Research Reports / Rapports de recherche

The Trappers of Labrador

1 The Liveyers1 of Labrador derived this name by which they called themselves from "livers here" to distinguish them from migratory summer fishermen from Newfoundland, England and the New England states. John Parker2 estimated in 1950 that the Liveyers of Labrador numbered 3000. They were a hardy breed of people for which — in the age before commercial and military development came to the country—there was no stronger tradition than that of hunting and trapping. Liveyers were also fishermen and often joined visiting fishing fleets for the season or fished on their own account. Fishing was but one source of food and income that helped sustain them.

2 In the fall, winter and spring, Liveyers relied on hunting and trapping. Indeed, for well over two hundred years, before and after the Second World War and the construction of Goose Bay for use by the United States Air Force, the Liveyers knew no other life. As the daughter of one trapper3 remarked with sardonic humour, "We lived off the fat of the land and most years the fat was thin."

3 The Liveyers were a homogenous people. Among them are found traces of English, Irish, Scots, Welsh, French, Flemish, Portuguese, Inuit and the indigenous Nascaupi Indians of the Quebec North Shore. Their language shows evidence of archaic English and has much in common with the American English of New England in the way it adds new phrases to the language with refreshing simplicity. For example, the past tense of the verb to fly becomes flid as in "He haven't flid yet."4 Their language is as direct and colourful as anything created by their Newfoundland cousins: "The glass dropped like a hot potato," speaking of the barometer, and "Enough to blow your eyes out," of a raging gale. The Liveyers also retain in then-speech such words as thee and thou and gotten.

4 In his account5 of a journey of exploration from Nain to Indian House Lake in 1910, the explorer H. Hesketh Prichard wrote:

Many years after Hesketh Prichard wrote this prophetic passage, geologists discovered minerals in abundance in Labrador. In 1954, the Iron Ore Company of Canada opened its mammoth iron ore operations at Knob Lake.6 Experimental harvesting of the territory's high-grade pulpwood began, hydro-power development started at Twin Falls to supply another iron ore operation at Labrador City, the Churchill Falls was being planned and, later still, rich nickel deposits were discovered at Voisey's Bay.

5 The effect of the commercial development and land claims of the indigenous Inuit has been felt by none more strongly than the Liveyers who, until recently — recently in terms of white man's history in Labrador — depended on the results of each season of trapping to sustain themselves and their families. The tradition of trapping was handed down from generation to generation, from father to son and, in some instances, father to daughter.

6 Within the narrow confines of the Liveyer community the names of Blake, Goudie, MacLean, Montague, Michelin, Chaulk, and White read like a selection of the most honoured names from Burke's Peerage. These names have become part of Labrador's geography, of its rivers, creeks and lakes: Susanne, Hamilton, Melville, MacKenzie. Those names by which other major features of the territory's geography are known are, incidentally, of distinctly Indian origin—Ashuanipi, Michicomau, Ossukmanuan, Nascuapi. Only the coastal mountains to the very north of Labrador bear names of Inuit origin—the Kiglapait Mountains,7 for example.

7 Liveyers have served as faithful retainers to such well-known personalities as Grenfell,8 Peacock,9 Paddon,10 Prichard and Hubbard.11 It is ironic that Yale Falls, Thomas Falls,12 and the Kipling Mountains were known to the Liveyers long before the same places and features were discovered by the later, intrepid explorers. With or without explorers or outside help, the Liveyers eked out an existence and survived the harsh wilderness.

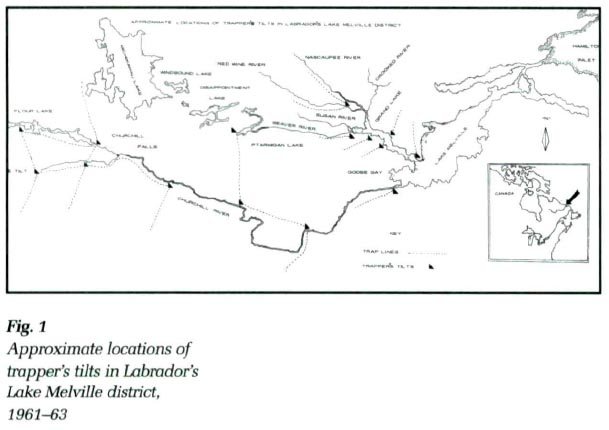

8 It is difficult to establish how long ago the various families, mostly of the community of North West River, settled on the trapping areas that came to be associated with particular families. One thing, however, is certain — trap lines were not settled by right of conquest. The Liveyers were too busy fighting a savage environment to squabble about who should trap where. In the Lake Melville District, trap lines extended along the length of the main artery of the territory, the Grand River, like the veins of a leaf.

9 During the first half of the twentieth century, the Labrador fur trade flourished with pelts of mink, otter, marten, fox—all bringing prices never reached before or since. The annual trek to the interior began in late September when the snow was already on the ground. Trappers left by canoe for the long and hazardous journey up the Grand River. Those with trap lines in the Grand Lake area (Fig. 1) and near enough to be within striking distance of home would return for Christmas and set out again in the new year to complete the season in the bush. In contrast, those with lines beyond Churchill Falls, at Flour Lake and along the Unknown River, stayed in the bush the entire season, coming out just before or during the spring break-up.

10 For men who were to spend months tending trap lines alone, they travelled light. A supply of sugar, flour, tea and salt formed their staple provisions with a small amount of raisins and chocolate to tide them over the Christmas period. They were often without these latter items of luxury. Whatever else the trapper carried with him, nothing was as important as his short-handled trapper's axe. He relied entirely on this razor-sharp tool to see him through the season. Without it he was as a soldier without his arms, for he used it to make his traps, pelt boards, toboggans and his home away from home, the trapper's tilt.

11 Evidence of the skill with which the trapper used his axe is to be found in the odd derelict and abandoned tilt to be found occasionally in the bush. The tilt was both a trapper's winter house and an overnight shelter built along a "trap line" or "fur path." Trappers measured distance in terms of tilts. "We had to go four tilts distance — roughly fifty miles [82 km] one way."13

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1 Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2 Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 312 The tilt was a remarkable utilitarian structure that compares favourably with the most resourceful dwellings devised by humans: the igloo, kraal hut, and Bedouin tent, in which only locally available material is used. The tilt was made entirely of hewn and notched spruce logs cut and trimmed to fit rightly together without the use of a single iron nail. The angled roof, tilted laterally to form a gabled end, was packed with caribou moss to make it weather proof. Caribou moss is a lichen greeish-grey in colour with a sponge-like texture that makes it ideal for sealing the walls and roof. A two-feet square opening at the tilt's gable end formed the entrance and could be closed from the inside with a piece of canvas or, more likely, caribou hide.

13 The trapper constructed his tilt at the edge of the forest, probably along the shoreline of a river or lake. To insulate the floor of the dwelling, the trapper laid a bed of alder twigs covered with the same cribou lichen used for caulking the walls and roof. A portable stove fashioned out of a long, rectangular hard-tack14 biscuit tin provided the tilt with heat. A short stove pipe vented the stove through the roof. The finished dwelling was about 3 metres long by 2 metres wide by 1 to 1.5 metres in height to the apex of the roof. It was a squat building that hugged the forest floor. In the depth of winter with snow falling off tree branches like clotted cream and the cold stretched as tight as a drum, the trapper's tilt was as snug as a bear's cave. The temperatures in a Labrador winter falls to 40ºC and -50ºC for days on end.

14 The trappers of North West River spurned the use of guns and metal traps, for they were heavy, difficult to carry, and easily lost. Besides, guns, ammunition and ironmongery were beyond the financial resources of the trapper. With his axe, he made all the implements he needed: traps, boards, scrapers, toboggans. Pelt boards were used to stretch the pelts of animals and remove the fatty layer of tissue, a necessary chore to preserve the pelt.

15 Like a tilt, the trapper's toboggan was of an unusual design. Up to 2 metres in length, the toboggan was fashioned from two planks of 46-cm wide spruce, cut and shaved into sheets with the axe used as an adz. The ends that formed the head were steamed and curved upward when assembled. The two lateral sections were secured to the cross braces with thongs made from caribou hide. High at the prow, broad in the beam, slender and flexible, the toboggan when loaded flexed easily over hard and soft snow so that the tapered tail end met with little resistance. With a skilfully distributed load, the main weight at the broad section, the toboggan was beautifully balanced. With a well-designed and fashioned vehicle an experienced trapper could haul up to 360 kg of pelts, equipment and supplies.

16 Trappers worked their trap lines every three or four days, camping overnight along the way. Clipping the bark of marker trees (blazing the trail), the trapper laid a path through the densest bush. Even during the short Labrador summer these trapper's trails are still clearly visible to the observant eye. Trap lines were between 80 km and 95 km long — "four tilts distance." That is, on well-established lines, the trapper sheltered in make-shift tilts, meaning that they were not as substantial as the trapper's base camp tilt. He might also erect a canvas tent if a tilt was not available.

17 Considering trappers lived and worked in sub-zero temperatures, a well set-up tent was surprisingly warm and comfortable. For this purpose, the trapper chose a sheltered place well inside the tree line. Using his snow shoes, the trapper compacted a declivity in the snow, which was always deep and soft in the shelter of the spruce trees. He set the tent in the hole on a bed of black spruce branches. Next he laid a bed of caribou moss, the same as in his home tilt, then overlaid the floor covering with a rug carried for the purpose or bear skins if these were available.

18 The tin stove with its vent pipe poking jauntily through the canvas and stoked with alder twigs provided all the heat needed. Regardless of the sub-zero weather, the inside temperature of a well-placed tent could be raised to 32°C. In a small stove, however, the fire needed stoking every hour or so. This the hardy trapper did throughout the night as part of the established and necessary pattern of his sleeping hours in the bush.

19 The trapper lived on a healthy diet of spruce partridge, caribou steaks, ptarmigan stew, snow buntings, salt pork, and flat bread made of flour, salt and water cooked in an open pan over the fire. Supplies of caribou meat were cached high in the air between a pair of trees to keep it out of the reach of marauding wolves and bears. Properly prepared, cached caribou meat was good for a year even though the heat of a summer's day could soar to 30°C. To prepare a cache, the outer layer of meat was burnt to a crisp over an open fire. Searing the meat over an open fire to form a hard, black shell protected the meat from mosquitoes and black flies.

20 To protect themselves from black flies and mosquitoes during the summer months, trappers used a method learned from the Nascaupi Indians: juice squeezed from the leaves of the Labrador tea15 plant formed a natural and long-lasting insect repellent when smeared over the skin.

21 Ingenuity saw many a trapper overcome adversity in times of crisis. The bush telegraph was a wonderful means of exchanging messages when isolated for long periods. There was the story of Jim Goudie working his trap lines in the upper reaches of the Churchill River16 when word came to him that one of his children was stricken with measles, a serious matter before the discovery and use of antibiotics.17 To return to North West River with all haste, Jim used the river as the quickest means of travel.18 The only canoe he could find was several years old and severely deteriorated. The canvas had rotted and the skeletal frame was all that remained of the craft. Undaunted, Goudie upturned the canoe on the ice at the river's edge and poured water over the ribs to form an ice shell. Then, having shaved a smooth surface with his axe, he gingerly lowered the canoe into the river and loaded in his gear, pelts and all to paddle his way among the ice pans and fast flowing river to the head of Muskrat Falls 130 kilometres downstream.

22 Goudie's journey in an ice boat in the late 1930s has become part of the folklore of Labrador and, like the trapping community itself, now all but extinct, it is part of the territory's history. With the rise of commercial and economic development, and the opening up of Labrador to mining, the way of life of the Liveyers has all but disappeared.

23 Trappers now share the fate of such pastoral occupations as shepherds, coopers, blacksmiths and harness makers. They are a vanished breed of men swept away by the inexorable march of civilization. Nevertheless, with the corning of the power shovels of the iron ore mines to gouge the landscape and the rise of hydro-power developments with their dams holding back the water in massive fore-bays, none would appreciate more than the old trappers of Labrador the observation of Hesketh Prichard that "the problem of existence is solved by successful destruction."