Articles

Making and Metaphor:

Hooked Rug Development in Newfoundland, 1973-2003

Abstract

The hooked rug has risen to iconic status as a representation of Newfoundland and Labrador crafts. The rug has evolved from being a mostly functional item, used to keep people's feet warm, to a production-line commodity and, recently, has come to prominence as expressive culture. There are parallels in the American Craft Movement wherein commodification often changed, or even usurped, meaning: the creative act was supplanted by the emphasis on the product itself. Value becomes a socio-economic/socio-cultural determinant.

Résumé

Le tapis au crochet a maintenant caractère d'em-blème'de l'artisanat de Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador. Autrefois article principalement fonctionnel, qui gardait les pieds au chaud, il est devenu un produit de travail à la chaîne, puis, plus récemment, un élément d'expression de la culture. Il y a des parallèles à établir entre cette évolution et celle de l'American Craft Movement, au cours de laquelle la réification a souvent changé ou même usurpé la signification de l'artisanat : l'acte de création a été supplanté par l'accent mis sur le produit lui-même. La valeur devient un déterminant socioéconomi-que et socioculturel.

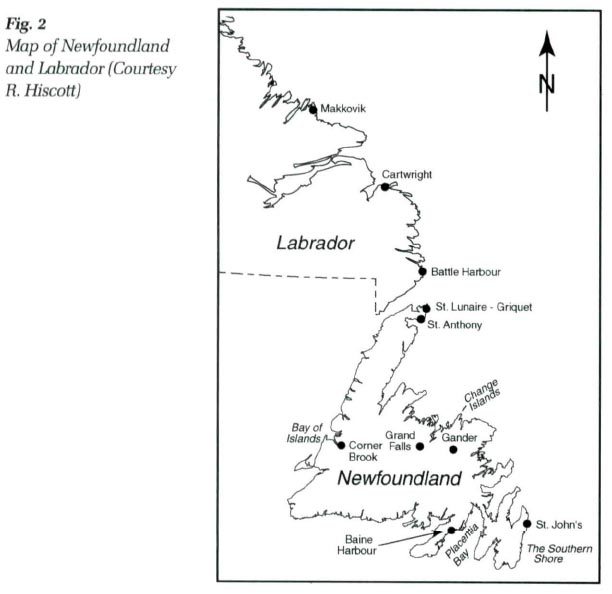

1 During her 2003 summer holiday in Newfoundland, Lynda Yolland made a point of visiting several St John's craft stores and antique shops, seeking out hooked rugs, or hooked mats, as they are called in Newfoundland and Labrador. She had been looking for a hooked rug for several years; her search in Montreal was usually carried out at an oriental carpet emporium, Ararat, which sold new and old carpets, some of which came from estate sales. At one time, Lynda had seen a beautiful hooked rug, selling for $100. However, she and her husband had just spent nearly $3 000 on carpets for their house and a further expense seemed superfluous. But she loved the rug and a week later phoned Ararat; alas, the rug had been sold. So, when Lynda and her friend, Judy Bastedo, who lives in St John's, were browsing at a collectibles store (The Old Curiosity Shop, located on Bond Street), and found a "filthy but unstained hooked rug, which was in good repair, no tears and not much worn" selling for $100, Lynda bought it.1

2 It measures approximately 50 cm X 90 cm; it has green flowers in two opposing corners and differently shaded green fleurs-de-lys in the other corners. The central flower is green with a much lighter interior. The interior colours of the mat are shades of grey, beige and a "tweedy" colour; there is a 5-cm scalloped border around the edges, in dark greys and blues (Fig. 1). She took it home to Montreal and had it cleaned by Ararat Carpets, at their specialized facility. Lynda says that the mat, which is in her bedroom, is somewhat faded compared to its back side but is in good repair, and she is very happy with it. It means a lot to her because she had been looking for a mat "for a long time" and now has one that is her "first one" and might not be her last. It carries several further meanings: when she was a child, Lynda's family spent late spring until the end of summer in a hunting lodge in the Laurentians, while her father worked in the Eastern Townships. There were many hooked mats, "usually of scenes like foxes," that were on the walls. Lynda assumes that this was in place of "expensive art." There were also floor mats with geometric designs scattered around the lodge. She associates these times with happy events. The mat she bought also reminds her of her vacation with Judy during a warm, Newfoundland summer. Her family and Judy's spent lots of fun times together, eating, drinking and touring with the children. The hooked mat makes Lynda "very happy"; she likes it not just because she thinks she got a good deal, but because the mat pleases her. Lynda has now started a mat hooking course and looks forward to making her own mat someday.2

Display large image of Figure 1

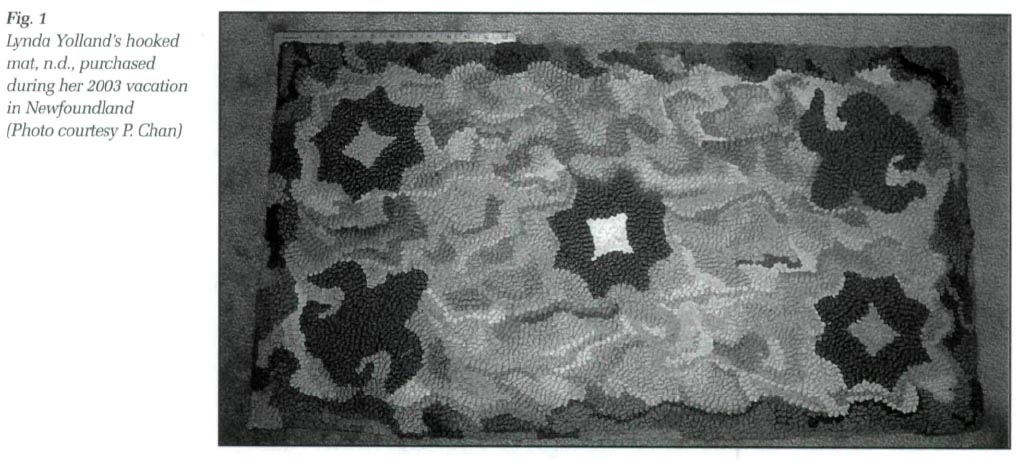

Display large image of Figure 13 What does this anecdote mean? What significance does the object (a hooked mat) have for Lynda? Such objects are artifacts in that they are made by hand and they express the patterns which exist in the minds of their creators, and of the culture at large: Henry Glassie notes that "the study of material culture uses objects to approach human thought and action."3 My purpose in this paper is to trace the path of the hooked mat (as a representation of Newfoundland crafts), from the time when it was mostly a functional item, used to keep people's feet warm, to the present time, in which it still warms people's feet but can be seen at craft fairs and shops, in art gallery exhibits and over the mantelpieces of the "celebrated," ranging from those in the arts to politicians — in short — the intelligentsia. The key phrase here is not "hooked mat" but "the path," for I am attempting to trace its journey in the lives lived by those who made it. produced it, assembled it, marketed it and consumed it. The feeling of déjà vu cannot help but arise, for the marketing of hooked mats was practised along the Labrador coast during much of the last century by Dr Wilfred Grenfell and his associates.4 For my purposes I am concentrating on developments in the making and production of mats here in Newfoundland and Labrador in the past thirty years (Fig. 2).

4 In 1972, Glassie astutely observed that "if a pleasure-giving function predominates, the artifact is called art; if a practical function predominates, it is called craft."5 By 1991, the debate still existed: Jules David Prown, noting "the word 'art' is embedded in the word 'artifacts'," was "troubled by the relationship between what is considered art and what is not."6 Unlike his 1982 stance, in which he divided material culture into six categories ranging from the most aesthetic to the most utilitarian, Frown allows that while "art is quite clearly material that is expressive of belief," that belief is more intentional than the often unconscious expression of belief embedded in artifacts. I would say that the word craft could be substituted here in place of artifact.7 Craft is the often unconscious expression of belief. Who is to say, then, whether Lynda's hooked mat is art or craft? I endeavour to show that it is both; for I do not see much distinction between what is made to be used and what is made to be collected/admired. I shall address questions such as "When does craft become art?" and, "When does art become craft?"8

5 When does a hooked mat stop being functional only, and take its place on the walls of galleries as art? When does it cross the line between instrumental versus expressive artifact? As Glassie observed in 1972, "there is no artifact totally lacking in art," and I suggest that even the greatest objet d'art could be employed as a foot-warmer.9 The chief attribute of craft may be its practical function but even craft represents a worldview of an era. Belief patterns can be read from artifacts as words can be read by linguists; a system of repetition leads to a text, which can be read in a variety of ways. There are similarities between language and material culture; just as scholars like Chomsky and Hymes see signs in language, Glassie sees an artifact as a text but, unlike a story, which refers to a temporal experience in one direction, the artifact belongs to the spatial experience, which goes in all directions at once, so that there are many meanings.

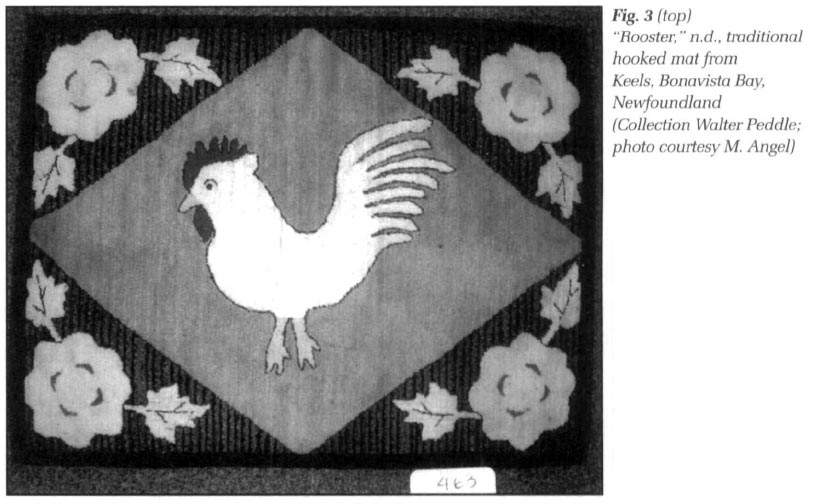

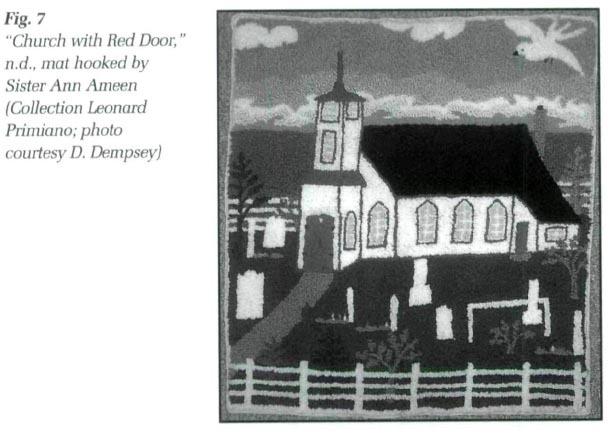

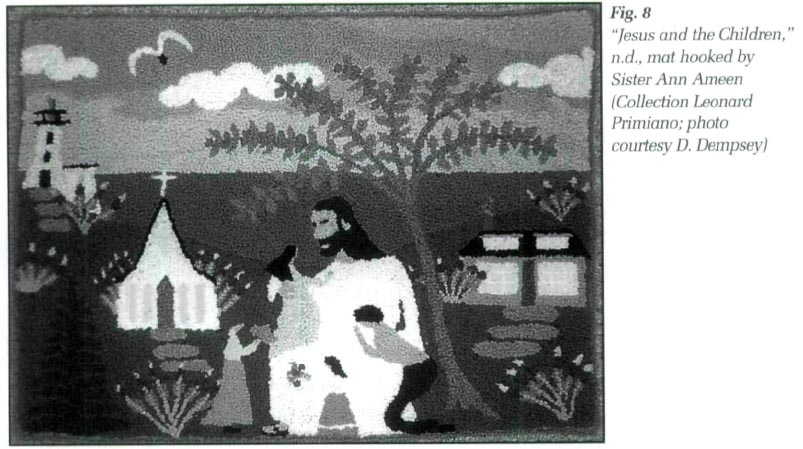

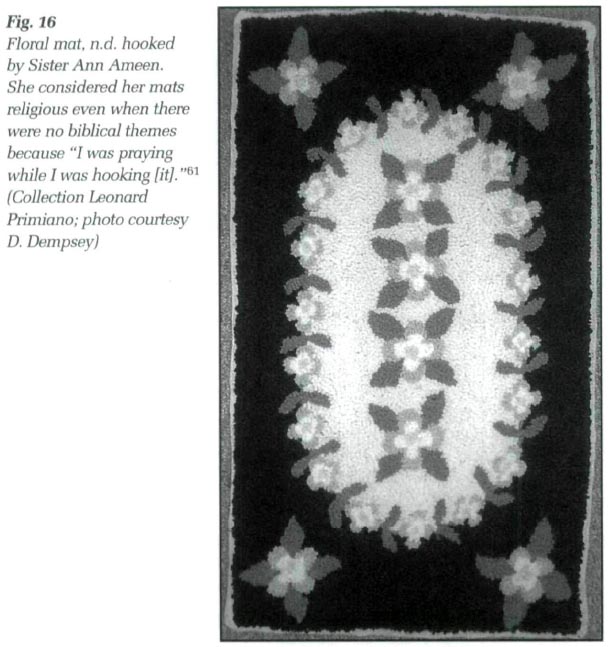

6 Hooked mats have characteristics that are defined by a pattern; this pattern allows the mats to be "read" as a text, with limits. Meaning, however, has no limits and will depend on the contexts in which the mats are produced. As in the manner described by Glassie. mats are artifacts that fit into contexts of creation, communication and consumption.10 Typically, mat makers in Newfoundland and Labrador are female, so I will refer to "women," although there are some male mat bookers (St John's retiree, Bruce Simms, who was born near St Anthony, took up the hobby in 2002). Traditionally, women have hooked mats in their own homes, by watching and learning; this takes time and concentration to develop the skills that replication demands. The context of memory can be played out, as in the replication of one's pet cat or one's community (Fig. 3). The context of communication is a large part of the performance of rug-hooking. One can either communicate literally (as in the case of Newfoundland mat maker Sister Ann Ameen, who worked inspirational and biblical quotations in her mats as representations of her faith (Fig. 4)), or one can communicate metaphorically through demonstration of one's artistic skills, one's taste or even one's ability to keep feet warm.11 Ideally, creation and communication coincide. The mat can be donated by gift, legacy or through commerce. At this point, the mat goes from its creator to its consumer. "Consumption, like creation, collects contexts in which the meanings of the artifact consolidate and expand."12 It is at this point, also, that the hooked mat can go from being merely the foot warmer next to the bed, to the heirloom from one's Aunt Mae, to the mat sold at Pollyanna Antiques in the provincial capital of St John's, to being someone's latest art acquisition.

7 In 1972, Memorial University of Newfoundland (MUN) Extension Services ran several arts and craft courses around the province. These were usually aligned to educational facilities and featured short courses in painting, drawing or pottery. The teachers were artists such as Gerald Squires and the late Don Wright. Several people made items but there was no formal structure for craftspersons; there were no organized events or collectives at which one could sell work. Apart from Joan Short's shop, St Mary's Bay Crafts, on Cochrane Street, in St John's, there was very little opportunity for crafts/ craft supplies to be bought or sold. During that year, MUN Extension Services held two meetings (in June in Gander and in November at Queen's College on the MUN campus in St John's), to try and bring some formal structure for craftspersons to meet and sell their work. People interested in crafts, art teachers in schools, crafts teachers, economic development workers and vocational teachers were contacted and a committee was formed to write a draft constitution. In November, a board was elected and by September of 1973, the Newfoundland and Labrador Crafts Development Association (NLCDA) was incorporated.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3 Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 48 The following year, Anna Templeton, who was a supervisor with the Craft Training Division of the Department of Education, discussed the concept of craft fairs with Donna Clouston, Albert Rippenger, Isabella St John, and Peter Thomas, an artist employed by MUN Extension Services. They decided that they would initiate St John's first craft fair. The group contacted "everybody who'd ever taken an art or craft course from MUN Extension" announcing that they would hold a craft fair, on the upper concourse of the Arts and Culture Centre in November of 1973; anyone with crafts to sell was invited to "show up."13 On a day coinciding with the Santa Claus Parade, which was held nearby, thirty to forty craftspersons arrived, filling tables borrowed from a church basement. Once the parade ended, the chilled participants turned up, in droves! The first craft fair, organized independently, was a huge success. By 1975, the NLCDA had a regular newsletter and soon organized its own fall craft fair. Within a year, the NLCDA added a summer craft fair and had a fall craft fair in Corner Brook, on Newfoundland's west coast. Craftspersons could now meet each other and discuss production and meet those consumers who bought their work. For those consumers, this venue was the only opportunity to buy crafts from and talk to those who made the product. Within a couple of years, crafts would be sold to middle-class locals and tourists at St John's shops such as Newfoundland Weavery and The Cod-Jigger, but there one could not discuss the product with its creator; the stores also charged higher prices.

9 MUN Extension Services, meanwhile, was spawning a group of artists, several of whom had come from outside Newfoundland, who would be intertwined with crafts persons across the island and in Labrador. Many of these would be associated with both St Mary's Bay Crafts and Studio as well as the artist-run studio in St Michael's on the Avalon Peninsula's Southern Shore. Artists had been hired by post-secondary institutions since the late 1960s; now artists and craftspersons were aligned with government workers in the Department of Rural Development The province of Newfoundland and Labrador has a population of approximately 500 000. In the larger centres, it is not difficult to know a certain number of people who move in the same circles; as a friend of mine used to say, "St John's [which has a population of 130 000] has a hundred people."14 Those who worked for the Department of Rural Development were often friends with those who made crafts and those working within the university environment. People worked together. It was not surprising that, as the cultural "revival" of the seventies developed, so did an interest in crafts.15

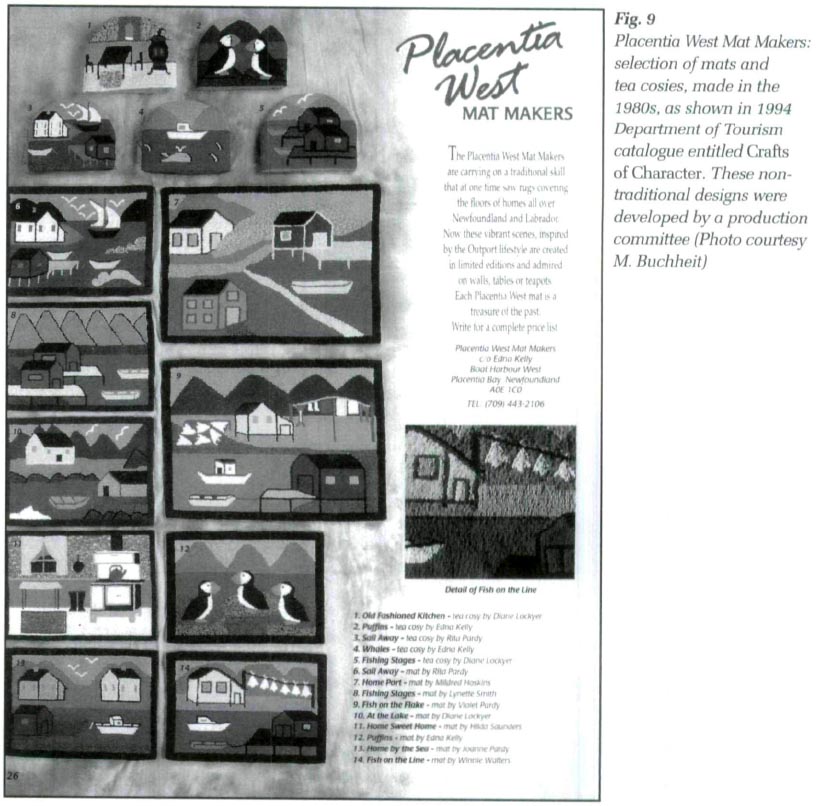

10 In 1979, a publication edited by Frances Ennis featured Newfoundlanders who practised traditional skills, one of whom was Louise Belbin, a hooked mat maker.16 Mrs Belbin's mats were also reproduced and/or discussed in scholarly publications.17 The profile of the mat-maker as traditional craftsperson was beginning to be raised. Around 1979-1980, Lois Saunders, who had completed a course in community development in Ottawa in 1977, was working as a rural development officer. She helped women to organize a craft business: they formed the Placentia West Mat Makers Association. The incentive was to enable the women, who already had good technical skills in making traditional mats "with flowers and geometric designs" at home, to develop a business enterprise whereby their rug-hooking skills could earn them wages.18 So the women — and it was a gendered enterprise — came together to practise a craft that some of them had known from their youth. These women were in the same position that craftspersons had been in in 1973: they had traditional skills but they needed more training, to ensure quality control. Craftspersons needed materials and supplies and they needed to know where to sell. Over the next five or six years, these needs were met through the NLCDA, and the community of craftspersons grew.

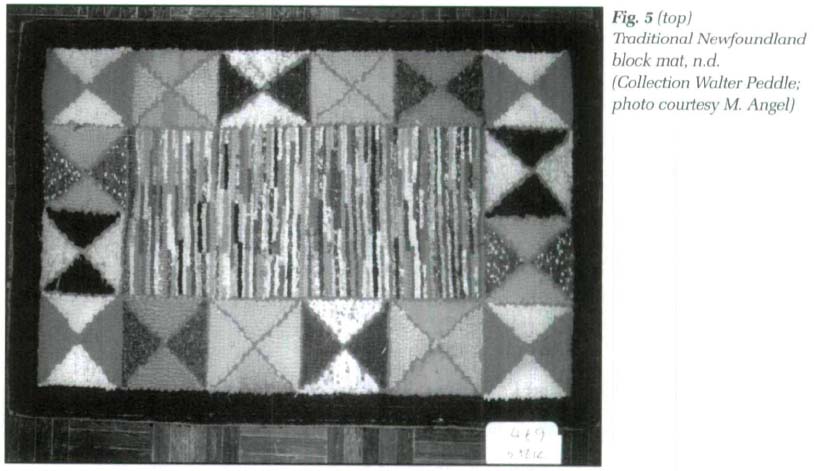

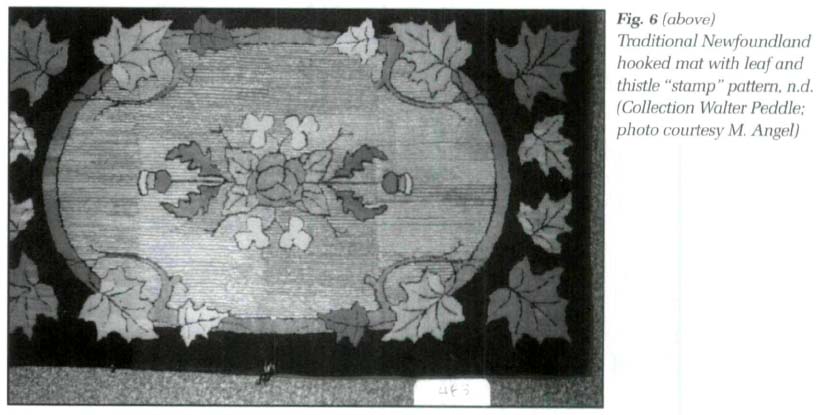

11 In 1979-80, Saunders contacted Colleen Lynch, who lived in St John's and who had an art and design background. Lynch had been aware of the unique qualities of Newfoundland hooked mats and had researched them since 1977; she eventually co-ordinated an exhibition of hooked and poked mats in 1980. Lynch came to Baine Harbour, Placentia Bay, to give workshops in rug hooking. More importantly, Lynch helped the group develop a line of hooked mats to sell to the public. Unlike the usual block (Fig. 5) and floral designs (Fig. 6), the designs on these mats were to be "what the women saw outside their kitchen windows," such as boats, cod hanging on a clothesline, or indoor scenes such as boots next to the stove.19 Rather than doing it for food and clothing, for example, as those who hooked mats for the International Grenfell Association (IGA) did, or for pleasure during a long winter, the mat makers did it as a production effort. Some mat hookers were making their own products their for sale or for their own consumption. And there were individuals such as Sister Ann Ameen, who hooked mats with truncated biblical messages and inspirational sayings, and sold them from her home (Fig. 7 and Fig. 8). But in Placentia Bay West, mat making was a business. Mats would be sent to shops or to the St John's craft fairs, and eventually, to wholesalers outside the province. By the mid-1980s, Placentia West Mat Makers were selling their wares — hooked mats in several sizes, and tea cosies—in craft fairs in Newfoundland and beyond. Several of the mat makers travelled to England and gave demonstrations of rug hooking; their mats were on display in England and at the National Museum of Man in Ottawa (now known as the Canadian Museum of Civilization, and located across the Ottawa River from Ottawa in Gatineau, Quebec). The craft industry was alive and well, thanks to input from "outsider" knowledge.

12 The word industry reminds one of both the IGA and the southern Appalachian crafts revival of 1930-40. Being cognizant of the effects of historical and social economic factors on the development of trends, I will examine events in Newfoundland in the 1970s with a view to craft production at places like Berea, Kentucky and Asheville, North Carolina.20 For, while I am not suggesting that conditions for Newfoundland women in the 1970s were as harsh as the conditions of people in southern Appalachia during the depression, there are interesting parallels. The initiators of social change often have roots in the middle classes. In the case of America, early twentieth-century figures such as ethnomusicologist Frances Densmore come to mind; she was concerned with collecting the endangered traditions of those who had formerly been referred to as "savages." In England, William Morris was similarly aware of preserving tradition. He saw the preservation of folkways as an alternative to "mass production and other alienations of industrial capitalism."21

13 What was eventually realized is that good intentions do not always accomplish the desired goals. Home production does not ensure fare wages (this was demonstrated locally in 1983: in Not for Nothing, a study on wage disparity among low-earning and unemployed women in Newfoundland and Labrador, whose results were communally published, women working in craft production were said to be earning from a third to a half of the minimum wage).22 The Arts and Crafts movement in England was more of a socio-economic cause, a critical voice; harsh questions were being posed by its leaders, Morris and John Ruskin. But they were of the middle classes and could afford good taste and simplicity; they could afford not to be part of a capitalist economy. Sometimes, good intentions are thinly veiled attempts to prettify a sordid picture. Even though there was crushing poverty in the United States, the crafts revival movement was actually about aesthetics; those who profited were not those who produced the hooked rugs or baskets. Intellectuals like Jamas Agee might have bemoaned the loss of tradition all they wanted, but the reality is that, then and now, aesthetics are big business. That is why the Appalachian mountain crafts sold so well: "consumers were purchasing more than a newly conceived good.. .they were purchasing an icon of an imagined past, provided by a group of contemporary citizens who had assumed the task of preserving a carefully selected version of the nation's heritage in the present."23 Both Gerarld Pocius and Dell Hymes have written of the need to traditionalize a past that is, in reality, quite unromantic.24

14 Jane Becker notes that the combined effects of "taming the savage" (as was evident in Victorian morality/tastes/love of collections), museum displays and nostalgia created "a niche for southern mountain products that helped redefine both their meaning and the relationship of their makers to the larger culture of industrial America.25 This brings us back to Glassie's notion of consumerism and consumption. As already noted, the artifact, in this case, a hooked rug, is communicated from creator to the consumer. "Consumption, like creation, collects contexts in which the meanings of the artifact consolidate and expand.. .the consumer's reaction overlaps with the creator's intentions."26 As we saw with Lynda's mat there are many contexts in consumption: use, preservation and assimilation. The mat was taken home, brought to a specialized cleaner and now rests in Lynda's bedroom, where it reminds her of her Newfoundland holiday; she is still deciding whether to hang it on her living room wall. And it connects her to her childhood days in the hunting lodge, memories of an idealized past.

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5 Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 6 Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 7 Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 815 I have described briefly both creators and consumers. I will now discuss how "contexts of communication connect the two, balancing creation against consumption, enfolding their similarities and differences," for as Glassie says, this is where meaning has its centre.27 Predictably, the meaning varies as radically as the contexts of communication. The job of the ethnographer is to ascertain that meaning: in my interview with the director of a crafts centre, I might find a meaning that is at variance with the story of one former volunteer of Placentia West Mat Makers who just could not afford to work for low wages. Similarly, my research involving a museum curator will reveal a different view than the views of under-waged women in the crafts field, even though the contextual time, 1980-82, is similar. And I can easily imagine that the unknown creator of Lynda's mat would be aghast at the amount of money that was spent on a mat made to cover the floorboards.

16 Going back to the Arts and Crafts movement in southern Appalachia, one can see how actual meaning deviated radically from the intentions of the reformers, who were striving for "a healthy civilization" and "modernity."28 People such as Allan Eaton (1878-1962), who had arts, government and social issues in his background, might have had honourable intentions in promoting handicrafts as a way of preserving rural life. To him, crafts were symbols which could "reflect folkways, bring city and country dwellers into closer touch, and interpret the people of different areas to one another."29 As such, Eaton, in his work at the Russell Sage Foundation, organized exhibitions of mountain crafts; he hoped the success of crafts exhibits would improve as the consumer tastes of the American homemaker improved.30 The masses would need some educating.

17 Along the way, of course, there were disconcerting issues like the appallingly long hours that "the folk" had to work to produce their quilts, baskets or rugs. Stories of backbreaking work and tedium are detailed in Becker's Selling Tradition; as the incorporation of craft practices into mainstream life continued, it is clear that capitalist consumerism would lead to the fate of domestic craft production. By the end of the 1930s, the connection to "an idealized past" had shifted focus "away from the processes of creation and production and the meanings and uses of handicrafts in local culture, to center on the products themselves.31 " This sounds eerily familiar in the current study of crafts production in Newfoundland and Labrador. I am reminded of the adoption of the non-traditional Inuit imagery by those directing Labrador craftspersons and the later reproduction of these designs in mass-produced parkas.32

18 In 1983, the Women's Unemployment Study Group noted that working at craft production was seen as a last-resort job because the pay was so low. At that time, women made up "most of the 2500 or more producers" selling their crafts in Newfoundland and Labrador; they were usually knitters.33 The work was an alternative to unemployment; it could be carried out at home, where children could be cared for as well. Ever since the days of the Depression, organisations such as the IGA and NONLA. (Newfoundland Outport Nursing and Industrial Association), have engaged in cottage-industry enterprises such as mat hooking and knitting.34 Back then, they paid women a small wage for their craft production skills. In 1983, these agencies, which were still in existence, were still paying low wages. Craft producers lacked control over production and marketing and the whole industry was facing competition from mass-produced goods. The only people who can afford to buy expensive crafts, once the middle-man has been figured in, is the middle class buyer. So it is not surprising that the creator becomes alienated from her creation. She cannot afford to create!

19 I have discussed contexts of creation in which people's incentives are both personally and financially motivated. Similarly, contexts of consumption involve consumers with good intentions and social consciences as well as those who crave either the best buy or the best acquisition (sometimes, in the art world, price unites with acquisition to become the end goal eliminating anything as mundane as taste). Contexts of communication have the greatest discrepancy in meaning; multiple meanings vary from agency to agency. I last tread the path of craft development with the Placentia West Mat Makers in the early 1980s. They were now making mats with designs that would have meaning to both people from the province and visitors from "outside;" Nelson Graburn might argue that they were developing "souvenir" arts and crafts, that is, mats that did not have traditional designs decided upon by their creators and by their peers in the community but, rather, by some production committee (Fig. 9).35 However, as Graburn has noted, tourist art can lead to "the revival or continuation of some arts that are faithful to traditional styles and genres."36 Sales of Placentia West mats may have stirred interest in rug hooking. Traditional mats were still commanding attention.

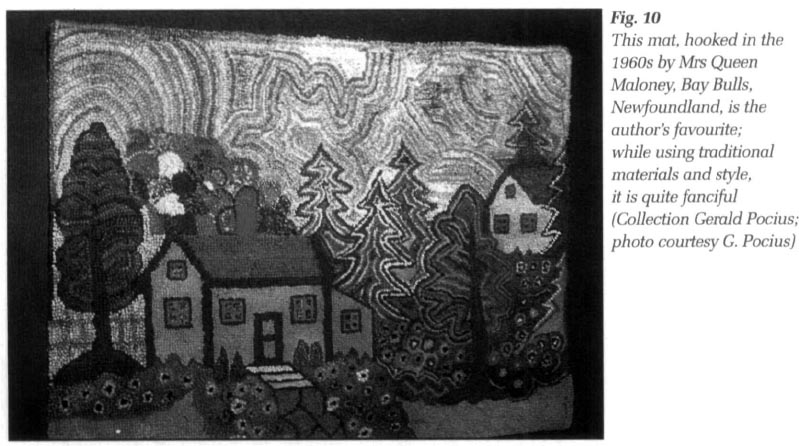

20 At the 1981 annual meeting of the Craft Council of Canada, held in Newfoundland, the keynote speaker, Gerald Pocius, discussed hooked mats made by Mrs Queen Maloney, a well-known traditional mat maker from the Southern Shore community of Bay Bulls (Fig. 10).37 These mats had always been made with function in mind. It seems that, with production, mats were moving away from function and moving towards other meanings; the contexts of consumption were expanding. In 1982, the Atlantic caucus of the Craft Council of Canada produced a glossy catalogue of awards in which hooked mats from Newfoundland were featured. Winners from Placentia West exhibited in both "non-functional object" and "household textile" categories.38 By the mid-1980s, the Placentia West Mat Makers had wholesale clients; they were attending craft fairs and displaying their mats.

Display large image of Figure 9

Display large image of Figure 9 Display large image of Figure 10

Display large image of Figure 1021 One exhibition venue was the Canadian Museum of Civilization. I thought it rather odd that the museum would choose to display the re-invented tradition of rug hooking, as opposed to traditional mats made by individuals like Mary Margaret O'Brien from Cape Broyle on the Southern Shore. Perhaps the mat makers displayed both the traditional block and floral designs, as well as the more "souvenir"-designed mats?39 The Placentia West Mat Makers were now run by a managing committee; profits after expenses went to the mat makers. Government agencies like the Department of Rural Development and as well as NLCDA, which was run by the crafts persons themselves, apart from a paid director, found that by 1985 the crafts industry was working with a tighter budget. Not only were women moving away from hooking mats as enjoyment but they were moving into the position from which mat making had formerly freed them. Traditionally, hooking mats was seen as a respite from one's household duties; it was something to enjoy for oneself. Now, women were once again becoming constrained by an overseer.40

22 In doing my research, I found that in 1988 the Department of Rural, Agricultural and Northern Development in the Progressive Conservative government in Newfoundland and Labrador sponsored a thick craft directory'. Production enterprises such as Placentia Bay West were selling their mats and tea cosies, and advertisements for crafts suppliers and businesses were included. It is telling that the craft directory for 1991-92 is a much thinner product. By 1992-93, the craft directory was sponsored by Enterprise Newfoundland and Labrador, Cottage Industry Division. However, by 1994 the directory was a large format, full-colour 32-page gift and apparel catalogue; it was sponsored by "a Rural Development Cooperation Agreement between Enterprise Newfoundland and Labrador Corporation and the Federal Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency" (Fig. 11).41 It came complete with a message from the Liberal Minister of Tourism and Culture. This is further evidence of the commodification of the craft industry. One wonders to what extent the crafts industry was connected to tourism at this stage. The input of a certain budget could result in a much greater return in the future. One needs to examine the changing governmental policy as the players change. Commodification would have ramifications for the traditional art of mat making.

23 The Labrador Crafts Producers Association was formed in the mid-1970s "to act as one voice for the local craft councils spread along coastal Labrador;" by 1991, Great Northern Peninsula Crafts was established.42 It was a joint venture of the Great Northern Peninsula Development Corporation and the Straits Development Association. It is clear that, by now, craft production across Newfoundland and Labrador had a high degree of organization and was increasing its business acumen. NLCDA, which had had résumés of its crafts producers and applicants for membership since the 1970s, was endeavouring to maintain high production standards. In 1993, Anne Manuel became Executive Director of NLCDA; in a November, 2003, interview she told me that the high standards that are demonstrated by craftspersons now were achieved through peer-assessment, increased business skills and constant review of quality control. Volunteer committees and jurying groups have, over the years, ensured high product standards. But as mat-maker Edna Kelly told me, it is difficult to remain the volunteer committee head of a production group, when one must travel long distances each day, adding vehicle costs like gasoline to already unrecompensed hours of work.

Display large image of Figure 11

Display large image of Figure 1124 In 1994, A Handle on the Past, a compilation of research on craft design in Newfoundland and Labrador, was assembled in a report by Colleen Lynch for the Craft Development Division, Department of Tourism and Culture. The year 1994 seems to have been a very good one for both crafts and tourism, if publications are anything to go by! Government, business and crafts were forming stronger alliances. This would have repercussions for the unaligned craft producer trying to go it alone.

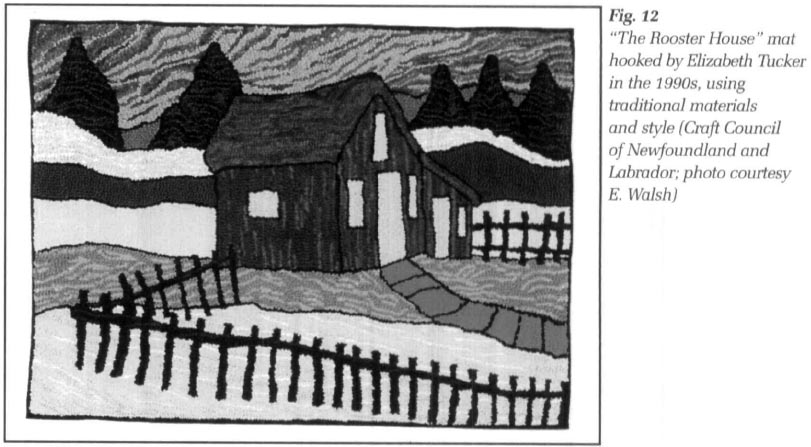

25 In 1995, mg hooking took another curve in its path of development. The Rug Hooking Guild of Newfoundland and Labrador (RHGNL) was begun by Linda Peckford, after contact with another rug hooker from New Jersey. Elizabeth Walker, who had visited the province in 1994. Peckford "made phone calls and wrote letters and eventually gathered twenty-three women from the province for a weekend of rug hooking in the Change Islands [on Newfoundland's northeast coast]."43 The guild had 85 members by 1996; the membership now is approximately 125 and groups meet in three or four centres across the island, although the majority of members live outside St John's. Membership is "open to anyone interested in preserving the traditional art of rug or 'mat hooking' as it is called in this province."44 There are two facets of RHGNL that interest me: one is the school connection (classes or workshops are taught in classroom settings). The second aspect is the emphasis on the preservation of tradition. This veers off the path of mat hooking as production; it seems less commodified on the one hand, yet one must charge fees for teachers, so there is some commodification. In spite of this commodified aspect of charging for courses, the guild does seem to be hooking mats for the pleasure of it; they hold "hook-ins," during which middle-class women sign up and hold what sounds like old-fashioned quilting, or hooking, bees.45 In following the literature on guild membership, I discovered that the Member for the Avalon area is Elizabeth Tucker, a person whose hooked mats command up to two thousand dollars each (Fig. 12). As an interesting aside, when I remarked to Isabella St John on the price tag for Tucker's work, St John said, "Oh, so she's getting paid $10 per hour now— great!"46 I was quickly reminded of just how little recompense craft work generates for its creators.

26 Further teaching approaches to arts and crafts were established in the 1990s. In 1994, the textile studies centre of Cabot College in St John's was renamed for Anna Templeton, a Newfoundlander who had been trained in domestic science in the 1950s. The Anna Templeton Centre now has an advanced textile arts program. Sir Wilfred Grenfell College (named for Dr Wilfred Grenfell), an affiliate of MUN, in Corner Brook, now confers degrees in fine arts. It is fitting that these programs are taught at institutions named for individuals who played large roles in the development of traditional arts and crafts in this province. Both educators had "outside" connections or training, the former in Montreal and the latter in England. But what does all this education in traditional skills such as mat hooking or skin boot making mean to the person who either cannot afford, or is disinclined to avail of organized courses? If those practising traditional skills are not given their "voices," those arts are in danger of dying out.

27 In 1996, the booklet Whew It's At—A Guide to People and Places on the Great Northern Peninsula and in Southern Labrador featured an article on Margaret Manuel of St Lunaire-Griquet. In her seventies, she "spen[t] hours each week sitting at her kitchen table, hooking mats which she s[old] to Grenfell Handicrafts' ' and was shown in a photo with one of her mats; "some of the scenes depicted on the mats include[d] dog teams, polar bears and rural settings."47 These scenes were almost certainly dictated by those who directed production and were not of Mrs Manuel's choosing. Once again, commodity was overlapping tradition. This raises the question "Can one continue tradition when one is engaged in production?" The southern Appalachian experience proved otherwise; I think the same is true in our province. Once one separates the creative and the communicative context, and the creative is aligned wholly with the consumer context, tradition is lost or, at best, it changes.

Display large image of Figure 12

Display large image of Figure 12 Display large image of Figure 13

Display large image of Figure 13 Display large image of Figure 14

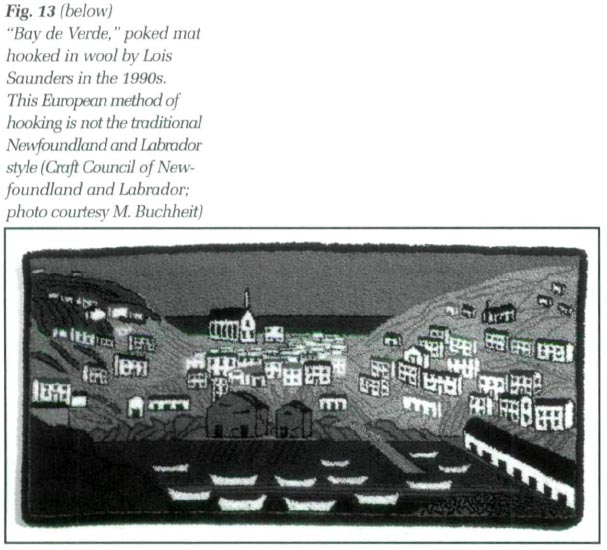

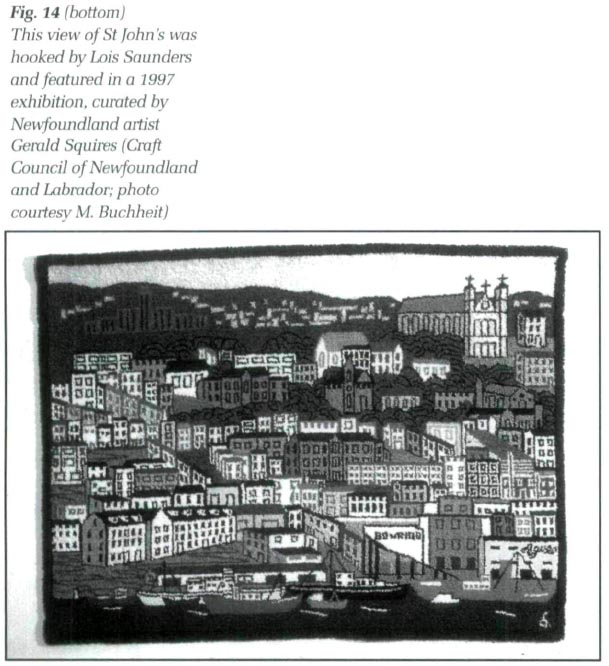

Display large image of Figure 1428 In 1989 Lois Saunders, who in 1980 helped to organize mat makers in Placentia West, began to hook rugs. Instead of using the British Isles technique that is used by most, Saunders used the punch technique, which is of European origin. Instead of pulling, one uses "a sort of fountain pen" to thread through wool, not strips of cloth. The backing for the mats is monkscloth, a much more regular and finer weave than burlap (or brin, as it is called in Newfoundland).48 Saunders did not adhere to traditional floral designs or geometric patterns; she hooked mats with local scenes such as "Trinity Church" or "Branch," communities on the east coast of Newfoundland (Fig 13). By 1994, she had developed her own rug hooking company, Drogheda Mats, and was selling her mats, adaptations on a traditional art, in the gift and apparel catalogue, which has been discussed above.

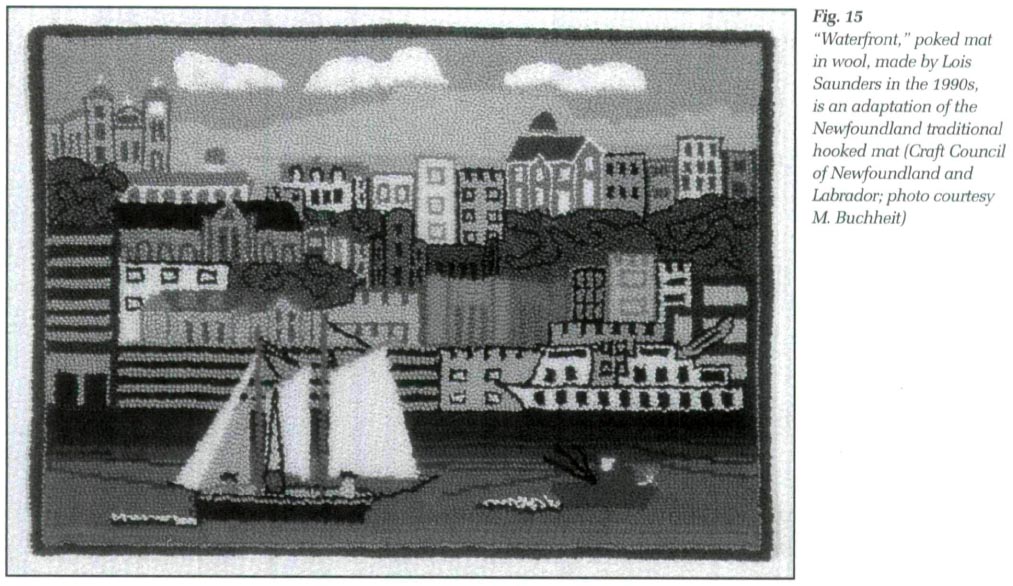

29 Saunders' later work was featured in an exhibition presented at Devon House Craft Gallery, St John's. It was co-ordinated by the Newfoundland and Labrador Crafts Development Association and curated by Newfoundland artist Gerry Squires. In an NLCDA-released biography of Saunders, it was noted that "Saunders' mats are in the collection of the Art Gallery of Newfoundland and Labrador; Government House, St John's; Canada House in Ireland; and, the offices of the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans in Ottawa" (Figs. 14 and 15).49 Hence, the adaptation of traditional designs, forms and styles: like many craftspersons, Saunders uses adaptation and commodification to continue the "business" of tradition. One wonders whether traditional craft skills, such as mat hooking, becomes art only if the arbiters of the craft industry decide so?

30 In 1999, The NLCDA changed its name to the Craft Council of Newfoundland and Labrador. From their mansard-style building at historic Devon Row, St John's, they operate a pottery studio, art and craft galleries, and administrative offices. Devon House Craft Gallery also runs one of the largest gift shops in town; the items sold must pass stringent quality control parameters, as defined by the craftspersons themselves through jurying boards. In my interview with Executive Director Anne Manuel, we discussed ideas of souvenir art, art as opposed to craft, and art versus function.50 The traditional mat, she noted, was "up to twenty-five years ago, a functional object...you put them on the floor to keep your feet warm, not on the wall....as [artist] Gail Squires says, 'Function first and art wherever you can fit it in'."51 Mat makers like Louise Belbin created more primitive mats than others. That same primitive quality is now often the very factor which makes a mat a desirable commodity (just as the idiosyncratic nature of Sister Ameen's mats makes them desirable). But being considered primitive is itself a constraint imposed by the higher classes on the lower ones, who, in reality, did not practise self-censoring. Mats made according to production-line design are made according to traditional style but are adaptations. Manuel agreed they are more "tourist items," like the souvenir art of which Grabum wrote: unlike the traditional arts which help "maintain ethnic identity and social structure," "tourist" art is "made for an external, dominant world" and is often "despised by connoisseurs as unimportant."52

Display large image of Figure 15

Display large image of Figure 1531 In our discussion on art versus craft, I read the postcard (which is how the Craft Council of Newfoundland and Labrador advertises their gallery shows) announcing "an exhibit of hooked rugs," which "echo traditional techniques."53 One of these mats made by Elizabeth Tucker is displayed at the gallery in Devon House and is selling for $2 000. I have seen traditional mats at antique shops selling for $100-$400. When I ask the rhetorical question, "What makes this mat worth $2000 and Mrs B's $400?", Manuel replies, without missing a beat, "What makes it $2000 is that there's somebody willing to pay for it!54 Manuel sees the distinction between what is art and what is not as "a very fuzzy area, [one] not worth wasting breath over, as it doesn't matter; it's up to yourself."55 Unfortunately, it does matter if one is relying on selling one's craft to pay the bills. Howard Becker, in his book Art Worlds, devotes much discussion to the distinction between craft and art. It often is a matter of whom one has in mind as one's audience that decides whether one is constrained in one's creation. Traditional mat hookers were not constrained by their audience, for they were producing for themselves; colours and design were a personal choice. Once one is producing for an outside audience, especially in an employer-employee mode, then one must let art give way to craft (wherein technique, style and design might be decided by others). Hence, we have the dichotomy of craft production, about which Millie Creighton writes:

32 I agree completely with Manuel when she says that the distinction between home-knit socks with a red band, the mats made by Elizabeth Tucker and the art of Christopher Pratt all share one thing: as art, it is difficult to draw a line and "if there is a line it's a horizontal line."57 Howard Becker notes that change usually decides what is art and what is craft: "the histories of various art forms include typical sequences of change in which what has been commonly understood and defined by practitioners and public as a craft becomes re-defined as art or, conversely, an art becomes re-defined as a craft."58 But I do not agree that it is all in the eye of the beholder; rather, in the crafts industry and in the art-world, someone becomes the master of connoisseurship and can dictate just how high the line is. Value is determined by socio-cultural and socio-economic standards. These standards are often set by those in positions of power who decide what the extrinsic/monetary determinants are. If those in power decide that an object is deemed of value, then it suddenly acquires "value," which is rather arbitrary. Crafts as well as art can be subjected to what Howard Becker calls "the institutional theory of aesthetics."59 Instead of focusing on "something inherent in the object to a relation between the object and an entity called an art world," we can give some structure to what is considered art (such as artist Marcel Duchamp's signed shovel); but we risk the exclusion of those makers of traditional objects who do not rate in the upper echelons of the craft movement.60

Display large image of Figure 16

Display large image of Figure 1633 Being of "value" still does not make an artifact art. Larry Gross writes about art as a communicative act (and I think the same can be said for craft) or event "involving a source who encodes a message that is decoded by a receiver, in the case of the arts each of these terms takes on special properties: an artist creates a work of art that is appreciated by an audience."62 If the source who encodes a message has it decoded by the right receiver, then one is off to the races. But the art world is similar to the stock market in that each is a risky and flippant business, determined by the fluctuations and whims of society (or those who have enough "pull" to decide that, for example, Duchamp's urinal is art). As the narrative changes or evolves so do the extrinsic values of objects. One needs to keep sight of the multiple meanings of things. Every object has a text which can be read in many contexts. Artifacts which might have one function to a creator, such as Mrs O'Brien's foot-warming mats, are, in reality, multifunctional. Some of these functions are instrumental; they are made to use. But they are also made to decorate, to give as gifts, to buy food, to pay for a new kitchen chrome set or even to spread the message of salvation (Fig. 16). They represent different things for creator and consumer. Robert Merton's idea of latent functions envisions unforeseen consequences: little did the Labrador coastal woman who made her mat to buy clothes (wherein the mat is a sign of poverty) foresee the day when her mat would hang on a socialite's wall (wherein the mat is a sign of conspicuous consumption).

34 Signs change with the changing times, Glassie notes that creation entails use.63 If the context is "sexed up" by association with those in positions of power, as was the case with Phyllis George Brown's "discovery" of Kentucky's craft traditions in the early 1980s, then the extrinsic value of an artifact multiplies.64 Glassie's idea of art seems to place greater emphasis on intrinsic value: "Where use meets beauty, where nature transforms into culture and individual and social goals are accomplished, where the human and numinous come into fusion, where objects are richest in value there is the center of art."65 The person with the highest status is not the one with the most expensive mat. Rather, that person is the mat maker who is most contented with her lot, or that person whose feet feel better for being warmed, or that person who has transferred her knowledge to others. Goods and commodities will only last so long; satisfaction, like self-esteem, can grow and grow even as the outward world evolves. Glassie speaks of hope while I speak more of confidence. Both are invaluable.

35 In my interview with Anne Manuel, she noted how difficult it is to "find anyone who is making a functional hooked mat these days."66 I think function is defined as how you use something; if I want to keep my feet warm, does it really matter if something is "meant" to be on the floor or on the wall? If the Placentia West mat maker, Edna Kelly, who formerly volunteered her services as an area representative finds she can make more money as a clerk and, therefore, spend more time with her family, why should she continue to make traditional crafts for pay? If the imagined past involves living off the avails of someone else's efforts, for which they are not being fairly or adequately recompensed, then maybe we should all be happier not to live with good taste and simplicity, which was espoused by Morris. And as for those who are willing and able to spend the big bucks for a connoisseur's artifact, more power to them, let them support the arts and those artisans who can still afford to create. It is quite possible to be dragged into the commodifier's web of only one line, a vertical line, with art at the top and craft at the middle and pure function at the very bottom.

36 I would prefer that we not lose our hold on reality and get lulled into thinking that yesteryear was a much simpler and gentler time; it was not and today is not. The reality was, in a world ruled by what we Newfoundlanders would know as the merchant classes, people strived to cope with the harsh realities of life by creating symbols of meaning. These objects reflected the belief patterns not only of the individual creators but also the "belief patterns of the larger society to which they belonged."67 By 1965, things had not changed much in southern Appalachia: craftspersons were told "you have to forget yourselves."68 If our present society is one in which social justice has been eroded and "deliberate amnesia" is practised in the area of labour equity, then we have not learned anything.69 How can we expect people to find meaning when "invisibility and amnesia [contribute to] the dissolution of personal histories."70

37 Lynda will likely continue to collect hooked rugs; may she continue to like them for what they are, happy connections with her past and her present. Hooked mats do not have to be texts of an unjust past. More importantly, for the continuation of the practice of traditional skills, I hope that there continues to be an arena in which those skills can be appreciated for what they are: metaphors made by their creators.

I would like to thank Anne Manuel, whose input was quite valuable to the writing of this paper. Thanks also go to Lynda Yolland, Edna Kelly, Isabella St John and Margaret Angel. I wish to acknowledge the passing of Lois Saunders, who contributed much to the development of the crafts industry. Lois died 5 March 2004, after this article was written.