Articles

The Study of Dress and Adornment as Social Positioning

Abstract

This paper examines the role of dress and adornment as a mode of social positioning, as a way to place individuals and communities firmly in history and geography. An analysis of the art of the body reveals various interpretations of time (personal, communal and historical) and space (gradations between public and private). The paper starts by providing a brief overview of multidisciplinary works on body art, supplying an intellectual context in which to conduct study. The argument of the paper is supported by data collected from close field work on body adornment among women in Banduras, India.

Résumé

Cet article se penche sur le rôle des vêtements et parures en tant que modes de positionnement social et manières de situer formellement des personnes et des collectivités dans un contexte historique et géographique. Une analyse de l’art corporel révèle diverses interprétations du temps (personnel, communautaire et historique) et de l’espace (gradations entre l’espace public et l’espace privé). L’article présente d’abord un bref aperçu des travaux multi-disciplinaires sur l’art corporel, indiquant dans quel contexte intellectuel mener l’étude. L’argumentation repose sur des données provenant d’observations sur le terrain des parures corporelles de femmes de Varanasi (Bénarès), en Inde.

1 The study of dress and adornment, along with various other manifestations of the art of the body,1 has experienced a surge of energy in the last few decades, as several scholars have noted, including Élise Dubuc in her editorial introduction to Material History Review’s autumn 2002 special issue on clothing.2 Dubuc rightly characterizes the new movement in scholarship as consisting of different perspectives, developed from various disciplines. Dress and textile historian Lou Taylor shares this opinion, expanding in her book, The Study of Dress History,3 on different methodologies. Although these scholars are correct in supporting an interdisciplinary approach that highlights diverse understandings of adornment forms and functions, most studies still maintain one central focus, based in the methods and theories of one discipline or another, be it fashion history, art history, history, sociology, anthropology, or folklore. Recent studies — the articles in the special issue of Material History Review, the works characterized in Taylor’s book, and especially the individual studies in the new series edited by Joanne Eicher, entitled Dress, Body, Culture — when taken together provide an overview of different approaches to the study of dress and adornment, but very few studies attempt a complete, fully integrated approach that unifies interdisciplinary methods in the examination of one area of the world.

2 The next goal for students of dress and adornment is to integrate the fine studies of body art into a variety of ethnographic analysis that will bring separate strategies of investigation together in a holistic examination. While it is necessary to divide adornment forms and functions, contexts and meanings into small units during the process of observation, documentation, and interpretation, in real life, form and function, contexts and meaning blend in simultaneity. Scholarship is divided by discipline, but on the ground, it all happens at once.

3 A major function of clothing and adornment is to position individuals and communities in space and time. Many works have looked at aspects of positioning, at ways of achieving historical or geographical grounding by deliberate manipulation of the presentation of the body. Though transdisciplinary unification is the goal, in the moment we must rely on excellent guides that examine segments of the functioning of body adornment, especially as it pertains to the notion of social positioning. I begin this paper by citing some notable works that further our understanding of forms, and especially of forms in the context of meaningful communication. After this concise look at the relevant scholarship, I will recombine the categories to illustrate how diffused perspectives can be incorporated in a coherent ethnographic study, as I describe women’s bodily presentation in contemporary India. My goal is to show how positioning, how intentional acts of self-situating, locate people at once in space, time, and society.

Literature Overview

4 One valuable way to understand the purposeful communicative positioning that people accomplish through their clothing is to look at their body art in relation to historical concepts. In fact, the basic social context inherent in most studies of clothing and culture is historical, a perspective in which interpretation is based on the examination of change and continuity in time and space. In surveying the movements in this scholarship, we discover history to be employed in six distinct ways, each one concentrating on some important dimension in the understanding of the acts and consequences of body adornment.

5 The first major category of historical study is one in which artifacts, and especially jewellery, are used to reconstruct the cultures of the past, such as that of ancient Egypt or pre-Columbian America.4 A second common approach is to use a vertical perspective, noting change over time, arranging costumes sequentially, and focusing on origin and evolution, the goal being to find relevant explanations and meanings in a historical sequence of creations. Many books on the history of costume and jewellery, the history of fashion, and the art history of clothing utilize this method.5 A third method is based on a horizontal perspective that locates variety in body art within a historical period, expanding the examination, not back in time, but rather outward spatially into society; the aim is to locate explanations within the current social context. This technique has been used effectively to analyse particular periods in the United States, for example, by examining the costumes of the diverse population of Colonial Williamsburg, or by considering the changes brought by the industries of ready-to-wear clothing and makeup in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.6

6 Three additional historical methods employed to study body art are centred on the contemporary. One approach is to attempt to understand some present-day item by tracing its historical development, a method employed by Valerie Steele in her engaging book on the corset.7 Another way in which scholars use the past to contextualize the present is found in studies of the revival of body art forms that had been abandoned, usually under colonial rule, such as Alfred Gell’s study of the resurgence of tattoo traditions in Polynesia.8 Finally, one last technique is dedicated to the methodical documentation of the present in order to capture completely one moment in time. This was the goal in the nineteenth century when outside observers made records of Native Americans, when Catlin made his paintings, Curtis took his photographs, and in more recent times, when ethnographers sought, through oral history, information on tattooing.9 Today such documentary efforts have also been devoted to street fashion in Tokyo10 and New York.11

7 The general concept of time can be further sub-divided. The temporal realm can be conceived of personally, as all human beings progress through certain life stages, culturally defined and differently conceived for each gender. Successful transitions between life stages are not only socially relevant, they are personally significant milestones, visually marked by a change in bodily presentation. Body art’s celebration of the life cycle is well handled in the scholarly literature. Many volumes, such as Foster and Johnson’s Wedding Dress Across Cultures, have focused on the most significant of these transitions — the wedding — and the beautiful and ornate clothing worn by the bride and groom.12 Other religious rituals for which specialized clothes are selected include baptisms, circumcision rites, communions, and lately, lavish bar mitzvahs and bat mitzvahs for which the honoured child wears expensive designer clothes. Many coming of age events contain elaborate dress customs, such as high school prom dances and cotillion events, both serving to transition adolescents into young adults.13

8 Explicit body art marks the rite of passage and carries the participant through a social transformation, and it indicates the permanent state entered from that day forward. Within some African societies, rites of passage were, until recently, literally inscribed on the body through a series of scarification procedures, performed on women either before they could get married or at the onset of puberty and after the birth of a child.14 Conversely, we learn from James Faris’ important study that ritual isolation was marked among the Nuba of Southeastern Sudan by a lack of desirable bodily adornment; non-participants who were isolated during initiation, funeral, or childbirth rituals would symbolically remove themselves by placing talc on their bodies to distinguish themselves from the participants whose bodies were oiled and shiny.15 In Africa today, many of the older practices have been abandoned in the context of missionary influence, colonial force, and the quest for modernization, and communication about life stages is largely achieved through a lexicon of clothing. Clothing is also the marker of life stages in India, to be discussed in detail below. Andrea Rugh’s book on dress in contemporary Egypt, and Liza Dalby’s study of the kimono both show how women designate their status in the life cycle by choices about colour, style and fit of dress.16

9 Space, like time, plays a major role in the choice and function of body art. As people move through the life stages, they are also literally moving in space, passing from one physical location to another in their daily lives. Many excellent studies have focused on the importance of geographical contextualization, furthering our understanding of how people conceive of their place in space. For example, Emma Tarlo, in her study of dress in rural Gujarat, India, discusses how women, moving through shared space, choose to shift into privacy while in public by covering themselves with a veil, making themselves temporarily inaccessible.17 The use of the veil — a portable means of creating private space — by women in the Middle East, Asia, and Africa is a fascinating topic, and one that has been studied by scholars, most notably by Fadwa El Guindi.18

10

Many studies of the purposeful display of ethnic body art concentrate on people who have been displaced from their homelands, either against their will — as in the case of Africans brought as slaves to America — or as refugees, such as the Hmong from Southeast Asia, or as willing immigrants, such as people from India settling in the diasporic communities of England, Canada, and the United States.19 An exploration of dress in the diaspora expands our understanding about the spatial dimension of native dress. Ethnic people living abroad often prefer to wear a "timeless" version of their cultural attire, since they lack the information, money, or resources that would enable them to keep up with the ever-shifting fashions back home. New, global styles — mixed and matched out of native and foreign elements to produce "fusion" designs — often return to the homeland, influencing the local elite to adopt fashionable new versions of their traditional dress that were invented in London, Paris, New York, or Toronto.20

10 One of the main functions fulfilled by dress is to mark the multiple identities of individuals, and therefore, to position them within their social networks. Because of the conspicuous nature of clothing and body art as a device of social communication, many works by anthropologists and folklorists have contributed to our understanding of society and how its structure and dynamic relate to bodily adornment, along with other collective forms of expression, such as mythology. Franz Boas, A. L. Krober, Claude Lévi-Strauss, James Faris, Andrew and Marilyn Strathern, and Alfred Gell, among others, have demonstrated the social importance of body art.21 Petr Bogatyrev’s landmark study of the costumes of Moravian Slovakia, published in 1937, beautifully shows how social messages — indexing wealth, age, marital status, social structure, outside influences, aesthetics, and magic — function simultaneously, layered one on top of another, in displays of dress and adornment.22

11 Body art defines individuals as members of a group; this is shown clearly by the example of the Kuna Indians, whose abstract cultural values are visibly rendered in the blouses that the women make.23 Items of adornment might express communal identity while simultaneously communicating urban or rural associations that are readily inscribed in the clothing styles men and women wear — as studies of Slovakia, Egypt, and Japan demonstrate.24 Dress also marks different factions within a society; a reading of the patterns, motifs, and colours of knitted Turkish socks reveal the communal, village identity of the maker and wearer.25 Finally, from Andrew and Marilyn Strathern’s classic study, and from Michael O’Hanlon’s subsequent field work in the Papua New Guinea Highlands, we learn that body paint, wigs, aprons, and other items of self-decoration, had (and still have) the power to unify a cluster of people as a coherent group, as allies, while differentiating groups of people, as competitors and enemies.26

12 Our understanding about the nature of body ornamentation owes much to museum professionals, whose careful research, meticulous conservation, and educational exhibitions provide a service to scholars and to the general public. Dress acts as an agent of social and ethnic positioning within different factions of society, while also creating a cohesive social unit in opposition to neighbouring groups — a point made repeatedly in the scholarly literature mentioned above — and this complexity can be visually expressed by displays of clothes in a museum setting. The Muzeul Ţăranului Român, in Bucharest, Romania, for example, has two distinct sections devoted to costumes: one in which the regional clothing of Romania is displayed, and another where the neighbouring cultures — Macedonian, Bulgarian, Hungarian, Turkish — are labelled and featured. In both sections, though lacking much written contextual information, the display is richly comprehensive in its presentation of clothing styles for both genders, as well as embroidery motifs, accessories, such as scarves, shoes, and jewellery, and even detailed depictions of hairstyles. Although people in Romania today wear the conventional modern clothes of the West on a daily basis, this permanent exhibition of what has now become special occasion dress is a reminder of a shared ethnic heritage.

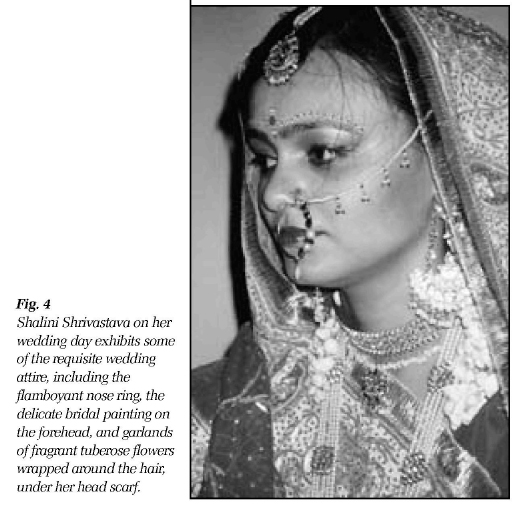

Dress and Adornment in Contemporary India

13 Working within the interdisciplinary tradition of the scholarship sketched above, I conducted field work in the holy city of Banaras, India, from 1996 to 2003, investigating dress and adornment among the Hindu population, interviewing men (jewellers, sari weavers, sellers of cloth and ornaments), and women, who use the products of men to construct their self-presentations on a daily basis. I found that women in India make conscious decisions about communicative potential when selecting items to purchase and when adorning themselves. Much is revealed about this purposeful assertion of the self as an individual and a member of society by looking at specific women, and the choices they make in the colour, fabric, cut, and print of clothes, in the material, workmanship, and design of jewellery, and most importantly, in the assemblage of this unit, worn to be seen in specific contexts of viewing and judgment. It is clear that women in India, like people elsewhere, manipulate their adornment as a means of expressing to themselves and to others the position they choose to adopt at every moment of their lives.

14 My ethnographic study was guided by the directions of inquiry developed in folklore, my field, which is interdisciplinary by nature, and most specifically, it was inspired by the material culture studies of the last forty years that have been conducted in the framework of performance theory.27 I found that different functions of adornment, though divided in the studies above, occurred concurrently. People asserted distinct temporal, spatial, and social identities at once. Aware of the variables of communication, they deliberately man aged their body presentations to fit personal agendas.

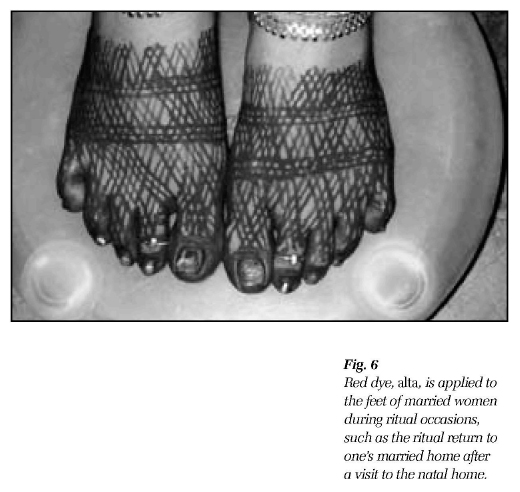

15 Although in the discussion to follow, for the sake of this paper, I break the broad concept of positioning into two categories — temporal and spatial — they actually function together as a means of communicating social position. Variables in choice of adornment, while constantly changing due to individual, seasonal, and geographic factors, act, nonetheless, in accordance with shared social perceptions of appropriate presentation, conditioned by religion, region, caste, and family restrictions. As people position themselves in time and space, they are, at the same time, grounding themselves securely in their society.

Temporal Positioning

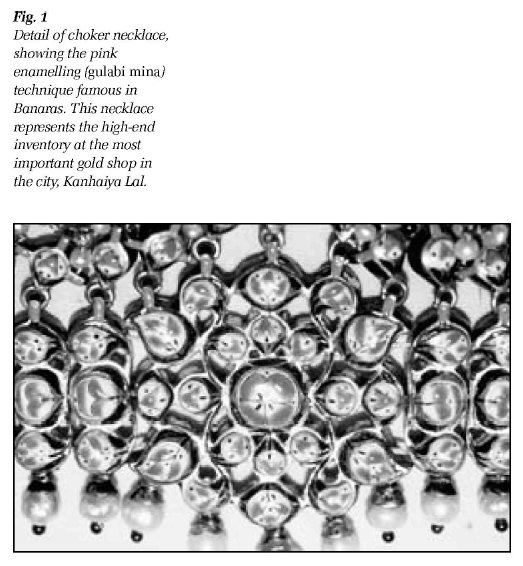

16 Men and women in India position themselves at once in different temporal realms, some broad and historical, others intimate and personal. I chose not to follow the grand, conventional approaches of history, but rather to concentrate on more modest readings of history, on time as it pertains directly to people’s understandings of themselves. I did not begin in libraries, archives, and museums. I spent my time in the shops, ateliers, and homes of Banaras. By observing the designs of the jewellery made in the city’s hundreds of small gold and silver workshops, and the motifs of the thousands of gold brocaded saris produced, I discovered a deep interest in maintaining a particular — Muslim — aesthetic that is associated with the past splendours of the Mughal Empire. By creating Banaras’s famous pink enamel decoration on the back of kundan-style golden ornaments, encrusted with gems, Hindu goldsmiths purposely position themselves in line with the city’s renowned jewellery-crafting tradition that runs back to Mughal times. Their customers, by buying and wearing these jewels, likewise position themselves in a historical continuum of aesthetics and taste, since most items of jewellery in the city are made only on commission by private individuals or by the proprietors of shops that sell gold.

Display large image of Figure 1

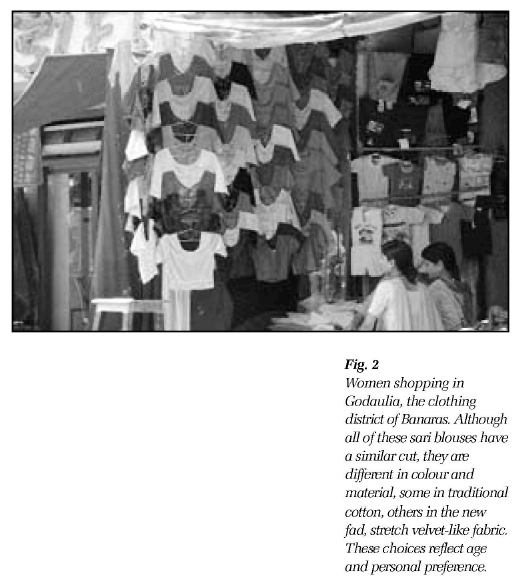

Display large image of Figure 117 Banaras is known throughout India for its silk, brocaded saris — called Banarasi saris — that are worn by brides throughout the country and widely in the diaspora. The Muslim weavers and sari merchants, like the goldsmiths and owners of jewellery shops, are aware of the beauty (and demand) for historical designs and motifs, and they are consciously involved in the revival of a glorious style from the past. Producers and merchants simultaneously cater to current demands while attempting to influence their customers’ taste, so they must be well versed in historical styles, current fashion, and the ubiquitous "timeless" classic. Both merchants and female customers must also be concerned with the fashion history of the last few years, lest their choices seem hopelessly dated. Some old designs are a part of a vibrant revival, others are merely out of fashion. Merchant and consumer must know which is which, to prevent the embarrassment of unsaleable stock in the godown (warehouse) or unwearable clothes in the armari (wardrobe).

18 Some women choose to position themselves, not in the historic past with revived or classic designs, but rather in the contemporary moment by following what Indians call, in English, "the latest fashion." Fashion, by definition, is ephemeral, and therefore, one must keep up with it constantly. In India, the actors and actresses of the Bombay28 movie industry — known as Bollywood — serve as the role models for fashion. Their outfits, on camera and off, are reported in the fashion and "filmy" magazines that are carefully scrutinized by many. I have documented some of the Bollywood-inspired fashions seen in the movies, then sold in the shops, and finally worn by people in the streets. These trends have included preferences for clothing in a particular shade of green; a style of backless sari blouse; flared salwar pants worn with a short kurta top; and a type of bangle with dangling rhinestone ornaments attached.29 Following fashion is a choice, one that not all people decide to make. Based on my interviews with women, I surmised that four choices are open: to be slightly ahead of the fashion, being a style setter; to be with the fashion by wearing the new style when everybody else is; to be behind the fashion by continuing to follow an outdated trend; and finally, the last option chosen by some of the women with whom I spoke, is to ignore the fashion altogether, opting instead to wear classic "timeless" pieces. In this way, women may position themselves slightly in the future, firmly in the present, faintly in the past, or they may suspend themselves beyond time’s flow.

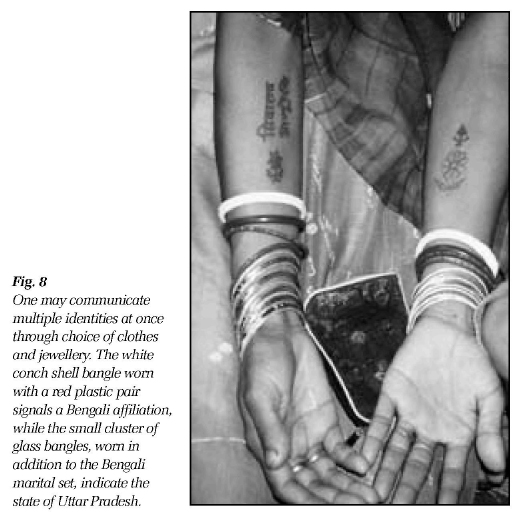

19 The most important function fulfilled by dress in India — beside the practical ones of clothing the body and identifying members of different genders, regions, and religions — is to mark a stage in the life cycle. This is particularly important for women. There are generally acceptable rules in different religious and regional and caste communities that mandate who wears what and when. Among Hindus from Banaras, in the state of Uttar Pradesh, women (and to a lesser extent men) mark all of life’s transitions with an absence or presence of specific body decorations that serve as instant, visual communications of sexual status, positioning the individual into society’s different categories (and, therefore, into acceptable public behaviours.)

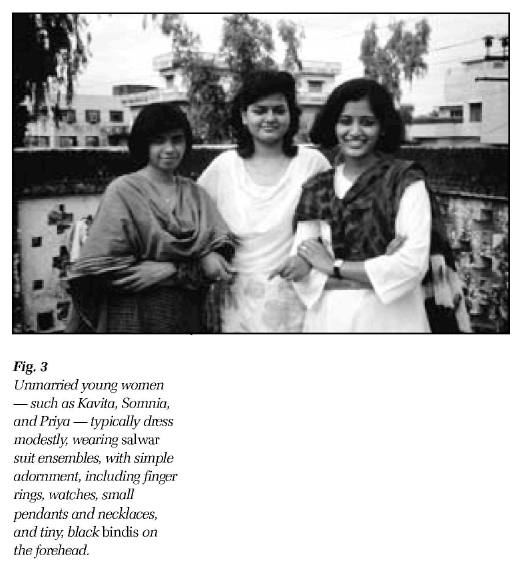

20 The beauty of babies is not flaunted, out of a real fear of attachment, devastating should the infant not survive, or of the evil eye cast by jealous neighbours or malignant spirits. Little girls, if the parents can afford it, wear frilly dresses, tiny anklets, bangles, earrings, and perhaps even nose rings. Girls may innocently partake in wifely adornment at ritual occasions, wearing henna on their hands and alta red dye on their feet. At about the age of twelve, at the onset of puberty, it becomes inappropriate for girls to reveal their legs, and they usually start wearing jeans and salwar suits (three piece ensembles consisting of a salwar, baggy drawstring pants, a kurta tunic top, and a matching long scarf, called a dupatta or a chunni). In addition to abiding by the restrictions on not revealing too much of the developing body, adolescent girls, until their marriage, wear the minimum amount of tiny, "sober" jewellery, such as small earrings, a single finger ring, and no makeup. Women attending the university often wear a small, black bindi on their foreheads, carefully avoiding shades of red and maroon, as these indicate married status.

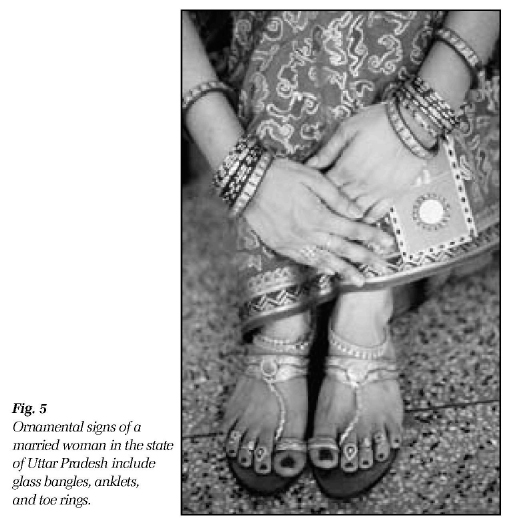

21 Marriage celebrates the beginning of a woman’s life as a decorated being. On her wedding day, a bride will wear the most jewellery she will ever have on, the ornaments functioning to commemorate the occasion, and to showcase her parents’ wealth30 and her personal beauty. Golden ornaments are worn on the bride’s forehead, ears, nose, neck, wrists, hands, and fingers; silver jewellery adorns the ankles and toes. Immediately after marriage, young wives must wear the "compulsory" wifely ornaments for the rest of their lives, so long as their husbands are alive. (While they are still technically married, a widow is believed to have left the auspicious marriage stage.) The mandatory items for married women include sindur (red powdered colour on the hair part), a bindi on the forehead, glass bangles, toe rings, and a golden neck lace.31 A newly married woman further visually displays her particular position by wearing more jewellery than others, especially during the first years of marriage when wives are encouraged to wear "gaudy," brightly coloured saris, many bangles and noisy bell anklets. Both men and women have told me that this is done in the hopes of visually exciting husbands, and starting the process of producing children.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2 Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3 Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4 Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 522 Clothes and ornaments further convey a woman’s stage in the life cycle by communicating the gradations found within marriage. When a wife has been married for a few years, and is ready to assume more domestic responsibility in the joint-family household, she wears less fancy saris, and less jewellery, as these can be ruined during household chores. Mothers of young children may further eliminate certain items of jewellery while caring for their infants, such as rings that may scratch the skin or glass bangles that may break and injure a baby. Someone conversant with the variables of bodily adornment can instantly tell if a woman is married, approximately how long she has been married, and even if she is a young mother, a fact revealed by the marked absence of certain ornaments, such as bangles or kara golden bracelets, for this mandatory wifely jewellery is put aside in the interest of the safety of a baby.

23 As life progresses, the kinds and amounts of adornment changes. It is considered socially unacceptable for an older woman to be fully ornamented and clad in bright colours "like a new bride." Women, particularly those with older and married children, start wearing "sober colours" in pastel shades with small, subtle prints. Many women, while continuing to wear the obligatory glass bangles, scale down from a half dozen to one or two per wrist. If a woman becomes a widow, she reverts back to an unmarried state in the marked absence of jewellery. She must remove and never again wear the marital signs: glass bangles, sindur, bindi, and toe rings. Widows also communicate their unfortunate (and inauspicious) state by an absence of colour for the rest of their lives, having to wear a white sari until their deaths.32

24 In addition to the short, immediate history of fashion as garnered from magazines and Bollywood films, women are interested in their own personal histories, defined not only by the rites of passage mentioned above, but also by changes to the self that are marked without ceremony, such as losing or gaining weight, cutting one’s hair, or even developing a sudden fatigue with a certain colour, style, or design. Mukta Tripathi, a housewife from Banaras, has, since turning forty, started wearing saris in muted tones and smaller prints, as she believes these flatter her age and thickened figure, helping her achieve her goal of a "dignified look." Other modes of marking personal time through clothes and ornaments include visually conveying participation in religious rites and social rituals. Women, for instance, apply alta red dye to the outer periphery of the soles of the feet when returning from a visit to the natal home.

25 Many women in Banaras mark the changes of the seasons by their choice of saris and ornaments. Besides the obvious selection of fabrics deemed suitable for certain weather — cotton in the summer, synthetic blends such as georgette in spring and autumn, and silk and wool in the winter — the choice of colours also reflects a reaction to the weather: light pastels in the summer, and deep, dark colours in the winter. The colour green, in bangles or clothing, is often chosen to celebrate the beginning of the rainy season with the arrival of the month of shravan in late July or early August. During this time, henna is also applied to the hands; although henna leaves a maroon dye on the skin, it is a green plant, and therefore, associated with the onset of the rainy season.

26 There are seasonal changes, and weekly changes as well. Many religious women engage in a cycle of weekly worship by keeping a fast on a certain day of the week that is associated with one of the Hindu gods. Kamala Pandey wears a yellow sari on Thursdays, on the day associated with the god Vishnu, to whom she prays and for whom she keeps a regular fast. Specific times of the day can also be reflected in the clothes people wear. Early in the morning, women might signal that the household chores have not been done by continuing to wear yesterday’s dress in which they slept. Only once the chores have been completed will they bathe and put on a new sari. When their husbands arrive home from work in the late afternoon, many women, in anticipation of their return, wash up, re-plait their hair, re-apply eyeliner or lipstick, indicating visually the end of the work day and the anticipated spousal reunion that many couples look forward to.

27 In the scholarly literature on body art, temporal variables play a major role in the categorization of modes of body modification as temporary (such as makeup or hairstyle), or as permanent (such as tattoos or piercing). My extensive interviews with people in India helped me refine this temporal distinction by seeing the importance of permanent and temporary adornment, not only as it applies to the duration of the specific ornament (as measured by the technique and nature of application), but also as it pertains to the amount of time one intends to own and wear the item. When buying costly pieces, such as gold jewellery or silk saris, women spent more time shopping and often brought companions along to help them carefully choose items that would become lasting objects in their personal repertoires. When buying cheap, "artificial jewellery" on the other hand, women were more inclined to follow a Bollywood fad and to give up that piece as soon as the fashion was over. A final way in which women position themselves temporally through their deliberate choice of clothing and adornment has to do with the contrast of permanent versus temporary as measured by the amount of time, in hours, that they plan to wear the item in question. Uncomfortable, cumbersome clothes, shoes, and jewellery can be tolerated if one knows that the item need not be worn for long. By looking at a woman’s dress, and judging by her motion, one can guess if she intends to stay at the wedding reception through the night (when the marriage ceremony takes place) or leave just after dinner.

Display large image of Figure 6

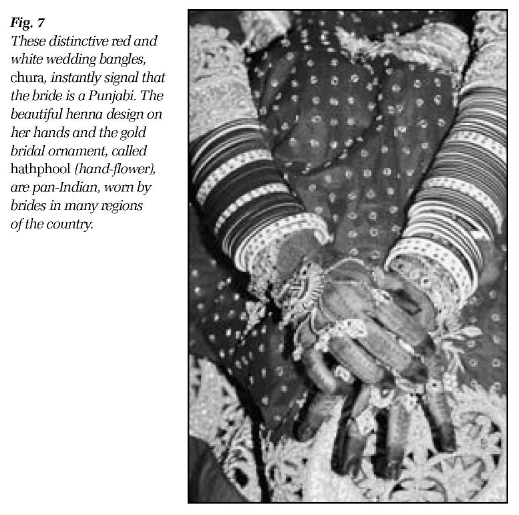

Display large image of Figure 6 Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 7 Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 828 We see that a major function of dress in Banaras is to position the self in layered temporal settings that occur simultaneously. Women reconcile the broader culturally shared historical and contemporary styles with their own life stages. These stages can be grouped into three broad categories: pre-marriage, marriage, and post-marriage. The gradations within these, particularly the many sub-stages of the marriage phase, are also visually marked. And finally, the body aging and changing in personal time, the passage of the hours of the day, the days of the week, the months and seasons — all are reflected in women’s clothes and jewellery. If one chooses to, and many do, one can position herself not only in her general life stage, but precisely into a time of day by what she is wearing now, as opposed to what she wore two hours ago and what she will have on three hours from now. These messages are there to be read, whether or not a recipient is available to decode the meaning. Personal communication to the self can fulfill the function in a circle of self-reflection.

Spatial Positioning

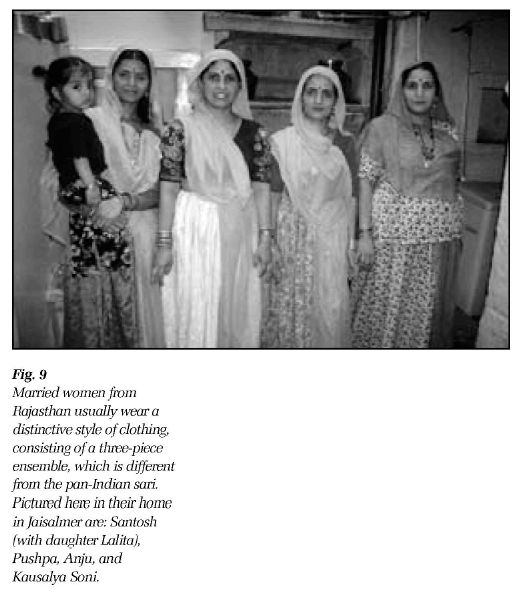

29 Besides positioning the self in historical and personal time, adornment is a way of anchoring oneself in physical space. Indian men and especially women, regardless of where in India they are, may instantly communicate their region of origin by their clothes and ornaments. Although the sari is an unstitched cloth, the way in which it is draped, tucked and wrapped is regionally specific33 and readily identifiable. Similar geographic associations are expressed by men’s clothes, turbans, and even mustaches. Within the broad frames of regional dress, there are variations associated with specific cities and villages. An outsider, a tourist, will see a group of women as Indian — judged by the national, pan-Indian symbols of sari and bindi — but somebody from within the country will most likely be able to decipher the coded message of state and region. If the woman’s nose ring is on the right, the woman is from one of the states of South India; a left piercing indicates one of the northern states. Other variables, such as the gold and black manglasutra marriage necklace, a cluster of ivory bangles, or white flowers on the hair, all indicate the general part of the country from which a woman comes.34 More subtle features of adornment, such as the style of embroidery or the colours and details of mirror work motifs, send clear messages of specific village affiliation in the states of Gujarat and Rajasthan.35 And a religious communication is implied throughout this discussion, since all of these signs are specific to Hindus.

30 Permanent or temporary geographic displacement can also be detectable, if the wearer so chooses. Tara Mukherjee, a woman from Calcutta who lives in Banaras, wears her Bengali marriage bangles — a white conch shell bracelet worn with a red plastic one — layered behind the Banarasi glass bangles. In this way, Tara communicates her marital status as defined in both states, and she also expresses her regional affiliation, being a Bengali who now lives in Uttar Pradesh. This example showcases migration, but temporary displacement may also be self-consciously displayed. In the markets of Banaras, one can easily detect women from the neighbouring villages who come to the big city to shop. They proudly exhibit the aesthetics of their village style with hoop nose rings, and orange, not red sindur powder on their hair parts, and with shiny, "gaudy" saris, purposefully mismatched with the blouse, which contrasts in material, colour, and sometimes design with the sari. City women find this look distasteful, but village women prefer a bright, energetic ensemble. By not muting their visual presentation, these women are symbolically positioning themselves in the village while they are physically present in Banaras.36

31 In order to understand how people negotiate the different spatial realms of their lives, let us look at one individual, Neelam Chaturvedi, a Punjabi school teacher who has married into a family from Banaras. Neelam, like most people, does not divide space into the simple categories of public and private, but rather defines space by the people who occupy each arena, and the potential relation ship she might have with them. By noting her choice of dress in each of these realms, Neelam’s personal comfort level and social intentions are revealed. Neelam and her husband, Vidhu, live in a joint-family house hold with Vidhu’s brother, sister-in-law, and his widowed mother. Neelam’s self-presentation is shaped for different contexts, both outside of the house and within the compound, since the audience level varies in each area of the home.

32 The most intimate space is their upstairs bedroom, where the couple retreat for the night. Here Neelam dresses to please Vidhu, whom she truly loves. While in the bedroom, Neelam wears dozens of Punjabi wedding bangles — items considered socially inappropriate for a woman who is not a newly married bride — for the private pleasure of her husband, who loves to see jewellery on her. Neelam does not like to wear so many bangles, so when her husband is away on a business trip, and her bedroom becomes a totally private space, where she must dress to please only the audience of the self, she removes the mandatory wifely ornaments she must wear at all times, lest she be reprimanded by her mother-in-law or some other relative.

33 Moving downstairs to the shared familial areas of the living room, kitchen, and formal drawing room, Neelam must dress in accordance with the wishes of her mother-in-law, the matriarch of the household. Here the audience includes members of both genders, house servants, and even unexpected guests who might arrive unannounced. In her own home, Neelam must appear well kept, yet modest, adhering to the social rules for appropriate dress. Being overdressed in fancy clothes, with makeup and jewellery, in one’s own home is considered as inappropriate as being too underdressed in clothes that are raggedy or revealing. Once downstairs, Neelam must make sure to wear the compulsory wifely ornaments — glass bangles, sindur, bindi — as her mother-in-law would disapprove and reprimand her, worried about what others might say if they saw how brazen the daughters-in-law of this family were. At home, Neelam regularly wears a salwar kurta set, commonly referred to as punjabi, as this clothing style is more comfortable for Neelam, a Punjabi herself.

Display large image of Figure 9

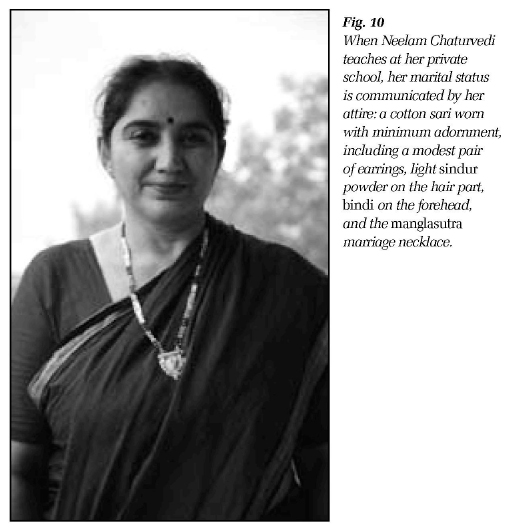

Display large image of Figure 934 Neelam works outside of the home, causing her regularly to move through other physical arenas in which she is seen and judged. The school where she teaches offers a different category of audience members: fellow teachers of both genders and young children. These people represent a stable core of non-familial people; neither strangers nor intimates. For the sake of her students, and in compliance with the official dress code of the private school, Neelam, while teaching, wears a sari — the appropriate outfit for a married woman in Banaras — and prominently displays the marital ornaments, though she wears an understated version of these requisite items. In other words, to appear "dignified," she must comply with the socially acceptable attire for a married middle-aged woman. If she were to wear a silk sari, lots of bangles and big dangly earrings, she would be inappropriately dressed for work, and she would distract the distractible students with her extravagant, party look. Women who work outside of the home must negotiate this arena carefully, looking attractive and professional without being too flashy.

35 While attending parties and wedding receptions, Neelam dresses to meet the expectations of her peers, people of her social and financial standing. Here Neelam says she wears the kinds of gold jewellery and fancy saris that others also wear, since she represents her family’s social standing by her choice of dress. The judgments people make on social occasions are based on readings of the appropriate attire for Neelam’s social standing, her age and the sub-stage of her marital status, returning us once again to the factors of personal history and the temporal frames of reference discussed above.

36 Arenas more public than the party or workplace include the market and other parts of the city, where although the audience is comprised mostly of strangers, one might run into an acquaintance, and therefore, one must be careful to look and behave appropriately. These commercial areas, occupied by what many in India refer to as the "local public," prevent one from enjoying anonymity in a public context.

37 While on holiday, Neelam, like many women in India, experiences the most public of all contexts, since no one is this locale will pass judgment and gossip back to her mother-in-law about her dress. During vacation with her husband, Neelam wears blue jeans and trendy "black metal jewellery," things associated with younger, unmarried Indian women or foreign tourists. Far from home, Neelam expresses a freedom achieved by geographic distance. Women dress a certain way in their hometown, seeking visual approval. When travelling, many women present themselves as they please, not caring about the visual reactions on the streets, sometimes intentionally subverting the social restrictions imposed on them by local communal standards. Although Neelam has not travelled to England or the United States, Indians in the diaspora experience yet another layer of geographic displacement, extending the spectrum further, and adding to the complications of personal choices.

38 The relationship between adornment and the context of seeing, and how communication is manipulated, will become still clearer when we take a brief look at the works of Indian authors who write about the diaspora. In the case of an Indian women temporarily visiting abroad, we see in Anita Nair’s novel Ladies Coupé,37 that a character is able to persuade her husband to let her wear Western clothes while visiting New York because no one will know her there. For Indian women who are living abroad, native clothes and jewellery function as a sign of ethnicity, and so form a means by which to meet other displaced Indians. This is illustrated in a recent short story by Jhumpa Lahiri38 in which a lonely Bengali man in Boston follows a mother and her child after having spotted the characteristic red and white Bengali wedding bangles on the mother’s wrists. For first- and second-generation Indian women, born abroad, Indian clothes and ornaments express not a temporary displacement due to a vacation or immigration, but rather a desire for connection, resulting often in a communication of pan-Indian identity, not necessarily of region or ethnicity, as shown by Amita Handa in her sociological study of Indian young women in Canada.39

Display large image of Figure 10

Display large image of Figure 1039 We see that body art, unlike other forms of material culture, such as architecture, furniture, or pottery, is used as an ambulatory means of positioning the self in every occupied space, asserting nuanced notions of public, shared, and private spaces through the choice of clothing, adapting to the present geographic situation without losing attachment to one’s own place.

Conclusion

40 By adjusting one’s bodily adornment in response to shifts in temporal factors, however culturally defined, and to the varied contextual arenas in which one operates, one is able to communicate maturity and accomplishment, individuality and conformity, and familiarity and distance, while positioning the self at once artfully and meaningfully in space and time. By taking a multi-faceted scholarly approach to this task, looking at different variables that affect one’s presentation of the self, we aim for a comprehensive understanding of the self-conscious messages human beings send about themselves and their societies, when they take control of the most intimate and meaningful medium they possess for communication: their bodies.