Articles

"Traces of Coming and Going":

The Contemporary Creation of Inuksuit on the Avalon Peninsula

Abstract

Around the city of St John's, Newfoundland, the construction of inuksuit (stacks of rocks, often in the form of a person) is a popular pastime for visitors to outdoor sites, as evidenced by the abundance of these figures along walking trails and hiking trails, on beaches, and at campgrounds. Meredith Wilson and Bruno David, in the introduction to their compilation of essays entitled Inscribed Landscapes, state that they feel a multiplicity of meanings, common in artistic cultural productions, is especially prevalent in rock art* due to the many layers of communication that are present: natural landscapes, sociocultural influences, and artistic representation. This paper will explore the creation and uses of inuksuit in this contemporary context, and will attempt to unravel their meaning within the contexts of landscape, place-making, and cultural borrowing.

Résumé

Autour de la ville de St. John's, à Terre-Neuve, la construction d'inukshuks (empilages de pierres prenant souvent la forme d'une personne) est l'un des passe-temps favoris des visiteurs des sites en plein air, comme le démontre l'abondance de ces silhouettes qui peuplent les sentiers de promenade et de randonnée, les plages et les terrains de camping. Meredith Wilson et Bruno David, dans l'introduction de leur compilation de textes intitulée Inscribed Landscapes, expliquent que la multiplicité de significations, une particularité commune aux œuvres culturelles artistiques, est particulièrement dominante dans l'art rupestre*, étant donné les nombreuses strates de communication qui existent dans le paysage naturel, les influences socioculturelles et la représentation artistique. Cet article étudie la création et l'utilisation desinukshuks dans le contexte actuel et tente de révéler la signification de ces œuvres en tenant compte de facteurs tels que le paysage, la création d'un lieu défini et l'emprunt culturel.

Introduction

1 Trying to describe inuksuit (the plural of inuksuk) can be difficult, because the more one learns about them, the more one realizes how they are both simple and complex. They utilize the most basic of materials and human skills, and yet possess a timeless presence that even the most unknowledgeable observer can sense. The best way to become familiar with these objects is through people's descriptions of them and their experiences with them; this paper will present several informal descriptions, like the above one from a student who lived in the Arctic for several months, and several more academic explanations as well. Both voices are necessary to convey the scope of this kind of creation.

2 The word inuksuk (correctly pronounced "inook-shook" and alternately spelled "inukshuk") is Inuit for "to act in the capacity of a human being,"2 and refers, at the most basic level, to stacks of rocks constructed in natural spaces. Their most typical action in the capacity of an absent human is to mark a location or to point the way to a location; their construction often incorporates a component used for directionality. They are found all over the Arctic regions — Alaska, Canada, and Greenland3 —and have been used by the Inuit for thousands of years.

3 Inuksuit are always made of at least two or more rocks, usually rocks that are available in the immediate vicinity of the builder at the time of construction, and they are always stacked in some way that requires the rocks to balance. Technically, an inuksuk can be any balanced stack of rocks that catches a traveler's eye — Inuit elder Jerry Sillitt explains that "an inuksuk can be made any way at all, according to personal taste, as long as it can be easily seen from a distance and can be identified as an artificial construction"4 — but during my field work I encountered a general concern with issues of authenticity of form. This is an issue that will be explored more in depth later, but suffice it to say for now that several of my informants seemed to be concerned with the "right" way to build an inuksuk. One noted: "I don't really think what we created actually even resembled a real inuksuk."5 Another described her sense that certain inuksuit on the road were "really real ones," implying that others may not be.

4 There are no size requirements for inuksuit, though it is the larger ones that most often manage to withstand the test of time. Smaller inuksuit can be transitory creations, subject to the elements, although the resulting spread of fallen rocks still meets the requirement of being recognizable as a human-made construction. Larger inuksuit can be so long-standing that they become permanent facets of the environment, as evidenced in the following narrative by an Inuit Anglican priest, in which he describes a journey he took with a friend:

An inuksuk large enough that it can't be moved is an impressive construction; but whether large or small, all inuksuit are beguiling in their very palpable sense of purpose. They blend so well into their natural surroundings that their delicate balance is almost uncanny.

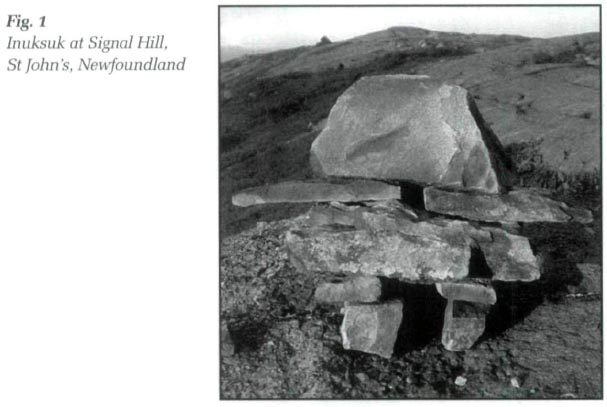

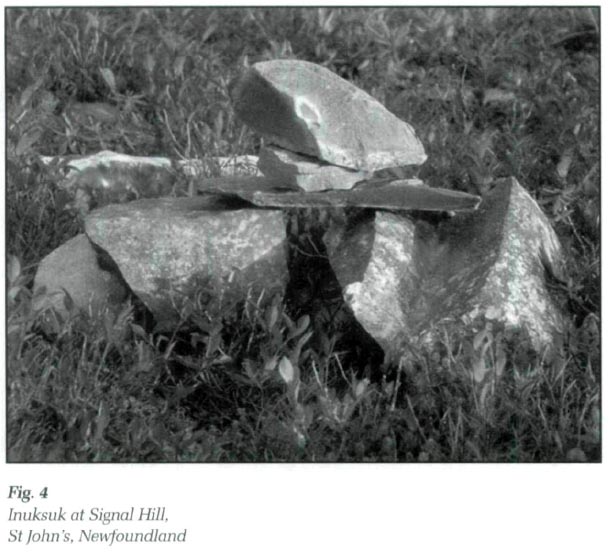

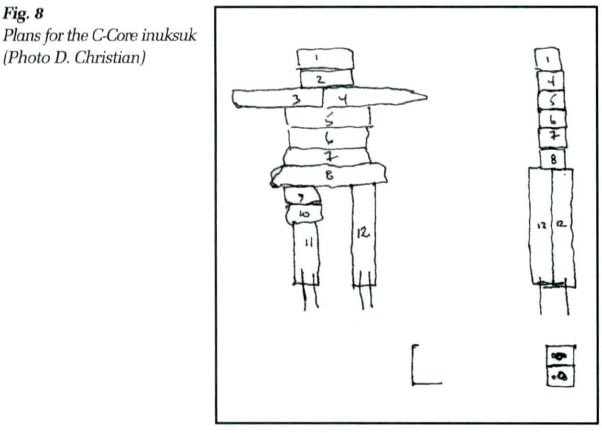

5 While earlier inuksuit had no required shape, contemporary versions, at least the ones that can be found in and around St John's, Newfoundland, tend to take the form of a person, a design that the Inuit call inunngiiaq. Some Inuit people feel that inuksuit were never made in this style before the first non-Inuit whalers arrived in the Arctic, while others claim that such structures have been in existence for several hundred years.7 Regardless of how long this design has been in practice, it is certainly a popular form for contemporary builders on the Avalon Peninsula. In the examples I have seen, there are at least five, usually six, rocks required for a person-shaped inuksuk: two for the legs, one for the body, one long stone or two shorter ones for arms, and one for a head. More stones can be added at any point to increase size or stability (see Fig. 1 — roughly half a metre tall — from St John's, Newfoundland, and as a comparison, Fig. 2 — a few metres tall — from Vancouver, British Columbia, for two vastly different sized inunnguaq). The person-shaped design seems b ) have influenced the construction of non-human shaped inuksuit as well, with regard to the creation of legs; basic cairn-like rock stacks (see Fig. 3) are often elaborated on to create an initial arch that then supports the basic stack (see Figs. 4 and 5). The Inuit describe a particular kind of inuksuit, a niugvaliruluit, that features a sighting hole8 — an opening in the structure that draws a viewer's attention to an important place or object—but the contemporary creation of archways appears to be a more aesthetic choice than a functional one. Another aesthetic choice seems to be the preference for delicate, single stacks over more heavy, pile-style stacks.

6 Around the city of St John's, the construction of inuksuit is a popular pastime for visitors to outdoor sites, as evidenced by the abundance of these figures along walking trails and hiking trails, on beaches, and at campgrounds. I first encountered inuksuit in a natural setting during a visit to Signal Hill, and was intrigued to witness the appropriation of this enigmatic object; I was fairly certain, after having spoken to several non-Inuit people who had created inuksuit, that the majority of these objects were not being constructed by Inuit residents of St John's. What are these objects expressing? And what are they communicating back to their makers and to the audiences who encounter them?

7 In an essay on the term "artifact," Barbara Babcock notes that "the use and meaning of an artifact can change radically depending on the context in which it is placed and the perspective from which it is viewed."9 Asa Berger expresses a similar idea when he asserts that "texts, in a sense, do not exist, hut rather are entities that can be brought into being only by readers."10 (And here it is important to point out Henry Glassie's observation that texts are both "things made of words and things made of earthy bits."11) Keeping this in mind, inuksuit created by non-Inuit people on the Avalon Peninsula could conceivably have an entirely different manning than the ones created and viewed in the Arctic by the Inuit. Meredith Wilson and Bruno David, in the introduction to their compilation of essays entitled Inscribed Landscapes, state that they feel a multiplicity of meanings is especially prevalent in rock art research,12 due to the many layers of communication taking place: natural landscapes, sociocultural influences, and artistic representation. One of my informants spoke to this discrepancy in meaning, describing her experience at Gros Morne National Park: "There was no obvious Native American connection, yet there were about twenty small piles of rocks, placed in different styles and arrangements. We made our own little pile but I often think that people do this out of our 'sheep' nature... we all follow the one before us."13 What does motivate the construction of these objects in and around St John's? Wilson and David refer to these creations as products of the "humanization of landscapes" (vii). Is the non-native creation of inuksuit a genuine humanization of the landscape, or simply a "sheepish" mimicking of someone else's tradition? This paper will explore the creation and uses of inuksuit in this contemporary context, and will attempt to unravel their meaning within the contexts of landscape, place-making, and cultural borrowing.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2The Construction of Inuksuit — Contemporary Case Studies

8 Like creators within many vernacular traditions, people who build inuksuit are both following a learned pattern and expressing their unique creativity. A few people with whom I spoke suggested that there wasn't much to the experiences of building and encountering an inuksuk; one woman felt they were simply "kind of cute, and certainly photogenic."14 Others, however, expressed a much deeper connection to the objects. One of my informants, who described adding stones to existing inuksuit that she came across as well as constructing her own, indicated that there is a sense of companionability to the objects; they not only keep you company themselves, but "they remind you that other people have been where you are before, and that you're now connected to those people and share something with them. And when you put a stone where other people put stones, it's like you're contributing a part of your presence to something that stays behind when you leave."15 This sense of contribution is interesting; it suggests that the inuksuit are acting in the capacity of several people at once, embodying not a single being but the many who have come before. It also renders many inuksuit perpetually incomplete, works of art that are always in progress and never finished. People who contribute stones are both the audience and the artists for an ever-changing creation. This results in an interesting, temporally displaced yet physically connected community. The awareness that other people's hands have touched the stones yours have touched creates a deeper sense of companionability than the initial creation of a new object. The fact that every person's added stones must balance with the rest also draws on this underlying theme of community and connects well to this sense of group contribution.

9 These emotional responses often lead to or are tied to assumptions about inuksuit's religious significance to native populations. Apart from the basic meaning of "acting in the capacity of a human" and their general function as signposts, people have, over the years, attributed many different meanings and uses to these objects, some of which are more spiritual than utilitarian:

Keirsten, one of my informants who lived in the Arctic for several months, encountered similar dismissals of any possible spiritual significances of inuksuit:

Keirsten's perception, developed after having lived in an Inuit village, that there are no spiritual meanings for inuksuit, could stem from the reticence of the Inuit people when it comes to such matters, as evidenced by the preceding quote from Norman Hallendy, a researcher who has devoted much attention to inuksuit. Hallendy did eventually find that there are types of inuksuit that mark sacred, or even forbidden, places. This does not mean that Keirsten's perception is necessarily incorrect; there could easily be different traditions in different places. With the kinds of inuksuit found on the Avalon Peninsula and created by non-Inuit people — contexts of creation that are far removed from traditional Inuit situations — it is not difficult to see how such a representation of a person could come to embody a sense of spirit even without the presence of a commonly shared belief system. The borrowing of the form from an "exotic" culture alone could begin to explain people's expectations of religious significance.

10 Other reasons to build an inuksuk can be to represent accomplishment; if one has come to a place that is difficult to reach, leaving something that acknowledges that one has been here is an expression of pride. Norman Hallendy explains that inuksuit are one among many kinds of utirnigiit, "traces of coming and going," to the Inuit people. He found that their respect for things that represented and expressed the will of their ancestors was immense, and inuksuit were one of the most respected of these traces. While the people I spoke with did not indicate any awareness of such a tradition among the original creators of inuksuit, some did touch on this idea of not just marking places that would be important to others, but places that are important to oneself. One woman I spoke with, Heather, described her arrival on the Avalon Peninsula. She was moving here, and when she got her first view of her new home, her boyfriend stopped the car and they got out to take a closer look:

That sense of accomplishment was validated when another student described how she had driven into St John's shortly after Heather, and had seen the inuksuk still standing:

It is interesting to note that all of the people I spoke with who built inuksuit around St John's (though my field work was definitely not exhaustive) never mentioned the Inuit people. If they saw this as an appropriated tradition, they did not tell me about it. What I did get was a strong sense that inuksuit simply are what they are, non-culturally-specific expressions of a person's presence, objects that can hold an identity, a message, or an emotion, long after the maker had gone away.

11 The perspective was understandably different for the one informant I spoke with who had made inuksuit only with Inuit people while living in the Arctic. Keirsten, a graduate student at Memorial University, lived in the Arctic town of Whale Cove (or Tikirarjuaq as the Inuit call it), a native resettlement village in Nunavut, for six months while her mother taught in a local school. Keirsten, with the company of her Inuit friend Alan Boise, Whale Cove's garbage man, built an inuksuk for traditional Inuit purposes:

The inuksuk that Kiersten built was small, "maybe two feet [60 cm] tall, max, just a little pile of balanced rocks. It didn't have arms and legs or anything cool like that," but she definitely felt that it was in line with the appearance and purpose of traditional inuksuit. When I questioned her as to why she had never built an inuksuk since returning from the Arctic when she, more than many others, had a closer connection to the "real" tradition, she expressed discomfort at the idea of building them anywhere else:

Unlike those who have built inuksuit only in non-Inuit contexts and who see the objects as very symbolic, Keirsten views them as completely utilitarian.

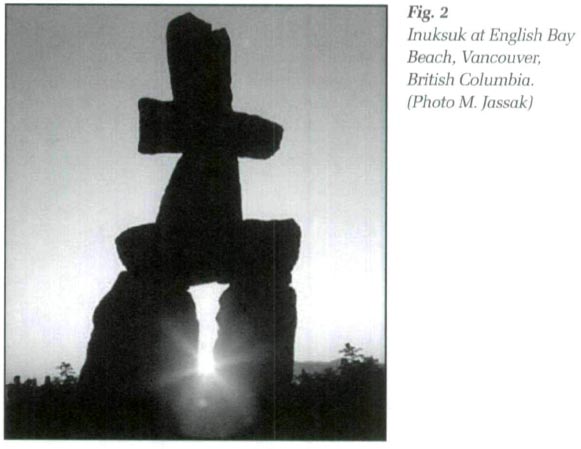

Display large image of Figure 6

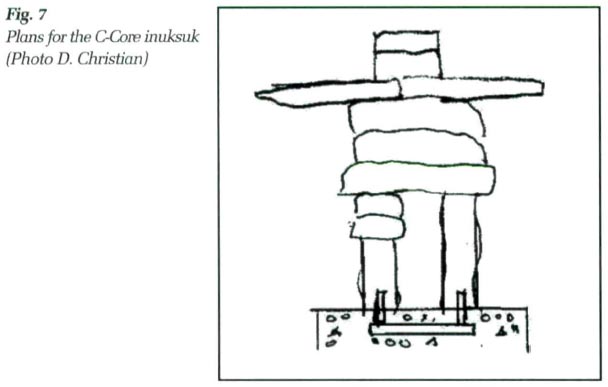

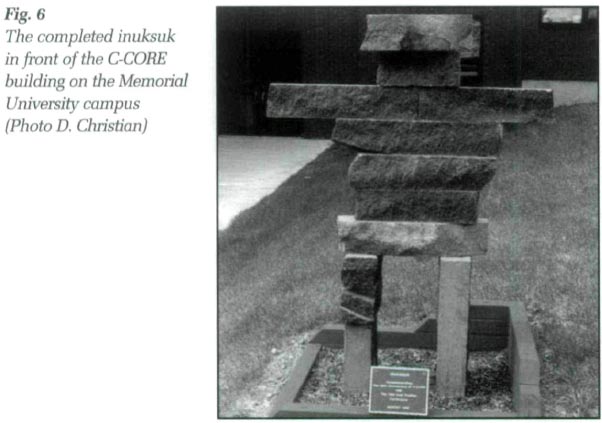

Display large image of Figure 612 Another interesting inuksuk case study — one that is totally symbolic and quite official — is the inuksuk that stands outside the Bartlett building on the campus of Memorial University (Fig. 6). The Bartlett building houses C-Core, an engineering research and development company, whose twentieth anniversary fell on the same year that C-Core sponsored an Inuit studies conference on the Memorial University campus. To commemorate both the events, Jack Clark, president and CEO of C-Core at that time, suggested that an inuksuk be built outside the building. Denny Christian, C-Core's director of technical support and logistics, was asked to build the inuksuk, and began the task with thorough research, knowing it was a serious object that he would be creating. He wanted to make the inuksuk as authentic as possible:

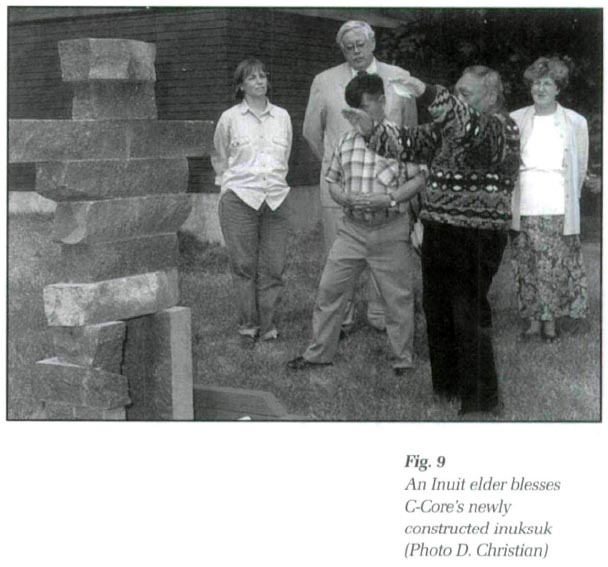

While all efforts were made to be authentic, some"cheating" (as Denny put it) could not be helped. They cut the granite to the right size, rather than leaving it as they "found" it, and they fastened the pieces together with bolts, to ensure that it would withstand environmental pressures. C-Core's inuksuk is roughly one and a half metres tall and is constructed of twelve separate pieces of stone. Denny and his student assistants planned their inuksuk carefully (see Figs. 7 and 8 for Denny's designs), and even invited Inuit students to be a part of its creation. According to Denny the students weren't too excited, though C-Core did end up getting an impressive spiritual endorsement from an unexpected source:

While this inuksuk is not a personal informal creation, it is definitely a symbolic one more than a utilitarian one.

13 From just the above few examples, it is plain that the ways in which inuksuit are built and the things they communicate are quite varied. Is it possible that such diverse purposes and significances can come together to create cohesive meaning in this type of object? I feel that despite the individual contexts of creation, the unique responses to the objects, and the diversity of experience with them, there is a consistent message being expressed, at least at the most basic level of representation.

The Creation of Place in Space

14 The noted philosopher and geographer Yi Fu Tuan has discussed the distinction between "place" and "space." As he described, "Place is a special kind of object. It is a concretion of value, though not a valued thing that can be handled or carried about easily; it is an object in which one can dwell."24 Space, on the other hand, "can be variously experienced as the relative location of objects or places, as the distances and expanses that separate and link places, and—more abstractly— as the area defined by a network of places."25 So space, in Tuan's conception of it, is openness: it is disoriented and unfocused. In contrast, places are points of orientation, directions within the open expanses, familiar secure areas that give us a sense of our own place in things. Tuan observes that human beings need both space and place in which to exist (though he does note that some people, agoraphobes and claustrophobes, have trouble dealing with one or the other). Tuan describes human life as a movement back and forth between space and place, explaining that as people encounter spaces, they "humanize" them26 and create places.

15 In my opinion there is an intriguing correlation here to the dichotomy between nature and culture. Barbara Bender, in a discussion of landscapes, touches on this divide: "The way landscape came to be understood was part of a wider process of individuating people, of separating out people-culture and land-nature, and of asserting control over land-nature."27 Nature is wild and free; culture is controlled and contained. To connect this to Tuan's terminology, nature is space and culture is place. He says as much himself in his exploration of landscapes, Landscapes of Fear, when he notes that "every human construction — whether mental or material — is a component of a landscape of fear because it exists to contain chaos."28 Human constructions are products of culture — manipulations of nature — and provide secure "places" in the chaos of natural "space."

16 Mircea Eliade, in The Sacred and the Profane, makes the above distinction in terms of sacred versus profane space. Sacred space "ontologically founds the world,"29 creating points of reference and a much needed sense of orientation. Profane space is "homogeneous and neutral; no break qualitatively differentiates the parts of its mass." 30 Eliade describes how human beings are constantly creating "fixed points"31 in the space around them to fend off the profane and the chaotic. These fixed points are places, according to Tuan, and come into being when a person manipulates the natural environment and creates an object of culture.

17 While the categories of nature and culture do exist in opposition to each other, it can be more useful to think of it in terms of a spectrum, with some cultural creations being much farther in from nature, much more worked by humans, than others. A bookcase may be constructed out of wood, but the more the wood is treated and stained, and the more ornamentation that is applied to the basic design, the more culturally expressive the bookcase becomes. Similarly, when wood is shredded into sawdust and reconstituted with glue to create particle board, an object that is perhaps not as decorative or valued an art object as a handmade bookcase would be, it is still at the far cultural end of the spectrum, due the numerous levels of human interference that occur between the initial natural product and the resulting finished cultural object. It can be seen then, that inuksuit are at the far natural end of the nature-culture spectrum. They reflect the most basic level of a human's manipulation of nature.

Inuksuit as Cultural "Places"

18 Despite people's various uses of inuksuit and their varying levels of familiarity with the traditional origins of the objects, it seems apparent to me that they are being used in all cases as markers of orientation to create places within spaces, to differentiate the parts of the chaotic mass of nature. The traditional functions of marking good hunting grounds or well-stocked lakes on the monotonous landscape of the tundra make this assessment obvious. Tuan's description of the sensation of being lost in a natural space illustrates the idea more abstractly:

The light in the forest is the inuksuk, offering orientation and pointing the way out. The contemporary construction of inuksuit in and around St John's also speaks to the makers' needs to create order within chaos, to orient themselves and others along a defined path, albeit in a more subtle or figurative way. Returning to Asa Berger's observation that a text's meaning is created at least in part by its readers, it would be necessary for any inherent meaning in an inuksuk, if it is to be evident and effectively communicated to a wide audience, to be a message that the majority of viewers have the ability to decode.

19 With regard to the inuksuk's place as a culturally borrowed object, Tuan's ideas about the differences between "visitor" and "native" perceptions of environment, expressed in his work Topophilia, can help interpret the way in which inuksuit are decoded by a diverse audience. While the non-native people building inuksuit on the Avalon Peninsula are not necessarily visitors to the land, we can perhaps think of them as visitors to the inuksuk-bearing landscape. The general concern for getting the form "right," or for determining the difference between "real" inuksuit and presumably false ones, speaks to many people's sense of themselves as outsiders to the tradition. It is tempting, in the spirit of cultural respect, to say that only those peoples native to the tradition have a valid relationship with it or interpretation of it, but Tuan notes that in such instances, it is really "only the visitor (and particularly the tourist) [who] has a viewpoint"33 ; the native's perspective is too complex to be coherent, due to "his immersion in the totality of his environment."34 One point of view is simple; the other is complex. Add to this the fact that in both instances, in this particular case, both parties are not only audiences to the landscape but artisans as well. Tuan's assessment of perspective needs to be expanded to include interaction as well as viewing.

20 Belden Lane, in his study Landscapes of the Sacred, reflects on the fact that "Human beings are invariably driven to ground the irreligious experience in the palpable reality of space."35 I would argue that it is not only religious experiences that drive us to mark places within spaces. The mundane and the everyday, the basic fact of presence and existence, especially in places where nature and culture collide (which could arguably be anywhere in nature where people are even temporarily located), are expressed well through the creation of an inuksuk, a form which has the capacity to be small and unobtrusive as well as large and imposing. As Paul Taçon observes, all "landscapes" are a blend of natural features and cultural creations. The natural spaces that are most often noted or commemorated with cultural recognition (whether via a physical monument or simply intangible respect) are often "places where incredible change is emphasized or experienced—the boundary zones between forms of vegetation, rock, water, and sky."36 C. F. Blake discovered something similar, observing that graffiti, another form of place-marking, tends to appear in liminal places: bus seat backs, elevators, public toilets.37 It is hard to imagine a more impressive boundary zone than Newfoundland's Signal Hill, which brings land, sky, and water together in an impressive panorama. That quality of edge-ness is something that I feel is incorporated into Newfoundland's geographical identity, and makes this province a very appropriate place for the creation of inuksuit Knowing that the drive to create inuksuit is based in a multipart blend of natural and cultural forces, and knowing that those cultural forces can often be vastly divergent with regard to a borrowed tradition, is it possible for there to be any common denominator in the meaning of this object? As Wilson and David note, "the more informed the "receiver" of an image within the sociocultural milieu in which [an object] is found, the more likely the image will trigger recognition."38 Is there something in an inuksuk that enough people of diverse background can recognize, so as to make it such a successful cross-cultural signifier?

21 Folklorist Barre Toelken has referred to the development of audience realization as the process of "gleaning." His study focuses on a Chipewyan Athabascan word, the verb stem sas/-zas, which is used to describe "a dog gnawing a bone until it is clean, a woman picking berries, and someone listening to — and understanding—what another person is saying."39 While these actions may seem unrelated, Toelken notes that they "dramatize a set of cultural nuances"40 related to subsistence, and he feels the verb "gleaning" is the best English translation. When Toelken elaborates on the berry-picking example, he notes that the women are not simply picking berries; they know where to go to look for the berries, how best to gather them, and what not to pick: stems, leaves, and roots. When related to an audience listening or viewing, this implies that being an audience member is not a simple task, it is a proactive role that requires a complex and culturally learned system of realization. An audience must know what matters and what doesn't; cultural productions, from jokes to stage shows, may make no sense to a cultural outsider as much because that outsider doesn't know what isn't important as because he or she doesn't know what is. Any successful gleaning of a cultural product can only happen when the audience is prepared to identify and separate the berries and the twigs.

22 The inuksuit's presence at the most natural end of the nature-culture spectrum allows for their important identification—by a very broad range of people—as "artificial constructions"41 within a natural landscape; they do not have many other cultural constructions to compete with and therefore stand out. If one were sitting in a friend's living room and saw some rocks piled on the floor, the pile might look especially (and perhaps inappropriately) nature-ish in contrast to the highly cultured setting of a living room. If a cultural outsider were sitting in the living room however, he or she would first need to know what was considered "normal" for such a culture-dictated setting before being able to notice objects that stand out. But in the wild, in chaotic nature, rocks moved into an unnatural pattern — even when there has been no other significant manipulation of form or materials — stand out as cultured creations; the natural context highlights the slight and subtle intrusion of culture, making the least of efforts speak volumes. Brian Osborne has observed that "there is no inherent identity to places," and that understanding the meaning of a culturally constructed place "requires insights into people's traditional knowledge, cultural practice, forms of communication, and conventions for imagining place."42 This is undoubtedly the case for many complex cultural constructions, but one does not need a highly specific level of cultural learning to recognize this understated ordering of the normally disordered natural wilderness found in the inuksuk. Other place-creating practices, such as the traditional naming of particular natural locations, are abstract and require fluency and experience in a particular culture in order to function; the fact that a certain natural place is named is not apparent to a cultural outsider. In comparison, the level of comprehension required to recognize the human presence behind an inuksuk is shared by many people of diverse cultural background; many people are prepared to glean the necessary information. There are, of course, numerous other levels on which an inuksuk can communicate to people who do have more specialized cultural knowledge, but the meaning expressed by the basic form in its physical context is accessible to a wide majority.

Display large image of Figure 9

Display large image of Figure 923 So when a person creates an inuksuk, he or she is creating an easily recognized point of culture within a natural setting. Philospher Martin Heidegger has defined a "person" as a "being-there," espousing the philosophical opinion that a sense of place provides people with a much needed "existential foothold" in the world.43 The creation of an inuksuk allows us to be always "being there," perpetually keeping disorder at bay. It is important to note that this is accomplished while still respecting and working with, rather than against, the natural-ness of that setting: "the people who placed [the inuksuit] there were probably trying to use 'natural' type markers"44 to indicate their presence or show the way to a path. This desire to work with and match the environment emphasizes this tradition's location at the most natural end of the nature-culture spectrum; evidenced in an inuksuk's creation is the builder's effort to be as natural as possible while still getting his or her cultural message across. One could, as many do, simply paint one's name on a rock or carve one's name into a tree—both of which are also traditional ways of "signing the land"45 —but the building of inuksuit notably both deemphasizes the individual in favour of a sense of community (there are no names attached), and displays an appreciation for the environment, striving to disturb the natural context as little as possible while still orienting the space. The creation of inuk-suit in non-natural settings, such as in front of the Bartlett building, utilizes that sense of orientation and brings an awareness of the nature-culture dichotomy to a place it previously did not reside.

24 When describing inuksuit, some people often refer to themes of friendship and assistance, making the balanced rocks a metaphor for a balanced community where people rely on each other to survive: "When you see an inuksuk in the future, you will know they stand as symbols of the importance of friendship and remind us all of our dependence on one another."46 Though many people who make the inuksuit that are visible today on the Avalon Peninsula are not necessarily Arctic Inuit who rely on inuksuit to guide them for their survival, the power that comes with the creation of a place, a cultural point of reference tied to its maker, is something recognizable by a wide range of people. Whether creating a new inuksuk or adding a stone to an existing one, people are participating in one of the most basic and effective ways of communicating their humanity, and simply their presence, to the rest of the world.