Articles

Love Your Neighbour:

Evaluating the Creative Impulse of Armand Lemiez

Abstract

This paper proposes an alternative perspective for evaluating the work of a community artist, Armand Lemiez. Evaluative categories often reflect the ethnocentric criteria of collectors representing both private and public interests, not the community in which the work was made. Classification is a cultural expression of the receiver's response to an object's aesthetic, it is not an inherent component of any object. Value, therefore, is an expression of a social aesthetic. Public and private representatives have evaluated the work of Armand Lemiez based on elite criteria derived from public expectations, governmental policy, and personal background. Community members, the folk, have their own criteria that are distinct, but no less relevant than those of elite interests. This paper is intended as an overview and introduction to the work of Armand Lemiez. The terms elite and folk are used in their most general sense in order to facilitate discussion.

Résumé

Cet article propose une perspective différente à l'évaluation de l'œuvre d'un artiste communautaire, Armand Lemiez. Les catégories d'évaluation reflètent souvent les critères ethnocentriques des collectionneurs qui représentent à la fois des intérêts publics et privés mais pas ceux de la collectivité dont l'œuvre est issue. La classification est une expression culturelle de la réponse d'une personne à l'esthétique d'une œuvre, elle n'est pas une composante inhérente d'un objet. Des représentants des secteurs publics et privés ont évalué l'œuvre d'Armand Lemiez en se basant sur des critères d'élite dérivant des attentes du secteur public, des politiques gouvernementales et de leur évolution personnelle. Les membres de la collectivité ont leurs propres critères distincts, mais tout aussi pertinents que ceux de l'élite. Dans cet article qui se veut un aperçu et une introduction à l'œuvre d'Armand Lemiez, l'auteur emploie les termes elite (élite) et folk (gens de la collectivité) dans leur sens le plus général afin de faciliter la discussion.

The Social Aesthetic

1 Value is an inescapable component of human existence. It is the basis on which those attributes intended to facilitate the perpetuation of a cultural system are preserved and transmitted. Objects, once made and therefore removed from the context of the creative process, acquire a social context that instigates a process of categorization. The maker of the object is the first judge of its value. Every subsequent individual to come in contact with the object will apply subjective criteria for determining the success, therefore the value, of the work. For individuals, such as Armand Lemiez, who are not interested in selling their work and motivated instead by a desire to commemorate their community's past, a good indicator of the work's value may be the response of the community. Value and the determination thereof is, therefore, considered to be an expression of a social aesthetic.

2 Gerald Pocius states that "all people engage in a wide range of creative acts that are judged by standards of excellence."1 Excellence, or value, is a determining criteria of what we call art. Art, in turn, is an expression of skilful behaviour. Pocius defines art as "the manifestation of a skill that involves the creation of a qualitative experience (often categorized as aesthetic) through the manipulation of forms that are public categories recognized by a particular group."2 The determination of what is art is the product of a social aesthetic. Philip Bohlman applies the idea of a social aesthetic to the presentation of musical canons, what he describes as "those repertories and forms of musical behaviour constantly shaped by a community to express its cultural particularity and the characteristics that distinguish it as a social entity."3 Folk music canons form "as a result of the cultural choices of a community or group. These choices communicate the group's aesthetic decisions,"4 which are themselves a result of "a community's transformation of cultural values into aesthetic expression."5 According to Bohlman there are an unlimited number of aesthetic expressions in any given society at any given time. Canons, or expressions of a specific group's aesthetic, emerge for reasons relevant to the needs of the group.

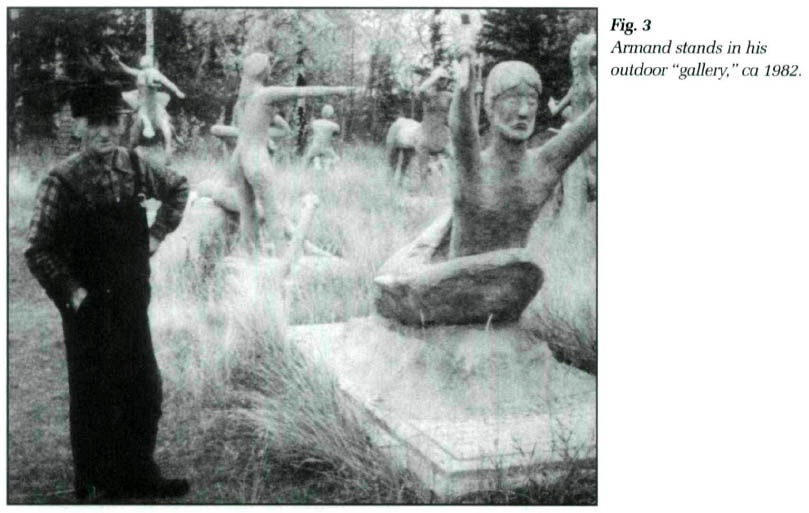

3 Both Pocius and Bohlman place the emphasis of determining value on the group in which the object is to function. Value does not determine whether or not something is adopted by a community, rather it is adoption by a community that gives an object value. Rather than trying to create a category into which the object of study is intended to fit, Pocius and Bohlman are suggesting that we more readily "recognize the things that others consider as art"6 and the rationale behind their decisions. The following discussion explores the relationship between two competing social aesthetics, generally speaking they represent the elite aesthetic and the folk aesthetic, and questions whether or not we have accorded equal consideration to the perspective of the latter.

The Naturalization of Armand Lemiez

4 Armand Lemiez was born in Belgium in 1894. His own account of his childhood is as follows, taken from a letter he wrote to the editor of the Manitouwapa Times.

5 The family emigrated to Canada in 1911, and, after a year in Winnipeg purchased land just south of Grahamdale, in the Interlake Region of Manitoba.

6 The early twentieth century was a period of increased immigration and settlement in the Canadian west. The federal government's National Policy, introduced in 1879, prompted an international program to attract European immigrants to settle the land that had been recently acquired by the Canadian government. Lemiez, therefore, at the age of seventeen, was part of an influx of immigrants from continental Europe, a large portion of which were peasant farmers who came with the dream of owning their own land. In Manitoba, many Belgian immigrants became mixed farmers and developed small industries in dairy cattle, horse breeding, and market gardening.8

7 By 1910, most of the prime agricultural properties in the southern portion of the province had been purchased; those that were still available were commanding a high price. Many of the new immigrants, therefore, being poor, purchased cheaper land to the north in the Interlake. Jack Giles characterized the region as

8 Not only was the Interlake Region undesirable, in 1911 it was also largely inaccessible. The northern railway had only recently been built and offered little more than a series of sidings surrounded by wilderness.

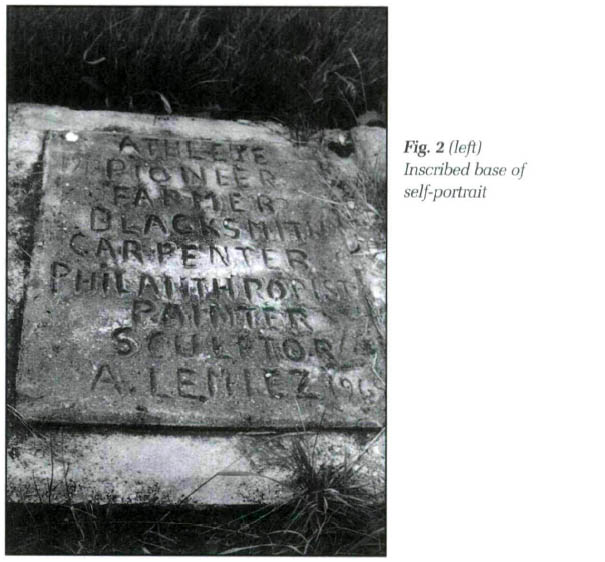

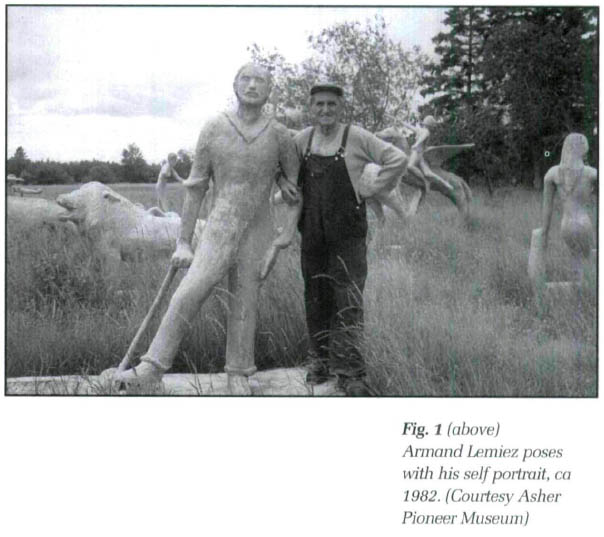

9 Little is known about the details of Lemiez's life. He owned 160 acres of land, which he purchased in 1911 for $10 as part of a government land grant. He was never married and lived with his mother on the homestead until she died in the 1950s. After her death, Lemiez continued to farm and lived alone. By all accounts, he was a successful fanner, following in the mixed farming tradition of the Belgian immigrant. He kept a large portion of his land under cultivation, kept horses to work his land, developed a series of experimental fish ponds for raising trout, maintained a fruit orchard, and raised cattle. He painted throughout his life and at the age of seventy-two embarked on a decade of intense creative activity that resulted in a collection of concrete sculptures that have become his legacy. In 1969 he "tried to make my portrait in sculpture. At that time I still had my moustache...and I got the axe, I was a pioneer then. And the whole country was a pioneer"11 (Fig. 1). He inscribed the following description of himself into the platform base: "A athlete, and a pioneer, 1912 and then blacksmith, farmer, blacksmith, carpenter, philanthropist — I helped forty-one families around here — painter, sculptor. A. Lemiez and a little bit of preacher — Love your Neighbour"12 (Fig. 2).

The Creative Endeavour

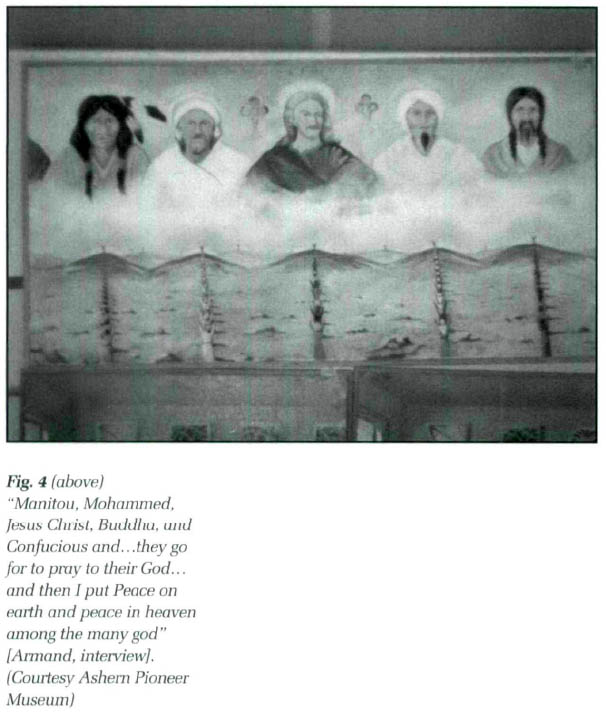

10 Starting in Canada's centennial year, and continuing over the next nine years (his last statue is dated 1976), Lemiez produced twenty-one life-size concrete sculptures depicting mythological, religious, and political scenes (Fig. 3). He produced approximately two statues a year with the highest production occurring in 1969 when he produced four, and the lowest being in 1970, 1973, and 1976 during each of which he only produced a single statue. He was also a prolific painter producing his own interpretations of images from various printed sources as well as fantastical, often politically oriented, pictures from his own imagination (Fig. 4). In his own words, "many, many paintings are from photo. But some aren't. Nothing. Take this girl here. No photo. Nothing. Just I tried to make a naked girl coming in the sky and she got four leaf clover and flower forget-me-not. Good luck and forget-me-not."13 It is believed that he had several hundred paintings on his property at the time of his death but these became the property of his inheritors and have disappeared since the estate was settled.14

11 Lemiez was concerned with maintaining the integrity of his site. In an interview he said, "I got the sculpture here I got the building there. I don't want to move the paintings to Moosehorn or other place...they should stay here because the sculptures are here they cannot be moved."15 The whole property comprises a literal and aesthetic dialectic between the sculptures, the physical landscape, and the man. To fully grasp the importance of this dialogue, one must understand that the objects that Lemiez has produced — the paintings, sculptures, buildings, physical alterations of the landscape — are all extensions of the man. Everything in Lemiez's world is alive. Not only do his objects elicit reminiscences of his past,16 they are also very much alive in his present as a tool for engaging audiences in a moral, political, and philosophical discussion as wide-ranging and autodidactic as Lemiez himself. The anthropomorphic transcendence between Lemiez and his objects is most evident in his relationship with the sculptures. Not only do they embody a vast body of personal associations and experience, they are also considered as entities in their own right; as living beings.17 Visitors were formally introduced to his sculptures: "Now I want to introduce you to my grandfather, the monkey" or "Next. She's a mermaid, say hello to that girl, there" and "I'm going to introduce you to my wife. But I am a bad boy. She stay out every night...I should bring a blanket one winter night to keep her warm."18

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1 Display large image of Figure 4

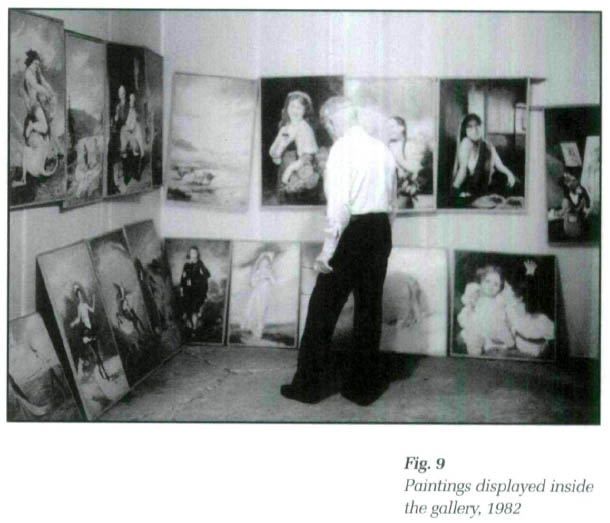

Display large image of Figure 412 Narrative and dialogue are key components to the experience of the objects. Each object contains a narrative component that is either a direct allusion or is inscribed as descriptive text accompanying the sculpture. Overlapping narratives between objects creates a dialogue and when these dialogues involve elements of the physical environment the entire landscape comes to life. A visitor to the site is, therefore, not simply seeing a collection of paintings or sculptures, rather a visitor is being immersed in the many interwoven facets of Lemiez's life.

The Sculptures

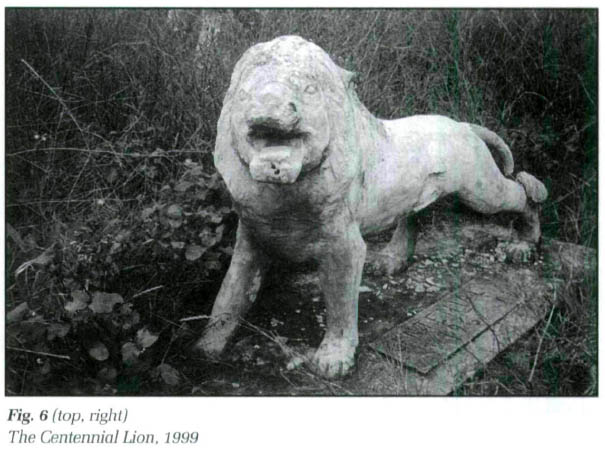

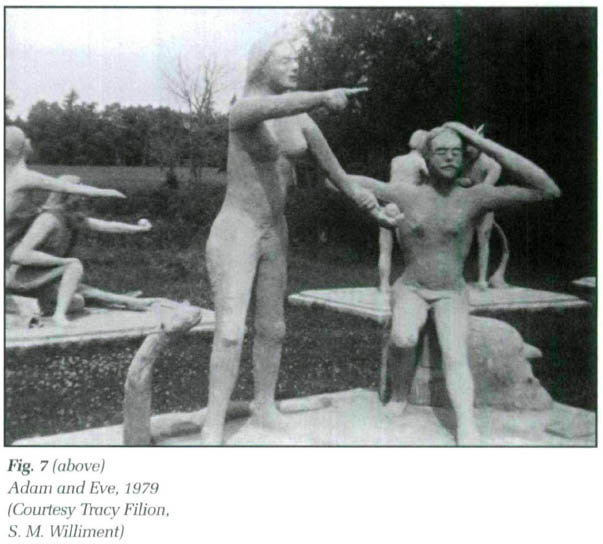

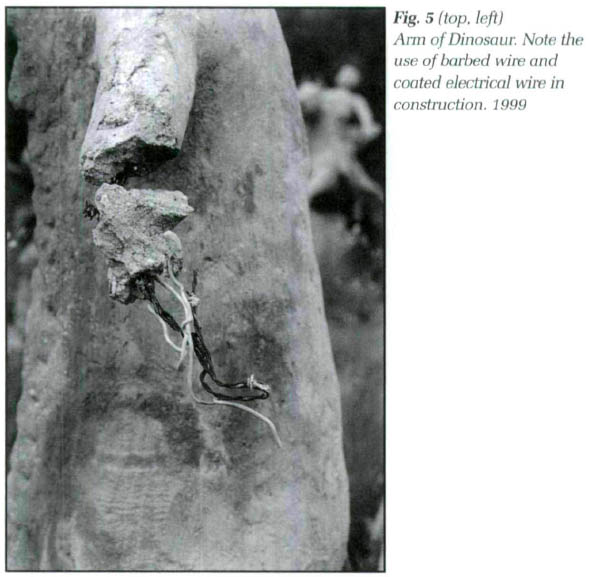

13 The sculptures are all life size. They are made of concrete hand moulded onto a rough metal frame constructed from scraps of metal (Fig. 5). They are not painted although in some instances the surfaces have been textured. Natural materials are incorporated as finishing touches. The deer's and the devil's horns are made of deer antler and, to make teeth for a dinosaur, Lemiez "went along the highway and picked some flat teeth [stones].19 "All of the sculptures are constructed on a flat rectangular base into which the date of construction is inscribed. In many, primarily the ones made later, text is also inscribed into the base. The initial use of text consisted of the single words "Centennial" and "Centenaire" on two sculptures: an English lion and a French deer respectively, made to commemorate the Canadian centennial in 1967 (Fig. 6). He used text again on two sculptures in 1969, one of which was his self portrait discussed earlier. By the 1970s the text had become much more descriptive and integral to the sculpture's compounding narrative. One of three sculptures dealing with Adam and Eve (dated 1971), has God pronouncing: "I have a big nose to track yoo down and a big mouth to give you HEHL! Be honest" (Fig. 7). In the sculpture referred to as Rosema (dated 1972) the text reads: "Welcome to my place I get along very good with my husband Armand I never quarrel with him. But he leave me out in the cold. Rosema forgive me."

14 Several sculptures are also designed to incorporate elements of the surrounding landscape into their narrative; for example, the Adam and Eve mentioned earlier. Lemiez states, "Here, is ah, Adam and Eve and Eve is showing where she got the fruit in my orchard."20" Another piece represents two large ape-like creatures, one male and one female, sitting together on a small bench. She has her arm around him while he is "playing the mandolin for his girlfriend and singing too."22 Both figures are romantically oriented toward the setting sun. A life-size centaur, out "to look for anything to fight,"22 is facing south and has his right arm raised to shield his eyes. In daylight. this gesture literally blocks the sun.

15 Two groups of two sculptures are also made to interact with each other: the lion and the deer (dated 1967), and the bather and the mermaid (dated 1968). The lion and deer, as mentioned earlier, were constructed to commemorate the Centennial. According to Lemiez, "it's a, the British lion. You see lots of [antagonism] between the French and English I put Centennial in English, 1967. That's the lion running after the friend jumper [white-tailed deer]. Over there I put Centennial in French."23 The second pairing includes "a young lady taking a bath and she is surprised to see a mermaid saying hello to her" and a mermaid figure, "geology of the past, very nice girl and she say hello to that girl taking a bath."24

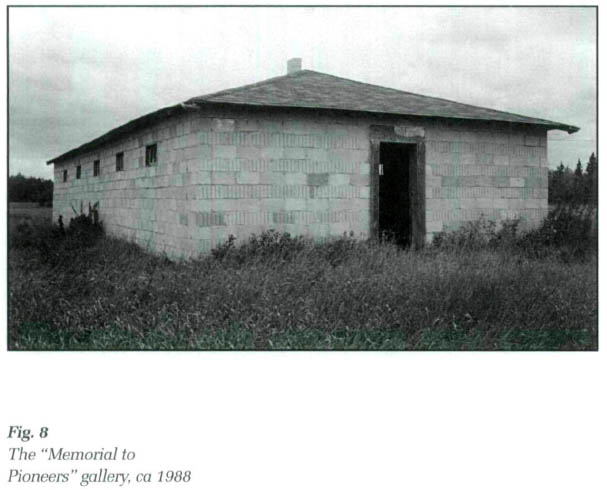

The Buildings and Yard

16 The primary architectural elements of the yard are the original farm house, the "Memorial to Pioneers" gallery, and the second house. The sculptures are all located in a series of parallel rows to the north and west, behind the second house. The gallery (Fig. 8) and the second house are constructed of concrete blocks and are located so as to border the sculptures, organized in a series of rows, on two sides. This compressed living space is typical of a farmstead where the intention is to maximize the amount of land under cultivation and to organize the various buildings so as to provide protection from the weather. It may also be a consequence of his advanced age and limited mobility when he began constructing the sculptures.

17 The original farmhouse was constructed of wood with successive additions made to the original structure over time. The two modern buildings, the gallery and the second house, were both made from concrete blocks. His motivations for using concrete as a construction material are not known. Pragmatically, it was most likely an economical building material. The gallery may have been the first, of the two, buildings that he made. It was built as a "Memorial to Pioneers" to permanently display his paintings. According to Lemiez, a local museum "want me to give some paintings to put in the museum and the museum is just a building...made with lumber, but they, like I say, my painting have to go in a building that's why I built it. This house too. Nobody ever built a house like this. Because the wall is ten inch thick."25

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 518 The two concrete buildings parallel Lemiez's developing aesthetic that would find its most elaborate expression in the sculptures. His shift from the original wooden farmhouse to the concrete home appears to have had a temporal correlation with his artistic development from a painter to a sculptor. It is possible that the move between houses represents an attempt to separate the old from the new, the hard times from the good, the past from the future, or more fundamentally, the farmer from the artist. Refocusing his property so that it revolved around his gallery of statues and is bound by the cinder houses may have been important for Lemiez as a means of identifying himself as an artist. Physically, it meant that his experiential world was now dominated by the medium of concrete rather than of wood. His world also became something over which he had a degree of control. The concrete buildings were bounded, solidly demarcated spaces as opposed to the sprawling series of additions made to the original homestead.

19 If we look at the relationship between buildings in the farmyard from a spatial perspective there appears to be two separate thematic loci of activity defined by the earlier life as a farmer and the later life as an artist. Rather than the sprawling farmyard that took shape over time due to necessity and circumstance, exemplified in the series of additions to the original home, the later impulse to create lead to the intentional construction of a compressed living space defined by the two cinder block buildings on two sides, the cultivated field on the third side, and scrub bush on the fourth. Although a more detailed analysis is required, it is likely that Lemiez's impulse toward a less cluttered aesthetic is expressed in the austere design of the cinder block buildings. It is also present in the unpainted concrete used to construct the buildings as well as the sculptures.

20 Changes in spatial relationships may also be viewed as indicators of Lemiez's artistic development. Too little is known about the patterns in his work. How long had he considered sculpting in concrete before making his first sculpture? Did he sculpt or carve in other materials? Did he stop painting once he began his work as a sculptor? Is there a symbiotic relationship between the subjects of the paintings and the statues? What is the relationship between the two media? I would like to suggest that the statues are Lemiez's most idiosyncratic expression. They are certainly his most complex. While he explored his creativity in the more formal medium of painting, often reproducing the work of the Great Masters, his most personal and ethereal creativity is in the concrete sculptures. These sculptures were created in an extended burst of creative activity, which lasted for the last ten years of his life. The importance of the relationship between this creative endeavour and Lemiez's developing self-identity as an artist is, to some degree, supported by an analysis of his changing relationship with space in the farmyard, as evidenced in die construction of new buildings and the inclusion of the physical landscape in the narratives accompanying his multi-dimensional art pieces.

The Paintings

21 The most prolific component of Lemiez's artistic output were his paintings. Unfortunately, very little is known about them. A concerted effort needs to be made with local residents to see what still exists in the community. Numbers vary as to how many paintings Lemiez had produced. Andrew Blicq, a reporter with the Winnipeg Free Press, remembers touring the gallery with Lemiez,

22 The subject matter for his paintings was eclectic. Blicq has described them as, "varied and sometimes bizarre and humorous reflections of his interest in politics, religion and social justice."27 They were "hung or painted right on the walls of the wood and concrete buildings, are of political and historical figures, historical scenes, portraits of his family and friends, landscapes and the rugged life of the area's homesteaders and settlers."28 Cecil Semchyshyn, at the time the Provincial Director of Cultural Affairs, remembered visiting Lemiez's "Memorial to Pioneers" art gallery:

23 Most of the printed discussion surrounding Lemiez's work focuses on the paintings. While this may be a reflection of the more accessible medium of painting as opposed to the sculptures, it is also a component of the social aesthetic. The subjects of Lemiez's paintings are representative of a more familiar artistic tradition and are, therefore, more readily described and qualified than the more eclectic sculptures (Fig. 9). While a visitor to the site may have an overpowering emotional response to the sculptures, he or she would lack the confidence and language to discuss their feelings. They would, therefore, find a more appropriate outlet in the paintings, many of which depicted subjects with which a viewer would be familiar, familiarity derived from tradition being an important element in the development of the social aesthetic.30

24 In 1980, when he was eighty-five years old, Lemiez became an adamant promoter of his art. Nearing the close of his life, he was concerned for the preservation of his creations. He made several requests for support from the provincial government. In 1980, the director of the Provincial Historic Resources Branch, Cecil Semchyshyn, visited the site to assess the cultural significance of the artifacts. Semchyshyn was directly involved in making the decision regarding the cultural significance, or value, of Lemiez's artwork for the Province of Manitoba.31 Semchyshyn was a representative of the Province's social aesthetic. In his informal assessment of the paintings, quoted previously, Semchyshyn showed an "elite." or educated perspective of art. He commented on Lemiez's "improvements on the masters,"32 noting The Last Supper and the Mono Lisa. From his perspective as a minister of cultural affairs, he stressed that the "most intriguing paintings were his historical paintings and landscapes of rural Manitoba.33 These were the works considered of highest value to a government body chosen to document the province's cultural mosaic and vanishing past.

25 Andrew Blicq evaluated the work from a perspective familiar with contemporary cultural trends. Unlike Semchyshyn, Blicq's interest was not bound by government policy. Similar to Semchyshyn, though, Blicq realized that preservation of the site was dependent upon recognition of its value in terms of a larger social aesthetic. Blicq, therefore, also turned to the paintings as a medium readily communicated and appreciated by his readers. Images of the sculptures were used because they were visually evocative. In his assessment of the paintings, Blicq could not avoid making his own value judgement. He states, "His talent was quite unfocused and some of the stuff was junk. It was...stuff he copied from magazines and things he tried. It wasn't, in my unprofessional opinion, that good or that interesting but about ten percent of these five hundred paintings were pure magic."34 He acknowledges the greater social value in Lemiez's work when he describes a "picture of horses hauling a plow or a dredge on the farm and it just struck me in a moment how important that painting was. That he had captured something that was passing now out of our lives."35 We might consider the contemporary interest in the paintings of Cree artist Allen Sapp in light of Blicq's response to Lemiez's folklife images. In his role as a reporter, Blicq walks a fine line between being a representative of public opinion and a shaper of public opinion. While he acknowledges the faults in Lemiez's work, he also stresses the recognizable values, thereby asserting the value of the larger body of work, and consequently shaping public opinion in favour of the paintings.

26 Both Blicq and Semchyshyn have professional criteria for determining the value of Lemiez's work, criteria external to the artist's creative impulse. These criteria allow them to extract a single component of the work — images representing a rural lifestyle — and present that as characteristic of the whole; which it isn't. This ethnocentric process of selection and validation is indicative of the perspective by which "elite" institutions have perceived of "folk" products. Value has been determined without due consideration of the importance of the work for the community in which the work has been created. This idea is presented as an observation, not necessarily a criticism.

27 Freida Clark, Lemiez's god-daughter, provides a "folk" perspective:

28 For her, some of the paintings were "larger ones some were smaller ones and so on. But the ones that stand out the most in my mind were the ones he painted of people." Clark also appreciates the realism, to her eye, of the paintings. She states "they were just perfect. You never saw anything done as well as they were." Her concern is not with images depicting the vanished past or the landscapes of rural Manitoba, instead, it is with what is familiar and of personal interest. Unlike Blicq and Semchyshyn, Clark's appreciation is derived from an unlettered sense of value — realism and familiarity. Neither does she discount any of the paintings, rather she stresses the favourable aspects of the work she is most affected by, thereby respecting the eclecticism of Lemiez's oeuvre in light of her own aesthetic criteria with regard to his body of work.

The Creative Impulse

29 At the age of eighty Lemiez began a one-man campaign to solicit support from the provincial government to help preserve his work, "however, Lemiez said his attempts to obtain help from the provincial department of tourism have not been successful."37 In his own words, Lemiez felt, "this is worth preserving...people come from across [Lake Manitoba] to see the works."38 He had become a public figure.

30 Advocating pleasure was one of the motivating factors for his creative endeavours. The line of text he chose to inscribe in his self-portrait is simply "Love your neighbour" which, according to Lemiez is "the best religion." In one sculpture, God is shaking hands with the Devil and the two of them are agreeing to "work for peace on earth from now on. Mankind forgive us." An article in the Stonewall Spectator stated that "those who remember him say he loved to have people see his artwork, although he refused to sell any of it."39 It then quotes a Grahamdale resident who remembered that "He loved to talk. He just loved it when people would come by and he'd talk and talk and talk."40 The parish priest remembered that

31 Cecil Semychsyn recalled that he

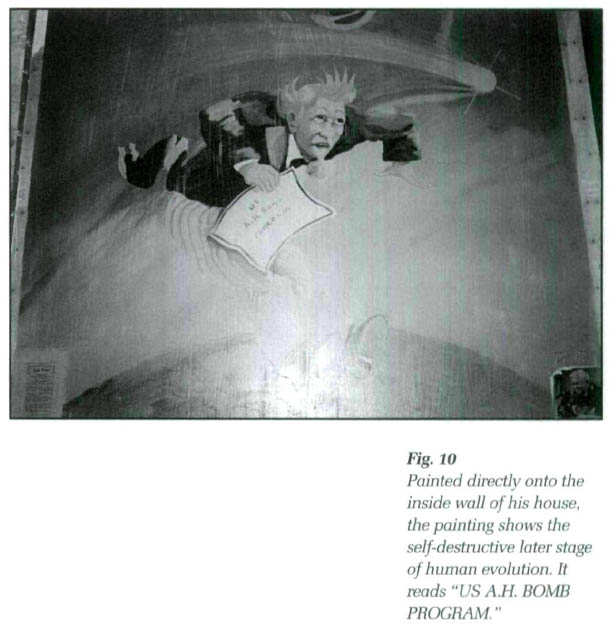

32 He also expressed anger about the U.S. involvement in Vietnam in an "emotional series of paintings depicting the war and role of then-president Richard Nixon."43

33 By the end of his life, Armand had achieved a great deal of popularity. He and his creations had become a local tourist attraction and an outing for local school children. Blicq states that "he relished the fact that school groups and tourists would travel to his farm to see his work."44 According to Lemiez, visitors numbered in the thousands: "something I want to tell you now. When 1000,2000 people come...you know they have to walk there and [I] explain for maybe six to eight hours [a day] all summer...I got the visitor book. I filled twenty-two, twenty-three page."45 The paintings and sculptures were appendages through which Lemiez communicated his deepest beliefs and concerns to the public. His artwork was intended as a gift to the world. The philanthropic motivation for his creative endeavours is what prompted him to approach the provincial government late in his life in an attempt to preserve the gallery that he had created. In an interview he stated, "I have nobody, no son, no family to take it over...I don't know what will happen to them when I am gone. I cannot live for two hundred years."46

34 We have an unfortunate inclination to conceive of the eccentric folk artist as a loner and a social outcast. While this may be the case in certain circumstances, it is not necessarily the norm. Armand Lemiez, although contentious, was not an outcast, and the work he produced was not only an expression of his sense of community, it has also proven to be of enduring value to the community. Since his death in 1984, community members have continued, unsuccessfully, his campaign to have the site preserved.

Display large image of Figure 10

Display large image of Figure 1035 A 1979 issue of artscanada included statements by and interviews with a selection of Canadian folk artists. It is interesting to see how their creative development parallels Lemiez's. Most of the artists are retired and most began making things late in life. Eva Dennis, a painter, states that she had very little time to paint while she worked as a teacher. Harvey Innes, also a painter, began drawing after he sold his farm. Nova Scotia folk artist Collins Eisenhauser stated that he began carving when he was sixty-five — "when they figure you're not fit for work anymore."47 French Canadian folk artist Edmond Châtigny describes his beginnings as a folk artist:

36 In most of these artists there is a desire to express the goodness of the world, to use their objects to make people happy. Donaldson notes a "genuineness" in Eisenhauser's carvings, "a rejection of all he sees as 'rotten' in today's world...his joy is in the making, in the creation.49 While the work may seem simple it is not naive. Eisenhauser's Adam and Eve images "reflect the innocence he once felt in the world, but equally what he knows the world can be."50 When asked about his concern that art dealers are selling his works for much more money than they pay him, Eisenhauser responds, "I don't want it. If I could make somebody happy that's worth a lot to me."51 Philanthropy and the passing on of knowledge are common themes among these artists. Molly Lenhardt, a painter, states that "Art-talented people take pride in bringing back memories, in re-creating scenes of the past, the present or future...Artists are historians in many ways, putting on record and reliving good or bad, all is beautiful when expressed in art."52 Fred Moulding makes objects and scenes reminiscent of his days as a farmer. He began carving because he "thought that the younger people of today did not know what we used in the early days."53

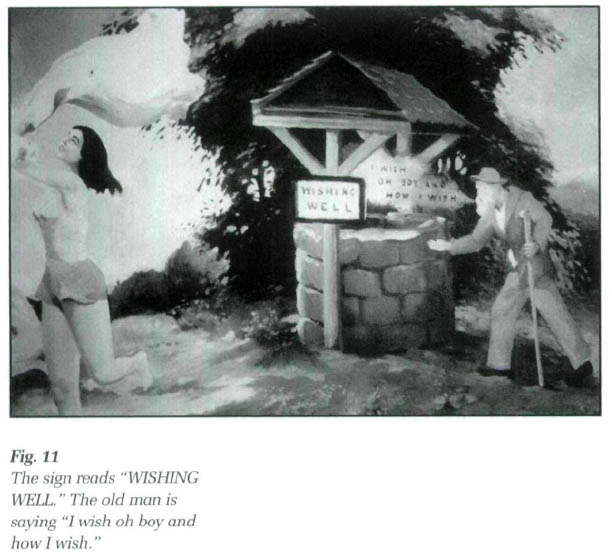

Display large image of Figure 11

Display large image of Figure 1137 Blicq states that Lemiez's interest in painting was renewed around 1920 by a hired hand who had studied art in Germany. According to Lemiez "in the winter time I started to paint with him."54 He began the sculptures in 1967, when he was seventy-three, and made the last one in 1976, when he was eighty-two years old. Although he had painted during most of his life, the intensive work of making the sculptures did not begin until after he had retired and become less active on the farm. Part of the reason for the restructuring of his yard may have been to create a smaller, more manageable working space for an aging man.

38 It is important to consider Lemiez's motivations from an elementary perspective such as his niece used to view his work: "you know. Some were larger ones some were smaller ones and so on."55 It must be experienced emotionally, not viscerally. The emphasis is not upon an understanding, or an evaluating of the work like Blicq and Semchyshyn were inclined to do as representatives of their respective social aesthetics, rather it is upon an experiential reaction like one might have to abstract art. The source of the strength and immediacy of the work is that it grew out of a practical way of life. Like many of the other artists just quoted, Lemiez's artwork was a way of filling out a busy day and later became a means of rounding out a life full of contemplation and experience. The objects he made represent significant and considered expressions of his thoughts and feelings (Fig. 11). They are also a means of passing the time when one gets old and is no longer able to work. As he says, "When you reach sixty you keep on working. If you've got nothing to do, take a walk. Have some work to do."56 Lemiez's creative legacy was in part his personal make-work project.

39 To return to the question of value, Armand Lemiez brought the same integrity to the making of his artwork that he needed to make a life for himself as a pioneer in the Interlake. The primary value of the work was in knowing the job was well done. In a sense he is evoking the essence of the pioneer spirit when he says that his goal in life, as expressed in his art, has been "to find the truth in life. You have to have something which your reason tells you is right."57 The many strangers Armand Lemiez had visit him, from school children and teachers, to reporters and politicians, is a clear indication of the value of the man and his vision. That people still visit, almost twenty years after his death, with the site greatly deteriorated and vandalized, the paintings gone and many sculptures fallen to rubble, is a clear indication of the enduring value of his work.58