Articles

Toronto Blueberry Buns:

History, Community, Memory

Abstract

Unlike other Jewish memory foods such as homemade gefilte fish or matzoh ball soup, blueberry buns are virtually unknown to Jews living outside of Toronto. Yet these sweet, yeasty baked goods are a well-loved treat that trigger memorial narratives for those who remember eating them in downtown Toronto between the 1930s and the 1950s. For those who grew up during that era, blueberry buns represent childhood, summertime and visits with friends and family. This paper will explore the cultural significance of blueberry buns, as well as attempt to solve several mysteries that surround this Toronto treat: where did the recipe come from? Why did the buns become so popular? And finally, why have these treats remained solely within the boundaries of Toronto?

Résumé

Contrairement à d'autres mets appartenant à la mémoire collective juive, comme le poisson gefilte ou la soupe aux boulettes de pain azyme maison, les brioches aux bleuets sont pratiquement inconnues de la communauté juive à l'extérieur de Toronto. Ces pâtisseries au levain sont une gâterie appréciée qui déclenche un flot de souvenirs chez ceux qui se rappellent en avoir mangé au centre de Toronto dans les années 1930,1940 et 1950. Pour tous ceux qui ont grandi à cette époque, les brioches aux bleuets représentent l'enfance, l'été et les visites aux amis et à la famille. Cet article étudie la signification culturelle des brioches aux bleuets et tente de lever quelques-uns des mystères entourant cette gâterie propre à Toronto : la provenance de sa recette, le secret de sa popularité et la raison pour laquelle elle est circonscrite à Toronto.

1 Summer afternoon visits to Bubby's apartment habitually included a much-anticipated stop at the nearby Health Bread Bakery, where we stocked up on Jewish treats. What I remember most were the blueberry buns. Though Bubby, my maternal grandmother, was an incredible baker — poppy-seed moon cookies, apricot rugelach, and honey cake — she enjoyed the indulgence of these store-bought treats that she no longer made herself. I remember watching Bubby opening the bakery boxes, cutting the buns in half, and arranging the goodies on a serving plate. My siblings and I enjoyed the sweet buns with glasses of milk, while Bubby and my parents drank tea.

2 I never thought much about blueberry buns — other man as something we ate during these visits with Bubby, or when occasional visitors brought them to our home, or once in a while when Mom picked up a half dozen at the bakery for a special treat. In retrospect, they did not seem to be particularly Jewish, nor were they particularly unique. The idea for this paper came about two years ago, when I was living in New York and working at a small Jewish museum. A conversation with Matthew Goodman, a colleague who was the "Food Maven" for the legendary Forward newspaper, turned into a discussion about Jewish food items that are unique to certain places. For example, egg creams in New York; or bagels and smoked meat in Montreal. As I am a native Torontonian, he asked me what Jewish food was unique to my hometown. I was stumped. At first I could not think of any such item—but suddenly, I thought of Bubby, the Health Bread Bakery, and blueberry buns. I asked him if he had heard of a blueberry bun. He was clueless — and I knew that I was on to something: that perhaps Toronto's well-loved blueberry buns were virtually unknown to Jewish bakeries outside this Canadian city. After conducting my own informal research, I learned not only that Jewish bakers in New York had never heard of such a thing, but also that the blueberry bun was an unfamiliar delight for Jewish friends and colleagues who had come from other North American cities.

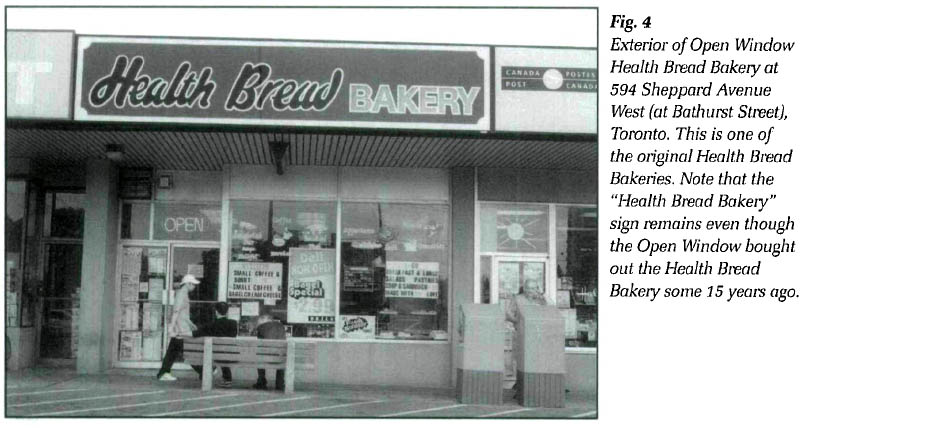

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 13 I was intrigued. When I went home to Toronto I continued my quest, wanting to be certain that they were indeed "Jewish." As they were a specialty item of Jewish bakeries, I concluded they were. It also became clear that they were a "memory food" for many Toronto Jews who grew up in the city between the 1930s and 1950s. Excited with my findings, I reported back to Matthew Goodman, and encouraged him to write an article on Jewish Toronto's distinctive bakery treat. He wrote "Behind the Baking of the Blueberry Bun, the Bagel of Toronto" in the April 27, 2001 edition of the Forward. Consequently, I wanted to pursue this topic on my own: to think about and to reflect upon this food item that has regional, ethnic, and nostalgic connotations for members of the Toronto Jewish community. I will explore its meaning as a memory food; its role as a gift item; and finally, I will attempt to trace the history of the blueberry bun.

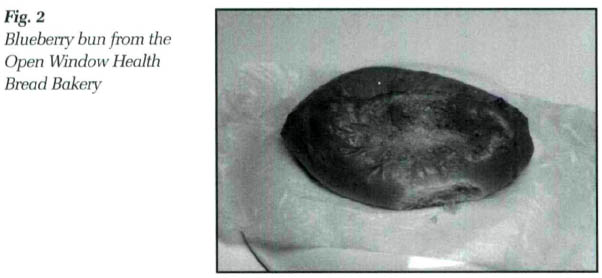

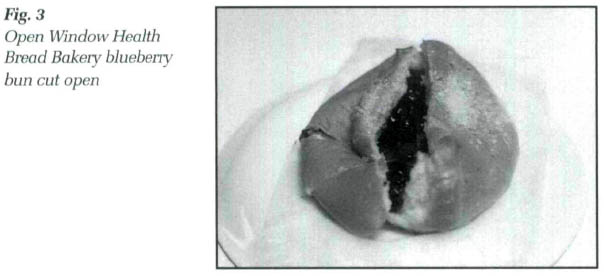

4 A blueberry bun is made from sweet yeast dough that is filled with fresh cooked blueberries. A baker of these buns rolls out the dough, covers it with blueberries, folds the dough over, and twists the corner ends to keep the blueberries from spilling out. Before they go into the oven, the tops are brushed with egg white and large sugar crystals. Ready to eat, they are oval-shaped, about six inches long, and three inches wide (Figs. 1 to 3). The blueberries are completely contained in the dough — the closest thing they resemble perhaps, is a pizza pocket, and like pizza pockets, they are messy to eat. Seventy-five-year-old Harry Moran recalls the blueberry buns of his youth: "They were unbelievable. You know some of them were so filled up, by the time you ate them, your whole face would turn purple!"1 Harry's narrative focuses on the blueberry buns of his youth; however, when he compares tire buns of the past to those of today, he favours the buns engrained in his memory: "Some of the crap that they have today — I think they must squirt it in with a squirter!" In this way, when Harry describes blueberry buns, he also demonstrates a nostalgic longing for the "old days" — when food was of better quality, and an abundance of blueberries was put in the buns. Harry buys blueberry buns today, but not regularly. When I ask him how often, he says:

5 For Harry, blueberry buns are an item of the past, a memory food. He cannot eat one, or even speak of one today without comparing it to the blueberry buns he remembers from his youth. Often, the remembrance of food is tied into a longing for the past — not always for the "thing" itself; but sometimes it is a "sadness without an object."3 The blueberry bun disappears in time, and all that is left is time itself.

6 The "past" is not only youth, but also the "good old days." Harry and his contemporaries were children of hard-working immigrants. Yiddish was their first language, and within their small neighbourhoods of downtown Toronto, the world was Jewish. Eating Jewish food from that era compresses the boundaries of time, bringing folks back to the old neighbourhood. Elizabeth Ehrlich describes her father's similar experience when he eats his Aunt Dora's honey cake:

7 As these children of immigrants became more assimilated into North American society, they lost many of their "old" ways, often including language, custom, religion, and tradition. Food however, is usually the last thing to go; and therefore, it remains a vestige of ethnic identity. Jack Kugelmass explores Jewish identity through food in his essay, "Green Bagels: An Essay on Food, Nostalgia, and the Carnivalesque." He suggests the significance of retaining ethnic knowledge is constantly decreasing, and as a consequence, people are losing the ability to participate in rituals. Furthermore, he writes: "ethnicity becomes conflated with the past, tradition is seen as 'something we used to do' and is encapsulated in a host of cultural productions from restaurants to books to plays to films."5

8 While blueberry buns are not necessarily "cultural productions," they nevertheless perform on a more personal level to invoke Jewish nostalgia, the past, and "something we used to do." Blueberry buns however, unlike gefilte fish or matzoh ball soup, are not a symbolic food for most Eastern European Jews; on the contrary — while they are typical of Eastern European Jewish bakeries in Toronto, they mysteriously do not appear in Jewish bakeries in other cities. When I ask Lorna Stein, a 60-year-old native Montrealer, about blueberry buns, she asks me right back, "Blueberry buns? I never ate a blueberry bun in my whole entire life, I can tell you."6 Not only has Lorna never eaten a blueberry bun, but also the food item has never entered her realm of existence. "I could go to a Jewish bakery here," she says, "and they wouldn't know what I was talking about." Nevertheless, she has become curious of the Toronto treat. "I'll ask around," she tells me.

9 Most people agree that blueberry buns were created in Toronto at the Health Bread Bakery, but there are still several unsolved mysteries surrounding this Toronto treat: where did the recipe come from? How did the buns become so popular? And finally, why have these treats remained solely within the boundaries of Toronto? Looking for the answers — or at least some insight into these questions, I met with Kip Kaplansky, a son of Annie Kaplansky, founder of the legendary Health Bread Bakery (Figs. 4 to 6).

10 Annie Zuckerman Kaplansky and her two children moved to Toronto from Rakow, a small town in Poland, in 1913.7 Like many Eastern European Jewish families, her husband had arrived in Toronto a few years earlier in order make enough money to send for his wife and children. The years 1880 to 1914 mark the largest wave of immigration of Eastern European Jews to North America. Like hundreds of thousands of other Jews, the Kaplansky family came to North America in order to escape religious persecution and pogroms; and to begin a new life of freedom and success in the "Golden Land." In 1928, Annie opened the first Health Bread Bakery in Toronto. She knew about bread, as her father was a miller — but this was her first venture into the business of baked goods. Bakeries, groceries and corner stores were common professions for Jewish immigrants because little capital investment was needed; often the families lived at the back of the store, or in an apartment upstairs.

11 Annie's son, Morris Ben, known as "Kip," quit school at the age of fourteen to help his mother run the bakery. At that time, it was not uncommon for youngsters to drop out of school at an early age, as people were poor and families needed all the help they could get. "We were the first Jewish bakery that opened and served more than bread," 88-year-old Kip Kaplansky recalls. "The other Jewish bakers in Toronto, all Jewish bakers, just made bread and buns. None of them made cakes, and they didn't make anything else."8 In the beginning, the Health Bread also only made bread and buns, but soon Annie realized that her bakery could be different from the others. It was not long before other Jewish bakers caught on and began to sell cakes and pastries as well. Not only was the Health Bread Bakery the first to sell items other than bread, but Kip also believes that his mother was the first baker to present blueberry buns to the public. He remembers, "when we started making them in the bakery — that was really something, they just spread like wildfire!"9

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4 Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5 Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 612 I asked Kip if he knew the origins of the recipe, but he did not know. "Now I'm not one hundred percent sure about this," he says, "but I think my mother used to make blueberry buns in Poland."10 He explains that wild blueberries grew there, and that his mother must have brought the recipe with her from the Old Country. Blueberries as we know them, however, are native to North America, so perhaps the wild blueberries that Kip talks about are a European species of the berry. Curiously, Kip recalls his customers asking for the buns by several Yiddish names, one being yagedes. According to Weinreich's standard Modern English-Yiddish, Yiddish-English Dictionary, yagedes is translated simply as "berry," while "blueberry" is translated as schvartz yagedes.11 And oddly enough, the other Yiddish name for blueberry buns, recalls Kip, is shtritzlach, a word which does not mean blueberry buns either, but rather, some other type of fruit cake.

13 Matthew Goodman's article points out that while shtritzl (singular) does not appear in Weinreich's classic dictionary, it does in fact appear in Alexander Harkavy's more obscure Yiddish-English-Hebrew dictionary, where it is defined as "currant cake."12 Thus, Goodman suggests, perhaps Annie Kaplansky used her old recipe for currant cake, and substituted the currants from her homeland with the abundant blueberries found in Ontario. As immigrants adapt to new countries, their traditions often undergo an adaptation as well. Food writers Kaplan, Hoover, and Moore observe: "Ethnic foodways are rarely identical to those in the homeland. In the first place, specific ingredients may be unavailable in the new land; substitutions are inevitable."13 In this way, the Jews of Toronto, with the innovation of Annie Kaplansky, enjoyed a variation of shtritzlach, different from what was known in Poland.

14 Just like there are house types, tale types, and ballad types — here is a case of food types exemplified by shtritzlach. Goodman also points out that shtritzl appears in Nahum Stutchkoffs Yiddish thesaurus, listed under the grouping "challah" (Sabbath bread); along with rogal, "a horn-shaped loaf of bread," and podskrebik, "a loaf made of dough scraped from the trough."14 Accordingly, this grouping suggests the Polish variant of shtritzl is physically closer to a loaf,1 unlike its Toronto variant, the blueberry bun, which is similar by way of ingredients: flour, sugar, and berries, though it looks more like a pastry than like a loaf. The naming of the thing is somewhat confusing—the Yiddish and English names for the same food item could describe different treats: buns versus cakes. I wondered perhaps, if the name shtritzl was a misnomer for the thing known in English as the blueberry bun. But the emphasis of commonality between the two is the ingredients, rather than the form into which the ingredients are baked.

15 Analogously, material culture scholar Henry Glassie describes his experience during architectural field work: "I have taught myself to concentrate on form, but everywhere I go the people whose houses I study classify buildings by materials."16 In this way, clues to the origins of blueberry buns are in the ingredients of these baked goods and their variants, rather than in the form itself. To use Glassie's comparison, an artifact is a story — with text, form and meaning. Unlike a story, which moves in one direction, the artifact incorporates "spatial experience."17 Accordingly, blueberry buns tell the story of a particular generation of Toronto Jews; while the "spatial experience" is historic downtown Toronto and the once abundant Jewish bakeries found there.

16 The European shtritzl may be traced to yeast breads that were popular in southwest Germany, Alsace, and Austria. Food historian John Cooper explains the Yiddish term kugel (pudding) derives from the aforementioned countries' yeast breads, originally called kugelhopf and gugelhupf.18Furthermore, Cooper notes, Polish-Jewish cuisine was strongly influenced by recipes of southern Germany. Cooper explains:

17 Shtritzlach, and in turn, blueberry buns, could have been variants of the kugel described above, still commonly eaten at Sabbath meals. Cooper's description for these yeast breads also fits into the same "ingredients" category as the blueberry buns: yeast dough and raisins (think currants/blueberries). Furthermore the yeast breads and kugel, like blueberry buns, were baked in a round form.

18 Like kugels, blueberry buns also were a popular food item commonly eaten on the Jewish Sabbath. Sixty-nine-year-old Torontonian Ann Moran recalls that Fridays and Saturdays were special days in her youth. These days of course, represent the Jewish Sabbath, or Shabbos. In Arm's home, blueberry buns were enjoyed on Saturday mornings, because on this day of rest, observant Jews did not use electricity, including stoves and toasters; and therefore, a blueberry bun or a danish were practical alternatives to toast in the morning. Ann explains, "You couldn't light the fire for toast. You couldn't have coffee. So we always had a piece of cake and a glass of milk for breakfast on Saturday morning."20 Ann's recollection of eating blueberry buns on Saturday mornings also triggers fond memories of Sabbath customs:

19 Many Jewish Torontonians of Ann's generation recall the Sabbath as a particularly special time. Shirley Granovsky grew up with three generations under one roof, hard times, but happy: "Upon arriving home from school on Friday, I was met by the delicious aroma of the Shabbat meal mingling with the clean scent of wax and polish. Everything shone."22 Both Ann and Shirley contrast the past and the present by remarking that regardless of financial hardships, their families made the most of what they had, particularly for Sabbath meals. They look to the past with affection, despite the troubles they endured. According to Susan Stewart, "Nostalgia.. .is always ideological: the past it seeks has never existed except as narrative."23

20 The first Health Bread Bakery was located at 530 College Street, in a neighbourhood where many recent Jewish immigrants — including my own grandparents — had settled. The Kaplansky family lived upstairs from the bakery. Soon thereafter, the business moved just a few blocks away to 630 College Street. Harry Moran grew up nearby, and recalls the many bakeries in the neighbour-hood. Each store had its own specialties — the Health Bread's of course, were blueberry buns, In the narrative below, Harry recalls picking up a half-dozen blueberry buns for the weekend, and also reminisces about the other bakeries nearby:

21 There were many Jewish bakeries in Toronto, and each one was known for particular goods: pastry, bread, or specialty items. Ann Moran remembers that people were "very discriminating" about whom they bought their bread from. It appears that people were also careful about whom they bought their blueberry buns from as well.

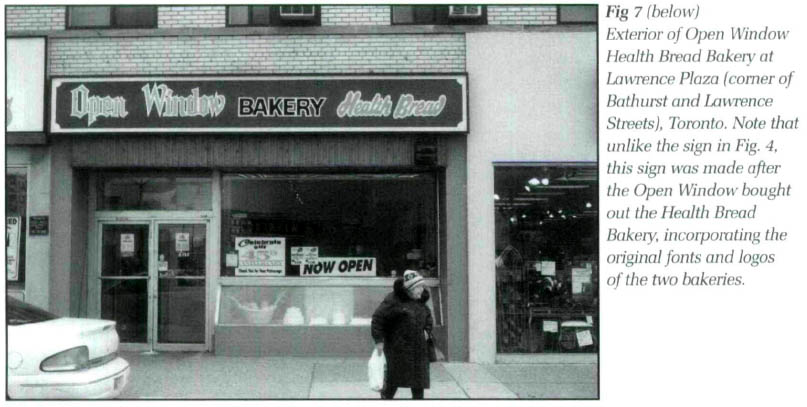

22 Rafi Kosover, the third-generation owner of the celebrated Harbord Bakery, muses, "We were jealous of the Health Bread Bakery and their delicious blueberry buns...I used to tell my dad — 'We need to make blueberry buns too!'"25 But the elder Mr. Kosover did not dare to sell the coveted item — "They were difficult to make," Rafi explains, "and my father knew he could not produce them like Health Bread's."26 Other bakeries however, were more daring, but were chastised by customers because of their inferior blueberry buns. Max Feig, the owner of another Toronto Jewish family-owned baking institution, the Open Window Bakery, in business since 1957, reminisces: "In the old days, people always used to say to us, 'How come your blueberry buns can't be like Health Bread's?' Now we use their recipe."27 Fifteen years ago, the Open Window bought out the Health Bread Bakery. Needless to say, the famous blueberry bun recipe was sold as part of the deal (Figs. 7 and 8).

Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 723 Though customers used to complain about the Open Window's blueberry buns, customers at other bakeries were not so fussy. Ann Moran worked at the Crown Bread Bakery as a teenager in the mid to late 1940s. The Crown Bakery was located at Augusta and College Streets, "where everyone from my era grew up — I'm sixty-nine years old and that's where everyone grew up," Ann contends. This bakery too made blueberry buns — and as far as Ann remembers, no one complained about them. Blueberry buns were the "hot seller." She recalls:

24 Ann explains that blueberry buns were a popular weekend treat for Jewish families who spent summers at their cottages. "Blueberry bun season" coincided with blueberry season, which occurs between the months of May and October, though the month of July was the height of the season. In the beginning, Kip Kaplansky recalls making blueberry buns only in season, using fresh berries. However, the customer demand was so great, that they started to sell them year-round, using frozen berries. Nevertheless, the buns are most popular during "fresh blueberry time," (Fig. 9) and people's memories of blueberry buns today remain located in the summertime. When I asked Ann what blueberry buns meant to her, she said:

25 Here blueberry buns are remembered as commonly brought gift items when visiting friends and family at their cottages. Even now, this tradition is practised today — "you'll always need to go over for the blueberry buns," Ann insists. As I pointed out at the beginning of the essay, my own memories of blueberry buns are of bringing them to my Bubby's apartment when we went to visit her.

26 Gerald Pocius writes about the meaning of food during home visits in Calvert, Newfoundland. He explains that visits "usually involve the offering of some kind of food or drink to the visitor. Generally, the structure of many visits involves an exchange of news for a certain period of time, followed by this offering."30 In Calvert, the host makes the food offering. For Toronto Jews, when blueberry buns are involved, the visitors make the offering. The gift today is memories of the thing itself: "Health Bread put in blueberries to beat the band,"31 Ann Moran wistfully remembers; as well as memories of youth and the "good old days." It is a food gift that facilitates a narrative exchange steeped in memory.

27 In Marcel Mauss' classic work. The Gift, the author ponders the meaning of gift and exchange in archaic societies. He asserts, "To refuse to give, to fail to invite, just as to refuse to accept, is tantamount to declaring war; it is to reject the bond of alliance and commonality."'32 The gift of blueberry buns demonstrates a "bond of alliance and commonality" between Toronto Jews for several reasons. Firstly, the buns were bought from a Jewish bakery, so the receiver can be assured that the ingredients coincide with Jewish dietary laws; they are "safe" to eat and to bring into the home."33 Secondly, by Jewish tradition, it is highly regarded to offer a gift of food. Amy Shuman illustrates the latter point in her article about Orthodox Jews who give food baskets as gifts during the holiday of Purim. The author refers to a story about a Rabbi and his wife who both give gifts to the poor. While the Rabbi offers money, the wife bestows prepared food; and thus, she is considered more righteous.34 Thirdly, the giving of blueberry buns implies a particular social relationship between the giver and the receiver. In most instances, to share blueberry buns today is to share a common past.

28 This gift relationship however, has changed over the years. In the "old days" blueberry buns were gifts, common enough, from the local bakery. The shared relationship was that of sharing a tasty Jewish bakery treat. Today the gift is not simply a gift of food, but rather, one that brings the recipient and the giver back to the days of summer and youth in downtown Toronto. Kip Kaplansky tells me he often is approached in public by his past customers, "Oh the blueberry buns," they exclaim, "were wonderful! " Kip knows that people can purchase and enjoy them today, but the taste they are craving is that of nostalgia.

Display large image of Figure 9

Display large image of Figure 929 In the introduction to The Taste of American Place, Shortridge and Shortridge suggest that Americans miss having a sense of identity; and are attempting to remedy this by way of "neolocalism," a phenomenon described as "a renewed commitment to experiencing things close to home.35 Americans have created a new sense of community through cultural expressions, including the "consumption of regional foods."36 In this way, blueberry buns not only bring people back to the past, but also to a particular place in the past: downtown Toronto. Ann Moran talks about her friend who brings blueberry buns to her sister, a native Torontonian who lives in California: "Bernice's sister lives in Los Angeles, and when [Bernice] goes to visit, she always takes a dozen blueberry buns there."37 For Bernice's sister, blueberry buns represent Toronto, her childhood home. When the sisters share the buns in California, they are transported back to their youth in Toronto. Bernice is not unique in transplanting tastes for memories: Marie MacLean, the counter woman at the Bagel Haven Bakery and Café — arguably the place that makes today's best blueberry buns — tells me that customers often request a dozen or more blueberry buns to be shipped to out of town relatives from all over, including Chicago, Philadelphia, Los Angeles, Winnipeg, and even Georgia38 (Fig. 10). Sandy Offenheim, a blueberry bun aficionado and a regular Bagel Haven customer insists that the bakery's blueberry buns are the closest taste to the blueberry buns of her childhood. Her transplanted relatives would agree: "My uncle from Chicago always said, 'I have to get the blueberry buns' when he'd come to visit. And when I would visit my American relatives. I knew that would be the best treat I could bring them."39 Wherever they end up, the blueberry buns at Bagel Haven fly off the shelves."I had six trays at nine o'clock this morning, now I'm down to two," MacLean remarks. Telling me this on a Thursday at noon means she has sold approximately sixteen dozen blueberry buns in just three hours. The bakery, located in an outdoor plaza on the suburban corner of Bathurst and Steeles, is full of customers — mostly Jewish and over fifty, many of whom grew up eating the original Health Bread blueberry buns as youngsters in downtown Toronto.

Display large image of Figure 10

Display large image of Figure 1030 Most often, when people reminisce about blueberry buns, they remember them as treats bought from the bakery. This is the case for Harry Moran, who has particular memories of buying them at the Health Bread, even though his mother occasionally made them herself at home. Unlike other Jewish memory foods, like Bubby's gefilte fish, Mom's brisket, or Grandma's mandelbroit cookies, the longing for blueberry buns does not recall these treats as homemade. Henry Glassie remarks, "Nobody, we say, makes things by hand anymore. Now it is all industrial production and consumption. It can feel like that because we are consumers more than creators."40 Glassie's words suggest that "we" — North Americans — lament a time when things were made by hand. The longing for the blueberry bun, however, is for the thing that is mass-produced. Usually when folks talk about blueberry buns, rather than expressing a longing for "home" and mom's baking, the associations are with a more general longing for the past: its bakeries, and the ritual of purchasing the buns. When I asked Harry Moran about his associations with blueberry buns, he said, "Blueberry buns? It was something for people who had cottages up in Jackson's Point. Every weekend they would go — you'd wait in line actually at Health Bread, and they'd all bring back boxes of blueberry buns."41 Hence, although Harry's mother also baked them at home, what was dear to him was the purchasing of the blueberry buns as a community ritual. His memory is not only temporal, but spatial as well.

31 The anthropologist Joëlle Bahloul writes on spatial memory. The following quotation refers to the remembrance of a house, but it can be applied to other spaces as well, like the Health Bread Bakery: "The past is a house; it has an architectural structure. The house is transformed by memory into a text, and the memorial narrative into a house."42 In this case, Harry's memory focuses more on the experience of buying blueberry buns than on the actual blueberry bun eating experience. Kip Kaplansky's "memorial narrative" recalls a similar ritual of people lining up to buy the buns: "When the kids went to camp in the summer and the parents would go up to visit for the weekend, [the parents] would line up at our bakery to buy six dozen buns!"43 Kip remembers those summer days as the busiest the bakery had all year. "Some days," he recalls, "my mother and I worked for twenty hours straight — making and selling blueberry buns." On those busy weekends, they often sold an incredible two thousand dozen blueberry buns — "just in the one store on College Street... A staff working all that time just making blueberry buns!"44 At close to two dollars apiece today, customers do not buy the buns in the same quantities. In the 1930s however, "when the blueberries were cheap," Kip remarks, "they used to come in and buy a dozen for thirty cents. So it wasn't expensive. They don't buy them by the dozen now."45

32 What I find most intriguing perhaps, is the shift that occurs when certain foods that are affiliated with regions or places become associated with a particular ethnicity: like the German cake described earlier in the essay that was the basis of a Jewish kugel; or vice versa: when foods identified with certain ethnicities become associated with a particular place, for example, when the egg cream — a soda fountain drink invented by Jewish candy store owners, and Jewish by association — became "New York." Likewise, certain food items shift from having an ethnic, or regional identity, to become part of a "melting pot," incorporating more than the original ethnic group or place. In her spring 1998 graduate seminar, "Food and Performance," at New York University, Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett illustrated this phenomenon with relation to bagels. She said: "In New York the bagel is Jewish; in Oregon it is New York; in Japan it is American."46

33 What is the blueberry bun then? Is it regional, ethnic, or both? Did it originate in Poland or Toronto? If the recipe hails from Poland, why did its popularity not spread to other parts of North America with the Jewish immigrants who opened bakeries in other cities? Unfortunately, I do not have answers to these questions, but I raise them to demonstrate how complicated an object can be. The meaning of blueberry buns lies in how they are perceived by those who remember them and enjoy them today. As Henry Glassie conveys: "Meaning is the sum of relations between objects and people. Accounts of meaning can begin anywhere in the object's history, though I think they are best begun in creation. "47 In this paper, I have attempted to consider the meaning of the blueberry bun by trying to trace its history to its original form. Though I was not able to accomplish this task, I found variants of possible earlier versions of shtritzlach. The significance of the bun however, is not contained in the origins of the object — where it was invented is interesting, but it does not convey the meaning of the thing itself, for as Glassie remarks: "All objects exist in context."48

34 For Toronto Jews who grew up between the 1930s and the 1950s, blueberry buns today are not simply treats from the local bakery; rather, they represent a yearning for the past — for youth, summertime, neighbourhood shops, and visits with friends and family. Though blueberry buns are available today, they have yet to gain the same popularity they once had. When I asked friends and relatives in their 20s and 30s about blueberry buns, the unanimous response was, "Oh, you should talk to my parents — they'll tell you stories." Thus, though eaten and enjoyed today, blueberry buns are primarily a memory food, a thing of the past. In this way, they are cultural artifacts. The art historian/material culture scholar Jules David Prown explains that an artifact "is something that happened in the past, but, unlike other historical events, it continues to exist in our own time."49 I am not certain if Prown intended to include food in this description of artifact, but clearly blueberry buns fit into his definition. Though presently foodways is on the periphery of material culture scholarship, it is hoped that future studies will more readily examine food as artifact. As this paper has revealed, the exploration of regional and ethnic food items—Jewish Toronto's blueberry buns—offers significant insight into the history and culture that surrounds them.

35 The following is Matthew Goodman's recipe adaptation for shtritzlach from the Open Window Bakery.50

1 package active dry yeast

1/2 cup warm water

3 cups flour

1/3 cup sugar

1 tsp. salt

3 tbsp. vegetable shortening

2 eggs

1/2 tsp. vanilla

2 cups fresh or thawed frozen blueberries

1/2 cup sugar

1 tbsp. corn starch dissolved in 1/4 cup water

1/4 tsp. salt

1 beaten egg plus 1 tsp. water for egg wash

sugar for sprinkling

- In a small bowl, dissolve the yeast in the warm water. Let stand until mixture begins to bubble, about 5 minutes.

- Sift together flour, sugar and salt. Place in the bowl of an electric mixer. Add shortening, yeast and water, eggs and vanilla and beat until dough is smooth. Let stand while preparing filling.

- Mix filling ingredients in a medium saucepan. Bring to a boil, then lower heat and simmer uncovered for 5 minutes, stirring occasionally, until mixture thickens. Remove from heat and let cool.

- On a well-floured surface, roll out dough to 1/8 - inch thickness. Add flour whenever dough threatens to stick. Cut dough into pieces 5 inches square. Place 1 tbsp. of filling in center of square, then fold dough over on top and pinch to close. Pinch ends closed. Cover buns with a towel and let stand 30 minutes.

- Preheat oven to 375°F. Brush buns with egg wash and sprinkle tops with sugar. Bake until browned, about 16 minutes. Serve warm or at room temperature.

-----------------

Many thanks to family, friends, and blueberry bun connoisseurs who shared their thoughts and memories with me — especially to Ann and Harry Moran (my aunt and uncle), and to Mr. Kip Kaplansky.