life.”1 That is, we are surrounded by objects of industrial design (for example, the layout of this page is a piece of industrial design). Accordingly, our dayto-day lives can be as enlivened and enriched by the art of well-designed objects as it can be diminished and even harmed by poorly designed ones.

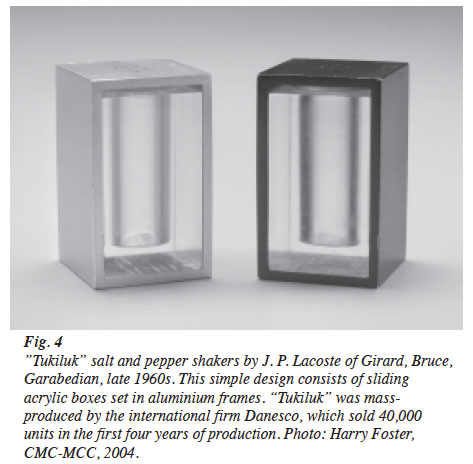

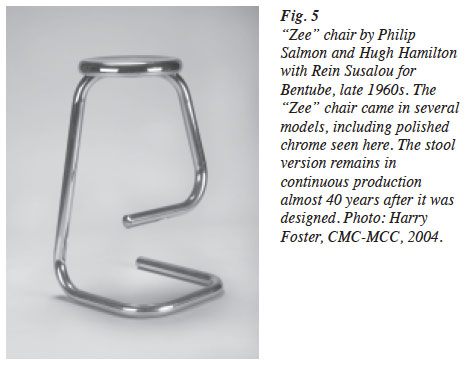

2 Because of its importance in everyday life, industrial design should merit the serious attention of material and other historians, yet its history has seldom been the subject of either academic study or of museum display in Canada, let alone popular appreciation. This has pointedly been the case for products made in this country. As Day says in 1988, “[industrial d]esign has never been fully embraced by the government of Canada, the provincial governments, Canadian industry in general, or the Canadian consumer in particular.”2 More recently, Rhona Richman Kenneally notes in these pages in 2003 that industrial design is an “under represented field of Canadian culture.”3

3 The Canadian Museum of Civilization-le Musée Canadien des civilisations (CMC-MCC) at Gatineau, Québec has begun to address this gap in Canada’s material history through its recent hiring of Alan C. Elder as the museum’s first curator of industrial design. As a trained art historian, Elder is a fine arts aesthetician with a specialty in handi-craft, but he is also interested in modernism as well as the sociopolitical undercurrents behind the promotion of industrial products.4 He curates the Museum’s annual Saidye Bronfman fine craft awards, has overseen exhibitions of post-War modern architecture and interior design in British Columbia and his award-winning thesis on Kitimat, BC, combined a Queer perspective with architectural history.5 Clearly, he is a material historian with broad experience and a unique perspective.

Cool ’60s Design/Design à gogo

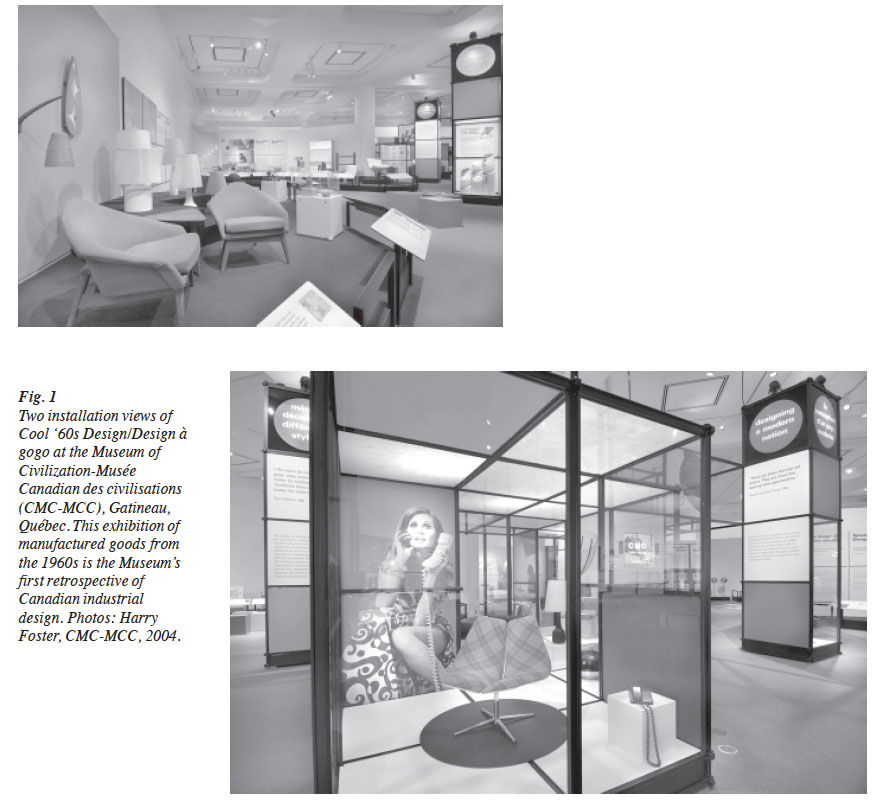

4 Elder’s Cool ’60s Design/Design à gogo is one of a series of museum shows curated by art and architectural historians in Ottawa and Montréal in 2004 and 2005 that examine aspects of material culture in Canada during the 1960s.6 Of these, Cool ’60s Design/Design à gogo and its accompanying publication, Made in Canada: Craft and Design in the Sixties comprise the project of greatest interest to material historians, as opposed to historians of visual art, architecture and urban design (Fig. 1).

5 There are several explanations for the current revival of interest in the period among museologists and curators in Canada; for many, the 1960s represented an exceptional period with many rapid changes. Victor Rabinovitch, President and Chief Executive Officer of the CMC-MCC notes, the 1960s was an “exceptional time ... years of dynamic change,”7 and, as Ottawa journalist Christopher Guly writes in an on-line review of Cool ’60s Design/ Design à gogo, “[u]nshackled after the post-War conformity of the 1950s, the decade was marked by the rise of civil rights and individual liberties, spawning an optimism about both the present and the future.”8

Fig. 1 Two installation views of Cool ‘60s Design/Design à gogo at the Museum of Civilization-Musée Canadian des civilisations (CMC-MCC), Gatineau, Québec. This exhibition of manufactured goods from the 1960s is the Museum’s first retrospective of Canadian industrial design. Photos: Harry Foster, CMC-MCC, 2004.

Display large image of Figure 1

6 Second, these changes were manifest in material culture, and by examining the objects in retrospect we can more fully understand both them and this historical period. Added to the sociocultural context of dynamism and confidence described by Rabinovitch and Guly, was a period of prolonged economic growth and relative prosperity. These conditions led to novel material culture. Consumers in the 1960s not only had the means to buy new, modern products but in so doing, could acquire a cachet of progressiveness and cosmopolitanism; that is, the “coolness” associated with the broader cultural trends of the era’s music, politics and social relations.

7 Third, in terms of purely materiality, the period is marked by novel fabrics used in innovative ways. Recently-developed materials including plastics, aniline dyes, chrome and aluminium introduced into mass use after 1945 were well-established by the 1960s. Also important were myriad styles and fashions associated with variants of modernism. Designers around the world in the years after the Second World War, including Canadians, were predisposed to the severity and orthogonal lines of International Style Modernism first promoted by American and European avant-gardeists in the 1920s. However, important alternative influences were the shiny surfaces and streamlines suggested by the Space Age mentality, and the curvilinear forms and luxurious treatment of materials, whether expensive teak or inexpensive plastic, of Scandinavian romanticism (popularly known as “Danish Modern”). By the latter half of the 1960s, the counterculture also shaped design. A return to ornament through bright colour and floral decoration was captured by the period phrase, “Flower Power,” while back-to-the-earth artisans revived handicrafts in natural materials such as clay and jute. These led to widespread changes in the 1960s—to the ways everyday objects looked, felt and functioned. The objects of the era expressed a new attitude towards prosperity and materiality and advanced a new spirit of pleasure, to be derived from the consumption of new goods and in their aesthetic qualities.

8 Guly characterizes it as the “colour burst” era, where the everyday palette of manufactured objects suddenly expanded to include neon pigments and other vivid colours used in contrasting and dramatic ways. Elder cites as an example the “Contempra” telephone, by John Tyson and a design team at Bell Northern Electric in Ottawa. This 1969 product was a functional sculpture, rendered in bold colours and striking angles (Fig. 2). As Elder notes, until “Contempra,” “telephones had been stuck on a wall or on a desk and were just tools for communication. Tyson’s group moved the telephone to become something that was more a part of everyday life,” designing it in nine high-gloss colours including yellow, mauve and bright red, instead of the standard black.9

Fig. 2 “Contempra” telephone by a team led by John Tyson for Bell-Northern Research, 1969. A revolution in Canadian product design, “Contempra” was also extremely popular: it was available in nine colours and continued in mass production for 20 years. Photo: Harry Foster, CMC-MCC, 2004.

Display large image of Figure 2

9 Fourth, the practice and forms of industrial design have undergone many changes since the 1960s. For some museologists, the time has arrived for a retrospective of this era. In Elder’s view, “post-modernism [prominent in design from c. 1980 to the mid-1990s] broadly degraded the modern project [and] we can now reconsider many aspects of the sixties in Canada by looking at the material culture that has been left behind.”10

10 Finally, there is also a definite though hard-to-define nostalgia for this era that, arguably, began with the Massey Commission’s recommendation of 1951 that the Government of Canada “forge and project a Canadian culture,” and which reached its zenith at Expo 67.11 Rabinovitch argues that the 1960s were “a golden age for Canadian designers who were clearly among the most talented and imaginative in the world.”12 His claim may at first appear to be exaggerated—until the museum-goer who enters Cool ’60s Design/Design à gogo sees some of the classic pieces of the era. These are mounted as iconic artifacts in museum display cases, they are all Canadian in provenance and all are evocative of a recent history remembered fondly by many for its faith in the power of modernism to create a better world.

11 Cool ’60s Design/Design à gogo is a significant exhibit. In terms of museum history in Canada alone, this temporary show of Canadian, mass-produced three-dimensional objects is the CMCMCC’s first exhibition on the subject of industrial design from Canada, and the first industrial design show generated in-house by the institution. It is an ambitious project that involves significant loans from the Design Exchange of Toronto (DX), Confederation Centre for the Arts, Charlottetown, PEI, the Canadian Clock Museum of Deep River, Ontario, and le Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec. Contextual data on the politics and the sociocultural aspects of the 1960s are suggested on-site by broadcast and webcast multimedia presentations created by additional partners, including the CBC Radio Canada Archives, CBC Halifax, Library and Archives Canada-Bibliothèque et archives Canada (LAC-BAC), and consultant Mario Girard, a Montreal musicologist. Additionally, Made in Canada, the exhibit’s accompanying publication, is a joint effort between the CMC, DX and McGill-Queen’s University Press.

12 The items on display in Cool ’60s Design/ Design à gogo range from items as commonplace and inexpensive as the “Contempra” phones and Julian Rowan’s 1962 “Thermos” flasks for the Canadian Thermos Company, to high-end museum pieces (Fig. 3). The higher end is represented by such late 1960s classics as J. P. Lacoste’s “Tukiluk” salt-and-pepper shakers, and the curvilinear chrome tube “Zee” chair by Philip Salmon and Hugh Hamilton with Rein Susalou (Figs. 4, 5). All are functional objects, minimalist in form and clearly industrial in origin, yet artful at the same time. “Tukiluk,” for example, consists of clear transparent acrylic boxes that fit into the hand and slide into brushed aluminium frames, while the sinuous “Zee” chair is redolent both of organic forms and shiny, Space Age technology. Many of the 150 other items in the exhibition also demonstrate that at one time Canadian designers and manufacturers possessed a sense of visual flare, ergonomics and tactile appeal: these were sculptures made to be visually appreciated, but also held and used. That they incorporated functional use with extremely high production values (such as finely polished surfaces or seamless joints, even in the plastic items) no doubt contributed to their success with both the design community and ordinary consumers. “Contempra” for example, was put into mass production for twenty years, and the “Thermos” came in seven colours and was manufactured for thirty years. “Tukiluk” sold 40,000 pairs in its first four years, and the stool version of the “Zee” chair line continues to be produced almost forty years after it was first designed.

Fig. 3 “Thermos” insulated flask by Julian Rowan for the Canadian Thermos Co., 1962. The classic design was produced in seven colours and manufactured for 30 years. Photo: Harry Foster, CMC-MCC, 2004.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 5

13 Another artifact of note is the Canadian-made “Q-bit” display system used in the exhibition. With its array of slender black members arranged in a three-dimensional grid, it is a modular system reminiscent of the steel skeletons of high-rise buildings. Its simple, logical and unobstrusive form allows for a neutral and spacious display area for individual items and shows them to great effect. The installation of these colourful, once-familiar objects in Cool ’60s Design/Design à gogo is, in purely visual terms, simple and severe. In effect, the CMC-MCC aestheticizes them. In so doing, the museum has elevated what might have once been seen as the merely everyday, banal and disposable to sort of votive object. For the viewer, such an approach allows the artifact to become a starting point for the meditation of a cluster of other historical and aesthetic issues, such as the role of rational problem-solving vs. ornamentation in design, the difference between the products of the 1960s versus those of today and the role of the museum in displaying and interpreting them for the general public. “Q-bit” was designed in-house at the CMC-MCC in the late 1980s by Amber Walpole and others, and to see it revived for use in this show is arresting. From the threshold of the exhibition, we are subtly reminded of the structural coherence and simple elegance of modernism at its International Style best, which did not disappear entirely during the period when postmodernist attitudes otherwise flourished (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6 “Q-bit” display shelving units by Amber Walpole et al for the CMC-MCC, late 1980s. This simple modular system is severe and unassuming, and forms the perfect fit for 1960s artifacts. Photo: Harry Foster, CMC-MCC, 2004.

Display large image of Figure 6

14 Interspersed among the artifact installations is a background of different audiovisual media intended to provide a sense of context. Together with the artifacts, these are loosely organized among three themes: “Designing a Modern Nation,” “Canada Welcomes the World” and “Same Decade, Different Styles.” The first describes the federal government’s initiatives to articulate Canada as a modern and progressive nation and the role industrial design played. The largest and most familiar of these projects were the 22 airports built by the Canadian government between 1952 and 1970. These were grand projects, both in terms of scale and artistic endeavour, where airport terminals were meant to function also as public art galleries showcasing the best of modern Canadian painting, sculpture, interior design and furniture design. Robin Bush’s “Lollipop” seating system of black vinyl and black tubular steel, designed for the Toronto International Airport in 1963, stands as a visual symbol of these initiatives (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7 “Lollipop” chairs by Robin Bush for Canadian Office and School Furniture Co. and the Toronto International Airport, 1963. Made of steel tubes and hardware, plywood, foam and black vinyl, this seating ensemble was part of a much larger design programme for Canadian airport interiors and furnishings. Photo: Harry Foster, CMC-MCC, 2004.

Display large image of Figure 7

15 Another phase of the Canadian government’s one-time support for design is explored through Expo 67 in “Canada Welcomes the World,” the enormously popular World’s Fair mounted by the federal government in Montreal in 1967 as a celebration of Canada’s Centennial. This pivotal event is marked by a period short film from the CBC Archives and an array of Expo 67 memorabilia; such as, slipcast ceramic platters, signage and plastic ashtrays (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8 Expo 67 ashtray. Plastic, c.1966. A typical example of memorabilia featuring logos from the World’s Fair held in 1967 at Montréal as a celebration of Canada’s centenary. Photo: Harry Foster, CMC-MCC, 2004.

Display large image of Figure 8

16 The third component, “Same Decade, Different Styles” suggests how the “rise of technology, identity politics and social activism inspired distinctly different designs during that turbulent period.”13 This aspect of the show is perhaps the weakest, with an overemphasis on context through suggestion and atmosphere, rather than on clear definitions of ideas or explanations of their purpose in shaping industrial design during this period.

17 The display’s mass appeal, with some 250,000 visitors from the end of February 2005 to the middle of October 2005, may make it the most popular exhibit of industrial design mounted in Canada in the 38 years since Expo 67. Such statistics indicate that the time represented a coming-of-age for many, including curators and museum programmers such as Elder, as well as appealing to the general public.14 With Cool ’60s Design/ Design à gogo, the CMCMCC seems to have tapped into a desire among the public to see or revisit these once-familiar objects and to view them in an interpretative framework in which material culture is treated as fine artifacts as well as expressions of broader cultural trends. For Canadians over a certain age especially, walking through this exhibition can invoke more than visual pleasure in form and colour. For some there will be the intellectual satisfaction of instant object recognition, as well as a sense of poignancy for the lost possibilities of the immediate past. These beautiful, once-familiar objects were designed and built in Canada and most of us have used them at some point, but took them for granted, and discarded them with little thought. This unintentional elegiac note may cause the viewer to ask: when did Canadian design loose this sense of vibrancy, cleverness and affordability? We are left to ponder what has happened to Canadian industrial design, and to museology, in the decades since Rabinovitch’s “golden age.”

18 In terms of design, many have considered Expo 67 to be a highlight and source of inspiration. However, Norman Hay, Expo 67’s design director said in 1988 that it had not been the beginning of a new era, but rather the end of one. Expo had been a synthesis and exegesis of the concerns for good design that had marked the post-Second World War era. In the decades that followed ... these concerns did not grow and become an integral part of Canadian life and culture. If anything, the millions of Canadians who went to Expo 67 had been impressed that Canada could put on such an exhibit, rather than being impressed by the standards that so distinguished this World’s Fair.15In terms of museology, much has changed since museum practice of the 1960s. The model for Cool ’60s Design/Design à gogo is similar to that of the CMC-MCC’s Canada Hall-Salle du Canada, a much larger and permanent exhibit. In it, historical artifacts are embedded in a busy matrix: rather than a static and silent display area, the Canada Hall-Salle du Canada is a multimedia installation involving broadcast videos, sound effects and interactive computer screens.

19 This approach has both strengths and considerable weaknesses: it is ambitious in the museum setting, and it results in as much attention paid to the suggestion of sociopolitical context as it does to the description of the materiality and provenance of the objects on display. At its best, it can animate an exhibition space and make for a lively kinesthetic; however, it can also cause an atmosphere of excessive noise levels and other sensory bombardment where context is relentlessly suggested but never fully explained.

20 Two desktop computers with access to the CBC Digital Archives and one from the LAC-BAC are installed in the centre of Cool ‘60s Design/Design à gogo, featuring period documentary news shorts and other archival footage curated by CBC staff members Tom Metuzals and Marie Tetrault. Described by the CBC as “an on-line archive showcasing moments from Canada’s past” and as “a collection of [video] clips ... that are witness to the visionaries, issues and events that have shaped Canada,” this part of the exhibit alone would take hours and multiple visits to peruse, but they appear to be a sample of period “soft” news: typical are such items as a rambling first-person documentary through Yorkville (a downtown Toronto neighbour-hood that was a centre of 1960s counterculture) and snippets from a chat show discussion of women’s undergarments.16 A giant screen showing a continuous loop of the Expo 67 film is mounted nearby. At the middle entrance, additional television monitors broadcast a continuous videomontage of news soundbites, edited by Mary Elizabeth Luka of CBC Halifax, and running at repeated 14-minute intervals. Playing overhead on another continuous loop is Girard’s soundtrack of the greatest hits of Canadian popular music of the 1960s.

21 The purpose throughout the show is to suggest Canadian events as a backdrop to the objects proper. While this is a laudable idea, the real strengths of the exhibit lie primarily with the artifacts and their visual installation, and not with the wall-to-wall audiovisual collage of broadcasts, webcasts and soundtracks—all offered simultaneously in a small exhibition space and without any acoustical impedance separating one sound source from another. While background context is important because objects on their own do not tell the entire story, the cultural and political events of the 1960s are well-documented and readily available in many other sources, including any textbook of 20th-century history. However, the industrial design of the period is considerably less documented, which is why exhibits of this kind are essential. That is why, for those interested in material history or museology, the background makes Cool ’60sDesign/Design à gogo a frustrating experience. The music, newsreels and archival footage installed throughout provide more than audiovisual context: they can be overwhelming and distracting. The result in the exhibition, as in the Canada Hall-Salle du Canada, is a sense of excessive noise, data glut and sensory overload that detracts from the pleasure and contemplative opportunity offered by the objects proper. Such a museological approach actually works against material and visual literacy: there is simply too much broadcast “stuff” and too many layers of it to allow the viewer to see, hear or think clearly at times.

22 This is not the only shortcoming of the exhibit. Size of a given object, its materials, colours available, name and résumés of designers and places and dates of manufacture are all important contextual information, for even the casual viewer. In conventional art historical practice, such information is imparted unobtrusively through wall labels or in a handout fact sheet/list of objects, and explored in depth in an exhibition catalogue. Thus the Museum’s decision to forego a traditional exhibition catalogue for Cool ’60s Design/Design à gogo and to do away almost entirely with conventional “tombstone” labels is doubly regrettable: at the same time the viewer is made dizzy by an atmosphere of continually-broadcast overlays of news footage, soundbites and period music, there is almost no basic information about the artifacts in front of her.

23 The sociocultural contextualization suggested throughout Cool ’60s Design/Design à gogo is better expressed by the essayists in the show’s accompanying publication, Made in Canada, rather than by the audiovisual backdrop to the installation. This important book is a reminder of the value of textual interpretation to the museum experience. While not an exhibition catalogue per se, it stands on its own and is worthy of its own review. It is here that the links between political ideas, cultural events and industrial design in Canada are made clear, with essays by noteworthy curators and art historians including Douglas Coupland, Bernard Flaman, Rachel Gotlieb, Michael Prokopow and Elder himself. They expand with great lucidity on background themes to the objects on display, such as the politics of Canadian airport design, the role of plastics and the significance of global trends and fashions on industrial design in Canada during this period. Cool ’60s Design/Design à gogo is best experienced in conjunction with Made in Canada; however, the book on its own will remain a model for future scholarship in material history long after the exhibit closes. It belongs on the bookcase of every Canadian material historian.

Conclusion

24 Cool ’60s Design/Design à gogo has its flaws; nevertheless, the CMC-MCC is to be commended for producing it and Made in Canada. The dilemma of striking an appropriate curatorial balance between the discussion of sociocultural background versus the discussion of objects proper is not unique to Cool ’60s Design/Design à gogo, nor to the CMC-MCC, but to contemporary museum practice. Similarly debatable is the merit of high-tech solutions to museum interpretation, such as interactive computer screens and audiovisual loops, versus low-tech ones, such as conventional wall labels. In Cool ’60s Design/Design à gogo, the strongest and most compelling components are the artifacts, and these could well have stood on their own, albeit supported by additional signage and labelling.

25 The objects in Cool ’60s Design/Design à gogo suggest that industrial design exhibitions should become regular features of the museum. Perhaps the popular success of the show will inspire the CMC-MCC to mount a permanent sample of 1960s design as an adjunct to the Canada Hall-Salle du Canada, whose narrative of Canadian history currently ends in a Vancouver Airport lounge circa 1970. Additionally, the museum’s programming would be strengthened by instituting an annual industrial design awards show, on a par with its Saidye Bronfman awards for handicraft, and the CMC-MCC could be an ideal venue for retrospectives of such important designers as Bush or for shows centred around landmark pieces of Canadian design. The story of the “Contempra” telephone alone, for example, could fill a dedicated exhibition.

26 Cool ’60s Design/Design à gogo and Made in Canada also contain reminders of the value of real artifacts and relevant text for museum goers and readers. While the high-tech approach employed as supplementary documentation provides the viewer with a huge quantity of data, it can be of limited use and sometimes dubious quality: superb images by Harry Foster of some objects in Cool ’60s Design/Design à gogo are available on the CMC-MCC website (and are reproduced here); other data are of such poor quality as to be hard to follow and can be practically unwatchable. The excerpts from the CBC Archives for example, seem random in content and provisional in form, with the Yorkville segment webcast in slow, jerky fragments with pixels as large as pencil erasers. Not only is it physically difficult to watch, but its content is confusing and its relevance to design open to question.

27 The visual treatment of industrially-designed forms as fine art objects in Cool 60s Design /Design à gogo is a welcome one. However, the aesthetic experience of the show would be enhanced by a fuller return to conventional art historical practice, at least in terms of wall labels and an exhibition catalogue. Additionally, material literacy in Canada would be advanced by the inclusion of simple artists’ biographies, and chronologies of design and manufacturing firms. A glossary of materials would also be invaluable for students of modernity and of material history: is the transparent plastic found in so many products of the time “Plexiglas” or “acrylic”? (They are fundamentally the same thing, with the former a proprietary name for acrylic in solid sheet form, but the viewer has to undertake independent research outside the exhibit to determine that.)

28 Finally, any future industrial design exhibits at the CMC-MCC would be strengthened by more attention paid to acoustical design. Not only does Cool ’60s Design/Design à gogo contain too much peripheral data to absorb—or merely witness—in one visit or even many visits, the noise levels alone caused by the background installations are too loud, too multi-voiced and too distracting. In some instances, the sounds can be downright annoying: to hear a children’s choir sing Bobby Gimby’s “Cana-da” of 1967 once is to be instantly reminded of the era; to hear it five times in an hour grates on the nerves. These and other background stimuli meant to induce historical context are excessive and dis-orienting at best and ought to be re-examined as museum policy. They can, and do, detract from purpose of exhibits such as Cool ’60s Design/ Design à gogo: that is, to allow viewers to see or revisit the objects of the era, enjoy their variety of colours and forms, and, in so doing, consider for perhaps the first time their visual pleasure, the memories they evoke and the ideas they raise as the material culture of an exciting, idealistic period in modern Canadian history.

Notes