Articles

Clothes That Are Not Worn (except...):

The Politics of the Clothing Collection at the Museum of Anthropology

Abstract

During the past quarter century, political changes in Canadian society have been reflected in a movement towards more equal relationships between museums and the people represented through their collections. This has been a time of reflection and negotiation, resulting in a very different kind of curatorial practice, one that attempts to respect and include the knowledge and wishes of the people represented. The political relationships around the clothing held in museum collections are particularly sensitive because of the close association of clothing with people.

Résumé

Depuis vingt-cinq ans, les changements politiques survenus dans la société canadienne se reflètent dans la tendance manifeste vers des relations plus égalitaires entre les musées et les groupes de personnes représentés dans leurs collections. Cette période en a été une de réflexion et de négociation, ce qui a entraîné une pratique de conservation très différente, qui s'efforce de respecter les gens représentés et de tenir compte de leurs connaissances et de leurs désirs. Les considérations politiques relatives aux vêtements figurant dans les collections des musées sont particulièrement complexes en raison de l'étroite association des vêtements à des personnes.

Clothing and Power: An Improbable Problem?

1 My role as curator of a worldwide collection of clothing and textiles1 often gives me a feeling of inappropriate intimacy. I feel as though I am in bedrooms and closets, opening the dowry chests and storage boxes of the people who once made, wore, and cared for the clothing. The makers all left evidence of their distinctive individual skills and styles in the physical form and aesthetic character of these handmade garments. When the clothing became worn, they or others added meticulous repairs. On some, the wearers also left the marks of their bodies or their activities: creases where arms were bent, wear marks, fold marks showing how they stored them. This sense of intimacy, of a lingering presence of the people who wore the clothing, remains and is strongly sensed by some people who enter our textile storage.

2 Perhaps it is a reflection of my own interest, but I feel a greater sense of personal presence in clothing than in the other kinds of objects that are in our collections.2 Some garments, carefully structured, reveal the size and shape of the person for whom it was made. Other clothing — saris, sarongs, turbans — took on human form only when their owners arranged them on their bodies. All were worn close to people's flesh, though, as they used them in the course of their lives. Some — and here the association becomes more disturbing — were worn by them in death, and their bodies left evidence of this on the cloth. The great irony is that once they enter the museum's collection, the clothes are no longer worn — except under certain special circumstances.

3 It is my responsibility to ensure that those people who want or need to have contact with the clothing in the collection in order to learn from it, to be inspired by it, or to affirm personal association with it are given this opportunity whenever possible. The words "are given" are politically charged, because in the museum of Anthropology at the University of British Columbia, in its present situation, almost all access to clothing is mediated. We have a visible storage system that gives visitors access to nearly half our collection3 but it includes almost no clothing. Clothing requires protection from light, it requires support, and, to be properly appreciated, it requires a human body, or some approximation thereof. These things are not possible in our visible storage galleries as they are at present, and most of the clothing is kept in a separate behind-the-scenes storage area.4

4 The fact that access is mediated implies that there are political dimensions to the relationships between museum staff and those people who wish to have contact with the clothing because it is under the control of staff. Access must be requested and scheduled; it is not given with entrance to the museum. Because of the structure of the museum and our professional responsibility to protect the collection we, in effect, hold power over it. Many kinds of people make requests for access to various types of clothing and textiles: students in textile studies and costume history, textile artists and designers, academic researchers, and people with special skills and interests, such as members of local fabric arts guilds. With such people, the fact that I must control access to the collection — what they see, when they see it, how they behave around it — is rarely an issue. With few exceptions, they are interested primarily in the physical features of the clothing and textiles — their techniques, their materials, their styles as representative of particular cultures or historic periods. They are satisfied if they are given the opportunity to study authentic clothing and textiles, and almost always leave with enhanced respect for the skills of the people who made them.

5 There are other people who make requests for access. These are the people we call, in our museum terminology and for want of a better term, "originating people." The people who made the clothing were their ancestors, sometimes literally, sometimes in a general cultural sense. In many cases these ancestors parted with their clothing, their household textiles, their regalia, in situations of political and economic inequality. This is especially true of Canadian First Nations. On the Northwest Coast, our local region, communities were nearly stripped of their heirlooms by collectors working for the art market, for museums, or for themselves.5 Contemporary community members often must go to museums to see their own heritage. Museums are custodians of this heritage, and many of us find this position of relative power to be very uncomfortable. It reminds us that the term "post-colonial" is not yet fully appropriate. If it is uncomfortable for us, how much more so may it be for those people who must come to us feeling like petitioners, requesting access to materials from their own heritage?

6 In order to meet the requests of originating peoples and to carry out our museum activities we must negotiate ways of working that minimize inequality and offer as comfortable an environment as possible. These are challenging to achieve in an institutional context in which we are professionally responsible for maintaining control of the collection, and in a physical environment which, unfortunately, has certain features in common with other institutions, such as residential schools, prisons, and hospitals, that, in the course of Canada's history, controlled First Nations and Inuit people in often traumatic ways.6 During the past twenty-five years we have found various ways of working with originating peoples to create more equal and appropriate ways of sharing the clothing that was once theirs. These sometimes involve taking risks that were once considered professionally unacceptable,7 and that even now may require reassessment and reflection.

7 These decisions are made more complicated by the fact that the "originating peoples" whose clothing is in our collection have experienced many different political histories. Their clothing was not always relinquished under conditions of political inequality, resulting in personal and cultural loss. Our collection includes clothing donated by European immigrants, for example, and robes once worn by the elite of Qing Dynasty China, who possessed them in such abundance that their heirs would not be likely to mourn their loss. The relationships between people and their heirloom clothing are complex and diverse, however, and emotional bonds may be strong even when the clothing was voluntarily donated or sold to the museum for its long-term preservation.

8 There are further complications in that not all the clothing we have acquired is old, and that some of it has never been worn. We often purchase contemporary regalia from First Nations artists, for example. These decisions are motivated by our mandate to inform the public that First Nations people are still, now, more than ever a vital cultural presence here (contrary to the beliefs held by many visitors). We have also purchased new and unworn handmade clothing from West Africa, China, and the Andes. Through members of the local Mayan-Canadian community we are just completing the purchase of clothing that was specially woven for the Museum of Anthropology by members of their communities of origin in Guatemala.

9 There are many possible relationships between the clothing in our collection and the people represented by it. The principles that inform our interactions with them, the negotiations that follow from these principles, and the varied and sometimes unexpected outcomes are the subject of this paper. The situations I describe and the solutions we have arrived at are not unique to our institution. Many other Canadian museums are engaged in similar discussions and making related decisions.

"Equal Partners:" Continuing Rights and Issues of Representation

10 When I first started working at the Museum of Anthropology in the late 1970s, the museum's rights over its collections were rarely questioned. The fact that they were associated with people was acknowledged, and the first curator and director made special efforts to build relationships with local First Nations people and with people from other cultures represented in the collections.8 Museum staff did not think it necessary, however, to consult with people when exhibiting material from their heritage or when showing their photographs. The word "permission" was not yet significant in this context. In the political climate of the time, the people whose objects or images were shown did not feel that they could assert those rights. Once their materials had been sold or donated, rights in them were presumed to have been transferred.

11 In 1981, James Nason gave a prescient talk at the annual conference of the BC Museums Association in which he questioned the unfettered right of museums and scholars to collect and study materials from other people's heritage.9 He argued that the heretofore-accepted principle of intellectual freedom could no longer take precedence over peoples' rights to their cultural objects. The previous year the Museum of Anthropology had received what was probably its first protest from a local First Nations group concerning the display of clothing. It had mounted a major exhibition entitled Salish Art Visions of Power, Images of Wealth. Included in the exhibition was a set of spirit dancer's regalia. Such regalia is used in the winter ceremonies that Coast Salish people have been careful to protect from others' view. Earlier in the century they had been willing to appear in public and to be photographed wearing their ceremonial regalia, but in recent years they have become more protective. When local Coast Salish people saw the regalia on display they registered their protest, and the museum withdrew it from the exhibition.

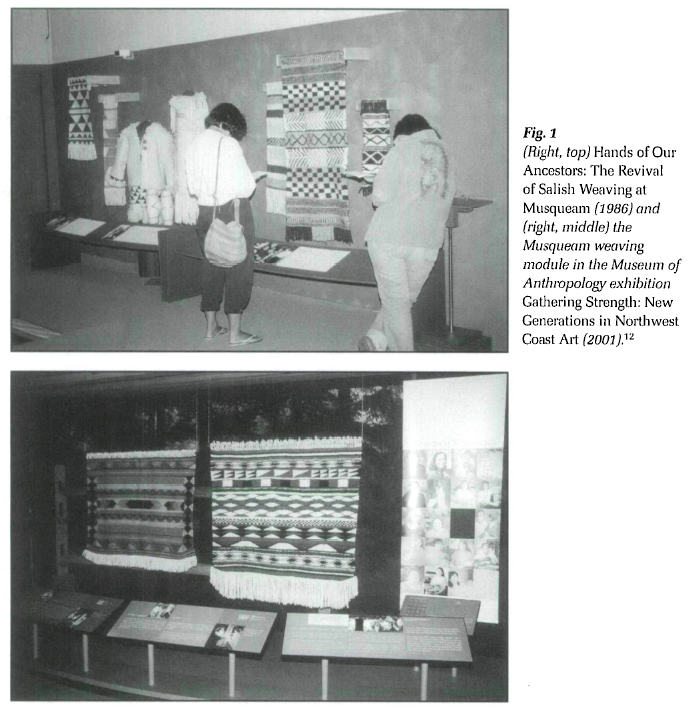

12 In 1986, we mounted another Coast Salish exhibition, Hands of Our Ancestors: The Revival of Salish Weaving at Musqueam. This exhibition grew out of a request that I received in 1984 from Wendy Grant (now Wendy John), the founder of a project to revive the art of Salish weaving at Musqueam, a reserve community close to the Museum of Anthropology. She hoped to be able to bring the art of weaving back into the life of their community, and had just received funding to support a group of women while they learned. They knew of no examples of old weavings in their community, so she contacted me to ask that they be given access to the museum's collection of old weavings. They came back regularly to study them, and I often visited their workshop. Together we decided to do an exhibition of their work. Wendy Grant and her sister Debra Sparrow worked closely with us. They determined that the exhibit would focus on their experience of learning, rather than only showing their finest work, and that their weavings should be hung in the open, not enclosed within glass cases. Each woman's work was shown, interpreted in her own words and with a photograph of her that she had approved. As we reviewed the women's transcripts, the exhibit title emerged from words spoken by Debra Sparrow:

13 At the time this exhibit was done, profound political changes were about to take place in the relationships between Canadian First Nations and museums. The bitter confrontations that focused on the Glenbow Museum exhibition The Spirit Sings (1988) were transformed into constructive action when National Chief of the Assembly of First Nations Georges Erasmus proposed to the Canadian Museums Association that a task force on museums and First Nations be formed to address the legacy of inequality that permeated relations between First Nations and the museums that held so much of their cultural heritage. The final report from their deliberations, ratified in 1992,11 set out guiding principles for First Nations and museums to work together as "equal partners." Among these principles were the recommendations that the importance of cultural objects in museum collections be recognized, that First Peoples have increased involvement in their interpretation and be given improved access to them, and that highly significant and sacred objects, human remains, burial goods, and illegally-obtained objects be repatriated.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1 Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 214 These principles have provided us with welcome guidelines as we strive to co-operate with First Nations individuals, families, and communities in all aspects of museum work. We are continually reminded, too, that issues which for us are work-related may for them be fundamental to their personal lives and cultural survival. Many emotions underlie their relations with us, the custodians of so much of their heritage — anger, resentment, joy, pride. It is essential that we acknowledge these emotions and respect their rights. Finding ways of working together to achieve our agreed-on goals in a respectful way involves regular discussion and negotiation. We must adhere to procedures that ensure that people have given their informed consent to their representation within our museums, and must maintain a commitment to resolving differences when they appear. The roles of museum staff have changed from being experts in charge of their collections to being facilitators of the self-representation of others. Virtually every day we are faced with decisions, large and small, in which this change in our roles is played out.

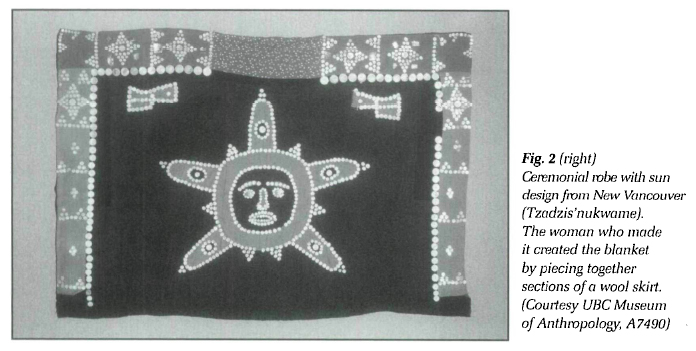

15 In 1993, for example, we were approached by a representative of Canada Post who asked that we nominate a textile from our collection that might be included in their special issue on hand-crafted textiles from cultures and traditions across Canada. We proposed a burton blanket (ceremonial robe), but, in accordance with Task Force principles, could not proceed without seeking permission from the people from whom the robe had come. A further concern was that such robes are worn as ceremonial regalia, and the crest designs on them often express hereditary privileges.13 We knew from information in our files that the robe had come from the community of Tzadzis'nukwame (New Vancouver) on the central coast of British Columbia, but we did not have the name of the family to whom it had belonged. The U'Mista Cultural Centre in Alert Bay provided valuable advice to us on the appropriate protocol in this situation. On their advice, Canada Post and the museum invited people from New Vancouver to attend the celebration launching the stamp at the Museum of Anthropology, and to accept a large rendering of the stamp for display at the U'Mista Cultural Centre.

16 Our working out of decisions such as this one is made easier by the guidelines provided in the Task Force report. The report does not provide a template for decision-making, however. Even within Canadian First Nations we are dealing with many diverse cultures, and our situation is made far more complex by the fact that we hold worldwide collections. Should we try to work as equal partners with all those peoples who are represented in our collections? How do we cross the barriers of distance, differences of language and culture, and different levels of understanding of museums and their place in society? How do we carry this through with objects that are personally sensitive, such as clothing? What about the varying political histories of the groups whose objects we hold? With Canadian First Nations, there is a clear need to attempt restitution for past injustices, but this is not true of all the cultural communities with whom we work.

17 The short answer to those questions is that we do try to work in accordance with Task Force principles in all situations, but that the specific decisions we make inevitably are affected by those difficult questions. For example, over the past several years we have been working intensively with members of the Mayan Education Society in Vancouver. Their members came to Canada from Guatemala, many as refugees fleeing the violence there. Our long-term goal in working together is to produce an exhibition in which the Mayan clothing now being completed in Guatemala would serve to help visitors understand Mayan people's struggle to assert and maintain their identity during centuries of cultural and economic oppression. We have tried to overcome the challenges of distance and language by working with the local Mayan-Canadians. They are providing essential cultural knowledge and also taking primary responsibility for communicating with the weavers in remote highland Guatemala communities so that they can give their informed consent to the representation of their work and their photographs in a foreign country and in an unfamiliar context, a museum.14

Hands of Their Ancestors

18 Our museum work does not always result in tangible projects like exhibitions. Because our clothing collection is not on display, one of my major responsibilities is giving access to that collection. I am contacted at least once a month by classes and community groups who want to examine particular types of textiles. Some classes travel long distances in order to be able to see and study authentic handmade clothing and textiles. They leave looking radiant with excitement at what they have seen, and profoundly impressed with the skills of the people from other cultures and other times who made them. They are especially astonished at the fineness and complexity of the ancient Peruvian textiles, which were made as much as 2500 years ago.

19 The presence of these ancient Peruvian pieces in our textile storage poses a problem, however. Without exception, they are burial goods. Many First Nations people believe that it is dangerous to be in the presence; of human remains or funerary offerings. When First Nations groups enter the textile storage, I often warn them about the presence of these materials so that they can decide whether or not they should be near them. I can also reassure them, however, by telling them that in recent years local First Nations spiritual leaders have performed ceremonies to purify the museum, and to make offerings to those spirits that may be present.15

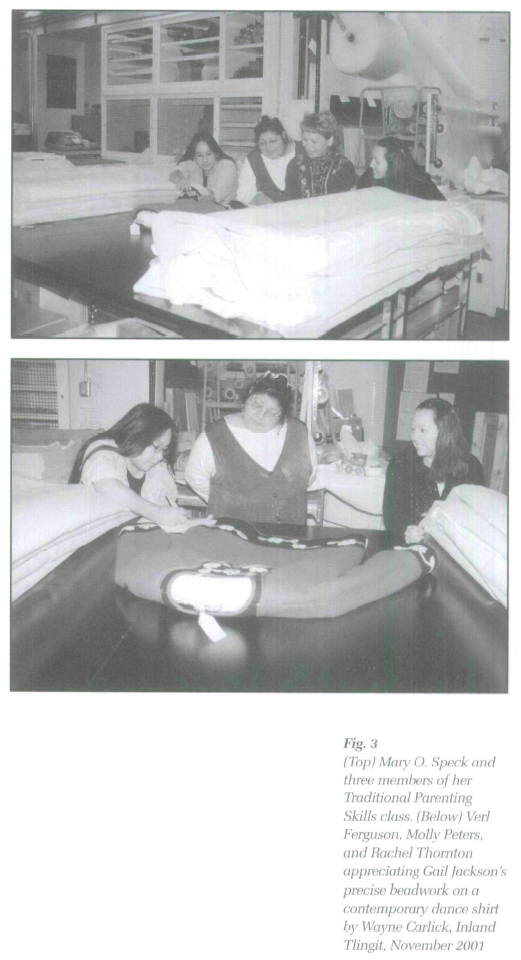

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 320 The First Nations groups who visit are almost always people who want to see the clothing and ceremonial regalia in our collection because they themselves are engaged in learning to make it. The Traditional Parenting Skills class from the Indian Homemakers Association of British Columbia16 and students in Cultural Studies 12 from the Native Education Centre visit the museum regularly. Both organizations serve urban First Nations people of diverse cultural origins. Their instructors have a strong base of cultural knowledge, and elders sometimes accompany them. Some participants in their programs are very knowledgeable about their own cultures, but there are others who were raised away from their own people and may not even know their own origins.

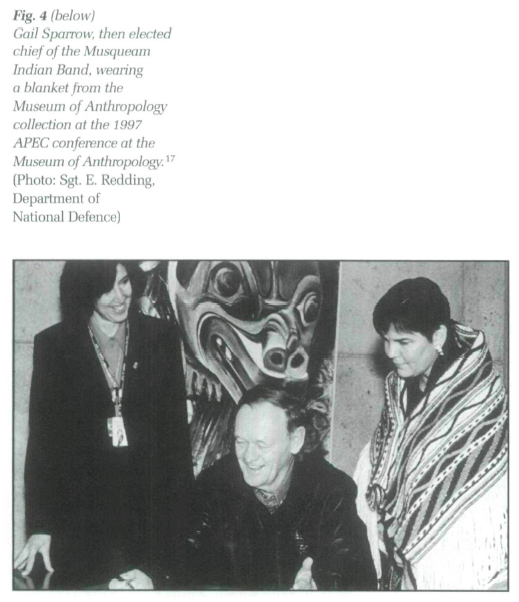

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 421 Normally we do not allow people studying our textiles to touch them. This frustrates them because touch is so important in understanding textiles, but they understand and accept this restriction. With First Nations groups, we do not require this. We reached this decision through discussion among our conservation and collections staff. The decision was informed in part by the principle of restitution — that we could begin to rectify past injustices by acknowledging that these people now should have special rights. It was also influenced by the fact that most of them are making their own regalia. They may have no other opportunities to see and feel clothing made by their cultural ancestors.18 Touch is a fundamental way of making contact, of re-establishing connections, and of learning how textiles are made.19

22 How, then, do we ensure that the clothing is not damaged? We cannot absolutely guarantee this under these circumstances. We do not require gloves because they are such barriers to perception and communication. I usually explain that I wash my hands regularly, and take off my jewellery. I ask that they use their judgement about touching a garment that appears fragile. Our storage methods also communicate subtle messages about preservation. I rarely do more than that, because I do not want to reinforce the image of museums as institutions of control when people are making contact with clothing from their own heritage.20

Clothes that Are Worn

23 When we purchase regalia from First Nations artists and weavers (some of whom do not want to be called artists), it is often with the understanding that the regalia may be borrowed for use in ceremonies. Musqueam leaders, for example, have borrowed blankets that were made by contemporary weavers from their community so that they could participate in important events wearing appropriate regalia, and artists have borrowed back their masks for ceremonies. In each case the staff member responsible for loans talks with the potential borrower to determine ways in which the regalia can be transported safely, kept under secure conditions, and handled carefully. The staff member negotiates a loan agreement with the borrower, and arranges insurance coverage.

24 These loans entail some risk, but in general we believe that this is outweighed by the value to the artist or community of having continued contact with the regalia, which gains a rich life history in the process. If, as sometimes happens, it becomes apparent that it is becoming fragile, then we may have to limit or curtail its further use.

Clothing that Holds Power

25 Some kinds of First Nations regalia are meant to be seen in public, but others are not. We use the museum term "culturally sensitive" for objects that are powerful, dangerous, and/or meant to be seen only in very specific ceremonial contexts. Within our textile storage, we have a system of colour-coding that demarcates this category, and we also have a secluded area within that room where such materials are stored. We endeavour to learn about the presence of culturally sensitive objects in our collection so that we can seek advice on what should be done with them. One very knowledgeable participant in an Indian Homemakers class, for example, said that we should not bring out a Plains skin bag that was covered in red ochre. That bag's storage mount now has the special colour code warning people of this.

26 If regalia can never be shown in public, and must be kept in a highly restricted situation, then we must face the question of why we have it at all. About eight years ago we were approached by a Coast Salish family who had found that we held spirit dancing regalia that had belonged to a family member. After careful deliberation we accepted their repatriation request. At the time of the repatriation, the family held a major ceremony, witnessed by their community members and other guests, to receive the regalia. They invited us, the museum staff who had brought the regalia back to them, to be full participants so that we could be aware of the deep significance of the regalia and the ceremonies in which it belonged.21

Exhibitions — The Ultimate Contradiction?

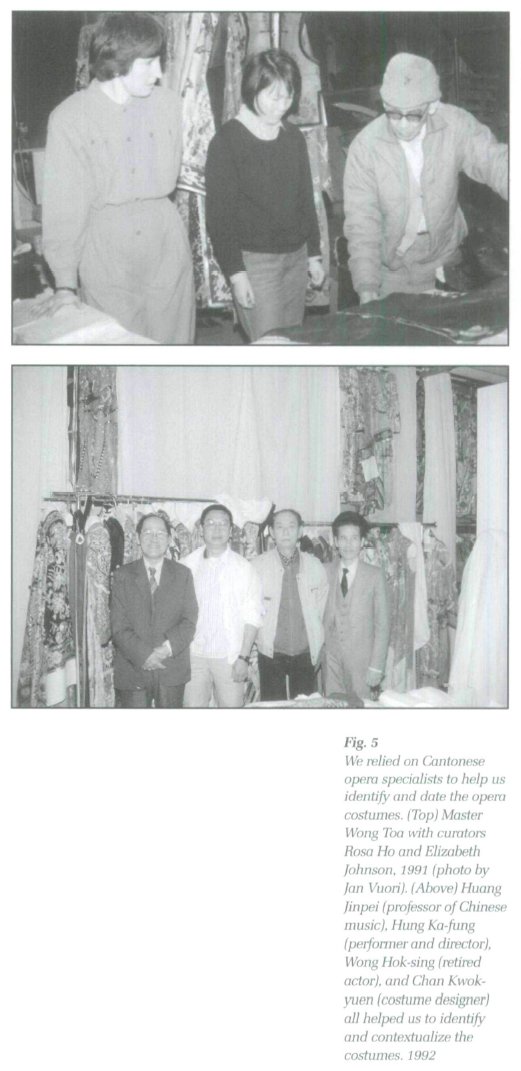

27 We face many contradictions in the course of our work with clothing. Some are inherent in the situations, but we can also create them ourselves. For example, the Museum of Anthropology holds the world's largest collection of old Cantonese opera costumes.22 From my curatorial perspective, their age and rarity meant that they merited a major exhibition, and I argued convincingly for this in my applications for funding. I neglected, however, to consult first with Cantonese opera specialists. When I began working with them on the exhibition I learned, to my chagrin, that they did not value them as I did.23 In fact, Master Wong Toa, a very knowledgeable local Cantonese opera teacher, said to me: "We considered them to be garbage!" I learned from my specialist advisors that Cantonese opera emphasizes novelty and innovation to attract audiences, and that old costumes, being out of fashion, are useless to people whose primary interest is in performance.

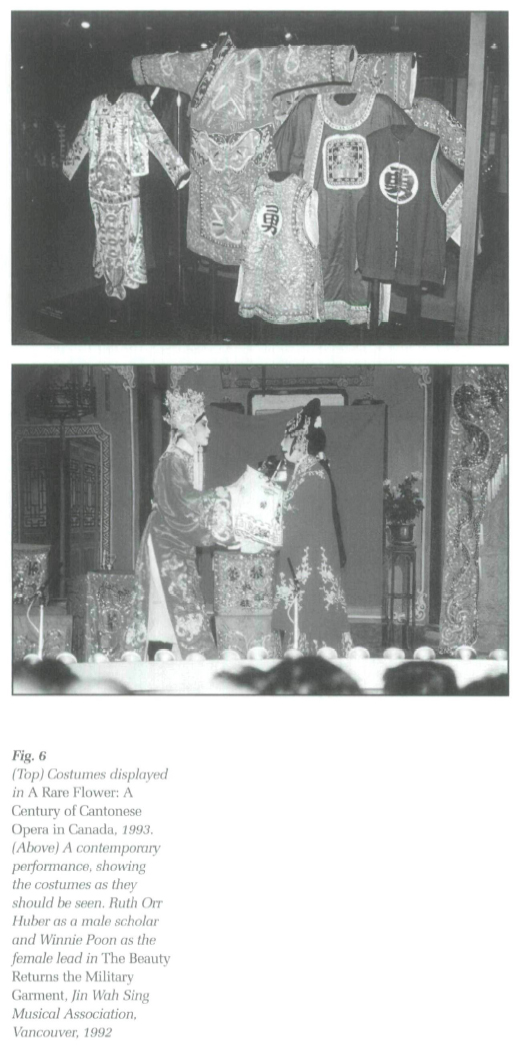

28 These specialists and local performers were generous in sharing their knowledge and helping us to develop the major travelling exhibition A Rare Flower: A Century of Cantonese Opera in Canada, which opened in 1993. As we worked to prepare our exhibition of Cantonese opera costumes, we faced the problem inherent in most exhibitions of clothing: how to show it effectively when it cannot be worn by people? There are, as we know, various solutions to this problem. Good, custom-made mannequins can be effective for showing European and North American historical and contemporary clothing, but even the best mannequins can be disturbing because of their frozen look. There are many risks and challenges in using mannequins to show clothing from other cultures, one of which is ethnic stereotyping in the selection of features and skin colour. Abstract soft forms may work well for certain kinds of wrapped clothing. Discussing this problem with people whose clothing is being exhibited is challenging because we are asking them, in effect, to find a way of representing themselves.

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 529 Two of our Cantonese opera advisors stated unequivocally that the costumes should be shown on fully-detailed mannequins. Master Wong Toa explained that they should be arranged to represent a scene from an opera. I am sure we disappointed him and others when we could not do this, despite the fact that we tried to show how the costumes were used through historical and contemporary photographs and a video of a contemporary performance. I did my best to explain to them that it was impossible to use mannequins because the costumes are incomplete and because we do not have information on the makeup and hairstyles used in the early twentieth century. Furthermore, the costs of making such mannequins, packing them, and shipping them in a travelling exhibit would have been prohibitive. Our solution of displaying the costumes as textile art rather than clothing was unsatisfactory to the people most closely connected to them.

30 We had several discussions about the challenge of exhibiting clothing as we worked with our Maya advisors to plan our exhibition of the clothing that was being woven in their communities. We showed them a number of examples of display techniques, and their conclusion was that mannequins would not be appropriate, arguing that they did not want the exhibit to look like a store. Some of the examples we showed were disturbing because they were too naturalistic. Others, more abstract, were appropriately unobtrusive, but could not be used with garments that were cut and constructed. We decided, ultimately, to display the garments flat, but placed in appropriate relationships to each other, and to use photographs to show how they look when worn by people in Guatemala.

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 6Curators and Clothing

31 As I continue in my role as reluctant mediator between people and the clothing that is in our collection, I am continually surprised at the richness and complexity of this relationship. I feel privileged to participate in these projects because of the opportunities they give me to learn about the many meanings that clothing can have for the people most closely associated with it. The politics of our interactions are made clearer by the principles that now guide us, but they continue to present surprises, challenges, and opportunities to learn and to reflect.

I would like to thank those people who gave permission for their photographs to be reproduced in this article. Miriam Clavir gave valuable comments on the draft text.