Research Reports / Rapports de recherche

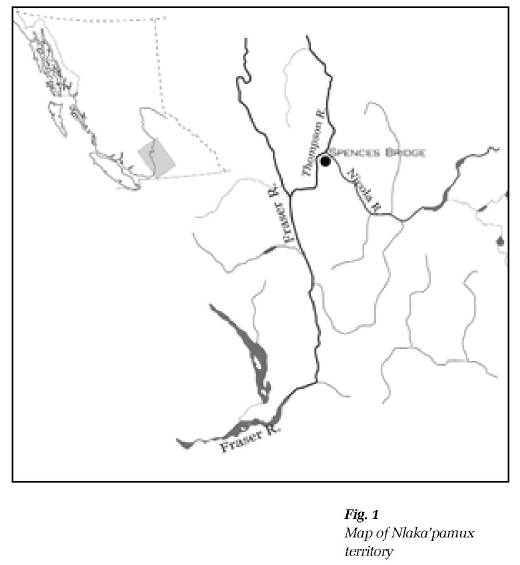

Nlaka'pamux Women's Headgear:

An Examination of Design Elements

1 The Nlaka’pamux, also known as Thompson Indians, live in the southern interior of British Columbia, along the Fraser River north of Yale to a short distance beyond Lytton, where the Fraser meets the Thompson River. Their territory extends along the Thompson River past Spences Bridge and up the Nicola River beyond Merritt (Fig. 1). This region is diverse in topography and climate, varying from the wet forest zone of the lower Fraser to the drier plateau areas around Merritt and Spences Bridge. For discussion on territory and traditional life ways, see Teit and Turner et al.1

2 This paper examines design details on Nlaka’pamux women’s headgear collected by James Teit at the turn of the twentieth century. In 1894 anthropologist Franz Boas hired Teit to under take collecting and research for the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) Jesup Expeditions.2 Teit, originally from the Shetland Islands, had married a local Nlaka’pamux woman named Lucy Artko, and had become immersed in Nlaka’pamux traditions.3 Teit collected hundreds of artifacts for museums over three decades, both used and commissioned specimens;4 most of the material he bought or gathered resides in four institutions — the AMNH,5 the Canadian Museum of Civilization (CMC),6 the Peabody Museum of Ethnology and Archaeology (PM),7 and the Royal British Columbia Museum (RBCM).8

3 Based on information provided by Teit, it is evident that Nlaka’pamux produced and wore elaborate and diverse clothing, reflecting their concern for adornment.9 Headgear was a part of a total system of body modification that included face painting, hairstyles, and highly decorated clothing. Tepper’s research in the area provides us with an excellent overview of Nlaka’pamux dress both past and present, in her publication Earth Line and Morning Star (1994) and in the exhibition Threads of the Land. Nlaka’pamux men, women and children wore ornamented headbands, caps, hat, and headdresses as is evident by their numbers in museum collections.10

4 Teit noted that men’s headgear often denoted status or occupation, yet women’s headgear did not necessarily reveal such details about the wearer.11 Tepper states that a "woman’s apparel in its use of skins and ornaments indicated her family’s wealth and status."12 Discussions with current tribal Elders confirm that men of special status wore significant hats or bonnets while everyone else wore ordinary hats or kamūts.13 Design and construction details help determine which headgear items may have been more important or may have belonged to important people.

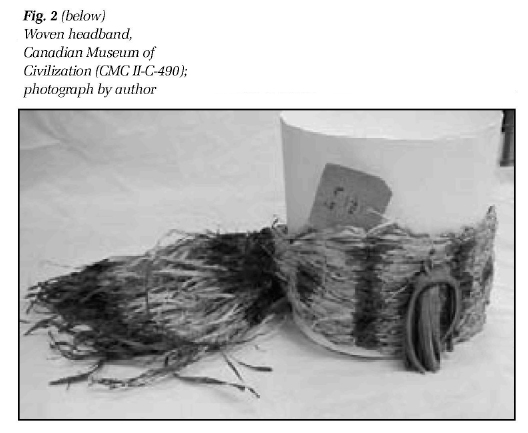

5 Caps, peaked caps, and headbands were made of either deerskin (usually tanned) or plant fibres. Plant fibres from silver willow (Elaeagnus commutata) or cedar (Thuja plicata) bark and Indian hemp (Apocynum cannabinum) were used to produce a great variety of clothing items. Teit and Tepper describe the weaving technique used in producing woven garments.14 Levels of decoration and adornment on woven headgear were usually less than that found on the deer hide counterparts. With regard to their manufacture, there appears to be no correlation between the type of headgear and the type of thread used in its construction; Indian hemp thread, commercial thread, and sinew were used. One specimen examined was sewn by machine (PH8655415).

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2 Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3Headbands

6 Teit noted that headbands were an important component of traditional dance regalia for both men and women.16 Based on the inventory of Nlaka’pamux headgear compiled by the author, it is evident that women wore headbands more often than men. Women’s headbands were made of shredded bark or tanned deer hide, sewn or fastened at the back. The most basic headbands were circlets of shredded bark fastened at the back and left to hang loose or tied into a circle without a tail. These did not involve weaving (PM86503). Woven headbands were generally simple items, consisting of a woven rectangle band attached to form a circle, with the excess bark shredded into a tail hanging down the back. The band portion was created using shredded bark for the weft yarns and warp yarns of Indian hemp or spatsum. An example of such a headband is CMC II-C-490, which is decorated with patterns of vertical lines and dots painted in red ochre. The shredded bark hanging down the back has also been painted red at the tips (Fig. 2). In his collection notes, Teit indicated that poor or elderly people, mostly women, wore woven headgear.17

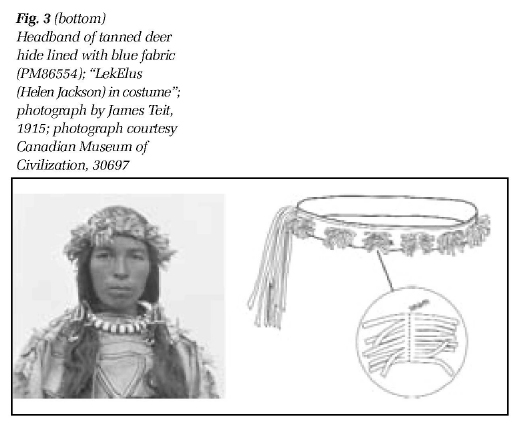

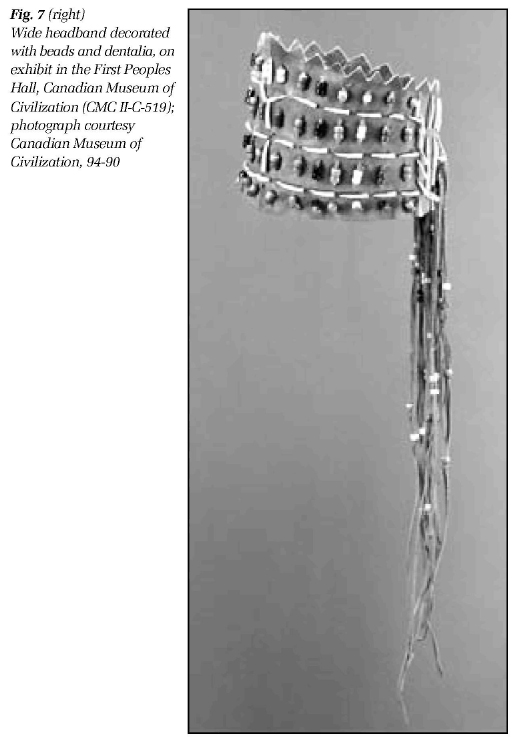

7 Deer hide headbands vary considerably in size and decoration. They were constructed in widths as narrow as 2 cm to as wide as 21 cm; wide headbands are normally narrower at the back. Many headbands have a long fringe hanging down the back. Sometimes the fringe consists of long hide thongs that tie the headband closed (RBCM2736) or a fringed piece of deer hide sewn into the back seam (PM86554; AMNH16/4596).

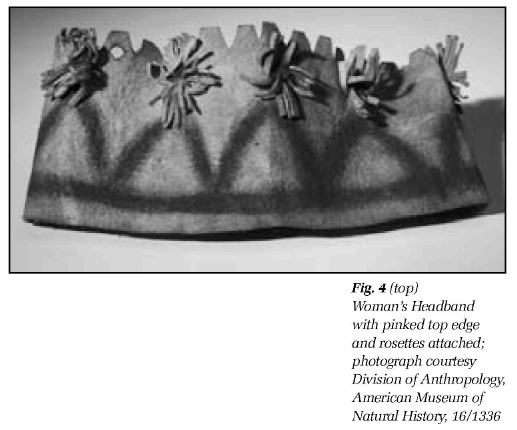

8 Rosettes are an important design feature on Nlaka’pamux clothing and headbands. Rosettes were made from round or square pieces of deer hide that have been fringed around the edge, then stitched or gathered in such a way so as to create a small bunch of fringe pointing in all directions. In his collection notes, Teit sometimes refers to such embellishments as "sunflowers."18 Judging by the number of objects in museum collections that were decorated with them, rosettes appear to have been a popular ornament on both men and women’s clothing. A narrow deer hide headband, lined with blue cotton fabric has eleven rosettes attached around the band (Fig. 3). The liveliness of the rosettes is set off with red ochre daubed on the underside of each. A wide headband at the AMNH (AMNH16/1336) is decorated with similar rosettes, each painted red in the centre (Fig. 4).

9 Nlaka’pamux people employed serrated or pinked edges as a decorative technique to soften an edge or to create a more dynamic outline. Clothing items often include pinked edging on bibs, collars, plackets and cuffs on clothing of both sexes.19 AMNH16/1336 and CMC II-C-519 have serrated top edges. The former has a blunted serrated edge (Fig. 4) while the latter has a pinked edge (Fig. 7). Pinking is also used on deer hide appliqués stitched on to headgear and garments.

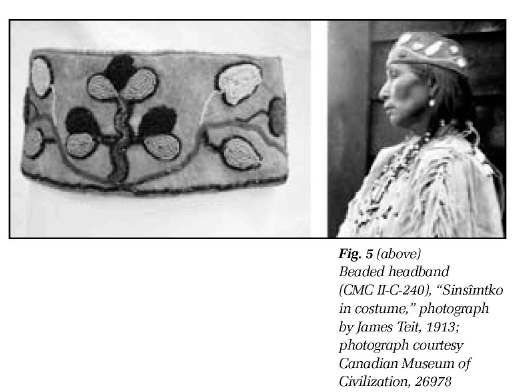

10 By the time Teit undertook his collecting work, Nlaka’pamux people had had access to European manufactured goods for several generations. Explorer and fur trader Simon Fraser was one of the first Euro-Canadians to enter Nlaka’pamux territory. His cursory observations about people he encountered tell us that he found the people of this region well dressed in deer hide clothing, adorned with shells and paint.20 In the early nineteenth century, fur trade posts were established at Kamloops and later at Yale, providing the Nlaka’pamux with a source of Euro-Canadian manufactured products. Nlaka’pamux seamstresses purchased and used imported glass beads to decorate headgear and clothing yet did not develop the solidly beaded styles of Native peoples in the Plains or Subarctic regions.21 The most heavily beaded specimen is CMC II-C-240, which has flowing floral motifs circling the headband (Fig. 5). The beads were strung onto a cotton thread that was then couched on to the headband. A variety of coloured glass seed beads was used: yellow, powder blue, white, navy, purple, pink, medium blue. The leaves and petals are delineated with a row of dark brown beads, which are also used to accentuate the headband’s bottom edge.

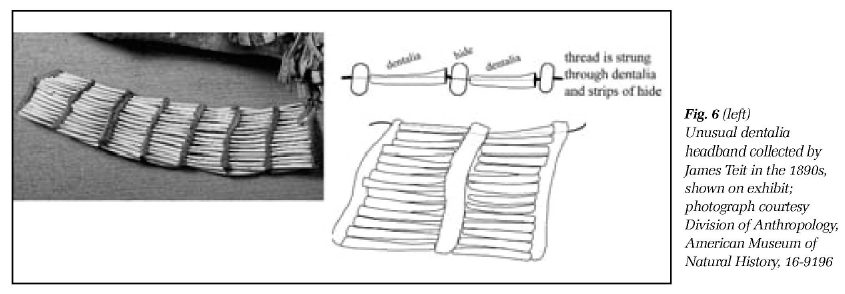

11 Predating the availability of glass beads, dentalia22 were used throughout coastal and interior Plateau regions to decorate clothing. A narrow headband at the AMNH (AMNH16/9196) is made of dentalia laid down horizontally in vertical rows, joined with hide thongs (Fig. 6). This technique is similar to that used in the production of bone tube chokers and breastplates made by Aboriginal people on the Plains. This is the only example of its kind, so it may represent an "old fashioned" style23 or is an anomaly. Teit does not describe this object as unique in his collector’s notes.

12 Dentalia and large glass beads adorn an attractive wide headband at the CMC (CMC II-C-519). It is made of caribou hide and reveals several Nlaka’pamux decorative techniques. The top edge is serrated and long fringes strung with large glass beads hang down the back. The headband is embellished in the centre and along the sides with three rows of dentalia laid horizontally and secured with hide thongs woven through the material. Within each row, there are large glass beads stitched down in a vertical design in a one and two-bead composition. Dentalia are secured vertically at the back (Fig. 7).

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4 Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5 Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 6 Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 7 Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 8 Display large image of Figure 9

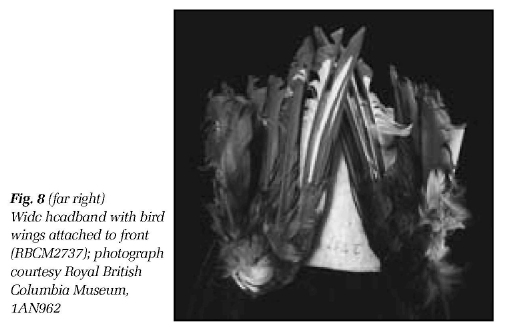

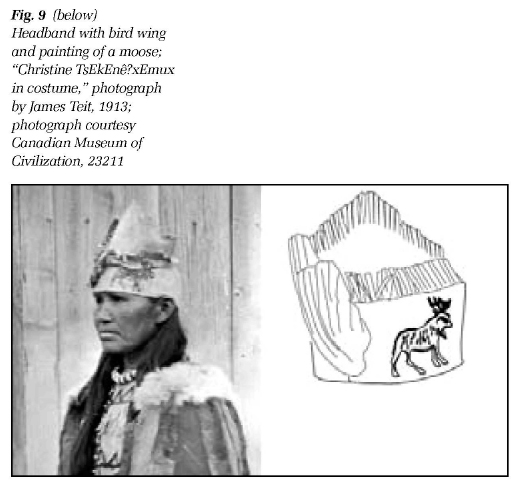

Display large image of Figure 913 One of the most striking features of Nlaka’pamux headgear is the use of bird and animal parts for decoration. Some men’s headgear examined by the author is quite dramatic in the use of fur, feathers, and even entire bird skins as adornment. Women’s headbands are rarely trimmed with such embellishments. The two examples discussed here have complete wings attached. RBCM2737 is constructed of parchment (untanned) deer hide with two magpie wings attached to the front, positioned so the points of the wings stick up (Fig. 8). PM86595 has one complete Northern flicker wing attached to the right front; this is balanced with a drawing on the other side, in red, of a moose (Fig. 9). Teit collected both headbands but did not provide comment on their unique nature.

Caps

14 Examination of the four major collections discussed here suggests that Nlaka’pamux women did not wear woven caps. They wore two styles of caps constructed of tanned deer hide. The first type of cap consists of two pieces of deer hide sewn together with a centre seam running the length of the cap, usually from front to back, similar to a military highlander cap. The other style is a pillbox cap or fez, made of a large rectangle sewn together with a circular or oval top. Embellishment of caps went beyond that of headbands to include more sewn in fringe, fur and bead decoration.

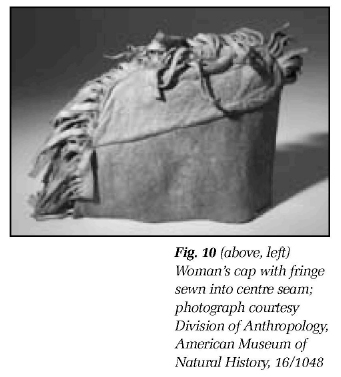

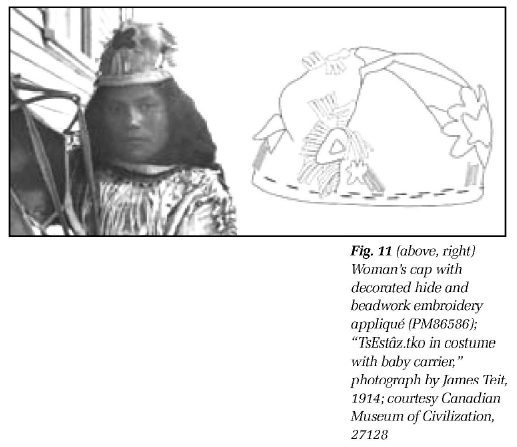

15 Nlaka’pamux seamstresses made use of a sewn-in fringe as a decorative detail on numerous clothing items.24 In the specimen AMNH16/1048, a length of fringe has been sewn into the centre seam of the top two sides (Fig. 10). The fringe falls on either side of the top seam. Several caps have a fringe sewn around the bottom edge, pointing upward. This fringe is usually quite short so that it splays out a bit. Some caps include decorative details or appliqués, which are accented with fringed pieces of hide. PM86586, for example, has small, irregular pieces of fringed hide sewn beneath a beaded triangular appliqué (Fig. 11).

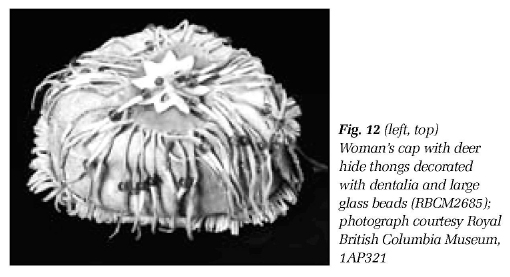

16 Some clothing was decorated with fringe made of hide thongs stitched on to or threaded through the garment. Where the fringe was very long, it was often strung with large glass beads, dentalia, tinklers, or similar items. One cap at the RBCM has this fringe treatment (RBCM2685). A series of hide thongs emerge from the top centre seam so that they fall down all around. These thongs hang the depth of the cap and each one is decorated with a large glass bead and dentalia shell (Fig. 12). Additional fringes emerge from the star-shaped appliqué attached to the top centre of the cap. This cap also has a short, upward-pointing fringe sewn into the seam of the bottom rim.

Display large image of Figure 10

Display large image of Figure 10 Display large image of Figure 11

Display large image of Figure 11 Display large image of Figure 12

Display large image of Figure 12 Display large image of Figure 13

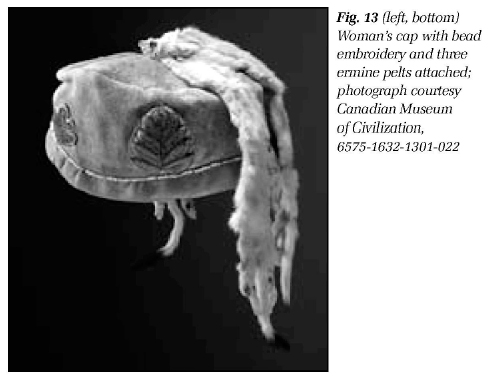

Display large image of Figure 1317 Women’s headgear did not include fur appliqué or small animal skins to the same degree as did men’s. Men’s caps made of fur or decorated with fur sometimes indicated the wealth and ability of the wearer. According to Nathan Spinks of Lytton, B.C., the Nlaka’pamux believed they could absorb the power of an animal by wearing parts of that animal or decorating their garments with its image. As such, young boys would wear furs of rabbit or chipmunk while high ranking men would wear lynx or coyote furs, for example. Teit’s discussion of power and headgear relates exclusively to men and Spinks did not believe that women wore animal furs for the same reason as men. Without documentation to support the theory, it would be hazardous to suppose that women also gained power from wearing animal furs. There are women’s caps decorated with fur in the collections discussed here. PM86573 has a crown of marmot skin and an ermine skin draped over and stitched to the top of one side. A squirrel skin is attached to the side opposite to the ermine. It is decorated with bead work embroidery representing an eagle, eagle’s nest and eagle "tracks." It is slightly dirty and may have been collected from the original owner. A fez-type cap at the CMC (Fig. 13) is decorated with solid beadwork patches around the sides and a beaded line delineating the bottom rim. These were described as representing "earth line and trees."25 Three casement26 ermine skins are attached to the top centre point and left to hang down the back. The quality of the materials used and their overall appearance might suggest that these hats were worn by wealthier individuals.

Peaked caps

18 Some of the most stylish hats worn by Nlaka’pamux women are the tall and short peaked caps, constructed of either deer hide or woven bark. The author uses the term peaked caps to designate those caps that are constructed with a point at the top of the head. Regardless of material used to make the cap, this type of headgear often contained a significant amount of embellishment and trim.

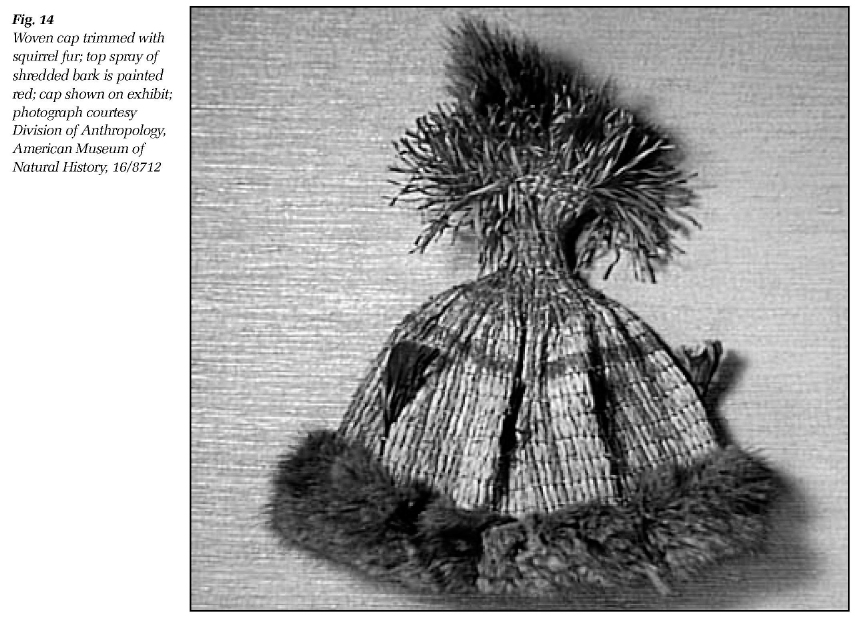

19 Using the same weaving techniques employed in producing headbands and capes, Nlaka’pamux women wove caps in the round, creating tall, peaked or small, rounded caps. These were not woven caps in the style of basketry hats worn by Plateau peoples farther south.27 Warp yarns consist of shredded bark while weft yarns are normally Indian hemp twine, which is twisted around the slivers of shredded bark. Most woven caps were constructed from the bottom hem so that the selvage forms the rim and loose ends form a spray of shredded bark at the top. All silver willow caps made in this technique have red ochre painted on the area where the yarns are brought together, just under the spray. In addition, woven hats and caps almost always have some sort of painted design, usually dots and/or strips executed in red ochre. One round cap, AMNH16/8712, is woven with dyed and natural yarns. The yarns were arranged to create a vertical triadic pattern around the circumference (Fig. 14). The top half of the cap is enhanced with a broad line running horizontally around the cap.

Display large image of Figure 14

Display large image of Figure 1420 Most woven hats are trimmed at the bottom edge with tanned deer hide or fur, probably to make the item more comfortable to wear. RBCM2733 and AMNH16/8712 are edged with muskrat and squirrel fur respectively. When deer hide is used, the rim is often decorated with paint or fringe. Some caps have a piece of fringed hide wound around the top peak of the cap (RBCM2733, PM86498).

Display large image of Figure 15

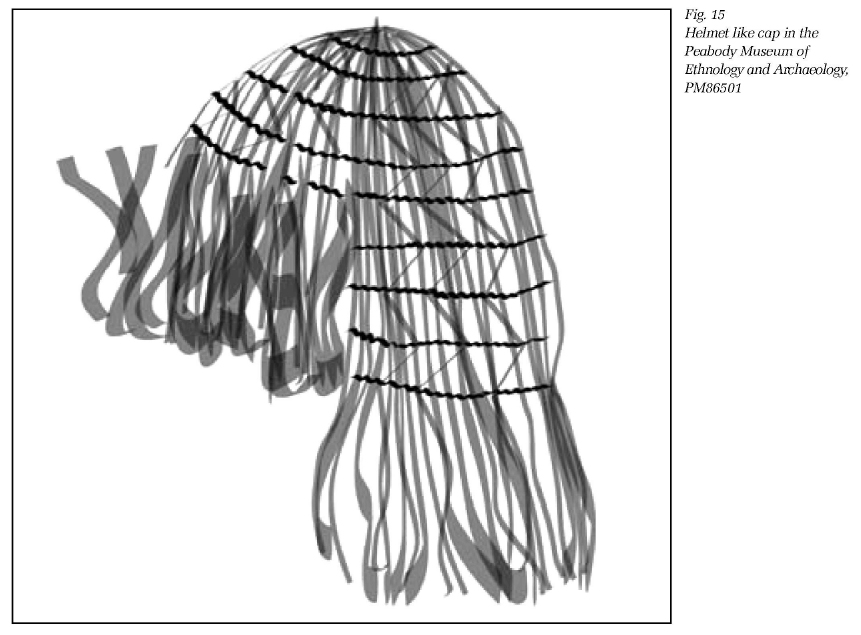

Display large image of Figure 1521 A unique helmet-type hat from the Peabody collection includes an interesting design over the surface. This hat appears to have been constructed "upside down" in that the loose yarn ends create a fringe around the bottom rather than a spray at the top. The hat has dyed red vegetable fibre yarns threaded through the weft yarns in a zigzag pattern (Fig. 15). The surface pattern runs from the peak of the cap to the bottom edge; at this point, the dyed yarns are incorporated into the fringe at the bottom. Around the face area, the loose warp yarns are turned up and fastened, creating a fringed brim. Unlike other woven caps, this one does not have a spray of shredded bark at the top.

22 Deer hide peaked caps were constructed in two ways. The first method involved cutting deep notches into a rectangular piece of hide then sewing it together, bringing the top to a point. The second approach was to sew several triangular panels together, creating a point at the top. The height of the caps examined ranged from 16 cm to 26 cm. The construction of these caps, with multiple vertical seams, lends itself to the inclusion of sewn in fringe.

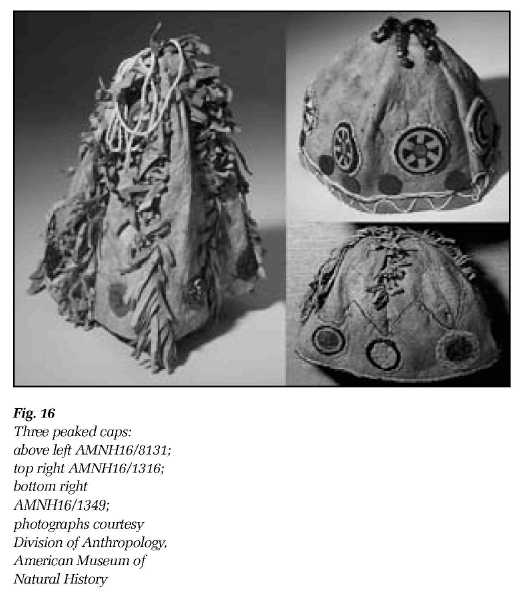

23 Three peaked caps examined have round medallions embroidered with glass seed beads (Fig. 16). On AMNH16/1316, the beadwork is done on round pieces of red fabric, probably wool, using the couched thread technique. The cap has seven bead work medallions attached; four medallions are simple round patterns made up of concentric round circles while the other three are a geometric wheel pattern. On AMNH16/8131 and 16/1349, the round motifs were embroidered directly on to the cap. The circles are created by couching down long strings of beads in a circular pattern, starting at the centre and working outwards. Two caps are decorated with strings of beads hanging from the top centre point. On AMNH 16/8131, long strings of white glass seed beads are secured to the top, falling down in loops. Short hide thongs strung with large glass beads are attached to the centre peak of AMNH16/1316. Each of these thongs ends in a brass button or small bell. Two caps are decorated with a short fringe sewn into the seams. In the tall cap (AMNH16/8131), there are two fringed hide pieces sewn into the length of each seam resulting in a lively silhouette. The second example (AMNH16/1349) has shorter fringe sewn in the seams running half way down the cap. A zigzag line of beads stitched around the cap’s circumference separates the fringe and beaded circle decorations.

Display large image of Figure 16

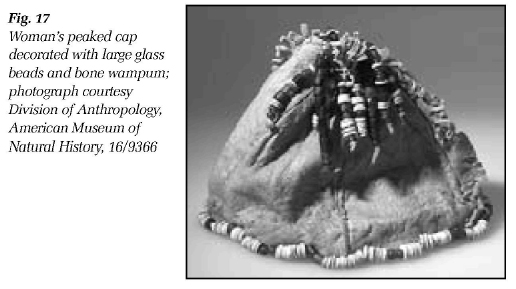

Display large image of Figure 1624 A short conical cap AMNH16/9366 has large glass beads and clamshell wampum28 decorating the top and bottom edge in addition to sewn-in fringe running the length of the centre seam (Fig. 17). The cap is asymmetrical with two panels on one side and three panels on the other side of the central seam. Nine thongs decorated with a variety of large glass beads (multifaceted, round and cut beads in blue, amber and green) and bone wampum descend from the top peak. A string of bone wampum and beads decorate the bottom edge.

Display large image of Figure 17

Display large image of Figure 17Discussion

25 As mentioned earlier, non-Native influence in the Nlaka’pamux region began with the fur trade in the early nineteenth century. Christian missionaries began arriving in the area in the 1840s. Non-Native peoples became more permanently established in Nlaka’pamux territory after the 1858 Cariboo gold rush when many people settled to establish agricultural homesteads. These foreign influences had a profound effect on traditional aboriginal clothing. Photographs taken in the late 1900s reveal that most Nlaka’pamux people at this time were dressed in the Euro-Canadian style.29 Yet Nlaka’pamux headbands and hats as represented in the museum collections rarely reflect any obvious European influences, such CMC II-C-496 (Fig. 13) and perhaps PH86554 (Fig. 3), which is machine-sewn.

26 Nlaka’pamux women’s traditional dress included several types of caps, hats and headbands. Ornamentation of these headgear items reflected the types of decoration found on clothing items such as dresses, tunics, and capes, also found in abundance in the museum collections discussed here. Much of Nlaka’pamux material culture is coloured with red paint in varying amounts. Practically all clothing articles, drums, and ceremonial items include daubs of red paint or painted designs and/or motifs. The Nlaka’pamux viewed, and continue to view, red as a colour imbued with power.30 Traditionally, the paint was made from red ochre obtained locally or vermilion obtained through trade. According to Harlan Smith, there were three locales for obtaining red ochre in the southern Plateau region: Adams Lake, Vermilion Forks on the Similkameen River, and Bonaparte.31

27 While red paint appears to be the one constant in the decorative repertoire, even a cursory examination of Nlaka’pamux material culture reveals their interest in using ideas and objects from nature for adornment. Teit’s use of the term "sunflower" to describe a fringe treatment (discussed above), for example, may come from the Nlaka’pamux people’s own description of this decorative motif. In the story "Old-One teaches the People the Use of Ornaments," Teit recorded the story of how Nlaka’pamux came to adorn their clothing:

28 Teit has suggested a link between the basketry hats of the Sahaptian peoples to the south though no direct evidence has emerged from published research. The southern basketry hats are made in the twined basketry technique, that bear little resemblance to those found in the Nlaka’pamux collections. Nlaka’pamux women wove hats and caps in a manner similar to their capes and mats, rather than in the style of their baskets. Some similarities may be noted in that some peaked caps have strings of beads or hide thongs (plain or decorated) emerging from the top centre to hang down, similar to the hide ties on basketry hats.33

Conclusion

29 When examining any historic collection, it is imperative to consider the ability of that collection to represent the whole picture. We know that Teit com missioned articles for museum collections and it is evident that some headgear items were quite new when they were purchased. I am confident that the techniques employed by Nlaka’pamux women in constructing and decorating headgear discussed here were authentic, and that they reflect the broad spectrum of Nlaka’pamux styles, patterns, and design ideas. Indeed, one might conclude that variety and invention were key factors in Nlaka’pamux design aesthetic. This idea has been suggested in recent interviews with elders and artisans.34

30 The colourful embellishment from glass beads, ribbon, or embroidery floss was used sparingly for the most part. Glass bead embroidery, which many people identify with Aboriginal clothing, is only one component of the Nlaka’pamux decorative repertoire. Using pinking, fringes, paint, feathers, fur, dentalia, rosettes, and appliqués in dramatic and unique combinations has resulted in a strongly identifiable decorative tradition, evident on their headgear as well as traditional garments. Deer hide headbands and caps have the greatest variety of adornment features. Peaked caps were commonly decorated in a manner that allowed the design to move around the cap with additional accentuation of the top peak. Woven headgear by its nature and use was generally less decorated but usually contained some embellishment.

31 Further studies into men’s and children’s headgear, also available in these four major collections, will assist in expanding the information base of Nlaka’pamux dress and adornment. The Nlaka’pamux women’s headgear provides us with a sense of the Nlaka’pamux aesthetic and design standards. This information is valuable, not only in the museum context, but also to the Nlaka’pamux themselves who continue to re-examine their material culture, passing on information and traditions to younger generations.