Articles

Life and Work in the Brigus Knitting Mills, 1953-1970

Abstract

This paper looks at the operations and products of the Eckhardt Mills (named the Brigus Knitting Mills in 1959) in the Post-Confederate context of Newfoundland between 1953 and 1970. It looks at the design and production problems, the crafted products being produced, and the reception of them by women in the Newfoundland and mainland Irene Stores. The information has come from informants who were connected to the Mills, women who were buying the clothes, from the business records and financial reports of the company, and from the research of Newfoundland academics interested in the period. The Irene knits are reminders of what many believe to be the failed dreams of "Joey" Smallwood, Premier of Newfoundland in the post-Confederate period, but for others they are symbols of a period of positive and productive energy in the province's history.

Résumé

Cet article se penche sur l'exploitation et la production des usines de bonneterie Eckhardt Mills (deven ues les Brigus Knitting Mills en 1959) de 1953 à 1970, peu après l'entrée de Terre-Neuve dans la confédération canadienne. Il s'intéresse aux problèmes de design et de production, aux tricots fabriqués et à l'accueil que les femmes réservaient à ces produits dans lesmagasins Irene situés à Terre-Neuve et dans la partie continentale du Canada. L'information à la source de cet article provient de témoignages de personnes associées aux usines et d'acheteuses des produits, de dossiers commerciaux et de rapports financiers de l'entreprise, ainsi que de recherches universitaires de Terre-Neuviens portant sur la période. Pour plusieurs, les tricots Irene sont un rappel de ce qu 'ils considèrent comme les rêves infructueux de « Jœy » Smallwood, premier ministre de Terre-Neuve à l'époque suivant l'entrée dans la confédération, mais pour d'autres, ils sont les symboles d'une période riche en énergie positive et productive dans l'histoire de la province.

1 During the period 1900 to 1940 Newfoundlanders had quite a ride: troubles in the fishery were compounded by war, the Depression and, in 1934, the loss of responsible government to a six-man commission who took charge of government affairs. Two events that helped turn this around were the arrival of the American military in 1942, and Confederation with Canada and Joey Smallwood's premiership in 1949.

2 The American presence in Newfoundland during the Second World War and the Cold War that followed was huge. Several military bases were built (St John's, Argentia, Stephenville and Goose Bay) bringing full-scale employment to thousands of men and women from outport communities. The American bases became the centres of not only work but also of much of the social activity (estimates are that 20 000 to 40 000 Newfoundland women married American GIs through this period1) and women in Newfoundland as elsewhere went through quite a change — if once plain and unadorned, they were now dressing for a new Americanized style of life.

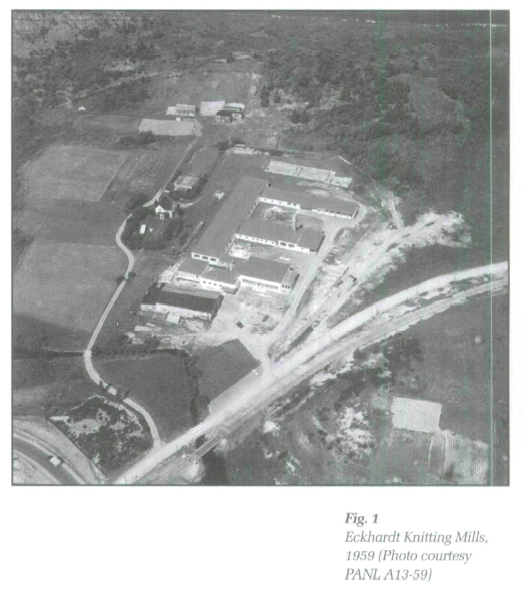

3 But by the end of the 1940s (and after fifteen years of commission of government) many Newfoundlanders were still lagging "behind [mainland standards] in terms of creature comforts such as furnace-heated homes, hot and cold water, flush toilets, baths or showers and telephones,"2 and many were pulling up stakes and leaving. To stem the tide Smallwood, in 1952, promised the creation of an "Industrial Program" that would bring 15 000 new jobs3 to out-of-work Newfoundlanders. In a six-week tour of war ravaged Europe, Smallwood sought out industrialists willing to set up manufacturing operations in his new province. He and his Latvian Director General of Economic Development, Dr Alfred Valdmanis, met with Austrian knitwear manufacturer Alphonse Eckhardt, who was soon given the go-ahead to set up a knitting mills factory in the outport community of Brigus, Conception Bay.

4 In 1953 construction began, followed by the arrival of forty-two flat-bed (automatic and mechanical) knitting machines and a core of Austrian women brought in to train the Newfoundland employees. They were, by 1955, starting the production of some one-hundred different designs of high-end knitwear products that were sold in company-owned "Irene Knitwear" outlets in St John's, Montreal, and Toronto.4 Joey's new "Industrial Program" saw the opening of fifteen additional factories producing everything from gypsum to rubber boots. Headlines of the period read: "Nfld Workers are Going Money Mad" and "prosperity is going to people's heads"..."they are not keeping their feet on the ground."5 The optimism was great. When in 1953 Sears moved into the new province, there were expectations that "...the company would take a very large percentage of the total production of the plants."6 But Joey's industrial efforts quickly began to go astray; by fall of 1955 Valdmanis was jailed for embezzlement, and many of the new factories were facing financial crisis.

5 The shores of Conception Bay North became the centre of clothing production: the Newfoundland Leather Tannery, Koch Shoes, Atlantic Gloves, Gold Sail Leather Goods, and the Eckhardt Knitting Mills. These production-line operations employed many hundreds of men and women from the surrounding Conception Bay communities.

6 At the outset there were promising forecasts for the Eckhardt Mills. A 1953 study of the knit goods industry in Canada7 showed the bulk of ladies knitwear produced still being made from wool (a trademark of the Mills); and the man-made synthetics, that were to become the trend, represented a relatively small volume of the trade at this time.8 The market was shared with only one other company producing knitwear in Canada so it would seem that the Brigus woolen goods operation was well timed to enter the scene.

7 This was a period that saw a revolt against the mean and conservative wartime styles. Knitted materials were ideal for the figure-enhancing shapes being worn; sweaters, dresses, pants and cardigan-jacket suits were all the rage and coordinating these with gloves, bags and shoes was an important consideration. The high-quality sportswear fashions, coming from the Brigus Mills, had great appeal and women at all levels of Newfoundland society began wearing the Irene knits. Anne Kieley Ryan, a Brigus Knitwear enthusiast, says of the period in the province that "you were nobody if you didn't have an Irene knit!"9

The Eckhardt Mill: Work and Workers

8 The Mills were modelled after Eckhardt's operations in Austria. He designed the building in his name in the shape of a capital E (Fig. 1). It was very modern in scale and concept, designed with bright, clean and efficient working spaces. The main production area was enormous (seventy five metres in length) with big sunny windows all along one side. There were integrated living quarters with rooms, apartments and executive suites for the Austrian staff, a kitchen and dining area in the central wing, a recreation centre, volleyball and badminton courts, and a dance hall with a balcony for an orchestra.10 Eckhardt was optimistic about the possibilities saying:

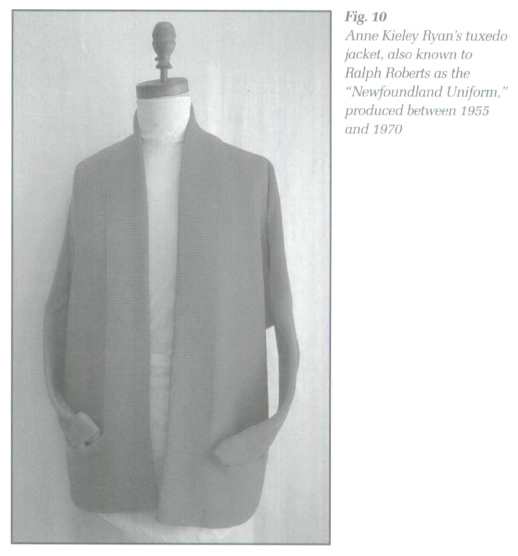

Mary-Catherine Burke of Brigus was fifteen in 1953 when she first met the Austrian construction workers. She and her friends would hide and throw snowballs, and pass by the men in groups when they walked through the town. Many, like her husband-to-be Fred Heistinger, had come over as part of the construction team and were living in the "bungalow" in Brigus. She laughs recalling how:

Nevertheless it did not take long for the people of Brigus to accept the newcomers as part of the community even "the nuns who had warned [them] not to mix with the men."13

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2 Display large image of Figure 3

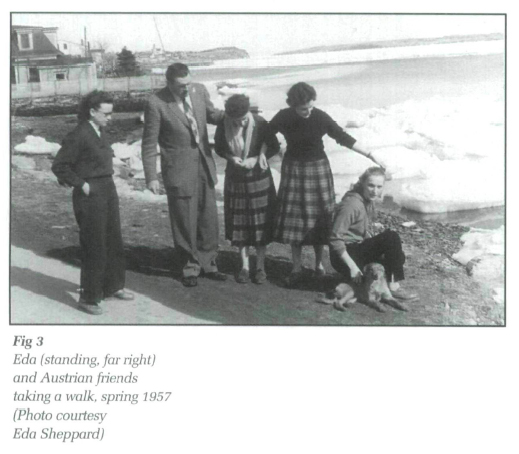

Display large image of Figure 39 When in 1955 the Austrian supervisory staff arrived to live and work at the Mills they were to become isolated from the community in some ways, as the Mills sit alone on the outskirts of town (Fig. 2). Eda Koefler was a supervisor in the sewing department and she remembers those days:

It was in the kitchen at the Mills that jig's dinner and goulash were meeting for the first time! (Account manager Ralph Roberts15 remembers the food: the goulash, the pasta and the rice; he had not seen this eaten before.) Eda had left her home in Upper Austria where she worked as a hand and mechanical knitter in a weaving factory. She had left a country, she says,16 whose "infrastructure was in tatters, there was nothing, no government, schools, everything closed but some private business and factories were still okay." Her first impressions of Newfoundland were of the colourful houses and cars in contrast to her home with its grey buildings of mortar and dark stone.

10 It was in Brigus that Eda met her new friend Maigrit Sevfert from Vienna and they soon moved from rented rooms into their own apartment at the Mills (they got their citizenship together and met Joey on this occasion). In her second year in Brigus, Eda was invited by one of the knitters to her first Newfoundland Christmas dinner. She was dating her new beau Harry Sheppard by then (1957) and they celebrated New Year's at a dinner and dance at the "Woodstock" in Holyrood that year.

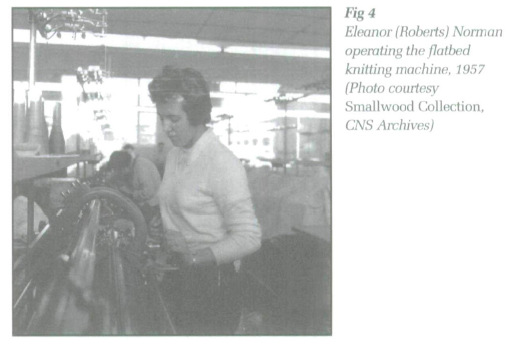

11 Eleanor (Roberts) Norman (Fig. 4) was from Brigus too, and started working at the Mills in 1955. She had good relations with the Austrian supervisory and training staff, Eda was her boss. Eleanor was one of the first to learn how to operate the automatic flat-bed machines and she was delighted with the products she made saying:

Eleanor's work included the creation of the early "fully-fashioned" designs. These were products that required a separate loom to create each piece of the goods (sleeve, cuff, facings, collars, etc.) and which came off the loom as completely finished pieces, which were carefully sewn with a near seamless technique. These finishing details were what the high-end consumer wanted in her clothes; the mark of quality seen on the inside as well as the outside of the garment.

12 By the summer of 1957 there were 89 employees including 8 Austrian supervisors, 27 knitting workers, and 46 women in pressing and sewing operations at the Mills; female employees worked for fifty cents hourly and males at sixty — these rates were roughly half those of a comparable knitting mill operation in Montreal at $1.20 per hour.18 Supervisory positions were on a par with professional salaries paid to Newfoundland government employees at that time at $350 a month.19 Ralph Roberts (account manager at the Mills), says that "work began at 7:30 a.m. and it was produce, produce, produce. There was a half-hour lunch, two fifteen minute breaks and quitting time was at 4:30 p.m."20

Problems at the Mills

13 When Ralph Roberts was hired in the fall of 1956 he was given instructions by Gordon Pushie (the new Director of Economic Development) "not to take orders from anyone from the other side of the Atlantic."21 Roberts says that "Eckhardt had disappeared and the plant had been at a standstill since May;" The Austrian entrepreneur had parted company with the Mills the previous year, and he was not a happy man. In a letter to Pushie22 he speaks of the government's "refusal to authorize payment of outstanding amounts" [$16 672] and was concerned about the "possibility of a sudden refusal to extend [his] residence permit." Eckhardt explains:

The Mills' staff was managing without Eckhardt's direction, but there were many problems beginning to arise. In his 1957 study of the operations, Arthur Little of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, recommended that the Mills "must obtain new, capable, and aggressive management."23 Little felt that a major reorganization of the company was required, and if this was done there was a chance that the Mills could see a profit within a year.

Display large image of Figure 4

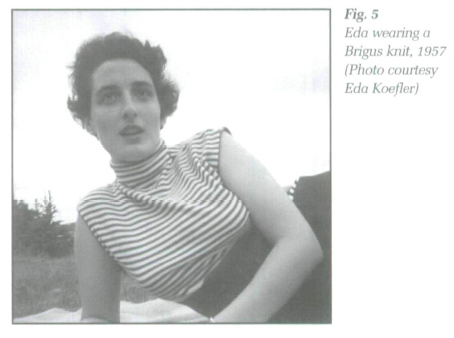

Display large image of Figure 414 An obvious problem was the production of the over one-hundred different designs at the Mills at this time. Of those produced, in quantities of over one-hundred in 1957, there were two jacket styles, three cardigans, one slacks, two skirts, eleven pullovers (Fig. 5) and a bolero style. Between January and June records show24 over 8 000 in all being produced. But this was a fraction of the capability of the plant; many of the machines were lying idle and there was a build-up of inventories that were not being sold. Meanwhile the manager of the St John's Irene Store was complaining of a lack of inventory in the popular colours that customers desired.25

15 The style that was never in doubt was the Tuxedo Jacket. It was the bestseller and represented over thirty percent of 1957 sales. It "swept the province" says Ralph Roberts and became what he called the "Newfoundland Uniform."26 Retailing at $25.30,27 it was one of the original fully-fashioned items with its well-tailored finishing that was desired by the high-end consumer (who wanted quality on the inside of her garment as well as on the outside). The tuxedo had a thick, ribbed finish and was originally made from the fine Austrian merino wool;28 it was warm and ultimately practical for Newfoundland wear.

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 616 Arthur Little felt that "greater company sales on the mainland [were] possible" at this time saying that "fashion woolen knitted goods are currently in great demand,"29 but lack of new designs was a real problem and it needed to be solved. In his report, Little goes on to say that "the high quality fashion items suffer from static outdated designs...There has been no change in the style of its line since it was introduced in 1955."30 Mainland buyers' comments include such phrases as: "too Germanic...Very Teutonic...old-hat English...too complicated;"31 adding that the colours, the sizing and the pricing were inconsistent.

17 The company needed a topnotch designer; failing that, Little recommended copying the European imports from American high-fashion specialty shops such as Bergdorf Goodman, Bonwit Teller, and Lord and Taylor in New York.

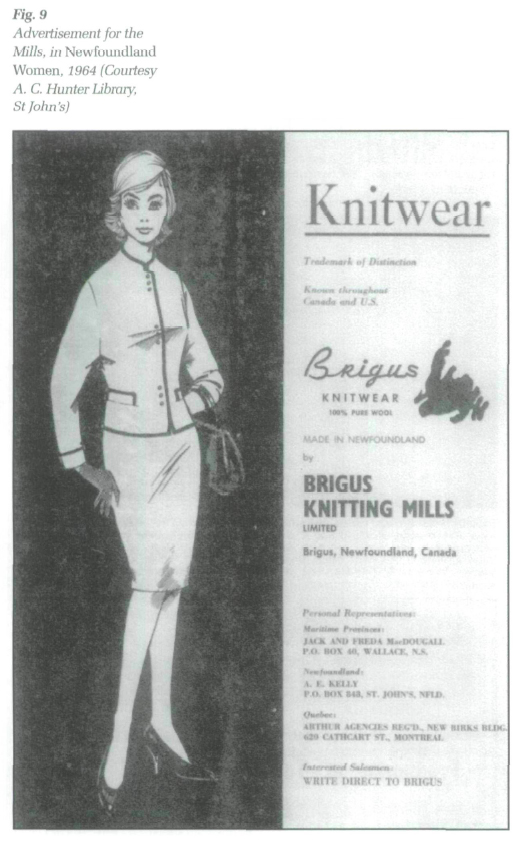

Several employees had been "trying their hands" at design during this time. Supervisor Margrit Sevfert from Vienna was doing this work in the early years, "but Margrit," says Eda Sheppard of her old friend, "wasn't really a designer; she learned as she went along."33 In 1957, Ted Bodin, with the Iron Corporation of New York, put together a line of samples that was shown to American buyers, but correspondence shows there was no follow through from his work.34 In the late 1950s it was Mary-Jane Bartlett from Brigus who took over designing the line. This had always been Ralph Robert's wish: "to see more of the Brigus people rising in the work at the Mills."35 Ralph was taking on some of the design duties him self at this stage. He created two of the four labels the company used throughout his fifteen years with the Mills: Styled by Brigus and Brigus Knitwear (Fig. 6).

18 In response to the Little Report, Toronto consultant Fred Werker was hired in 1957, and it appears that his work brought improvement in sales; by 1959 they were up some twenty-five percent from the previous year: in St John's at $156 000, Montreal at $18 000 and Toronto at $61 000.36 Werker brought in a round-the-clock, six-day-week shift system for the busy times of the year, and instituted a piece rate production method to help encourage employee output at the Mills.37 The original fully-fashioned items were now replaced with "cut" goods made by assembling the pattern pieces (cut using automatic cutting tools and paper patterns) from woven goods "after" they came off the loom.38 Many of the yard-goods were now being imported and some of these were in wool and synthetic blends — Anne Kieley's dress (Fig. 7) is a good example of this change.

19 Changes, sought during the Werker period, include improvements to the Canadian mainland Irene stores: renovations to the structures, new showcases and dressing rooms; improved marketing and display where Little had found "inventory several years old and shop-worn"39 goods. Werker organized promotional photos of employees performing their work at the Mills (Fig. 4).40 But in 1960 Werker was let go. His ten-day, one-thousand dollar, monthly contract (plus travel back and forth to Toronto and Montreal) was far too expensive; it was a "luxury" the government could not afford.41

The Newfoundland Fashion Scene

20 The troubles at the factory and the lack of enthusiasm of mainland buyers were of little concern to the women who were buying the clothes at home. The early Irene Knitwear attracted resounding applause. Much of the goods had been imported by Eckhardt from his Austrian plant;42 it was excellent quality; it was expensive and viewed as a status symbol for many women in the province at the time.

21 Anne Kieley Ryan of St John's was a very big fan. At sixteen she started work with the federal unemployment office, in St John's, and got used to the independence and the good money she earned. Anne says she "would pay a half month's salary for a dress and maybe $75 for a pair of shoes and everything had to be matching!"43 She shopped on Water Street in all the big department stores — The Model Shop, The London, Wilanskys, Swerskys, Bowrings and Ayres — where she found her favourite designer labels. When Anne went into nursing in 1957, at age twenty-two, she took with her a trunk and three suitcases of clothes including her favourite designer labels, her Jonathan Logan, Gorray, and Nat Gordon designs as well as her many pieces of Irene Knitwear. That year Anne bought her red "tuxedo jacket" and all the girls in nursing school "had a turn with it."44 In 1961, after Anne was married, she wore her favourite red Irene Knitwear dress (Fig. 7) home from the hospital with her newborn baby twins.

22 This red dress is typical of the reform in styling and materials that was accomplished at the Mills. It is of "cut" garment construction, made from a synthetic/wool blend, but it still has good-quality, serged seams and well-crafted finishing details around the neckline and back zippered closing (Anne's daughter still wears it for special occasions today).

Display large image of Figure 10

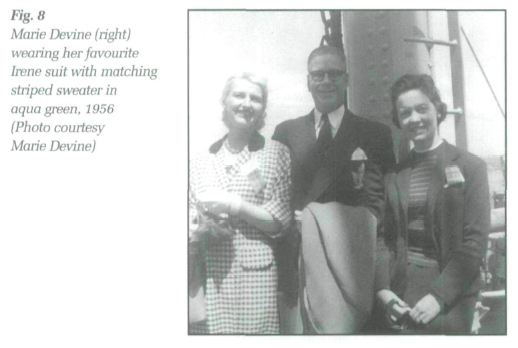

Display large image of Figure 1023 The Irene Knitwear was a big favourite with Marie Devine. Marie, voted one of Canada's "ten best dressed" in 1957, went regularly to Montreal and New York to buy her clothes and she shopped in all the downtown St John's stores. In 1956 Marie had an Irene suit in her favourite shade of aqua green (Fig. 8), and she bought many many more: a "gorgeous" burgundy and grey suit and a black one with a wrap-around skirt...a jacket with black velvet collar and cuffs...sheath dresses and sweaters in air force blue and coral colours. She had lined black wool slacks and an exquisitely fitted turtleneck sweater with a little zipper at the back. Marie says:

Through the sixties period, Ralph Roberts was travelling to New York and to places like Macy's and Gimbals Department stores looking for design ideas as well as sales. He remembers a very positive response from the staff in these stores:

Ralph felt he was being "hung out to dry;" the productivity that was necessary for the Mills to turn a profit was not being supported by Smallwood and consequently Ralph turned his focus to the Newfoundland sales (Fig. 9); he was sponsoring regular Easter Monday fashion shows of the Irene Knitwear in Brigus and at the Argentia and Stephenville bases for the military officer's wives. The clothes were receiving great applause: "American women living on the bases in Newfoundland can't seem to get enough of the knitwear." And it was greeted with "Oh's" and "Ah's" by the women at the fashion show held in St John's:

All this enthusiasm saw the St John's Irene outlet realizing far greater sales than the mainland stores at close to $60 000 in sales.48 But reaching and keeping even the St John's customer was proving to be very challenging. Many society women were, as Ralph Roberts says, "built like Christmas trees" and they were placing custom orders requiring special attention with fittings and alterations. Mary Shaw, the manager of the St John's Irene Store, was becoming frustrated with her job and with the

The Mills were producing to order but keeping a supply of yams in "fashionable" colours was now an impossible task. They had experimented with design and did meet with success for a time, but there really was no one on the team able to create the looks that would bring freshness into each succeeding season, nor was there the personnel experienced in the garment trade that would enable the Mills to respond to the increasingly competitive marketplace. The retailer's margin was too low, sizing and quality was inconsistent, and companies like Mills Brothers and Eaton's were turning down the product as a result; and making matters worse, there was a lack of cash flow and increasingly a lack of credit from suppliers. In the end it all proved too difficult for the management to overcome and the government-owned company found itself unable to continue. The roller-coaster ride lasted until the Brigus Knitting Mills closed its doors in the fall of 1970 (Fig. 11).

Display large image of Figure 11

Display large image of Figure 11 Display large image of Figure 12

Display large image of Figure 12 Display large image of Figure 13

Display large image of Figure 13Other Conception Bay Operations

24 The other Conception Bay factories producing goods for the fashion industry were experiencing the same difficulties with management, design and sales. Major amongst the issues was the high-end type craftsmanship that required additional time and care in the manufacturing process. The goods were attempting to compete in the high-end trade and it was not easy to compete with the quality brand-name labels being sold in the exclusive retail stores of the day, nor were the Newfoundland companies able to compete with the increasing availability of cheaper quality imported Canadian goods that were flooding the Newfoundland market in the post-Confederation period.

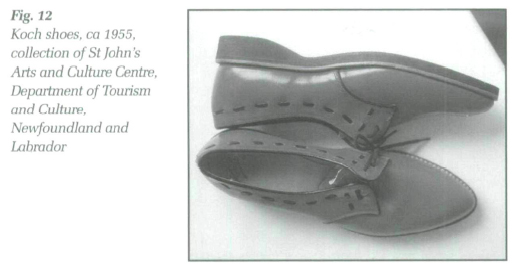

25 Koch Shoes Limited of Harbour Grace produced approximately forty-thousand pairs of shoes in 1956 at between $5 and $14.50 a pair (Fig. 12).50 They carried seventy-five styles under the brand names Koch and Hargrace and became what now is known as Terra Nova Boot with factories in Newfoundland and mainland Canada.

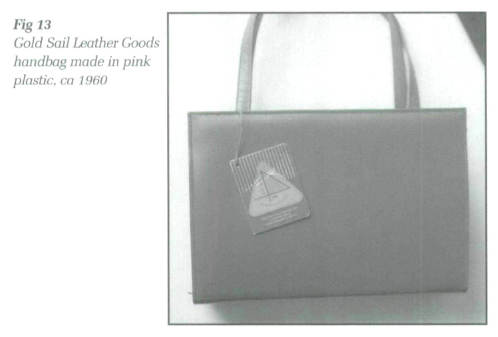

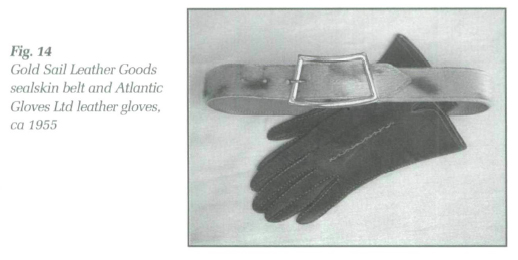

26 Gold Sail Leather Goods Ltd of Harbour Grace was an adjunct to the Koch Shoe factory employing twenty-two persons and in 1956 they produced 16 880 handbags in over 140 different designs retailing at $8 and up. Koch operated at a loss from their inception which, says Little, "reflected die high costs of goods and the amount of hand labour used in their manufacture"51 while the lack of Gold Sail's original high-fashion designs prevented them from selling in the high-priced market. The company eventually closed and finished by producing a line of plastic bags (Fig. 13) for the lower end mass-market appeal.

Display large image of Figure 15

Display large image of Figure 15 Display large image of Figure 16

Display large image of Figure 16 Display large image of Figure 17

Display large image of Figure 1727 Atlantic Gloves Ltd, founded at Carbonear in 1953, commenced the manufacture of men's, women's, and children's hand-sewn gloves by mid 1954 (Fig. 14). The gloves, largely in sport styles, were made from seal, gazelle, moose, sheep, calf, kid and cape in approximately 180 different styles. The company failed due to inefficiencies in production, excessive raw materials and transportation costs, and incompetent management; it closed not long after it began.

28 The leather products made in these three factories were supplied with raw materials produced at the Newfoundland Tannery in Carbonear; at least this was the original intention. But here too there were troubles from the start with inconsistent product quality, unhappy customers and the losses far greater than sales. All five Conception Bay companies were suffering from lack of planning, know-how and adjacency to markets.

Conclusion

29 All of these factory operations were created amidst the great optimism of Post-Confederate Newfoundland. They didn't stand much of a chance; they were competing not only for financial support from the Premier, but for a share in a changing and extremely competitive marketplace. Joey's make-work industrial program had given him more trouble than he had bargained for; the failure of his government to manage the factories properly saw most of them close not long after they began. "Once the plant[s] went into operation the government appeared to lack either the expertise or the incentive — perhaps both — to oversee operations..." says Doug Letto in his study of their demise.52

30 In the context of cultural artifacts the Brigus Knitwear has been until now ignored. Not only do the clothes lack the prestige of age that we desire in our cultural artifacts, but they are a reminder, for many Newfoundlanders, of an embarrassing period in their history; consequently, what remains has little currency in terms of museum collecting. But in the context of the "craft" and the culture of women who were wearing the clothes, the Brigus Knitwear reveals a story that is of great interest nonetheless.

31 The high quality details seen in the knitwear products (the fully fashioned designs, the properly lined pants and skirts, and the quality merino wools) were, at the outset, what distinguished them from others in the market. The clothing was produced in a European model of production that was out of step with the new mass-market strategies against which the products were expected to compete.

32 In terms of the knitwear and cutting edge fashion, rationalizing the comments of mainland buyers, the 'Teutonic" and "old-hat English" designs, with the applause and the "Oh's" and "Ah's" heard from Newfoundland voices poses an interesting question. It is too easy to say that women in Newfoundland were behind the times; the evidence certainly for the elite group doesn't prove this was the case. The Brigus Knitwear was for Newfoundland women a much more complicated affair.

33 Newfoundland was undergoing a profound change in terms of its image in Canada when the Austrian designed knitwear was being sold in Newfoundland stores. In both the urban and rural context the tuxedo jacket, or "Newfoundland Uniform," was overwhelmingly received and it became a symbol that expressed the collective taste of women who were emerging onto the Canadian scene. The initial fashion "edge" of the products gave them a reputation as wardrobe essentials for women in Newfoundland and this carried their popularity for a number of years.

34 The creation of the knitwear and the craftsmanship was a community affair with "so many hands that went into it." Outport people were adapting to an assembly-line process and turning out products that gave them much pride. And one can see that the customers of these factory-made goods were not "consumers" in the sense we think of today but rather fellow Newfoundlanders, family and friends.

35 The tuxedo jacket shows up regularly in secondhand shops across the province, which is a testament to its overwhelming and popular appeal. On occasion you see the Brigus knits being worn today looking as fresh as they did fifty years ago and for many women they are perhaps nostalgic reminders of the excitement of those times.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

36 I would like to thank the employees from the Mills who have helped me with this research, the Centre for Newfoundland Studies and Dr Gerald Pocius for whom this paper was originally written (for his Museums and Historic Sites course at Memorial University of Newfoundland). I would also like to thank Mark Ferguson and Brenda O'Brien for their suggestions with the text.

Ralph Roberts, Cupids, Newfoundland

Eleanor (Roberts) Norman, Bay Roberts, Newfoundland

Marie Devine, St John's, Newfoundland

Anne Kieley Ryan, St John's, Newfoundland

Mary-Catherine Heistinger, St John's, Newfoundland

Gail Weir, Centre for Newfoundland Studies, Archives, Memorial University of Newfoundland, St John's