Articles

Forget-Me-Nots:

Victorian Women, Mourning, and the Construction of a Feminine Historical Memory

Abstract

A study of the Royal Ontario Museum's mourning collection suggests that middle- and upper-middle-class Victorian women used the rituals and accoutrements of this practice to establish and disseminate a meaningful feminine identity and accessible historical memory. Through the transformation of their homes and bodies into sites of memory in honour of friends and family, women were able to realize a myth-making space outside of formal, public commemorative rituals and male-dominated historical discourse. Mourning customs also served as a feminine ritual that allowed for the validation and transfer of women's traditional skills, knowledge, and sense of self In the process of exploring the shifting meanings of mourning objects in women's lives, particular attention is paid to the experiences of Canadian women.

Résumé

Une étude de la collection sur le deuil du Musée royal de l'Ontario suggère qu'à l'époque victorienne, les femmes des classes moyennes inférieure et supérieure utilisaient les rituels et attributs de cette pratique pour établit et diffuser une identité féminine significative et une mémoire historique accessible. En transformant leur foyer et leur corps en mémorial de leurs proches, les femmes étaient en mesure de créer un espace mythique en dehors des rituels publics officiels de commémoration et du discours historique à prédominance masculine. Les coutumes de deuil servaient aussi de rituel féminin permettant la validation et le transfert des compétences traditionnelles, des connaissances et du sentiment d'identité des femmes. Le processus d'exploration des significations changeantes des objets de deuil dans l'existence des femmes accorde une attention particulière aux expériences vécues par les Canadiennes.

1 In his analysis of hall furnishings in Victorian America, Kenneth L. Ames remarks that "the commonplace artifacts of everyday life mirror a society's values as accurately as its great monuments."1 The following study will extend this analogy further, for it seeks to demonstrate that for middle- and upper-middle-class women in the Victorian era, the material culture of the "home," in this case the sentimental objects and highly-stylized garb associated with the ritual of mourning, were their great monuments, a means of preserving and communicating a meaningful past.2

2 Given the recent flurry of research activity in the areas of museum representation, material culture and memory, as well as the ongoing interest in recovering the intricacies of women's pasts, it would appear that the intersection of these fields would be a highly relevant area of study. According to Alon Confino, the simplest way of defining memory is "the ways in which people construct a sense of the past."3 Institutions such as the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) play a crucial role in coalescing, constructing, and maintaining the historical narratives that people experience and understand. Yet, these visions of the past are in turn dependent upon the material remnants that are preserved and celebrated within these sites. As a result, a close examination of the "things" that shaped people's lives enables the material culture scholar to discern and reveal the secrets, the insights and lessons about the past, that are contained within these artifacts.

3 Entranced by the Victorian "celebration of death" which scholar James Stevens Curl characterizes as "touching, pathetic, and rather absurd," I decided to pursue an analysis of the ROM's mourning collection as well as the accompanying catalogue records.4 In part, I was driven by a desire to move beyond the traditional notion of mourning as a mechanism for controlling women after the deaths of their husbands or fathers as well as a means for displaying the wealth and social status of the deceased's family. The ROM proved to be an invaluable resource in investigating the meaningful role played by the rituals and accoutrements of mourning in the lives of Victorian women. The objects considered during the preparation of this paper, and from which my questions and conclusions emerged, run the gamut of artifacts associated with death and mourning and are English, American, and Canadian in origin: an evening dress and belt; a bonnet with weepers; silk and linen veils; rings; brooches; bracelets; a calling card; a handkerchief; and touchingly lovely samplers. What, then, do these objects tell us about the past?5

4 This essay hopes to explore the nature and meaning of the ROM's contemporary collection of mourning objects within the context of the changes and continuities, assumptions and expectations, of the status, role, and identity of middle- and upper-middle-class Victorian women, in particular Canadian women, and their involvement in historical commemoration. In essence, it will investigate the accoutrements of mourning as part of women's purposeful efforts to act as myth-makers and memory banks in a world in which their lives and identities were largely defined by the nexus of home and family. I will argue that as well as providing a tangible memorial of their "beloved," Victorian mourning artifacts offered women a means of creating a particularly feminine historical memory that allowed them to preserve and interpret their stories, and those of their families, while engendering and transmitting a meaningful sense of identity and social role.

Women, History and Commemoration During the Victorian Era

5 To understand Victorian mourning practices, it is necessary to briefly explore the early efforts of middle- and upper-middle-class women to claim a unique voice in the realm of historical writing and commemoration — their desire to recover, remember and thereby validate the past lives of women and other "ordinary" people. During the early to mid-nineteenth century, public history and commemoration was largely the domain of elite males who sought to preserve a self-serving vision of the past while attempting to professionalize the discipline they studied and taught. According to historian John R. Gillis, commemorations in the nineteenth century were "largely for, but not of, the people. Fallen kings and martyred revolutionary leaders were remembered, generals had their memorials, but ordinary participants in war and revolution were consigned to oblivion."6 This led to an historical iconography that celebrated the dramatic achievements of heroes. Visual imagery, such as monuments, were a powerful tool in crafting not only a masculinist conception of history, but also in denning and transmitting notions of manhood. In Canada, the romantic cult surrounding General Brock resulted in the erection of a monument to the warrior hero at Queenston Heights in 1824.7

6 As Gillis indicates, women were largely excluded; their history was forgotten or ignored by these national, public commemorative practices. As discussed by Cecilia Morgan, the role of women in the War of 1812 was downplayed or ignored in favour of the image of the "helpless Upper Canadian wife and mother who entrusted her own and her children's safety to the gallant militia and British troops."8 As a result, the first memorial in honour of a Canadian woman, a bust of Laura Secord erected at her grave site in Lundy's Lane battlefield cemetery, did not occur until 1901. Similarly, historian Norman Knowles indicates that, as they were public affairs involving "important social and political questions," women were not represented as speakers or organizers during the 1884 centennial celebration of Ontario by the United Empire Loyalists held at Toronto and Niagara.9 When they were represented in memorials, women were conceived of in allegorical terms — for example, the female figure of the Statue of Liberty became the emblem of national identity. Instead, women were expected to be the nation's chief mourners who were responsible for remembering the men.10 As discussed by Harvey Green, the patriotic histories that were written by male historians described events and accomplishments that women could admire but never aspire to realize.11

7 Despite the tenuous relationship between women and public forms of commemoration, as well as their exclusion from the conventional historical narrative, which stressed major events and great men, female historians attempted to re-imagine and re-assess the value and message of the "past" through their use of the pen. In the mid-nineteenth century, women sought to become involved with and legitimate their participation in history-making through the appropriation of masculine historical forms. According to Billie Melman, this represented the "classical period" of women's history. In claiming a place for the "great woman" story, female historians invented a tradition of feminine biography that told the stories of illustrious women or "women worthies." In writing about exceptional women, those "queens, heroines and noblewomen whose lives had intersected in some definite way with the male-dominated political realm," female historians established the validity of a female historical subject and demonstrated their ability to move beyond their designation as "rememberers."12 Historical biographies with titles like "Life of Isabella I, Queen of Spain" proliferated in ladies' periodicals like Godey's Lady's Book.13 In Canada, the writer, women's rights activist, and ardent patriot Sarah Anne Curzon, promoted a vision of Laura Secord as an emblem of idealized white Canadian womanhood in her 1887 play Laura Secord: The Heroine of 1812. Ennobled by a sense of mission, these popular stories sought to provide valuable life lessons, and spurred on by new concerns for women's rights, these women sought to convey the righteousness of telling the unwritten, yet very real, story of heroic women who "had played a significant role in the development of their national and local communities."14 In the process, they made these women an important part of public historical memory.

8 Despite this emphasis on "atypical women," it was within the role of "mourner," and through their identification with the "domestic" past of their friends, families, and female forbears, that women were able to negotiate a novel place for themselves, and other ordinary people, within the public expression of the historical imagination. Middle-class female historians developed a distinctively feminine approach to history that possessed an emotional content and moral imperative in that it "redeemed" who and what was "discounted as waste by professional historians."15 And, these women relished their newfound role. In the United States, women were active participants in the 111 historical societies that existed in 1860.16 In Canada, some women, such as Janet Carnochan, who presided over the Niagara Historical Society, occupied positions of leadership. However, most women assumed auxiliary or supportive roles within historical societies. As a result, some women established female-only organizations, such as the Women's Canadian Historical Society of Toronto (WCHST).

9 In an effort to proclaim ordinary people to be objects worthy of study, women wrote detailed genealogies, biographies, local histories and memoirs. These histories reflected the evangelical Christianity espoused by many of these women by asserting that every life was worthy of commemoration. They wrote extensively about local social, cultural and domestic history, describing the everyday experiences of settlers and their families — their homes, dress, and habits — in exhaustive detail.

10 Even when they wrote books about important events, such as Elizabeth Stuart Phelps's account of the Civil War entitled The Gates Ajar, many of these historical authors addressed sentimental female concerns of love and loss; they focused upon the "insignificant" people and the way that these occurrences impacted family life.17 The men in these histories were defined by their domestic roles. They were presented from the feminine perspective and recognized for their status as husbands, fathers, and brothers, not as public men. Similarly, dates were secondary; life was defined by its meaningful cycles and watershed moments — births, marriages, deaths.18 Indeed, for the undistinguished men, women, and children who were recalled within a plethora of fond poems, moving stories, and respectful biographies, their deaths were their greatest achievement; it released them from their earthly troubles and allowed them to reach fulfillment and heavenly glory.19 In part, the stories that focused upon children who died tragically before their time reflected the actual loss experienced by mothers who sought to work through their grief by writing obituary poems with titles like, "Twas but a babe." However, these literary efforts also represent a desire to remember and honour the most vulnerable and unimportant members of society. While some female historians never aspired to be anything more than "compilers," women's historical writing was an attempt to rescue their subjects from oblivion; and by asserting the value of every human life, they validated their own.

An Analysis of the Mourning Collection at the Royal Ontario Museum

11 For most women, even those amongst the supposedly "leisured" middle-class, the avenue of commemoration offered by historical writing was not an option. They lacked the time or polished writing skills, or they feared the repercussions that would result from stepping beyond the bounds of convention and neglecting their domestic duties. Instead, the average woman's historical and commemorative efforts centred around the accessible, socially acceptable, and uniquely feminine experience of mourning the dead. Mourning objects — samplers, brooches, and dresses — recounted the stories and espoused the value of the lives of ordinary people, as well as asserting the power of the female historical imagination over the communication of the family narrative, prior to the ascendancy of female biographers. Within the highly stylized, symbolic, and feminine form of mourning objects, there lay a potent instrument for relaying cultural assumptions and expectations regarding the female role as well as a means of commemorating family and friends, the people who provided middle-class women with a purposeful and understandable self.

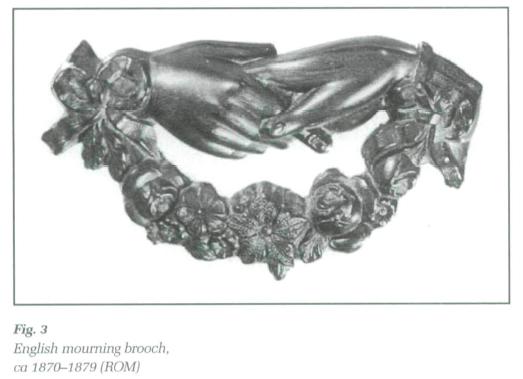

12 In part, the elaborate mourning customs of the Victorian era reflected the aspirations of middle-class women to the cult of true womanhood. According to this feminine ideal, women were to be "angels of the house" denned by their kindness, simplicity of manners, Christian commitment, intelligence, industry, frugality, goodness and generosity. For those women struggling to maintain any domestic order, keeping their home and family clean, fed and clothed, while toiling alongside their husbands in the hardscrabble Canadian colony, this vision of pious and submissive women confined to the domestic sphere was at odds with reality. However, Canada was a nation of newcomers and for a growing number of respectable immigrants, influenced by American and British middle-class literature and lifestyles, the cult of true womanhood was a familiar prescription of conduct that defined whom and what they were or hoped to become.20 As the Canadian middle- and upper-middle-classes grew and assumed a self-conscious identity, with more women living in towns and having hired help to remove some of the household burdens that consumed their day, women had more leisure time to engage in niceties like formal mourning rituals, which demanded that women be ensconced at home for a long period of time.

13 The emergent cultural opinion was that mourning was women's work, they were the memory banks in a society in which men were believed to be more inclined to forget.21 This is evidenced by the fact that all of the objects studied during the preparation of this paper, thirty-four in total, were articles of women's clothing and jewellery — from veils to watch chains — or were samplers produced by women. The absence of masculine accessories of mourning in the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) collection speaks to the tenuous relationship between Victorian men and the rituals of death and grieving. Until 1850, a man's mourning attire merely involved wearing a black mourning cloak (black being the socially appropriate colour for mourning) over his ordinarily sombre suit. After that year, men wore hatbands and armbands of varying widths and for varying lengths of time depending upon their relationship with the deceased. Similarly, while the period of mourning was quite lengthy for women — ranging from six months for a grandparent or sibling, one year for a parent, and two and a half years for a husband — men were expected to return quickly to their public duties. There was little emphasis placed on men transforming themselves into a commemorative sign. As much as men were expected to be virtuous and devoted husbands and fathers, their socially meaningful identity stemmed largely from their "public" activities.

Display large image of Figure 1

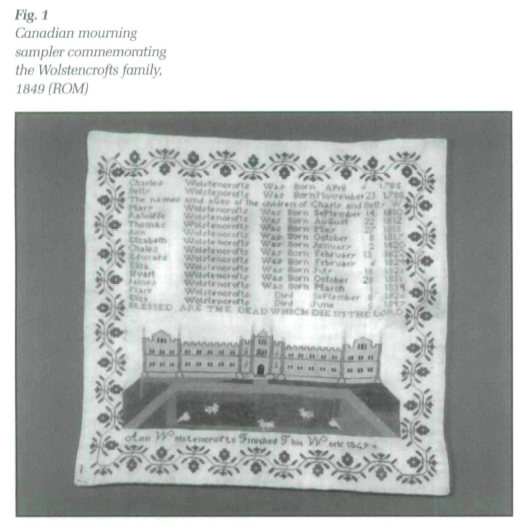

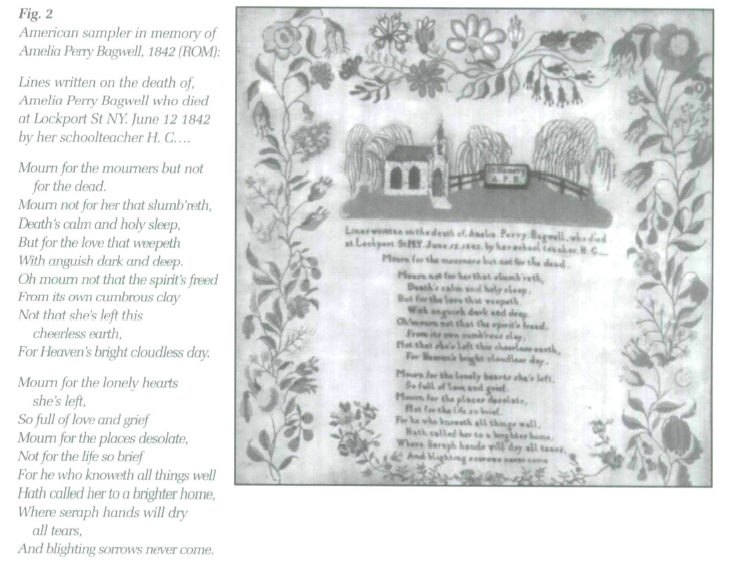

Display large image of Figure 114 As such, the practice of mourning was a vibrant and meaningful "female" ritual, with the associated objects made or worn by women, that transformed the mundane objects of everyday life into powerful and poignant sites for memory. Driven by a "will to remember" that was rooted in a fear of forgetting their family members and thereby losing an essential part of themselves, Victorian women used mourning objects to build a scaffold that supported their sense of a meaningful past; these items provided a "material, symbolic, and functional" site of memory.22 Within mourning rituals, women established two distinct sites of memory: the home and the female body itself. The ROM possesses three mourning samplers: one features a genealogical table of the Canadian Wolstencrofts family (ace. no. 954.111) (Fig. 1); another presents a short poem written by Isabella Torrance in memory of her father, a merchant from Kingston, Ontario (ace. no. 970.184.2); and the final one is a verse crafted by a teacher for a favourite student who passed away in New York state (ace. no. 974.393) (Fig. 2).

15 Samplers that honoured the dead were placed in the most prominent room of the house, the parlour, often along with busts or portraits of the deceased. As well as being the comfortable yet elegant formal gathering space where middle- and upper-class families congregated and greeted their visitors, the parlour was conceived as a type of instructional space, a museum within the home; it was where the family displayed its cultural aspirations and respectability through items like the "étagère," which contained books and decorative artifacts as well as natural objects such as shells.23 A mourning sampler on the wall would accord the deceased with a measure of public recognition and respect while encouraging children to learn and appreciate their family history; it also offered a model of a "good" "Christian" life which they could likewise achieve provided they adhered to the values, traditions and beliefs of their forbears.

16 The ROM's collection likewise indicates the value of the body itself as a site of memory. Women were the stage upon which the experience of the family could be chronicled. In the process, they declared the value of their families' lives as well as their own role in continuing and commemorating the family legacy both as mourners and as "mothers." Within the rituals of mourning, the most ordinary objects were transformed into highly symbolic and significant pieces. The ROM's collection contains two particularly "ordinary pieces" that became infused with meaning through their evocative status: an English black-edged calling card engraved with the name "Miss E. Chamberlain" from 1886 (ace. no. 976.81.19) and a white silk handkerchief with a hand-painted black striped border that dates from somewhere between 1850 and 1899 (ace. no. 963.9.15). Despite the seeming simplicity, the sheer ordinariness of these objects, they hint at a larger meaning. All aspects of a woman's life became a means of commemoration. Their identity of grief and loss infused all of their rituals and activities. Indeed, through the use of a black calling card, a woman asserted that her status as a mourner, her family's experience of suffering, was her very means of identification. It was a lived history in which all of a woman's "things," even the smallest articles of clothing, honoured the past and present stories of her loved ones. "Things" were a loci around which memory coalesced and found meaning.

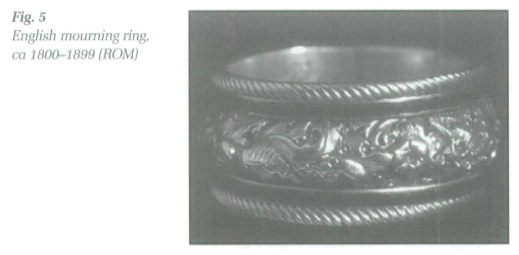

17 During the period of deep mourning, which was the first year of a woman's widowhood or the first six months after a parent's death, etiquette demanded strict social isolation; a woman could not accept formal invitations except from close relatives and was expected to avoid pleasurable occasions and public places. Similarly, women's dress was supposed to indicate womanly modesty and a negation of the self, a desire to grieve quietly and in private, as well as serving as a sign of love and devotion to the memory of the dearly departed. The ROM's collection includes a number of veils as well as a black silk mourning bonnet with chiffon weepers and a brooch at the top of its crown; this headdress would have adequately shielded a bereaved widow or mother from the unflinching inquisition of the public gaze, and hide any falling tears, when it was worn between 1878 and 1905 (ace. no. 994.160.1).

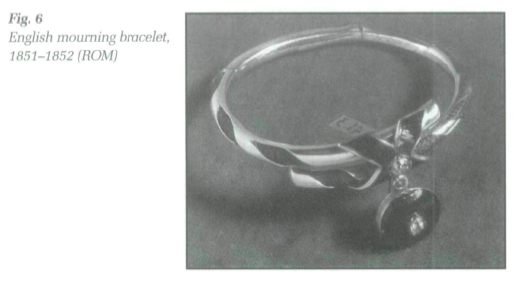

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 218 At the same time, there was an element of spectacle in the use of the female body as a site of memory; indeed, the public display of a woman's sorrow allowed her to transgress the conceptual boundary between public and private. Mourning dress offered women an opportunity to publicly flaunt their respectability and domesticity, that is, their adherence to middle-class codes of feminine behaviour. By drawing attention to themselves and their suffering, women in mourning found a public voice and garnered a respectful acknowledgement of their social and familial identity. They reinforced the ideology and imagery of the cult of true womanhood by appearing in the roles of grieving mother, daughter, or widow. Yet, despite the protestations of dutiful self-denial, when those women who were in deepest mourning went out to church, or received callers at home, there was an unquestionably theatrical element to the impressive, rustling all-black figure: dress covered with crape; bonnet with weepers; fan; parasol; gloves; and jet jewellery. Right down to her black bordered handkerchief, a woman in mourning made a very dramatic, indeed, a visibly stunning statement. This was despite the uncomfortable fit and fabrics and the "drab" "dark" dress with "limited" decoration.

19 In an effort to honour their family publicly, thereby keeping the memory of the dead alive and asserting their special status, some women wore a moderate form of mourning attire for the rest of their lives. Often, they would restrict themselves to the shades of purple and gray or combinations of black and white that were acceptable during the period of second mourning.24 In essence, mourning dress allowed women to be publicly visible, courting the male gaze, without the risk being deigned a dangerous "public" or "loose" woman.25

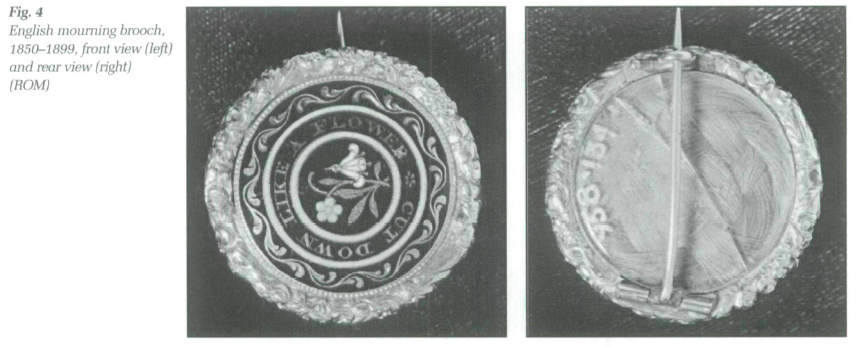

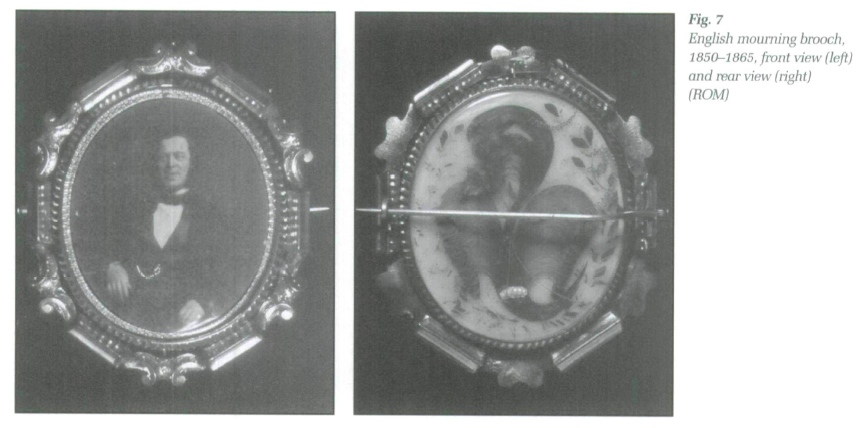

20 The ROM's collection of mourning objects reveals the way in which women established a culturally determined code that incorporated many delicate, "feminine" motifs. Many of the most prevalent decorative designs were quite standardized and appeared on many different objects — for example, pearls represented teardrops. Two exemplary items of jewellery that reflect the feminine essence of mourning objects, and the symbolism of death and sorrow, are found in the ROM's collection. One is a carved jet brooch (the most popular material with which to make mourning jewellery) showing two clasped hands above a floral swag (ace. no. 971.56) (Fig. 3).26 Another brooch features a carved gold rim while its front is composed of gold as well as blue, black, and white enamel; its centre boasts the images of a lily and a forget-me-not, both of which were common symbols of death. This floral design is in turn surrounded by the motto, "Cut Down Like a Flower" and the brooch contains a plait of hair under glass on the opposite side (ace. no. 958.134.1) (Fig. 4). Similarly, the previously mentioned samplers that commemorate the lives and deaths of the Wolstencrofts family and the young student Amelia Perry Bagwell are multicoloured (lots of pink and green) and elaborately decorated; they feature the conventional Christian and domestic mourning imagery of flowers, weeping willows, churches, rural scenes, animals, and idealized homes (Figs. 1 and 2).

Display large image of Figure 4

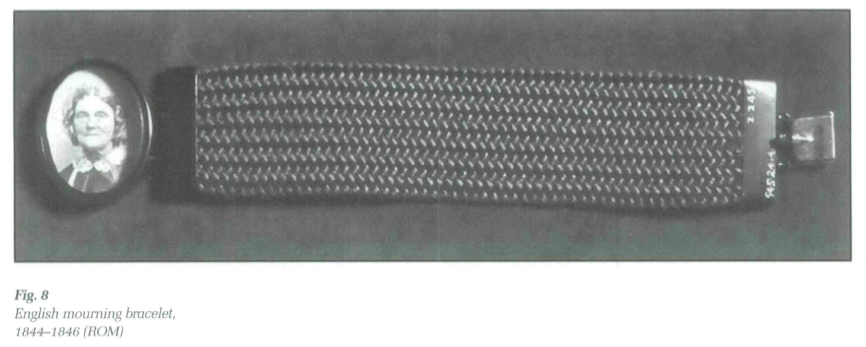

Display large image of Figure 421 The value of mourning as a feminine ritual extended to the very act of creating the objects themselves as this process allowed women to transfer their traditional domestic skills, knowledge, and sense of identity to the next generation through the construction of lasting bonds between them. Arranging hair and working on embroidery together signified and reproduced the close, loving relationship that was believed to exist between mothers and daughters. While carving out a family remembrance, women established a special time and space wherein they could speak freely and identify with other women, expressing their deepest feelings, their hopes and pains. Throughout the nineteenth century, women's lives were intertwined, physically and emotionally, with those of other women. Certainly, there was a tremendous need for a strong female support network to deal with the female cycles of life: pregnancy; childbirth; menopause; sickness; and death as well as to provide much needed help in the home.27

22 Needlework was a powerful symbol of genteel domestic femininity, which would have been transplanted by British immigrants to Canada. The sampler was an initial step in the education of a middle- or upper-middle-class girl and "instructed [her] in docility and accustomed her to long hours sitting still with downcast gaze."28 In a display of obedience, talent, and respect, many young girls prepared memorial samplers for family members they had never known. As embroidery helped beautify the home and the personal belongings that provided comfort to husbands and children, it was deemed to be "correct drawing room behaviour and the content was expected to convey the special psychological attributes required of a lady."29

23 Yet, there was a revolutionary potential to this work. In commemorating their family through the embroidery of a sampler, women, while demonstrating their love for their family in a feminine framework, also asserted the value of feminine talents and claimed their place in the record of the family — their names usually appear on their work. The names of the makers are prominently featured on both the Wolstencrofts and Torrance samplers; however, the sampler for Amelia Perry Bagwell is simply credited to "H. G." (Figs. 1 and 2). This marked the assertion of a woman's voice and her right to engage in a fulfilling and pleasurable activity. Despite her seemingly repressed pose of quiet concentration with "eyes lowered, head bent, shoulders hunched," the embroiderer had the power to engage in an act of memory making by interpreting and expressing the family story through her art.30

24 Similarly, women eagerly attempted to learn how to turn a lock of their loved one's hair into a lasting personal memento. From the 1850s onwards, Godey's Lady's Book offered lessons in hair work, and "do-it-yourself kits" instructing women in how to properly mount the hair of the dearly departed were widely available. While it was always possible to have hair-work professionally done by jewellers, many women were concerned about whether the hair they received back truly belonged to their lost friend or family member. Furthermore, the time and care taken in preparing the hair was a pivotal part of the process of grieving for and honouring the dead. The importance of human hair as a tangible site of remembrance is reflected in the number of jewellery items in the ROM's mourning collection that incorporate it as a central component. However, with the exception of those locks of hair that were inserted into special cavities located inside rings, it is difficult to know what hair-work was professionally done by the jeweller and what was a "home job."

25 Although technological and commercial innovations gradually altered the production and form of these women's crafts, they remained central to the mourning process, and therefore women's construction of memory. There was an increased availability of affordable, time-saving, mass produced alternatives to these types of women's crafts. For example, from the 1870s onward, North American women could cheaply buy pre-printed perforated cardboard memorial cards, which they only had to embroider according to clear instructions in order to achieve a beautiful and touching expression of grief. They could buy plain perforated cardboard if they wished to write their own text and design their own pictures.31 Also, women could purchase mass produced memorial prints, which depicted mourners at a gravestone, or another standardized scene, and which featured blank lines upon which they could record the names and life dates of the deceased.32 While these new products made the traditional skills of women less central to recording the family's history, as well as making them less unique and personal, they made life easier for those women with limited time, imagination, or skill. In the process, they made the role of family historian easier and, therefore more accessible, to women and girls.

26 A textual analysis of the ROM's mourning objects demonstrates how women communicated the stories of their families and close friends, the ordinary people who defined and organized their lives and identities. An examination of three artifacts from the ROM's collection — a ring, a sampler with a genealogical table, and a mourning bracelet — provide insights into the language utilized by female mourners, the lessons they sought to impart. As demonstrated by the English gold and black enamel mourning ring that features a floral design in the centre, the text was often very simple and secondary to the visual statement being made by the object. This ring's primary textual message is the name of the individual being remembered; the inside of the band is inscribed with the short phrase: "In Memory of Thos. Lowe" (ace. no. 948.25.9) (Fig. 5). The placement of the deceased's name away from public view and next to the skin of the wearer indicates that the emphasis was placed upon the more private, sentimental act of remembering. Similarly, it suggests that even when a woman could not afford to purchase a large piece of jewellery or pay for the engraving of a lengthy memorial, or when it was simply impossible to do so due to the delicate nature of the article, they longed for a record of their loss.

27 However, other pieces of jewellery possess a fair amount of historical detail and biographical information about the deceased, which seems to indicate that their legacy as a communicative family heirloom was recognized. One particularly striking object in the ROM's collection is an English mourning bracelet dating from 1851-1852 (ace no. 970.41.3) (Fig. 6). The textual inscription is quite lengthy and rims around the inside of the bracelet as well as appearing on the back of the pendant hanging from the piece's central decoration, a St Andrew's cross.33 Together, the text reads: "In memory of Henry Barras who (with his brother George) died of fever at Milan August 24th 1851 Aged 31 'In death they were not divided'" and "In Memory of George Barras who died at Milan Augt 24 1851 Aged 23."

28 Samplers in particular were a historical text that predated women's widespread involvement in historical writing. All of the samplers considered within the context of this paper were written during the period 1817 to 1849. As demonstrated by the genealogical table dedicated to the Wolstencrofts family by Ann Wolstencrofts in 1849, samplers offered the possibility of immortalizing an ordinary family and asserted the role of women as the memory banks of the domestic sphere (ace. no. 954.111) (Fig. 1). In addition to depicting the family home, the Wolstencrofts sampler lists the birth dates of Charles and Betty Wolstencrofts as well as the birth dates of their children — and their deaths where applicable. These mourning objects provided a voice, a form of representation, for those people who were silenced or misrepresented in traditional histories. Indeed, they reveal the humanity behind the names that appear in the barren public records of birth and marriage certificates. At the same time, they demonstrate the emotional and physical investment of the women who generated and maintained an accessible, sentimental, and beautiful testament of the people that they loved and cared for throughout their fives, safeguarding their memories after death.

29 Finally, the distinction, in both imagery and text, between remembrances of men and women needs to be considered in order to understand mourning objects as a particularly feminine form of commemoration. As an analysis of the ROM's collection demonstrates, there were gendered differences in the way that women commemorated their loved ones. In this way, these objects reflected conventional expectations of men's and women's status, sex roles and gender relations while at the same time, the act of commemoration was a subtle challenge to and subversion of the traditional male hegemony over the historical narrative. The way a person is represented by a mourning object is often an idealized vision, a type of wish fulfillment and reinterpretation engaged in by a grieving woman. And, after all, "whatever the complexity and ambivalence of a woman's personal response to bereavement, embroidering conventional mourning pictures provided the security of social approval."34

30 An examination of two pieces of mourning jewellery, a brooch dedicated to the memory of a man and a bracelet that pays tribute to a woman, reveals the manner in which idealized gender roles and relations, the perception of separate spheres for men and women, affected the form and content of mourning. The "masculine" brooch is believed to be English in origin and dates from approximately 1850 to 1865 (ace. no. 977x39.10) (Fig. 7). It is a rather large, heavy and ornate gold brooch with a round shape and swivel design. While the "front" of the brooch features a portrait of a gentleman, the reverse side boasts an extravagantly, yet delicately, prepared spray of hair with four small pearls at its base; a number of smaller pieces of hair are lavishly strewn around the main fan of hair, like rose petals at the feet of a prince.

31 The gentleman depicted is middle-aged and well-dressed, with a proud, self-assured and content look on his face; he appears robust and his wealth, or aspirations to status, are indicated by a large pinky ring and gold watch chain, which are prominently featured in the photograph. The brooch appears to be a sign of the high esteem, and perhaps even love, with which the gentleman was held; it is almost like a campaign button in that it "advertises" the importance of the man, whether a husband or father. If his wife or daughter prepared this hair-work personally, it indicates that they were wealthy enough to have a great deal of leisure time as well as training in the proper accomplishments of "ladies." It is a very substantial and impressive piece, befitting a man comfortable with assuming a leadership role in the community through his involvement in voluntary organizations or the demanding worlds of government, business, and the professions. As depicted in the brooch, the man embodies the Victorian ideal of masculinity. By rigorously adhering to middle-class definitions of proper conduct, dress, etiquette, speech, and emotional control, the public man demonstrated his allegiance to the values of "industry, thrift, rational behaviour, and above all, self-discipline."35 Surely, given appearances, he must also be a good husband and father.

Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 732 This "masculine" brooch contrasts quite markedly with a rather "feminine" mourning bracelet found in the ROM's collection. This particular piece is English in origin and dates from somewhere between 1844 and 1846, the height of the cult of domesticity (ace. no. 945.24.44) (Fig. 8). It is composed of brown hair that has been braided quite simply to form a rather wide band, joined together by a clasp that features a large oval picture frame containing a lady's picture. The woman appears very "motherly." As well as being middle-aged and dressed in her Sunday best, she possesses a kind face with the hint of a smile about her lips — all of which renders her very suitable to baking cookies. One can imagine her being completely devoted to the happiness and well-being of her family. It is a simple yet elegant piece, but the most interesting aspect of its style is that the hair is in direct contact with the arm of the wearer. It is almost like a shackle of hair. As a result, il hints at a great deal of intimacy in the relationship between the mourner and the deceased. Given the idealization of the mother-daughter bond during the period, one can imagine a daughter wearing it in order to feel close to, and derive comfort from, the memory of her mother with whom she had a very strong relationship based upon love, friendship, and mutual confidence.

33 Similarly, there are two samplers that provide insights into the differing commemorations of men and women. The poem entitled "Sacred," composed by Isabella Torrance in tribute to her father, James Torrance, a Kingston merchant who died on September 10, 1817, expresses her desire to preserve her father's name for eternity through her embroidery work (ace. no. 970.184.2). Within these lines, Torrance remarks that she seeks "To consecrate to humble fame/A dying father's honoured name." She thereby claims a place for him in both her personal and the larger historical memory. Yet, as in the feminine biographies of the period, his importance stems from his role as a father. The sampler's text and spare design, with its very simple black stitching set against a completely unadorned white background, reveals that, despite the sense of awe and respect that was supposed to bind relations between fathers and their children, there was also the possibility for love and many children experienced a devastating grief upon their fathers' death. The plain, "manly" sampler crafted in honour of James Torrance is both powerful and poignant as it was the only opportunity his daughter would have had to express his meaning to her; it was the forum within which she could express her feelings following her father's death. This sampler was her memorial to him, constructed apart from the obituaries that were found in the male-dominated medium of the newspaper.

34 Yet, Isabella's loving tribute to her father is very different from the sampler embroidered in remembrance of Amelia Perry Bagwell, who died at Lockport St, New York, on June 12, 1842 and who was paid respect by her schoolteacher H. G. (ace. no. 974.393) (Fig. 2). This colourful sampler integrates a number of well-known domestic symbols, representing femininity and death, into its design. There is an elaborate floral border as well as an image of a church and a coffin flanked by a weeping willow, a patch of grass and a fence. With its detailed embroidery, as well as the lengthy poem it contains, the creation of this sampler would have been a very time consuming endeavor. As a result, it demonstrates the worth that H. G. accorded her former pupil. The verse written in commemoration of this young girl laments her too early death, her "life so brief," while tempering this sense of earthly suffering and loss by inspiring hope and faith in the promise of a better life to come in the "heavenly kingdom." It claims, "[m]ourn for the mourners but not for the dead" who enjoy "death's calm and holy sleep" beyond "this cheerless earth." The poem is very sentimental, evoking memories of "Little Eva" from Harriet Beecher Stowe's novel Uncle Tom's Cabin, with the youthful innocence and feminine identity of the deceased emphasized throughout. Yet, it is a more uplifting and comforting reminiscence than the one for Isabella Torrance's father, which stresses her "mournful" "throbbing heart." Perhaps this is rooted in the dependence of children, particularly females, upon their fathers for status and security. He exercised control over their life's possibilities; without him, the future was precarious indeed.

The Shifting Value of Mourning Rituals and Objects in Women's Lives

35 The de-emphasis upon the rites of mourning as a pertinent site of memory during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries corresponded with the increasing role played by women in the preservation and communication of a larger historical narrative through their efforts as teachers and museum workers. During this period, marked by increasing urbanization, industrialization, and immigration, there arose a novel development in women's engagement in historical commemoration, who and how they remembered. The historical orientation of value during the period was an extension and validation of their symbolic guise as the mothers of civilization, the guiding force for social, cultural, and moral uplift. Women's role in crafting and disseminating a vision of the past extended beyond the story of the home and family, moving onto a more grand and public scale instead. Indeed, the story of women and the family was often forgotten as it was subsumed under the patriotic tale of national development. Women's new commemorative task was intertwined with their traditional role as "mothers," except now they would identify with and help the national self. Through their historical efforts, women would guide and shape the values and behaviour of the society as a whole.

36 In the late nineteenth century, women's historically-minded activity partly revolved around their work as teachers and their involvement in the historic house movement. Within the classroom, women inculcated the nation's children into citizenship by reinforcing their society's dearly-held values, attitudes, and beliefs through their presentation of the past. At the same time, much of women's commemorative work as teachers and within the historic house movement was more conservative and conventional than the narratives that they had constructed through the act of mourning.

37 Through their pioneering efforts in the historic house movement, middle- and upper-middle-class women claimed a place in the public realm of historical commemoration, thereby expanding traditional definitions of women's activities, at the same time that they relayed traditional domestic platitudes and outwardly represented the feminine ideal. Historic house museums were largely the preserve of voluntary women's organizations. They were headed by socially prominent, wealthy, and charismatic women who established these sacred sites in the hopes of asserting their political ideology and realizing their social vision. Southern matron Ann Pamela Cunningham founded the Mount Vernon Ladies Association in 1859 in order to prevent the former home of George Washington from being turned into a hotel. She hoped that a physical reminder of America's founding father would serve as an inspiring and unifying force in a nation looming on the brink of civil war.36 Canadian Sara Calder, who led the Women's Wentworth Historical Society (WWHS) to their triumph in saving the old Gage Homestead and erecting a monument at Stoney Creek Battlefield, was similarly motivated by strident patriotism as well as imperialist feelings. By the turn of the twentieth century, it was considered "proper for upper-class women to preserve and present history to the public."37 However, in order to realize their duty as saviours of historic homes, women engaged in massive fundraising efforts and publicity campaigns, demanding a measure of fame and esteem for their contribution to preserving the nation's historical memory.

38 Despite being female-driven, the format of historic homes largely adhered to the "great man" philosophy, commemorating "almost exclusively wealthy, white, male political, entrepreneurial, or military figures."38 Their primary departure from the norm was their linkage of these men's success to the influence of the domestic environment and, in particular, women's special maternal qualities and gentle guidance. As the bourgeois home was conceived of as the source of a cohesive, homogenized national identity, which would compel future achievement, the homes selected for sanctification were viewed as iconic models of domesticity. By carefully adhering to the lessons about appropriate values and behaviour contained within this idealized past, a seemingly fragile — yet inviolable — way of life would be preserved.39 As a result, the homes contained a heady mix of nostalgia and pedagogy with the visitor expected to assume the stance of a humble pilgrim seeking instruction and rebirth.

39 The practice of mourning was therefore rendered less important as an historical indulgence, than this public ritualization of the national past. Traditional mourning customs detracted from women's abilities to dedicate themselves to saving a disappearing national past or realizing other patriotic and imperialist objectives. The excessive grief and ostentatious and unpractical dress of mourning, as well as the accompanying withdrawal of women from public life, was out of step with the altered position of these "new" women.

40 As Mary Ryan suggests, towards the end of the nineteenth century, middle- and upper-middle-class women were growing increasingly comfortable with moving across the public landscape of the city, whether they were social reformers, shoppers, or simply seeking other forms of female-friendly recreation. These women were transforming the very nature of public space through their "sanitizing" presence. Urban planners conceived of and built safe places where "endangered" "respectable" women could claim a public space. This included the new public parks, libraries, skating rinks, ice cream parlours, theatres that showed matinees aimed at "ladies," and especially the department stores that included ladies' parlours and lunch-rooms.40 These busy women resented the expense of the full regalia of mourning attire, and were unwilling to remain sequestered for a long period of time. Indeed, Queen Victoria engendered a fair amount of displeasure, and even outright hostility, when she neglected her public duties following the death of the Prince Consort. This nascent critique eventually led to a well-organized reform movement that contributed to the demise of elaborate mourning practice.

41 The modest and economical mourning dress of the Edwardians reflects this desire to simplify the practice in keeping with women's more active social role. The ROM's collection includes a black and brownish-green silk lady's mourning evening dress and accompanying wide belt (ace. no. 942.27.19.A and B). With its intricate designs and pretty floral pattern, its black net overlay and high boned white net collar, this 1914 gown is interesting for its sheer ordinariness. It is remarkable in that it is barely distinguishable as a mourning gown, only the dark colour indicates its purpose. With its straight, nearly floor-length skirt, the dress reflects the fashion of the times; indeed, it seems more concerned with being functional and stylish than with communicating self-negating grief. It would appear that the wearer donned this gown out of custom and a desire to obey the rules of etiquette. As well as reflecting the relaxation of the rules of mourning dress, this gown defines the outfit of a woman who, even if she recently lost a loved one, has a lot to do. Similarly, the jewellery explored during the preparation of this paper dates prior to or just around the turn of the twentieth century. According to mourning jewellery collector Margaret Hunter, it is extremely rare to find any pieces of jewellery dating from the period after the early years of the twentieth century.41 This indicates women's increasing preoccupation with other subjects and forms of historical memory.

42 Yet, as the Royal Ontario Museum's collection of mourning dress and accessories indicates, even once these objects were no longer the prominent tool in women's efforts at shaping the popular historical imagination, many of the remnants of mourning rituals were kept and passed down within families as treasured heirlooms before being transferred to the ROM. By assuming the "authoritative" status of a cultural memory bank, by taking responsibility for care-taking and myth-making from the objects' female owners, the ROM preserves and communicates the family stories that were lovingly recorded and safeguarded by generations of women. In transferring their items to me ROM, many women may have sought to achieve a final synthesis between their families' pasts and the national historical narrative, celebrating their unique saga in a public space. However, the reality is more complex, as these women were also surrendering control over their stories to a male-dominated bureaucratic institution.

43 An examination of the ROM's catalogue records reveals information about the identity of the donors, perhaps hinting at their motivations for surrendering these cherished items to a prominent museum. The questions that need to be considered are who donated these artifacts?, what did they donate?, and why? Or as Alon Confino queries: "who wants whom to remember what, and why?"42 Of the thirteen objects of primary consideration in this paper, of those which were not given to the ROM by unknown donors or by a trust, all of them were donated by women; one object was a joint donation by a woman and a man. Many of the same names reappear throughout the catalogue records as donors of sundry items. It is also interesting to note that of the ten donors whose names are known, six are identified as "Miss" while three are designated as "Mrs," and the remaining donor does not receive any such tide. Of these items, where the source is known, only one was a purchase — the mourning brooch that features the image of a lily and a forget-me-not as well as the phrase "Cut Down like a Flower" (ace. no. 958.134.1) (Fig. 4). The rest of the objects were gifts to the ROM.

44 A consideration of the sex of the donor, as well as whether it was a gift or purchase, in conjunction with the entire collection of thirty-four objects leads to the following findings. Where the donor is known and it is not a library or trust, it is most commonly a woman, who is likely to be unmarried, and it is a gift, often from her estate. For example, one catalogue entry, in describing the provenance of a Canadian mourning hat and veil from the period 1832 to 1840, explains that it belonged to the grandmother of a woman who, upon her death, bequeathed it to the female executor of her estate, who in turn donated it to the ROM (ace. no. 977.165.15).

45 Most catalogue records do not contain any additional information about the artifact's family of origin, but a few of them do. When these notes are provided, they are a welcome source of insight into the history of the items and the possible meanings they held for their owner. These notes emphasize the connection between different generations of women in the same family. For example, one brooch, which contains a woman's picture on the front and a braided lock of her hair on the back, is credited as having been made in honour of the donor's great, great grandmother (ace. no. 990.61.9). Another artifact, a Canadian mourning bonnet from 1878 to 1905, is accompanied by a more detailed account: "The Hollinrake family came to Canada from England in the 1830s and settled in Dundas, Ontario" (ace. no. 994.160.1). These brief lines evoke a feeling of pride and satisfaction in the story of an immigrant family, while orienting the contemporary viewer of the object to the original owner's place in time and space. Finally, the aforementioned sampler that depicts the lavishly decorated genealogical table of the Wolstencrofts family is explained wim the note: "Belonged to Charles and Betty Wolstencrofts, who were United Empire Loyalists and settled in York County. Former home depicted." (ace. no. 954.111) (Fig. 1). Together, these findings lead to a number of conclusions.

46 Traditionally, women have assumed the position of family historian, maintaining a continuous and meaningful sense of identity for themselves and the larger unit in the process. Even with monumental changes in women's roles and status, their identity remained integrally tied to their family. With the passing of a mourning object from the original owner down through the various female representatives of the family, the memories embodied within and expressed by these objects inevitably changed. From the original desire to remember a specific loved one, to consign their name or image or even a part of their physical being (hair) to historical memory, the objects were, through the act of giving to the next generation, transformed into a feminized family legacy. In the passage from mother to daughter, or aunt to niece, a sampler or brooch became a symbol of the family, of one's roots, and in this way it assisted the receiver in understanding and defining the self. More importantly, these mourning objects represented a woman telling her story, and that of the people who shaped and gave meaning to her world, in her own unique voice. At the same time, the female descendant's sense of connection with the person being remembered is less important than his or her representational value as a symbolic figure, as a sign that the inheritor is part of, and in their own way is contributing to, a narrative that is larger than the individual self. Hence, while it is only supposed that it is the woman's great, great grandmother who is portrayed in the brooch, the piece retains its power to connote a valuable personal and familial identity that transcends temporal restraints.

The Role and Responsibilities of the ROM

47 Given the implications of this line of thinking, I would argue that the ROM only comes into play as a receptacle for these items when they have nowhere else to go. These objects enter the more sterile domain of the museum when the female donors are the end of the family line, perhaps because they never married or because they failed to produce female children. Seeking to protect their piece of a unique part of the nation's social and women's history, and indeed, hoping to save the emotionally powerful objects that form an essential component of the self, they either give their "antiques" to the ROM or bequeath them to a close female friend or more distant relative who they feel will cherish an object that contains the key to their collective memory. By donating these "keepsakes" to the ROM, women hope to ensure the immortality of their family's name, thereby ensuring that their contribution to the development of Canada, its physical, cultural, and social landscape, is recognized. In the process, they interweave the story of their family with the larger historical narrative that is represented within the ROM. As a result, the women who created or wore the objects, the people who are commemorated, and the donors themselves are integrated into the national myth.

48 However, in bequeathing their heirlooms to the ROM, these women relinquished their personal, feminine control over these objects. During the early twentieth century, many of the gains achieved by women in the realm of historical commemoration were lost due to the increasingly narrow and male-dominated historical domain. Beginning in the 1880s, there was a self-conscious attempt to professionalize the discipline historians studied and taught with history conceived of as a scientific discipline requiring specialized framing and a uniform, objective approach. By the 1920s, the definition of history as the experiences of elite men and of "high" politics was finalized. As a result, the distinction between university-trained men and female amateurs or "dabblers," including those women active in historical societies and the historic house movement, was formalized.43 With their emphasis on the "smaller matters of human experience," much of women's historical work was located outside the work of male scholars, and even denigrated by male amateurs, for its supposed lack of rigour as well as its triviality, sentimentality, and moralizing.44

49 Similarly, by the 1920s and 1930s male parties began wresting control of the historic house movement away from voluntary women's organizations. In the United States, private business interests led the way — a group of New York lawyers and financiers saved Monticello while wealthy industrialist John D. Rockefeller Jr established his paean to the founding lathers, Colonial Williamsburg. The federal government entered the realm of the preservation and interpretation of historic sites in the 1930s, with the National Parks Service assuming a professional supervisory role.45 With the establishment of the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada in 1919, the federal government assumed responsibility for acquiring, "imagineering," and operating officially sanctioned national historic parks and sites. In the process, a male-dominated bureaucracy took over from community-driven initiatives that were more sensitive to input from locally prominent women.46

50 Finally, the presence of mourning artifacts reveals a great deal about the legacy and responsibility of the ROM in terms of the construction and maintenance of memory. In essence, the question we must ask is, what does the ROM's collection of mourning artifacts mean to the visitor who encounters them during an exhibition, such as the 1995 show "From Corsets to Calling Cards." In discussing the rise of museums, collections, and exhibitions during the nineteenth century, Liliane Weissberg comments that "objects...became the means of regaining a cognizance of the past and promised a means to hold onto it."47 Within the ROM, these objects become a tangible method of accessing and understanding the past. In the process, they shape the way that modern audiences construct and experience the past; they affect the way in which museums and modern visitors conceptualize terms like "Victorian." The middle-class sentimental feminine perspective contained within these objects becomes accepted and disseminated as the embodiment of Victorian values, beliefs, and behaviour.

51 These artifacts that reflected women's efforts to remember, to historicize, their loved ones through their homes, their craft work, and themselves, shape and become part of Canada's "shared cultural knowledge."48 The tired and worn face of a woman in a brooch, the carefully arranged spray of hair bound with pearls, the lovely jet brooch with floral motifs, all serve as reminders of the hardships and accomplishments, the lives of love and loss, and the many other experiences and responsibilities of real women and their families. As mentioned earlier, there is a raw humanity, an immediacy and poignancy, to these objects that is inaccessible in other text based records of history. To neglect them would do a great disservice to these women and to the larger story of Canadian history as they provide a key to understanding the most essential aspects of the past.

Conclusion

52 Therefore, the ROM's collection of mourning objects provides a prism through which to glimpse and grapple with the efforts of middle- and upper-middle-class Victorian women to establish and disseminate a meaningful feminine identity and historical memory. At the same time, this type of study provides insights into the role and responsibilities of the ROM in terms of creating and perpetuating a certain vision of the past. For middle-class Victorian women who were largely excluded from formal, public commemorative efforts and male-dominated historical practice, mourning formed an "invented tradition" through which they defined and realized their own accessible experience and articulation of a domestic and feminine historical memory.

53 This form of "remembering" was centered upon the intimate, personal past of their family and friends, the ordinary people, men and women, who were neglected by traditional histories, and revolved around the sites of memory that they did possess control over, their homes and bodies. Through the appropriately feminine and eminently respectable practice of "mourning," women were able to claim an ever widening role in the construction and content of public history and commemoration, asserting their power to be seen and heard in the public sphere. They outwardly embodied the "cult of true womanhood" while also questioning and challenging the validity of its dictates. At the same time, an examination of the shifting importance of mourning as a means of generating and transmitting histories reveals the manner in which the changing expectations and assumptions about the social role of women affected the meaning and status of mourning as a feminine ritual that allowed for the validation and transfer of women's traditional skills, knowledge, and sense of self. All of this indicates that a little black bordered handkerchief is far more than it seems.

I would like to thank Shannon Elliot, Adrienne Hood, Anu Liivandi and Cecilia Morgan for their help during the preparation of this paper.