Research Reports / Rapports de recherches

Showcasing the Military Aviation Uniform Collection at the Canada Aviation Museum

Bill ManningCanada Science and Technology Museum Corporation

1 The mandate of the Canada Aviation Museum (CAvM) is “to illustrate the development of the flying machine in both peace and war from the pioneer period to the present time [with] particular but not exclusive reference to Canadian achievements.”1 Consequently, its collection of aviation clothing represents a broad range of activities both civilian and military. CAvM is not a “war museum,” nor is it a museum of military aviation history per se, so it follows that the collection of air force uniforms is relatively modest in size.2 The assemblage nevertheless includes interesting artifacts that illustrate the development of uniforms worn by the flying services in which Canadians made a significant contribution.

Collection History

2 The National Aeronautical Museum, which opened in 1964 at Uplands Airport in Ottawa, was an assemblage of aircraft and related artifacts from three sources: trophy aircraft collected following the First World War and later acquired by the Canadian War Museum (CWM), military aircraft maintained by the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) following the Second World War and the National Aeronautical Collection of airplanes relating to civil aviation and bush flying created at the National Research Council (NRC) in 1937. When the National Museum of Science and Technology (NMST) was created in 1967, the combined collection was absorbed into its Aviation and Space Division. In 1982 this was renamed the National Aviation Museum (NAM). In the devolution in 1990, the National Museums Corporation (NMC), which was responsible for the administration of all federal museums, was dissolved. The National Museum of Science and Technology Corporation (NMSTC), later renamed the Canada Science and Technology Museum Corporation (CSTMC) became an independent crown corporation. NAM, later renamed the Canada Aviation Museum (CAvM) became one of its three component museums, along with the Science and Technology Museum and more recently the Canada Agriculture Museum.

3 The focus of the aviation collection has always been, and remains, aircraft and related technology. Little in the way of flying clothing and uniforms was acquired before 1967. An examination of surviving documentation on old NMC and NMST Acquisitions and Collections files shows that from 1967 to the end of the 1970s, uniforms donated to the aviation museum were often transferred immediately to the CWM, and potential donors were referred to CWM whenever possible.3 In August 1977, a draft general agreement was drawn up between the National Museum of Man (responsible for the Canadian War Museum) History Division and the National Museum of Science and Technology (which held custody of the National Aeronautical Collection) in an attempt to identify areas of overlap, where they existed, and to identify the museum with primary responsibility. “Uniforms” appears on “List A: Categories where no Overlap Exists,” with the notation that uniforms were to be “collected by each institution relative to its subject areas.”4 For whatever reason, the agreement was not ratified and the discussion was put on the back burner for a number of years.5

4 In 1980 the CWM distributed an insert in veterans’ pension packets, asking them to consider donating their uniforms and other militaria. The results surpassed all expectations as several thousand donations were received that year.6 At around the same time, the NMC conducted an exercise to revise its Collection Policy. One clause that generated considerable discussion was intended to address collection duplication among all of its component museums. In essence, it stated that while some overlap among the collections was necessary and even desirable, overlap in acquisitions created competition for artifacts among the museums, and this was to be avoided; objects— once acquired—could be shared. Due to the complexity of the subject the policy did not address specific collection areas, but NMC management encouraged the development of bilateral agreements between museums where there were areas of common interest.7

5 Accordingly, Dr. William McGowan, Director of NMST, and Dr. George MacDonald, his counterpart at the National Museum of Civilization, along with select members of their respective senior curatorial staff, scheduled a meeting for September 7, 1984, to discuss finalizing an agreement.8 The meeting was to take place over lunch, so it is unlikely the intention was to do more than simply ratify the 1977 proposal. Given that air force uniforms are artifacts of intense interest for both military and aviation history, it seems surprising that they were deemed not to merit any discussion. The military airplanes at the CWM had been reassigned to NAM prior to the creation of NMST in 1967, so it seems likely that a “gentlemen’s agreement” had been reached at that time to the effect that all other aspects of military aviation, including air force uniforms, would remain within the mandate of the CWM, while NAM was responsible for commercial airline uniforms and civilian flying clothing.9 The author has been unable to locate any formal agreement to that effect in the NMSTC Corporate records, but an examination of the artifact acquisitions files shows that until the end of the 1980s, there was at least an informal understanding among NAM curatorial staff to maintain the status quo.10

6 Throughout the 1980s, NAM attempted to avoid conflict with the CWM by excluding military aviation from its interpretation plan as much as possible, and with the Canadian Museum of Civilization by defining aviation in such a way as to emphasize technology rather than people. Another more practical consideration was limited storage space. When NAM opened its newly constructed building at Rockcliffe* in 1988, several interim lots of surplus and duplicate uniforms and flying clothes were transferred from the CWM. (*Rockcliffe, near downtown Ottawa, is the site of a former air force base, at the time maintained separately from the civilian airport at Uplands.) Most of these (RCAF working dress) were used to dress the mannequins in the new exhibition areas. The remainder (predominately RCAF service dress uniforms and jackets) were transferred to the NAM Education Division for use in various interpretive programs.11

7 In the years immediately following the 1988 opening of the new building, a number of important changes occurred. First, a reorganization of NMSTC curatorial responsibilities detached space technology from aviation and grouped it with communications. This was important because the focus on space technology throughout the 1980s had somewhat eclipsed aviation. Because NAM was now a distinct administrative and curatorial component, staff could be hired who were dedicated exclusively to the development of the aeronautical collection. This roughly coincided with the appointment of a new Associate Director of NAM, Christopher Terry. The new administration recognized a broader definition of aviation in its interpretation of the museum’s mandate; hence air force uniforms and associated militaria were viewed as legitimate objects for collection. A second factor may have been the perception—almost certainly incorrect—that with the devolution soon to become a reality, direct insider access to the uniforms at the CWM could no longer be taken for granted. Since NAM possessed little in the way of air force uniforms, its curators began to accept donations of such items and alluded to the possibility of future special exhibits on the subject.12 After the devolution in 1990, NMC policies on collection overlap, bilateral agreements and informal understandings became null and void. A survey conducted by the author on the CSTMC collections data base confirms that the vast majority—in excess of 95 per cent—of the military aviation uniforms and components in the Canada Aviation Museum collection were acquired after 1989.13

Uniforms and Dress Orders

8 According to author Jennifer Craik14 most uniforms are derived from military clothing originally introduced to distinguish opposing sides in battle. Military uniforms were first adopted by officers, but subsequently imposed on all ranks to instill discipline and help train body and mind in specified ways. Military uniforms have always been influenced by contemporary civilian fashions, and military styles have in turn had a strong impact on civilian clothing styles. Generally, military uniforms have been intended to reinforce order, discipline and conformity and to project an idealized masculine image.

9 Military uniforms in the 19th century were often elegant and ceremonial in nature; but impractical for field operations, especially in the tropics. In the years just before the First World War the British and other European armies with colonial experience recognized the distinction between dress and utility uniforms as standard issue. From the Second World War to the present, utility has increasingly gained precedence over tradition in uniform design.15

10 Today, uniforms serve to distinguish service personnel from civilians and from members of other services. For the individual, wearing a uniform reinforces a sense of solidarity and common purpose and is a visible outward expression of pride and commitment. The uniform also reminds him or her that the interests of the individual are subordinate to a set of common goals, hierarchy and discipline. At a broader level, armed forces—and by extension their uniforms—are often used by governments as national symbols to communicate particular aspects of national will and character. They also reflect the dynamics of interservice politics and the status of the wearer. As we will see below, uniforms say a great deal not only about how service personnel see themselves, but how the international community sees their country and the service branch they represent.16

11 Military organizations publish and enforce dress regulations. In general, military clothing can be divided into seven categories. The focus of this report will be the “general issue” uniforms: service dress and working dress. Other categories include mess dress, ceremonial dress, operational dress, occupational dress and specialized clothing.

12 As seen above, by the First World War (1914-18) most military organizations in the western world issued or authorized the wearing of a full dress and utility (undress) uniform. Full dress is an ornate, often brightly-coloured uniform, once worn for a broad range of duties. Today it is retained by the British and Canadian army for ceremonial occasions. Full dress fell out of favour in the navy and air force in the late 1930s because it had to be purchased by the wearer, and many officers could not afford it. The undress uniform, a more functional version of the full dress uniform, was introduced around the turn of the 20th century as a dress/ parade uniform as well and, for every day work and field combat duties. Like full dress, it included a high collar tunic and in the early flying services, included riding breeches and field boots that rose to just below the knee (enlisted personnel wore cloth wrappings around the lower legs called “puttees” with ankle boots). Both officers and “other ranks” usually wore a forage or field service cap with this uniform. Officers wore a Sam Browne belt (a leather belt with one or two shoulder cross straps for sword and sidearm holster) over the tunic. Undress would evolve into service dress and working dress during the inter-war period.

Service Dress

13 The service dress uniform is the military equivalent of the business suit. Today, it is the basic uniform that is most often worn for a broad range of duties and can be worn unrestricted in public—hence it is often called a parade or “walking out” uniform. The jacket is single-breasted and skirted with an open collar, and is worn with qualification and unit badges, rank insignia and ribbons. It is usually worn with a peaked general service cap, dress shirt and neck tie. Khaki-coloured service dress was introduced for officers in British Imperial forces just before the onset of the First World War.17 The overall design was the same as undress, except that the tunic had an open collar to accommodate the social convention that a gentleman was expected to wear a tie in public. Service dress was allowed to be worn by “other ranks” by the Second World War. Service dress uniforms are often available in two variations. Throughout much of the 20th century, British and Canadian air forces issued a dark blue winter service dress and a khaki summer service dress, alternated seasonally. The army issued brown service dress along with khaki drill summer, bush or tropical versions at various times, while the navy retained dress blue and dress white uniforms.

14 The service dress uniform is subject to a range of dress orders, which are combinations of uniform articles that can be authorized for wear depending on the occasion, weather or the nature of the duty being performed. There are about ten dress orders of service dress ranging from very formal to relatively informal. For example, on very special occasions, an RCAF commanding officer may authorize the ceremonial dress order which consists of the winter service dress uniform with peaked general service cap, white gloves, ceremonial belt and shoulder boards, full-size medals and can include boots, ceremonial sword and lanyard. The most prominent aspects of mess order (as distinct from mess dress) are the substitution of a black bow tie in lieu of neck tie and the wearing of miniature medals. Duty dress is the order worn most often for normal day-to-day work. At the other end of the spectrum, an airman or sailor working on an aircraft carrier in the tropics may wear tropical shipboard order, consisting of short sleeved shirt open at the neck, with slip-on rank insignia on the shoulder straps, and shorts patterned after summer service dress trousers (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 This tailored barathea RCAF officer’s winter service dress jacket from the 1950’s (catalogue #1996.0688.1) includes both Flight Surgeon and Paratrooper qualification badges. The wearer was trained to accompany airborne troops into combat zones.Working Dress

15 Working dress evolved from the undress (or utility) uniform and is the military equivalent of civilian work wear. This uniform is worn by personnel performing physical duties where clothing might become soiled, worn or damaged. It has less status than service dress, fewer insignia and is generally not worn unrestricted in public. It is referred to by a variety of terms: called working dress in the RCAF and in the post-unification Canadian Forces (Air Operations). It was sometimes referred to as battle dress during the Second World War. In the contemporary post-unification Canadian Forces (Air Force), it is officially called base (navy and air force) or garrison (army) dress. The Officers’ rank braid is usually worn on the shoulder straps of the jacket. Working dress is designed for physical work or combat and is made in an unadorned, more comfortable design, and of more durable material than service dress. The uniform is usually worn with field service (wedge style) cap and combat boots.

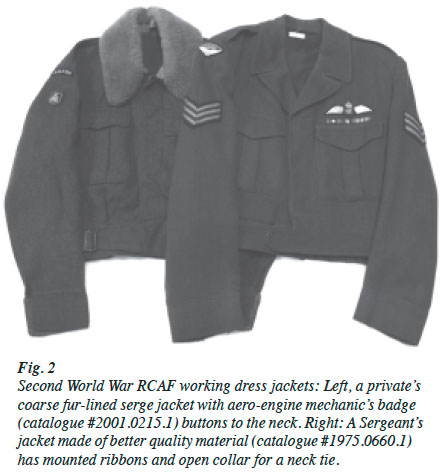

16 At the beginning of the Second World War, the standard issue working dress jacket for “other ranks” was designed with a fall collar and was worn buttoned to the neck. Officers could buy a special issue or have their jackets altered by a tailor to include an open collar so a tie could be worn. This privilege was subsequently extended to enlisted personnel, since many had not been issued service dress, so working dress was their parade and “walking out” order. Since the 1960s, one-piece coverall garments, including light weight flying suits, have increasingly been used as work or combat dress. Technically operational clothing, they can include many uniform elements such as qualification badges and rank insignia (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Second World War RCAF working dress jackets: Left, a private’s coarse fur-lined serge jacket with aero-engine mechanic’s badge (catalogue #2001.0215.1) buttons to the neck. Right: A Sergeant’s jacket made of better quality material (catalogue #1975.0660.1) has mounted ribbons and open collar for a neck tie.Other Categories

17 Mess dress, the military equivalent of a tuxedo, is usually worn by officers for mess dinners and formal military and civilian evening social functions. It was developed in the late 19th century as a lightweight alternative to the heavier and more cumbersome full dress uniform, from the very functional infantry shell jacket (an undress tunic worn in the British Army) and the cavalry stable jacket.18 Like the full dress uniform, it is often very ornate and must be purchased by the wearer (i.e., at no expense to the government). Service dress mess order or navy white dress mess order can be worn in lieu of the mess dress uniform.

18 Ceremonial dress has traditionally been equated with the full dress uniform. In the Canadian Forces, army regiments continue to retain full dress uniforms in their dress regulations, although they are no longer standard issue. Air force personnel wear their winter service dress uniform ceremonial order on ceremonial occasions. Similarly, navy personnel wear the dress white uniform with ceremonial accoutrements on such occasions.

19 Operational dress is a category that includes camouflage clothing, combat helmets, flak jackets and other personal protective gear. Unlike naval and air forces where working dress and combat dress (or battle dress) are effectively the same uniform, armies make a distinction between working dress—called garrison dress in the Canadian Forces (Army) today—and field combat dress. Flying clothing (one and two-piece flying suits, flying jackets, flying gauntlets, flying boots) and flying headgear (flying helmets, goggles and associated communication and breathing apparatus) are issued to air crew in flying services.

20 Occupational clothing is worn by personnel in occupations that by their nature require unique clothing during the performance of their work: police officers, firefighters, cooks and medical staff or an aircraft mechanic’s coveralls. Specialized clothing is usually garments issued for wear in extreme climate conditions—Arctic or tropical wear, for example—or maternity clothing.

Female Uniforms

21 Women’s uniforms evolved from nurses’ uniforms, which in turn were patterned after domestic servants’ uniforms. Craik identifies two types of female military uniform. “Feminized” uniforms promoted traditional attributes of nurturer and helpmate, and predominated among women in military organizations before the Second World War. The most familiar example is probably that of the nursing sister (see Fig. 8).

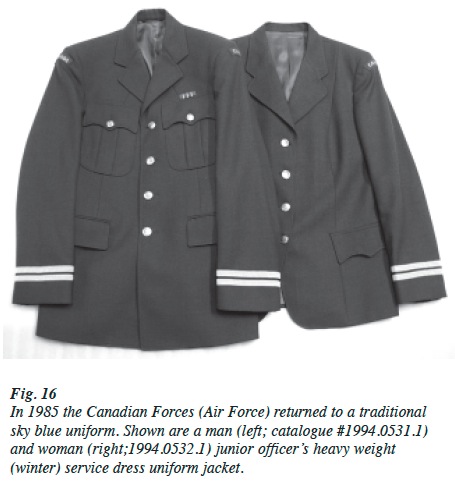

22 The “quasi-masculine” type of uniform became more prominent during the Second World War when women began to enter the armed forces in significant numbers for the first time. While women’s contribution to winning the war was recognized in allied countries, fashion and cosmetics were promoted as morale boosters and equated with values such as hope, courage and patriotism. As author Kathy Peiss19 points out, this placed women under pressure to work like men (both in the military and as war workers) while maintaining their femininity. It is no surprise, therefore, that female military uniforms gave expression to conflicting desires. At one level it was necessary for female personnel to adopt the same overall uniform pattern as their male counterparts to symbolize belonging and a shared purpose, but they still wanted to look like women. Uniforms of the period achieved a compromise of sorts by combining feminized masculine elements with feminine elements (see Fig. 16).

23 A third major adjustment occurred in the 1960s. Traditional female-dominated jobs began to disappear and the military became a more attractive career option. The further expansion of roles for women within the military led to a need for more practical garments, so that distinctions between male and female working/combat dress have been further diminished.20

History of Flying Services and Uniforms

24 Although its origins can be traced to the use of balloons to observe enemy troop positions as early as the Napoleonic Wars,21 organized military aviation occupies a very short period in historical terms, roughly from the First World War to the present. Uniforms worn by Canadian flying services evolved from those worn in the British army, navy and air force. As seen above, military uniforms tend to reflect fashion trends from the broader culture, but another influence was contact with “subject” people throughout the British Empire. For example, Bernard Cohn22 argues that when the British initially recruited locals into military units, they usually introduced some Imperial uniform elements to impose cultural homogenity, but at the same time allowed—even encouraged—distinctive features to preserve the distinction between rulers and ruled. Well known examples are the Scottish kilt and the Indian turban. Later, however, British resistance to distinctive “native” clothing “echoed the growing sense of loss of power being felt by the British as they rapidly divested themselves of the empire ... and heard their former subjects demanding their independence and some form of equality with their former rulers.”23 By the 20th century, these had evolved into national emblems symbolic of the desire for more autonomy.

25 Thomas Abler further notes that Imperial officers often adopted stylized elements of the fighting attire of native warriors.24 He speculates that for British soldiers, being associated with exotic frontier theatres of operation and elite units elevated the status of the wearer in the military hierarchy. Again, well known examples in British and other western armies include Hussar, Highland and Zouave uniforms, the cummerbund (a sash worn with the mess dress uniform) and (as noted above) the khaki uniforms from India. Few exotic uniform features can be found in the military uniforms of the self-governing dominions like Canada, Australia and New Zealand, which were populated largely by people of Anglo-Saxon descent (with the exception of Scottish “Highland” regiments). The wearing of Native American clothing in Canada was common in Loyalist militia during the American Revolution and in the quasi-military British Indian Department until the War of 1812.25 Canadian military uniforms thereafter remained overtly British in overall design. As we will see below, however, a growing sense of nationalism and continued efforts by Britain to shed responsibility for overseas de-fence would quickly lead to the adoption of distinctive national badges.

Royal Flying Corps (RFC)

26 In 1911, the British army created the Air Battalion as part of the Royal Engineers and the Royal Navy opened the Naval Flying School to conduct aerial observation by balloon, airship and airplane.26 The following year the Committee of Imperial Defence created the Royal Flying Corps, which comprised a military and a naval wing. When the First World War broke out in 1914 the RFC Army Wing was sent to France and attached to the British Expeditionary Force to gather intelligence over battlefields—a role that soon expanded to include aerial combat and bombing enemy positions. When the Royal Navy absorbed the RFC Naval Wing to form the Royal Naval Air Service (see below), the Military Wing dropped the sub-title to become the Royal Flying Corps.27

27 The RFC was initially composed of personnel from the Royal Engineers, airship ratings (enlisted personnel) from the Royal Navy, and army personnel seconded from army regiments, who all wore the uniforms of their parent service with RFC badges and insignia added. Since the RFC Army Wing was part of the British Army, it adopted the British Army dress orders, including the standard khaki undress uniform and peaked general service cap, with distinctive brass RFC badges and buttons. Pilot and observer wings were worn over the left breast pocket of all uniform jackets. The standard army ranking system was used; rank insignia consisting of crowns and stars on the shoulder straps or sleeves (army chevrons were worn by NCOs). A Sam Browne belt was worn by officers with both khaki service dress and undress jackets, as were riding breeches with field boots or puttees.

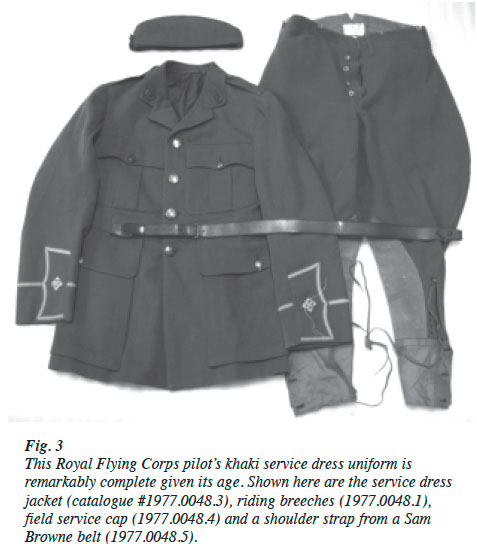

28 RFC dress regulations of 1913 introduced two uniforms based on the traditional pattern of the Royal engineers. The full dress uniform included a dark blue tunic buttoned to the neck, dark blue overalls with red stripes along the outside trouser legs, and a peaked cap with a red band and badge. Mess dress also included a dark blue jacket with a scarlet collar. Also new was the distinctive khaki drab double-breasted “maternity jacket.” This cavalry style tunic, along with the riding breeches and boots, likely reflected the fact that reconnaissance was the role traditionally played by the cavalry. Pilots and observers saw themselves as inheriting that role—literally “knights of the air.” Cavalry experience was considered an advantage for an aviator because the movement of a small airplane was similar to that of a horse. The service dress tunic (later adopted by the RAF) was based on that of the cavalry officer. Dress regulations (1913) introduced a field service cap “in the Austrian pattern” or “wedge” cap28 (see Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 This Royal Flying Corps pilot’s khaki service dress uniform is remarkably complete given its age. Shown here are the service dress jacket (catalogue #1977.0048.3), riding breeches (1977.0048.1), field service cap (1977.0048.4) and a shoulder strap from a Sam Browne belt (1977.0048.5).Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS)

29 When the First World War broke out in 1914, Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty, argued for the development of specialized naval aviation, so the Royal Navy began using aircraft, balloons and airships for reconnaissance and operated a chain of coastal air stations. The men and airships of the RFC Naval Wing were absorbed into the Royal Naval Air Service in 1914 and used for fleet reconnaissance, coastal patrol, attacking enemy coastal territory and defending Britain from air raids. The new service adopted the navy ranking system.29

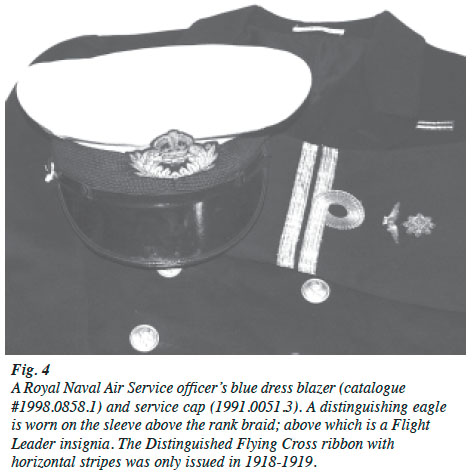

30 Even before coming under naval regulations as the RNAS, the naval wing of the RFC had developed its own dress regulations that included a small gilt eagle on officers’ cap badges and a red embroidered eagle sleeve badge for ratings. RNAS personnel wore the same khaki service dress and undress uniforms as their RFC counterparts, except for the distinguishing eagles and green khaki drab navy-style sleeve rank braid on officers’ tunics. As members of the Royal Navy, they also wore the same blue dress uniforms as other navy personnel, with a distinguishing gilt metal eagle on the left sleeve of the blazer above the gold rank braid, and a cap badge with a centrally-located eagle instead of an anchor (see Fig. 4). The blue uniform was worn in England, while on leave or for ceremonial occasions, whereas the khaki service dress uniform was worn while on active duty in Europe. A distinguishing eagle was also added to the shoulder board of the navy white dress uniform30 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4 A Royal Naval Air Service officer’s blue dress blazer (catalogue #1998.0858.1) and service cap (1991.0051.3). A distinguishing eagle is worn on the sleeve above the rank braid; above which is a Flight Leader insignia. The Distinguished Flying Cross ribbon with horizontal stripes was only issued in 1918-1919.Royal Air Force (RAF)

31 There has traditionally been considerable rivalry between armies and navies. The British Army and the Royal Navy were no exception and this competition naturally extended to their respective flying services. The strategic requirements of aviation in support of army and navy operations were very different. Success in defending Britain from Zeppelin attacks was sometimes compromised because in their flight from their bases in Europe to targets in England, enemy airships crossed jurisdictional boundaries and the RFC and RNAS failed to collaborate on intelligence and agree on interception tactics. Furthermore, the “senior service”—the navy—ignored the Central Flying School and squabbled with the RFC over the limited supply of aircraft and money. Another consideration may have been the perception that as head of the navy, Churchill was attempting to create his own “private air force” in competition with the army and the RFC. The British government concluded that problems of coordination, competition and duplication could be eliminated by amalgamating the two services, so in 1918 it formed the RAF reporting to the newly created Air Ministry.31

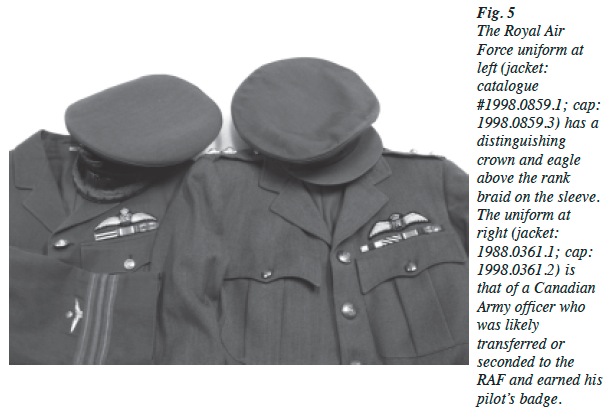

32 At first, RAF personnel continued to wear their RFC and RNAS uniforms. Officers who transferred to the RAF from the British Expeditionary Force, or were on temporary assignment, wore the regimental dress of their parent regiments, but added RAF badges and sometimes buttons (see Fig. 5). The Air Ministry approved RAF dress regulations in 1918 that initially included khaki service dress and undress uniforms. The Air Ministry was determined to eliminate old animosities between the two parent services and establish the RAF as a separate entity, so it adopted conspicuous signs of its independent status. The first uniforms introduced in 1918 were essentially army style khaki with khaki drab navy-style sleeve rank braid and gilt distinguishing eagle. This was replaced by a sky blue uniform for officers later that year.

33 The choice of blue has three likely sources. First was the blue RFC full dress uniform. A second influence was possibly a dark blue patrol uniform32 worn by many RFC pilots toward the end of the First World War, but did not appear in the official dress regulations. A third factor was the unexpected availability of a large quantity of light Ruritanian blue cloth ordered for uniforms of a Russian Cossack cavalry regiment prior to the outbreak of the October 1917 Revolution. The unused (and undeliverable) blue cloth was impossible to dye and was available at precisely the time the RAF was looking for a distinctive uniform pattern.33

34 This design was not popular and was only used for about a year. In 1919, a blue-grey pattern replaced all previous uniforms for all ranks. This pattern, a compromise between the army and navy styles, has remained relatively unchanged. The overall design was reminiscent of the uniform of the cavalry officer, of a colour similar to that of the Royal Engineers and a reminder of the origins of military aviation in the British Army. The RAF adopted distinctive titles based on the navy ranking system (e.g., a Lieutenant [navy] became a Flight Lieutenant) to further emphasize its independent status. The cap badge (a close variation of the Royal Engineers insignia), flying badges worn on the breast of the tunic and brown gloves were borrowed from the RFC, while the distinguishing eagle and blue sleeve rank braid came from the RNAS. The new uniform pattern featured a cloth belt to replace the Sam Browne belt. Both trousers and breeches with puttees (or field boots) were worn initially, but trousers replaced them for service dress in 1939, at which time the working dress uniform, modeled on the army battle dress, was approved for general wear34 (see Fig. 5).

Fig. 5 The Royal Air Force uniform at left (jacket: catalogue #1998.0859.1; cap: 1998.0859.3) has a distinguishing crown and eagle above the rank braid on the sleeve. The uniform at right (jacket: 1988.0361.1; cap: 1998.0361.2) is that of a Canadian Army officer who was likely transferred or seconded to the RAF and earned his pilot’s badge.First Canadian Air Force (RAF No. 1 Canadian Wing)

35 Before 1918, many Canadians had enlisted in, or were seconded to the RFC and RNAS. The government of Robert Borden, re-elected in 1917, proposed the creation of a distinctly Canadian unit within the RFC (Royal Flying Corps), provided it could be attached to the Canadian Expeditionary Force in France. There were several reasons this was desirable. First, Canadian successes, in particular at the Battle of Vimy Ridge, gave rise to new feelings of Canadian nationalism. Canadians comprised more than 25 per cent of the complement of the “British” flying services and were among the most numerous and successful air crew on the western front. The Canadian government wanted a separate command to form the nucleus of a permanent post-war flying service in Canada. There was also the perception of discrimination and lack of recognition of Canadian “colonial” personnel in the RFC and RNAS. Finally, there were the precedents established by the Canadian (Army) Expeditionary Force already fighting as a distinct corps within the British Army in France, and by the Australian Flying Corps formed in 1914. The British government initially declined the proposal, since transferring large numbers of Canadians to a new service would disrupt existing squadrons.

36 When the RAF was created in 1918, it formed a wing (two squadrons) composed entirely of Canadians, designated No. 1 Canadian Wing. That year the Canadian government assumed some responsibility for administering the wing, renaming it the Canadian Air Force (CAF). While the Canadian government was interested in patriating the CAF to form a national flying service, it was not prepared to pay for equipping and maintaining it, and could not decide to what extent it would conduct military (as distinct from civil) aviation. The British government was unwilling to continue to fund the CAF after the war ended, so in 1920 it was disbanded. Some senior officers may have had CAF uniforms by late 1919 or 1920, but most simply wore their RAF uniforms with maple leaf “Canadian General List” cap and collar badges.35

Royal Canadian Naval Air Service (RCNAS)

37 The Canadian government had formed a Department of Marine and a small navy in 1910 for coastal defence. In 1918, at the urging of the British Admiralty, it created the RCNAS to assist with coastal patrol to protect convoys headed for Britain and placed it under the direction of the Department of Marine. Until the new service could become self-sufficient, the British government asked the United States Navy to extend patrols northward to the Atlantic coast of Canada and Newfoundland. The U.S. Navy also agreed to provide seaplanes and pilots until the RCNAS could take over, effectively setting up a U.S. Naval force in Canada, reporting to the Senior British Naval officer in Halifax and working in cooperation with the Royal Canadian Navy, under the overall direction of the RAF and the British Air Ministry. This confusing arrangement “placed Canada in a position of singular dependency.”36 Arguments erupted between the RAF and Royal Navy over which uniform and rank structure was to be used. Intended to exist only as a temporary force until hostilities ended, in 1919 the service was disbanded.37

38 The precise status of the RCNAS was never determined, and tension arose between British officials, who wanted the uniforms to resemble those of the RAF or RNAS as much as possible, and Canadian politicians who wanted the service to have a uniquely Canadian appearance. A Canadian government Order-In-Council stipulated that officers’ uniforms would include a dark blue serge jacket similar in style to the RAF service dress jacket, with RAF rank braid on the sleeves. RAF pilot’s wings, modified to include the monogram “RCNAS” on a centrally-located maple leaf, were worn above the left breast pocket. Again, a Sam Browne belt, riding breeches and field boots were worn. Officers wore a naval-style peaked cap with a maple leaf cap badge. Apart from the cap and sleeve braid, the uniform was very similar to that of the second Canadian Air Force (below): the badges identical except for an anchor substituted for the “CAF” monogram. Enlisted men were to dress like sailors in the Royal Canadian Navy, but to wear a distinguishing badge on the sleeve.38

Second Canadian Air Force (CAF)

39 The Canadian government had little inclination to underwrite a peacetime military aviation service, but remained interested in developing civil aviation. Fortunately, Canada received a gift of surplus war airplanes from Britain, and inherited the aircraft and equipment donated by the U.S. Navy after it withdrew its personnel in 1919 when the RCNAS was disbanded. Canada also had experienced pilots who had recently served in the RFC, RNAS and RAF during the First World War. In 1920 the government created the second incarnation of the CAF, a non-professional auxiliary reservist organization, as a department of the Canadian Air Board.39 The CAF was intended to maintain the flying proficiency of the veteran flyers and train new pilots. In a reorganization of the Air Board at the beginning of 1923, the Civil Operations branch, responsible for civilian aviation conducted on behalf of other government departments, was absorbed into the CAF. At the same time the Canadian government combined the Department of Militia and Defence, the Department of Naval Service (formerly the Department of Marine) and the Canadian Air Board to form the Department of National Defence (DND). The CAF was now a permanent “militarized” service, but retained responsibility for civil aviation.40

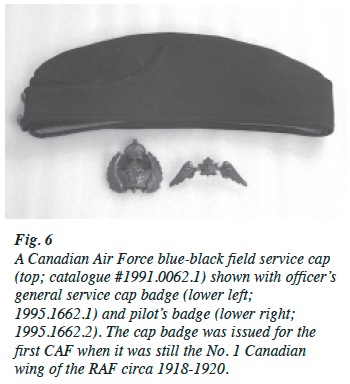

40 CAF members initially wore their RAF uniforms until new ones were issued. Officers wore blue-black service dress uniforms of fine woven wool with distinctively Canadian silver flying badges, cap and collar badges. The Canadian Air Board would not decide whether to use ranks taken from the RFC (army) or RNAS (navy) so both ranking systems were recognized. Army-style shoulder rank insignia consisting of crowns and stars were worn on the shoulder straps. The service dress jacket included the same style of cloth belt as the RAF uniform. Surviving photographs show officers wearing either dress trousers or riding breeches with field boots, depending on the occasion. It has been suggested that the colour was possibly adopted from the navy blue patrol uniform especially favoured by Canadian RFC personnel late in the First World War.41 Both wedge style field service caps (see Fig. 6) and peaked general service caps were worn.42 Khaki-coloured working uniforms and items such as winter coats were provided by the Department of Militia.43 Enlisted personnel wore a service dress uniform that included a Norfolk jacket.44 CAF uniforms were considered unique and stylish for their time, and when seen in photographs are very distinct from their RAF counterparts.45

Fig. 6 A Canadian Air Force blue-black field service cap (top; catalogue #1991.0062.1) shown with officer’s general service cap badge (lower left; 1995.1662.1) and pilot’s badge (lower right; 1995.1662.2). The cap badge was issued for the first CAF when it was still the No. 1 Canadian wing of the RAF circa 1918-1920.Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF)

41 Between Confederation in 1867 and the Second World War, there was ongoing debate between Canadian politicians who wanted Canada, as a self-governing dominion, to maintain a small militia-based army for home defense (primarily against possible attack by the United States), and their British counterparts who wanted a larger more professional regular force to assist with defense of the Empire abroad as part of British-led expeditionary forces.46 To facilitate integration into British units, virtually all aspects of Canadian military organization, including uniforms, copied the British model. This was nowhere more evident than when the RCAF was formed in 1924.47 The RCAF continued to fulfill the civil aviation functions of its predecessor,48 but in a reorganization in 1938 the service became a fully-militarized independent service branch, on “an equal footing with the Navy and Army.”49 The RCAF played a distinguished role during the Second World War, especially in the Battle of Britain and the air war over Germany, as well as operating the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP) in Canada (see below).

42 RCAF personnel served in RAF squadrons, or in RCAF squadrons assigned to RAF commands. When the war ended in 1945, the RCAF was the fourth-largest air force in the world and it continued to be a formidable force throughout the 1950s and early 1960s, helping counter the Soviet threat as members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). The RCAF also assumed a critical role in North American continental defence in partnership with the United States in the North American Aerospace Defence Command (NORAD). Before and during the Second World War, cohesiveness with the RAF had been an important consideration, but in the years that followed, the RCAF increasingly found its activities integrated with those of the U.S. Air Force. Additionally, throughout the 1960s, Canada’s military role included peacekeeping and intervention in smaller conflicts as part of United Nations (UN) task forces. The RCAF remained an independent service branch within the Canadian military establishment until the Canadian Forces unification in 1968.50

43 From the moment the CAF had become part of DND in 1923, it came under the control of military planners concerned with Imperial conformity who had considerable influence in the years before the Statutes of Westminster.51 If the distinctive and stylish CAF (and RCNAS) uniforms had been an attempt to distance those organizations symbolically from their British counterparts and assert a unique Canadian identity, the slate blue uniforms of the new militarized RCAF were virtually identical to those of the RAF, except for the “RCAF” embroidered on the Pilot’s badges and raised “R.C.A.F.” added to RAF pattern buttons.52 In photographs that include members of both services, it is often difficult to distinguish between them unless a pilot’s badge or a “nationality” shoulder insignia is visible. The RCAF adopted the RAF ranking system and rank insignia: navy-based for commissioned officers (e.g., Flight Lieutenant, Group Captain) and variations on army rankings and insignia for enlisted personnel (e.g., Flight Sergeant rather than Staff Sergeant).53

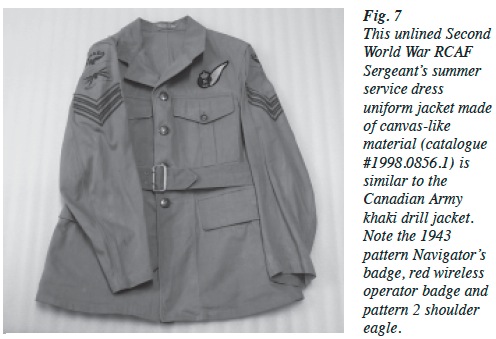

44 Like the RAF, the RCAF issued two seasonal versions of the service dress uniform: a winter service dress made of blue-grey serge or barathea cloth, and a summer service dress of khaki tropical worsted that resembled the uniform worn in the British Army54 (see Fig. 7).

Fig. 7 This unlined Second World War RCAF Sergeant’s summer service dress uniform jacket made of canvas-like material (catalogue #1998.0856.1) is similar to the Canadian Army khaki drill jacket. Note the 1943 pattern Navigator’s badge, red wireless operator badge and pattern 2 shoulder eagle.

Display large image of Figure 7

45 RCAF working dress, which again closely resembled the British pattern and was derived from the army battle dress, was introduced near the beginning of the Second World War to replace dungarees for general wear. The colour was the same blue-grey as the winter service dress uniform. Its basic components were a blouse-style (falling only to the waist) jacket with a full collar and pleated breast pockets, working trousers and long sleeve shirt with sleeves that could be rolled up and secured. The jacket could be secured to the trousers by means of a ring of button holes in the waistband that corresponded to buttons inside the waistband of the trousers—effectively transforming it into a one-piece coverall. The wedge style field service cap and combat boots were normally worn with this uniform.

Fig. 8 This Second World War RCAF nursing sister’s cape (catalogue #2001.0418.1), optional wear with the formal dress(es) white and mess dress uniforms, is dark blue with a bright cherry lining. Note the medical collar badges.British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP)

46 During the Second World War, the RCAF organized and administered the BCATP to train Commonwealth and Allied air crews. One of the most important motivations for the creation of the program was the determination of Canadian Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King that in contrast to the First World War, Canada would have as much control as possible over its own flying services. The RCAF operated flight schools across Canada. U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, in recognizing the BCATP as a significant Canadian (and in particular RCAF) contribution to the Allied war effort, called Canada the “Aerodrome of Democracy.” It provided a uniform system of training and helped ensure that the various Commonwealth air forces could integrate effectively. Graduates were awarded air crew flying badges upon successful completion of their courses (Pilot, Observer, Air Gunner, Wireless/Air Gunner, Navigator, Bomb Aimer, Engineer, Flight Engineer).55

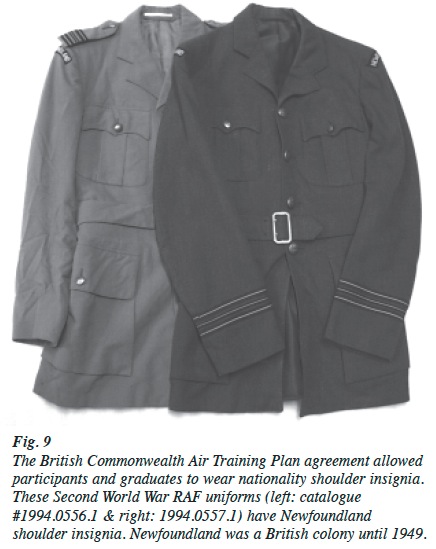

47 Uniforms worn by British Commonwealth air services, including Canada, were similar to RAF pattern service dress and work dress, but the BCATP agreement authorized distinctive “nationality” shoulder insignia to be worn by foreign nationals training in Canada and on active service overseas (see Fig. 9 for examples of RAF service dress jackets with Newfoundland shoulder insignia). The plan also promised the formation of Dominion units within the RAF, but most RCAF personnel continued to serve in RAF squadrons or in RCAF squadrons under RAF operational control for the duration of the conflict. While the RCAF had achieved its objective of integrating well with RAF and Commonwealth air operations, it had little voice in overall strategy and decision making.56

Fig. 9 The British Commonwealth Air Training Plan agreement allowed participants and graduates to wear nationality shoulder insignia. These Second World War RAF uniforms (left: catalogue #1994.0556.1 & right: 1994.0557.1) have Newfoundland shoulder insignia. Newfoundland was a British colony until 1949.

Display large image of Figure 9

48 At the beginning of the Second World War, temporary modified RAF badges were issued to Canadian flyers. These were almost identical to the RAF pattern except that an embroidered “C” was superimposed over the “RAF” in the central circular field of the Pilot’s badge (see the uniform at right in Fig. 2). RCAF personnel demanded distinctive qualification badges, so in 1943 official Canadian air crew issues began to appear. These included an embroidered “RCAF” in line on the Pilot’s badge (see Fig. 14). The same monogram appeared in smaller letters on all other flying badges (Fig. 7).57

RCAF Women’s Division

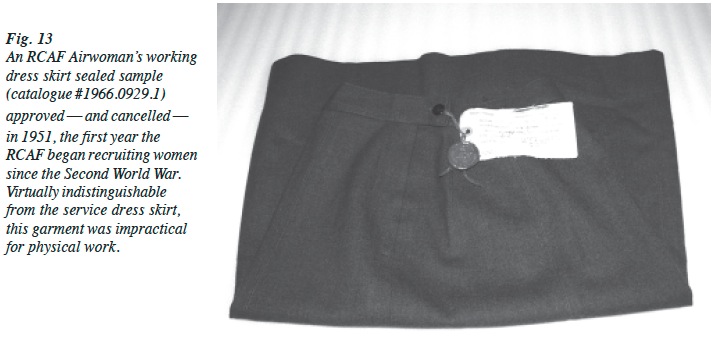

49 The Canadian government formed the Canadian Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (CWAAF) in 1941 to recruit women for ground trades. The organization, later renamed the RCAF Women’s Division, was disbanded at the end of the Second World War. In 1951 the RCAF again began to recruit women for all duties except flying and combat roles, but there was no longer a separate women’s division. Early female members of the technical trades complained of work dress slacks and skirts that, when they did arrive, were slow to be issued, available in insufficient quantities and poorly designed for physical work. Some simply borrowed men’s uniform items until more suitable clothing became available (see Fig. 13).58 The number of occupations and trades open to female personnel increased dramatically in the 1970s.

50 Based on the male uniform pattern, female uniforms were modified to suit the female form; skirts or slacks were substituted for trousers, and distinctively feminine items such as purses and maternity clothes were added. Female-specific foot-wear, neck ties and especially head dress have been adapted from contemporary fashion. Female equivalents to the familiar male air force peaked general service cap, for example, have included variations with broad brims, a pleated (or pinched crown, or one modelled on the French kepi. Most contemporary female service caps are a rounded “bowler” design with the brim turned up at the sides and back. Field service (wedge) caps are worn by both genders, although early styles worn in the RCAF resembled those worn by commercial airline stewardesses at the time (see Fig. 17).

Royal Canadian Air Cadets (RCAC)

51 The Air Cadet League of Canada was formed in 1941 as a civilian volunteer organization to train young men for war service in the RAF and RCAF. Its name was changed to the Royal Canadian Air Cadets in 1946. Closely associated with its professional counterpart, the organization continues to train young people from the ages of fourteen to eighteen in aviation, citizenship and leadership.59

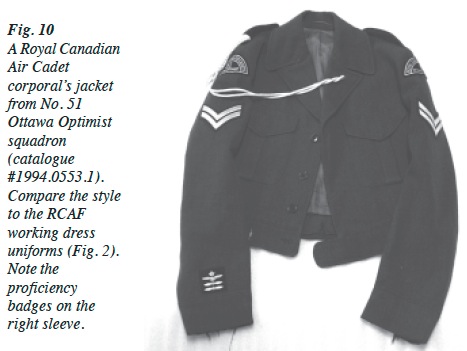

52 The RCAC uses a simplified version of the regular air force dress regulations. The single uniform consists of a jacket and trousers that are similar in style to the regular air force working dress uniform, worn in a number of combinations with a field service cap and ankle boots. White belts, lanyards, gaiters and cotton gloves are worn for ceremonial occasions. In the pre-unification period, Air Cadets wore a blue-grey uniform virtually identical in colour and style to the RCAF working dress uniform (see Fig. 10). Between 1968 and 1985 they wore a green uniform that mirrored the working dress worn by the Canadian Forces (air operations). The contemporary Air Cadet uniform is similar to the Canadian Forces (air force) sky blue base dress uniform and includes a number of light blue shirts and accoutrements.60

Fig. 10 A Royal Canadian Air Cadet corporal’s jacket from No. 51 Ottawa Optimist squadron (catalogue #1994.0553.1). Compare the style to the RCAF working dress uniforms (Fig. 2). Note the proficiency badges on the right sleeve.Royal Air Force Ferry Command (RAFFC)

53 In 1940 the British government encouraged Canadian Pacific Airlines to create the Canadian Pacific Atlantic Ferry Organization to ferry aircraft from manufacturing plants in the United States to Canada—to Gander, Newfoundland or Goose Bay, Labrador—and across the Atlantic to England. Air crew consisted of British, American and Canadian civilian commercial pilots and radio operators. In 1941 the service was militarized, designated RAF Ferry Command and began to use air crew trained in the BCATP. Due to growth in the size and importance of the organization, Ferry Command was absorbed into RAF Transport Command as No. 45 Transport Group in 1943. Its role continued to expand worldwide until the end of the war in 1945, transporting aircraft to destinations as far away as Australia.61

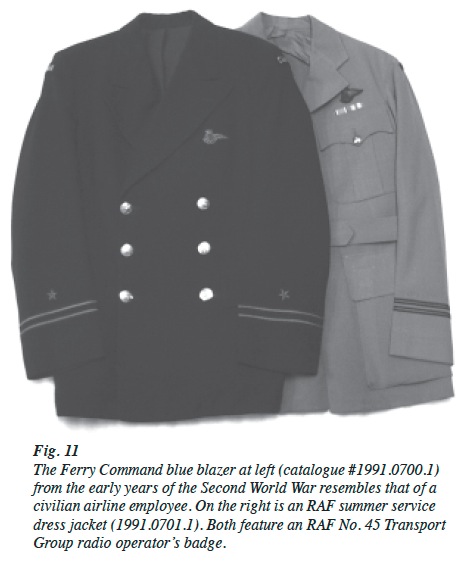

54 Before it became part of the RAF, Ferry Command air crew were issued uniforms similar to those worn by commercial airline personnel, so that if they were shot down and captured they would be less likely to be shot as spies. It appears, however, that their clothing often included a flamboyant mixture of official uniform issue and civilian clothing. No doubt dress regulations were more strictly enforced when Ferry Command was absorbed into the RAF, but many of the air crew remained civilian. Between 1941 and 1943, RAFFC air crew wore RAF service dress and work dress uniforms issued by the BCATP and after 1943 they wore standard RAF pattern uniforms with distinctive No. 45 Transport Group badges62 (see Fig. 11).

Fig. 11 The Ferry Command blue blazer at left (catalogue #1991.0700.1) from the early years of the Second World War resembles that of a civilian airline employee. On the right is an RAF summer service dress jacket (1991.0701.1). Both feature an RAF No. 45 Transport Group radio operator’s badge.Royal Canadian Navy: Naval Aviation Branch

55 Following the creation of the Royal Canadian Navy in 1910, many Canadian naval pilots served in Britain’s Royal Navy and RNAS.63 When the RCAF was formed in 1924, it provided flight training to Canadian naval personnel. Early in the Second World War, the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) sought to recreate a version of the RCNAS from the First World War (see above) to conduct anti-submarine warfare and protect convoys crossing the Atlantic. The RCAF opposed the suggestion, since the shore-based aircraft of its Maritime Command patrol squadrons were already providing air cover for the fleet in cooperation with the navy. Senior naval planners argued that it was more effective for airplanes to operate from escort carriers that could accompany the convoy or fleet, and that single control by one service was more efficient than inter-service coordination. The Canadian government decided to maintain the status quo for the duration of the war due to fears that maintaining two air forces would lead to duplication of command and support services, and would be a drain on resources.

56 After the war a compromise was reached that copied the British arrangement:64 the RCN created its own Aviation Branch for carrier operations, but left maritime air operations to the RCAF.65

57 During the Second World War, many RCN and Royal Canadian Navy Volunteer Reserve (RCNVR) officers served in the Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm, which in 1943 formed four Canadian squadrons. The RCN also maintained several light fleet (escort) aircraft carriers (sailors were mostly Canadian but air crew were almost exclusively Royal Navy personnel).66 At the end of the Second World War, the RCN was the third-largest navy in the world, but it was not a balanced naval force capable of operating independently. It did not have a distinct flying service until the formation of the Naval Aviation Branch in 1946, which operated a fleet of carrier-based airplanes and helicopters, specializing in antisubmarine warfare. The Naval Aviation Branch operated in this capacity until it was absorbed in 1968 into the CF (air operations) Maritime Air Group in the unification of the Canadian Forces. In 1970, Canada’s last aircraft carrier, the HMCS Bonaventure, was decommissioned.67

58 Uniforms and insignia worn by the Royal Canadian Navy during this period were virtually identical to their Royal Navy counterparts, which is not surprising since the RCN Naval Aviation Branch considered the RN Fleet Air Arm its parent organization (in much the same way the RCAF was the descendant of the RAF). The most visible difference is the “CANADA” in raised lettering on the buttons and in embroidered fabric thread on the shoulder insignia. The blue dress uniform’s most distinctive component was a double-breasted open collar blazer with gold braid. By this time the tradition was well established in Commonwealth naval aviation services that flying qualification badges, featuring a metal anchor in a central field between outstretched wings, were worn on the left sleeve above the rank braid rather than the breast of the jacket. Navy uniforms have managed to retain remnants of the full dress uniforms that preceded them: the double row of buttons on the blue dress blazer and the standup collar on the white dress tunic68 (see Fig. 12).

Fig. 12 Royal Canadian Navy pilot’s uniform jackets. Left to right: khaki summer service dress with looped naval rank braid on the shoulder boards (catalogue #1992.2223.1); navy white dress with a stand-up collar (1992.2225.1) and navy blue dress blazer with a pilot’s badge on the sleeve (1992.2224.1).Fig. 13 An RCAF Airwoman’s working dress skirt sealed sample (catalogue #1966.0929.1) approved — and cancelled — in 1951, the first year the RCAF began recruiting women since the Second World War. Virtually indistinguishable from the service dress skirt, this garment was impractical for physical work.Canadian Army Aviation

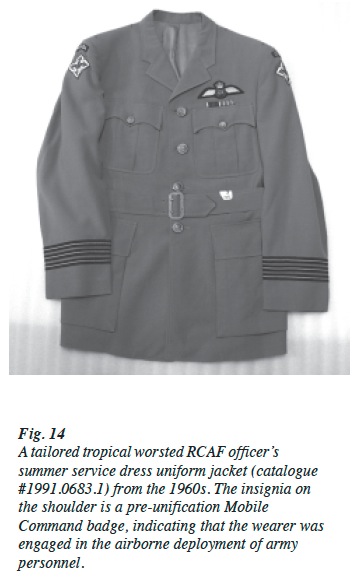

59 As seen above, the Royal Canadian Navy followed the example of its British and American counterparts in forming its own air arm in 1946, effectively creating a specialized air force within the naval service. By contrast, Canadian Army aviation has remained relatively modest in scale.69 The Canadian approach has been inter-service cooperation, with RCAF crews assigned to facilitate troop deployment and provide tactical support for army operations (see Fig. 14 for a pre-unification air force uniform jacket bearing Mobile Command badges). The transition from aerial army support to active tactical participation in land battles likely took place during the Battle of El Alemain in North Africa in 1942.70 The Canadian Army has also maintained its own small fleet of helicopters and small airplanes, used mainly for aerial observation, personnel and materiel transport and search and rescue. Beginning in the 1940s, the RCAF provided air crew training for army pilots.71

Fig. 14 A tailored tropical worsted RCAF officer’s summer service dress uniform jacket (catalogue #1991.0683.1) from the 1960s. The insignia on the shoulder is a pre-unification Mobile Command badge, indicating that the wearer was engaged in the airborne deployment of army personnel.

Display large image of Figure 14

60 Canadian Army service dress uniforms have traditionally been very similar to those of the air force, but brown instead of blue. A khaki drill uniform, similar to air force summer service dress uniform, was worn before and during the Second World War. The battle dress uniform was also introduced during the Second World War and worn until the late 1960s. Again, apart from the brown or copper-green colour, its pattern was very similar to the air force working dress uniform. A green bush dress uniform replaced the khaki drill uniform for summer dress between 1946 and 1968. Until the Canadian Forces unification in 1968, army pilots wore standard army uniforms with a distinctive flying badge on the left breast of the jacket featuring a lion atop a crown between outstretched wings. This badge is almost identical to the one worn by pilots in the British Army Air Corps.72

Canadian Forces (Air Operations/Air Command)

61 Canada was among the first countries to integrate its army, navy and air force into a single department (Department of National Defence) in 1923 to reduce costs and inter-service rivalry. However, the three service branches continued to operate semi-independently within DND.73 The purpose for taking integration of the Canadian armed forces to the next level in 1968—unification—was to further eliminate competition for resources and duplication of effort among the three traditional service branches (and between the Chiefs of Staff and the civilian DND). The government hoped the money saved could be used to purchase capital equipment to outfit a small, modern, field-effective, well-equipped, fully integrated force capable of rapid deployment.

62 The former Canadian army, navy and air force were designated Canadian Forces: Land Operations, Sea Operations and Air Operations respectively. Army and naval air elements were integrated with former RCAF air elements under Air Operations,74 and divided among CF operational commands. Some former RCAF and army aviators became part of Mobile command, while the remaining former RCAF and navy flyers were assigned to Maritime Command. This arrangement kept land and sea forces intact while parcelling out former air force elements among them, effectively reabsorbing the air force back into the army and navy. The lack of centralized command for air elements was later found to be unworkable, so in 1975 they were again centralized as operational groups under CF Air Command, in effect recreating the air force.75

63 The new common Canadian Forces uniforms were intended to reflect a break with the British martial tradition and to redirect loyalty away from the traditional service branches toward a more efficient unified command structure. Unification also imposed a common ranking system—that of the army—on the entire CF organization (e.g., an air force Squadron Leader or navy Lieutenant Commander now assumed the army rank of Major), but used navy-type sleeve braid rank insignia on officers’ uniforms.76

64 A number of reasons have been suggested to explain the selection of the green “unification” Canadian Forces uniform:

65 Less British and less Imperial: Historian and author Jack Granatstein suggests that the step from integration to unification of the Canadian armed forces in 1968, developed from Lester Pearson’s experience in the 1956 Suez Crisis. Canadian peacekeepers were initially at a disadvantage because their red ensign and British-pattern battledress uniforms were equated with Great Britain, one of the perceived aggressors.77 When Pearson later became Prime Minister of Canada, he was instrumental in adopting a distinctive new Canadian flag. Even more important, for our purpose, he lent his support to Defence Minister Paul Hellyer in the adoption of distinctive new military uniforms. Both measures were designed to minimize Canada’s British connections, which were seen as a liability for Canadian peacekeepers in the third world, where Britain was often identified with imperialism.78

66 Less British and more Canadian: As noted above, armed forces are often seen as an outward expression of national will and character. Canadian Forces unification was introduced the year after Canada’s Centennial in 1967. The late 1960s was a time when Canada was increasingly confident and seeking to redefine itself and assert a unique identity that was neither British nor American. It also coincided with a period in which the Canadian government was reducing its international commitments to focus on domestic policy and developing new social programs. In adopting a more distinctly Canadian military uniform, the Canadian government was perhaps hoping to reflect the new realities of a unique, independent, bilingual and multicultural nation.

67 Less military and more “constabulary” Some observers felt that the new design looked more like a police officer’s than a soldier’s uniform. Central to Canada’s role in international affairs in the late 1960s was participation in UN peacekeeping, internal security and protecting Canadian sovereignty. Given that in the Vietnam era many Canadian liberal political thinkers equated the “military with militarism,”79 it is likely that the new uniforms were intended to reflect the less military and more “constabulary” role envisioned for the Canadian Forces. Significantly, the word “Armed” was dropped so as to refer to the Canadian Forces, as opposed to Canadian Armed Forces.

68 Less British and more American: Given that the new Canadian forces uniforms followed the army model, it is striking how they contrasted with their predecessors, which had resembled the brown and khaki uniforms worn in the British Army. Many observers felt that they looked “American” since dark green is the colour traditionally preferred by the U.S. Army. Since the Second World War, the RCAF had placed less emphasis on the need for Imperial cohesiveness (which had dominated its thinking throughout two world wars) in favour of more cooperation with the USAF in continental defence against Soviet aggression through NORAD. Interestingly, dress regulations for the unification period introduced the American rank “brigadier-general” to replace the traditional British “brigadier.”

69 Army pattern and ranks: The new green uniforms and ranking system were based on the army model, which likely reflected the traditional view of Canadian military planners that the army was the oldest and most “senior” Canadian service branch. The Canadian militia tradition was established long before Confederation in 1867, whereas the Canadian navy and air force were not formed until the early 20th century. Clearly, the perceived future role of the Canadian forces in peacekeeping and quick armed intervention in small wars, necessitated that the army be the central player with the navy and air force in supporting roles.

70 The new service dress uniform consisted of a rifle (dark) green80 jacket (see Fig. 15) with gilt buttons, gold sleeve rank braid, predominately gold and red badges and insignia, rifle green trousers and tie and a linden (light) green shirt (see Fig. 15). General officers wore traditional army rank insignia on the shoulder straps, retaining the crown and crossed swords, but replacing the stars with red maple leafs. A red maple leaf also replaced the previous service-specific emblems on pilot’s badges. The new work dress uniform included a zippered “windbreaker” jacket and could be worn with a wedge or beret style field service cap.81

Fig. 15 Despite the pre-unification RCAF pilot’s badge, this rifle green Canadian Forces service dress uniform jacket (catalogue #1993.0408.1) could not have been worn before 1968. A small act of resistence against unification by this Second World War veteran?

Display large image of Figure 15

Canadian Forces (Air Force)

71 In the 1970s, the Liberal government of Pierre Trudeau reduced defence spending and NATO commitments in favour of UN peacekeeping and increased spending on domestic programs. Consequently most of the hoped-for capital equipment (including airplanes) was not purchased. While the administrative and financial advantages of integration could not be dismissed, it came to be recognized that operational efficiency and morale had been compromised by undermining the esprit de corps of the traditional service branches.82 Following increased Soviet activity in Afghanistan and the election of a Conservative government in Canada in 1984, Prime Minister Brian Mulroney adopted the recommendations of then Defence Minister Perrin Beatty’s second White Paper on Defence, to revitalize the Canadian armed forces for participation in United States President Ronald Reagan’s Cold War initiatives. In 1989 the Soviet Union collapsed unexpectedly and the Cold War ended. The Canadian armed forces were further reduced in size and the NATO air division was withdrawn from Germany. Since then the focus of Canada’s forces has been on UN peacekeeping, protecting Canadian sovereignty, homeland defense, armed intervention as part of U.S.-led coalitions, maintaining domestic order, disaster response and fighting terrorism.83

72 Unification involved much more than a mere change of uniforms,84 but the uniform was its most visible manifestation (and perhaps a reminder of the insensitivity with which it was imposed), so it became the focus for those who resented the break with the old loyalties and traditions. To restore efficiency and morale, the Second White Paper on Defence called for a return to the terms Army, Navy and Air Force. Between 1984 and 1987 the Canadian government reintroduced new uniforms, badges and accoutrements that were distinctly Canadian, distinctly military, unique for each of the three service branches and represented a return to the traditional style of dress for the navy and air force.85

73 The Canadian Forces (Army) retained the unification rifle green uniform as a winter service dress, but added a tan summer service dress uniform, reminiscent of the old Canadian Army and RCAF khaki service dress. This uniform has since been discontinued. The Canadian Forces (Navy) reverted to close variations of its pre-unification blue and white dress. The Canadian Forces (Air Force) adopted heavy and light-weight versions of a sky blue service dress uniform, not unlike the colour of the RAF uniform made from Russian cloth introduced in 1918, for seasonal wear (see Fig. 16). The navy and air force also reverted to their traditional pre-unification ranking systems, so a General could again be addressed by the pre-unification rank of Air Marshal or Admiral if a member of the CF (Air Force) or CF (Navy) respectively. The category of uniform previously referred to as working dress was now called base or garrison dress. It followed the same general design as the unification period working dress, but returned to more traditional colours: black (midnight blue) for the navy; tan or camouflage pattern green for the army and sky blue for the air force.86

Conclusions

Canadian national identity

74 As discussed in some detail above, the CAF and RCNAS blue-black uniforms, the CF green uniforms and the distinctive Canadian 1943 pattern RCAF qualification badges can be interpreted as attempts to put a uniquely Canadian face on our armed services—the air services in particular. By contrast, the uniforms worn by the RCAF throughout its history were clearly intended to be as British as possible and reinforce Canada’s identity as a member of the Commonwealth. When examined in their historical context, these uniforms say a great deal about Canada’s evolving national self-image.

Distinct air service

75 The traditional RAF and RCAF winter and summer service dress uniforms symbolize the origins of the air force in supporting roles as part of the British Army and Royal Navy. Larry Milberry, general editor of Sixty Years: The RCAF and CF Air Command 1924-1984, argues that by patterning themselves closely after the RAF, the RCAF and other Commonwealth air services ensured their survival as independent branches, since the RAF was the first and most independently-minded separate military air service, and successfully resisted being re-absorbed back into the army and navy.87 The concept of strategic bombing was based on the premise that future wars would be fought from the air, with armies and navies relegated to supporting roles.88 Distinctive blue uniforms asserted the independence (or even preeminence) of the air force. Canadian Forces green unification uniforms were used to symbolically as well as literally re-absorb air operations back into the army and navy, while a return to traditional uniforms asserted the re-emergence of Canada’s air force as a distinct service branch.

Socio-economic status89

76 At the beginning of the 20th century there was a conspicuous distinction between the uniforms worn by officers and enlisted personnel. The introduction of the service dress jacket during the First World War allowed gentlemen to enter social venues that required patrons to wear neckties, thus excluding “other ranks” who still wore high collar undress jackets as a “walking out” uniform. By the Second World War, all ranks could wear service dress, although not all were issued them. A similar progression allowed first officers, and only later other ranks, to modify their work dress jackets to accommodate a necktie late in the Second World War. While service dress was issued to enlisted personnel in the post-war period, officers could continue to have theirs tailor-made of barathea fabric, while the standard issue for enlisted personnel was made from rough serge until the early 1950s. From the beginning of unification in 1968 to the present, all service dress uniforms worn by both officers and enlisted personnel in the Canadian Forces are standard issue only. As a final social leveller, mess dress can now be purchased, although it is not mandatory, by enlisted personnel as well as officers. Armed services always reflect the society that creates them, and the gradual minimizing of pronounced differences between officers and enlisted personnel uniforms mirrors the democratization of society as a whole.

Gender

77 The 20th century saw the development of aviation and air power. It coincided with a period that is historically significant because of the changing social roles for women in western society. Women’s military uniforms, including air force uniforms, have generally reflected styles drawn from popular fashion in the context of the broader culture, and have evolved as the roles of women in the military have expanded.

The future of Canadian military aviation

78 Military strategists have recognized since the First World War that the service branches work best when they work together. Armies need navies to secure landings and transport troops, navies need armies to protect their bases and both need aircraft to secure air cover and gather intelligence. Air power remains essential for victory in any land or sea battle, but the experience of the Americans— from Vietnam in the 1960s to Operation Desert Storm in 2003—shows that overwhelming air superiority alone is not a substitute for “boots on the ground.” The realities of international conflict at the beginning of the 21st century highlight the importance of Canada maintaining a small, well-equipped and highly mobile armed force, capable of operating independently or as part of coalitions for rapid deployment. Recent world events also confirm that such concepts as diplomatic influence, peacekeeping and national sovereignty are meaningless unless Canada is respected and seen as capable of defending itself and willing to participate in armed intervention when our values are threatened.90 Canada has been a leader in the development of air power in the 20th century. Our military aviation history shows that pride in the three distinct services contributes positively to morale. But air elements must be fully integrated operationally with land and sea elements, and unified administratively under a single command for maximum effect.91 The air force uniform is far more than mere clothing: it is a visible symbol that communicates loyalty to country, respect for tradition and pride in the air force as distinct service.

Notes