Abstract

As they travelled from the northeastern seaboard across the Great Lakes region, French missionaries and explorers experienced indigenous foodways, particularly a boiled mixture of corn in various states, with similarly varied states of fish, meat, or berries. They termed the meal sagamité after an Abenaki term for the dish, but in the Great Lakes region versions like it survive under the term booya especially, possibly derived from French descriptions of the preparation method. This presentation will explore the indigenous foundation for this meal, describe similar contemporary northwestern Great Lakes versions, and suggest the strong influence of the French in naming it.

Résumé

Au cours de leurs voyages de l'Atlantique à la région des Grands Lacs, les missionaires et les explorateurs français ont expérimenté les produits alimentaires des autochtones, plus particulièrement un mélange bouilli de maïs sous diverses formes et de poissons, viandes ou baies aussi diVere. Ils ont nommé ce mets sagamité d'après sa désignation abénakise mais quelques variantes du plat subsistent plutôt sous le nom de booya, peut-être dérivé des descriptions françaises de sa préparation, dans la région des Grands Lacs. Cet article se penche sur l'origine autochtone du mets, décrit les versions de la région nord-ouest des Grands Lacs et suggère la forte influence du français sur son appellation.

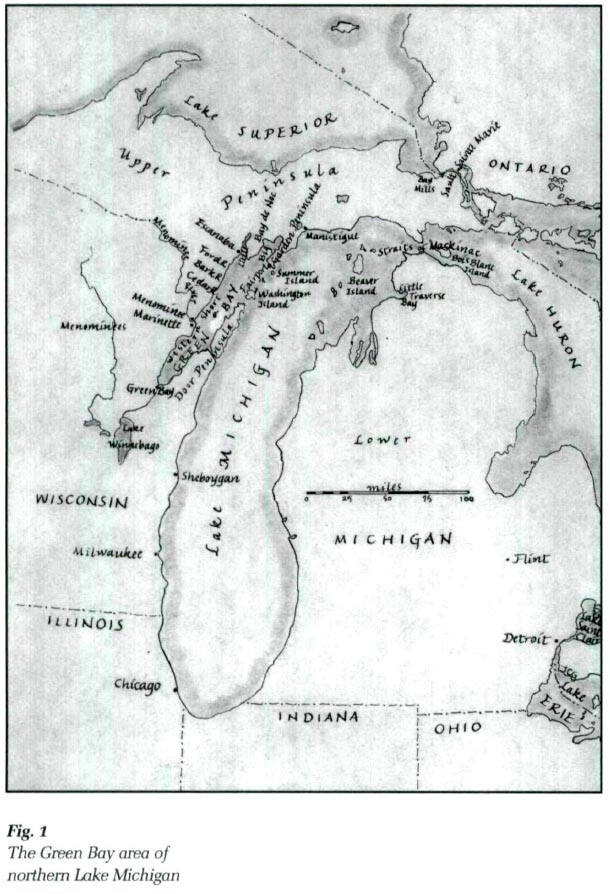

1 Wisconsin, a Great Lakes state, is identified most often with the woodland, prairie, and agricultural features of the terrestrial Upper Midwest and contiguous Plains. However, the state is physically defined by important bodies of water on three sides: the western shore of Lake Michigan on the east, the southern shore of Lake Superior on the north, and the upper reaches of the Mississippi River on the west. When I moved to the state in the 1980s, these rich and watery margins attracted me, and I happily accepted many opportunities to document commercial fishing traditions that flourished in the greater region, particularly ones involving fishing boats, fishing gear, and fish foodways.2 During the late 1980s and early 1990s, a series of contract jobs returned me several times to the western Upper Peninsula of Michigan and northeastern Wisconsin around and near Lake Michigan's Green Bay (Fig. 1). In 1989-90, an assignment from the Michigan Traditional Arts Program of the Michigan State University Museum in East Lansing specifically requested the investigation of fish foodways among commercial fishing people who inhabited the western shore of Green Bay.3 In recent years I have been furthering this research, the fish food-ways material especially, by exploring the historical record.4 This paper focuses on some intriguing parallels that appear to persist between contemporary non-tribal fish foodways and those recorded among tribal populations especially during the early contact period of the seventeenth century. It represents an initial inquiry, of sorts, with the purpose of requesting and identifying additional sources, especially from Canada, for delving into boiled (fish) dinner traditions in the greater Great Lakes region.

2 In northeastern Wisconsin and the southwestern Upper Peninsula of Michigan, there are two well-known boiled dinner traditions, a "fish boil," and a booyah, which generally does not incorporate fish, but for which there is a "fish booya" version. At the end of the twentieth century and heading into the twenty-first, the fish boil is one of the most distinctive meals associated with the Green Bay area, most strongly with Wisconsin's Door Peninsula, which juts northeast into Lake Michigan, in fact it is often referred to as "the Door County fish boil." During the twentieth century, it was a common preparation for times when whitefish especially were abundant during the summer, when fishermen had a good catch and nice weather while fishing, and when their families might have guests.

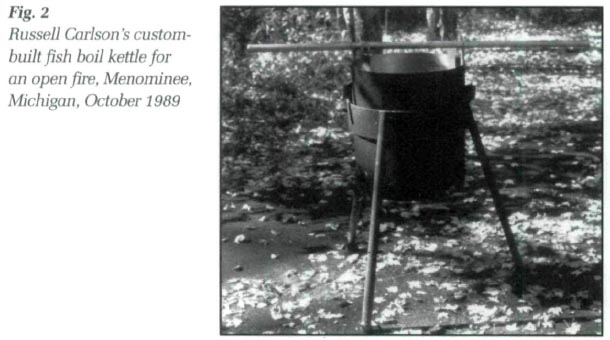

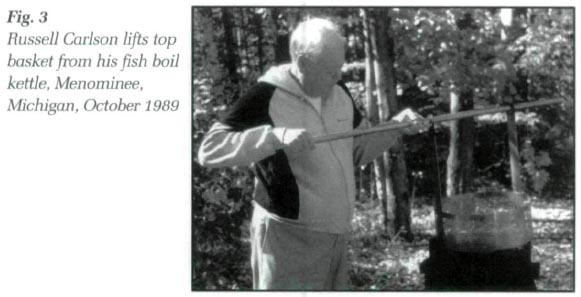

3 In the traditional fish boil, chunked lake trout and/or whitefish (with the skin on and bones in), whole new potatoes, and whole, peeled onions, are boiled in heavily salted water, sometimes seasoned with pickling spices, in large, specially-made kettles. The late Russell Carlson of the Menominee-Marinette area, who used to offer private fish boils for friends half a dozen times a summer, figured on each whitefish, with around a kilogram of edible flesh, feeding 2 to 3 people; he would cook 3 to 4 small new potatoes "cooked in their jackets" and 2 whole onions per person. He added 250 ml of salt to the boiling water for a batch that included 10 to 15 kg of fish; he did not add a pickling spice mixture to the boil as many along Green Bay's western shore do, but he provided his guests with melted butter to season their meal delectably. He and his wife Janet served the meal with coleslaw, baked baby Lima beans, bread, and beer or cocktails. Carlson was so focused on the fish boil component of the event that he claimed he paid little attention to what desserts might be offered: "maybe apple turnover on a dish," he conjectured.5

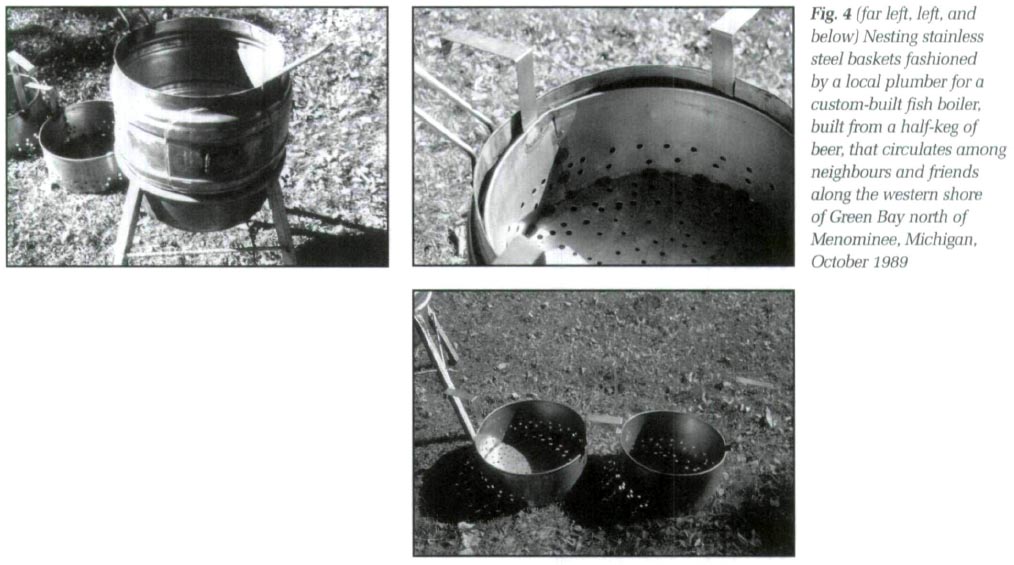

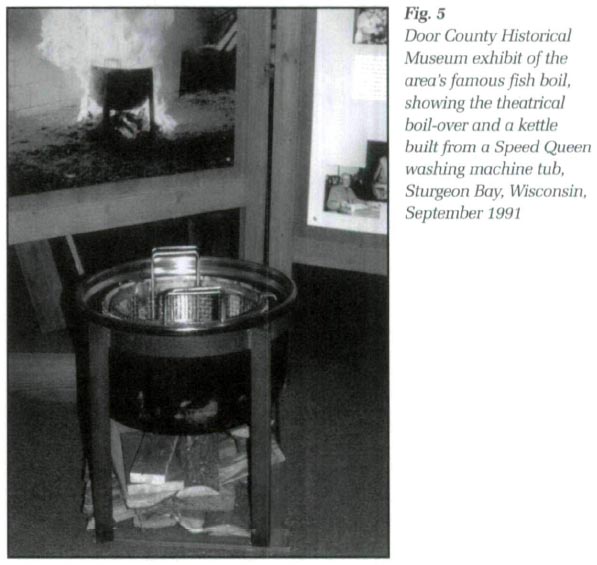

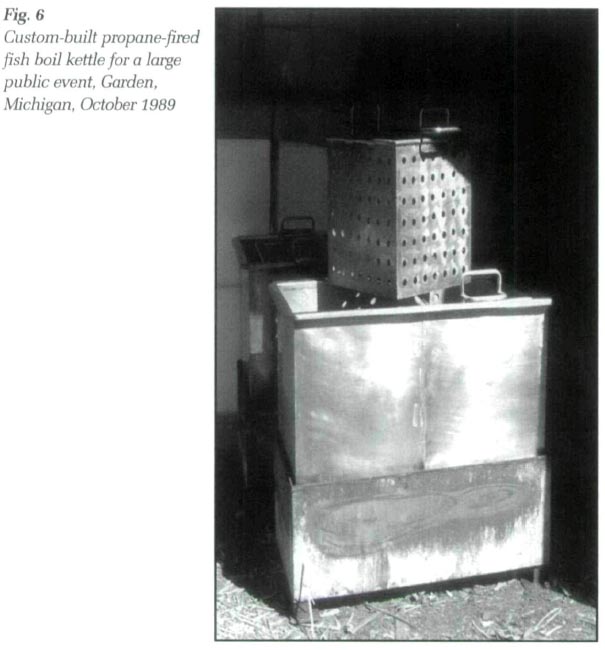

4 Traditional fish boil kettles (Figs. 2 and 3) generally hold two stainless steel baskets which can be lowered and raised easily from the boiling water, and which protect the ingredients from disintegrating as they are cooked and then retrieved. The handles of the top basket fit inside the handles of the lower (Fig. 4). Potatoes first, and then onions, go in the lower basket, and fish in the upper one. Each ingredient has a different cooking time, with potatoes of fairly uniform size added first, smallish onions second, and fish for the last 5 to 8 minutes or so. The cooking liquid is not consumed, and in boils cooked over an open fire, the liquid is deliberately boiled over the sides of the kettle during the last moments of cooking, taking any foam or scum that may have accumulated from the cooking ingredients with it. Fuel sprinkled onto the fire produces a spectacular, showy flare-up (Fig. 5), announcing the meal is ready for the eagerly awaiting audience. The stainless steel kettles for large feedings are built to be heated in an open fire, but more recent versions for even larger groups are accommodated for propane and take a different shape (Fig. 6). The kettles have often been obtained from friends with welding skills who work in an area steel mill or shipbuilding business; some welders have fashioned beer barrels into fish boil kettles (Fig. 4), and others have started with stainless steel Speed Queen wash tubs (Fig. 5).

Display large image of Figure 2

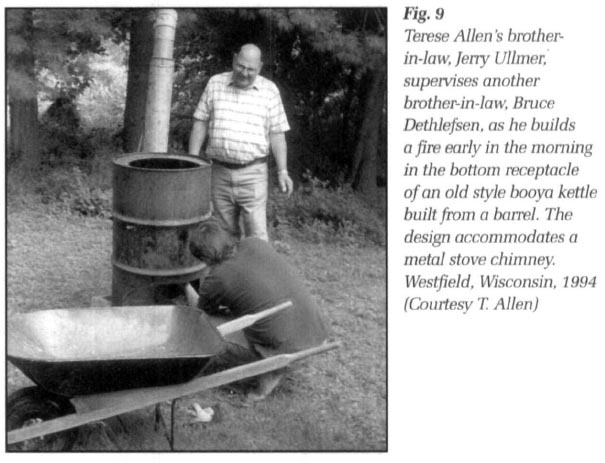

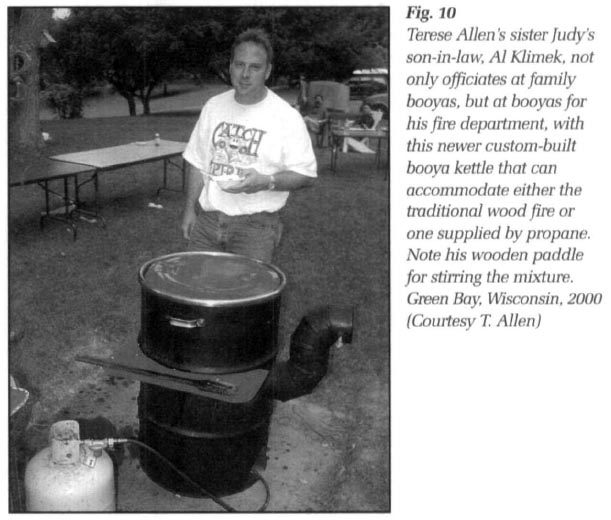

Display large image of Figure 2 Display large image of Figure 3

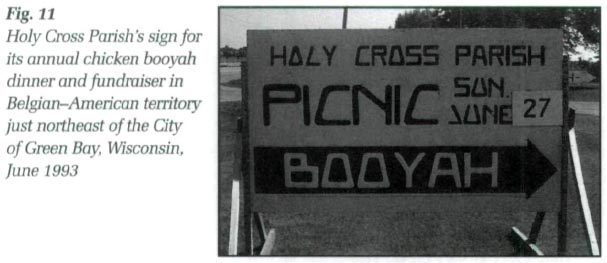

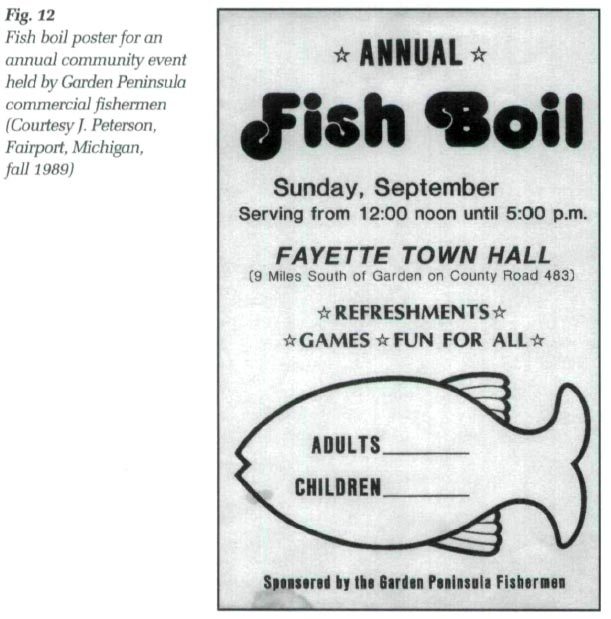

Display large image of Figure 3 Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4 Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 55 In the 1960s, in Door County, the preparation of this dish became a public event, and the boil-over flare-up a bit of public theatre. Since then the fish boil has become an important symbol of regional identity for Door County and Wisconsin, and it has spread widely throughout the state and region. Before it "went public," however, it was a dish associated particularly with commercial fishing families around the bay — not just Door County — who might feature an outdoor boil during the summer for a gathering of friends. Or they might cook the meal at home on the stove in a special commercially-made Leyse brand kettle when friends visited.6 Or when the weather was nice while they were out fishing in gillnet tugs, they might boil a freshly-caught fish in a pail or pot on the boat and share it with other fishermen working nearby. Commercial fisherman Charlie Nylund of Menominee-Marinette generally keeps onions and potatoes on his fish tug, which he will boil with a whitefish every day or two during the season on the two-burner bottled-gas cookstove he keeps on board.7

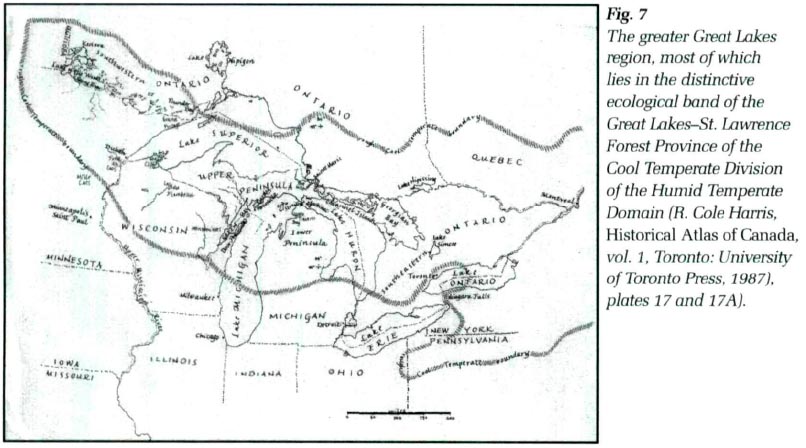

6 Hearsay attributes the dish to Scandinavian fishermen and sometimes logging camp fare,8 but the Green Bay area in Wisconsin and Michigan is diverse in its ethnic make-up, and most of the groups — whether descended from indigenous groups, like Menominees and Ojibwas, or Europeans like French, Belgian, German, Czech and Bohemian, English, numerous Scandinavian groups, and more — harbour boiled fish recipes.9 Notably, however, boiling chunks of lake trout and whitefish without much in the way of seasoning or other ingredients was a common meal for the western Great Lakes fishing Indians, Ojibwas, Odawas, and Hurons especially.10 At the time of European contact, these groups clustered to fish during the summer and fall at key spots along the shores of northern Lake Michigan, southern Lake Superior, and northeastern Lake Huron, an area centred roughly around Sault Ste Marie, where the easternmost Upper Peninsula of Michigan meets Ontario (Fig. 7).11

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 6 Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 77 While I was interviewing western shore fishing people about their fish foodways, I also encountered a similar dish with a similar name, "fish booya." In fact one old-time fisherman, the late Hector Peterson of Michigan's Garden Peninsula, used the terms fish boil and fish booya interchangeably.12 But Lyle Thill, a slightly younger man who lived up the road from Peterson, pointedly distinguished a fish boil from a fish booya, associating the boil more with the Door County area across the bay, "where they cook the whole potato and the whole onion."13 Similarly prepared in another type of custom kettle (Fig. 8), when fish was readily available, and as an excuse to share and gather, the fish booya is more like a soup than the fish boil. A wider range of vegetables is chopped and added, fish is cut up finer, and the broth is served and consumed with the cooked vegetables and fish.

8 For his fish booya feeds, Thill chunks onions, potatoes, carrots, and celery — "cut 'em up like in inch [2.5 cm] squares...everything is kind of chunked up" — and he uses skinned, boned white-fish fillets about twenty centimetres long where "you make about four pieces out of each side of the fillet." Since he prefers a booya that's "not real juicy and...not real thick," he uses "about the same amount of water as you got in the amount offish and vegetables." So, "if you got 20 pounds [9 kg] of fish, and say maybe 8 pounds [4 kg] of potatoes, and 6 pounds [3 kg] of carrots... say 5 quarts [5 L] or 10 quarts [10 L] full, well you'd put ten quarts [10 L] of water." To prepare the booya, Thill says:

Thill seasons the mixture with salt and pepper, and when he puts in the onions and celery, he adds "a lot of good butter.. .say like for ten gallons [45 L] I'd use a pound [500 g] of butter." He built his propane-fired kettle, which he loans out just about "every weekend" so that when he wants to use it himself, sometimes he has to fetch it.

9 The Door Peninsula of Wisconsin is also home to a chicken booya (also referred to as "booyah." "bouyon") tradition, practiced particularly among descendants of Walloons, French-speaking southern Belgian immigrants who came to the area in the mid-nineteenth century and claim booyah as their special dish.14 Recipes for chicken booya are similar to fish booya: a varying wide range of chopped vegetables along with stewed chicken (or other meat), prepared in a custom-built, outdoor, wood-fired kettle (Figs. 9 and 10). Like a New England "succotash,"15 a "Brunswick stew," a "mulligan," a "Kentucky burgoo," and even "turtle soup" found elsewhere in the United States, it is a catch-all, "everything but the kitchen sink," type recipe that varies widely according to what is available, and the preferences and habits of the cooks. Wisconsin culinary writer Terese Allen, of this Green Bay area Belgian stock, writes:

Like the fish booya, neither onions or chicken, or other meat, are sautéed first before water is added; they are simply cooked in the concoction's water. Unlike the fish booya, however, the Belgian-American booyah cooks a long time, it can sometimes be quite thick and stew-like, and some Belgian descendants use noodles instead of potatoes. Twin Cities booya makers refer to the consistency of the final product as "just mush;" Terese Allen qualifies that the Green Bay type mixture is still soup-like, but the solids will have disintegrated into almost indistinguishable mushiness.17

10 Apart from differences in ingredients and preparation, boils and booyas are perceived as fairly simple, easy-to-make one-pot meals. They often are cooked outdoors, often by men. in special kettles that often are custom-built and vary according to the specific type of boiled dinner as well as the particular social context. Generally these meals are prepared for gatherings of family, friends, and neighbours, privately at homes, reunions, in recreational and occupational settings like on fish tugs and at fall-time hunting camps, as well as in more public settings like church fundraisers and community festivals18 (Figs. 11 and 12).

Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 8 Display large image of Figure 9

Display large image of Figure 9 Display large image of Figure 10

Display large image of Figure 10 Display large image of Figure 11

Display large image of Figure 11 Display large image of Figure 12

Display large image of Figure 1211 When I began to develop my original fish foodways report to the Michigan Traditional Arts Program for publication, I attempted to place the foodways traditions in a greater historical context. While most of the people I had interviewed were not First Nations people, a few did have Ojibwa or Odawa ancestors. I wondered about the participation of the area's indigenous population in fishing and what record there might be of the manner in which they prepared fish to eat.

12 The writings of adventurers and missionaries who explored the western Great Lakes region during the early contact period in fact bear interesting observations about the importance of fishing to the region's inhabitants, and the importance of fish in the diet. Based on these historical records as well as archeological findings, geographer Erhard Rostlund characterized these fishing people as some of the most extraordinary fishermen in North America prior to the contact period,19 and archeologist Charles Cleland has convincingly argued that big-bodied fish caught offshore by gillnets in the fall, dried and frozen for winter use, was the chief way that the indigenous inhabitants could survive in the northwestern Great Lakes region.20 Even as recently as the second decade of the 1900s, anthropologist Alanson Skinner gathered that, during the early contact period, the Menominee people, who lived at the base of Green Bay and depended heavily on giant sturgeon for their livelihoods, were "almost maritime," he said, adding, "It was essentially a culture of wild rice, fish, and lake products."21

13 Writers from the early contact period, and ethnographers later on, suggest that at one time there was a complex and sophisticated culinary repertoire that surrounded fish preparation and preservation. Fish were boiled, roasted, and dried in varied ways, whole and in parts, and most parts, including bones, were also prepared and consumed, so that little of the fish was wasted.22 Baron de Lahontan noted the zest that western Great Lakes area Indians had for fish broth in particular—and he did not understand the enthusiasm for fish broth over broth made with meat.23 Some sources mentioned that sometimes the fish was removed from the broth and sittings of corn were added to make a generally watery soup or mush. Others mention dishes where fish would be boiled until it disintegrated and then joined with another mixture of corn siftings similarly boiled to varying consistencies. Besides fresh fish, dried fish, which was generally pulverized, or fish oil might be added to this "corn gruel" base. And instead of fish, some accounts say that meat and/or berries, often dried, might be added to the corn gruel.24

14 Le frère Gabriel Sagard Théodat, living among Huron Indians inland from the eastern shore of Lake Huron in the early 1600s, provides one of the most detailed accounts of the varied methods of preparing corn, in particular, and especially as the base for this boiled "gruel."25 Fresh corn might be roasted first in the fire, dried further, stored, and then boiled whole:

Or it might be dried without roasting first, then roasted, crushed and the siftings used:

Or the corn might be simply dried, then crushed, and the siftings used:

15 Sagard refers to this family of boiled dried corn foundations as "la Sagamité" (capitalized in seventeenth-century France). From some of their earliest writings during the first decades of the seventeenth century, French-speaking Jesuit missionaries and French-speaking explorer-writers use this term Sagamité, applying it to a major food item that they encountered as they travelled and mingled with varied Indian groups along the St Lawrence, through the Great Lakes, and down the Mississippi River. Perhaps obtained from an Abenaki term sôgmôipi, translated as "the repast of a chief," it bears a resemblance to the words we now know as "samp," and "succotash," which English speakers used to describe similar mixtures that the French called "Sagamité."26

16 Like the fish boil and fish booya, sagamité is portrayed in its most elaborate articulations as a feast food, from Abenaki territory to the northeast to the Upper Mississippi River area of what are now Illinois and Iowa.27 While the exact combinations of the dish changed with events and circumstances, and while native designations for it varied, the French missionaries and explorers carried the term with them and applied it fairly consistently to varied groups and situations where they found it.

17 At least a hundred years of initial French exploration and observation of the coastal areas off the St Lawrence predated the arrival of Jesuit missionaries and others who began to write down their experiences. By the most reliable Jesuit writings of Jean de Brébeuf in the early 1600s, the term Sagamité appears as a word already coined as a French version of, most likely, an Algonquian, or possibly, an Iroquoian term.28 The earlier writings by French missionaries tend to explain what the mixture they call Sagamité is, whereas later ones tend to refer to it as an already well-known concept. Says Paul Le Jeune, writing about his adventures in 1633 near Quebec City:

Writing in 1636, Brébeuf iterates the many discomforts that await prospective missionaries, including cramped, uncomfortable conditions in bark canoes that are upset or dashed on rocks fifty times a day, sunburns, mosquitoes, only the earth and sometimes rocks for a bed, only the stars for a roof, silence, no assistance if one is hurt or sick, "and in the evening, the only refreshment is a little corn crushed between two stones and cooked [cuit] in fine clear water."30 Within the next year, he had formalized his cautionary complaints into "Instructions for the Fathers of Our Society Who Shall be Sent to the Hurons," which read rather like a contemporary guide to preparing a backpacking or mountain climbing expedition crossed with advice for gaining rapport in a distinctly different cultural context. Here he cautioned, "You should try to eat their sagamité [sagamitez] or salmagundi [salmigondits] in the way they prepare it, although it may be dirty [sales], half-cooked [demi cuites], and very tasteless [tres-insipides].'31

18 One of the keys to Jesuit survival on these trips was dried Indian corn which the emissaries could obtain in the New World instead of transporting volumes of their own grains and flour from Europe, and, like their Indian hosts, carry with them and use to make a simple meal of crushed dried corn and boiled water, mixed with other tidbits as they became available.32 As in booya, in sagamité we have a boiled, one-pot meal, with flexible ingredients (a "salmigondits": "hotchpotch" or "medley"; see note 31), something that can be made very simply as basic, everyday fare — "tres-insipide:" "very tasteless, dull, or flat" — and something that can be dressed up to be a feast food. Among Jesuits and Indians travelling, it was a basic survival dish prepared outdoors by men, sometimes rather elementally, just like a fish boil in a pail among commercial fishermen on their fish tugs, or like a booya prepared as a hunting camp meal. In a village community setting, where there were ampler stores of ingredients, a more full, more sophisticated range of utensils, a greater workforce, and the licence to take more preparation-time, it appeared as a more elaborate mixture, more often made by women, as everyday fare as well as for celebratory purposes and larger gatherings.

19 Jesuit descriptions regularly associate the preparation with cooking in water, using the verb cuire (to cook) with l'eau (water, especially noted as clear, claire) to mean "to boil" in the sense of producing a clear broth, but perhaps just as often employing some version of the verb bouillir (to boil), particularly as an adjective in past perfect tense or a noun [bouillie, bouillon: broth). François Le Mercier reported in his "Relation of 1667-68," while dining among Iroquois of Agnié, "... le festin, qui consistait à un plat de bouillie de bled d'Inde cuit à l'eau...avec un peu de poisson boucané, et pour dessert un panier de citrouilles. "33 In this context, "booya" could easily replace bouillie: the two terms match well in terms of usage and meaning, structure and function, and sound.

20 Reporting from, perhaps, the western edge of the culinary tradition's regional range, Anne Kaplan questions a legendary French-Canadian connection to "booya," both the term and the dish.34 Yet the first volume of the Dictionary of American Regional English supports the term's derivation from French via Canadian French.35 I suspect that seventeenth-century culinary words and meanings based on bouillir possibly represent both cooking methods and one or more distinctive kinds of meals that were well known by the various French people who explored and settled the Great Lakes region and applied the term to similarly prepared dishes they encountered among native peoples and other immigrant groups.36

21 Members of the audience who heard the first version of this presentation reported numerous, mostly Canadian, contemporary boiled food traditions and terms that resemble one or more of the Green Bay area meals described above.37 The most striking associations come from the work of Marielle Cormier-Boudreau and Melvin Gallant in researching Canadian Acadian foodways among descendants of French emigrants who began settling in eastern Canada and, after a period of English-imposed exile, reconvened in Canada's Maritimes from different locations. Cormier-Boudreau and Gallant claim that the original immigrants left west central areas of France during the seventeenth century.38 In spite of the exile period, they discern continuity in Acadian foodways from the early settlement period into the present.39 While further research of various types is clearly necessary, elements of contemporary Acadian foodways bear distinctive similarities to the Green Bay area boiled meal traditions, whether ancient, indigenous, immigrant, or more recent.

22 From the descriptions of the Green Bay fish and chicken booya traditions that I explained to her at the 2002 meeting of the Folklore Studies Association of Canada/Association canadienne d'ethnologie et de folklore in Sudbury, Ontario, Cormier-Boudreau likened them most to the popular contemporary fricot, like Acadian cookery in general, an "uncomplicated," "straightforward," meal "prepared using just one pot."40 Referring to the dish as one that can be called typically Acadian, she and Gallant describe the fricot as "a soup containing potatoes and meat, fish or seafood";41 from the recipes provided in A Taste of Acadie, onions should be added to that list. Upon closer inspection of the recipes provided in the "Fricot" section of the cookbook, all call for the onions and potatoes to be diced, the onions sautéed, and any meat or fowl sautéed or browned.42 However, the authors note four basic fricot-making variants, two of which, Methods 2 and 3, do not involve any sautéeing of ingredients. One of these, Method 3, they call "the most widespread in southeastern New Brunswick," and it "differs from the others in that the meat is cooked whole," with the meat simmered in boiling water with the other ingredients, and the bones removed when the meat is well-cooked.43

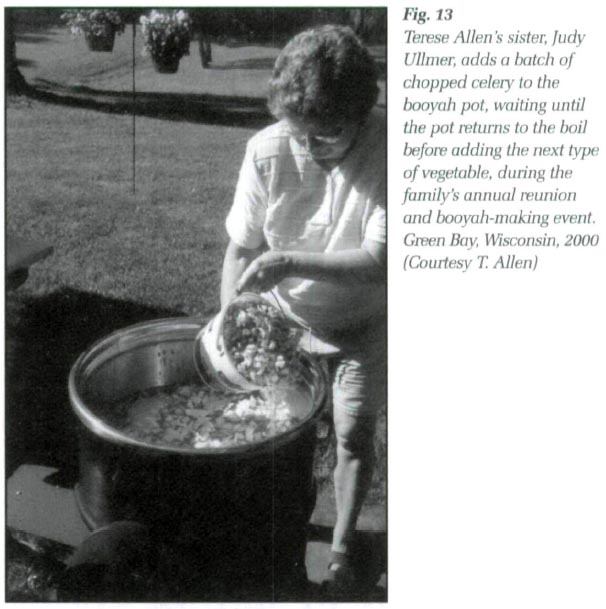

Display large image of Figure 13

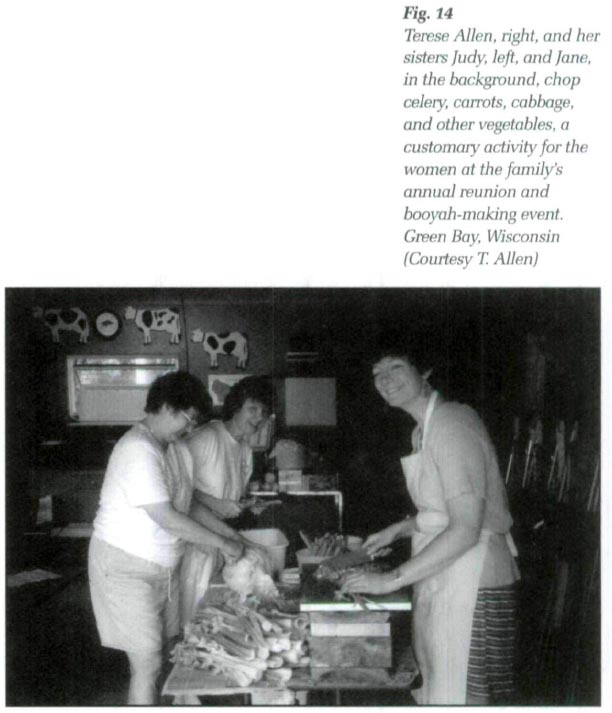

Display large image of Figure 13 Display large image of Figure 14

Display large image of Figure 1423 The cooking technique of the Method 3 fricot resembles some western Great Lakes Ojibwa and Menominee treatments of fish before corn is added to the mix, but it matches more closely the Belgian-American booyah tradition of Green Bay, as well as the Twin Cities variety, with the meat boiled whole, then removed when cooked, the bones extracted, and the meat added back to the pot, and then the vegetables group by group, longer-cooking varieties first, Green Bay style (Fig. 13). Like the Green Bay booyas and many of the Algonquian and Iroquoian dishes, but unlike the fish boil, the ingredients are also chopped (Fig. 14). But the simplicity of fricot ingredients matches that of the Door County fish boil and resembles the Indian approach to sagamité or cooking fish, while for the Green Bay booyah the range of vegetables is insufficiently diverse. Among some Acadians, however, there also are traditional recipes for soupe de petit jardin, also called soupe de devant de porte and soupe varte, that includes a more varied range of in-season garden vegetables that are common to the Green Bay and Twin Cities booya pot.44

24 One could argue that common to the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century heritage of French-speaking Acadian and Walloon immigrants to eastern Canada and the Great Lakes were fricot-type meals and cooking techniques that were equally encouraged by cooking techniques encountered wherever they settled. In both cases, these settlers may have met syncretic versions of one-pot boiled meals appropriate to the nomadic habits of French fur traders, missionaries, explorers, and fellow Indian guides. The Wisconsin setting, with its slightly longer growing season and greater diversity of garden vegetables than in the Canadian Maritimes, may have encouraged preparation of a special soupe de petit jardin version of a simpler everyday boiled meal, especially during the celebratory end-of-summer Kermiss harvest festivals of Wisconsin's Belgian-Americans.45

25 Equally suggestive to commonalities between Acadian fricots and Green Bay booyas, is the common use of versions of the term bouillir for the names of numerous Acadian dishes, including fricots. Cormier-Boudreau and Gallant mention, "In western New Brunswick, fricot and bouillon (broth) are the same, whether the main ingredient is meat or fish."46 In Taste of Acadie, several recipe names include the telltale word bouilli: poisson bouilli (poached fish), morue "sec" bouillie (boiled dried cod), houmârd bouilli (boiled lobster), and blé d'Inde bouilli (boiled corn), even poutines bouillies (boiled pudding), and glaçage Inuilli (boiled icing); as well as bouillotte à la morue fraîche (fresh cod and potatoes), bouilli à la viande salée (boiled salted meat), bouilli au boeuf (boiled beef), and la bouillie au blé d'Inde lessivé (hominy-style corn soup).47 In part, the recipes with bouilli- in their names represent a method of cooking the foodstuff by boiling, where the boiled water would not be consumed, as in the fish boil — which has the same linguistic construction, only in English. Of the fish/shellfish recipes, only the bouillotte contains potatoes, and only with the boiled beef recipes is there a more varied range of vegetables, offered whole or in large chunks as in a New England boiled dinner. The authors emphasize, however, a familiarly strong preference for simple fish cooking techniques: "In most instances, fish is simmered in water with salted herbs, salt and pepper. In fact, it was commonly believed that fancy sauces and complicated preparations served only to mask fish of dubious taste and quality."48 And in discussing la bouillie au blé d'Inde lessivé, they note that "Bouillie is a thick soup with a milk and hominy-style corn stock added to either salt pork or ham hocks." They add "Bouillie simple (Simple Soup) may be made by adding the hulled corn and a small amount of sugar to a thick white sauce made with milk."49 Barring the milk, and imagining the pork as exchangeable with dried or smoked fish, this recipe suggests the debt to Indian heritage and the pervasiveness in the past of the sagamité family of preparations. Could the thick sagamité type one-pot meals have also inspired the western Great Lakes' booyas that cook to a merged mushiness?

26 OK, I've thrown about as many ingredients into this pot as one might find in a Green Bay booyah, with a resulting mushy consistency that will require considerable extra sleuthing to figure out. But in attempting to identify individual contributions and their effects on the overall "dish," I propose, in ending: the writings of French missionaries and explorers had a definitive effect on shaping what the outside world could see and know of First Nations foodways from the early contact period. They applied a Native American-based designation, "sagamité," to a family of indigenous concoctions that had a much more varied range of terminology, processes, and conceptual relationships within and across specific First Nations peoples, legitimating the native cuisine while simultaneously homogenizing and reducing it to a single concept. They also used their own common terms like un bouillie to describe the foods and preparations that they experienced among First Nations peoples, likening them to what may have been commonly known culinary terms and dishes in their seventeenth-century home environments.50 These terms and concepts also happened to serve them well in the new unsettled setting. Application of bouillie, term and concept, has especially persisted, perhaps displacing sagamité, term and concept, as French immigrants adopted First Nations cooking techniques for corn, tailored corn dishes to their own culinary tastes, and matched them with similar one-pot boiled meal concepts from their own foodways traditions. Bouilli(e) has remained a useful term among Acadian Canadians to designate a range of customary dishes as well as specific customary cooking techniques, but the almost synonymous word fricot appears to be displacing it, referring more pointedly toward preparations identified with Acadian Canadian culinary identity. Bouilli(e)'s relatives booya, booyah, bouyon, and even boil in the western Great Lakes area, especially around Lake Michigan's Green Bay and a stretch of northern Wisconsin territory reaching west and north of Minnesota's Twin Cities, have come to denote a fairly limited repertoire of festive preparations, for the most part losing clear links to the French language or a broader boiled dinner culinary concept. These French-derived names, and simple, one-pot boiled dinner traditions with uncanny similarities survive among Canada's Acadians, the Green Bay region's culturally plural residents, and some First Nations people, where they have become important regional, ethnic, occupational, and working class markers, often identified with particular groups like Acadians, Belgian-Americans, Catholics, commercial fishermen, Scandinavian-Americans, as well as Woodland Indians engaged in the powwow scene.

27 The contemporary dishes in name most strongly reflect French linguistic, culinary, and perceptual influence of the early contact period, but their compositions, preparations, and presentations reveal the effects of cultural pluralism, syncretism, and commonality across a much greater range of cultural groups who share history and the common nature of a particular ecological zone. Among these groups, it is especially important to include the broader region's indigenous peoples, especially in the Green Bay and Upper Peninsula area, the former nexus of the fishing Indian domain, where fish in many forms was once an important ingredient in the one-pot boiled meal.

I am grateful to the generosity of Terese Allen, Doug Hadley, Nicki Saylor, and Stacy Grahn in helping assemble and prepare images for this publication.