Research Reports / Rapports de recherche

Paintbox at Sea:

The Materials and Techniques of Canadian Second World War Artist C. Anthony Law

1 The material history of an artist’s work can enrich our appreciation of an artist’s oeuvre and painting methods. Art historians preoccupy themselves mostly with the intellectual relationship of the various steps involved in the creation of an image from quick to finished sketches to larger more finished works. Art historical research into artists’ papers and archives can reveal seemingly unimportant information about the artist’s practice and materials and this information is too often overlooked and undervalued. Conservation research has the capacity to add another dimension to the full understanding and interpretation of a work through examination and scientific analysis that constitutes its material history. Such research can clarify difficult issues relating to dating, authenticate problematic works, and identify significant changes in the artist’s working methods. By combining these two areas of art historical and conservation research we have the unique opportunity to better understand the significance of the material history of a work in relation to its intellectual significance. The case of Anthony C. Law (1916–1996) is most revealing.

2 Anthony C. Law was born in London, England, in 1916 to Canadian parents who were, at the time, posted in the United Kingdom. Law eventually moved back to Canada with his parents and spent some time in Ottawa where he had the opportunity to view paintings at the National Gallery of Canada. Apart from his mother encouraging him to fulfil his artistic desires at an early age, he was also greatly influenced by Canadian anthropologist Dr Marius Barbeau who first introduced him to oil paintings by the Group of Seven. His encounter with this Group would later have a profound impact on his materials and style. Law had the opportunity to study under Franklin Brownell RCA, OSA, Frank Hennessey RCA, OSA, and Fred Varley RCA, OSA, while studying drawing and painting at the Art Association of Ottawa. Fred Varley taught Law how to apply colour by building up the layers and also instructed him in portrait painting and life drawing.1

3 In 1936, Law returned to Quebec City and studied with Percyval Tudor–Hart. He had his first exhibition in 1937 in Quebec City. By all accounts the fifty canvases Law exhibited established him as a talented young artist who did not shy away from strong colours.2 His artistic vision of Canada’s landscape resulted in a number of prizes for his works such as the Montreal Art Association’s Jessie Dow Prize in 1939 and again in 1951.3 By the outbreak of the Second World War, Law was an accomplished artist who was determined to serve his country by joining the navy and to continue painting in unfamiliar territory. He intended to visually record his experiences aboard motor torpedo boats in North Atlantic waters and leave a legacy of these events to future generations through his paintings and drawings. He was first appointed an official war artist in 1943 and official naval war artist in 1945.

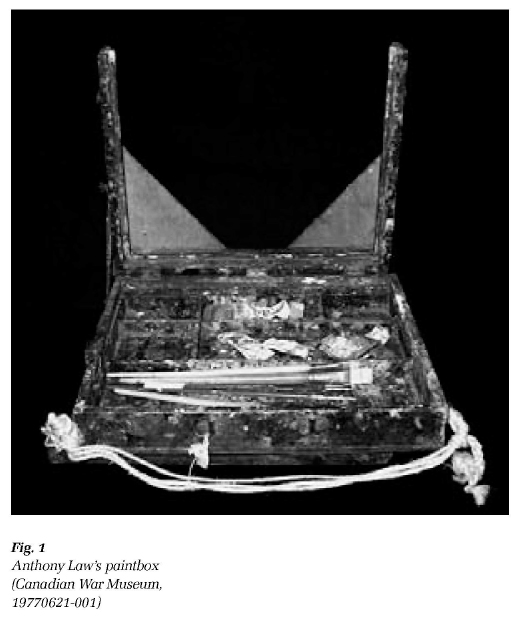

4 Throughout the war years, Law had his sketchbook, art materials and paintbox at his side. This paintbox is now in the permanent collection of the Canadian War Museum and is an important artifact in relation to Law. It bears the scars of battle in terms of poor condition but provides a significant amount of historical data on Law’s working methods and materials. In addition to the paintbox, the Canadian War Museum also has numerous small paintings on wood panel of his, which are considered working sketches for his larger canvas paintings. Many of these small sketches correspond to the usage dates of the paintbox and were likely produced in the easel section of his paintbox. To find both Law’s paintbox and sketches at one institution allowed for a detailed comparative analysis of components found on both to be undertaken.

The Paintbox

5 Law purchased his paintbox in Quebec City in 1938 and took it overseas in 1940 and used it until 19494 (Fig. 1). In a letter dated 15 November 1977 to the Canadian War Museum Law writes:

Clearly the paintbox was indeed an important item in Law’s life, he writes about it with passion, regarding it not only as a tool to achieve his artistic vision, but also as a travelling companion during his naval service. He eventually gave this war-weary paintbox to a student but the student returned it to him so that it could be donated to the Canadian War Museum in 1977.6

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2Structure and Function

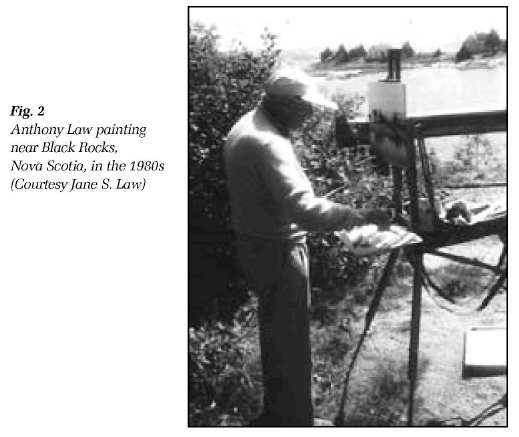

6 The paintbox is a combined sketch box and slotted easel with telescopic legs. The multi-functional aspect of this paintbox design allowed Law to quickly record events of action at sea. It is portable and can be used for both indoor and outdoor work. This seems to be Law’s preferred style of paintbox, since this style is seen in many photographs of Law painting outdoors. Law followed the traditional "plein air" style of painting pursued by the Group of Seven (Fig. 2).

7 The paintbox measures 44 cm wide, 36 cm deep and 6 cm high. It is constructed primarily of wood and metal, with a replacement handle made of jute. The top face of the cover is missing, including the front panel, which would have latched to the base of the box. The two triangular shaped wooden sections found at each bottom corner of the lid appear to be more recent additions. There is a metal plaque along the left side of the box, which is riveted to the box and has relief printing that states: OTHER WAY; CHICAGO; KEEP COVER ON BOX. The top lid, which now consists of only the easel frame and triangular wooden sections, is hinged and functions as an expandable easel, which can hold up to four panels measuring approximately 33 cm high, 39 cm wide and 6 mm deep. If the easel is expanded it can hold panels up to 66 cm wide.

8 The interior of the box consists of six crimped metal storage compartments to hold paints and tools and there is a ledge above the storage compartment to hold the palette. The palette is secured onto this ledge by slipping it face up under three small metal clips at the back of the box and moving two rotating clips over the front of the palette. The secured palette has sufficient clearance in the paintbox to avoid contact of any material with wet paint on the palette.

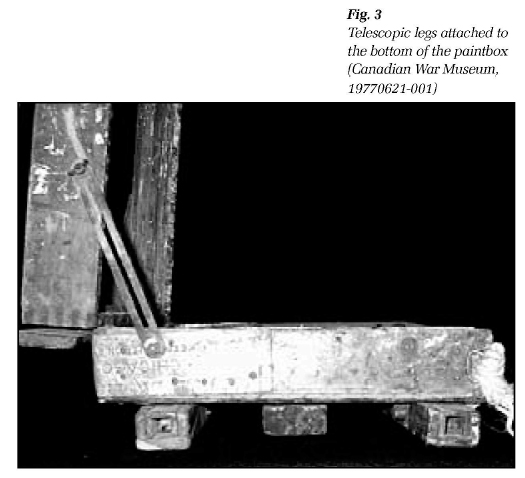

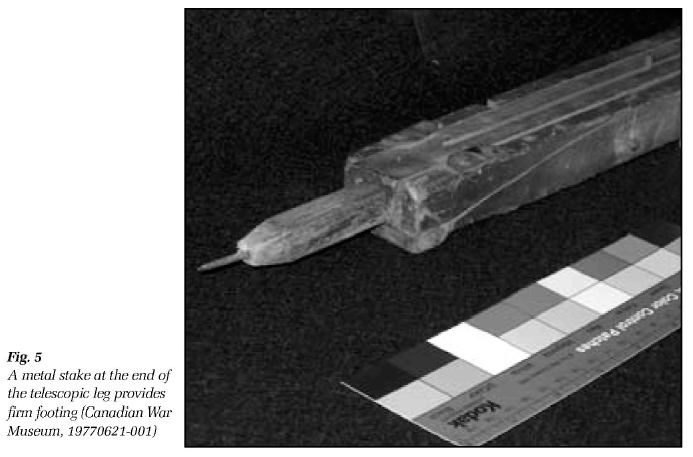

9 The bottom of the box holds three folding telescopic legs that can be extended and tightened when required and secured onto the bottom of the box with metal clips when not in use (Fig. 3). When extended to their full length, these telescopic legs support the paintbox to a height of approximately 94 cm and allow the artist to work in a comfortable standing position (Fig. 4). The legs also have metal stakes at the end of each leg, which can be used to firmly plant the legs in the ground (Fig. 5).

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3 Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4Contents

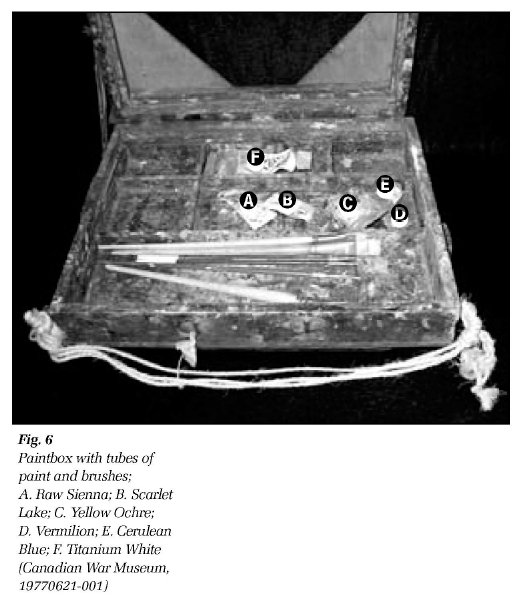

10 The paintbox was not with Law, since he replaced it, until shortly before it was shipped to the Canadian War Museum but Law presumably placed some of his old tubes of oil paint and brushes in the box to make it as authentic as possible. He also made an effort to locate the original palette but states in a letter to the Canadian War Museum that it was destroyed.7 The contents of the paintbox include oil paints, brushes and a palette as follows (Fig. 6):

- Raw Sienna (M. Grumbacher, New York)

- Scarlet Lake (M. Grumbacher Inc., New York; on verso: Toronto, Canada)

- Yellow Ochre (Winsor & Newton)

- Vermilion (Winsor & Newton)

- Cerulean Blue (Golden Palette, M. Grumbacher, Toronto)

- Titanium White (Talens Oil Colour, Made in Holland)

(front to back of compartment)

- 1. bristle brush 1/2"

- 2. bristle brush 1/8"

- 3. bristle brush 1/8"; M. GRUMBACHER GAINSBOROUGH Series 1271B

- 4. bristle brush 7/8"

- 5. bristle brush 1/8"; 1…SERIES 1271B

- 6. bristle brush 1/2"; WILTON; WINSOR & NEWTON LTD; MADE IN ENGLAND

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5 Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 6 Display large image of Figure 7

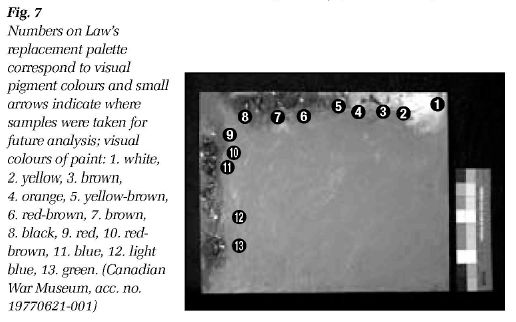

Display large image of Figure 711 The original palette, which Law used with this box, was lost and has been replaced (Fig. 7). Law states: "Unfortunately, the palette was destroyed and I have made a new one for the box. In addition, I put the colours I use in my usual arrangement."8

12 The replacement palette is made of rough, three-ply wood and measures 33 cm by 41 cm and is 6 mm thick. The oil colours found on the replacement palette indicate a series of warm hues along the top, horizontal side of the palette (includ ing white to the far right of the row and black to the far left) and cooler hues along the left, vertical side of the palette. From earliest times, when painting techniques were passed on from master to apprentice, they were conveyed in an orderly manner. Apprentices were taught to "set the palette" or arrange the colours in a particular sequence on the palette. This methodology was kept secret within artists’ guilds and few manuscripts were widely available on painting technique. As published information on painting technique became more widespread and artists travelled and shared information, we find precise references to the preparation of the palette. One early published and illustrated account of "setting the palette" can be found in the De Mayerne Manuscript of 1620. It states that the lightest colours should be placed along the top and darker colours lower down on the palette.9 It is likely that Law was trained in such a traditional method of preparing a palette since there is a systematic and conscious application of colours on his palette. In consulting three colour photographs of the artist painting outdoors, this same colour arrangement is clearly visible on each palette and, additionally, he attached a small metal cup along the upper left edge of the palette, presumably to hold solvent. Law also put down a thin, grey, neutral tone scumble in the centre of his palette, which was allowed to fully dry. More accurate colour mixing is achieved on top of this layer. Tube applications of oil colours were placed along the top and left side of the palette.

Materials and Techniques of Painting

Panel Paintings

13 Law produced his finished paintings on canvas by first sketching on a small wood panel, producing the sketch "on the spot."10 These images would later be "copied" on a larger scale to canvas. Usually these small panels fit into the easel component of his paintbox lid. Of the fifty panels examined at the Canadian War Museum, all were on wood panel except for one, which was on artists’ board and not included in this study. Of the remaining panels, one wood panel was too wide to fit in the easel and two wood panels were too small to be securely held in the paintbox easel and these works were also eliminated from this study. A total of forty-six panels were included in this study. Although some of the panels are undated, the majority were painted between 1943 and 1945, therefore conforming to the dates that the artist would have been using the paintbox.

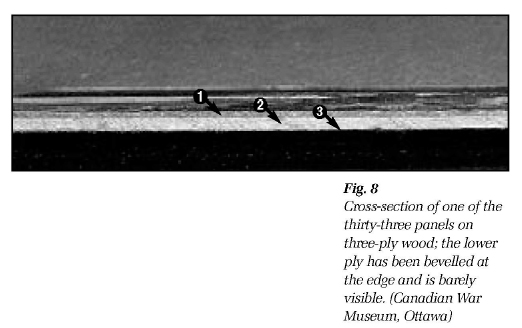

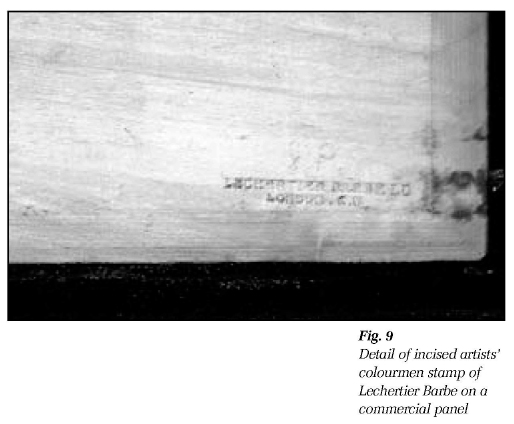

14 Of the forty-six wood panels examined during this research, which would fit securely into the paint box easel, three were on solid wood panel, ten were on commercially manufactured panels and the remaining thirty-three panels were made of three-ply wood (Fig. 8). The majority of the panels (thirty-seven) were dated between the years 1943–1945 and nine panels were undated. All ten commercial panels measure 33 cm high and 46 cm wide and bear the incised stamp mark of the London artists’ colourmen firm of Lechertier Barbe on the back of each panel. Some of the panels also have "8 p." written by hand above the stamp and this likely refers to the cost of the panel (Fig. 9). It is interesting to note that Law painted all ten of these commercial panels in 1943. This is the year that Law was in London working as an official war artist and he could easily have purchased these panels himself at Lechertier Barbe. The artists’ colourmen firm of Lechertier Barbe still exists today and it is interesting to note it was also the supplier of artists’ materials to Winston Churchill.11

15 Law preferred to work on wood panel for his sketches and states that he worked like "the old Group of Seven."12 He stated that a wood panel had such a beautiful colour so that when it was painted on outside "you don’t get the terrible glare of light" (as you would from a white surface, for example).13 To prepare his panels for painting, Law first rubbed them with linseed oil and then let them dry. He stated that he had to work quickly because he was so pressed for time while on board his ship.14 The logistics of painting on board a moving ship, in all weather conditions, must have certainly been a challenge for Law. These spontaneous sketches were executed directly on the panel with no evidence of a ground preparation and the raw panel can sometimes be seen beneath his brushstrokes. His method of painting consisted of first applying dark colours to the panel and then lighter colours.15 The paint was applied hastily and in some cases, a palette knife was used to add texture to the work. After completing the sketches, he took them back to his studio to work them into larger canvases.16

Use of the Paintbox

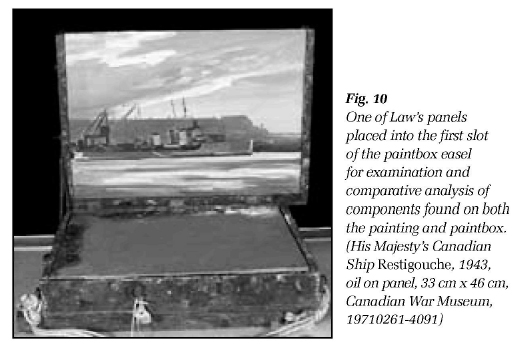

16 In order to establish a physical link between the use of the paintbox and production of the Canadian War Museum’s panels, a comparative analysis of components found both on the panels and paintbox was undertaken. Each of the forty-six panels was systematically placed into each of the four slots of the paintbox easel and the width of the easel was adjusted for each panel (Fig. 10). Of particular interest during this stage of the examination was the unique buildup of paint deposits along the inner edges of the four slots in the easel. The hypothesis was made that this unique pattern of paint buildup could be matched to brush mark patterns and paint ridges found on the front of Law’s panels. If the pattern of paint buildup on the easel and brush mark patterns and ridges on the panel matched, it would confirm that the panel had been painted in the easel component of this paintbox.

Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 8 Display large image of Figure 9

Display large image of Figure 9 Display large image of Figure 10

Display large image of Figure 10 Display large image of Figure 11

Display large image of Figure 11 Display large image of Figure 12

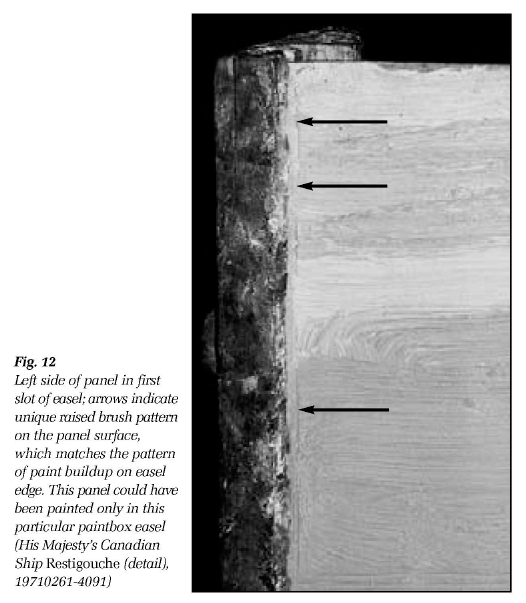

Display large image of Figure 1217 In preparation for painting, Law would slide his linseed oil prepared panel into one of the four available slots in the easel component of his paint box. If required, he would adjust the width of the easel by extending the right, movable part of the easel (Fig. 10). The edges of the inserted panel were covered by the edge of the slot by approximately 6 mm. As Law painted, his brush would occasionally hit the inner edges of the easel’s frame, depositing a small amount of oil paint in this area. As time went by, these deposits formed a unique pattern of paint along the vertical sides and bottom edge of each of the four slots (Fig. 11). The panel shown in Figures 10, 11 and 12 was positively identified as having been painted in the first slot of the easel (slot closest to artist) by matching up the unique pattern of paint deposited on the edge of the easel and a series of brush mark ridges found on the panel (Fig. 12). The arrows in Figure 12 clearly show where the patterns of paint deposits on the edge of the easel and brush mark ridges on the painted panel are identical.

18 General observations made during this comparative analysis included finding visible ridges of paint on the surface of some panels that correspond to the pattern of ridges found on the easel; visual identification of specific colours found in the same location on both panel and easel; visible brush marks on panels that ended at the easel’s edge or deviated around paint deposits on the easel; and, smudged grooves in the paint that indicate that the panel was removed from the easel while still wet. The systematic examination of forty-six wood panels resulted in the positive identification of twenty-two panels where there was sufficient comparative visual evidence to conclude that they had indeed been produced in the easel of the paintbox. Fifteen were very likely produced in the easel and the remaining nine panels examined during this study were probably produced in the easel based on the testimony of Law in relation to when he used the paintbox and the dates in which the panels were produced.17

Conclusions

19 First and foremost this study provides intimate information about the artist’s materials and his specific working methods. We have clearer information on how he produced his quick sketches, often at sea using his paintbox. The study of his replacement palette and preferred colours bring to life a clarity, often forgotten or obscured, of his experience as a practising artist. We accept that some materials found in the paintbox may not be contemporary to the creation of the associated panels because the box had been out of Law’s hands for some time before it came into the collection of the Canadian War Museum. Fortunately, there was still sufficient original material evidence on the easel component of the paintbox to allow comparative work to the undertaken in order to definitively match many of Law’s sketches to the use of the paintbox. By bringing Law’s sketches and paintbox together we are reconstituting the site of Law’s orderly artistic practice. It is like entering the private studio of the artist, which remains a personal and intimate experience.

The author would like to thank Laura Brandon, Curator, Canadian War Museum and Gilbert Gignac, Library and Archives Canada, for their advice and valuable suggestions to this manuscript. Thanks are also extended to Helen Holt, Canadian War Museum, for allowing access to the paintbox and paint sampling and to Alison Murray, Queen’s University, for her generous scientific advice. Finally, I would like to thank Mrs Jane S. Law for sharing information about her husband’s life and for providing photographs.